Associations between parental psychiatric disorders and autism spectrum disorder in the offspring

Yi-Ling Chien and Chi-Shin Wu contributed equally to this work.

Funding information: Chang Gung Medical Foundation, Grant/Award Numbers: CMRPG3K1371, CMRPG3J0121, CMRPG3F0361, CMRPG3F1711–3; Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan; National Health Research Institutes, Grant/Award Numbers: CG-110-GP-01, PH-111-PP-08; Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, Grant/Award Numbers: MOST 109-2314-B-182-042-MY3, MOST 106-2314-B-182-051-MY3, MOST 107-2314-B-400-031-MY3

Abstract

Whether parental psychiatric disorders are associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in offspring has remained inconclusive. We examined the associations of parental psychiatric disorders with ASD in offspring. This population-based case–control study used Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database to identify a cohort of children born from 2004 to 2017 and their parents. A total of 24,279 children with ASD (diagnostic ICD-9-CM code: 299.x or ICD-10 code F84.x) and 97,715 matched controls were included. Parental psychiatric disorders, including depressive disorders, bipolar spectrum disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, substance use disorders, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and adjustment disorders were identified. Conditional logistic regressions with covariate adjustment were performed. The results suggest that parental diagnosis with any of the psychiatric disorders is associated with ASD in offspring (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.45, 95%CI: 1.40–1.51 for mothers; and AOR = 1.12, 95%CI: 1.08–1.17 for fathers). ASD in offspring was associated with schizophrenia, depressive disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, adjustment disorders, ADHD and ASD in both parents. The relationship between parental psychiatric disorders and the timing of the child's birth and ASD diagnosis varied across the different psychiatric disorders. The present study provides supportive evidence that parental psychiatric disorders are associated with autistic children. Furthermore, because the associations between parental psychiatric disorders and the timing of child's birth and ASD diagnosis varied across psychiatric disorders, the observed relationships may be affected by both genetic and environmental factors. Future studies are needed to disentangle the potential influence of genetic and environmental factors on the observed associations.

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impaired social interaction, communication, and restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests. The overall prevalence is estimated at around 1% of the population worldwide (Newschaffer et al., 2007), and has increased gradually to 1 in 44 children in recent decades (Maenner et al., 2021). Individuals with ASD have an increased risk of developing major psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia spectrum, bipolar, or major depressive disorders (Chien et al., 2021).

Studies have reported that the heritability of ASD ranges from 50% to 90% (Sandin et al., 2014; Sandin et al., 2017; Tick et al., 2016). The underlying genetic etiology of most non-syndromic ASD, which is not caused by chromosome aberration, single gene disorder, or other genetic syndrome, is not yet fully understood. Previous genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have well documented the genetic etiology of ASD (Kuo et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016). In a Taiwanese Han population, Kuo et al. performed a two-stage GWAS that revealed ASD related susceptible genes and variants (Kuo et al., 2015). In another study among East Asian populations, Liu et al. conducted a two-stage GWAS that identified several known and novel candidate genes related to ASD (Liu et al., 2016). One case–control study using genome-wide single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium demonstrated coheritability between ASD and major psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar, and depressive disorders (Lee et al., 2013), suggesting that high comorbidity between ASD and major psychiatric disorders may be attributable to shared genetic etiology. Recent studies further demonstrated that being born to parents with psychiatric disorders, including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, neurotic disorder, substance use disorders, and eating disorder increased the probability of ASD in offspring (Birmaher et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2020; Hviid et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2021; Rai et al., 2013). Previous findings have suggested cross-generational associations between parental psychiatric disorders and ASD among offspring. In contrast, other studies have revealed null associations between ASD in offspring and parental schizophrenia (Daniels et al., 2008), substance use disorders (Daniels et al., 2008; Fairthorne et al., 2016), bipolar disorders (Birmaher et al., 2010; Goetz et al., 2017), and depressive disorders (Daniels et al., 2008; Rai et al., 2013). These inconsistent findings might be due to small sample sizes and confounding factors. For example, parental age at delivery and socioeconomic status could confound the associations (Hultman et al., 2011; Sandin et al., 2012). Pregnancy complications, which are relatively common among mothers with psychiatric disorders (Sommer et al., 2021), might also potentially lead to an increased likelihood of ASD in offspring (Chien et al., 2019). The associations between ASD among offspring and psychiatric disorders among their parents varied across different psychiatric disorders, thereby leading to discordant results across studies.

To date, especially considering the increasing prevalence of ASD among children, few studies have comprehensively explored the associations between diverse psychiatric disorders in parents and ASD in offspring (Daniels et al., 2008; Hviid et al., 2013; Jokiranta et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2019). In those studies, the associations between parental psychiatric disorders and ASD in offspring were shown to be influenced by not only genetic factors, but environmental (or non-genetic) factors. Rearing a child with ASD could be highly stressful, which may precipitate the development of psychiatric disorders in caregivers (Zablotsky et al., 2013). Thus, there is a strong need to investigate temporal associations of parental psychiatric diagnosis with child's birth and ASD diagnosis to disentangle the genetic and environmental contributions, which could lead to prevention and more tailored interventions and treatments based on greater awareness.

To test for and better understand the association of various parental psychiatric disorders with ASD in offspring, we assessed the diverse types of parental psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar spectrum disorder, depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, adjustment disorder, substance use disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and ASD. This study aimed to examine the associations of those select parental psychiatric disorders with ASD in offspring, and to investigate the temporal associations between these various parental psychiatric disorders and the timing of a child's birth and/or ASD diagnosis.

METHODS

Data source

Data for this study was extracted from the medical claims database derived from Taiwan's National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). Approximately, 99.8% of the Taiwanese population have been enrolled in NHIRD since 2009. The available data collected in this claims database include information related to the beneficiaries' demographic characteristics, medical contacts, diagnoses based on International Classification of Diseases (ninth revision (ICD-9) codes, prior to December 31, 2015 and thereafter using tenth revision (ICD-10) codes) and prescription records, etc. The accuracy of clinical diagnosis for common psychiatric disorders has been validated elsewhere (Wu et al., 2020). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan.

Study population

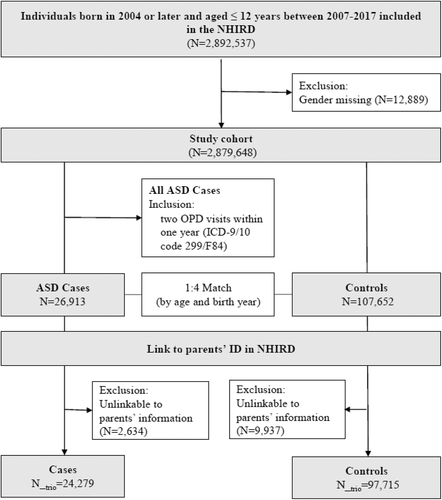

The study cohort included children with a diagnosis of ASD (ICD-9-CM code: 299.x or ICD-10 code F84.x), born between 2004–2017, and enrolled in the NHIRD between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2017. Four control children were randomly selected for each case with ASD and matched by sex and birth year. We linked parent data to the study children using Taiwan's Maternal and Child Health Database (MCHD), which allows for determining familial relationships between parents and children. We excluded those with missing information for sex and identification of the mother or father. A total of 24,279 children with ASD and 97,715 comparison subjects were included in the subsequent analysis. The flowchart of participant enrollment is shown in Figure 1.

Parental psychiatric diagnosis

Parental psychiatric diagnoses were identified based on at least two outpatient or one inpatient claims record between 2007 and 2017. Supplementary Table 1 provides the ICD-9 and ICD-10 CM codes for the list of psychiatric disorders investigated in this study. The examined psychiatric disorders include: schizophrenia, bipolar spectrum disorders (bipolar disorders and cyclothymia), depressive disorders (major depressive disorder, persistent depressive disorder, and depressive disorder, unspecified), anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia disorder), obsessive–compulsive disorder, adjustment disorders, substance use disorders (alcohol or drug use disorders), ADHD, and ASD. Parents, either fathers or mothers, diagnosed with any of the above-mentioned psychiatric disorders were defined as having a psychiatric disorder. The incident date of the diagnosed psychiatric disorders was defined as the date of the first diagnostic record.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of parents of children with and without ASD were compared using crude logistic regression analyses. We performed logistic regression to estimate the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the association between parental psychiatric disorders and offspring ASD. The adjusted covariates included parent's age at delivery, employment status, and urbanization (Liu et al., 2006), monthly income and all other psychiatric disorders. Of note, we assessed the associations between mothers' and fathers' psychiatric diagnoses separately, with ASD in the offspring.

Logistic regression models with covariate adjustment were employed to investigate the timing of the parent's psychiatric diagnosis in relation to the timing of the child's birth and ASD diagnosis. For inclusion in the models, we used the date of the first diagnosis of each investigated psychiatric disorder to define which time group a parent was assigned to and limited assignment to one time group. For example, if a parent had a specific psychiatric diagnosis before the child's birth, the parent was not included in the models for the time group between the child's birth and ASD diagnosis or after the child's ASD diagnosis. In addition, the time period that children were born was identical to the time period that parental psychiatric conditions were diagnosed. We assumed that a reasonable minimum age requirement for children to be followed so they could have ASD was 2 years old, and that a reasonable time for parents to be followed for psychiatric diagnosis was 1 year. Thus, we carried out the subsequent analyses by restricting the data to children born 2008–2015 for the period “before child's birth”; children born 2007–2015 for the period “between birth to ASD diagnosis”; and children born 2004–2014 for the period “after child's ASD diagnosis”.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Statistical significance was assessed using a 95% CI or p-value <0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 121,994 children (24,279 children with ASD and 97,715 matched controls) were identified for inclusion in the present study. Figure 1 depicts the flow chart for identifying the study cohort. Among children with ASD, 82.6% were boys. In all, 81.9% were diagnosed with ASD before the age of 6 years and 18.1% were diagnosed after age 6 years. Both parents of the children with ASD were older, more likely to live in an urban area, and had a higher income compared to those in the comparison group (Table 1). Compared to parents of control group children, mothers of children with ASD were more likely to be unemployed while fathers were more likely to be employed (Table 1). Children with ASD had higher rates of low birthweight, preterm birth, and cesarean delivery, individually. Mothers of children with ASD also had a higher percentage of complications during pregnancy, including gestational hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

| Cases (N = 24,279) | Controls (N = 97,715) | OR (95% CI) | pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||||

| Maternal baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Age at delivery (years) | ||||||

| <30 | 8131 | (34.81) | 41,288 | (43.19) | 1.00 | |

| 30–40 | 14,314 | (61.28) | 51,902 | (54.30) | 1.40 (1.36–1.44) | <0.001 |

| 40+ | 914 | (3.91) | 2398 | (2.51) | 1.94 (1.79–2.10) | <0.001 |

| Unemployment | 8236 | (35.26) | 32,868 | (34.39) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.012 |

| Urbanization | ||||||

| Low | 1053 | (4.51) | 6869 | (7.19) | ‘1.00 | |

| Median | 6165 | (26.39) | 28,722 | (30.05) | 1.40 (1.30–1.50) | <0.001 |

| High | 16,145 | (69.10) | 60,004 | (62.77) | 1.76 (1.64–1.88) | <0.001 |

| Insured amount, NTD | ||||||

| <20,000 | 6980 | (29.88) | 30,218 | (31.61) | ‘1.00 | |

| 20,000–40,000 | 10,790 | (46.18) | 47,267 | (49.44) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.488 |

| 40,000–60,000 | 4327 | (18.52) | 14,464 | (15.13) | 1.30 (1.24–1.35) | <0.001 |

| 60,000+ | 1266 | (5.42) | 3647 | (3.82) | 1.50 (1.40–1.61) | <0.001 |

| Paternal baseline characteristics | ||||||

| Age at delivery (years) | ||||||

| <30 | 3938 | (17.00) | 21,934 | (23.07) | ‘1.00 | |

| 30–40 | 15,442 | (66.66) | 61,563 | (64.74) | 1.40 (1.34–1.45) | <0.001 |

| 40+ | 3785 | (16.34) | 11,592 | (12.19) | 1.82 (1.73–1.91) | <0.001 |

| Unemployment | 4226 | (18.24) | 18,849 | (19.82) | 0.90 (0.87–0.94) | <0.001 |

| Urbanization | ||||||

| Low | 1035 | (4.47) | 6980 | (7.34) | ‘1.00 | |

| Median | 6490 | (28.02) | 30,474 | (32.05) | 1.44 (1.34–1.54) | <0.001 |

| High | 15,640 | (67.52) | 57,634 | (60.61) | 1.83 (1.71–1.96) | <0.001 |

| Insured amount, NTD | ||||||

| <20,000 | 5515 | (23.81) | 24,915 | (26.20) | ‘1.00 | |

| 20,000–40,000 | 8948 | (38.63) | 41,053 | (43.17) | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 0.414 |

| 40,000–60,000 | 5714 | (24.67) | 20,588 | (21.65) | 1.25 (1.20–1.31) | <0.001 |

| 60,000+ | 2988 | (12.90) | 8533 | (8.97) | 1.58 (1.50–1.67) | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy and parturition | ||||||

| Low birthweight (<2500 gm) | 1897 | (7.81) | 4836 | (4.95) | 1.64 (1.55–1.73) | <0.001 |

| Preterm birth (GA <37 weeks) | 2276 | (9.37) | 6615 | (6.77) | 1.43 (1.36–1.51) | <0.001 |

| Cesarean delivery | 8588 | (35.37) | 31,642 | (32.38) | 1.15 (1.12–1.19) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension complicating pregnancy | 367 | (1.51) | 1171 | (1.20) | 1.27 (1.12–1.42) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus complicating pregnancy | 509 | (2.10) | 1776 | (1.82) | 1.16 (1.05–1.28) | 0.004 |

- Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; NTD, New Taiwan Dollar, current exchange rate for 1 USD to NTD was around 30 in 2017; GA, gestational age; OR, odds ratio.

- a p values less than 0.05 are shown in bold.

Table 2 shows the associations between mothers and fathers with psychiatric disorders, separately, and ASD in the offspring. Generally, parental psychiatric disorders were more prevalent in families of children with ASD than those in the control group. Diagnosis with any of the included psychiatric disorders among the parents was positively associated with ASD in the offspring (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.40–1.51 for mothers; and AOR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.08–1.17 for fathers). The observed magnitude of the associations among fathers was lower than that among mothers. When further examining each psychiatric disorder, diagnosis with schizophrenia, depressive disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, adjustment disorders, ADHD, and ASD among the parents was significantly associated with ASD in the offspring compared to their counterparts (Table 2). Only maternal bipolar spectrum disorders were found to be associated with ASD in offspring. There was no association between parental anxiety disorders and substance use disorders and ASD in offspring.

| Cases | Controls | AORa (95% CI) | Case | Control | AORb (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| Maternal psychiatric disorders | Paternal psychiatric disorders | |||||||||

| Any psychiatric disorder | 4392 | (18.09) | 13,237 | (13.55) | 1.45 (1.40–1.51)c | 3796 | (15.63) | 14,247 | (14.58) | 1.12 (1.08–1.17) |

| Schizophrenia | 120 | (0.49) | 250 | (0.26) | 1.55 (1.24–1.94) | 102 | (0.42) | 272 | (0.28) | 1.48 (1.17–1.86) |

| Bipolar spectrum disorders | 750 | (3.09) | 1839 | (1.88) | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 401 | (1.65) | 1231 | (1.26) | 1.11 (0.97–1.27) |

| Depressive disorders | 1956 | (8.06) | 5064 | (5.18) | 1.45 (1.35–1.55) | 1000 | (4.12) | 3218 | (3.29) | 1.17 (1.07–1.27) |

| Anxiety disorders | 911 | (3.75) | 2693 | (2.76) | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | 641 | (2.64) | 2176 | (2.23) | 1.03 (0.94–1.14) |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 93 | (0.38) | 178 | (0.18) | 1.47 (1.14–1.91) | 62 | (0.26) | 152 | (0.16) | 1.35 (1.00–1.82) |

| Adjustment disorders | 528 | (2.17) | 1175 | (1.20) | 1.52 (1.37–1.70) | 324 | (1.33) | 849 | (0.87) | 1.42 (1.24–1.62) |

| Substance use disorders | 330 | (1.36) | 1201 | (1.23) | 0.99 (0.88–1.13) | 1369 | (5.64) | 6067 | (6.21) | 0.93 (0.87–0.99) |

| ADHD | 52 | (0.21) | 52 | (0.05) | 2.98 (2.00–4.44) | 57 | (0.23) | 70 | (0.07) | 2.96 (2.07–4.23) |

| ASD | 9 | (0.04) | 1 | (0.00) | 20.98 (2.58–170.62) | 12 | (0.05) | 3 | (0.00) | 15.35 (4.25–55.50) |

- Abbreviation: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CI: confidence interval.

- a Variables included in the adjusted models: all maternal baseline characteristics and the other listed maternal psychiatric disorders.

- b Variables included in the adjusted models: all paternal baseline characteristics and the other listed paternal psychiatric disorders.

- c p value less than 0.05 is indicated in bold.

Table 3 shows the temporal relationship between parental psychiatric disorders and the three time-windows (i.e., before child's birth, between child's birth and ASD diagnosis, and after child's ASD diagnosis) analyzed. We found that maternal bipolar spectrum disorders and depressive disorders were consistently associated with ASD in offspring across these three time-windows. Maternal anxiety disorders and adjustment disorders were consistently associated with ASD in offspring for the time periods before the child's birth and after child's ASD diagnosis. Significant associations between parental schizophrenia and offspring's ASD were found for two of the time periods before the child's birth and after child's ASD diagnosis. Positive associations with paternal adjustment disorders were noted for the time periods after the child's birth. A significant association between maternal substance use disorders and ASD in offspring was only observed during the time period before the child's birth. In contrast, paternal substance use disorders were inversely associated with ASD in offspring after the child's ASD diagnosis (Table 3).

| Before child's birth | Between birth and ASD diagnosis | After child's ASD diagnosis | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | AOR (95% CI) | Cases | Controls | AOR (95% CI) | Cases | Controls | AOR (95% CI) | |||||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | ||||

| Maternal psychiatric disordersa | |||||||||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 31 | (0.20) | 49 | (0.08) | 1.89 (1.20–3.00)c | 23 | (0.13) | 51 | (0.07) | 1.24 (0.61–2.49) | 53 | (0.23) | 115 | (0.12) | 1.64 (1.17–2.28) |

| Bipolar spectrum disorders | 72 | (0.47) | 131 | (0.21) | 1.47 (1.09–1.98) | 103 | (0.59) | 214 | (0.31) | 1.68 (1.26–2.24) | 525 | (2.25) | 1407 | (1.50) | 1.21 (1.09–1.35) |

| Depressive disorders | 445 | (2.93) | 1084 | (1.78) | 1.29 (1.14–1.45) | 433 | (2.48) | 1196 | (1.70) | 1.19 (1.02–1.39) | 811 | (3.48) | 2118 | (2.26) | 1.38 (1.24–1.54) |

| Anxiety disorders | 150 | (0.99) | 333 | (0.55) | 1.22 (1.12–1.34) | 157 | (0.90) | 470 | (0.67) | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) | 536 | (2.30) | 1674 | (1.79) | 1.20 (1.12–1.29) |

| Adjustment disorders | 74 | (0.49) | 169 | (0.28) | 1.34 (1.01–1.77) | 106 | (0.61) | 270 | (0.38) | 1.20 (0.91–1.60) | 288 | (1.24) | 639 | (0.68) | 1.58 (1.37–1.82) |

| Substance use disorders | 75 | (0.49) | 187 | (0.31) | 1.39 (1.06–1.82) | 70 | (0.40) | 214 | (0.31) | 1.19 (0.87–1.64) | 159 | (0.68) | 695 | (0.74) | 0.85 (0.71–1.01) |

| Paternal psychiatric disordersb | |||||||||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 34 | (0.22) | 81 | (0.13) | 1.53 (1.02–2.31) | 15 | (0.09) | 49 | (0.07) | 1.14 (0.63–2.04) | 29 | (0.12) | 68 | (0.07) | 1.75 (1.13–2.72) |

| Bipolar spectrum disorders | 39 | (0.26) | 105 | (0.17) | 1.26 (0.86–1.84) | 52 | (0.30) | 123 | (0.18) | 1.38 (0.99–1.94) | 289 | (1.24) | 921 | (0.98) | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) |

| Depressive disorders | 215 | (1.42) | 682 | (1.12) | 1.07 (0.90–1.26) | 230 | (1.32) | 708 | (1.01) | 1.14 (0.97–1.34) | 411 | (1.76) | 1431 | (1.53) | 1.08 (0.94–1.24) |

| Anxiety disorders | 107 | (0.71) | 332 | 0.544 | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 124 | (0.71) | 441 | 0.629 | 1.02 (0.92–1.13) | 337 | (1.45) | 1245 | (1.33) | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) |

| Adjustment disorders | 51 | (0.34) | 178 | (0.29) | 1.05 (0.76–1.44) | 77 | (0.44) | 179 | (0.26) | 1.52 (1.15–1.99) | 165 | (0.71) | 435 | (0.46) | 1.41 (1.17–1.70) |

| Substance use disorders | 239 | (1.58) | 980 | (1.61) | 0.95 (0.83–1.10) | 396 | (2.27) | 1486 | (2.12) | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 607 | (2.61) | 3046 | (3.25) | 0.84 (0.77–0.92) |

- Abbreviation: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

- a Variables included in the adjusted models: all maternal baseline characteristics and the other listed maternal psychiatric disorders.

- b Variables included in the adjusted models: all paternal baseline characteristics and the other listed paternal psychiatric disorders.

- c p values less than 0.05 are shown in bold.

DISCUSSION

This population-based case–control study is one of few published studies to comprehensively analyze the associations between diverse types of psychiatric disorders in parents and ASD in their offspring. Our findings suggest that parental psychiatric disorders, specifically schizophrenia, depressive disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, adjustment disorders, ADHD, and ASD were significantly associated with ASD in offspring. The overall magnitude of the observed associations was higher among mothers than fathers. The temporal relationship between parents' psychiatric diagnoses and the timing of their child's birth and ASD diagnosis varied across the different psychiatric disorders investigated in this study. More specifically, maternal bipolar spectrum disorders and depressive disorders were consistently associated with ASD in offspring across the three observed time-windows. The identified associations for the time periods before the child's birth and after child's ASD diagnosis were with parental schizophrenia. The noted associations for the time periods after the child's birth were with paternal adjustment disorders. Maternal substance use disorders were associated with ASD in offspring before the child's birth. A significant association between maternal anxiety disorders and adjustment disorders and ASD in offspring was only observed for the time periods before child's birth and after child's ASD diagnosis. In contrast, paternal substance use disorders were inversely associated with ASD in offspring after child's ASD diagnosis.

Our findings are consistent with most previous studies, which showed that psychiatric disorders were more common among the parents and/or first-degree relatives of ASD children (Chen et al., 2020; Fairthorne et al., 2016; Hviid et al., 2013; Jokiranta et al., 2013; Larsson et al., 2005; Liang et al., 2021; Rai et al., 2013; Sullivan et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2019). Although two prior studies reported null associations between parental psychiatric disorders and ASD in offspring (Birmaher et al., 2010; Goetz et al., 2017), their findings could be in part attributable to small sample size. Our findings provide indirect evidence to support that genetics play a role in the observed associations between parental psychiatric disorders and ASD in the offspring. These associated psychiatric disorders in parents might possibly share similar genetic etiology with ASD in offspring (Lee et al., 2013).

Associations between parental schizophrenia and ASD in offspring were mostly reported in Scandinavian countries of Northern Europe, such as Sweden (Sullivan et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2019), Demark (Hviid et al., 2013; Larsson et al., 2005), and Finland (Jokiranta et al., 2013). The observed association of parental schizophrenia with ASD in offspring in this study is in line with the findings of these previous studies, suggesting that such associations could be generalizable to Asian populations. A recent study demonstrated genetic correlations between schizophrenia and autism in an East Asian population (Lam et al., 2019). Our results regarding a cross-generational association of schizophrenia before the child's birth provides further supportive evidence that genetic influence may play a role in the observed association.

To date, a limited number of studies have explored the heritability of obsessive–compulsive disorder and ASD (Meier et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2019). These two disorders share some symptoms, such as repetitive behaviors, inflexibility with routines, and fixed interests as well as common genetic architecture (O'Connell et al., 2018). Our findings suggest that there is a cross-generational association between obsessive–compulsive disorder and ASD. Similarly, the findings from a recent twin study suggest that ADHD and ASD share clinical manifestations and some degree of genetic heritability (Laura Ghirardi et al., 2019). In fact, several cohort studies have also shown familial co-aggregation of ASD and ADHD (L Ghirardi et al., 2018; Jokiranta et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2021); and our findings for the associations between parental ASD and ADHD and ASD in offspring are consistent with these studies. However, because the number of parental cases of ASD in our study was small, this finding should be interpreted with caution.

Meanwhile, a number of studies have documented associations between maternal depressive disorders and ASD in offspring (Chen et al., 2020; Daniels et al., 2008; Hviid et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2021; Rai et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2019); however, associations with paternal depression (Daniels et al., 2008; Rai et al., 2013) have remained inconclusive. One meta-analysis assessed that paternal depressive disorders were not significantly associated with ASD in offspring (Ayano et al., 2019). Although our study identified an association with paternal depressive disorders, the magnitude of the association was smaller among fathers than mothers. This weak association identified by others might be partially explained by insignificant results in some studies with small sample sizes (Daniels et al., 2008; Rai et al., 2013). A similar pattern was noted for bipolar spectrum disorders. We found that only maternal bipolar spectrum disorders were associated with ASD in offspring, which is consistent with findings from another study of Taiwan's population (Liang et al., 2021).

Overall, the magnitude of the associations among mothers was higher than that among fathers, which implicates two possible mechanisms. Intrauterine exposure might play a role in the development of ASD in offspring through epigenetic mechanisms. Exposure to stress or psychiatric disorders during pregnancy might impact epigenetic status, consequently leading to an increased likelihood of ASD imprinting during prenatal brain development (Forsberg et al., 2018; Kubota & Mochizuki, 2016). Another explanation may be related to mitochondrial genetic profiles, which are uniquely transmitted from mother to fetus, and might play a role in the development of ASD (Giulivi et al., 2010). Of note, because we identified psychiatric conditions based on medical claims records, only treated mental illness could be captured. Based on a previous report (Chang, 2007), women are more likely to seek treatment for mental illness than men in Taiwan. This does not indicate that measurement error among mothers of children with and without ASD would be greater than that among fathers. However, if the differential measurement error among mothers is greater than that among fathers, the findings indicating a higher magnitude of association among mothers than fathers would be biased. As such, the findings should be interpreted with caution. Further investigations to dissect the observed differences between maternal and paternal effects on ASD in offspring are warranted.

Our findings for a temporal relationship between parental psychiatric disorders and ASD in the offspring may facilitate efforts to disentangle genetic and environmental contributions. We found that the risk of parental adjustment disorders only increased after the child's birth. As such, it is likely that increased parental stress related to rearing children with ASD plays a role in the development of parental adjustment disorders. In contrast, our finding of an inverse association between parental substance use only after the child's birth and ASD diagnosis supports that parental behavior and mental health can change after the child's birth and/or after a child is diagnosed with ASD (Chao et al., 2018; Weiss et al., 2012). Further investigation is needed to confirm and expand on these findings.

The strengths of this study include the use of a nationwide representative sample with a large sample size and adjustment for numerous potential confounders including parental age, socioeconomic status, pregnancy complications, and so forth. Unlike most previous studies to investigate a cross-generational association, which were focused on one particular psychiatric disorder, this study simultaneously examined a range of diverse psychiatric disorders. In addition, the timing of the establishment of parental psychiatric diagnoses in reference to the child's birth and ASD diagnosis was examined in detail in the present study, while these elements have rarely been explored in previous studies.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. First, we did not assess the effect of psychotropic agents. However, one meta-analysis showed no significant heterogeneity between studies with and without adjustment for the use of antidepressants (Ayano et al., 2019). Second, although diagnoses of most major psychiatric disorders in the NHIRD have been validated (Wu et al., 2020), the diagnostic codes for adjustment disorders and substance use disorders may be less valid since the claims data related to those codes were mostly from patients treated in outpatient departments, and thus might be less reliable compared to those admitted to a psychiatric ward who then received a comprehensive assessment and observation. Third, biologic paternal relationships could not be completely confirmed. As such, it is likely that the observed associations might be underestimated.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study provides supportive evidence that several parental psychiatric disorders are associated with the diagnosis of ASD in the offspring. The overall magnitude of the associations was higher among mothers than fathers; and the associations by the timing of the child's birth and ASD diagnosis varied across different parental psychiatric disorders. Together, these findings provide indirect evidence that both genetics and environment may play a role in these observed cross-generational associations. Future studies are needed to disentangle the influence of genetic and environmental factors on such associations to determine effective strategies to prevent autism and other psychiatric disorders among parents and their offspring.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tsung-Chieh Yao and Hui-Ju Tsai contributed to the concept and design. All authors contributed to acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Yi-Ling Chien, Chi-Shin Wu, and Hui-Ju Tsai contributed to manuscript writing. Chi-Shin Wu and Yen-Chen Chang contributed to statistical analysis. Funding was obtained by Tsung-Chieh Yao and Hui-Ju Tsai. Yen-Chen Chang, Mei-Leng Cheong contributed to administrative, technical, or material support. The work was supervised by Tsung-Chieh Yao and Hui-Ju Tsai.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tami R. Bartell at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Stanley Manne Children's Research Institute for English editing. This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. The interpretation and conclusions contained in this article do not represent those of the Bureau of National Health Insurance or the Ministry of Health and Welfare. We thank the staff members in the Data Science Center of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, for their comprehensive management and maintenance of the data.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by grants from National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan (PI: Hui-Ju Tsai, PH-111-PP-08; Chi-Shin Wu, CG-110-GP-01), Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (PIs: Hui-Ju Tsai, MOST 107-2314-B-400-031-MY3; and Tsung-Chieh Yao, MOST 106-2314-B-182-051-MY3 and MOST 109-2314-B-182-042-MY3), Chang Gung Medical Foundation (PI: Tsung-Chieh Yao, CMRPG3F1711–3, CMRPG3F0361, CMRPG3J0121, and CMRPG3K1371).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Ministry of Health and Welfare. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the author(s) with the permission of Ministry of Health and Welfare.