Is the Association Between Emotion Recognition and Social Functioning Mediated by Cognitive Empathy and Emotional Language? An Examination of School-Aged Autistic Children

ABSTRACT

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) face substantial challenges in understanding emotions, including difficulty in recognizing emotions through nonverbal cues, interpreting others' affective and mental states, and developing emotional vocabulary. Research suggests that the association between emotion recognition and social functioning is mediated by emotional language and cognitive empathy. However, this relationship remains underexplored in autistic children. Addressing this gap was the primary goal of this study, which comprised 116 autistic children (17 females), aged 7–10 (M = 8.26, SD = 0.76). Participants completed a comprehensive assessment battery, comprising multi-modal emotion recognition, cognitive empathy, and emotional language tasks. Social functioning was evaluated through naturalistic observations during free play, supplemented by a parent-reported standardized measure. Path analysis results revealed that after controlling for age, cognitive abilities, and autism severity, the relationship between emotion recognition and social functioning was mediated by cognitive empathy. Additionally, emotional language emerged as a contributing factor, enhancing cognitive empathy and further supporting its role in social functioning. These findings present an indirect path between emotion recognition and social functioning through emotional language and cognitive empathy, highlighting the importance of targeting these components in interventions aimed at promoting social communication and adaptive social skills in autistic children.

Summary

- The link between the ability to recognize emotions from nonverbal cues (such as facial expressions, body language, and vocal intonation) and everyday social functioning seems intuitive, but has been rarely studied in autistic children.

- This study sought to examine how these abilities relate to the social functioning of autistic children.

- Autistic children aged 7–10 completed a comprehensive assessment battery that included a multi-modal emotion recognition task, a cognitive empathy task, and an emotional language task.

- Social functioning was evaluated through naturalistic observations during free play, supplemented by a parent-reported standardized measure.

- Results showed that recognizing emotions is important for social functioning, but that its impact depends on the child's social understanding, that is, the ability to interpret others' affective and mental states in context.

- Understanding and using emotional language was found to improve social understanding, which in turn supported children's social behavior with peers.

- These findings highlight the importance of supporting autistic children's affective and cognitive understanding of emotions as well as their emotional vocabulary as menas to promote their social interactions.

1 Introduction

Understanding another person's emotions is a complex and multifaceted skill that integrates both sensory and cognitive components, requiring the interpretation of nonverbal cues and contextual information while drawing on prior knowledge and experiences (Arioli et al. 2018). This ability plays a key role in facilitating social functioning and nurturing relationships (Denham 2019). Research suggests that the perception of emotional cues in others is mediated through linguistic conceptualization and contextual interpretation, ultimately leading to a social response (Gendron and Feldman-Barrett 2018). This path, which was underexplored in autistic children, is the focus of the current study.

During social interactions, emotional information is conveyed through several nonverbal modalities, including facial expressions, gestures, and prosody (Gil et al. 2014). Research indicates that compared to their non-autistic (NA) peers, autistic children experience difficulties in detecting emotional cues across these modalities, when presented separately or simultaneously (Fridenson-Hayo et al. 2016; Leung et al. 2022; Todorova et al. 2019; Yeung 2022; Zhang et al. 2022). These difficulties are manifested over a wide range of emotions, including more basic (e.g., fear, anger) and more complex (e.g., pride, shame) emotions (Fridenson-Hayo et al. 2016).

Since emotional information is deciphered within a social context, emotion recognition represents only one aspect of emotional understanding. Another critical aspect encompasses the ability to adopt other's perspective and mentally represent their intentions, desires, beliefs and emotions in order to draw casual inferences about their behavior (Duradoni et al. 2023). This capacity is often referred to in the literature as either “affective Theory of Mind” (ToM) or “cognitive empathy.” Although these terms are closely related and sometimes used interchangeably, the current study adopts the term cognitive empathy, as it captures not only the mentalizing process involved in inferring others' emotional states, but also the interpersonal connectedness central to the empathy framework (Schurz et al. 2021), as well as its association with pro-social behavior (Dovidio and Banfield 2015). Autism research provides ample evidence of autistic individuals' difficulties to “read the mind” of NAs during social interactions and to discern socio-emotional contextual cues (Bamicha and Drigas 2022; Fitzpatrick et al. 2018; Pedreño et al. 2017).

The two constructs of emotion recognition through non-verbal cues and cognitive empathy are closely interconnected. Theoretically, and with the support of neurological evidence, emotion recognition has been considered to temporally precede the cognitive empathy, perspective-taking system (Dorris et al. 2022; Mitchell and Phillips 2015). This connection has been demonstrated in autism research, where difficulties in emotion recognition across different modalities have been found to associate with impaired cognitive empathy, highlighting the role of emotion recognition as a foundational component of empathic understanding (Altschuler et al. 2021; Metcalfe et al. 2019; Rueda et al. 2015). Moreover, atypical brain activation and connectivity within social brain networks have been linked to both emotional processing and cognitive empathy in autistic individuals (May et al. 2022). However, Gendron and Feldman-Barrett's (2018) “Theory of Constructed Emotion” (TCE), argues that the synchronization between perceiving emotional nonverbal cues and socio-emotional knowledge is mediated through the acquisition of verbal concepts to construct predictions about others' emotional states. They propose a “top-down” model of neural organization, where higher cortical regions generate predictions sent to lower regions, which are then corrected by incoming sensory input. This process suggests that the brain continuously predicts and adapts to incoming information based on prior expectations. Words and concepts serve as scaffolding, playing a crucial role in the formulation of these predictions (Feldman-Barrett 2017; Lindquist 2017).

The role of language as a bridge between emotion recognition and cognitive empathy introduces additional complexity for autistic children due to their diverse speech and language developmental profiles (Vogindroukas et al. 2022). Previous research has specifically examined autistic children's development of emotional language, i.e., their use of verbal concepts encompassing emotion-laden words, sentences, and text (Lartseva et al. 2015). These studies have highlighted atypical patterns in the ability of autistic children to encode and retain emotionally related words. While NA children showed an advantage in recalling emotional concepts compared to neutral stimuli over time, autistic participants did not exhibit the same benefit (Lartseva et al. 2015). Additionally, research assessing expressive emotional language through picture description or narrative tasks has found that autistic children and adolescents aged 5–19 used fewer emotional terms compared to their NA peers (Kauschke et al. 2016; Wiley.Teh et al. 2018). These findings align with results from emotion definition tasks, which demonstrated that autistic children aged 4–11 faced challenges in defining a broad range of emotions compared to NA children (Ben-Itzchak et al. 2016, 2018; Gev et al. 2017; Golan et al. 2010).

Autistic children clearly face challenges across various aspects of emotional development, with each component potentially contributing to their social difficulties, their ineffective interaction with NAs, and their struggle to navigate through social environments. This encompasses forming and maintaining relationships, understanding social norms and cues, and successfully engaging in social activities (Pallathra et al. 2018). While there is considerable research on the relationship between emotion recognition from nonverbal and social cues and social functioning in the NA population (Denham 2019), studies examining this connection in autism remain limited. A meta-analysis by Trevisan and Birmingham (2016) examined the association between emotion recognition and social functioning in autistic children. They found that autistic children's ability to recognize nonverbal emotional cues was positively correlated with age, nonverbal and verbal intelligence, theory of mind, and adaptive functioning, while negatively correlated with the severity of autism symptoms. However, these findings were limited in two key ways. First, emotion recognition was assessed only through facial expressions, excluding other nonverbal modalities and contextual understanding. Second, social functioning was inferred through broad adaptive functioning measures such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales and the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-II, which are based on informant reports and may fail to capture natural social behavior in real time.

The positive association between cognitive empathy and social functioning is well documented in NA children (Chiu et al. 2023; Ronchi et al. 2020; Rosello et al. 2020). Evidence also supports this association in autistic individuals, although cognitive abilities have been shown to moderate the strength of this relationship (Mao et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2022). Interestingly, Peterson et al. (2016) demonstrated that whereas in hearing impaired and typically developing children, theory of mind independently predicted social functioning, in autistic children, this relationship was indirect and mediated by language ability. This finding flags the key role of language in the socio-emotional processing of autistic children.

The role of language in autistic children's cognitive empathy has been studied extensively. Various aspects of linguistic abilities have been associated with cognitive empathy in autism (Tager-Flusberg et al. 2005) including pragmatic, lexical, and syntactic (Andrés-Roqueta and Katsos 2017; Durrleman and Franck 2015). Specifically for emotional language, Siller et al. (2014) have shown that autistic children's use of emotion-related terms was associated with their understanding of mental states. Overall, these findings suggest that language supports social functioning not just by enabling communication but also by fostering cognitive empathy abilities.

Considering this evidence, exploring the intricate interplay between emotion recognition and social functioning through emotional language and cognitive empathy is needed, particularly for autistic children who face unique challenges in these domains. By bridging these constructs, the current study aimed to provide a comprehensive exploration of the pathways connecting emotional and social abilities, offering insights into how these interrelated skills contribute to the broader context of social interactions and adaptive functioning in autistic children.

2 Research Objectives and Hypotheses

- Emotional measures will be positively correlated with social measures, suggesting that higher performance in emotional measures (emotion recognition, cognitive empathy, emotional language) will be linked to better social functioning in autistic children.

- The association between emotion recognition and social functioning in autistic children will be mediated through emotional language and cognitive empathy (accounting for cognitive abilities, age and level of autistic traits).

3 Method

3.1 Participants

Data was obtained from the baseline stage of a broader intervention study comprising 140 autistic children, recruited from special education classes within mainstream schools. All participants had received clinical diagnoses of ASD by a child psychiatrist/neurologist and a psychologist, according to DSM-5 criteria (APA 2022). Diagnoses were further corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2; Lord et al. 2012) with all children meeting the ADOS-2 cutoff for ASD. To ensure participants did not have intellectual impairments, inclusion criteria required a minimum score of at least two standard deviations below the mean on two subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV; Wechsler 2003): Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning. Of the initial cohort, 116 autistic children (17 girls, 99 boys) met these criteria and were included in the analysis (see Table 1).

| Descriptive statistics | Pearson correlation coefficients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional measures | Social functioning | |||||||||

| M | SD | ER | TEC | EDa | PI | PR | Unengaged | Engaged | ABAS-Sb | |

| Age | 8.27 | 0.76 | 0.23* | 0.20* | 0.23* | 0.093 | 0.042 | −0.063 | 0.096 | −0.28** |

| ADOS CSS | 8.68 | 1.01 | −0.101 | −0.23* | −0.19* | −0.017 | −0.035 | 0.019 | −0.007 | −0.142 |

| Matrix | 6.92 | 3.38 | 0.35** | 0.18* | 0.28** | 0.061 | 0.076 | −0.066 | 0.097 | 0.058 |

| Vocabulary | 7.10 | 2.95 | 0.26** | 0.34** | 0.41** | 0.090 | 0.009 | 0.087 | 0.035 | −0.082 |

| ER | 30.82 | 5.74 | 0.42*** | 0.43*** | 0.25** | 0.09 | −0.14 | 0.17 | −0.03 | |

| TEC | 16.22 | 2.18 | — | 0.50*** | 0.37*** | 0.29** | −0.20* | 0.24** | 0.13 | |

| ED1 | 8.05 | 5.74 | — | 0.25** | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.12 | −0.08 | ||

| PI | 6.67 | 5.23 | — | 0.65*** | −0.53*** | 0.68*** | 0.15 | |||

| PR | 6.79 | 5.04 | — | −0.52*** | 0.61*** | 0.15 | ||||

| Unengaged | 1.97 | 2.58 | — | −0.78*** | −0.13 | |||||

| Engaged | 5.97 | 3.58 | — | 0.07 | ||||||

| ABAS-S2 | 79.44 | 13.12 | — | |||||||

- Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

- Abbreviations: ABAS-S, adaptive behavior assessment system, social scale; ADOS CSS, autism diagnostic observation schedule—2nd edition, calibrated severity score; ED, emotion definition; ER, emotion recognition; PI, positive initiative; TEC, cognitive empathy measure; WISC, Wechsler intelligence scale for children test, 4th ed.

- a n = 114.

- b n = 104.

3.2 Instruments

Emotion recognition from nonverbal cues (Fridenson-Hayo et al. 2016): This task examined the recognition of 12 emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, pride, kindness, unfriendliness, shame, boredom, interest, and disappointment). The recognition of each emotion was tested through four items, comprising a facial expression video, a decontextualized vocal utterance, a body language video, and an integrative video clip presenting all modalities in context. For each item, 4 potential answers were presented. Participants received a score of 1 for each correct answer, with the total score ranging between 0 and 48 for the entire test. Internal consistency in the current study was α = 0.74. Also, a positive correlation was previously reported with an established facial emotion recognition task for both autistic (r = 0.52) and NA children (r = 0.40) (Fridenson-Hayo et al. 2016).

Test of emotion comprehension (TEC; Pons and Harris 2000): The TEC was used in the current study to assess cognitive empathy. Designed for children aged 3–12, the TEC evaluates foundational components of cognitive empathy, including the ability to understand the causes of emotions (e.g., desires, beliefs, and memory), to recognize the influence of contextual factors (e.g., external causes, moral considerations), and to grasp the complexity of emotional experiences (e.g., mixed emotions, emotional regulation). The TEC consists of short stories with gender-matched illustrations lacking nonverbal emotional cues. The child is asked to choose how a protagonist feels from four options. Scores range between 0 and 21. TEC is reported with high test–retest reliability (0.84; Pons et al. 2002) and good compatibility to cognitive and verbal skills (Tenenbaum et al. 2004).

Emotion definition task (adapted from Golan et al. 2010): This task examined participants' expressive emotional language. It included 12 emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, pride, kindness, unfriendliness, boredom, shame, disappointment, and frustration), for each of which participants were asked to define the emotion (for example: “Can yo explain what is happy”) and to give examples to a personal experience related to each of the emotions (e.g., “Can you describe a situation in which you felt happy?”). The definition and examples were audiotaped, and transcribed verbatim. Scores of 0, 1, or 2 were given to the definition of each emotion, following Gev et al. (2017). Hence, task scores ranged from 0 to 24. Scoring was conducted by two naïve trained judges. Average inter-rater agreement in the current study was 0.98.

Playground observation of peer engagement (POPE; Kasari et al. 2005): The POPE is a time-interval behavior coding system that evaluates socio-emotional functioning in natural settings. Twelve independent, naïve observers from the research team rated each participant on the playground during the school recess for a total of 10 min. Each minute was subdivided into 40 consecutive seconds of observation, followed by coding for the subsequent 20 s. The observers documented the child's level of engagement with peers on the playground (solitary, proximity, onlooking, parallel, parallel aware, joint engaged with peers, and involved in games and rules) in each interval. Following Kasari et al. (2005), playground engagement states were summed for a total proportion of intervals in each engagement state and then divided into two styles: unengaged (incorporating solitary and proximity) and engaged (incorporating joint engagement and games and rules). Coders also noted positive initiatives of the child towards other children, and positive and negative responses to peers' social overtures. Observers underwent eight sessions of training administered by the research coordinator and attained a reliability level of at least 80% in taped video observations prior to the beginning of the study. In line with earlier research employing the POPE (Gilmore et al. 2019; Locke et al. 2016; Santillan et al. 2019) reliability was collected on 20% of sessions during the study. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were notably high for all four measures (unengaged, engaged, positive initiatives and positive response), with an average of 0.96 and a range of 0.90-1.00, indicating strong agreement across the board.

Adaptive behavior assessment system, second edition (ABAS-II) (Gray and Carter 2013): The ABAS is a comprehensive, norm-referenced assessment of adaptive skills of individuals from birth to 89 years. In the current study, parents completed the social scale of the ABAS-II, comprising the social and leisure subscales. Standardized scores for the social scale have an average of M = 100 and a SD = 15. The internal consistency of the ABAS-II is high, with average reliability coefficients for the skill areas across age groups ranging between 0.85 and 0.97.

3.3 Procedure

The study received approval by Bar-Ilan university's IRB and by the Chief Scientist of the Israeli Ministry of Education. Upon receiving parental signed informed consent, trained professionals administered the two WISC-IV subtests and the ADOS-2 to all participants. Parents filled out the ABAS-II social scale online.

Next, 12 trained psychology undergraduates conducted assessments during two scheduled school visits. Each assistant was randomly assigned 10–12 participants. For each child, the assistant conducted two individual sessions, each lasting approximately 30 min, in a quiet room. During these sessions, participants completed the emotion recognition, TEC, and emotion definition tasks, in a counterbalanced order. Additionally, each assistant individually observed each of their assigned participants for 10 min during free play at recess, as part of the POPE task. Observations were scheduled randomly across the two visits to ensure even distribution within the available time.

4 Results

4.1 Correlation Analysis

The study measures included children's performance on emotional tasks—emotion recognition, emotion definition, and TEC, along with social functioning measures assessed through the POPE and ABAS-social scale scores. In addition to the examination of the correlations between the study measures, we have also examined the correlations of children's age, WISC-IV subtests' scores, and ADOS with the study measures (see Table 1).

As shown in Table 1, participants' age was positively associated with emotion recognition, emotion definition, and TEC scores, indicating that older children tended to perform better on these measures. Age was negatively associated with ABAS social scale, indicating that gaps in autistic children's social adaptive functioning increase with age, compared to their age group norms. Non-verbal cognitive skills, assessed by the matrix reasoning subtest, also showed significant positive correlations with emotion recognition, emotion definition, and TEC scores, suggesting that participants with higher non-verbal cognitive skills performed better in these domains. Similarly, verbal ability, measured by the Vocabulary subtest, was positively correlated with emotion recognition, emotion definition, and TEC scores. ADOS calibrated scores were negatively correlated with TEC and emotion definition scores, but not with emotion recognition scores.

In line with our first hypothesis, significant positive correlations were observed between the study measures. Emotion recognition was strongly associated with emotion definition, TEC, and positive initiatives scores, indicating that better emotion recognition was linked to improved performance in these areas. However, no significant correlations were observed between emotion recognition and other social functioning measures, such as positive responses, engagement levels, or ABAS-social scores. Similarly, emotion definition showed a positive correlation with both TEC and positive initiatives scores. Finally, the TEC demonstrated a significant positive correlation with all measures of social functioning observations, including positive initiatives, positive responses, and levels of engagement, emphasizing that higher TEC scores were associated with better social functioning outcomes. Contrary to our hypothesis, none of the emotional measures or observational social measures shown were correlated with the ABAS-social scale, which reflects parents' reports of their children's social abilities. Notably, the frequency of positive initiatives directed by children toward their peers emerged as the social functioning measure most strongly correlated with all emotional measures. Consequently, we selected positive initiatives as the primary indicator of social functioning for subsequent analyses.

4.2 Mediation Analyses

The second aim was to explore the relationship between emotion recognition and social functioning through emotional language and cognitive empathy. To achieve this, we first examined the mediation between emotion recognition and TEC via emotional language, as well as the mediation between emotional language and social functioning through TEC. Finally, we evaluated the integrated model connecting emotional recognition to social functioning.

To examine the role of emotion definition as a mediator between emotion recognition and TEC, a mediation analysis was conducted using Model 4 in the process software (Hayes 2018). The age of the participants, along with their scores on the matrix, vocabulary, and ADOS, were included as covariates in the analysis due to their significant correlations with emotion recognition and emotion definition. The results of the mediation analysis revealed a significant direct effect of emotion recognition on TEC (b = 0.08, SE = 0.03, t = 2.24, p = 0.027), as well as a significant effect of emotion recognition on emotion definition (b = 0.23, SE = 0.09, t = 2.61, p = 0.010), and a significant effect of emotion definition on TEC (b = 0.11, SE = 0.04, t = 2.87, p =0.005). The indirect effect, representing the mediation pathway from emotion recognition to TEC via emotion definition, was significant (b = 0.06, SE = 0.04, 95% CI: 0.008, 0.145).

Next, to examine the role of TEC as a mediator between emotion definition and positive initiatives, a mediation analysis was conducted using Model 4 in the process software (Hayes 2018). The age of the participants, along with their scores on the matrix, vocabulary, and ADOS, were included as covariates. The results of the mediation analysis revealed a non-significant direct effect of emotion definition on PI (b = 0.11, SE = 0.11, t = 1.02, p = 0.312). However, a significant effect of emotion definition on TEC (b = 0.11, SE = 0.04, t = 2.87, p = 0.005), and of TEC on PI (b = 0.74, SE =0.27, t = 2.77, p = 0.007) was found. The indirect effect, representing the mediation pathway from emotion definition to positive initiatives via TEC, was significant (b =0.09, SE = 0.04, 95% CI: 0.015, 0.179).

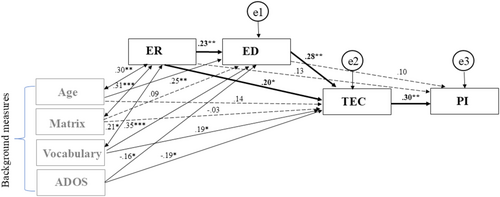

To examine the intricate relationships between emotion recognition, emotion definition, TEC and PI, we conducted a path analysis to examine the direct and indirect effects within the holistic model, incorporating the age of the participants, as well as their scores on the Matrix, Vocabulary, and ADOS, as covariates. The model fit was assessed using several goodness-of-fit indices: χ2/df ratio (CMIN), goodness of fit index (GFI), incremental fit index (IFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). According to Kline (2005), a good fit is indicated by a relatively small χ2/df ratio ≤ 3 and non-significance. Hoyle (1995) defined a good fit as GFI ≥ 0.90. Hair et al. (2010) defined a good fit as IFI and CFI ≥ 0.90, and Steiger (2007) indicated that a good fit is characterized by RMSEA ≤ 0.07. Figure 1 presents the full model.

The evaluation of the model fit revealed satisfactory results across several goodness-of-fit indices. The χ2/df ratio (CMIN) was 1.789, which is well below the threshold of 3, indicating an acceptable fit according to Kline (2005). The GFI was 0.95, surpassing the 0.90 benchmark, suggesting a good overall fit (Hoyle 1995). Additionally, both the IFI and CFI were 0.939 and 0.932, respectively, both exceeding the threshold of 0.90, which is indicative of a good fit (Hair et al. 2010). However, the RMSEA was 0.084, slightly above the ideal cutoff of 0.07 defined by Steiger (2007), suggesting a moderate fit. Taken together, these results suggest that the model fits the data reasonably well, although the RMSEA indicates room for improvement in model fit. To refine the model and enhance its parsimony, we have omitted the paths that were not significant or had a p-value greater than 0.10. Specifically, we excluded the paths from age to TEC, from WISC Matrix reasoning to TEC and emotion definition, and from emotion definition to PI. This revision yielded a RMSEA of 0.070, which is exactly at the ideal cutoff defined by Steiger (2007), suggesting an acceptable model fit.

The final model is depicted in Figure 1 and reveals two significant mediation pathways linking emotion recognition from non-verbal cues to social functioning (positive initiatives during free play) in autistic children. First, a mediation pathway was found through cognitive empathy, such that better emotion recognition predicted enhanced cognitive empathy, which in turn positively influenced social functioning. Second, an additional significant pathway emerged through emotional language: stronger emotion recognition predicted greater use of emotional language, which subsequently enhanced cognitive empathy and, ultimately, positively impacted social functioning.

5 Discussion

The main aim of this study was to test the interplay between emotional understanding components and social functioning in autistic children. The findings confirmed the hypothesis that cognitive empathy mediates the relationship between emotion recognition and social functioning. Additionally, emotional language emerged as a key factor in enhancing cognitive empathy. These findings further emphasize the importance of language in shaping social functioning and extend findings on typically developing children to the context of autism.

Previous research highlights significant challenges in emotional understanding among autistic individuals (Bamicha and Drigas 2022; Fridenson-Hayo et al. 2016; Gev et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2022), which are thought to be closely linked to deficits in social functioning, a defining feature of autism (Denham 2019). Studies consistently demonstrate strong correlations between the affective perception involved in emotion recognition and the cognitive process of inferring others' mental states—cognitive empathy (Altschuler et al. 2021; Metcalfe et al. 2019; Mitchell and Phillips 2015) as well as between cognitive empathy and social functioning (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al. 2017; Chiu et al. 2023; Mao et al. 2023). However, the route from the perception of emotional cues, through its conceptualization in context, to its manifestation in social behavior has scarcely been studied. Moreover, Gendron and Feldman-Barrett's (2018) TCE posits that emotional language serves as a key mediator in the relationship between emotion recognition and cognitive empathy. However, this theory has not been tested among autistic individuals, many of whom show emotional language difficulties alongside challenges both in verbal and in nonverbal communication (Groen et al. 2008).

Building on this evidence, we examined how emotion recognition in autistic children contributes to social functioning through the mediation of emotional language and cognitive empathy. The results of the first mediation analysis confirmed a direct association between emotion recognition from non-verbal cues and cognitive empathy, as well as an indirect association mediated by emotional language. These findings align with TCE (Gendron and Feldman-Barrett 2018), highlighting the role of language as a bridge between the sensory perception of emotional cues and socio-emotional knowledge. The second mediation analysis revealed that the relationship between emotional language and social functioning was mediated through cognitive empathy. The entire theoretical model was examined through a path analysis testing the relationship between emotion recognition and social functioning in autistic children, while accounting for background characteristics such as age, cognitive abilities, and level of autistic traits. The findings validated the proposed theoretical framework, confirming the central role of cognitive empathy in mediating the relationship between emotion recognition and social functioning. Moreover, they highlighted the significant contribution of emotional language in enhancing cognitive empathy and its indirect influence on social functioning among autistic children. These results align with prior research demonstrating the connection between various aspects of language and cognitive empathy in autism (Andrés-Roqueta and Katsos 2017; Durrleman and Franck 2015; Siller et al. 2014). Our findings reinforced the view that, particularly for autistic individuals, language serves as a distinct compensatory tool to support socio-emotional understanding. Hence, language contributes to social functioning not only through speech production but also by fostering the development of cognitive empathy (Eigsti et al. 2016; Eigsti and Irvine 2021).

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the children's social functioning, the current study utilized two assessment measures: parent-report questionnaires and behavioral observations during the children's free-play time. Interestingly, we found no correlation between parental reports of children's social abilities and observational measures. This discrepancy may stem from the different perspectives captured by these tools: while parental reports offer a broader, longitudinal view of the child's social abilities across various contexts and may be influenced by the parent–child relationship dynamics, observational measures are assessed impartially by a researcher but provide a snapshot of the child's performance at a specific moment (Lemler 2024; Moens et al. 2018). This distinction between the two types of assessment tools highlights the complexity of measuring social functioning and the importance of considering multiple sources of data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a child's social abilities. Furthermore, all emotional measures (emotion recognition, cognitive empathy, and emotional language) and social functioning observations were conducted in a standardized manner, involving direct assessment of the children at a specific point in time by an objective researcher. These similarities may explain why the correlations between emotional measures and social functioning were found significant only with natural play-time observations and not with parental reports.

Among the measures collected through observations of the children's social behavior, positive initiatives demonstrated the strongest correlation with emotional measures. This measure reflects the child's motivation to actively engage with peers and to actively and positively take the initiative in social interactions. Research suggests that when children initiate requests, they gain greater control over their environment by accessing their needs and desires, which subsequently increase social interaction (Aal Ismail et al. 2022; Koegel et al. 2014; Mohammadzaheri et al. 2021). In contrast, the second observational measure, positive responses, represents a more passive dimension of social engagement. Positive responses capture the child's ability to react to others' social overtures, even if those reactions are not always appropriate. While this measure provides valuable insight into the child's receptiveness to social interactions, it reflects a reactive rather than proactive form of social behavior. Notably, no significant association was found between emotion recognition and positive responses. This finding is particularly interesting given that emotion recognition, as a receptive skill, might be expected to also align with reactive forms of social functioning. These findings suggest that the effects of emotion recognition on social behavior may be mediated by additional factors not assessed in the current study, such as social motivation, self-confidence, attentional control, or the capacity to process social information in real time. These factors may play a differential role in children's social initiative versus social response (Itskovich et al. 2020; Øzerk et al. 2021). Moreover, the measurement of engagement types (engaged and unengaged) was constrained by a limited range, as it was based on only 10 min of coded observations. This restriction may have diminished its ability to capture meaningful variability in behavior. In contrast, the positive initiatives variable was not subject to a maximum limit, enabling it to more accurately reflect individual differences among the children and their connections to emotional measures.

Finally, an examination of the correlations between background variables and measures of emotional and social functioning revealed associations with emotional measures but no direct correlation with social functioning outcomes, whether assessed through observations or parent reports. This finding suggests that the influence of background variables is mediated through emotional functioning. In other words, the child's age, cognitive abilities, and level of autistic traits may affect children's emotional understanding, which in turn shapes their level of social functioning.

Our results carry significant clinical implications, particularly for the development of intervention programs tailored for autistic individuals. Many existing interventions focus predominantly on improving the ability to recognize emotions through nonverbal cues (Berggren et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2022). While such skills are undoubtedly important, this study highlights that, in addition to emotion recognition, addressing cognitive and linguistic aspects of socio-emotional development may also be needed to bring about meaningful improvements in social functioning.

6 Limitations and Future Directions

Alongside the contributions presented above, it should be acknowledged that certain factors that could influence the path from emotion recognition to social functioning were not accounted for in this study. Emotion regulation may play a significant role in autistic children's social functioning, as previous studies have shown (Cibralic et al. 2019; Goldsmith and Kelley 2018). Executive functioning, essential for goal-directed behavior and effective communication, is another potential factor worth examining (Bottema-Beutel et al. 2019). Additionally, gender differences pose a limitation due to our overrepresentation of boys compared to girls, consistent with patterns in autism research (Barsotti et al. 2023). Further research is needed to enhance our comprehension of the intricate relationship between emotion recognition and social functioning in autistic children, as well as within the specific context of gender.

7 Conclusion

The findings of this study uncover the complex pathway linking emotion recognition and social functioning among autistic children. These insights have important implications for the development of intervention programs. By adopting a holistic approach that integrates emotion recognition, emotional language, and cognitive empathy, such programs may address the diverse needs of autistic children more effectively, equipping them with the skills to navigate social situations and achieve meaningful improvements in their emotional and social outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants and their families for their time and commitment to this study. We are thankful to the school administrators and school staff for their support in facilitating the research process. We are grateful to Dr. Shlomit Shnitzer-Meirovich for her assistance with statistical analysis. Finally, we acknowledge the hard work and dedication of our research team, whose efforts were crucial to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.