How Sustainability Reports Align to Sustainable Development Goals: Insights From Naples' Waste Management Company

Funding: This work was supported by European Commission - Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe - Fondo Sociale Europeo (European Social Fund).

ABSTRACT

Sustainability reporting is crucial to follow up companies' alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through increased transparency to identify companies' impacts. However, the large flexibility and lack of clear quantitative targets hamper the integration of sustainability reporting with the SDGs, reducing sustainability declarations to appendices of traditional financial reports. We examined the sustainability reports from 2010 to 2020 of ASIA s.p.a, a public utility company in Naples, as a case study. We evaluate the quantitative and qualitative social-ecological information related to the SDGs. Later, national SDG targets were downscaled to the company level in order to assess the company's degree of alignment or divergence. The results indicate that an overemphasis on economic data, compared to socio-environmental aspects, risks compromising the effectiveness of their disclosure. Additionally, the absence of quantitative targets for reducing negative impacts minimizes the potential of these reports as strategic tools for corporate organization.

1 Introduction

In response to intensifying environmental and social challenges, sustainability reporting (SR) has gained prominence as a mechanism for companies to communicate their corporate responsibility initiatives and contribute to global sustainability goals (Bebbington and Unerman 2020). This rise is accompanied by growing national and international regulatory frameworks, as well as increasing societal expectations that corporations have to contribute to sustainable development (Di Vaio et al. 2022; Adams 2017). Central to this expectation is corporate social responsibility (CSR), which has evolved to encourage businesses to consider not only their financial outcomes but also their long-term social and environmental impacts (Lepore and Pisano 2022). In this context, SR, whether voluntary or mandated, has become a critical mechanism for reducing information asymmetries, enhancing governance, and supporting informed decision-making by stakeholders and investors (Blowfield and Frynas 2005; Bushman and Smith 2001). Since the establishment of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) a decade ago, SR has acquired a new dimension as a relevant strategy to progress towards the achievement of the SDGs. Specifically, Target 6 of SDG 12 calls on companies to adopt sustainable practices and integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycles. Consequently, the alignment between corporate sustainability disclosures and the SDGs has become a key focus for scholars, practitioners, and international organizations (Lepore and Pisano 2022). Several scholars and organizations have proposed frameworks and methodologies to address the disconnection between SR and SDG reporting. The global reporting initiative (GRI), for instance, offers a set of guidelines that encourage companies to incorporate SDG-related indicators into their sustainability reports (GRI 2022). The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) has also developed tools to help businesses align their CSR strategies with the SDGs, providing a roadmap for integrating sustainability targets into corporate decision-making processes (WBCSD 2023). These initiatives aim to standardize reporting practices and improve the quality of information disclosed by companies, thus enhancing transparency and accountability.

However, despite these efforts, significant gaps remain in the alignment between SR and the SDGs, particularly regarding the measurement of progress toward specific SDG targets. Most existing studies focus on policy recommendations, conceptual linkages, or qualitative assessments, with limited empirical evidence on how firms concretely align their enterprise-level sustainability indicators with SDG global targets (Malay 2021). Moreover, current approaches typically lack context-specific methodologies for measuring this alignment at the firm level, making it difficult to assess how companies are contributing to specific SDG outcomes in practice (Tsalis et al. 2020). Without consensus on indicator selection, firms risk cherry-picking SDGs or targets where they perform better or that are easier to report, undermining the robustness and credibility of their sustainability assessments (Gebara et al. 2024; Hák et al. 2016; Heras-Saizarbitoria et al. 2022). From here, a clear necessity emerges to systematically evaluate the alignment between companies SR and the SDGs targets.

This paper addresses this critical gap by applying a novel downscaling model that enables the systematic evaluation of how corporate sustainability indicators align with the SDGs. Using sustainability reports from 2010 to 2020 of ASIA s.p.a, a public utility company, as a case study, this research offers an empirical analysis of the extent to which the company's reports correspond to specific SDG targets. In doing so, the study pursues two central research questions: (1) to what extent do the sustainability reports of ASIA s.p.a effectively align with the SDGs? and (2) what are the main gaps or challenges in this alignment, and how do these affect the company's social, environmental, and economic performance? Our results indicate an increasing alignment between ASIA s.p.a SR and SDG targets. Yet, there is a clear imbalance favoring economic outcomes over socio-environmental aspects. Additionally, the lack of quantitative targets to reduce negative impacts minimizes the potential of these reports as strategic tools to materialize sustainability improvements.

To answer such questions, we first describe institutional theory as the theoretical ground of our analysis (Section 2) and the legislative framework surrounding CSR and SR and their linkage with SDGs (Section 3). In Section 4 we outline the data collection process and provide background information on ASIA s.p.a as a case study and it presents the methodology employed in this study, including a detailed description of the downscaling model used to evaluate the firm's indicators. We present the limitations of our analysis in Section 5, and, in Section 6, we describe the main findings of our study. In Section 7, we discuss the main implications of both our methodological approach and findings. Finally, Section 8 summarizes the main findings of this study.

2 Background

Over time, scholars have used different theories to explain environmental disclosure ranging from stakeholder and legitimacy, institutional, agency, and signaling theories (Lepore and Pisano 2022). Early frameworks focused on the ethical responsibilities of corporations, beginning with Bowen (1953), who emphasized duties beyond profit-making. This led to the rise of stakeholder theory, formalized by Freeman (1984), which argued that companies must respond to the needs of all stakeholders, employees, communities, and governments, to ensure long-term success. In this light, CSR is seen as a strategic approach that aligns corporate actions with the broader social and environmental needs of these diverse groups (Alipour et al. 2019; Huang and Kung 2010; Deegan 2002; Ullmann 1985; Mitchell et al. 1997). Concurrently, agency theory (Jensen and Meckling 1976) framed disclosure as a tool to reduce information asymmetries between managers and shareholders. From this perspective, disclosures serve to mitigate potential conflicts (Barako et al. 2006). The 1980s and 1990s saw increased attention to environmental crises, prompting the development of legitimacy theory (Suchman 1995), which interpreted sustainability disclosures as efforts to maintain public approval. This social contract compels firms to operate in ways that reflect societal expectations, with non-compliance creating a “legitimacy gap” that may hinder resource access or marketability (Lindblom 1993; Tilling and Tilt 2010; Lu and Abeysekera 2014). Through these disclosures, companies aim to enhance their visibility, reinforce reputation, and gain stakeholder support (Cormier et al. 2004).

However, CSR disclosures are not always indicative of substantive CSR commitments; rather, companies may engage in symbolic legitimacy, using CSR information as a means of impression management to meet external expectations without making genuine operational changes (Chelli et al. 2018). Legitimacy theory therefore distinguishes between strategic legitimacy, aimed at achieving or restoring legitimacy, and institutional legitimacy, which emphasizes maintaining legitimacy by adhering to established norms and standards (Chelli et al. 2014). Emerging in this context, institutional theory (DiMaggio and Powell 1983) gained traction by explaining how companies adopt similar behaviors within specific regulatory and cultural environments, driven by institutional pressures that encourage conformity, a process known as isomorphism (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). As global sustainability frameworks like the GRI and UN Global Compact became dominant, institutional theory proved useful in explaining the global diffusion of SR practices. This framework is especially relevant following the 2015 adoption of the SDGs and the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive (Directive 95/2014/EU). While the SDGs provide a global roadmap, companies often engage in selective isomorphism, focusing on SDGs that align with their existing operations (Perello-Marin et al. 2022). Empirical studies across the energy and utilities sectors consistently highlight a gap between SDG rhetoric and implementation. Arena et al. (2023) found that oil and gas firms selectively report SDG contributions to enhance reputation rather than drive change. Buniamin et al. (2021) observed that Malaysian companies prioritize energy-related SDGs aligned with business interests over broader sustainability goals. In the utilities sector, D'Amore et al. (2024) reported fragmented SDG strategies, while Giacomini et al. (2025) noted that stakeholder engagement remains largely superficial. Leopizzi et al. (2023) revealed that electric utilities often reference SDGs without integrating them into performance frameworks. Similarly, Makarenko et al. (2023) showed that transparency claims around SDG 7 often lack accountability. Manes-Rossi and Nicolò (2022) concluded that SDG language is frequently symbolic, lacking substantive commitment.

Furthermore, while the SDGs provide a critical framework for guiding global sustainability efforts, they have also faced significant criticism. One key critique centers on the emphasis on economic growth as a central tenet of development, particularly in SDG 8, which promotes “sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth.” While this goal aligns with the aim of improving global living standards, separating economic growth from environmental degradation (Parrique et al. 2019). Critics argue that pursuing SDG 8 in its current form risks perpetuating an economic system that extracts, consumes, and disposes of resources at an unsustainable rate, thereby undermining broader SDG objectives such as climate action, life on land and water, and the reduction of inequality (Hickel 2019). Scholars have raised concerns about the SDGs' implicit assumption that economic growth is a prerequisite for human development (Esquivel 2016). As Hickel (2019) pointed out, “the document does not specify whether it is an end in itself, or a means to an end.” Szirmai (2015) suggested that the assumed link between growth and human development is employment in Target 8.5 impling that growth should create more jobs. However, empirical evidence radically challenges the feasibility of absolute decoupling. Parrique et al. (2019) highlight key barriers, including rebound effects, resource depletion, and insufficient technological advancements, which undermine the possibility of sustaining growth without exacerbating environmental pressures. Moreover, problem shifting occurs when solutions to one ecological issue create new challenges, such as increased resource extraction for green technologies like electric vehicles (Parrique et al. 2019). Recycling limitations, the structural dependence of services on material consumption, and cost shifting to lower-income nations further complicate the green growth narrative (Parrique et al. 2019). In their assessment of the SDGs, the International Council for Science and the International Social Science Council (2015) highlight that the goals lack a strong theoretical foundation and exhibit inherent contradictions between development and sustainability objectives, though they do not elaborate on the specifics of these contradictions. For instance, targets such as 8.4 aim to decouple growth from environmental degradation, yet they lack clear thresholds for material footprint reduction (Dittrich et al. 2012; Hoekstra and Wiedmann 2014; Bringezu 2015). Based on this theoretical aspect, this study employ an evaluation of SDGs in decoupling terms showing the difference of considering economic growth separated from environmental impacts.

3 Legislative Framework

To enhance corporate SR, the European Union introduced Directive 2003/51/EC, which mandated environmental information disclosure for companies. This requirement was further extended by Directive 2014/95/EU (Non-Financial Reporting Directive) to cover large public-interest entities, including listed companies, banks, and insurance firms, with over 500 employees. This directive aimed to improve transparency and accountability by requiring these companies to disclose information on environmental, social, employee-related, human rights, anti-corruption, and bribery matters. Despite these efforts, issues with the comparability and reliability of SR persisted due to the lack of standardized reporting formats and detailed guidelines. To address these challenges, the European Commission proposed the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) in April 2021. The CSRD aims to expand the scope of reporting obligations to more companies, including smaller and medium-sized enterprises, thereby enhancing the overall quality and consistency of sustainability information. To achieve these objectives, the European Commission tasked the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) with developing comprehensive and standardized SR standards. These standards are designed to ensure that SR are consistent, comparable, and aligned with the EU's sustainability goals and the SDGs. The new directive is expected to significantly improve corporate transparency, enabling investors and stakeholders to make more informed decisions based on reliable and comparable sustainability data.

4 Data and Methods

4.1 Data

Data were sourced from ASIA s.p.a's annual reports and supplemented with additional information obtained directly from the company. ASIA s.p.a is a public utility company in Naples responsible for waste management. Established in 1991 through the merger of several smaller entities, ASIA s.p.a manages waste collection, transportation, and disposal for Naples and its surroundings, serving over 1 million residents. Additionally, the company oversees street cleaning services and maintains public parks and gardens. Naples has faced two significant waste management crises in 1994 and 2008, highlighting profound democratic challenges (D'Alisa et al. 2010), affected by the criminal phenomenon of illegal waste dumping, famously known as the “land of fires” (terra dei fuochi). These events have significantly shaped the company's structure and evolution. The launch of recycling initiatives dates back to 2001, while door-to-door waste collection started in 2008 during the peak of the waste crisis. The first sustainability report from ASIA s.p.a was published in 2010, incorporating data that dates back to 2008, and it has consistently reported their yearly data since then. The introduction of the SDGs in 2015 marks the midpoint of the study period. Therefore, it is particularly intriguing to assess how the publication of SR before and the introduction of SDGs thereafter have influenced the company's reporting processes, as well as its socio-environmental and economic performances. ASIA s.p.a has historically used the GRI methodology for reporting. However, due to evolving standards and varying accountability practices, the data collected for this study exhibit heterogeneity and occasional incompleteness. To enhance data reliability, cross-fertilization techniques were applied where applicable.

4.2 Methodology

Specifically, this study (i) has reviewed the economic, environmental, and social indicators reported by ASIA to determine the representative index, in terms of percentage of GRI used in comparison of all available, as suggested by Tsalis et al. (2020); (ii) it has applied a downscaling model based on the GRI (2022), WBCSD (2023), and “Alleanza Italiana per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile” ASviS (2021; 2022; and 2023) framework to assess the precision of the company's sustainability performance relative to global benchmarks; and (iii) has examined the evolution of ASIA's indicators over time to understand how the company has adapted its sustainability strategies in response to emerging global sustainability challenges.

4.2.1 Representativity Index

The first part of the study examines the construction of ASIA s.p.a's SR. Following the methodology proposed by Tsalis et al. (2020), we analyze the indicators used and assess their representativeness in proportion to the maximum of available indicators as provided by GRI (2022). This analysis highlights priority objectives and identifies areas that may remain overlooked. To this end, we extracted GRI standards from ASIA's reports and, then, we linked these disclosure themes to the 17 SDGs using the classification provided by GRI (2022). The GRI (2022) publication named “Linking the SDGs and the GRI Standards” offers a framework that enable corporations to use GRI standards to refers to each goal. The GRI criteria includes 77 standards that can be linked to 305 topics present in the SDGs, highlighting how many themes assess a company's reporting across multiple SDGs. Each SDG is evaluated using 18 standards on average, though this number greatly varies by goal (Table 1). For example, 49 indicators can be used to refer to SDG 8, while only 2 is used to assess SDG 2, underscoring the varying significance and relevance of each goal to business operations.

| Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | Global reporting initiative (GRI) | N° |

|---|---|---|

| 1—No poverty | 207-1, 207-2, 207-3, 207-4, 202-1, 203-2, 413-2-a | 12 |

| 2—Zero hunger | 411-1, 413-2-a | 2 |

| 3—Good health and well-being | 401-2-a, 403-6-b, 403-10, 403-9-a, 403-9-b, 403-9-c, 403-6-a, 203-2, 305-1, 305-2, 305-3, 305-6-a, 305-7, 306-1, 306-2-a, 306-2-b, 306-2-c, 306-3-a, 306-3-b, 306-3-c, 306-4-a, 306-4-b, 306-4-c, 306-4-d, 306-5-a, 306-5-b, 306-5-c, 306-5-d | 35 |

| 4—Quality education | 404-1-a | 3 |

| 5—Gender equality | 202-1, 401-1, 404-1-a, 401-3, 404-3-a, 405-1, 405-2-a, 406-1, 408-1-a, 409-1-a, 414-1-a, 414-2, 203-1, 401-2, 2-9-c, 2-10 | 18 |

| 6—Clean water and sanitation | 303-1-a, 303-1-c, 303-2-a, 303-4, 306-1, 306-2-a, 306-2-b, 306-2-c, 303-3-c, 303-5-a, 303-5-b, 304-1-a, 304-2, 304-3-a, 304-3-b, 304-4-a, 306-3-a, 306-3-b, 306-3-c, 306-5-a | 27 |

| 7—Affordable and clean energy | 302-1, 302-2, 302-2-a, 302-3-a, 302-4-a, 302-5-a | 7 |

| 8—Decent work and economic growth | 201-1, 404-2, 203-2, 204-1-a, 301-1-a, 301-3, 302-1, 302-2-a, 302-3-a, 302-4-a, 302-5-a, 306-2-a, 2-7-a, 2-7-b, 2-8-a, 202-1, 202-2-a, 401-1, 401-2-a, 401-3, 404-1-a, 404-2, 404-3-a, 405-1, 405-2-b, 408-1, 409-1-b, 2-30, 403-1-a, 403-1-b, 403-2-a, 403-2-b, 403-2-c, 403-2-d, 403-4-a, 403-4-b, 403-5-a, 403-7-a, 403-8, 403-9, 403-10, 406-1, 407-1, 414-1-a, 414-2 | 49 |

| 9—Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | 201-1, 203-1 | 5 |

| 10—Reduced inequalities | 2-7-a, 2-7-b, 401-1, 404-1-a, 404-3-a, 405-2-a, 207-1, 207-2, 207-3, 207-4 | 10 |

| 11—Sustainable cities and communities | 203-1, 306-1, 306-2-a, 306-2-b, 206-2-c, 306-3-a, 306-4-a, 306-4-b, 306-4-c, 306-4-d, 306-5-a, 306-5-b, 306-5-c, 306-5-d | 14 |

| 12—Responsible consumption and production | 301-1-a, 301-2-a, 301-3-a, 302-1, 302-2-a, 302-3-a, 302-4-a, 302-5-a, 303-1-a, 303-1-c, 305-1, 305-2, 305-3, 305-6-a, 305-7, 306-1, 306-2-a, 306-2-b, 206-2-c, 306-3-a, 306-3-b, 306-3-c, 306-4-a, 306-4-b, 306-4-c, 306-4-d, 306-5-a, 306-5-b, 417-1 | 45 |

| 13—Climate action | 201-2-a, 302-1, 302-2-a, 302-3-a, 302-4-a, 302-5-a, 305-1, 305-2, 305-3, 305-4-a, 305-5-a | 11 |

| 14—Life below water | 304-1-a, 304-2, 304-3-a, 304-3-b, 304-4-a, 305-1, 305-2, 305-3, 305-4-a, 305-5-a, 305-7 | 11 |

| 15—Life on land | 304-1-a, 304-2, 304-3, 304-4-a, 306-3-a, 306-3-b, 306-3-c, 306-5-a, 305-1, 305-2, 305-3, 305-4-a, 305-5-a, 305-7 | 18 |

| 16—Peace, justice, and strong institutions | 403-9-a, 403-9-b, 403-9-c, 403-10, 410-1, 414-1-a, 414-2, 408-1, 2-23-a, 2-23-b, 2-26, 206-1, 307-1-a, 416-2, 417-2, 417-3, 418-1, 419-1-a, 205-1, 205-2, 205-3, 415-1-a, 2-11, 2-15, 2-12, 2-9-c, 2-10, 403-4-a, 403-4-b, 418-1 | 30 |

| 17—Partnership for the goals | 207-1, 207-2, 207-3, 207-4 | 8 |

| Total | 305 |

- Note: This table illustrates the alignment between the GRI standards and specific SDG targets, detailing which standards can be used to report on each target and the total number of relevant standards per goal (GRI, 2022).

-

Rj = Iaj/Ijmax.

here j ranges from 1 to 17, indicating the corresponding SDG.

4.2.2 Performance's Index

Secondly, the study assesses ASIA s.p.a's progress towards achieving SDGs' targets by benchmarking its performance against internally set quantified targets. To do so, national objectives were scaled down to the company level (Table 2). Most business goals are set using the original SDGs and the works of the ASviS (2021;2022; and 2023). The remaining goals, where quantitative targets are not set, have been built based on previous research and studies (see Supporting Information S1 for full description). The environmental and social performance of the company in relation to various SDGs was assessed using multiple indicators. As aforementioned, a single indicator can relate to multiple SDG targets; thus, specific indicators were selected based on the quantitative targets described. For instance, while greenhouse gas emissions are linked to SDGs 3, 12, 13, 14, and 15 according to the GRI (2022), this research focused on using the emissions indicator solely to evaluate SDG 13, which pertains specifically to emissions. Thus, it was not employed to assess SDG 3, despite its relevance to human health. Instead, emissions were combined with other indicators to measure progress towards specific goals, such as corporate decoupling in relation to SDG 8.

| SDGs | National level indicators | Business Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1—No poverty | 1.2.1 Proportion of population living below the national poverty line, by sex and age | (1) Increase in the gap between average income and relative poverty by 16% |

| 1.2.2 Proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions | (2) Increase in the gap between average income and relative poverty by role and gender by 16% | |

| 1.4.1 Proportion of population living in households with access to basic services | ||

| 2—Zero hunger | 2.4.1 By 2030, reduce by 20% the use of fertilizers distributed in non-organic agriculture compared to 2020. | (1) Increase the proportion of composting of urban organic waste to 20%. |

| 3—Good health and well-being | 3.8.1 Coverage of essential health services | (1) Reduce the rate of workplace injuries by 25% |

| 3.9.3 Mortality rate attributed to unintentional poisoning | (2) Reduce the rate of occupational diseases by 25% | |

|

3.9.1 Mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution 3.9.2 Mortality rate attributed to unsafe water, unsafe sanitation and lack of hygiene (exposure to unsafe Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for All (WASH) services) |

(3) Reduce the number of environmental incidents by 25% | |

| 4—Quality education | 4.3.1 Participation rate of youth and adults in formal and non-formal education and training in the previous 12 months, by sex | (1) Increase in training hours by 20% |

| 4.5.1 Parity indices (female/male, rural/urban, bottom/top wealth quintile and others such as disability status, indigenous peoples and conflict-affected, as data become available) for all education indicators on this list that can be disaggregated | ||

| 5—Gender equality | 5.1.1 Whether or not legal frameworks are in place to promote, enforce and monitor equality and non discrimination on the basis of sex | (1) Elimination of the gender pay gap (equal pay for similar roles) |

| 5.4.1 Proportion of time spent on unpaid domestic and care work, by sex, age and location | (2) Appointment of a female board member by 2030 | |

| 5.5.1 Proportion of seats held by women in (a) national parliaments and (b) local governments | (3) Achieve gender parity (50% women employed) by 2030 | |

| 5.5.2 Proportion of women in managerial positions | ||

| 6—Clean water and sanitation | 6.3.1 Proportion of domestic and industrial wastewater flows safely treated | (1) Reduce water consumption by 25% |

| 6.3.2 Proportion of bodies of water with good ambient water quality | ||

| 7—Affordable and clean energy | 7.2.1 Renewable energy share in the total final energy consumption | (1) Reduce final energy consumption by 20% |

| 7.3.1 Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP | ||

| 8—Decent work and economic growth | 8.1.1 Annual growth rate of real GDP per capita | (1) Increase absolute decoupling by 20%: energy consumption |

| 8.2.1 Annual growth rate of real GDP per employed person | (2) Increase absolute decoupling by 20%: water consumption | |

| 8.4.1 Material footprint, material footprint per capita, and material footprint per GDP | (3) Increase absolute decoupling by 20%: waste production | |

| 8.4.2 Domestic material consumption, domestic material consumption per capita, and domestic material consumption per GDP | (4) Increase absolute decoupling by 20%: greenhouse gas emissions | |

| 9—Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | 9.5.1 Research and development expenditure as a proportion of GDP | (1) Investments in R&D for 3% |

| 10—Reduced inequalities | 10.4.1 Labor share of GDP | (1) Increase local suppliers by 20% |

| 10.4.2 Redistributive impact of fiscal policy | (2) Reduce the wage gap between administrators and workers by 15% | |

| (3) Increase distributed added value to the community by 25% | ||

| 11—Sustainable cities and communities | 11.6.1 Proportion of municipal solid waste collected and managed in controlled facilities out of total municipal waste generated, by cities | (1) Increase the recycling rate to 60% |

| 12—Responsible consumption and production | 12.5.1 By 2030, achieve a 60% recycling rate for urban waste. | (1) Reduce the quantity of waste produced by 15% |

|

12.6 Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle |

(2) Adopt a sustainability reporting | |

| (3) Adopt a methodology to assess environmental impact | ||

| 13—Climate action |

13.2.2 Total greenhouse gas emissions per year |

(1) Decrease greenhouse gas emissions by 55% |

|

13.2.1 Number of countries with nationally determined contributions, long-term strategies, national adaptation plans and adaptation communications, as reported to the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

(2) Adoption of a mitigation and adaptation plan | |

| 14—Life below water | 14.3.1 Average marine acidity (pH) measured at agreed suite of representative sampling stations | (1) Decrease plastic consumption by 15% |

| 15—Life on land | 15.2.1 Progress towards sustainable forest management | (1) Decrease land consumption by 10% |

| 16—Peace, justice, and strong institutions | 16.5.1 Proportion of persons who had at least one contact with a public official and who paid a bribe to a public official, or were asked for a bribe by those public officials, during the previous 12 months | (1) Increase the number of unionized personnel by 15% |

| 16.5.2 Proportion of businesses that had at least one contact with a public official and that paid a bribe to a public official, or were asked for a bribe by those public officials during the previous 12 months | (2) Reduce lawsuits against the company by 20% | |

| 16.7.1 Proportions of positions in national and local institutions, including (a) the legislatures; (b) the public service; and (c) the judiciary, compared to national distributions, by sex, age, persons with disabilities and population groups | ||

| 17—Partnership for the goals | 17.2 By 2030, achieve the 0.7% share of Gross National Income (GNI) allocated to Official Development Assistance (ODA). | (1) By 2030, allocate 0.7% of revenues to international cooperation and sustainable development projects |

Finally, the evolution of the company's initiatives is calculated over the 12 years of available data (2008–2020), determining the alignment or deviation from SDG objectives. This assessment serves to empirically evaluate the extent to which the targets set by companies in the SR match real actions towards improving their sustainability performance, rather than merely remaining as an act of transparency.

-

w_SDGx1 = w_SDGx2 = … = w_SDGxi = w

In this context, SDGx represents one of the SDGs, thus x ranges from 1 to 17, while w_SDGxi denotes the weight of specific targets within each SDG. It is therefore possible to evaluate the trend of performance as:

-

SDGxi = (SDGxi t1 − SDGxi t0)/SDGxi t0 × 100

In the formula above, SDGxi t0 represents the initial available data point chronologically for the specific item under consideration, while the subscript t1 indicates that it pertains to the year 2020. In this way, it is possible to calculate the percentage degree of alignment or divergence of each specific target by considering:

-

d_SDGxi = (SDGxi/SDGxi*) × 100

here SDGxi* denotes the target of a specific goal, whereas d_SDGxi indicates the percentage degree of alignment or deviation from that target.

If d_SDGxi is > 0, it means that the company is moving in the right direction, while if it is < 0, data show that performance does not align with the SDG goal considered.

- D_SDGx = w * i = 1 to n d_SDGxi

We will refer to it as “general score.”

5 Limits

During the research process, we have encountered several limitations that should be noted. As previously mentioned, a primary limitation when analyzing sustainability reports is the heterogeneity of indicators used to measure corporate performance compared to those employed as targets for the SDGs. Specifically, the possibility of using a single indicator to contribute to the achievement of multiple SDGs weakens the connection between the GRI standards and the metrics established as targets. Furthermore, the significant flexibility granted by legislation in the preparation of SR makes these indicators difficult to compare. While it can be argued that the use of GRI standards can be compared statistically, as demonstrated through the representativity index, the task of aligning these standards with the target objectives presents a more complex challenge. These aspects warrant greater attention from both legislators and researchers, particularly in identifying parameters that allow for robust and effective comparisons.

Moreover, the presence of outlier data due to the COVID-19 pandemic further complicated the assessment. To mitigate this issue, data most affected by the pandemic—such as waste production—were carefully managed, and discrepancies across years were addressed in the corresponding sections. Notably, throughout most of the pandemic period, ASIA s.p.a was classified as an essential sector and operated in accordance with safety protocols, as reported in the 2020 Sustainability Report. As a result, the core functionality of the organization remained largely unaffected. This study, therefore, focuses on assessing the impacts of this operational continuity. Finally, SDGs 2 (Zero Hunger) and 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) are not included in this study. The former relates to land consumption, while the latter concerns international partnerships. Although the down-scaled model proposed specific targets for these SDGs, the assessment faced two key challenges. First, the company did not evaluate these goals using specific GRI indicators. Even when attempting an independent assessment, it became evident—as previously discussed—that the company had not allocated investments in these areas, making it impossible to evaluate these indicators. Second, assessing land consumption would require a specialized methodology for measuring land coverage over the years, which falls beyond the scope of this research.

6 Results

6.1 ASIA s.p.a Reporting Results

The company has consistently employed the primary accounting system GRI, just like 73% of the companies analyzed in the 2018 SDGs Reporting Challenge at the international level (PwC 2018). Before the change in standards that took place in 2016, the distinction between indicators was based on the following categories: (i) strategy and analysis; (ii) report parameters, governance, commitments, stakeholder engagement; (iii) environmental performance; (iv) economic performance; (v) social performance; (vi) human rights; and (vii) product responsibility. From the first publication of SR in 2010 to the last using this method in 2015, ASIA s.p.a consistently used all indicators for the first three categories, while gradually increasing the number of indicators for environmental and social performance each year. Specifically, environmental indicators increased from 1 in 2010 to 8 in 2015, while social indicators grew from 9 to 13. Economic indicators saw the most significant increase, rising from 2 to 30 over the 5 years considered. Finally, indicators on human rights and product responsibility were introduced only in 2011, reaching their peak at 11 and 17, respectively, in the final year (see Supporting Information S2 for more information). Following the publication of the 2030 Agenda and the corresponding SDGs, GRI updated its standards, providing more tools for aligning reporting with these goals. The first sustainability report reflecting this change was in 2017, where the initial three categories were consolidated into two sections called: (i) general disclosures and (ii) management approach. Simultaneously, the categories related to economic, environmental, and social performance remained as materiality aspects. From this perspective, the first categories included 56 indicators in the first 2 years and 58 in the last two, with the only increase due to the addition of general disclosures. On the other hand, performance indicators increased from 9 to 31, and it is on these that we will focus on the following analysis.

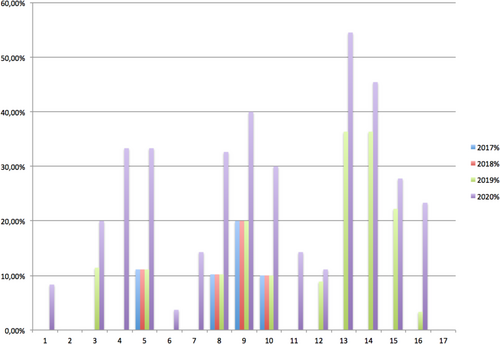

Figure 1 shows the number of targets that can be linked to the indicators used in the SR. As mentioned earlier, an indicator can refer to one or more targets, which explains why 31 indicators covered as many as 68 over 305 targets in 2020 (Supporting Information for more details). From our analysis, there is a consistent increase in the use of GRI standards and the corresponding representation of SDG. Specifically, the GRI standards used have increased from 9 in 2016 to 68 in 2020, representing 9 and 40 SDG targets, respectively. As a result, the SDGs included in the reports have expanded from 4 to nearly all 15, with the only exceptions being SDGs 2 and 17 in 2020. Looking at this year, we found that the majority of the SDGs were addressed to some extent. In fact, 15 out of the 17 SDGs, accounting for 88%, were covered in the company's report. However, out of the total 169 SDGs targets, only 40 were covered in the company's report. Moreover, there is an unequal distribution of coverage across the various targets. Economic targets exhibited a higher degree of exposure compared to environmental or social targets, with only three (14.3, 15.2, and 3.9) out of the top ten mentioned targets pertaining to environmental issues and all referring to emissions. This can also be observed in the SR prior to 2020, where Goal 8 accounts for 5 out of 9 of the cited objectives. The specific targets and their respective references in the 2020's report are detailed below (Tables 3 and 4):

| SDGs | Frequency | SDGs—Target | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8—Decent work and economic growth | 21 | 8.8—Protect labor rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment | 6 |

| 3—Good health and well-being | 10 | 5.1—End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere | 5 |

| 5—Gender equality | 8 | 8.5—By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value | 5 |

| 16—Peace, justice, and strong institutions | 7 | 14.3—Minimize and address the impacts of ocean acidification, including through enhanced scientific cooperation at all levels | 5 |

| 12—Responsible consumption and production | 6 | 15.2—By 2020, promote the implementation of sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation, restore degraded forests and substantially increase afforestation and reforestation globally | 5 |

| 13—Climate action | 6 | 3.9—By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination | 4 |

| 9—Industry, innovation, and infrastructure | 5 | 12.4—By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment | 4 |

| 14—Life below water | 5 | 8.2—Achieve higher levels of economic productivity through diversification, technological upgrading and innovation, including through a focus on high-value added and labor-intensive sectors | 3 |

| 15—Life on land | 5 | 10.3—Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard | 3 |

| 4—Quality education | 3 | 16.5—Substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms | 3 |

| SDGs | Target | Degree | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | x% | x% | 132.20% (score) |

| 1.1 | 16% | 30% | 189% (mean) |

| 1.2 | 16% | 17% | 106% (men) |

| 1.2 | 16% | 12% | 75% (women) |

| 2 | 20% | 27.5% | 137.50% |

| 3 | −25% | −22.69% | 77.90% |

| 4 | 20% | 31% | 154.76% |

| 5 | x% | x% | −17.29% |

| 5.1 | −100% | −35% | 35% (−31% if managers are excluded) |

| 5.2 | 50% | 6% | 13% |

| 5.3 | 1 | 0 | −100% |

| 6 | −25% | 25% | −99.57% |

| 7 | −20% | 20% | −102.35% |

| 8 | X% | X% | −69.39% |

| 8.1 | 20% | −33% | −163% |

| 8.2 | 15% | 10% | 66% |

| 8.3 | 25% | 21% | 83% |

| 8.4 | 30% | −22% | −75% |

| 9 | 2.50% | 1.23% | 41.08% |

| 10 | X% | X% | 95.55% |

| 10.1 | 20% | 34% | 170% |

| 10.2 | −15% | 1% | −5% |

| 10.3 | 25% | 51% | 122% |

| 11 | −25% | −13% | 56.67% |

| 12 | X% | X% | −35.40% |

| 12.1 | −15% | 16% | −106% |

| 12.2 | 1 | 1 | 100% |

| 12.3 | 1 | 0 | −100% |

| 13 | X% | X% | −85.38% |

| 13.1 | −55% | 39% | −71% |

| 13.2 | 1 | 0 | −100% |

| 14 | −15% | 32% | −214.73% |

| 15 | X% | X% | X% |

| 16 | X% | X% | −23.64% |

| 16.1 | 15% | 2% | 14% |

| 16.2 | −20% | 12% | −61% |

| 17 | 0.7% | 0% | 0% |

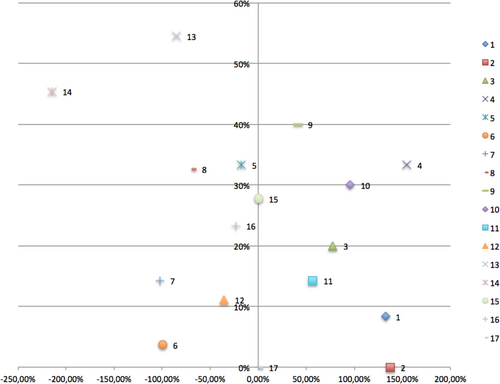

- Note: The Degree column represents the achieved percentage relative to the target, while the Score column quantifies performance based on the average results. For SDGs 1, 5, 8, 10, 12, 13, and 16 we presented both the overall score of the goal and the score of each subtarget. Figure 2 summarizes the findings of this study by visually combining the Representativity Index and Performance Scores for each SDG. As can be observed, the data points are distributed almost evenly across the four quadrants of the graph, providing a clear representation of the relationship between the two variables.

6.2 Performances Results

The first finding from our performance analysis is that there is no correlation between the representativeness of indicators in sustainability reports (SRs) and corporate performance within the sector. Whether evaluated in terms of the absolute incidence of goals or the relative incidence of indicators used, an increased usage of indicators did not correlate with enhanced performance (further details can be found in the Supporting Information S3 outlines the calculations for each index, while table 24 of Supporting Information S4 presents the linear model used for correlation). However, for ASIA s.p.a, the publication of SRs has come together with performance improvements, driven by socio-economic factors. Notably, significant advancements were observed in poverty reduction and zero hunger (SDG 1 and 2), the reduction of workplace accidents and inequalities (SDG 3 and 10), and the increase of training hours and R&D investments (SDG 4 and 9). The only notable environmental performance improvement was in the percentage of waste collected by the company (SDG 11). On the other hand, despite economic growth, the company has increased its environmental impact in terms of material, energy, and water consumption (SDG 6, 7, 12, 14), as well as emissions and waste production (SDG 12, 13), as briefly outlined in the evaluation of SDG 8. In particular, the lack of a climate mitigation plan (SDG 13) and the absence of a governance structure more attentive to gender composition (SDG 5) seem to negatively affect the company's socio-environmental performance. Lastly, the rise in complaints against the company, along with a lack of investment in social partnerships, results in a negative score for SDG 16 and a score of 0 for SDG 15.

6.2.1 Target Reached

6.2.1.1 SDG 1—No Poverty

From 2008 to 2020, the company exceeded its target by increasing the gap by an average of 30%, representing a 189% achievement of the target. Looking at this time range, all roles surpassed the target, almost doubling it. However, focusing on the period from 2011 to 2020, after the second waste crisis and when it became possible to disaggregate data by gender, the situation changed significantly. We observe an average increase of only 6%, which is 40% of the target, where executives and managers maintained substantial growth (39% and 17%, respectively), while employees and workers saw their gap increase by only 8% and 6%, respectively. Looking deeper into gender-specific data, it becomes evident that this increase was primarily driven by the rise in male executives (39%, with no female executives ever recorded) and the sole female manager (+25%). On the other hand, female workers and employees experienced a smaller increase, with a rise of just 4% and 8%, respectively. Aggregating these figures using the previously explained methodology, we can still affirm that the company achieved a score of 96% of the target. However, as noted, this growth was largely driven by male managerial roles and the sole female manager.

6.2.1.2 SDG 2—Zero Hunger

Regarding the second development goal on eliminating hunger, we considered the percentage of organic waste disposed of through composting, which, as stated by the Agenda 2030, represents a way to maintain soil fertility and improve the sustainability of the agri-food supply chain. For this reason, the target was set at 20% of the organic fraction collected. During the period considered, the company ASIA more than doubled this portion, increasing from 11% in 2011 to 27.5% in 2020, thus exceeding the target. However, it is important to note that this metric does not account for the fact that the waste treatment facilities are not owned by the company, and most of the waste requires transportation outside the region, and in some cases, even outside the country. This, in turn, exacerbates the environmental impact of transportation.

6.2.1.3 SDG 4—Quality Education

The down-scaling model posits to increase training hours by 20%. Since 2008, ASIA has increased training hours by an average of 31%, broken down as follows: executives 75%, employees −57%, and workers 74%. This achievement represents 155% of the target.

6.2.2 Goal's Aligned but Not Reached

6.2.2.1 SDG 3—Good Health and Well-Being

The corporate objective aims for a 25% reduction in the injury rate. To evaluate this, we analyzed metrics including work-related injuries, the injury frequency index, days absent due to injuries, the injury severity index, and the average duration of injuries (in days). Our findings indicate that ASIA has achieved a 22.69% reduction in the injury rate since 2008, reaching 78% of the target.

6.2.2.2 SDG 9—Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

The objective is to invest in R&D 3% of total investments. From 2017 onwards, ASIA invested an average of 1.48%, reaching only 1.23% in 2020, which represents 41% of the target.

6.2.2.3 SDG 10—Reduced Inequalities

This objective has three sub-targets: local supplier engagement, reducing the remuneration gap between roles, and increasing community value distribution. Local suppliers from Naples decreased by 15%, while those from other provinces in Campania doubled (+110%), and other Italian suppliers increased by 7%. Overall, this surpasses the 20% target. Concerning the remuneration gap, while managers' salaries showed a slight decrease (−1%) compared to executives, the gap increased for employees and workers by 1% and 2%, respectively. Thus, the company is moving in the opposite direction concerning the target of a 15% reduction in the pay gap, resulting in a −5% deviation. However, the added value distributed to the community increased by 51% from 2008 to 2019, doubling the 25% target. Weighing these three sub-targets indicates the company has quite reached goal number 10 with a general score of 96%, despite significant internal disparities highlighting areas for improvement.

6.2.2.4 SDG 11—Sustainable Cities and Communities

The target is to increase the recycling rate to 60%. As of 2020, the recycling rate stands at 34%, which is 57% of the set target.

6.2.3 Misalignment to Target

6.2.3.1 SDG 5—Gender Equality

The target for the company is a 50% female workforce and the elimination of the gender pay gap. Notably, there has never been a female member on the Board of Directors, affecting both objectives. The average percentage of female staff from 2008 to 2020 was 3.3%, broken down by category (excluding executives): managers 11.8%, employees 13.8%, and workers 1.7%. Women consistently earned less than men, with pay gaps of −0.94% for managers, −10.61% for employees, and −14.50% for workers. The only improvement noted was in 2020 when the female manager earned 3.62% more than her male colleagues, compared to −5.29% in 2011. Overall, the company stands at 35% of the goal for closing the gender pay gap, but this figure falls to −31% when excluding managers. Considering also the lack of appointment of an executive, this results in an overall score of −17% compared to the general target.

6.2.3.2 SDG 8—Decent Work and Economic Growth

Economic growth alone exceeded the declared target, reaching 27% compared to the 20% goal. However, as emphasized in the scientific background, growth in itself does not necessarily indicate sustainable development, as it may still rely on unsustainable resource consumption (Hickel 2019; Parrique et al. 2019). To address this, a decoupling approach was applied, assessing environmental resource consumption relative to net revenues. Decoupling measures focus on key indicators, including electricity (kWh), LPG (liters), natural gas (cubic meters), water (cubic meters), total waste produced (tons), and CO2 equivalent emissions. In this context, a decrease in the decoupling index signifies higher environmental consumption relative to economic growth, whereas an increase suggests improved resource efficiency. The analysis showed: decreases in electricity (−37%), LPG (−24%), natural gas (−37%), and emissions (−22%), while waste production (+21%) and water consumption increased (+10%). Notably, 2020's data were skewed by the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in anomalous figures. Including 2020, the decoupling index shows a more than threefold increase (+216%); excluding that year, the increase drops to just 21%. Overall, with decoupling targets of 20% for energy, 15% for water, 25% for waste, and 30% for emissions, the company achieves 65% of its target only when including 2020. Excluding the anomalous data, the achievement index falls to −69%, indicating a close correlation between company growth and natural resource consumption.

6.2.3.3 SDG 12—Responsible Production and Consumption

The objective is to reduce waste production by 15%. Considering the anomaly of 2020, waste production decreased by 57%. However, limiting the analysis to 2019 reveals a 16% increase in waste, resulting in a complete deviation from the target. Considering the adoption of sustainability reports as an achievement of a goal on one hand, but the absence of a methodology for managing environmental impact, this allows for a generalization of a deviation (−35%) from the overall target due to the impact that waste production has on the overall result.

6.2.3.4 SDG 13—Climate Action

The goal is to reduce emissions by more than half (−55%). However, compared to 2011, the company has seen a 39% increase in emissions, resulting in a 71% misalignment with this objective. Considering the non-adoption of the mitigation plan, the result increases in a general score of −85%.

6.2.3.5 SDG 16—Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

The aim is to increase the unionized workforce by 15% and reduce complaints against the company by 20%. The company achieved a unionized workforce of 79% in 2020, a 2% increase since 2008, aligning with 14% of the target. However, complaints against the company increased by 12%, leading to a 61% misalignment with the target. Overall, the company is 24% misaligned with objective number 16.

6.2.4 Completely Divergence

6.2.4.1 SDG 6—Clean Water and Sanitation

The target is to reduce water consumption by 25% compared to 2008 levels. However, during the evaluation period, water usage rose from 61,615 cubic meters to 76,953 cubic meters, marking a 25% increase and a complete deviation from the target (−100%).

6.2.4.2 SDG 7—Affordable and Clean Energy

We focused solely on energy consumption, which included electricity (kWh), LPG (liters), and natural gas (cubic meters). Notably, natural gas consumption decreased by 30%, surpassing the target reduction of 20%. However, electricity and LPG consumption increased by 59% and 33%, respectively. Overall, energy consumption rose by 20%, contrary to the targeted 20% reduction. For this reason, the general score is assessed as −102%.

6.2.4.3 SDG 14—Life Below Water

The target is to reduce plastic consumption by 15%. Analyzing plastic collection in the city, it has increased by 32% from 2010 to 2020, representing a 215% misalignment with the target.

6.2.5 Unmeasurable Goal

6.2.5.1 SDG 15—Life on Land

Unfortunately, data are unavailable due to insufficient historical coverage information on the buildings owned by the company.

6.2.5.2 SDG 17—Partnership for the Goals

Regarding Goal 17, the 2030 Agenda calls for achieving a 0.7% share of Gross National Income (GNI) allocated to Official Development Assistance (ODA) by 2030. We adapted this target by setting a goal to allocate 0.7% of company revenues to international cooperation and sustainable development projects. Unfortunately, the company has never invested in these projects, resulting in a 0% achievement of this specific target.

7 Discussion and Implications for Corporate Sustainability Reports

The publication of sustainability reports has increased the amount of public information provided by ASIA s.p.a, thereby increasing the awareness of its social, economic, and environmental impacts by the public, sectoral stakeholders, and the company itself. The substantial increase in the indicators used over the period under consideration reflects the company's growing alignment with global objectives and societal demands (Lepore and Pisano 2022). However, has the increasing publicly available information materialized in improved economic, social and environmental performance? We observed that, as raised in previous studies (Bebbington and Unerman 2020; Unerman et al. 2018; Di Vaio et al. 2022), the reporting process itself influences the outcomes. This influence commonly takes place as an overlap of economic data as an inevitable consequence of materiality assessments related to stakeholders, whose interests are aligned with the company for economic reasons, whether profits or wages (Di Vaio et al. 2022; PwC 2018). The overlap of economic data is consistent with a significant portion of the literature. Specifically, it can be noted that the top five most cited SDGs in ASIA's report align with four out of five (SDG 8, 13, 3, 9) of those identified in cross-sectoral meta-analyses. Similarly, three out of five SDGs—namely 1, 2, and 6—are confirmed to be underrepresented (PwC 2018).

Additionally, the positive outcomes observed in socio-economic data, as well as those related to the company's core business (i.e., waste collection), suggest a positive but narrowly focused impact of sustainability report publication. From this perspective, the company appears to perform well in terms of reducing workplace injuries and addressing the gender gap, despite the company has never had a female manager, and its environmental performance (which affects health outcomes) is not progressing in the desired direction. This confirms the intrinsic ambiguity of sustainability reports, which can obscure actual behavior through selective metrics, presenting changes that are either non-existent or significantly less substantial than they appear (Haffar and Searcy 2020). This partial alignment aligns with prior research (e.g., Bebbington and Unerman 2020), which highlights economic targets' dominance in CSR reporting, often at the expense of environmental objectives.

Our findings provide partial answers to the research question. ASIA s.p.a demonstrates alignment with several SDGs, particularly those linked to economic growth (SDG 8) and social well-being (SDGs 1, 4). However, the company's environmental performance remains misaligned with SDGs 6, 7, and 13. This highlights a structural weakness in integrating sustainability metrics across all relevant dimensions. Furthermore, when analyzing strictly environmental data, it becomes apparent that the company deviates, to varying degrees, from its own targets. A particularly emblematic case is SDG 13, related to greenhouse gas emissions, which, despite being the most frequently mentioned goal (in relation to the available indicators) in SR, shows a significantly negative trend in its evolution. Similarly, water consumption (SDG 6), plastic use (SDG 14), waste production (SDG 12), and energy consumption (SDG 7) exhibit the same negative pattern. This trend is masked by SDG 8, which measures green growth. As previously mentioned, when considered purely in terms of economic growth, the company shows an increase in both revenue and financial/operational solidity during the period under review, as evidenced by EBIT and EBITDA indicators (more information in Supporting Information S4). However, this economic growth is not accompanied by a proportional reduction in the company's environmental consumption. Thus, it can be concluded that the company represents a case of relative decoupling (Vadén et al. 2020; Parrique et al. 2019), where economic growth continues to be driven by an expansion of negative environmental impacts, even if at a relatively lower intensity. To improve alignment with environmental SDGs, ASIA s.p.a should adopt specific mitigation plans for climate action (SDG 13), including quantifiable targets for emission reductions and water consumption.

To bridge this gap, the parametrization approach outlined herein serves as a means to redefine corporate sustainability strategies in a way that is both quantifiable and internationally comparable. By integrating both quantitative and qualitative indicators directly linked to SDG 13 and SDG 6, companies can move beyond symbolic sustainability commitments and develop actionable strategies that align with local and global environmental priorities. To enhance alignment with SDGs, particularly in environmentally vulnerable cities like Naples, ASIA s.p.a should implement strategic measures that integrate sustainability into its core operations. First, the company must establish clear, quantifiable targets and align them with financial reporting, ensuring sustainability indicators (e.g., carbon footprint, water usage) are embedded in decision-making. Transparency can be improved by strengthening data disclosure and introducing external audits for accountability. Stakeholder engagement is crucial; collaborating with local governments, NGOs, and communities can help tailor sustainability efforts to urban challenges. Additionally, promoting gender-inclusive leadership and implementing sustainable supply chain practices will enhance corporate responsibility. To address SDG 13 (climate action), ASIA s.p.a should adopt science-based emissions reduction targets and increase investments in green technologies, such as the production of renewable energy. Finally, by reinforcing accountability mechanisms, ASIA s.p.a can move beyond symbolic commitments and create measurable, long-term sustainability impacts.

8 Conclusions

The results discussed in this paper lead to the conclusion that the publication of the SDGs has provided a significant impetus for the quantitative and qualitative improvement of sustainability reports. This influence is expected to grow in the coming years due to the increase of laws constraining, as theorized by institutional theories (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). However, the relationship between SR and the achievement of the SDGs is not as straightforward. As stated, the process of drafting sustainability reports risks aligning them too closely with financial reporting, where environmental and social accounting are treated merely as additional components. More critically, there is a risk that these reports are used primarily to gain public credibility rather than to enhance environmental performance. In other words, without a comprehensive environmental management plan based on systematic data collection, sustainability reports may become mere tools for corporate greenwashing. From this perspective, legitimacy theory can help explain the relation between SR and CSR in achieving SDGs (Suchman 1995).

Beyond the immediate context of waste management in Naples, this study offers broader implications for both academic inquiry and practical implementation. For scholars, the findings underscore the utility of integrating SR with the UN SDGs as a methodological framework to assess environmental governance at the urban level. Practitioners, particularly municipal policymakers and waste management authorities, may draw from this case study to enhance accountability, transparency, and strategic alignment with global sustainability benchmarks. From a policy perspective, the results suggest the need for stronger regulatory mandates to ensure that sustainability reports are not merely symbolic but are actively used as tools for planning and evaluation. However, the study is limited by its single-case focus, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Future research should consider comparative analyses across cities or regions to develop a more nuanced understanding of the institutional, cultural, and socio-political factors that shape the alignment between SR and SDGs. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could capture the evolution of this alignment over time, offering deeper insights into the dynamics of policy adaptation and organizational learning.

Acknowledgments

Raffaele Guarino was supported by the REACT-EU FSE DM 1061, specifically Actions IV.4 and IV.5 of PON 37 cycle. The author is grateful to ASIA spa for generously providing access to their data and for hosting an internship, which significantly contributed to this research. During the preparation of this work, the author(s) utilized the online AI-powered tool DeepL to enhance readability and language clarity. Following the use of this tool/service, the authors thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as necessary and assume full responsibility for the publication's content. Open access publishing facilitated by Universita degli Studi di Napoli Parthenope, as part of the Wiley - CRUI-CARE agreement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.