Costello syndrome: An overview

Abstract

The Costello syndrome is characterized by prenatally increased growth, postnatal growth retardation, coarse face, loose skin resembling cutis laxa, nonprogressive cardiomyopathy, developmental delay, and a outgoing, friendly behavior. Patients can develop papillomata, especially around the mouth, and have a predisposition for malignancies (mainly abdominal and pelvic rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood). Costello syndrome is likely to be an autosomal dominant disorder. The pathogenesis is unclear, but there are many clues for a disturbed elastogenesis, possibly through a disturbed elastin-binding protein reuse by chondroitin sulfate-bearing proteoglycans accumulation. A review of the findings in the 73 patients that have been described in sufficient detail is provided. © 2003 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

HISTORY

In 1971, J.M. Costello from Auckland, New Zealand, reported at a meeting two unrelated children with mental retardation, high birth weight, neonatal feeding problems, curly hair, coarse face nasal papillomata, and loose integument of the back of the hands [Costello, 1971]. The two children were reported in more detail in 1977 [Costello, 1977]. In the following years, several similar cases were presented at different meetings [Carey et al., 1981; Hall et al., 1990; Berberich et al., 1991] or published [Patton et al., 1987 (Case 5)] without being recognized to have the same entity. The papers of Dr. Costello remained essentially unrecognized until 1991, when Der Kaloustian et al. [1991] reported an additional patient and named the condition Costello syndrome (MIM 218040).

The papers of Dr. Costello remained essentially unrecognized until 1991, when Der Kaloustain et al. reported an additional patient and named the condition Costello syndrome.

Subsequently, the earlier described cases were recognized as cases with Costello syndrome [Johnson et al., 1992; Patton and Baraitser, 1993]. The entity named facio-cutaneous-skeletal syndrome and published in 1992 as a separate entity [Borochowitz et al., 1992] was also recognized to be the same entity [Borochowitz et al., 1993; Der Kaloustian, 1993; Martin and Jones, 1993; Philip and Mancini, 1993; Teebi, 1993]. Costello syndrome was diagnosed in many other patients, and received still more attention when the increased tendency to develop malignancies became clear. The original patients were updated again in 1996 [Costello, 1996].

In total, 84 cases have been described. This review describes the findings in 73 patients (the data on 11 cases are insufficiently reported [Hinek et al., 2000; Gripp et al., 2002 (cases 4 and 5)] or in a language unknown to this author [Fujikawa et al., 2001]; data on only the cardiac findings in 27 patients were reported in an abstract [Lin et al., 2001]), and discusses costello syndrome's possible etiology and pathogenesis. A summary of the clinical data is presented in Table I. Previous reviews are those of Philip and Sigaudy [1998] and Van Eeghen et al. [1999].

| Symptom | Number | Percentagea |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 35M/38F | |

| Pregnancy | ||

| Polyhydramnios | 39/67 | 58 |

| Birth weight >50th centile | 54/61 | 89 |

| Growth and development | ||

| Postnatal growth retardation | 67/70 | 96 |

| Poor neonatal feeding | 56/58 | 97 |

| Hypotonia | 24/32 | |

| Seizures | 6/15 | |

| Developmental delay | 66/66 | 100 |

| Outgoing personality | 47/53 | |

| Hoarse voice | 33/36 | |

| Craniofacial characteristics | ||

| Macrocephalyb | 58/69 | 84 |

| Coarse face | 70/72 | 97 |

| Thick eyebrows | 28/48 | |

| Downslanting palpebral fissures | 40/47 | |

| Epicanthal folds | 49/60 | 82 |

| Strabismus | 24/44 | |

| Depressed nasal bridge | 55/61 | 90 |

| Low-set ears | 55/66 | 83 |

| Large, fleshy ear lobes | 49/55 | 89 |

| Full cheeks | 49/53 | 92 |

| Short, bulbous nose | 50/65 | 77 |

| Large mouth | 41/55 | 75 |

| Thick lips | 64/66 | 97 |

| Macroglossia | 32/45 | |

| Gingival hyperplasia | 13/20 | |

| Apparently highly arched palate | 15/25 | |

| Teeth anomalies | 17/19 | |

| Musculoskeletal characteristics | ||

| Short neck | 43/49 | 88 |

| Increased anterior-posterior thorax diameter | 33/46 | |

| Hernia | 18/30 | |

| Limited extension of elbow | 30/39 | |

| Hyperextensible fingers | 54/62 | 87 |

| Broad distal phalanges | 29/33 | |

| Tight achilles tendons | 30/33 | |

| Abnormal foot position | 35/44 | |

| Delayed bone age | 20/24 | |

| Skin characteristics | ||

| Curly, sparse hair | 53/65 | 82 |

| Loose skin of hands and feet | 70/71 | 99 |

| Deep palmar/plantar creases | 56/56 | 100 |

| Hyperkeratosis | 23/34 | |

| Hyperpigmentation | 39/51 | 76 |

| Dysplastic/thin/deep-set nails | 26/35 | |

| Papillomata | 29/60 | 48 |

| Cardiovascular characteristics | ||

| Congenital heart defects | 23/44 | |

| Dysrhythmia | 27/51 | 53 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 31/51 | 61 |

- * Costello [1971]; Costello [1977]; Berberich et al. [1991]; Der Kaloustian et al. [1991]; Martin and Jones [1991]; Borochowitz et al. [1992]; Di Rocco et al. [1993]; Izumikawa et al. [1993]; Kondo et al. [1993]; Patton and Baraitser [1993]; Philip and Mancini [1993]; Say et al. [1993]; Teebi and Shaabani [1993]; Yoshida et al. [1993]; Zampino et al. [1993]; Costa et al. [1994]; Davies and Hughes [1994b]; Fryns et al. [1994]; Okamoto et al. [1994]; Vila Torres et al. [1994]; Wulfsberg et al. [1994]; Czeizel and Tímár [1995]; Torrelo et al. [1995]; Umans et al. [1995]; Costello [1996]; Fryns et al. [1996]; Fukao et al. [1996]; Mori et al. [1996]; Popa et al. [1996]; Johnson et al. [1998]; Kerr et al. [1998]; Pratesi et al. [1998]; Siwik et al. [1998]; Suri and Garrett [1998]; Tomita et al. [1998]; Yetkin et al. [1998]; Assadi et al. [1999]; Bisogno et al. [1999]; Feingold [1999]; Franceschini et al. [1999]; Szalai et al. [1999]; Van Eeghen et al. [1999]; Flores-Nava et al. [2000]; Gripp et al. [2000]; Hou and Tunnessen [2000]; Moroni et al. [2000]; Sigaudy et al. [2000]; Boente et al. [2001]; Gripp et al. [2002]; Kaji et al. [2002].

- a Percentage only provided if a symptom was at least described in 2/3rd of the cases.

- b Absolute (OFC > 98th centile) or relative to length (OFC > 50th centile at length <3rd centile).

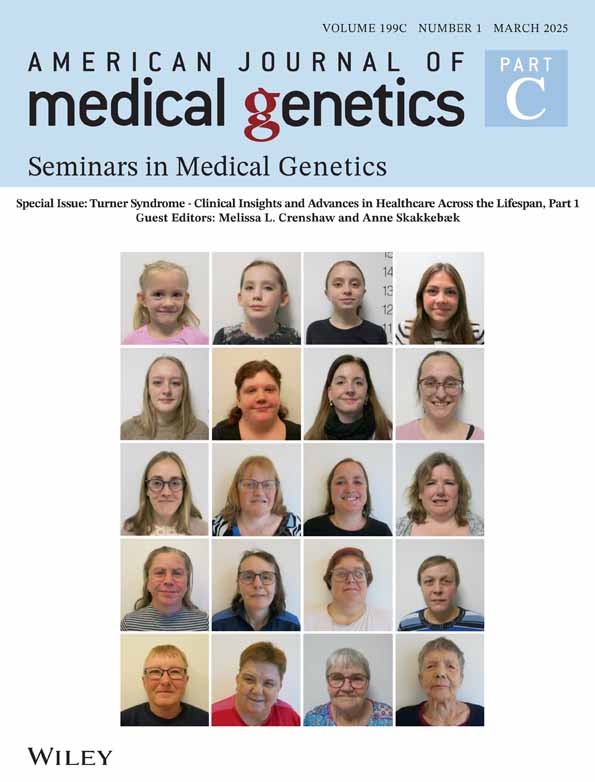

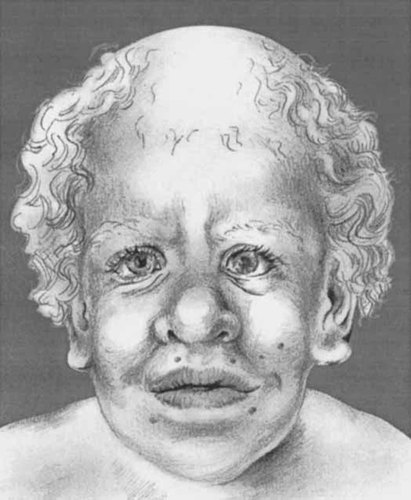

FACIAL CHARACTERISTICS

The major facial symptoms that allow recognition of Costello syndrome are an absolute or relative macrocephaly, with a somewhat hirsute forehead, curly and often sparely implanted hair, thick eyebrows, epicanthal folds, strabismus, downward slanted palpebral fissures, low-set pinnae with often remarkably large ear lobes, and a depressed nasal bridge. The combination of macrocephaly with a bulbous nose, full cheeks, large mouth, thick lips, and large tongue gives the facies almost invariably a coarse impression.

The combination of macrocephaly with a bulbous nose, full cheeks, large mouth, thick lips, and large tongue gives the facies almost invariably a course impression.

Indeed, some patients have initially been suspected to have Hurler syndrome [Van Eeghen et al., 1999] and other mucopolysaccharidoses [Hinek et al., 2000]. Several other facial symptoms have been reported [Van Eeghen et al., 1999], the most frequent ones being large and persistent anterior fontanels, prominent scalp veins, hypertelorism, and capillary hemangioma over the glabella. Rare but possibly important malformations are chorioretinal dystrophy [Di Rocco et al., 1993; Assadi et al., 1999], cataract at birth [Johnson et al., 1998] or at the age of 32 years [Suri and Garrett, 1998], choanal stenosis [Boente et al., 2001], and a congenital laryngeal web [Say et al., 1993]. Figure 1

Drawing of face of patient with Costello syndrome. Note the relative macrocephaly, curly and sparely implanted hair, thick eyebrows, strabimus, downward slanted palpebral fissures, depressed nasal bridge, bulbous nose, large mouth with thick lips, and low-set pinnae with large lobes. The total face has a coarse impression.

At intraoral inspection, hypertrophy of the gingiva, a large tongue, and an apparently highly arched palate are often noted. Sometimes a bifid uvula was found [Izumikawa et al., 1993; Mori et al., 1996]. The teeth may be burried in the gingiva, widely spaced, and have expressed caries.

MUSCULO-SKELETAL MANIFESTATIONS

The short neck accentuates the frequent increase of the anterior–posterior chest diameter. Inguinal hernias are common. Usually there is a generalized hypermobility of the joints, which is most expressed in the fingers. However, the elbows and sometimes also other joints (the knees and wrists) can show a diminished extension. The carrying angle in the elbow may be increased. There are often positional abnormalities in the feet like talipes and vertical talus, and in the hands one may notice a similar positional anomaly in the ulnar deviation of the hands. Many authors report on the tightness of the Achilles tendons which often has needed surgical correction. Other symptoms may be wide distal phalanges of the fingers, kyphoscoliosis, and pectus carinatum or excavatum. Radiographicaley large or late-closing anterior fontanels, osteoporotic long bones, and a delay in bone age have been found. Bone age may be advanced during puberty, however [Assadi et al., 1999; Gripp et al., 2000].

Unusual symptoms are spina bifida occulta [Szalai et al., 1999; Van Eeghen et al., 1999; Gripp et al., 2000], wormian bones [Gripp et al., 2000], and elbow subluxation [Zampino et al., 1993].

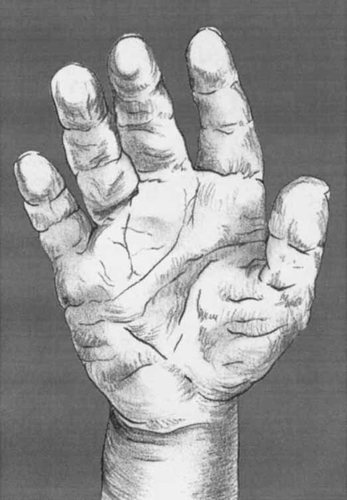

SKIN MANIFESTATIONS

The most striking cutaneous sign in Costello syndrome is the redundant skin of especially the neck, hands, and feet. The skin is thickened, and soft and velvety in feel. As this is most expressed in the palms of the hands and plantar surfaces of the feet, this causes deep creases. The skin over the digital pulps is also loose, like that of one whose hands have been in water overly long. Some authors have reported the presence of persistent fetal pads. With age, palmar and plantar hyperkeratoses are noted. The skin color is darker (olive color) than normal, usually again on the hands and feet but also elsewhere like around the mouth. The presence of acanthosis nigricans has been reported, although it is often unclear how this was defined. Multiple pigmented nevi may be present [Martin and Jones, 1991; Say et al., 1993; Teebi and Shaabani, 1993; Davies and Hughes, 1994b; Torrelo et al., 1995]. The nails can be thin, deeply set, hyperconvex, and dysplastic. Figure 2

Drawing of palms of hand in patient with Costello syndrome. Note the redundant, thickened skin with deep creases, and persistent fetal pads. The skin over the palm and digits resembles that of one whose hands have been in water overly long.

The second major skin symptom is the presence of papillomata. Only about half of the patients develop papillomata. They are usually not present in the newborn, but develop between the 2nd and 15th year.

The second major skin symptom is the presence of papillomata. Only about half of the patients develop papillomata. They are usually not present in the newborn, but develop between the 2nd and 15th year.

They can be found not only around the nose and mouth, but also over the joints (axilla, elbow, knee), abdomen, and perianally. The hoarse voice present in at least half of the patients is stated to be caused by papillomata on the vocal cords.

Less frequent skin signs are hypertrichosis, either generalized or localized on the face, hyperhidrosis [Mori et al., 1996], multiple hemangiomata [Boente et al., 2001], hyperplastic nipples [Borochowitz et al., 1993; Tomita et al., 1998; Franceschini et al., 1999; Hori et al., 2000], supernumerary nipples [Borochowitz et al., 1993; Vila Torres et al., 1994], and mammary fibroadenosis [Costelo, 1996]. Three patients had unusual fat depositions [Berberich et al., 1991; Fryns et al., 1994; Czeizel and Tímár, 1995]. A cranial dermoid cyst [Di Rocco et al., 1993] and calcified epitheliomas [Martin and Jones, 1991] have also been reported.

INTERNAL ORGANS

Congenital heart defects are common in Costello syndrome. In particular, pulmonary valve stenosis, ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and atrial septal defects can occur. Mitral valve stenosis has also been round, but no aortic stenosis has yer been reported. Thickening of the intraventricular septum and clear-cut hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, usually of the subaortic region or septum, but sometimes the subpulmonic region, have frequently been found as well. The cardiomyopathy may be present at birth, or develop in the first year of life or at a later age. Usually it is symptomless and nonprogressive, but in at least one patient the course was fatal [Tomita et al., 1998], and in two others it had a significant impact on the patient's life [Fukao et al., 1996]. Dysrhythmias such as atrial ectopic tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation have been reported, both in patients with and in patients without a cardiomyopathy. It has even been detected during pregnancies [Flores-Nava et al., 2000].

Other internal organs are only infrequently involved in Costello syndrome. One patient was found to have a nephrotic syndrome [Suri and Garrett, 1998], another urolithiasis [Assadi et al., 1999], and still another a tracheo-esophageal fistula [Popa et al., 1996]. Cryptorchidism is commonly found (10%).

NEUROLOGY AND DEVELOPMENT

Neuroradiological studies do often show aspecific symptoms like enlarged ventricles or mild frontal atrophy. However, there have been reports of cerebellar atrophy [Zampino et al., 1993; Vila Torres et al., 1994; Mori et al., 1996], Chiari malformation [Say et al., 1993; Gripp et al., 2002], hydrocephaly needing shunting [Say et al., 1993; Zampino et al., 1993; Vila Torres et al., 1994], dysmyelinization of basal ganglia [Johnson et al., 1998], and hypodense white matter [Zampino et al., 1993; Johnson et al., 1998]. There are no long-term magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) follow-up studies. In a single patient, reduction in amplitude in visual evoked potentials and brain stem evoked potentials was reported [Patton and Baraitser, 1993], but in others normal results were reported. IQs have ranged from below 25 to 85, but usually are between 25 and 50. Most patients have a pleasant, happy, outgoing nature, but some were reported to be “apathic”, “nervous”, or “without smile” [Yoshida et al., 1993; Fukao et al., 1996; Popa et al., 1996], and to automutilate and have anxiety attacks [Van Eeghen et al., 1999]. Pubertal development has been reported to be delayed (somewhat) or complicated by primary [Van Eeghen et al., 1999] or secondary [Yetkin et al., 1998] amenorrhea.

GROWTH

Almost all patients have been large for theirages, but from birth on, weight gain is severely problematic. Hypothyroidism, either subclinical or symptomatic, and possible ACTH deficiency have been documented. In several patients, a partial growth hormone deficiency or low response in stimulation tests is present, and a favorable growth to growth hormone supplementation has been reported [Assadi et al., 1999; Gripp et al., 2000; Legault and Cagnon, 2001]. Adult height has varied from 116 cm, 118 cm, 140 cm, 147 cm, 148 cm, to 161 cm, respectively.

NATURAL HISTORY

Polyhydramnios is noted in about 60% of the patients. In one case, increased nuchal thickness was noted at sonography at 16 weeks of gestation [Kerr et al., 1998]. Delivery is frequently by cesarean section. Poor suck is universally noted. In a single patient, pyloric hypertrophy occurred [Johnson et al., 1998]. Somatic problems thereafter are significant but nonspecific, such as failure to thrive, upper airway infections, joint mobility problems, and strabismus, except for the increased risk for malignancies. Eleven patients have died, eight between 2 months to 27 months and two around 4 years because of a rhabdomyosarcoma [Gripp et al., 2002], and one at 32 years because of a schwannoma [Suri and Garrett, 1998].

MALIGNANCIES

Ganglioneuroblastoma (patients), bladder carcinoma (patients), acoustic neuroma (one), epitheliomata (one), neuroblastoma (one), and especially embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (10 patients) have been regarted [Gripp et al., 2002]. The rhabdomyosarcoma occurred mainly in the abdomen, pelvis, or urogenital area in infants and children between ½ to 6 years. The other tumors can occur both in children and adults. No abnormal reactions to therapy have been reported, and the prognosis was comparable to that of other children, without Costello syndrome, with a similar tumor; three children died because of the rhabdomyosarcoma.

The rhabdomyosarcoma occurred mainly in the abdomen, pelvis, or urogenital area in infants and children between ½ to 6 years. No abnormal reactions to therapy have been reported, and the prognosis was comparable to that of other children, without Costello syndrome, with a similar tumor.

This prompted Gripp et al. [2002] to suggest a tumor screening protocol consisting of abdominal and pelvic ultrasound examinations every 3–6 months from birth until 8–10 years, urinary catecholamine excretion measurements every 6–12 months until 5 years, and annual screening for hematuria from 10 years on. In a commentary however, DeBaun [2002] called attention to several points of criticism for any screening program for Costello syndrome, and urged for careful monitoring of these programs to determine their clinical usefulness. The relatively small number of patients will probably necessitate this monitoring to become international.

GENETICS AND PATHOGENESIS

Although affected sibs were reported [Berberich et al., 1991; Zampino et al., 1993; Johnson et al., 1998 (some sibs as Berberich et al., 1991)], all other examples have been isolated. Consanguinity was found only in patients originating from populations where consanguinity rate is high [Borochowitz et al., 1992; Franceschini et al., 1999]. In a careful analysis, Lurie [1994] concluded that Costello syndrome is caused by sporadic autosomal dominant mutations, the sib pairs representing gonadal mosaicism. Advanced paternal age has been demonstrated. A single chromosomal translocation [46,XX,t(1;22)(q25;q11)] associated with the condition has been reported [Czeizel and Tímár, 1995].

The conclusion is that Costello syndrome is probably an autosomal dominantly inherited entity of which almost all cases represent a spontaneous mutation, and of which at present the cause is unknown. The resemblance of Costello syndrome with cutis laxa and to a lesser extent Williams syndrome, the autopsy finding of fine, disrupted, and loosely constructed elastic fibers in the skin, tongue, pharynx, larynx, and upper esophagus (but not in bronchi, alveoli, aorta, or coronary arteries) [Mori et al., 1996], and the loss of anastomosing points in elastic tissue [Vila Torres et al., 1994], are in favor of disturbed elastogenesis.

The major component of extracellular elastic fibers is elastin, which is composed of cross-linked tropoelastin, and formed along a scaffold of microfibrils composed of different glycoproteins. Tropoelastin is guided intracellularly by elastin-binding protein (EBP), an enzymatically inactive variant of beta-galactosidase, which is also important in elastic fiber assembly [Hinek and Rabinovitch, 1994]. Elastic fiber formation may be disturbed either by a low production of tropoelastin, inadequate intracellular trafficking or release from the cell surface through inadequate functioning of EBP, and disturbed extracellular assembly either of the tropoelastin chains themselves or along the scaffold of microfibrils. A production defect of tropoelastin can be found in Williams syndrome, a deficient functioning of EBP is found in Hurler syndrome and other mucopolysaccharidoses, and an abnormal microfibrillar scaffold (i.e., fibrillin type 1) is known in Marfan syndrome.

In an excellent series of studies, Hinek et al. [2000] showed that cultured fibroblasts from Costello syndrome patients produce normal levels of tropoelastin, properly deposit the microfibrillar scaffold, but do not assemble elastic fibers by a deficiency of EBP. The deficiency of EBP was suggested to be secondary to an abnormal accumulation of chondroitin sulfate-bearing moieties, which leads to shedding of EBP from the cell surface instead of recycling and reuse [Hinek et al., 2000]. They also found an increased rate of proliferation of fibroblasts in Costello syndrome. Costello syndrome may thus be compared to the mucopolysaccharidoses. However, the fact that almost all mucopolysaccharidoses are autosomal recessively inherited and show progression in symptomatology, while Costello syndrome is autosomal dominantly inherited and not really progressive (including the essentially static cardiomyopathy) points against this, and points to a deficient functioning of a structural protein. This protein seems to be influenced by a maternal factor, taking into account the patients' increased cell growth prenatally and decreased cell growth postnatally. The lack of substantial changes in symptomatology after puberty makes a hormonal influence less likely. The earlier finding that the absence of insoluble elastin may increase cell proliferation [Li et al., 1998] may be important in explaining, the increased tumor rate in Costello syndrome.