Duty to warn at-risk relatives for genetic disease: Genetic counselors' clinical experience

Abstract

When a patient refuses to inform relatives of their risk for genetic disease, the genetic healthcare professional is faced with conflicting ethical obligations. On one side of the issue is the obligation to respect and protect patients' right to privacy. On the other side is the obligation to prevent harm and promote the welfare of the family members, which suggests a responsibility to warn at-risk relatives, even without the patient's consent. In an effort to examine the actual clinical impact of this issue, we conducted a pilot study that explored genetic counselors' experience with this conflict. A survey was developed and made available to members of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Questions were either multiple-choice responses or open-ended. Almost half of respondents (119/259; 46%) had had a patient refuse to notify an at-risk relative. The most commonly cited reasons for refusal were estranged family relationships, altering family dynamics, insurance discrimination, and employment discrimination, respectively. Of these 119 counselors, 24 (21%) reported that they seriously considered warning the at-risk relatives without patient consent, and one actually did disclose. Three factors consistently made the counselors less likely to disclose: their patient's potential emotional reaction, the relationship between the relative and patient, and the chance that the relative could be aware of the disease by another means. These results suggest that while the conflict is often encountered in clinical practice, it is rare that the situation remains unresolved to the extent that genetic counselors actually consider warning at-risk relatives. However, when the situation was encountered, the counselors in this study reported a lower rate of disclosure without consent than would have been anticipated based on previous studies that used hypothetical situations. It may be that counselors do not recognize a duty to warn at-risk relatives as integral to their role and professional obligations. © 2003 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Genetic research is rapidly identifying disease-related genetic mutations. These discoveries have led to the development of genetic testing in the clinical setting, which allows for the diagnosis of disease or the identification of the susceptibility for a particular condition. While such tests have clear benefits to clinical practice, they also bring difficult ethical issues to the forefront that are not seen with more traditional medical tests due to the unique characteristics of genetic testing [Skene, 1998]. One prominent distinguishing feature of genetic testing is that it reveals information not just about the individual undergoing the test, but also about that person's biologic relatives [Skene, 1998].

One prominent distinguishing feature of genetic testing is that it reveals information not just about the individual undergoing the test, but also about that person's biologic relatives.

In most cases, patients readily share this medically relevant information with their relatives. An ethical dilemma may arise, however, when a patient refuses to notify their relatives who are at-risk for carrying the same genetic mutation. Do these relatives have a right to the test results even if the patient getting tested does not want the information to be shared? When faced with such a situation, genetics professionals are met with conflicting ethical obligations. On the one hand, genetics professionals, like all healthcare professionals, are obligated to respect and protect their patient's right to privacy and to maintain confidentiality. In doing so, they limit the dissemination of medical information to abide by their patient's wishes [Berry, 1997]. On the other hand, healthcare professionals are also obligated to prevent harm and promote the welfare of others. This suggests a responsibility to breach patient confidentiality and warn at-risk family members [Pelias, 1991].

Historically, the importance of confidentiality in the physician-patient relationship is among the most basic tenets of medical ethics. It can be traced back to the Hippocratic oath, which implores physicians to act in their patient's best interests [Bok, 1983; Berry, 1997].

Historically, the importance of confidentiality in the physician-patient relationship is among the most basic tenets of medical ethics. It can be traced back to the Hippocratic oath, which implores physicians to act in their patient's best interests.

It was thought that without the promise of confidentiality, patients would be reticent to share information that might be embarrassing or stigmatizing but medically important [Kottow, 1986; Berry, 1997]. Without having all potentially useful or contributory information, physicians' ability to provide the most effective treatment might be hindered. Therefore, confidentiality was paramount to patients' procurement and physicians' provision of optimal medical care. More recently, the concept of confidentiality became defined in the context of patient rights. The U.S. Constitution protects the right to privacy, which extends to personal medical information [Bok, 1983; Stepanuk, 1998]. In this context, physicians have a legal duty to protect their patient's medical information. Furthermore, as with any such obligation, healthcare providers who fail to fulfill this responsibility can face legal action [Knoppers, 1991; Pelias, 1991].

The legal duty to maintain confidentiality of patient information, however, is not absolute. Traditionally, disclosure of a patient's medical information without their consent is permitted or even expected in a limited number of clinical situations, including cases of suspected abuse, infectious disease, gunshot wounds, or if the patient is deemed an immediate threat to themselves or society. It was this last reason that was cited in the landmark case of Tarasoff v. the Regents of the University of California [1976; Suter, 1993], in which the California Supreme Court ruled against a psychiatrist who did not warn a third party of his patient's harmful intent. The court found that the risk of harm to the third party outweighed the right of patient confidentiality, and that the psychiatrist had a duty to warn that third party. By this ruling, physicians were mandated to warn third parties of immediate potential harm from their patients, even if such warning broke patient confidentiality [Petrilla, 2001].

How this legal duty to warn applies to genetics professionals is not at all clear. To date, the legal precedent has been established by two cases, with each leaving considerable uncertainty over what circumstances create a duty to warn, and how that responsibility can be discharged. In Pate v. Threkel, the Florida Supreme Court ruled against a physician who neglected to warn family members of the risk that an inheritable form of cancer might be passed on to children [Deftos, 1998]. However, the ruling stated that had the physician notified the patient of the genetic risk to his children, this duty would have been fulfilled as one could reasonably expect the patient to disseminate the necessary information. In Safer v. Pack, the New Jersey Supreme Court also agreed that the physician had a duty to warn the relatives of his patient, but stated that this duty may not necessarily be satisfied by only notifying patients of their relatives' risk and expecting the patients subsequently to disseminate the information. The court recognized that physicians may need to resolve a conflict between their broader duty to warn and their protection of patient confidentiality [Pretzer, 1997; Petrilla, 2001]. Unfortunately, based on these rulings, it is not clear what responsibility genetics professionals have to at-risk relatives of their patients, and how that responsibility should be discharged [Petrilla, 2001].

While the legal system has not provided a clear statutory ruling on the responsibility to at-risk relatives, several professional organizations have attempted to address this issue. In 1983, the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine published guidelines citing four conditions that should be met before patient information is disclosed without consent [Juengst, 1997]: when reasonable efforts to elicit voluntary consent to disclosure have failed; there is a high probability that harm will occur if the information is withheld and that the disclosed information will actually be used to avert harm; the harm that identifiable individuals would suffer would be serious; and appropriate precautions are taken to ensure that only the genetic information needed for diagnosis and/or treatment of the disease in question is disclosed.

Similarly, the American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG) published their own recommendations in 1998 that address the duty of genetics professionals to at-risk family members: “Genetic information, like all medical information, should be protected by the legal and ethical principle of confidentiality. Disclosure should be permissible where attempts to encourage disclosure on the part of the patient have failed; where the harm is highly likely to occur and is serious and foreseeable; where the at-risk relative(s) is identifiable; and where either the disease is preventable, treatable, or medically accepted standards indicate that early monitoring will reduce the genetic risk. The harm that may result from failure to disclose should outweigh the harm that may result from disclosure. At a minimum, health-care professionals should be obliged to inform patients about the implications of their genetic test results and about the potential risks to their family member” [American Society of Human Genetics Social Issues Subcommittee on Familial Disclosure, 1998].

The National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) has not published specific recommendations, but does have a general position statement that “supports an individual's right to privacy and confidentiality regarding genetic information, including the results of genetic testing” (position statement adopted in 1991, revised in 2002; available at http://www.nsgc.org/about_position.asp).

While these guidelines outline some of the essential factors that should be considered, they leave room for subjective interpretation for the practicing genetics professional faced with this situation. For example, what is meant by “attempts to encourage reasonable disclosure”? Are phone calls enough, and if so how many? And how or by whom is the relative magnitude of harm determined?

To date, there has been little investigation into how genetics professionals view this complicated issue. Published studies addressing this question have used hypothetical situations to predict how a genetics professional might act in a given situation. Wertz and Fletcher [1988] found that 54% and 53% of medical geneticists predicted they would inform relatives of their risk in cases involving patients with hemophilia A and Huntington disease, respectively. As justification, 37% cited the relative's right to know, 22% cited duty to warn, and 19% cited reproductive planning [Wertz and Fletcher, 1988]. However, nearly half indicated that they would not disclose patient information without consent in deference to protecting patient's privacy, and the relative's right not to know [Wertz and Fletcher, 1988]. In similar studies using hypothetical situations, genetic counselors were less likely to disclose than medical geneticists [Pencarinha et al., 1992]. Moreover, in Geller et al. [1993], medical geneticists and genetic counselors predicted less disclosure without consent than did physicians of other specialties.

While these hypothetical studies are valuable, they may not reflect how a clinical geneticist or genetic counselor actually does act when faced with this situation in their practice. In a clinical situation, a patient's individual circumstances always influence a clinician's assessment of the potential consequences of disclosure. This added level of complexity might result in different actions than could be predicted in hypothetical scenarios. In an initial effort to investigate this question, we conducted a survey-based study of NSGC members on their understanding of and experience with disclosure of genetic information to at-risk relatives without patient consent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A questionnaire was made available to an estimated 1,000 members of the National Society of Genetic Counselors listserv. The questionnaire (available on request) consisted of five sections, each containing multiple-choice, yes/no, and open-ended questions. Section 1 contained general questions on the duty of genetic counselors to warn at-risk relatives, including knowledge about published guidelines and recommendations. Section 2 asked about the genetic counselor's experience with patients who had refused to notify at-risk relatives, including describing the frequency of this occurring in their practice and patients' reasoning for refusing to disclose. Section 3 focused on those who had seriously considered warning the at-risk relative of a patient without that patient's consent. It included questions on the circumstances of the particular case(s), and what factors went into the decision whether or not to disclose the information. Section 4 asked similar questions of those counselors who had gone on to warn a relative without consent. Demographics were obtained in section 5.

Genetic counselors were invited to participate in the study via the NSGC listserv, which has approximately 1,000 subscribers. (It is unclear how many genetic counselors actually access the main section of the listserv, where the e-mail was posted. Therefore, it is impossible to estimate accurately the number of genetic counselors who were actually invited to participate.) Individuals completed the survey on the Internet and returned the survey using the computer program Response-o-matic, which automatically removes all identifying information from the completed questionnaire. In addition, written copies of the survey could be picked up during the 19th NSGC Educational Conference in Savannah, Georgia, in November 2000. The study was conducted with approval of the institutional review board of the University Hospitals of Cleveland.

RESULTS

A total of 259 completed questionnaires were returned, with the majority (222/257) coming through the Internet. It is worth noting that we found no demographic differences between those who completed the questionnaire via the Internet and those who completed it at the NSGC meeting. Most participants worked in academic settings (56%) or community hospitals (19%). All but 19 (8%) were actively involved in clinical care, and these 19 individuals reported that they had seen patients in the past. Prenatal genetics was the most common primary practice setting (45%; 117/259), followed by pediatric (12%; 32/259) and cancer genetics (12%; 31/259; the total number of respondents varies throughout due to nonresponders to some questions). Additional demographic information is provided in Table I.

| Primary responsibility | ||

| Prenatal genetics | 117/259 | (45%) |

| Pediatric/general | 45/259 | (17%) |

| Cancer genetics | 31/259 | (12%) |

| Research | 18/259 | (7%) |

| Other | 35/259 | (13%) |

| Setting | ||

| Academic medical center | 144/259 | (56%) |

| Community hospital | 50/259 | (19%) |

| Other | 51/259 | (20%) |

| Do genetic counselors have an obligation to at-risk relatives (yes)? | 161/257 | (63%) |

| Would you disclose without consent | ||

| When no medical benefit exists? | 0/258 | (0%) |

| When risk of disease to the relative is high? | 19/258 | (7%) |

| When lifestyle changes may alter risk? | 19/257 | (7%) |

| When early monitoring may be beneficial? | 20/257 | (8%) |

| When there are reproductive choices? | 13/256 | (5%) |

| Are you aware of | ||

| Any federal or state laws? | 61/253 | (24%) |

| ASHG guidelines? | 111/253 | (44%) |

| NSGC guidelines? | 89/254 | (35%) |

| Other published guidelines? | 19/251 | (8%) |

| Your institutional policy? | 47/257 | (18%) |

| How often have you encouraged patients to inform their at-risk relatives? | ||

| Always | 156/259 | (60%) |

| Often | 88/259 | (34%) |

| Rarely | 7/259 | (3%) |

| Never | 1/259 | (0%) |

| Have you ever had a patient refuse to notify an at-risk relative (yes)? | 115/250 | (46%) |

| How many times? | Average, 4; range, 1–30 | |

| Seriously considered notifying without consent (yes)? | 22/119 | (18%) |

| How many times? | ||

| 1 | 13/22 | (59%) |

| 2 | 4/22 | (18%) |

| 3 | 5/22 | (9%) |

| >3 | 3/22 | (15%) |

| Factors making participants less likely to warn at-risk relatives | Did consider | Less likely to warn |

| Patients' emotional reaction | 24/30 (80%) | 17/20 (85%) |

| Patient and relatives' emotional relationship | 23/29 (79%) | 9/16 (56%) |

| Likelihood relative may know by another means | 19/29 (66%) | 10/17 (58%) |

| Factors making participants more likely to warn at-risk relatives | Did consider | More likely to warn |

| Magnitude of risk for the relatives | 28/29 (97%) | 20/24 (83%) |

| If the condition is treatable/manageable | 25/30 (83%) | 16/20 (80%) |

| Whether early monitoring can alter risk | 16/28 (57%) | 10/13 (77%) |

| Resources utilized when considering notifying | ||

| Colleagues | 26/26 | (100%) |

| Formal case conference | 11/26 | (42%) |

| Legal consultant | 6/26 | (23%) |

| Social worker | 4/26 | (15%) |

| Institutional ethic committee | 3/26 | (12%) |

| Published guidelines | 3/26 | (12%) |

| Institutional review board | 1/26 | (4%) |

The majority of participants (63%; 161/257) believed that genetic counselors do have an obligation to share genetic information with their patient's relatives. However, in responding to several theoretical scenarios, only a small minority felt that they would in fact disclose.

The majority of participants believed that genetic counselors do have an obligation to share genetic information with their patient's relatives. However, in responding to several theoretical scenarios, only a small minority felt that they would in fact disclose.

For example, 7% (19/257) responded that they would disclose if the risk to the relative was high or if lifestyle changes would alter that risk, 8% (20/257) if early monitoring would be beneficial, and 5% (13/257) if the information might alter reproductive choices.

When questioned about existing laws and guidelines, 24% (61/253) of the respondents falsely believed that there were federal guidelines that regulated disclosure. Almost half (44%; 111/253) were aware of the ASHG guidelines, but 35% (89/254) incorrectly thought that the NSGC had specific guidelines for this issue. Lastly, 47/257 (18%) reported that they had been informed about specific institutional policies. Of the 46 who described these policies, 38 (83%) indicated that their institution's policy was not to disclose patients' genetic information to anyone without the consent of the patient.

When asked whether they encouraged patients to inform their at-risk relatives, 156/252 (62%) stated “always” and 88/252 (35%) stated “often.” The vast majority of respondents (82%; 205/250) reported having a patient express concern about notifying an at-risk relative, and almost half (46%; 119/259) stated that they have had a patient refuse to notify. The most commonly cited reasons for refusal were estranged family relationships, concern for altering family dynamics, insurance discrimination, and employment discrimination. Other reasons cited by the participants included guilt, shame, and embarrassment, that the risk to relatives was not high enough or relevant, protecting own (patient's) privacy, not wanting to worry relatives, and that the patients were “too lazy” or did not want to take the time to inform relatives.

Of the 119 genetic counselors who had a patient refuse to notify an at-risk relative, 21% (25/119) reported having seriously considered warning the relative without their patient's consent. Nineteen of these 25 respondents described a total of 24 situations. These

When asked whether they encouraged patients to inform their at-risk relatives, 62% stated “always” and 35% stated “often.” The vast majority of respondents reported having a patient express concern about notifying an at-risk relative, and almost half stated that they have had a patient refuse to notify.

clinical cases were categorized as familial translocations (10), familial cancer mutations (5), fragile X syndrome pre- or full-mutation carriers (3), Huntington disease (2), and 4 involved a specific genetic syndrome.

The 25 respondents where asked whether they considered various circumstances when deciding whether to warn at-risk relatives (Table II). Three circumstances consistently made participants less likely to warn at-risk relatives: the patient's emotional reaction (considered by 24/30; 80%), with 17/20 (85%) stating that this made them less likely to warn at-risk relatives; the patient and the relative's emotional relationship (23/29; 79%), which made 9/16 less likely to warn at-risk relatives; and the likelihood that the relative may know about the condition by another means (19/29; 66%), which made 10/17 (59%) less likely to warn the at-risk relatives. Several medical factors consistently made genetic counselors more likely to warn at-risk relatives, including magnitude of risk and whether the risk could be altered by some action. Nearly all respondents considered the magnitude of the risk (28/29; 97%), making 20/24 (83%) more likely to warn.

| % considered | (% more/less likely)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Magnitude of risk to relative | 97 | (83/17) |

| Rx/management available | 83 | (80/20) |

| Patient's emotional reaction | 80 | (15/85) |

| Relationship and patient's emotional relationship | 79 | (44/56) |

| Biologic relationship | 77 | (89/11) |

| Relative is aware of risk by other means | 66 | (41/59) |

| Age of relative | 57 | (77/23) |

| Early monitoring | 57 | (77/23) |

| Lifestyle changes | 50 | (75/25) |

| Age of patient | 30 | (50/50) |

- a % considered refers to the percent of counselors who considered this factor. The second set of figures refers to the number for which considering this factor made the counselor more or less likely to disclose.

The 25 respondents utilized a variety of resources when deciding if they should warn at-risk relatives. These included consulting colleagues (100%), formal case conferences (42%), lawyer (23%), social worker (15%), institutional ethics committee (12%), published guidelines (12%), and an institutional review board (4%).

Of these 25 respondents who had seriously considered warning at-risk relatives, 24 did not breech confidentiality and go contact the at-risk relative. When asked why, the responses could be categorized by theme: respect for patient confidentiality; this action was outside the genetic counselor's role; legal liability; and the case was eventually resolved. One genetic counselor did go on to warn the at-risk relative without consent, although the clinical situation was somewhat unusual. The relative was also a patient of the genetic counselor, and the first patient's negative test results were shared to prevent unnecessary invasive testing for the relative. There were several unsuccessful attempts made to contact the first patient to obtain permission to share the test results with the sibling.

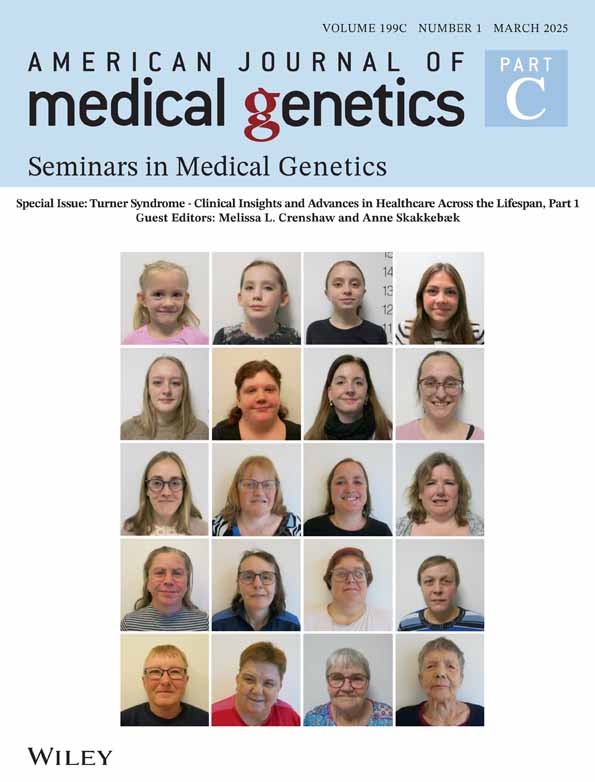

The responses were further analyzed by comparing respondents from three groups (Fig. 1). Group 1 consisted of 140 participants (140/259; 54%) who never had a patient refuse to notify at-risk relatives; group 2 (94/259; 36%) had a patient refuse to notify relatives but never seriously considered warning the at-risk relatives; and group 3 (25/259; 10%) had seriously considered warning at-risk relatives. While there were no statistically significant differences between groups, there were some interesting trends noted, in that genetic counselors who had seriously considered warning at-risk relatives (group 3) were more likely to feel that counselors had an obligation to at-risk relatives (75% vs. 54% of group 2 vs. 66% of group 1) and tended to encourage their patients to inform at-risk relatives (71% vs. 64% of group 2 vs. 56% of group 1).

Breakdown of respondents.

DISCUSSION

The results of this preliminary study suggest that genetic counselors often encounter situations in clinical practice in which there is a potential conflict between patient confidentiality and a duty to warn at-risk relatives. Over 80% (205/252) of the respondents stated that they had patients express concern with discussing genetic test results with an at-risk relative, and almost half (46%; 119/259) reported that they had a patient refuse to share such information with at-risk relatives one or more times. However, only a small number of this group (21%; 25/119) seriously considered breaching confidentiality by notifying the at-risk relatives without the explicit consent of their patient, and only one actually did go on to disclose without consent.

These results suggest that genetic counselors do not warn at-risk relatives as frequently as would have been predicted based on the previous studies that used hypothetical situations [Wertz and Fletcher, 1988; Pencarinha et al., 1992]. Why did the genetic counselors report a relatively low rate of disclosure without consent in their clinical practice? There are several possible and perhaps overlapping explanations.

Genetic counselors are trained to be nondirective, to allow their patients to make their own independent decisions based on the information conveyed in the genetic counseling process. In that regard, a primary goal of genetic counseling is to respect the patients' autonomy concerning their own medical issues, including genetic test results [National Society of Genetic Counselors, 1992]. That the genetic counselors in this study chose to maintain confidentiality of their patients and not disclose the information to at-risk relatives is consistent with these principles of genetic counseling. When faced with this conflict, genetic counselors prioritized their patient's autonomy over other ethical obligations. While genetic counselors in this study did acknowledge a responsibility to at-risk relatives, they viewed the act of disclosing without consent as outside their responsibility.

It may be that genetic counselors do not appreciate circumstances that warrant disclosure without consent. The majority (63%) of respondents stated that genetic counselors do have an obligation to at-risk relative. However, very few stated that they would disclose without consent. For example, 7% would disclose if the risk was relatively high to the relative, if lifestyle changes would alter the risk (7%), if early monitoring was beneficial (8%), and/or if the information would alter reproductive risks (5%). It is interesting to note that these are circumstances that are outlined in the ASHG guidelines [American Society of Human Genetics Social Issues Subcommittee on Familial Disclosure, 1998], by which it may be permissible to breach confidentiality. This suggests and is supported by the findings of this study that most respondents were not familiar with established guidelines and recommendations.

While the differences between groups did not reach statistical significance, another interesting trend noted was that a higher percentage of the genetic counselors who seriously considered warning at-risk relatives (group 3) were less aware of the ASHG guidelines compared to the group as a whole (66% vs. 54%). However, a greater proportion of these respondents felt counselors had an obligation to patients' at-risk relatives (75% vs. 53%). From the opposite viewpoint, perhaps those genetic counselors who were more familiar with the ASHG guidelines and NSGC code of ethics felt less obligated to warn at-risk relatives as the guidelines do not provide a specific mandate to do so.

Finally, it is possible that the relatively low disclosure rate as compared to that seen in Wertz and Fletcher [1988] and Pencarinha et al. [1992] was due to resolution of many of the cases before the genetic counselor was forced to disclose. The ASHG guidelines emphasize that every effort must be made to facilitate having the patient consent to sharing the information before breaching confidentiality [American Society of Human Genetics Social Issues Subcommittee on Familial Disclosure, 1998]. It may be that, in real clinical situations, most patients eventually agree to share the information with their at-risk relatives. This is consistent with the clinical experience of the authors (A.L.M., G.L.W., N.H.R.). Obviously, resolution could not be represented in the theoretical studies [Wertz and Fletcher, 1988; Pencarinha et al., 1992].

When asked what factors they considered when deciding whether or not to disclose to the at-risk relatives, the participants cited emotional factors as being very important. The patient's reaction and the relationship of the patient and relative were factors that made the majority of these counselors less likely to warn at-risk relatives. The influence of these emotional factors is absent from hypothetical studies (e.g., Wertz [2000]). It may be that their presence in the counseling setting is one element that explains the differences between those studies proposing hypothetical scenarios and the results of this study.

There are several limitations to this study. First, we are unable to determine an accurate response rate. While the survey was made available to approximately 1,000 NSGC listserv members as well as left for attendees to pick up on their own at the educational meeting, we were unable to monitor exactly how many NSGC members had the opportunity to respond and decided not to participate. If one considers the denominator to be 1,000 (the approximate number of genetic counselors on the listserv), then the response rate is approximately 25%. However, we have no way of knowing how many actually received the e-mail notification for the survey, and how many did and chose not to respond. Furthermore, in an effort to increase our response number, we made the survey available at the NSGC national meeting. There were several hundred attendees at this meeting, but only a small fraction may have seen the survey, many of whom may have already responded by e-mail. To prevent duplicate responses, the written survey contained instructions that stated not to complete the questionnaire if they had responded by e-mail. We used this approach to maximize the response number. However, we still are unable to establish an accurate number for the total number of people who chose not to respond to the survey.

The inability to determine an accurate response rate for Internet-based studies has been has discussed [Titus et al., 2000]. This limitation is considered acceptable for studies in which a self-selection bias can be tolerated. Such was the case with this study, as we sought to obtain information from genetic counselors who encountered this dilemma. We recognize that these results cannot be generalized to all genetic counselors, but rather reflect the experience of this select group with this issue.

Because of the difficulty in determining a response rate, most studies that utilized an Internet-based survey do not report a response rate [Barash et al., 2001; Branda et al., 2001; Wahl et al., 2001]. However, our estimated response rate of 25% does compare favorably with those that do. For example, Petrucelli et al. [2001] surveyed 295 eligible members of the NSGC cancer listserv and reported a 19.3% response rate.

It is uncertain if utilizing the Internet format as an avenue to distribute surveys is an ideal methodological approach. Do listserv members tend to disregard such surveys more than they would a mailed survey, or does it generate a higher response rate? Further study of this methodology is clearly needed.

Secondly, as with any study that inquires about past experience, the responses are subject to recall bias. Participants may have only recalled cases that were particularly difficult or stood out in some way such that the counselor remembered the case. Thus, the actual number of cases where the conflict of breaking confidentiality and duty to warn at-risk relatives might actually be higher than that reported by participants. Moreover, NSGC listserv members might not have responded to the Internet survey as they were concerned about maintaining patient confidentiality of a specific case and felt that they could not adequately conceal a patient's identity or circumstances. However, it may be possible in future studies to conduct a prospective study utilizing a comparison group. The questionnaire contained mostly multiple-choice and yes/no questions that may have artificially limited some responses. In an effort to minimize this, a number of open-ended questions were included with instructions to respondents to provide additional information or details if they desired. Lastly, we did not investigate the clinical circumstances around each individual case as presented by the 24 respondents who seriously considered warning at-risk relatives without patient consent. Perhaps we might have been able to define some trends among this group if information about disease severity or inheritance had been available for comparison.

For these reasons, the data presented here should be viewed as a first step in better defining the questions that could to be addressed in future studies. While not generalizable beyond the numbers presented in this study, these data for 257 respondents do provide some indication of trends concerning genetic counselors' practices regarding duty to warn. The results of this study suggest that genetic counselors prioritize patient autonomy over other ethical obligations. Future studies should look to build on the results generated to examine why this may be the case. For example, is the nature of genetic counselor education and training such that counselors put patient advocacy and confidentiality as priorities, or do specific patient situations and interactions guide the counselor's clinical practice regarding confidentiality? If it is a direct result of education, are there differences among different training programs? If this attitude is developed through experience gained in clinical practice, does the type of clinical practice (prenatal, cancer, general) or the setting (academic center, community hospital) have a significant influence? We did not find any differences among these factors, but our survey did not focus on these areas. These would be important topics to explore in future studies on genetic counselors.

A second interesting area for further research would be to examine the experiences of both genetic and nongenetic medical professionals with this issue. In an international study to investigate trends in practice behavior among genetics and nongenetics professionals in 37 countries, Wertz [1997] found that culture and professional training had a greater influence than gender on practice. Given these results, it would be especially interesting to compare genetic counselors with genetic and nongenetic medical professionals by professional training and by gender to see if the observations of Wertz [1997] are supported by actual clinical practice in this controversial issue.

It will be particularly important to include nongenetics physicians in these future investigations. Studies have shown that these physicians have a more limited understanding of the implications of genetic testing [Robin et al., 2001; Sandhaus et al., 2001]. As it is most likely that in the future primary care physicians will be ordering most genetic tests, knowing the extent and limitations of their experience with this issue will be very important in educating them regarding genetic testing.

As the number of genetic testing continues to increase, situations like those described here will only increase in frequency. Genetic counselors, geneticists, and nongenetics healthcare professionals will need to understand their responsibilities to their patients and to their patient's at-risk family members. However, as was shown in this study, a significant percentage of genetic counselors were not familiar with the limited guidelines and how they pertained to a given situation. This reinforces the need for comprehensive guidelines to be developed for clinical conduct that balances the rights of the patient and the responsibility to warn at-risk relatives.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Society of Genetic Counselors for their cooperation with this project, and Michael Dugan for his assistance in creating the Web-based questionnaire.