Saying what we mean, meaning what we say: Managing miscommunication in archaeological prospection

Funding information: This study was funded by the Department of Anthropology, Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archaeology, University of Alberta.

Abstract

In North America, archaeological prospection has recently undergone a surge in popularity, resulting in higher visibility for both scientific and fringe narratives. This has been partially due to increasingly sensationalized media articles that promote the use of technology to locate overgrown and subsurface features in the landscape. The heightened profile of the field and increasingly sensitive contexts in which it is applied (e.g., locating potential unmarked graves) has expanded the discipline beyond its usual settings where typical archaeological prospection rhetoric and narratives are applied. In this paper, we explore how the presentation of archaeological prospection can impact descendant communities and their burial and cultural spaces. We identify rhetoric, discourse and narrative as key considerations that have resulted in the twisting of interpretations to support fringe narratives. We present two case studies: (1) denialism surrounding unmarked graves at former Indian Residential Schools and (2) the reinterpretation of Indigenous spaces by Graham Hancock's Ancient Apocalypse. We draw upon these seemingly disparate examples as evidence that ambiguity in scholarly communication and ‘certainty’ in fringe communication can both be used to the detriment of Indigenous and other descendant communities in various ways that we term pseudoarchaeological colonialism. Finally, we recommend strategies on how to disseminate results in non-harmful ways and confront the wrongful usage of archaeological prospection.

1 INTRODUCTION

As archaeological prospection 1 standards are developed (e.g., Schmidt et al., 2015), ethics are discussed (e.g., Davis & Sanger, 2021; Sanger & Barnett, 2021; Wadsworth, Supernant, Dersch, & The Chipewyan Prairie First Nation, 2021) and reviews are conducted (Luo et al., 2019; Opitz & Herrmann, 2018), it is becoming increasingly clear that archaeological prospection methodologies need to be applied critically. This is especially true in North America where such work is increasingly prioritizing the needs of Indigenous and descendant communities, requiring changes to all stages of the research process. Although North America has seen excellent work and training in archaeological prospection (e.g., Conyers, 2013; De Vore et al., 2018; Kvamme, 2003), adoption of these techniques among archaeologists has been gradual compared to regions like Europe. In this paper, our focus is less on differences in physical collection strategies or analysis/interpretive techniques used in archaeological prospection; rather, we are interested in the very recent and heightened visibility of these technologies in the public. This increased visibility has impacted how archaeological prospection is perceived and how misinformation involving prospection has impacted the burial and cultural landscapes of modern Indigenous communities in North America. Although our examples are narrowly focused, the problems and strategies discussed in this paper are applicable for all regions.

The surge in the visibility of archaeological prospection in North America is reflected by the media firestorm surrounding ground-penetrating radar (GPR) discoveries of potential unmarked graves of Indigenous children at government-sanctioned residential and boarding schools in Canada and the United States (Montgomery & Supernant, 2022; Supernant, 2018). As a testament to the wide impact of this use of archaeological prospection, the Canadian Press named the 2021 GPR discovery of unmarked graves at a former residential school as Canada's ‘news story of the year’ (Meissner, 2021). In response, archaeological prospection in North America is rapidly changing and is being adopted by more people than ever before, including Indigenous nations.

An unintended consequence of increased public attention, however, is that these techniques, the researchers and their results are also being discussed, scrutinized or otherwise misused by fringe communities 2 and co-opted to support narratives of misinformation 3 and disinformation. 4 Archaeologists have long been aware of unintended impacts of public presentations. Leone et al. (1987, p. 283) noted that ‘archaeological interpretations presented to the public may acquire a meaning unintended by the archaeologist and not to be found in the data’ and invited scholars to critically reflect on and anticipate such impacts. Critical analysis helps archaeologists understand why, when different presentations of the same data are examined, we see discrepancies between the language and narrative used by archaeologists, the media and the public that may change the meanings of the data. This landscape is more difficult to navigate with the rise of fringe ‘experts’ that intentionally seek to undermine archaeological expertise and use archaeological prospection techniques to promote what are ultimately harmful narratives.

In this paper, we reaffirm that the establishment of a core of general ethics is important to develop for archaeological prospection but expand this discussion to the ethical presentation of data by researchers and its relevance to descendant communities. Drawing upon linguistic anthropological concepts of rhetoric, discourse and narrative, we present two distinct case studies that are impacting Indigenous burial/cultural spaces: (1) Indian Residential School (IRS) denialism and (2) the Netflix series Ancient Apocalypse (AA). In doing so, we highlight common themes and dangers of research co-option/manipulation and conclude with recommended communication strategies for archaeologists to manage these interactions. We recognize that we cannot always prevent the misuse of our work. Instead, we suggest that being prepared for co-option, especially when it concerns Indigenous communities and their burial grounds, helps archaeologists improve our communication methods and better manage co-option when it occurs. We encourage all archaeologists to consider our suggestions when presenting data to the public.

2 ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROSPECTION ETHICS WITH DESCENDANT COMMUNITIES

Reviews of archaeological prospection continue to focus on the technological advancements within the field (e.g., Luo et al., 2019); however, consideration of ethics is becoming increasingly relevant within the scholarly literature. There have been recent special issues in Archaeological Prospection and Advances in Archaeological Practice (Davis & Sanger, 2021; Sanger & Barnett, 2021), which contained several papers discussing the field and its ethical impacts. From this and other recent research, it is clear that although no universal ethical code exists, many practitioners of archaeological prospection share similar concerns regarding the changing field. These include the impact of archaeological prospection on living communities (Cohen et al., 2020; Parcak, 2009), the potential de-skilling of users within the field (Kvamme, 2018; Opitz & Herrmann, 2018, pp. 12–13; Trinks et al., 2018, pp. 30–31), and the lack of consistent regulations for geophysics and remote sensing applications compared to archaeological projects involving ground disturbance (Davis et al., 2021; Wadsworth, 2020). While these (and many other ethical considerations) have relevance for work with Indigenous and descendant communities, their impacts have only recently begun to be discussed (Davis et al., 2021; Nelson, 2021; Sanger & Barnett, 2021; Wadsworth, Supernant, & Kravchinsky, 2021).

Archaeology has been an extractive and colonial practice that has impacted Indigenous and descendant communities in negative ways (e.g., grave robbing, burial ground desecration and erasing their histories; Deloria, 1969; Tuhiwai-Smith, 2012). Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, Indigenous critiques of archaeology were published (e.g., Deloria, 1969); however, these were not reflected in archaeological literature until the 1990s (e.g., Nicholas & Andrews, 1997). This timing is in part due to legal decisions that led to changes to archaeological practice (e.g., Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act [NAGPRA] and the Delgamuukw decision) and led to many becoming more educated around Indigenous issues (Colwell-Chanthaphonh et al., 2010; Martindale, 2014). Subsequently, several professional North American organizations have revised their ethical codes (e.g., Society for American Archaeology and the Canadian Archaeological Association [CAA]) to better recognize the responsibility of archaeologists to work with Indigenous and descendant communities; however, these have not considered archaeological prospection specifically. Generally, these techniques are assumed to be a positive aspect of working with Indigenous communities, as they are less invasive (Gonzalez et al., 2006; Wadsworth, Supernant, Dersch, & The Chipewyan Prairie First Nation, 2021), although it is not quite as simple as that (e.g., Davis & Sanger, 2021; Glencross et al., 2017; Nelson, 2021; Sanger & Barnett, 2021; Wadsworth, 2020; Wadsworth, Supernant, Dersch, & The Chipewyan Prairie First Nation, 2021), and incorporating ethical practices within archaeological prospection requires reframing theory, methodology and the methods themselves.

Archaeological prospection techniques disturb the ground less than traditional excavations. They are typically faster and provide more coverage than standard archaeological methods, making them ideal for burial ground and sacred space investigations with Indigenous communities. Even with good intentions, however, geophysical and remote sensing techniques can also promote negative and unethical behaviour. These techniques can exacerbate ‘fly-in/fly-out’ research, circumventing community relationship building (Wadsworth, Supernant, Dersch, & The Chipewyan Prairie First Nation, 2021). Differential access to expensive techniques could also create new divisions between communities (Sanger & Barnett, 2021). Finally, archaeological prospection creates datasets that are readily shared and highly valued but easily misunderstood due to levels of ambiguity brought on by expert jargon and the nature of data interpretation. These new digital datasets can play on cultural differences and damage relationships (for an example, see Sanger & Barnett, 2021, p. 197). In the next section, we examine one ethical consideration under the microscope: the presentation of archaeological prospection results.

3 THE PRESENTATION OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROSPECTION DATA

Here, we use linguistic anthropological concepts of rhetoric, discourse and narrative as useful analytical tools to examine how and why archaeological prospection studies can be co-opted by fringe discussions.

Narratives are types of stories that contain information about past events/experiences and their sequence (Palmer, 2005). They often contain relational links that convey senses of ourselves, places, histories, knowledge and objects (Linde, 1993). For these stories to be interpreted, they must be spoken, uttered or otherwise shared using rhetoric. Although there is an inherent link between rhetoric (the words we use) and narrative (the stories we tell), there is considerable interpretive space between these two concepts where knowledge is transmitted between two subjects, known as discourse (Sherzer, 1987). Discourse is where rhetoric and narratives are culturally encoded and referentially understood by the receiving person (Sherzer, 1987). Discourse is also where language/communication creates certain groups of people who understand the communication and alienates (either intentionally or unintentionally) those who do not (Foucault, 1972; Linde, 1993). For example, medical doctors communicate through a discourse of medicine, which has a specific language and cultural context that can be misunderstood by outsiders (Foucault, 1972, pp. 52–55).

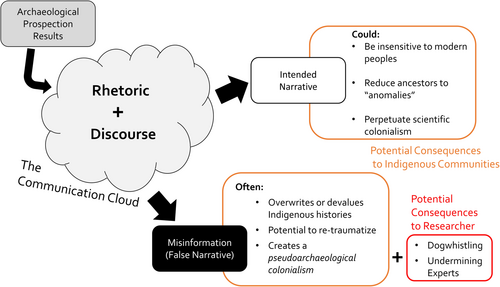

When groups are excluded from discourse, it can lead to misinterpretation and data could be used for the promotion of misinformation and disinformation (Figure 1). Below, we highlight how archaeological prospection narrative and rhetoric can be understood through different discourses (i.e., academic vs. stigmatized knowledge) and potentially be misused.

3.1 Narrative—The stories we tell

Prior to starting a study, researchers are already forming questions that conform to certain narratives. In North America, most archaeological prospection studies remain discovery narratives, which position western scientists as being the first to uncover places. For example, a study might be using a particular technique to investigate a previously un-surveyed location or to locate archaeological materials previously unknown to western scientists. Another narrative is a confirmation/rejection narrative where scientists seek to confirm or refute previous hypotheses. There is nothing inherently wrong with these narratives; however, they can promote erasure of previous histories and be seen to invalidate other forms of knowledge. It is important to note that we do not suggest that the scientific method (reproduceable hypothesis formation) is a matter of narrative, rather, in our analysis here we separate the intention/question from the method/data.

Equally harmful is when archaeological prospection rhetoric and discourse are used in ways that create new, unintended and even false narratives (Figure 1). Not only does this de-value experts but it can also cause a host of problems for Indigenous communities who have their own narratives of the landscape. The dissonance between the community narrative and the ‘accepted’/public narrative (at best) can cause distress and devaluation of Indigenous histories. At worst, it can create a pseudoarchaeological colonialism, where wrongful and fringe ideas replace both Indigenous and western scientific narratives.

Narrative is the most obvious component with which most people are concerned. The ways we create narrative (rhetoric and discourse), however, are generally less considered but equally impactful in communication.

3.2 Rhetoric—The words we use

Non-specific vocabulary has been an issue in archaeological prospection for years. One of the most problematic words commonly employed across archaeological prospection is anomaly. In his research on GPR, Conyers (2013, p. 150, emphasis in original) discussed the term as follows:

Almost all GPR reflection profiles are filled with ‘anomalies’, as those are nothing but reflections created by a change in wave velocity along buried interfaces …

… I therefore recommend not applying the word anomaly to a GPR data set except in certain specific ways (when there really is something that is very different from what can be seen in a survey).

We agree that only when absolutely necessary should non-specific words, like anomaly, be used to describe features; instead, preference should be given to their geophysical or geometric traits, environmental parameters and archaeological context (Conyers, 2012, pp. 29–30; 2013, pp. 149–150). Although words like anomaly are now considered old-fashioned (Conyers, 2013, p. 150), many prospection results are still reported this way. In our experience, Indigenous communities are concerned about the use of anomaly when using geophysical techniques to locate potential graves of their relatives and it also creates opportunities for those seeking to cast doubt on prospection results.

Similarly, overly complex vocabulary is a barrier to comprehension outside of academic discourse (Kerwer et al., 2021). Archaeological prospection is rife with overly complex vernacular that many people skim-read. However, these overly complex words are often where we attempt to communicate our interpretations and confidence in the findings. These issues contribute to the challenge of effectively presenting data observations and interpretations using scientific vocabulary, which can lead to potential misinterpretations. Identifying more accessible alternatives for these complex terms is beyond the scope of this paper.

3.3 Discourse—The connection between rhetoric and narrative

Archaeological prospection discourse is not easily understandable to the public, as it sits at the intersection of several specialized fields of study. Often, non-academic readers understand our results within their own discourses, distilling the most readily understandable or concrete concepts. Similarly, scientific phrasing used to hedge interpretations based on expert confidence can be skewed towards either the definitive or the inconclusive (e.g., ‘potential burial features’ become either graves or nothing).

While some misconceptions seem innocuous, they become potentially harmful when viewed from within a conspiratorial stigmatized knowledge discourse. Described by political scientist Michael Barkun, stigmatized knowledge refers to ‘knowledge claims that have been ignored or rejected by those institutions [e.g., universities, scientific communities, government agencies] we rely upon to validate such claims’ (Barkun, 2015, p. 115), but which are regarded by the claimants as being true despite institutional rejection (Barkun, 2013, p. 26). Barkun (2013, pp. 26–27) identified five types of stigmatized knowledge claims: forgotten, superseded, ignored, rejected and suppressed.

In stigmatized knowledge claims, the stigmatization is viewed as evidence of truthfulness (e.g., something must be true because it is being suppressed, rejected, ignored, etc.). This focus on stigmatization as a signifier of truthfulness, rather than factual evidence, also means that believers in one claim of stigmatized knowledge are likely to believe or be sympathetic to other claims (Barkun, 2013, 2015). For example, someone who believes pseudoarchaeological theories about Atlantis may also believe claims of UFO sightings simply because both have been stigmatized by knowledge validators. The lack of institutional validation of knowledge claims helps create a community of individuals that separates themselves from ‘mainstream science’ (Barkun, 2013; Foucault, 1972).

When archaeological prospection results are viewed within a discourse of stigmatized knowledge, facts cease to matter, and the perceived stigmatization becomes evidence of truth. The public will take their own understandings of our words and create their own narratives of our research. Sometimes, this results in the undermining of expert authority (‘The geophysics results are a hoax!’), promotion of their own experts (‘here is a real scientist working to find the truth’) and conspiratorial thinking (‘Archaeologists are hiding the truth!’). To explore how archaeological prospection results are interpreted within stigmatized knowledge discourses, we selected two case studies from different contexts to demonstrate how archaeological prospection rhetoric and narrative are being called into question or misused by fringe groups in similar ways that are harmful to a broad range of Indigenous sites.

4 CASE STUDIES

4.1 Case Study 1: IRS denialism

Our first case study stems from our work supporting Indigenous communities in Canada using archaeological prospection techniques to locate potential unmarked graves of children who died at government-sponsored, church-run IRS (Truth and Reconciliation Commission [TRC], 2015). These institutions were part of a government programme that took Indigenous children away from their families and communities to assimilate them into Canadian society. Over 150 000 children were taken, and thousands of children died at these institutions from a combination of abuse, disease, neglect, lack of medical care and malnutrition. Many families whose children died were never notified of their child's death or their burial place.

Canada has been investigating the residential schools since the mid-1990s, which resulted in the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement and the formation of a TRC in 2006. The TRC's mandate was to witness the testimony of survivors and document the abuses that occurred at these institutions. During the TRC, many survivors brought up the missing children, and while not originally part of their mandate, the stories were so common that the final report included an entire chapter dedicated to finding the missing children (TRC, 2015, Chapter 4). A public apology for the residential school system was given by the former Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper (Government of Canada, 2008), and in 2022, the system was recognized as genocide by the federal government (Olarewaju, 2023).

Over the past 15 years, some Indigenous communities have been searching for missing children, but it was not until the news of potential unmarked graves being located using GPR near the Kamloops Indian Residential School was announced in May 2021 that international attention spotlighted the issue (Sterritt, 2021). Journalists across the globe reported on the story, the Canadian flag was lowered to half-mast for months and funding for communities to find their children was announced (Government of Canada, 2022). Non-Indigenous Canadians expressed horror and shock at hearing about these potential graves and memorials sprung up around the country to remember the children. In many of these cases, the number 215 was used, although it is not actually tied to the number of children (or even reflections) that were located with GPR. The number 215 resonated strongly, and it was not long before numbers of children's graves circulating on social media began to climb.

The initial rush of reporting used terms and language that misrepresented the GPR results, including the use of mass grave and reporting that the ‘remains’ of 215 children had been found. Media and other sources overstating the geophysical results were at the core of a lot of misunderstanding, leading to impressions that GPR operated like an X-ray and could locate skeletons of children in graves. These misconceptions, now common in Indigenous communities with whom we work, make it harder for experts to explain the real possibilities/limitations of geophysical techniques. The media reports also gave the impression that these potential burials were of children who had been murdered, while the reasons for their deaths are multifaceted. With every media release, the number of how many ‘graves’ were found took centre stage, but the language around the results changed due to the ongoing education of the Canadian public in GPR (Table 1).

| Date of news release | First Nation (school name) | Release language (no. found) |

|---|---|---|

| 27 May 2021 |

Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation (Kamloops Indian Residential School) |

Unmarked graves (215), mass grave; later revised (200 with no mass grave) |

| 1 June 2021 |

Muskowekwan First Nation (Muscowequan Indian Residential School) |

Unmarked graves (35) |

| 14 June 2021 |

Sioux Valley First Nation (Brandon Indian Residential School) |

Potential graves (104) |

| 23 June 2021 |

Cowessess First Nation (Marieval Indian Residential School) |

Unmarked graves (751) |

| 30 June 2021 |

Lower Kootenay Band (St. Eugene's Mission School) |

Human remains in unmarked graves (182) |

| 13 June 2021 |

Penelakut Tribe (Kuper Island Industrial School site) |

Unmarked graves (>160) |

| 4 August 2021 |

Sipekne'katik First Nation (Shubenacadie Indian Residential School) |

Unmarked graves (0) |

| 25 January 2022 |

Williams Lake First Nation (St. Joseph's Mission Residential School) |

Potential burial sites (93) |

| 15 February 2022 |

Keeseekoose First Nation (St. Philip's and Fort Pelly Indian Residential Schools) |

Ground disturbances believed to be graves (54) |

| 1 March 2022 |

Kapawe'no First Nation (Grouard/St. Bernard's Indian Residential School) |

Potential graves (169) |

| Summer/fall 2022: Search updates, interlocutor announced, national gatherings, Pope visit. Few releases as work continued | ||

| 12 January 2023 |

Starblanket Cree Nation (Qu'Appelle Indian Residential School) |

Anomalies/‘hits’ (>2000) |

| 23 January 2023 |

Wauzhushk Onigum Nation (St. Mary's/Kenora Indian Residential School) |

Plausible burials (171) |

| 25 January 2023 |

Williams Lake First Nation (St. Joseph's Mission Residential School) |

Additional: Possible burial sites (66) |

- Note: This table is not an exhaustive list but only those that released a media statement and explicitly noted results of archaeological prospection surveys.

The widespread use of initial and enduring misconceptions led to almost immediate backlash in various circles, including those who used the misconceptions to support and spread denialist misinformation and disinformation about the IRS system. Heath Justice and Carleton (2021, n.p.) define residential school denialism as ‘not the outright denial of the Indian Residential School (IRS) system's existence, but rather the rejection or misrepresentation of basic facts about residential schooling to undermine truth and reconciliation efforts’. Quoting French anthropologist Didier Fassin, Jones (2021, p. 104) also noted that denialism is ‘an ideological position whereby one systematically reacts by refusing reality and truth’.

Discussing the denialism of Indigenous history and the Stolen Generations in Australia (a colonial project very similar to the Canadian IRS), Jones (2021, p. 113) observed common themes of denialist tactics like what we have observed in IRS denialism in Canada, including debates over phrasing, the insistence on hearing multiple perspectives of events and the ‘cross-pollination of ideas where downplayers act as enablers for deniers’. Responding to the GPR results from Kamloops, denialist narratives used various rhetorical strategies designed to distort facts, cast doubt and present alternative narratives. Denialist narratives focused on the terms used by the media such as mass versus individual graves, despite the quick correction of that language in most news outlets (Table 1). Targeting the GPR results, rhetorical strategies also repeatedly emphasized that ‘not one body has been found’, to try to undermine the thousands of archival documents that record the deaths of children. Demands for excavations and exhumations were also used to convince denialist audiences that without physical bodies, the GPR results should be considered a hoax. Additional rhetorical strategies focused on emphasizing that unmarked graves located in school cemeteries should not be surprising, as one would expect to find graves within a cemetery. These comments, however, served to distract their audience from the fact that no school should have a cemetery.

In light of the GPR results from Kamloops Indian Residential School, residential school denialist articles appeared in major Canadian media outlets (e.g., The Globe and Mail) and on extreme far-right websites (e.g., American Renaissance). 5 Websites specifically devoted to residential school denialism and the undermining of the expertise of communities, archaeologists and geophysics practitioners involved in the location of unmarked graves at residential schools also appeared. For example, the Indian Residential School Records Website (IRSW) was created by Nina Green, an independent researcher and writer for The Dorchester Review (Pew et al., 2022; Rubenstein, 2023), to question what was deemed to be only ‘limited perspectives’ on the experiences at residential schools and to cast doubt upon the Kamloops GPR results and undermine the expertise of involved archaeologists (IRSW, 2022a, n.p.; 2022b). Similarly, the Indian Residential Schools Research Group (IRSRG) website was organized by a collective of individuals in 2022 and is comprised of numerous denialist articles and videos (IRSRG, 2022).

Residential school denialist videos were also created in response to the unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. One of the first major denialist videos was a documentary-style film titled ‘The Canadian Mass Grave Hoax’, created by the Canadian far-right website The Counter Signal and published on the YouTube channel belonging to Lauren Southern, one of the film's co-hosts and producers (and formerly of The Rebel [Langlois et al., 2021, p. 752; Perry & Scrivens, 2019, p. 37]). Released on 19 September 2021, ‘The Canadian Mass Grave Hoax’ was framed as an investigative response to the burning of several churches across Canada in the summer of 2021. The film, which at one point featured video footage of two of the authors of this paper used without their knowledge, sought to cast doubt on the reports from the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The film, which has since been deleted from The Counter Signal's website but remains available on Southern's YouTube channel, was described as being concerned about the perceived framing by the media of ‘this destruction and terrorist [sic] as a type of atonement—a punishment for deserving Christian congregations that are supposedly the perpetrators of genocide’, which it claimed was ‘a big lie’ that had been ‘repeated by so many in positions of public trust, that observers are unable to tell truth from fiction anymore’ (The Counter Signal, 2021a, n.p.). The film's producers, Southern and Keean Bexte, a former Rebel journalist and founder of The Counter Signal, repeatedly pointed out contradictions between the media's reports (e.g., mass graves) and the official reports from Tk'emlúps Nation and archaeologists (e.g., individual graves) as being suspicious. Bexte and Southern claimed that the lack of access granted to them for interviews with Tk'emlúps representatives indicated that Tk'emlúps supported the media's intentional portrayal of Christian Canadians as the perpetrators of genocide.

The creators' lack of access to the Kamloops Indian Residential School grounds was also viewed as hiding the truth about what had actually been uncovered by GPR. To prove this, Bexte and Southern stood outside the property's fence and flew a drone over top of the property, recording a video of numerous marker flags in the ground. Deciding to learn more about GPR, Southern and Bexte then discussed a 2009 paper about the effectiveness of using GPR to locate unmarked graves in cemeteries (Fiedler et al., 2009). Bexte read portions of the abstract, which included (among others) the phrase, ‘the interpretation of GPR profiles is nevertheless difficult and often leads to incorrect results’ (Fiedler et al., 2009, p. 385). Bexte concluded for the audience, ‘the point here is that you can't just rely on a couple squiggly lines to condemn a nation of genocide’ (The Counter Signal, 2021b, n.p.). Further reading of both the abstract and the article beyond the quotes Bexte read, however, would have shown that Fiedler et al.'s (2009) study concluded that GPR surveys were, indeed, very useful tools for identifying unmarked graves.

Similar to what Jones (2021) noted in Australia, ‘The Canadian Mass Grave Hoax’ acted as a junction point where downplaying the truths of what happened at residential schools enabled outright denialism of truths. 6 The film acknowledged that ‘horrific things occurred at residential schools’ (The Counter Signal, 2021b, n.p.); however, they exploited the ambiguity inherent to GPR survey results to downplay the experiences and testimonies of survivors, which enabled the film's final denialist conclusion that ‘absolutely none of this narrative is supported by fact’ (The Counter Signal, 2021b). Furthermore, the film's producers also created a connection to far-right media spaces, where denialism was amplified to extreme and dangerous levels.

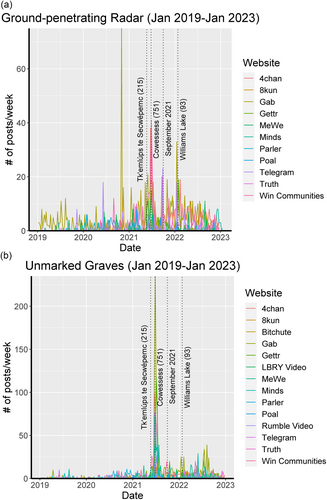

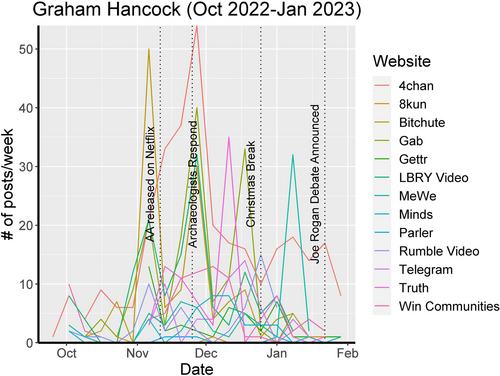

To assess how these denialist narratives were being taken up by fringe communities on a larger scale, we used the Social Media Analysis Toolkit (SMAT, https://www.smat-app.com/) to assess social media post frequency connected to the release of GPR survey results in the mainstream media. The SMAT was developed to ‘help facilitate activists, journalists, researchers and other social good organizations to analyse and visualize harmful online trends such as hate, misinformation and disinformation online’ and searches through fringe internet forums for posts containing certain keywords. A simple R script was written to collate the different website's data into simple line graphs (Figure 2). We included posts (but not comments) on Gab, Parler, 4chan, 8kun, Win Communities, Poal, Telegram, Gettr, Rumble Video, BitChute Video, LBRY Video, RUTUBE Video, MeWe, WiMKiN, Minds and Truth Social in our analysis as these were the main websites that SMAT searches. We decided to exclude TikTok (because of the popularity of the website for non-fringe uses) and VK (because it was restricted temporally) from this experiment. If a website included less than five mentions of our search word (given date parameters), it was not included in the plots. Large spikes observed were manually checked to assess whether they related to the spreading of IRS denialism. When appropriate, we annotate the graphs with key events.

We found that when key stories were released concerning GPR searches for unmarked graves at former IRS, a subsequent flurry of posts could be seen in fringe online spaces (Figure 2). For example, Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation's release of their findings in late May 2021 resulted in a large and sustained spike in online forums the following month. This was echoed or exacerbated by subsequent findings (Cowessess First Nation, 25 June 2021; see Table 1 for additional examples) and notable anniversaries/national days (e.g., National Day for Truth and Reconciliation—annually on 30 September). We also noted that technology-related references (i.e., GPR) were less frequent than the context or results-related discussion (i.e., unmarked graves) but exhibited the same trends.

Surveys for unmarked graves at former IRS represent a relatively unremarkable target for archaeological prospection, applied in the most sensitive of contexts. Although there is great variation in geophysical experience across Canadian archaeology (resulting in different methods/results), we found that this has little to do with the resulting narratives that are spread. Instead, how the scientific results were communicated (rhetoric/narrative), determined how they were understood and transformed by the media and then later by the denialists. When we examined IRS denialist posts, we saw that they were constructed around the rhetoric reported by survey results in the media (not by the practitioner). Survey results were reinterpreted and placed into the domain of stigmatized knowledge, where the readers of these articles perceived themselves to be the victims of narratives created by a perceived suppression of residential school truths by communities, the media and archaeologists. These deliberately misleading and harmful narratives sometimes became energized into threats of real harm to both residential school locations and to people, especially through dog whistling. Dog whistling is a rhetorical strategy referring to the sharing of coded messages or signals designed to be understandable to only the target audience (Political Dictionary, 2022). For example, an early 2022 article written about the Kamloops Indian Residential School on the virulent white nationalist website American Renaissance labelled the results of the GPR survey as a ‘hate hoax’ against white people, placed the leading archaeologist as the starting point of this hoax and shared a direct link to the archaeologist's university contact information. Pairing the identification of the archaeologist as a perceived threat with the sharing of contact information was a subtle dog whistle to the readers of the article to contact the archaeologist directly. 7

4.2 Case Study 2: Pseudoarchaeological prospection at Indigenous cultural sites

In western culture, burial spaces are often separated from cultural sites requiring different investigative protocols. This distinction is not always as clear for Indigenous spaces, where cultural sites and burial spaces are often intermixed and part of the same landscapes. Therefore, threats to archaeological sites can also be threats to burial and other sensitive spaces. As a result, the potential of harm from the wrongful use of archaeological prospection is not always as overt as presented in residential school denialist articles and videos. Sometimes, harm is shrouded by the label of ‘entertainment’ in popular shows and books, whereby Indigenous history and cultural sites are attributed to lost civilizations like Atlantis or even extraterrestrials rather than Indigenous peoples.

For our second case study, we examined the use of archaeological prospection to support conspiratorial ideas and denounce experts in a popular Netflix documentary series, AA, presented by Graham Hancock. The self-described purpose of AA was to ‘overthrow the paradigm of prehistory’ (Tiley, 2022a, n.p.), and we note similarities between the show and the denialist examples above in the ways they both cast doubt upon expertise in order to promote alternative narratives about human history. Hancock is a self-described investigative journalist who promotes the unsupported Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis, for which he has been searching ‘for a lost civilization of remote prehistory—an advanced civilization utterly destroyed at the end of the Ice Age and somewhat akin to fabled Atlantis’ (Hancock, 2019, p. xiv). Over the course of his career, Hancock has made repeated stigmatized knowledge claims that humans have forgotten about an advanced Ice Age civilization and has proposed fringe interpretations of many cultural heritage sites.

Archaeological prospection, such as GPR and drone imagery, was included in various episodes of AA. In the premiere episode, for example, Hancock visited Gunung Padang on the island of Java, where they described their fringe theories and showed geophysical data as ‘conclusive evidence’. Interpretations of geophysical data were left under-explained and used to lend legitimacy to Hancock's theories of a lost ancient civilization. These vague descriptions and over-extrapolated interpretations were partnered with claims of stigmatization (e.g., ‘This is an idea that mainstream archaeology finds very hard to accept’) that acted as a substitute for the lack of conclusive archaeological evidence. It did not matter that Hancock did not have factual evidence because the stigmatization was the evidence. Through partnering stigmatization with archaeological prospection techniques, Hancock simply needed to cast enough doubt on archaeologists that his audience could believe that archaeologists were suppressing truths.

As the series episodes continued, Hancock turned his sights to Indigenous sites in North America (Tiley, 2022b), where the above themes and their threats to Indigenous cultural/burial spaces were continued. It was Graham Hancock's stigmatized knowledge claims on-screen during Episode 6 that led to off-screen harassment of archaeologists, energizing of far-right media and figures, and a doubling-down of the reattribution of Indigenous sites in North America to an invented history.

In Episode 6, Hancock visited several Indigenous mound sites in the United States, with significant attention given to the Giant Serpent Mound National Historic Landmark in Ohio. Hancock reattributed the original construction of large mound structures to the lost civilization he was searching for, stating that ‘the few [mound] sites that survive may be critical in establishing the possibility of a lost civilization’ (Tiley, 2022b, n.p.). Hancock's theory that Indigenous mound sites were initially constructed by a lost civilization and re-used by later Indigenous people is akin to an updated version of ‘mound-builder myths’ (Feder, 2019, p. 160). Since the beginning of settler colonization of the Americas, mound-builder myths have proposed that Indigenous mound structures were constructed by a variety of suggested pre-Indigenous cultures, including Atlanteans, the Lost Tribes of Israel and a generic lost white race (Colavito, 2020). Mound-builder myths were even cited by former American president Andrew Jackson in his justification for the Indian Removal Act (Colavito, 2020, pp. 113–122).

After arriving at the Giant Serpent Mound National Historic Landmark, Hancock shared that, after making several attempts, his production team had been denied permission to film at the site by the site's managers, the Ohio History Connection (OHC). Hancock then read from the OHC email, ‘our role is to ensure that Serpent Mound's integrity and preservation both physically and its historical interpretation are maintained. Because the presenter of this series, Graham Hancock, proposes a theory and story that do not align with what we know to be true, your request is declined’ (Tiley, 2022b, n.p.). Following this, Hancock asserted that ‘the correct word for this so-called mission to protect the interpretation of the site is, of course, censorship. And what more effective way for archaeologists to censor, and retrain, and crush opposing views than to deny access to archaeological sites’ and that censorship of alternative ideas was ‘systematic and consistent behaviour among archaeologists’ (Tiley, 2022b, n.p.).

Despite the denial of permission to film at Serpent Mound, the episode then featured drone footage and interpreted 3D models of the site. Hancock met with Jeffrey Wilson, who owns the property neighbouring Serpent Mound and is the president of the Friends of Serpent Mound (FOSM), a volunteer organization dedicated to ‘caring for ancient sites’ (FOSM, 2021). Hancock and Wilson's discussions about their archaeoastronomy theories about the site and the dismissal of those theories by archaeologists were paired with several minutes of drone footage and digital ‘reconstructions’ of Serpent Mound. In a later interview, Wilson confirmed that some of the drone data shown were specifically collected for the Netflix series (The Strange Road, 2022).

AA's use of drones in this episode echoes the use of drones in ‘The Canadian Mass Grave Hoax’ and highlights a crucial issue that continues to arise in archaeological prospection. Davis et al. (2021, p. 305) recognized that ‘knowledge produced by remote sensing instruments is often viewed as fundamentally different from other sources of archaeological and anthropological data’ and this kind of data is assumed by archaeologists to be less harmful. They go on to describe how laws regulating drone flights are often unrelated to heritage/privacy legislation and ambiguous concerning the data the drones collect (Davis et al., 2021). Gupta et al. (2020) specifically discussed how digital data produced from archaeology and remote sensing surveys can also be utilized without proper consultation with First Nations communities. The case studies' use of drone data is a clear example of how archaeological prospection can circumvent the efforts of archaeologists and heritage management organizations to curtail potentially harmful narratives being shared about Indigenous sites.

5 FROM DENIALISM TO ANCIENT APOCALYPSE

Though connections between a Netflix show and IRS denialism may not be immediately apparent, when we compared each of the case studies using our framework, we realized they were remarkably similar in terms of narrative, rhetoric and discourse. Both seek to take advantage of an uninformed audience (e.g., Netflix viewers and the settler population in Canada), through using simple, jargon-free rhetoric to walk audiences through what appears to be a straightforward story. Both the IRS denialists and Hancock use or discuss archaeological prospection results to appear as scientific as possible, while also undermining the credibility of factual interpretations of the same data to prime the audience for their ‘fringe’ interpretations. Once the audience was primed, discussions were reframed within a stigmatized knowledge discourse. For Southern and Bexte, the Canadian state and Indigenous peoples are targeting white Christians. For Hancock, ‘Big Archaeology’ was censoring his beliefs and theories.

Indigenous scholarship can help us understand the impacts of these fringe narratives and what Zimmerman and Makes Strong Move (2008, p. 191) called an ‘intellectual landscape of clearance’. These authors specifically described how scientific archaeological narratives, when adopted en masse, can reclassify landscapes and sever connections between descendant communities and their landscapes (Zimmerman & Makes Strong Move, 2008). Zimmerman and Makes Strong Move (2008, p. 190) called this practice ‘scientific colonialism’ (see also Nicholas & Hollowell, 2016). We propose that both IRS denialists and AA (as well as other fringe groups) attempt a similar pseudoarchaeological colonialism of Indigenous burial spaces and landscapes, where they attempt to cast doubt upon Indigenous narratives and usurp typical scientific narratives within their fringe theories (e.g., Atlantis). To do this, archaeological prospection is mobilized as one of their tools. Once Indigenous nations no longer have control over the narrative, it becomes easier for governments, corporations and private groups to impose their colonial interests (Nicholas & Hollowell, 2016).

There are also considerable risks for researchers who work to confront fringe groups. These will be further explored below when we discuss the different responses to each of the case studies. Two unifying themes between the two case studies emerged: (1) researchers can be personally targeted by fringe groups and (2) archaeological prospection can often be employed in absentia of heritage laws and management officials.

6 STRATEGIES/RECOMMENDATIONS

Archaeological prospection faces the challenge of meaningfully communicating our work while finding ways to manage misinformation when it arises. Even in carefully shared studies, the possibility exists that results can be exploited or reinterpreted in ways the data do not support. In archaeological contexts, it is easier to disregard some misuses knowing that, if ever in doubt, ground-truthing could be done. There are many contexts, however, when ‘anomalies’ will not be tested against archaeological excavation (e.g., burial spaces). As has been shown in the case studies, a lack of archaeological ‘confirmation’ creates ambiguity that can be exploited to support the validity of fringe interpretations and/or deny the legitimacy of experts.

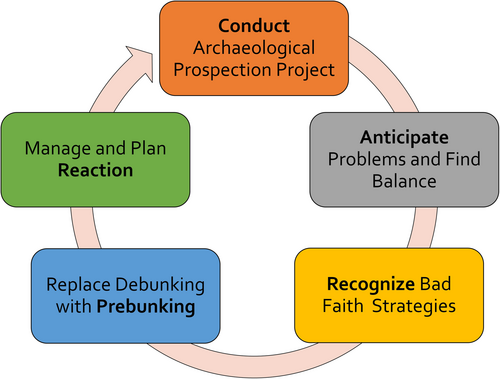

Misinformation and disinformation can have harmful consequences for individuals, communities and organizations and should be confronted. The struggle is in finding effective methods of confrontation. How do we approach this aspect of our research? Below, we present recommendations drawn from research and our experiences with conversing, confronting or otherwise thinking about issues surrounding public-facing archaeological prospection (Figure 3).

6.1 Anticipate problems and find balance

First, we recognize that there will always be bad actors who try to use the results of archaeological prospection in problematic ways. Being aware of how archaeological prospection could be used in fringe narratives allows practitioners to use narrative and rhetoric in publications that could minimize the amount of subsequent misinterpretation. Additionally, in highly sensitive contexts, such as the potential unmarked graves around IRS, we also have a responsibility to use thoughtful language that respects the fact that we may be finding the graves of loved ones from that community and the presentation of results can be traumatic.

- Be true to the results and careful in the language used for interpretation.

- Clearly define conditional language used to assess confidence (e.g., ‘potential’).

-

Respect other forms of knowledge:

- In Indigenous contexts, this can mean including qualifying statements that recognize and uphold Indigenous knowledge.

- This can also include recognizing multiple lines of evidence that increase confidence in the results of archaeological prospection.

- Recognize ambiguity while also acknowledging the scientific understanding of the various techniques used.

- Provide the collected data to the Nation so that they are able to seek second opinions.

6.2 Recognize bad faith strategies

- seek academic credibility for fringe interpretations/theories;

- undermine (actual) experts and published literature;

- justify how geophysics and other remote sensing techniques can circumvent or replace archaeological forms of validation; and

- revise history within stigmatized knowledge discourses and narratives, which were also connected with hate groups.

The recognition of these strategies not only allows researchers to avoid potentially damaging and/or traumatic narratives within our own communications but also allows us to plan how best to handle co-opted claims about our communicated results. Digital media folklorist Whitney Phillips's (2018) valuable document ‘The Oxygen of Amplification’ described how outrage is a desired response for fringe communities and individuals, as it contributes to an amplification of their messages. Phillips (2018, p. 4) described how publicly confronting bad faith actors in digital spaces increased the likelihood (1) that similar disinformation/harassment tactics will be used in the future, (2) that the original piece becomes more visible and more influential, (3) that other conversations are flattened or reduced, (4) that the consumer of the media becomes desensitized to the issue and (5) that the amplification lends credence to the false narratives. Recognizing how outrage is intentionally generated can help us recognize when to respond, how to respond and when critical ignorance (see Kozyreva et al., 2022) is the more appropriate response. Furthermore, recognition of bad faith strategies used is an important part of ‘pre-bunking’.

6.3 Replace debunking with pre-bunking

In response to co-options of archaeological data, archaeologists have typically turned to debunking (exposing false claims) as a management strategy. However, as Van der Linden et al. (2017, p. 1441) succinctly stated, ‘in the battle against misinformation, it is better to prevent than cure’. Research has shown that debunking can be ineffective at reducing misleading information and can also create a backfire effect in which recipients become more convinced of the misleading information and more likely to interact with it (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010, 2015; Zollo & Quattrociocchi, 2018). This is especially true in cases of stigmatized knowledge claims when stigmatization is viewed as evidence of truthfulness.

Instead of debunking, research has shown support for the efficacy of pre-bunking (Roozenbeek & Van der Linden, 2021). Drawing from inoculation theory, pre-bunking is a pre-emptive refutation of a particular argument to build the reader's psychological resistance to unwanted persuasion (Van der Linden et al., 2017). Studies have shown that prior exposure of readers to both facts about a certain idea and ‘red flags’ about ideas to be wary of, as well as sharing tools on how to critically evaluate content and identify misinformation, creates a greater resistance to misinformation (Cook et al., 2018; Van der Linden et al., 2017). In other words, knowing how to recognize misinformation weakens its ability to deceive.

We have provided a preliminary ‘red flag’ list in Table 2; however, these will be context specific. By better educating the public on the realities of archaeological prospection, we can hope that they will be less susceptible to influence by pseudoarchaeological misuses.

| Red flags | Examples |

|---|---|

| Too good to be true | Archaeological prospection is faster than regular archaeology but can be slow, complicated or otherwise expensive. Be wary of too good to be true project descriptions/quotes that claim to survey the following:

|

| Claims of human remains | Ground-based geophysical techniques do not find human remains. They sense the changes in physical properties that may (or may not) reflect past human activities (e.g., a burial). These must be interpreted by experts with experience. Current GPR technology/wide-scale collection strategies do not locate human bone |

| Extrapolating from incomplete data | Creation of elaborate models or conclusions without supporting evidence |

| Overstating results | |

| Clear holes in methodological research design |

- Abbreviation: GPR, ground-penetrating radar.

7 RESPONDING TO IRS DENIALISM AND ANCIENT APOCALYPSE

In many instances when our work is misused, our first reaction is to defend and debunk. It is important, however, to consider our methods of reaction, as to minimize the potential for harm to the communities we work with and to ourselves (e.g., receiving harassment and threats). After having shared research and experience-based communication strategies above, here, we evaluate two different communications responses to our two case studies and the subsequent outcomes.

Responding to the rise in media coverage around the use of archaeological prospection in detecting potential unmarked graves, the CAA formed the CAA Working Group on Unmarked Graves. This group brought together experts to combat misinformation about archaeological prospection techniques and collectively develop reliable, independent guidance for Indigenous communities. 8 Recognizing how confrontations may unintentionally strengthen fringe claims, the working group decided to avoid directly confronting denialist posts or articles and instead sought to share educational materials describing how archaeological prospection is used, how it works, its limitations and best practices/workflows for communities looking to conduct searches themselves (in other words, pre-bunking). Similar groups across fields were soon formed (e.g., Geophysics For Truth 9), and responses began to be coordinated. Additionally, one of the authors of this paper (Supernant) was featured in over 100 media interviews to spread this coordinated messaging.

Collective statements were also issued that confronted denialism as a whole, rather than individual denialists, and shared resources to help readers to recognize denialist rhetoric and narratives. 10 Following releases of collective resources and statements, there were some noticeable changes in the language surrounding unmarked grave discoveries in media reports and beyond (e.g., Table 1). In academic settings, talks supporting Indigenous communities searching for unmarked graves have shared collectively developed resources and pre-bunking information. As a result of these efforts, denialist narratives have not gained significant traction outside of a small denialist community, and the overwhelming media narrative in Canada remains one of support with Indigenous communities and their archaeological prospection studies.

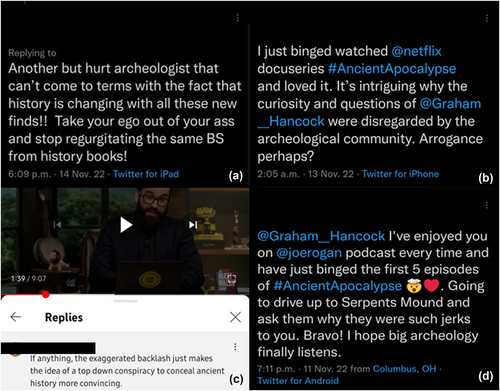

The archaeological response to AA was very different. Off-screen viewer reactions to AA became energized by both the claims of censorship in Episode 6 and archaeologists' general criticisms of the show. Within 1–2 weeks after its 11 November release, many archaeologists had shared criticisms in media articles, debunking threads on Twitter and direct social media comments to Hancock and his supporters that pointed out the numerous factual inaccuracies in the show and how Hancock's behaviour would violate archaeological codes of ethics. This included a statement issued by the Society of American Archaeology (2022). Hancock's supporters doubled-down on their support of the show in response to criticism, viewing criticism as proof of Hancock's claims of suppression and even suggesting visiting Serpent Mound to question the staff's decision to deny filming permission (Figure 4).

Dog whistling also became part of the reactions to archaeologist's criticisms. Hancock shared criticizing articles and threads on his social media accounts, often accompanied by amplifying statements of stigmatization that further energized his supporters. In response, Hancock's supporters flooded critics social media and emails with unsavoury replies. In December, Hancock shared an image of the email he received from OHC with the denial of filming permission, blocking his production team's contact information but leaving the OHC contact information unblocked. The FOSM (2021, n.p.) responded similarly on their website, linking the OHC's contact page to a comment reading, ‘If you watched the new Netflix Series “Ancient Apocalypse” and you are displeased with Graham Hancock not being allowed to film at the park. Then please, use the Ohio History Connection's contact us page’.

Suggestive of a backfire effect as described by Nyhan and Reifler (2010, 2015) and Zollo and Quattrociocchi (2018), Figure 5 illustrates a rise in posts about Hancock in online fringe communities following initial reactions from archaeologists. Furthermore, far-right figures and media drew attention to the claims of censorship in social media posts, videos and articles. As described by Phillips (2018), this was an example of giving ‘oxygen to amplification’, as it was the hope of these fringe groups that the continued reaction of archaeologists would fuel the ‘debate’ and spread their messages. We are not blaming or condemning archaeologists who publicly criticized AA, because we agree that criticism was necessary. However, we use Figure 5 as an example to point out that our well-intended actions can unintentionally draw negative consequences when we react without full consideration of our communication methods. For these reasons, we recommend that all archaeologists, beyond just archaeological prospection, review the communication strategies we have suggested in this paper and consider potential outcomes when engaging in public communications.

8 CONCLUSION

Archaeological prospection is an important tool for archaeologists to understand the past. The ambiguity inherent in these techniques and their difficult presentation, however, can lead to survey results being co-opted by fringe communities, where results are undermined and questioned (IRS denialism) or used to cast doubt on ‘mainstream’ archaeological interpretation (AA) to insert misinformation. In this paper, we discussed the impact of narrative, rhetoric and discourse used when engaging with archaeological prospection results and how the stories we tell, the words we use and in which contexts matter. This is especially apparent when engaging with sensitive surveys such as the use of GPR to detect potential unmarked graves of children who died at IRS, but it also applies to Indigenous cultural heritage generally. By illustrating how archaeological prospection was taken up to deny the presence of burials at IRS sites and how it was used to claim that archaeologists were covering up the ‘true’ (Atlantean) past of North America, we show how bad actors can twist our studies in ways that harm Indigenous communities as a form of pseudoarchaeological colonialism. To combat or minimize harm, we proposed a series of strategies for archaeologists to consider. Finally, we encourage all archaeologists to exercise great care when reporting on the results of their work and to learn how to recognize and combat the misuse of data. We must learn to say what we mean, mean what we say and counter the miscommunication and misrepresentation of archaeological prospection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our colleagues who helped inspire this paper, particularly the other members of the Canadian Archaeological Association Working Group on Unmarked Graves whose shared experiences in the search for the missing children have contributed to the formulation of this paper. Similarly, we would like to thank Dr. Andie Palmer, a generous mentor in linguistic anthropology. Finally, we would like to thank the Indigenous communities with whom we work because it is these partnerships and their hopes in archaeological prospection that greatly inspired and shaped this research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding this research.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The SMAT data used to support the qualitative interpretations in this study can be found by using the free online tool (https://www.smat-app.com/), or copies of the archived data and R scripts can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1 We use the term ‘archaeological prospection’ to encompass the application of a vast array of scientific prospecting techniques in archaeology (e.g., geophysics, remote sensing and geographic information systems).

- 2 ‘Fringe’ is used here to refer to views that branch away from the general consensus of a group (regardless of political alignment). In an archaeological context, fringe views encompass highly speculative alternative claims and theories and a general distrust of expertise.

- 3 False, misleading information shared without intent to deceive.

- 4 Same as the above but with intent to deceive.

- 5 To avoid driving further attention/‘clicks’ to these fringe sources, we have chosen to use web archive links (web.archive.org) to cite the archived sources without driving readership.

- 6 As of 1 May 2023, the video has almost 150 000 views.

- 7 In order to prevent driving readership to this website, citational information has been withheld and can be provided upon request.

- 8 Link to CAA Working Group on Unmarked Graves resources: https://canadianarchaeology.com/caa/resources-indigenous-communities-considering-investigating-unmarked-graves.

- 9 Link to Geophysics For Truth's website: https://www.queensu.ca/geophysics-for-truth/#:~:text=Geophysics%20For%20Truth%20is%20a,Indigenous%20Community's%20projects%20across%20Canada.

- 10 See the joint statement issued: https://canadianarchaeology.com/caa/news-announcements/joint-statement-indian-residential-school-denialism-caa-society-american.