Gastric anisakiasis suspected by point-of-care ultrasound finding in the emergency department

Abstract

Background

The diagnosis of gastric anisakiasis is typically confirmed by detecting larvae during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Therefore, it is important to raise clinical suspicion to prompt this procedure. While abdominal computed tomography is often performed for this purpose, the utility of ultrasound as a workup for gastric anisakiasis is not well established.

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old male with a past medical history significant for IgA vasculitis visited the emergency department with acute onset epigastric pain. The patient had sushi containing horse mackerel, mackerel, and sardines the night before admission. Point-of-care ultrasound revealed the thickened gastric wall, which enabled us to suspect gastric anisakiasis, prompting an emergent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. An emergency upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed the presence of three Anisakis larvae penetrating the gastric mucosa. Following treatment, his symptoms completely resolved.

Conclusion

This case suggests that point-of-care ultrasound can be a powerful diagnostic tool when clinicians suspect gastric anisakiasis.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric anisakiasis is characterized by severe epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting that frequently occur within hours of ingesting the causative fish and causes rarely critical allergic reactions.1 Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been more common in primary care settings. There are some reports that suggest the utility of POCUS for acute abdomen,2, 3 but the utility for gastric anisakiasis is unknown. We described a case of gastric anisakiasis in a 40-year-old male; POCUS played a crucial role in the rapid diagnosis.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 40-year-old male with a past medical history significant for IgA vasculitis visited the emergency department (ED) with the chief complaint of acute onset epigastric pain, which radiated to the right upper quadrant and right flank area. Further history was notable for having sushi with horse mackerel, mackerel, and sardines the night before the day of admission. The patient experienced gradual onset of epigastric pain approximately 12 h after consuming sushi, with the pain intensity ranging from 3 to 10 on the pain scale. The patient visited the ED about 24 h after eating sushi and reported no vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea.

On physical examination, the patient was not in acute distress, with the following vital signs: blood pressure, 128/94 mmHg; heart rate, 74 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18/min; oxygen saturation, 98% on room air; and body temperature, 36.7°C. The abdomen was flat and soft. There was tenderness in the epigastric area without rebound, guarding, or peritoneal sign. There was no costovertebral angle tenderness.

Laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 15,510/μL, a hemoglobin level of 14.5 g/dL, and a platelet count of 349,000/μL, aspartate aminotransferase of 18 U/L, alanine aminotransferase of 23 U/L, total bilirubin of 0.9 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase of 66 U/L, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase of 17 U/L, and amylase of 97 U/L.

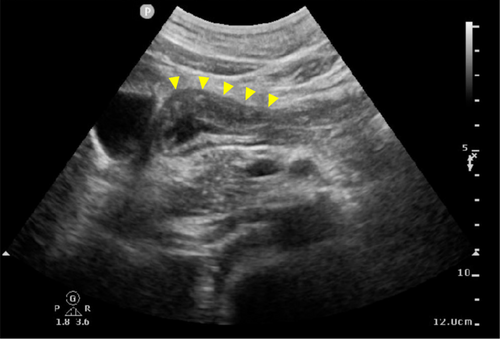

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) of the epigastric area was performed with the patient in a supine position, using a 1–5 MHz convex probe (CX50, Philips, Netherlands), which revealed the thickened gastric wall (Figure 1). In the POCUS exam, there were no findings of dilated common bile duct dilatation or thickened gall bladder wall.

Given the physical examination, laboratory test results, and POCUS findings, our differential diagnosis included gastric anisakiasis, acute gastric mucosal lesions, and upper gastrointestinal perforation.

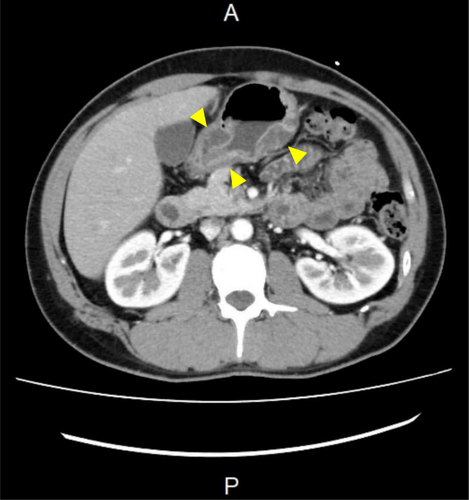

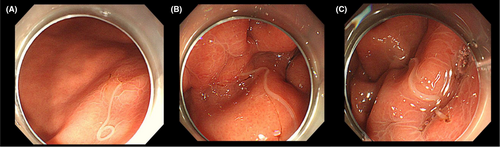

Further evaluation with computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast revealed the edematous and thickened gastric wall (Figure 2). An emergency endoscopy was performed approximately 2 h after POCUS examination and revealed three Anisakis larvae penetrating the gastric mucosa. The first larva was identified in the great curvature of the lower part of the stomach body (Figure 3A). The second larva was identified in the upper posterior wall of the stomach body (Figure 3B). The third larva was identified in the fundus (Figure 3C). All larvae were successfully removed using biopsy forceps. After this treatment, his symptoms were completely resolved. He was discharged on the same day without hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

Anisakiasis is a parasitic zoonotic disease caused by the nematode Anisakis larvae, transmitted to humans through the consumption of raw or undercooked intermediate hosts such as salmon, herring, cod, mackerel, and squid.4 While it has frequently been reported in coastal areas of Asia, cases have emerged globally in recent years.5 Anisakiasis can be broadly classified into three types: (1) gastric anisakiasis, (2) small intestinal anisakiasis, and (3) ectopic or extraintestinal anisakiasis. Gastric anisakiasis accounts for approximately 95% of cases,6 with small intestinal anisakiasis comprising the remainder, while ectopic/extraintestinal anisakiasis is extremely rare. Gastric anisakiasis is characterized by severe epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting, which often occur within hours of ingesting infected fish and can lead to severe allergic reactions. In this case, the patient's acute onset of epigastric pain following the consumption of sushi containing horse mackerel, mackerel, and sardines approximately 12 h earlier raised clinical suspicion for gastric anisakiasis.

Diagnosis of gastric anisakiasis is typically made by detecting larvae during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. However, this procedure is not always readily available in emergency departments and urgent care settings. When gastric anisakiasis is suspected, an abdominal CT scan is generally performed. The most frequent CT findings in patients with gastric anisakiasis include wall stratification with a sensitivity of 100%7, 8 and wall thickening with a sensitivity of 97%.7 Robert et al. reported that ultrasonographic findings of intestinal anisakiasis often reveal ascitic fluid and wall thickening, with sensitivities around 70%.7 There have been no prior reports establishing the accuracy of POCUS in visualizing the gastric wall in gastric anisakiasis, and its diagnostic utility remains uncertain. Ki et al. reported that the normal gastric wall is approximately 4.9 ± 1.6 mm,9 while in cases of gastric anisakiasis, wall thickness has been reported between 10 and 24 mm when stomach contents are present, suggesting the potential for POCUS detection.7 However, as the diagnostic accuracy of POCUS has not been fully validated, we opted to perform a contrast-enhanced CT scan to confirm the gastric wall thickening and rule out other potential causes of acute abdominal pain. While CT scans remain a more definitive diagnostic tool, their availability may be limited in rural or remote areas. In these contexts, POCUS can serve as a valuable diagnostic tool, providing rapid, bedside evaluation, especially when CT scans are not accessible or feasible due to logistical constraints. However, in cases of persistent or severe abdominal pain, where a more detailed and comprehensive assessment is necessary, a CT scan may still be preferred if available. Even in such cases, POCUS can contribute to clinical decision-making in resource-limited settings by helping to determine whether patients need to be transferred to a facility where a CT scan is available.

In our case, the primary suspicion of gastric anisakiasis was based on the patients' clinical history, including recent ingestion of raw fish and subsequent acute abdominal pain. POCUS successfully demonstrated the thickened gastric wall, allowing us to strongly suspect gastric anisakiasis even before conducting the abdominal CT scan. These clinical features were key in directing our initial diagnostic approach. POCUS findings, specifically gastric wall thickening, helped to support this suspicion and prompted further investigation. However, as the diagnostic value of POCUS for gastric anisakiasis has not yet been fully established, the decision was made to perform a contrast-enhanced CT scan to confirm the presence of gastric wall thickening and exclude other causes of acute abdominal diseases. A physician with 14 years of experience performed POCUS. An emergency endoscopy was performed approximately 2 h after the POCUS examination. This case highlights the importance of POCUS when clinicians suspect gastric anisakiasis, especially given its noninvasiveness and low cost. While the typical findings of gastric anisakiasis in the abdominal CT scan are well documented, it is still imperative to evaluate the pre-test probability to ensure the precise and timely diagnosis. Therefore, clinicians should consider routinely using POCUS when gastric anisakiasis is suspected. Gastric POCUS is typically performed with the patient in the supine position; however, when the patient's condition allows, scanning in the right lateral decubitus position may improve the visualization of the gastric antrum and gastric wall. The time required to perform POCUS largely depends on the skill of the clinician performing the examination. It is important to note that POCUS could delay more definitive diagnostic procedures such as endoscopy or CT scan, and there may be a risk of delay in reaching a definitive diagnosis. In our setting, the supervising physician directly oversees the ultrasound process, providing real-time guidance to junior residents to ensure accurate imaging. While this supervision ensures quality control, it can extend the time for image acquisition. With increased training and experience, the time required for POCUS could be reduced, potentially leading to faster diagnosis and management. Therefore, it should be integrated into the clinical workflow in a way that minimizes diagnostic delays. We believe that, with appropriate supervision, early career clinicians can effectively identify gastric wall thickness and integrate the POCUS finding into the decision-making process. POCUS has been widely used in emergency departments, and it is important for clinicians to recognize which conditions can be identified using POCUS, as diagnosing specific conditions can be challenging without prior suspicion and familiarity with their ultrasound appearance.

CONCLUSION

We presented a case of gastric anisakiasis that was suspected based on POCUS findings. Gastric anisakiasis is typically treated promptly with upper gastrointestinal endoscopy; however, it can occasionally lead to critical conditions such as ectopic anisakiasis. Therefore, timely diagnosis is crucial. This case suggests that POCUS can be an effective tool when suspecting gastric anisakiasis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol: N/A.

Informed consent: The patient provided consent for publication.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.