Variation in carbon isotope values among chimpanzee foods at Ngogo, Kibale National Park and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda

Abstract

Stable isotope values in primate tissues can be used to reconstruct diet in the absence of direct observation. However, in order to make dietary inferences, one must first establish isotopic variability for potential food sources. In this study we examine stable carbon isotope (δ13C) values for chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) food resources from two Ugandan forests: Ngogo (Kibale National Park), and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. Mean δ13C values for plant samples are equivalent at both sites. Plant δ13C values are best explained by a multivariate linear model including plant part (leaves, pith, flowers, and fruit), vertical position within the canopy (canopy vs. ground), and taxon (R2 = 0.6992). At both sites, leaves had the lowest δ13C values followed by pith and fruit. Canopy resources have comparable δ13C values at the two sites but ground resources have lower δ13C values at Ngogo than Bwindi (−30.7 vs. −28.6‰). Consequently, isotopic differences between ground and canopy resources (4.2 vs. 2.2‰), and among plant parts are more pronounced at Ngogo. These results demonstrate that underlying environmental differences between sites can produce variable δ13C signatures among primate food resources. In the absence of observation data or isotope values for local vegetation, caution must be taken when interpreting isotopic differences among geographically or temporally separated populations or species. Am. J. Primatol. 78:1031–1040, 2016. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

The application of stable isotope analysis to the study of primate foraging ecology requires an understanding of potential dietary inputs as well as environmentally induced variation. In this article, we focus on quantifying the factors that drive differences in the carbon isotope (δ13C) values of plant foods consumed by wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in two tropical forest habitats in Uganda.

Chimpanzees may serve as an informative model for reconstructing the dietary ecology of extinct apes or early hominins [e.g., see Nelson, 2013]. Wild chimpanzees occupy a range of ecological settings from C3-dominated closed canopy forest to open woodland and savanna. Given their genetic relatedness to humans and their occupation of contemporary environments perhaps not unlike those utilized by our shared late-Miocene ancestors, analyses of chimpanzee feeding behavior and the isotopic signatures of their habitats may provide insight into reconstructions of late-Miocene forest composition and hominoid behavior. Observed feeding behaviors of chimpanzees vary among sites: fruit consumption ranges from 39 to 64%, pith from 5 to 12%, and leaves from 10 to 30% [as reviewed in Pruetz, 2006]. In the absence of observational data, these dietary differences may be distinguishable using isotopic analyses of hair or bone [Carlson & Kingston, 2014; Schoeninger et al., 1999]. However, in order to make inferences about diet, it is important to first establish that isotopic differences among food sources are consistent among chimpanzee habitats.

Most chimpanzee populations have shown extremely little intra-population isotopic variability [Fahy et al., 2013; Nelson, 2013; Oelze et al., 2014; Schoeninger et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2010; Sponheimer et al., 2006], suggesting that observed differences in feeding behavior are not represented in the carbon isotopic composition of their tissues. Comparing mean δ13C values among sites, however, suggests isotopic variability on the order of 3‰ [Cerling et al., 2004; Fahy et al., 2013; Nelson, 2013; Oelze et al., 2014; Schoeninger et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2010; Sponheimer et al., 2006]. It remains unclear if dietary differences, environmental differences, or both are responsible for this variation.

Consistent and predictable isotopic variability across environments is important for ecologically meaningful interpretations using isotopic dietary reconstructions. Rainfall, elevation, and temperature are the primary factors that affect δ13C values in C3 plants at a global scale [Carlson & Kingston, 2014; Crowley et al., 2011; Diefendorf et al., 2010; Kohn, 2010; Körner et al., 1991; Sparks & Ehleringer, 1997]. Additional factors that affect light or water availability at a local or regional scale, such as relative humidity, topography, water use efficiency, rooting depth, and mycorrhizal associations may also impact δ13C values in plants [Blumenthal et al., 2012; Broadmeadow et al., 1992; Carlson & Kingston, 2014; Cerling et al., 2004; Cernusak et al., 2009; Codron et al., 2005; Ehleringer & Cooper, 1988; Ehleringer et al., 1986; Farquhar, 1983; Farquhar et al., 1989; Hobbie et al., 1999; Kohn, 2010; Medina & Minchin, 1980; Schoeninger et al., 1998]. Moreover, understory vegetation growing under dense forest canopies typically has lower δ13C values than vegetation growing under more open conditions. This is due to lower light levels, higher soil moisture, and the accumulation of 13C-depleted CO2 that is respired by soil microbes [Broadmeadow et al., 1992; Medina & Minchin, 1980; Ometto et al., 2006]. Finally, different parts of the same plant (e.g., leaves vs. fruits) may vary isotopically [Carlson & Kingston, 2014]. This is potentially because of differences in the degree to which these parts rely on sucrose that is fixed during the day versus night, or fractionation associated with translocation of photosynthate from leaves [Codron et al., 2005; Cernusak et al., 2009; Blumenthal et al., 2012].

Stable isotope data for individual food items and plant parts (along with chimpanzee tissue or fecal data) have been reported for several chimpanzee study sites [Blumenthal et al., 2012; Fahy et al., 2013; Oelze et al., 2011, 2014], but comparisons among sites have been hampered by limited sample sizes. As a result, detailed comparisons of chimpanzee isotope ecology across sites remain elusive. We assess the degree to which isotopic variability among known chimpanzee foods (fruit, pith, flowers and leaves) is consistent between two forests in western Uganda: Ngogo (Kibale National Park) and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. We test the influence of elevation, vertical position in the canopy, plant part, and species on the δ13C values of plant samples, and discuss the relevance of our results to dietary reconstructions for living and extinct primates.

METHODS

Plant samples were collected from species consumed by resident chimpanzees at Bwindi Impenetrable (0°53–1°08N, 29°35′–29°50′E) and Kibale (0°13′–0°41′N, 30°19′–30°32′E) National Parks. Both sites are located in Western Uganda along the Albertine Rift (Fig. 1), receive 1,400–1,900 mm of annual precipitation [Chapman & Wrangham, 1993; Eilu & Obua, 2005; Ghiglieri, 1984], and support populations of wild chimpanzees. However, the two parks differ in their forest structure and elevation range. At Kibale, samples were collected from the region occupied by the Ngogo chimpanzees, which is located in the middle of the park and is characterized as a closed canopy lowland tropical rain forest interspersed with open grasslands of Pennisetum purpureum [Struhsaker, 1997, p16]. Elevation at Ngogo ranges from 1,250 to 1,500 m. Bwindi Impenetrable is one of the only forests in Africa with relatively continuous forest cover from 1,200 to 2,600 m (although it is less continuously canopied and has more ground vegetation than Ngogo; Carlson, personal observation). Bwindi has been classified as moist lower montane forest [Chaigneau et al., 2010], and contains some of the highest recorded elevations inhabited by wild chimpanzees. Samples were collected between ca. 1,500 and 2,600 m. We previously found a negative association between elevation and δ13C values across the 250 m of elevation change at Ngogo [Carlson & Kingston 2014]. Given its similar rainfall regime but substantial elevation range and different vegetation structure, Bwindi Impenetrable National Park was selected as a suitable location for testing inter-site isotopic variability.

Fieldwork and sample collection was approved by the Ugandan National Council of Science and Technology and the Ugandan Wildlife Authority, and adhered to the American Society of Primatologists principles for the ethical treatment of primates. Data for samples at Kibale are previously published [Carlson & Kingston, 2014]. However, we include details about specimen collection here to illustrate differences in how vegetation samples may be collected and preserved in the field. Plant foods were identified from the literature [Watts et al., 2012], personal observation (BAC), field assistants, and a local expert (Jerry Lwanga). Collection occurred during three weeks in late November and early December 2009 and 8 weeks in June and July 2010. Samples were collected at the approximate stage of maturation most consumed by resident chimpanzees. For example, where ripe fruit and young leaves were preferred, sampling would not include unripe fruit or mature leaves. All foods were collected directly from the tree/plant when accessible without climbing gear (all leaves and pith), or the ground after falling from the canopy naturally (most fruit and flowers). To minimize the potential for contamination or isotopic changes associated with decay, samples with mold, bruising, insect damage, or bite marks were excluded. Samples were dried in the field on the day of collection at 65–77° for up to 3.5 hr using a kerosene fueled stove.

Plant foods consumed by Bwindi chimpanzees were identified from the literature [Stanford & Nkurunungi, 2003] and personal observations of local field assistants. Plant species were identified in the forest by BAC and field assistants, with unknown samples identified or confirmed by a local expert (Robert Barigyira). Samples were collected over the course of two weeks in June 2012 and 1 week in December 2012. Samples were pressed in paper and dried over charcoal stoves. The plant press was placed on a wire rack approximately 1.5 m off the ground. Charcoal stoves (about 30 cm tall) were ignited away from the plant press, and a thick layer of ash poured over the top to quench flames and maintain temperatures below 65°C. Once the stoves began burning without smoke, they were placed under the rack and samples were left to dry overnight.

Isotopic analyses of all plant samples were conducted at the Analytical Chemistry Laboratory in the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia. Samples were run on a Carlo Erba NA-1500 CN Elemental Analyzer coupled to a Thermo Delta V magnetic sector IRMS via a Thermo Conflo III Interface. Analytical error was assessed using an in-house poplar standard for elemental analysis and a bovine collagen standard (NIST 1577-B) for isotopic analysis, with one replicate of each run after every 10 unknown samples. All δ13C values are reported in reference to the international V-Pee Dee Belemnite standard.

Statistical analyses were performed using the R program for statistical computing [R Core Team, 2013] and significance was set at α = 0.05. Previously published data from Ngogo [Carlson & Kingston, 2014] were reanalyzed and modeled with the newly collected data from Bwindi. Based on previous results by Carlson and Kingston [2014], multivariate linear models were built stepwise to examine carbon isotopic variation attributable to the following variables: plant part, position within the forest canopy, taxon (defined as species for most samples, and genus for those unidentifiable at the species level), site, and elevation. Because previous analyses at Ngogo indicated no isotopic differences between dry and wet seasons [Carlson & Kingston, 2014], seasonality was not included in these analyses. Additionally, as both parks receive similar amounts of rainfall, precipitation was similarly not included in these analyses.

We divided samples into four “part” categories (fruit, leaves, pith, flowers), which are consumed by chimpanzees at both sites. We also divided samples into two categories based on their canopy position during growth (not necessarily where they were collected): “ground” (0–3 m) and “canopy” (>10 m). Elevation was measured for each sample using a handheld GPS unit. Goodness of fit was assessed by adjusted R-square (herein reported simply as R2) and Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was also used on the full model (with all explanatory variables included) to further examine the degree to which each variable contributes to variation in δ13C values. Isotopic differences between sites were assessed using Welch's Two Sample t-tests.

RESULTS

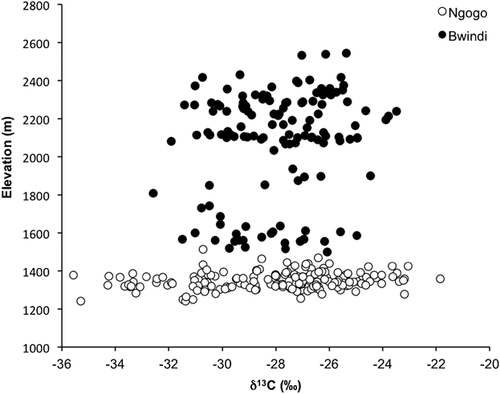

Models

Mean δ13C values for chimpanzee plant foods are isotopically equivalent at Ngogo and Bwindi: −28.0 ± 2.8‰ (n = 198) and −27.9 ± 1.9‰ (n = 132), respectively. The range in δ13C values is 13.8‰ at Ngogo and 9.1‰ at Bwindi (Fig. 2). Among the taxa with more than one sample, sapling leaves of Morus lactea have the lowest δ13C values (−33.7 ± 1.0‰), and Pterygota mildbraedii flowers have the highest values at Ngogo (−24.4 ± 1.0‰) (Table I). At Bwindi, Mimulopsis leaves have the lowest δ13C values (−31.3 ± 1.1‰) and Podocarpus milinjianus fruit have the highest values (−24.6 ± 1.1‰) (Table II).

| Taxon | Canopy location | Food type | n | δ13C Mean ± 1 SD (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthus sp. | Ground | Pith | 7 | −29.4 ± 2.3 |

| Afromomum sp. | Ground | Pith | 8 | −29.4 ± 2.3 |

| Aningeria altissima | Canopy | Fruit | 5 | −25.7 ± 1.5 |

| Celtis africana | Ground | Leaves | 9 | −28.5 ± 2.4 |

| Celtis durandii | Canopy | Fruit | 5 | −26.2 ± 0.8 |

| Celtis mildbraedii | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −30.3 ± 0.8 |

| Chaetacme aristata | Ground | Leaves | 5 | −28.9 ± 1.8 |

| Chrysophyllum albidum | Canopy | Fruit | 9 | −27.3 ± 0.9 |

| Cordia millenii | Canopy | Flowers | 2 | −25.8 ± 1.1 |

| Cordia millenii | Canopy | Fruit | 3 | −26.4 ± 1.5 |

| Ficus brachylepis | Canopy | Fruit | 5 | −28.3 ± 1.6 |

| Ficus dawei | Canopy | Fruit | 3 | −26.0 ± 0.9 |

| Ficus exasperata | Canopy | Fruit | 7 | −26.3 ± 1.4 |

| Ficus mucuso | Canopy | Fruit | 9 | −26.9 ± 0.3 |

| Ficus natalensis | Canopy | Fruit | 6 | −26.9 ± 0.8 |

| Marantochloa sp. | Ground | Pith | 5 | −32.3 ± 1.7 |

| Mimusops bagshawei | Canopy | Fruit | 6 | −26.7 ± 0.9 |

| Monodora myristica | Canopy | Flowers | 10 | −26.6 ± 1.4 |

| Monodora myristica | Canopy | Fruit | 8 | −27.9 ± 2.3 |

| Monodora myristica | Ground | Leaves | 6 | −32.1 ± 1.4 |

| Morus lactea | Canopy | Flowers | 5 | −24.5 ± 0.8 |

| Morus lactea | Canopy | Fruit | 5 | −25.4 ± 0.5 |

| Morus lactea | Ground | Leaves | 9 | −33.7 ± 1.0 |

| Neoboutonia macrocalyx | Canopy | Fruit | 5 | −27.6 ± 0.8 |

| Piper sp. | Ground | Pith | 9 | −31.3 ± 1.4 |

| Pseudospondias microcarpa | Canopy | Fruit | 4 | −27.3 ± 0.6 |

| Pterygota mildbraedii | Canopy | Flowers | 10 | −24.4 ± 1.0 |

| Pterygota mildbraedii | Canopy | Fruit | 6 | −27.5 ± 1.3 |

| Pterygota mildbraedii | Ground | Leaves | 9 | −30.9 ± 1.0 |

| Treculia africana | Canopy | Fruit | 4 | −26.0 ± 1.4 |

| Uvariopsis congensis | Canopy | Fruit | 5 | −27.4 ± 0.6 |

| Warburgia ugandensis | Canopy | Fruit | 6 | −24.6 ± 2.2 |

| Total | 198 | −28.0 ± 2.8 |

| Taxon | Canopy Location | Food Type | n | δ13C Mean ± 1 SD (‰) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthus sp. | Ground | Pith | 2 | −26.9 ± 0.7 |

| Aframomum sp. | Ground | Fruit | 1 | −29.7 |

| Aframomum sp. | Ground | Pith | 3 | −30.9 ± 0.7 |

| Alchornea hirtella | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −28.1 ± 0.4 |

| Arundinaria alpina | Ground | Pith | 3 | −26.2 ± 0.8 |

| Carapa grandiflora | Both | Leaves | 2 | −28.9 ± 1.0 |

| Cardus sp. | Ground | Flowers | 2 | −31.2 ± 0.3 |

| Cardus sp. | Ground | Leaves | 2 | −30.8 ± 0.4 |

| Cassipourea sp. | Ground | Flowers | 1 | −28.5 |

| Cassipourea sp. | Ground | Leaves | 1 | −28.9 |

| Chrysophyllum albidum | Canopy | Fruit | 1 | −25.3 |

| Chrysophyllum gorungosanum | Canopy | Fruit | 4 | −27.0 ± 0.6 |

| Clematis sp. | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −28.8 ± 1.5 |

| Dombeya sp. | Ground | Fruit | 3 | −29.6 ± 0.7 |

| Dombeya sp. | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −29.6 ± 0.7 |

| Ficus capensis | Canopy | Fruit | 2 | −26.3 ± 1.0 |

| Ficus natalensis | Canopy | Fruit | 3 | −28.2 ± 1.4 |

| Ficus pilosula | Ground | Leaves | 1 | −31.9 |

| Ficus spp. | Both | Fruit | 6 | −27.8 ± 2.3 |

| Galiniera saxifraga | Ground | Fruit | 3 | −26.9 ± 0.7 |

| Laplaea mayombensis | Both | Fruit | 2 | −26.4 ± 2.0 |

| Maesa lanceolata | Both | Fruit | 4 | −27.3 ± 1.9 |

| Mimulopsis sp. | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −31.3 ± 1.1 |

| Mormodica calantha | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −29.7 ± 0.5 |

| Mormodica foetida | Ground | Fruit | 3 | −29.5 ± 0.6 |

| Mormodica foetida | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −29.9 ± 0.7 |

| Musanga sp. | Canopy | Fruit | 1 | −27.1 |

| Myrianthus holstii | Ground | Fruit | 2 | −29.5 ± 0.0 |

| Mystroxylon aethiopica | Canopy | Fruit | 2 | −26.6 ± 0.9 |

| Olea capense | Canopy | Fruit | 1 | −26.1 |

| Olinia usambaransis | Canopy | Fruit | 3 | −26.1 ± 0.8 |

| Parinari holstii | Canopy | Fruit | 2 | −28.3 ± 0.2 |

| Piper capense | Ground | Pith | 3 | −29.2 ± 1.5 |

| Podocarpus millinjianus | Canopy | Fruit | 6 | −24.6 ± 1.1 |

| Prunus africana | Canopy | Leaves | 3 | −26.0 ± 0.5 |

| Rhytiginia spp. | Ground | Fruit | 3 | −27.7 ± 1.8 |

| Rubia cordifolia | Ground | Leaves | 1 | −29.4 |

| Rubia cordifolia | Ground | Pith | 1 | −29.2 |

| Rubus sp. | Ground | Fruit | 5 | −27.4 ± 1.0 |

| Rubus sp. | Ground | Leaves | 3 | -28.2 ± 0.8 |

| Smilax anceps | Ground | Fruit | 2 | −26.1 ± 2.3 |

| Strombosia sp. | Canopy | Fruit | 2 | −26.7 ± 1.5 |

| Symphonia globulifera | Canopy | Flowers | 3 | −26.8 ± 0.6 |

| Symphonia globulifera | Canopy | Fruit | 3 | −27.8 ± 0.6 |

| Syzigium spp. | Canopy | Fruit | 2 | −25.3 ± 0.5 |

| Tabernamontana holstii | Both | Fruit | 4 | −27.1 ± 2.1 |

| Teclea nobilis | Ground | Fruit | 2 | −29.1 ± 1.1 |

| Triumphetta sp. | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −29.0 ± 0.4 |

| Unidentified liana | Ground | Fruit | 2 | −29.3 ± 1.7 |

| Veronia sp. | Ground | Pith | 3 | −26.9 ± 0.7 |

| Xymalos monspora | Ground | Leaves | 3 | −28.6 ± 2.0 |

| Total | 132 | −27.9 ± 1.9 |

Four multivariate models produce equivalent R2 of approximately 0.70 (Table III). While the full model (δ13C as a function of plant part, canopy position, taxon, elevation, and site) produces the highest R2 with the lowest AIC value, a reduced model with just canopy position, plant part, and taxon produces a nearly equivalent R2 and AIC (Table III). Stepwise model building reveals that canopy position and plant part account for approximately 46% of the total variance in δ13C values, with taxon, elevation, and site accounting for an additional 23.7, 6.7, and 4.7% respectively.

| Linear models | Adjusted R2 | AIC | F-value (df) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Taxon + Elevation + Site | 0.7059 | 1,200.6 | 5.77 (162,160) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Taxon + Site | 0.7059 | 1,202.4 | 9.88 (89,240) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Taxon | 0.6992 | 1,208.7 | 9.79 (87,242) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Taxon + Elevation | 0.6956 | 1,211.7 | 5.63 (159,163) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Elevation + Site | 0.5410 | 1,265.6 | 19.97 (20,302) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Elevation | 0.5288 | 1,266.5 | 31.12 (12,310) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Site | 0.5095 | 1,307.1 | 35.18 (10,319) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position | 0.4622 | 1,339.7 | 46.27 (6,323) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Elevation + Taxon (Site = Ngogo) | 0.7491 | 717.79 | 10.15 (62,128) | <0.0001 |

| Plant Part + Canopy Position + Elevation + Taxon (Site = Bwindi) | 0.6863 | 407.29 | 3.89 (99,32) | <0.0001 |

| ANOVAa | F-value (df) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Part | 3.98 (9) | <0.0001 |

| Canopy Position | 58.41 (1) | <0.0001 |

| Taxon | 4.25 (64) | <0.0001 |

| Elevation | 51.63 (1) | <0.0001 |

| Site | 0.46 (1) | 0.5 |

| Plant Part * Canopy Position | 5.92 (2) | <0.01 |

| Plant Part * Taxon | 3.77 (10) | <0.001 |

| Canopy Position * Taxon | 3.348 (5) | 0.097 |

| Elevation * Taxon | 92.48 (57) | 0.633 |

- a ANOVA includes all variables: Plant Part + Canopy Position + Taxon + Elevation + Site.

Analysis of variance for the full model reveals significant contributions of plant part, canopy position, taxon, and elevation to the variation in δ13C values (Table III). Among the several interactions tested, only plant part + canopy and plant part + taxon are significant (discussed in more detail below). Controlling for other variables in the model, there is no variation in δ13C values attributable to site. This result is consistent with equivalent mean δ13C values between sites and multivariate linear models, which reveal roughly equivalent goodness of fits with or without study site included (Table III).

Canopy Position

Canopy resources routinely have higher δ13C values than those close to the ground [Broadmeadow et al., 1992; Cerling et al., 2004; Medina & Minchin, 1980]. This is true for both Bwindi and Ngogo, but the isotopic difference between canopy and ground resources is significantly greater at Ngogo (Table IV). Whereas canopy resources are isotopically equivalent at both sites, ground resources at Ngogo are 2.1‰ lower than those at Bwindi (P < 0.0001).

| Category | Ngogo | Bwindi | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canopy | −26.5 ± 1.6 (128) | −26.4 ± 1.3 (42) | −0.1 |

| Ground | −30.7 ± 2.3 (70) | −28.6 ± 1.7 (90) | −2.1** |

| Leaves | −30.9 ± 2.4 (41) | −29.1 ± 1.6 (37) | 1.8** |

| Pith | −30.5 ± 2.1 (29) | −28.2 ± 2.0 (15) | 2.3** |

| Fruit | −26.8 ± 1.5 (101) | −27.2 ± 1.7 (74) | −0.4 |

| Flowers | −25.3 ± 1.5 (27) | −28.6 ± 2.2 (6) | −3.3* |

| All samples | −28.0 ± 2.8 (198) | −27.9 ± 1.9 (132) | 0.1 |

- All values are reported in (‰).

- * P < 0.05.

- ** P < 0.001.

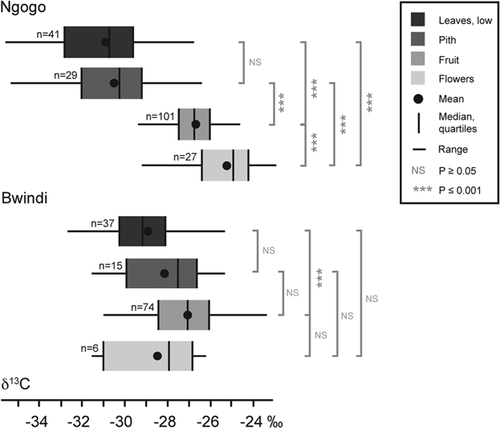

Plant Part

There are significant differences in δ13C values between sites for leaves, pith, and flowers (Table IV). Pairwise comparisons between plant parts reveal significant differences among most parts at Ngogo, but not at Bwindi (Fig. 3). At both sites, leaves have the lowest δ13C values, followed by pith, and fruit (Fig. 3). At Ngogo, flowers have the highest δ13C values, whereas at Bwindi, they are intermediate between leaves and pith. While the multivariate linear models and ANOVA both indicate that variation in δ13C values is attributable to plant part independently of other variables, there is also a strong interaction between canopy position and plant part. At both sites, all leaf and pith samples were collected at ground level, and most fruit and flower samples came from the canopy (Tables I and II). However, at Bwindi, some sampled flowers (specifically those from the genus Cardus), grow close to the ground, which could lower the mean δ13C value for flowers at this site.

Taxon

There are significant differences in δ13C values among taxa (Table III). A highly significant interaction between taxon and plant part suggests that this difference may be largely attributable to uneven representation of plant parts among taxa as well as small differences in the degree to which various taxa are represented by ground versus canopy samples. Additionally, isotopic differences between woody and herbaceous vegetation, as well as variation in rooting depth or mycorrhizal associations may help explain some of the isotopic differences among taxa [Heaton, 1999; Hobbie et al., 1999].

Elevation

Similar to a previous analysis for plants at Ngogo [Carlson & Kingston, 2014], ANOVA results suggest that δ13C values vary with elevation (after controlling for plant part and canopy position). However, the effects of elevation are relatively minor compared to plant part, canopy position, and taxon (Table III). Plotting elevation against δ13C values confirms a relatively superficial role for elevation as a driver of isotopic variability (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

On average, plants collected at Bwindi and Ngogo are isotopically indistinguishable. However, site averages mask distinctive patterns of isotopic variation between sites. Variability in δ13C values for plants at both Ngogo and Bwindi is attributable to vertical position in the canopy, plant part, taxon, and elevation, and the explanatory power of these variables varies between sites. This inter-site isotopic variability has significant implications for reconstructing feeding behavior at sites where the underlying isotopic ecology has not been, or cannot be, defined (e.g., historic or fossil localities).

Inter-Site Differences in δ13C Values Between Canopy and Ground Resources

Vertical position of food resources is the most consistent and substantial driver of variation in δ13C values at both Ngogo and Bwindi. However, the magnitude of this effect differs between sites (4.2‰ between canopy and ground resources at Ngogo vs. 2.2‰ at Bwindi). This difference is attributable to lower δ13C values for ground resources at Ngogo (Table III). The more pronounced canopy effect at Ngogo could reflect the denser canopy at this site compared to Bwindi [Buchmann et al., 1997; Graham et al., 2014]. Additionally, higher respiration rates by soil microbes or a larger temperature or humidity gradient between the ground and canopy at Ngogo could explain the more pronounced canopy effect at this site [Broadmeadow et al., 1992; Lloyd et al., 1996; Striegl & Wickland, 2001]. Finally, it is possible that a portion of the observed isotopic difference in ground resources between Bwindi and Ngogo results from differences in what was sampled at the two sites (e.g., variability in the degree to which herbaceous vs. woody understory vegetation was sampled [see Blumenthal et al., 2012; Heaton, 1999; Scarano et al., 2001]).

Inter-Site Differences in δ13C Values Among Plant Parts

Differences in the degree to which canopy and ground resources differ isotopically at Bwindi and Ngogo also impacts isotopic differences between plant parts at the two sites. Chimpanzee food resources at Ngogo and Bwindi are typically either found near the ground or ca. 30–40 m in the canopy. Pith (from terrestrial herbaceous vegetation) and young leaves from tree saplings are found near the ground, fruit and flowers typically grow in the canopy, and fallen fruits or flowers on the forest floor maintain their “canopy” isotopic signature [Cerling et al., 2004].

At Ngogo, where ground resources have lower δ13C values than at Bwindi, we find isotopic differences between nearly all plant parts sampled (Fig. 3). Lower δ13C values for leaves and pith at Ngogo than Bwindi can also be explained by the more pronounced canopy effect at Ngogo. The smaller isotopic difference between canopy and ground resources at Bwindi likely reduces the magnitude of isotopic differences among plant parts. Additionally, the lower mean δ13C values for flowers at Bwindi likely reflects the influence of Cardus flowers, which grow at ground level.

The Role of Elevation

Previous analyses from Ngogo suggested that elevation contributes to variation in δ13C values over a range of only about 250 m [Carlson & Kingston, 2014]. Analysis of variance results for our full model suggest a significant interaction between elevation and δ13C values. However, linear regressions indicate that the effect of elevation on sample δ13C values is equivocal, despite more than 1,000 m of elevation change among samples collected at Bwindi (Table III, Fig. 2). Given that the effects of elevation are negligible compared to those of canopy cover, plant part, and taxon, controlling for its influence in dietary reconstruction models may be unnecessary. This finding is similar to those of larger analyses, which also found the influence of elevation to be relatively minor [Diefendorf et al., 2010; Kohn, 2010].

Implications

Our results have major implications for isotopically distinguishing dietary differences within and among populations inhabiting C3-dominated systems. At sites like Ngogo, where there are significant isotopic differences among plant parts, it may be possible to assess inter-individual or temporal differences in feeding behavior using isotopic analysis of hair or feces. Detecting diet at a site like Bwindi, however, where isotopic differences among plant parts are smaller in magnitude or non-existent, will remain challenging if bulk δ13C values are used alone.

Without accounting for baseline differences in δ13C values between sites, it would be easy to misinterpret differences in δ13C values for chimpanzees at Bwindi and Ngogo. Identical feeding behavior at these two sites would produce different tissue signatures on account of the underlying isotopic differences in ground resources. Variation in the degree to which canopy and ground resources differ isotopically among sites may also explain some of the previously recorded variability in δ13C values among chimpanzee populations [Cerling et al., 2004; Fahy et al., 2013; Nelson, 2013; Oelze et al., 2014; Schoeninger et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2010; Sponheimer et al., 2006].

Dietary reconstruction via stable isotopic analysis requires knowledge of local underlying isotopic variability. In the absence of this information, one should take extreme caution when interpreting differences in δ13C values among populations or allopatric species as real differences in feeding behavior. For dietary reconstruction in modern environments, this may simply require systematic analyses of plant material from relevant habitats [e.g., Blumenthal et al., 2012; Cerling et al., 2004; Codron et al., 2005; Crowley et al., 2013; Dammhahn & Kappeler, 2010; Fahy et al., 2013; Oelze et al., 2011, 2014; van der Merwe & Medina, 1991]. Reconstruction of feeding behavior for extinct organisms, however, may be more difficult. In these contexts, analyses from co-occurring taxa with more well-defined foraging ecologies (e.g., browsing and grazing ungulates, and arboreal taxa) may provide a reasonable baseline [e.g., Drucker et al., 2008; Lee-Thorp et al., 2010; Nelson, 2007; Secord et al., 2008; White et al., 2009]. Additionally, adding a second isotope (e.g., oxygen) could add further information about habitat heterogeneity and isotopic differences among fruits and leaves [Carter & Bradbury, 2016; Cerling et al., 2004; Crowley et al., 2015; Krigbaum et al., 2013; Lee-Thorp et al., 2010; Nelson, 2013; Secord et al., 2008; White et al., 2009].

CONCLUSION

Plant part, taxon, and canopy position all affect δ13C values for plants from Ngogo and Bwindi forests in Uganda. Canopy position has the most pronounced effects, and differences in the degree to which canopy and ground resources differ isotopically impact other variables. For example, the reduced isotopic difference between ground and canopy resources at Bwindi reduces isotopic differences among plant parts at this site. Our results indicate that isotopic patterns among food resources at one site may not be applicable at another (even in the same region). This variability between sites in the degree to which food resources differ isotopically has implications for dietary reconstruction efforts in contemporary or past environments. Isotopic differences between populations could result from dietary differences, underlying environmental differences, or both. Analysis of underlying environmental isotopic variation should be included whenever possible. In the absence of this environmental context, it will be challenging to confidently interpret the diet of an individual or population on the basis of tissue isotope δ13C values alone.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the Ugandan National Council of Science and Technology and the Ugandan Wildlife Authority for access to Kibale and Bwindi Impenetrable National Parks, and the staff of the Institute of Tropical Forest Conservation for facilitating collection at Bwindi. Many thanks to the field assistants and staff at Ngogo and Bwindi who provided invaluable assistance in plant identification and collection, including Benon Twehikire, Steven Tushemereirwe, and Robert Bitariho at Bwindi, and Godfrey Mbabazi, Lawrence Ndangizi, and Jerry Lwanga at Ngogo. For their assistance with drying and processing samples in the lab, we would like to acknowledge the efforts of Nicholas Barton, Bridget Coverick, Jared Kerzner, and Yinan Zhang. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their thoughtful comments and critique.