A longitudinal characterization of the adaptive and behavioral profile in Sotos syndrome

Abstract

Delineation of a developmental and behavioral trajectory is a key-topic in the context of a genetic syndrome. Short- and long-term implications concerning school outcome, independent living, and working opportunities are strictly linked to the cognitive and behavioral profile of an individual. For the first time, we present a longitudinal characterization of the adaptive and behavioral profile of a pediatric sample of 32 individuals with Sotos Syndrome (SoS) (18 males, 14 females; mean age 9.7 ± 4 years, eight carrying the NSD1 5q35 microdeletion and 24 with an intragenic mutation). We performed two clinical assessments: at baseline (T0) and at distance evaluation (T1) of adaptive and behavioral skills with a mean distance of 1.56 ± 0.95 years among timepoints. Our study reports a stability over the years—meant as lack of statistically significant clinical worsening or improvement—of both adaptive and behavioral skills investigated, regardless the level of Intellectual Quotient and chronological age at baseline. However, participants who did not discontinue intervention among T0 and T1, were characterized by a better clinical profile in terms of adaptive skills and behavioral profile at distance, emphasizing that uninterrupted intervention positively contributes to the developmental trajectory.

1 INTRODUCTION

Sotos syndrome (SoS) is a rare (1:14,000) autosomal dominant congenital overgrowth syndrome (OMIM #117550). Most individuals (about 90%) with SoS are genetically connoted by abnormalities of the transcription factor “Nuclear receptor binding SET Domain protein1” (NSD1) gene (Kurotaki et al., 2002; Tatton-Brown al., 2005). Several genetic alterations can abolish NSD1 gene function (i.e., small intragenic mutations like deletions/insertions, nonsense/missense pathogenic variants, partial gene deletions and whole deletions or the microdeletion of 5q35 chromosomal region) with 5q35 microdeletion representing the most frequent genetic aberration in the Japanese population (90%) but not in other countries (10%–20%) (Douglas et al., 2003; Novara et al., 2014;Tatton-Brown et al., 2005; Tatton-Brown et al., 2005). SoS syndrome is clinically characterized by multiple organic malformations (cardiac, genitourinary, scoliosis), seizures, and increased risk of tumors (Tatton-Brown et al., 2005; Tatton-Brown et al., 2005). It is usually caused by de novo pathogenic variants (Tatton-Brown et al., 2005; Testa et al., 2023).

Recommended surveillance for an individual with SoS includes echocardiogram, renal ultrasound examination, ophthalmologic exam, audiologic assessment, brain MRI (Tatton-Brown et al., 2004; Tatton-Brown & Rahman, 2007). Regular evaluation is performed by a general pediatrician, but depending on their clinical needs, individuals with wider complications require a stronger medical support and will need to be subject to recurring instrumental examinations. Thus, parents of SoS children must face multiple challenges connected to medical issues. This context prompts the need to define possible positive or negative predictors of developmental and behavioral outcomes.

A SoS-specific cognitive and behavioral profile is still under definition, but a wide range of intellectual functioning and behavioral problems (internalizing: anxiety, withdrawn; externalizing: hyperactivity, disattention) seems to depict a common phenotype of this syndrome (Lane et al., 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019; Siracusano et al., 2023). Particularly, a genotype–phenotype correlation, which includes cognitive and behavioral skills, has not been clearly defined yet (de Boer et al., 2006; Novara et al., 2014; Tatton-Brown et al., 2005). However, our research team has recently suggested that the 5q35 microdeletion is associated with lower scores in cognitive, adaptive (child's skills level of independence in social and practical activities), and behavioral domains (Siracusano et al., 2023).

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study provided a longitudinal definition of the cognitive and behavioral phenotype of SoS individuals.

As a matter of fact, in the context of genetic syndromes, a key topic is not only the definition of a cognitive behavioral profile but also the delineation of a specific trajectory of its clinical issues. Identifying possible negative and predictive factors could support the clinician to answer critical parental questions concerning child's future in terms of school outcome, independent living, and working opportunities. What is more important, it could also help address the intervention pointing at appropriate and tailored objectives.

Starting from the literature's limits and given our research background on the characterization of the neuropsychological profile within SoS children, we performed this study aiming to longitudinally evaluate the adaptive and behavioral profile of a sample of individuals with SoS.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

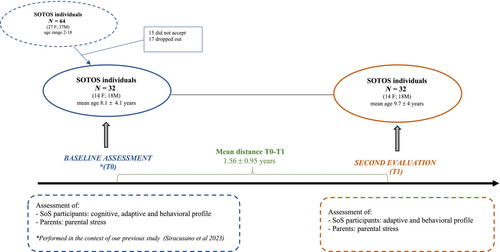

The population of this observational study is constituted by SoS individuals included in a previous project run by our research team (Siracusano et al., 2023). All previously enrolled participants—who still continue to be assisted by our Unit—were asked, over the years, to undergo a second evaluation to depict their clinical evolution, by longitudinally characterizing their adaptive skills and behavioral features (internalizing, externalizing symptoms). For the purpose of the present study, we considered the evaluation performed during our previous work (Siracusano et al., 2023) as the baseline assessment (T0); whereas the follow-up assessment provided at distance represents the T1 (Figure 1).

At T0 and T1, detailed information concerning intervention (type, duration, frequency) was collected via a parental interview. The range between T0 and T1 was not pre-established but reflects the clinical needs of each SoS participant.

All SoS individuals taken in charge by our Unit, were prescribed an intervention at T0 and T1 according to their clinical needs (i.e., speech therapy, cognitive behavioral intervention, and/or physiotherapy). However, our Unit mainly provides diagnosis and follow-up visits, thus intervention is not a provided service. SoS individuals are taken in charge by rehabilitation centers after our clinical assessment. Nevertheless, not all individuals performed the intervention prescribed due to several motives (e.g., costs of the intervention, difficulty in reaching the rehabilitation center). For all such reasons, we observed two groups of participants: individuals who regularly underwent the prescribed intervention, others who did not, and others still who discontinued the treatment between T0 and T1. It is necessary to specify that discontinuing the treatment or not wasn't a choice of the clinical researchers, but a family decision.

The intervention between baseline and follow-up is detailed in Table 1. Specifically, Table 1 reports the number of individuals attending specific treatments at each timepoint, categorized into four groups: speech therapy or physiotherapy, behavioral intervention, mixed intervention (speech therapy and physiotherapy, behavioral intervention), and other treatments (e.g., psychoeducational).

| T0 | T1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of intervention | (N) | (N) |

| Speech therapy or physiotherapy | 14 | 9 |

| Cognitive-behavioral | 3 | 6 |

| Mixed therapy (Cognitive-Behavioral + speech therapy/physiotherapy | 5 | 6 |

| Other | 6 | 7 |

- Note: The table reports number of individuals attending specific interventions at each timepoint, categorized in 4 groups: speech therapy or physiotherapy, behavioral intervention, mixed intervention (speech therapy and physiotherapy, behavioral intervention) and other treatments (i.e., psychoeducational).

Given the wide variety of interventions, for the purpose of this study, we divided participants into two groups: Uninterrupted Intervention Group, including participants attending an intervention (independently from the type of treatment) during the whole period between T0 and T1; Discontinuous Intervention Group, including individuals who did not undergo therapy or discontinued it between T0 and T1.

2.1 Sample enrollment

From the sample of 64 SoS individuals enrolled for a previous project (Siracusano et al., 2023), 15 did not accept to participate (were not interested in a second evaluation); 17 dropped out due to difficulties in reaching the Tor Vergata Hospital (they lived far away from the research site).

All participants underwent the genetic analyses described above to categorize the NSD1 gene aberrations: intragenic mutations (frameshift, nonsense, missense, splice site, partial gene deletions) or 5q35 microdeletion (Table 2).

| Category and types of NSD1 aberrations | Number of SoS individuals | |

|---|---|---|

| Intragenic mutations | Frameshift | 11 |

| Nonsense | 4 | |

| Missense | 5 | |

| Splice site | 2 | |

| Partial gene deletions | 2 | |

| 5q35 microdeletion | 8 | |

- Note: Number of SoS individuals grouped considering the type of NSD1 gene aberration: intragenic mutations (frameshift, nonsense, missense, splice site, partial gene deletions) or 5q35 microdeletion.

This study has been conducted in collaboration with the Italian Association of Sotos Syndrome (ASSI Gulliver). The study protocol has been approved by the Ethical Committees of Rome Tor Vergata University Hospital (#6022) and has been performed in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all parents/guardians of the participants.

2.2 Genetic analyses

Genomic DNA was obtained from peripheral blood cells, using DNA mini extraction kit (Qiagen). In order to identify microdeletions of band 5q35.3 we performed Array-CGH analysis using Sureprint G3 Human CGH Microarray Kit 8×60k (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturers' protocol. Data were analyzed by Agilent cytogenomics 4.0.3.12 software (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All genomic positions were reported according to the human genome assembly (GRCh37/hg19). PCR amplification was performed using primers specific for the different 23 NSD1 exons as previously described (Conteduca et al., 2023). Briefly, Purified PCR products were sequenced with the ABI Big Dye terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI Prism 3730 automatic DNA sequence (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Sequences were aligned with Seqscape analysis software V.2.5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

2.3 Evaluation at baseline (T0)

The baseline evaluation (Siracusano et al., 2023) included a standardized assessment of cognitive skills (Intellectual Quotient-IQ), adaptive functioning, and behavioral issues (internalizing, externalizing symptoms) through the below reported instruments.

2.3.1 Cognitive evaluation

“Leiter international performance scale revised (Leiter-R).”

The Leiter-R (Roid & Miller, 1997) provides a measure of nonverbal cognitive abilities in children and adolescents aged from 2 to 20 years. This scale is suitable for individuals with communication and language difficulties and scarce level of cooperation, permitting to estimate the child's intellectual functioning without being negatively impacted by language or cooperation difficulties.

For this reason, it is widely employed for the cognitive assessment of children with neurodevelopmental disorders, including those with Autism Spectrum Disorder. The Leiter-R provides a standardized nonverbal Brief-IQ score which includes four subtests [figure ground (FG), form completion (FC), sequential order (SO), and repetitive pattern (RP)] of the visualization and reasoning (VR) battery domains. Raw scores are converted in scaled and finally in composite score, having a population mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15.

2.3.2 Adaptive skills assessment

“Adaptive Behavior Assessment System second edition (ABAS-II).”

The Adaptive Behavior Assessment System-second edition (ABAS-II) (Oakland, 2011) is a parent-report questionnaire which provides a measure of the child's adaptive functioning—child's skills level of independence—including developmental, behavioral, and cognitive skill areas. According to the participants' age, the “0–5 years” or “5–21 years” form was administered. Parents are asked to rate their child behavior on a 4 points Likert Scale (from 0 = “not able to” to 3 = “able to do it and always performs it when needed”) in relation to 10 fields (i.e., communication, use of environment, preschool competences, domestic behavior, health and safety, play, self-care, self-control, social abilities, and motility), which are in turn organized in three main domains: (1) conceptual (CAD); (2) practical (PAD); (3) social (SAD). Moreover, a General Adaptive Composite (GAC) score is provided by the sum of scaled scores from all the skills domains. Composite scores have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15.

2.3.3 Behavioral assessment

Children's behavior, including emotional symptoms and internalizing (defined as negative mood and behaviors focused inward) externalizing (defined as negative, acting-out behaviors characterized by lack of self-control) behavioral problems, was assessed using parent report measures described below.

2.4 Child behavior checklist (CBCL)

Children's and adolescents' behavioral difficulties were assessed through the parent report measure Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000).

Two forms are available depending on the child's age: the “18 months–5 years” and the “6–18 years” form. Both scales provide three main score domains: Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms and Total Behavior. In addition, each age form is structured in different Syndrome Scales (the “18 months–5 years”: Emotionally Reactive, Anxious/ Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Withdrawn, Sleep Problems, Attention Problems, Aggressive Behavior; the “6–18 years”: Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Rule-Breaking Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior). Adverse behavior is rated by parents on a 3 points Likert Scale (0 = not true, 1 = sometimes true, 2 = often true), with higher scores reflecting more problematic child's behavior. According to the T score, a behavior is considered as typical (T < 65), borderline (65–69), or significantly atypical (T > 70).

For this study, in line with our previous study (Siracusano et al., 2023), only the three main subscales have been taken into consideration: Internalizing, Externalizing Symptoms, and Total Behavior score.

2.5 Conners' parents rating scale-long form (CPRS-R:L)

The Conners' Parent Rating Scale-Revised (CPRS-R:L) (Conners et al., 1998) is a parent-report measure evaluating behavioral difficulties. The CPRS Long Form includes 80 items grouped into seven subscales (Cognitive Problems, Oppositional, Hyperactivity-Impulsivity, Anxious-Shy, Perfectionism, Social Problems, and Psychosomatic). In addition, three Conners' Global Indices (CGI) (CGI Total, CGI Restless-Impulsive, CGI Emotional Lability), an ADHD Index score, and three DSM-IV symptoms Indices (DSM-IV Total, DSM-IV Inattention, DSM-IV Hyperactive–Impulsive) are provided in order to detect children at risk for general problematic behaviors and for Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (Gurley, 2011). A T score <60 identifies a typical behavior; a score of 61–69 is part of a borderline range, whereas a >70 score becomes clinically significant.

For this study, we considered for the analyses only the score domains which were statistically significant in our previous project (Siracusano et al., 2023), that is, Cognitive Problems, Inattention score, ADHD Index, Conners_CGI Total score.

2.5.1 Parental stress assessment

Stress related to parenting was measured through self-report measure fulfilled by parents, The Parental Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF).

2.6 Parental stress measure

The stress level of parents in their role as caregivers was measured using the Parental Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF) (Abidin, 1995), a self-report questionnaire developed from the long 120 items form. The PSI-SF includes 36 items grouped into 3 domains (12 items each): parental distress (PD), dysfunctional parental–child interaction (D-PCI), and difficult child (DC).

Specifically, PD (items 1–12) provides a measure of stress related to parent characteristics, including feeling of competence, conflict with a partner, social support, restriction, and depression due to parenting. D-PCI (items 13–24) evaluates parental satisfaction with the child and their relationship with him. A high score in this domain means that the parent perceives the child as unresponsive to his expectations, and that interactions with the child do not reinforce him as a parent.

DC (items 25–36) measures the parental difficulty in taking care of the child mainly due to child's behavioral characteristics. Therefore, it is expected that parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorders report more stress in this domain. Finally, the PSI-SF provides a PSI total subscale—sum of all scores—giving a measure of the overall stress of a person as a parent.

Most of the items (33) are rated using 5-point Likert scale: from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Instead, 3 items (22, 32, 33) do not provide a Likert-type response choice.

A percentile score was measured for each subscale. Scores were corrected for age participants, according to the manual. Specifically, scores equal or above the 90th percentile amount to a clinically significant stress for all subscales, except for P-CDI where 85 is already considered a significant cut-off. On the basis of the percentiles, the whole sample included in the study (4 study groups, 1 control group) was dichotomized as clinically stressed (CS) (90 for PD, DC, and total; 85 for P-CDI) and non-clinically stressed (NCS) (<90 for PD, DC and total; <85 for P-CDI) parents.

2.7 Evaluation at T1

This assessment included an evaluation of adaptive skills and behavioral profile and parental stress through the same standardized instruments employed at T0. Only the IQ evaluation was not repeated at this timepoint.

3 STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Descriptive analysis was performed for participants' age and the time interval between evaluations. Comparisons between T0 and T1 (adaptive: ABAS-II; behavioral: Conners', CBCL; parental stress: PSI-SF) were analyzed using the paired samples t-test. Independent sample t-tests were performed to evaluate differences between sexes. Bivariate Spearman's correlations were applied to estimate the relations between differences in ABAS-II domains and cognitive and demographic variables at baseline (i.e., IQ and age). An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses. Results, if not otherwise specified, are given as means ± SDs. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.26.0 (IBM Corp.).

4 RESULTS

A sample of 32 individuals was included in the study: 18 males, 14 females (mean age 9.7 ± 4 years, median 9; range 2–18); eight carried the NSD1 5q35 microdeletion and 24 presented an intragenic mutation (see Siracusano et al., 2023 for genetic analyses details). Table 2 shows genetic characterization of individuals carrying the intragenic mutation. Mean distance between the two evaluations was 1.56 ± 0.95 years with a minimum and maximum time range, respectively, of 1 and 4 years (median 1.00).

4.1 Evaluation at baseline (T0)

At our first evaluation, participants presented a mean age of 8.1 ± 4.1 years and a mean IQ of 77.48 ± 24.9.

The evaluation of adaptive skills showed a mean score of 61.45 ± 17.23 in the ABAS-II GAC domain. Behavioral assessment performed with parental questionnaires revealed: CBCL 58.09 ± 9.7 Total Score; Conners' Parents: ADHD Index 71.04 ± 13.90; CGI: 66.17 ± 15.15.

The evaluation of parental stress showed a raw score of 79.75 ± 15.50 in the PSI Total Score. In Table 3, all the scores of the tests performed are detailed.

| T0 (M ± SD) | T1 (M ± SD) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 8.1 ± 4.1 | 9.7 ± 4.0 | - | |

| IQ | 77.48 ± 24.9 | - | - | |

| ABAS | GAC | 61.45 ± 17.23 | 62.68 ± 17.37 | 0.72 |

| CAD | 67.13 ± 19.98 | 66.90 ± 16.61 | 0.94 | |

| SAD | 68.94 ± 14.78 | 68.16 ± 13.9 | 0.80 | |

| PAD | 61.61 ± 19.58 | 62.71 ± 20.12 | 0.77 | |

| CBCL | Internalizing | 56.88 ± 11.23 | 58.58 ± 10.88 | 0.24 |

| Externalizing | 56.33 ± 8.2 | 55.42 ± 8.77 | 0.43 | |

| Total | 58.09 ± 9.7 | 58.39 ± 8.85 | 0.85 | |

| CPRS:R-L | Cognitive problems | 70.68 ± 14.34 | 69.56 ± 11.7 | 0.54 |

| DSM IV inattention | 66.96 ± 12.46 | 65.20 ± 12.29 | 0.30 | |

| ADHD index | 71.04 ± 13.90 | 70.17 ± 12.60 | 0.64 | |

| CGI | 66.17 ± 15.15 | 64.09 ± 13.09 | 0.35 | |

| PSI-SF | PD | 29.89 ± 12.28 | 27.89 ± 9.57 | 0.61 |

| D-PCI | 21.63 ± 4.65 | 22.00 ± 4.37 | 0.86 | |

| DC | 33.88 ± 7.8 | 30.00 ± 8.58 | 0.12 | |

| Total | 79.75 ± 15.50 | 76.13 ± 17.31 | 0.54 | |

- Note: The table reports main results of the comparison among evaluations (T0 and T1) including: Adaptive Behavior Assessment System second edition (ABAS-II) with conceptual (CAD) practical (PAD), social (SAD) domains and General Adaptive Composite (GAC); Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL); Conners' Parent Rating Scale-Revised (CPRS-R:L); Parental Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF) with parental distress (PD), dysfunctional parental–child interaction (D-PCI), and difficult child (DC) subindex.

Regarding the intervention attended by participants at baseline, 28/32 SoS individuals underwent an intervention, according to his/her clinical needs. 4/32 SoS individuals did not perform any kind of intervention at T0.

See Table 1 for more details about interventions at both timepoints.

4.2 Evaluation at T1

At the second evaluation, the mean age of SoS individuals was 9.7 ± 4 years.

The evaluation of adaptive skills showed a mean score of 62.68 ± SD (GAC).

The assessment of the behavioral profile was characterized by: CBCL Total Score 58.39 ± 8.85; Conners' Parents: ADHD Index 70.17 ± 12.60; CGI: 64.09 ± 13.09.

We obtained a mean raw score from the evaluation of parental stress: PSI Total Score 76.13 ± 17. 31. In Table 3, all the scores of the tests performed are detailed.

At follow-up evaluation 28/32 SoS individuals underwent an intervention, according to his/her clinical needs. 4/32 did not perform intervention at T1, of which 2/4 did not attend treatment also at baseline; the other 2/4 subjects performed intervention at baseline and suspended it at follow-up. As a whole, most of participants attended an intervention at both timepoints (even if they modified the type of therapy; see Table 1 for more details about interventions at timepoints); however, only 2 individuals did not undergo any treatment at both T1 and T0, and 4 subjects performed an intervention at only one timepoint.

4.3 Comparisons between T0 and T1 (T1-T0)

In the comparison between assessment performed at T0 and T1, no statistically significant differences were found in terms of adaptive skills and behavioral problems of SoS individuals and parental stress (Table 3).

Specifically concerning adaptive skills measured through the ABAS-II, the following results emerged: GAC: M −1.23 ± 19.39; p = 0.73; CAD M 0.23 ± 19.19, p = 0.95; SAD M 0.77 ± 16.88, p = 0.80; PAD M −1.10 ± 20.90, p = 0.77.

Even when considering sex, no statistically significant differences emerged when comparing males with females. GAC mean difference: −1.33 versus 4.77, p = 0.40; CAD mean difference: −0.56 versus 0.23, p = 0.91; SAD mean difference: −3.30 versus 2.85, p = 0.32; PAD mean difference: −0.11 versus 2.77.

We did not find any statistically significant correlation between differences in ABAS-II domains (see table) and cognitive and demographic variables at baseline: GAC and IQ (rho = 0.21; p = 0.29); GAC and age (rho = 0.11; p = 0.55).

4.4 Intervention

Given the clinical stability emerging between T0 and T1, we hypothesized that the therapy attended by participants could have influenced the results. However, being the intervention heterogeneous among individuals, we grouped participants into two: Uninterrupted Intervention Group (N = 26), included participants attending an intervention (independently from the type of treatment) during the whole period between T0 and T1; Discontinuous Intervention Group (N = 6), included individuals who did not undergo therapy or discontinued it between T0 and T1. Given the small number of individuals included in the Discontinuous Intervention Group, we performed only descriptive statistics for this section of the analysis. Observing the mean scores at T0 and T1 no differences between T0 and T1 emerged in the clinical (adaptive and behavioral) profile of Uninterrupted Intervention Group participants (Table 4).

| ABAS-II GAC | CBCL internalizing | CBCL externalizing | CBCL Total | CPRS-R:L cognitive problems | CPRS-R:L perfectionsim | CPRS-R:L hyperactivity impulsivity | CPRS-R:L emotional lability | CPRS-R:L general problems | CPRS-R:L DSM IV inattention | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | T0 | T1 | |

Uninterrupted intervention N = 26 M ± SD |

58.4 ± 15.5 | 60.1 ± 16.9 | 57.1 ± 11.4 | 59.0 ± 11.2 | 56.2 ± 8.4 | 56.6 ± 9.3 | 59.0 ± 9.8 | 58.6 ± 9.3 | 72.9 ± 13.9 | 70.9 ± 12.1 | 57.5 ± 11.4 | 52.0 ± 11.0 | 65.9 ± 14.0 | 65.8 ± 12.2 | 57.5 ± 17.3 | 55.2 ± 11.2 | 66.0 ± 15.9 | 63.2 ± 13.2 | 68.6 ± 12.4 | 66.3 ± 12.1 |

Discontinuous intervention N = 6 M ± SD |

74.2 ± 19.8 | 70.7 ± 18.3 | 59.6 ± 7.4 | 57.5 ± 0.7 | 52.6 ± 4.8 | 50.0 ± 2.8 | 54.2 ± 6.7 | 62.0 ± 5.6 | 60. 2 ± 11.8 | 59.0 ± 6.9 | 57. 2 ± 13.2 | 62. 2 ± 9.2 | 57.8 ± 12.1 | 65.2 ± 11.1 |

50.8 ± 7.6 | 49.0 ± 1.7 | 56.3 ± 11.2 | 65.3 ± 5.7 | 56.5 ± 10.8 | 58.5 ± 6.0 |

- Note: Reported in the table main scores at T0 and T1 of Sotos individuals with “Discontinuous Intervention” (who did not undergo intervention at one or even both timepoints) and with a “Uninterrupted Intervention” (who underwent an intervention at both T0 and T1, even if not the same treatment approach) among timepoints. Highlighted in bold, the scores showing a worse longitudinal profile, even if not statistically significant. Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) reported in the table refers to: the General Adaptive Composite domain (GAC) of the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System second edition (ABAS-II); Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Conners' Parent Rating Scale-Revised (CPRS-R:L) subscales.

Whereas the 6 SoS participants who did not undergo intervention at one or even both evaluations (Discontinuous Intervention Group), were characterized at T1 by a lower ABAS-II GAC score (T0 = 74.2 ± 19.8 vs. T1 = 70.7 ± 18.3), increased CBCL Total Score (T0 = 54.2 ± 6.7 vs. T1 = 62.0 ± 5.6), increased Conners' Parents Scores (Perfectionism: T0 = 57. 2 ± 13.2 vs. T1 = 62. 2 ± 9.2; General problems: T0 = 56.3 ± 11.2 vs. T1 = 65.3 ± 5.7; Hyperactivity-Impulsivity: T0 = 57.8 ± 12.1 vs. T1 = 65.2 ± 11.1; DSM-IV Inattention T0 = 56.5 ± 10.8 vs. T1 = 58.5 ± 6.0) (Table 4).

5 DISCUSSION

The present work is included in a wide clinical safeguard project of young individuals affected by genetic conditions at risk for neurodevelopmental disorders.

By means of our previous study on SoS pediatric population (Siracusano et al., 2023), we attempted to define a syndrome-specific cognitive and behavioral phenotype (whilst looking for a genotype–phenotype correlation). We then aimed to longitudinally explore the clinical evolution of most of the features previously defined.

This study provides a longitudinal characterization of the adaptive and behavioral profile of a pediatric sample of SoS individuals.

As a whole, our study reports a stability over the years of all the clinical features investigated: adaptive and behavioral. This stability was found regardless the level of cognitive skills (Intellectual Quotient < or >70) and chronological age at baseline.

We can hence affirm that the SoS participants included in this study did not manifest a worsening condition over the years despite the presence of intellectual disability.

Most of the SoS individuals enrolled in this study underwent an intervention at both timepoints even though, being type and frequency of therapies mixed, we hardly categorized individuals on the basis of the treatment approach. Despite no statistically significant improvement emerged after the baseline evaluation, the 6 SoS children with treatment defined as discontinuous during timepoints (they did not attend therapy at one or even both timepoints, according to families' choice), presented a reduction of adaptive skills and an increase of externalizing behaviors measured by the parental report Conners' Parents. Given the small sample size of the children not undergoing treatment at both evaluations, this result should be interpreted with caution; however, as a very preliminary clinical longitudinal picture, it may be useful to support the clinician in showing families the appropriate treatment pathway and follow-up frequency.

We hypothesize that the fact that no significant improvement was found at follow-up, could be explained by the time range among evaluations; a mean distance of 1.56 ± 0.95 years can be considered as a short time range for 8 years old children (mean age of our sample). As a matter of fact, cognitive and behavioral evaluations performed in preschool age lead to a better outcome which could be measured also at close-range evaluations (Chorna et al., 2020; Dimian et al., 2021; Riccioni et al., 2022).

Our findings suggest that an earlier evaluation of cognitive and behavioral skills could likewise provide an earlier targeted intervention tailored on clinical features such as behavior and adaptive functioning, both frequently put aside in a genetic condition.

In line with the adaptive and behavioral clinical stability of SoS individuals, the level of stress related to parenting did not differ between timepoints. This stability suggests the lack of improvement of parental stress reflecting the chronicity of a genetic syndrome (Siracusano, Riccioni, Fagiolo, et al., 2021; Siracusano, Riccioni, Gialloreti, et al., 2021).

Due to the small size of our sample, the longitudinal evaluation can hardly be generalized to all individuals affected by SoS. However, to the best of our knowledge, our study represents a first long-term clinical picture which may be useful to delineate syndrome specific intervention. As a matter of fact, if the clinical phenotype of a genetic syndrome is not defined at both short and long term, how can a treatment be addressed?

Main limit of this work is the sample size of the study (32/65), although it constitutes a wide sample for a rare genetic condition on which no previous behavioral longitudinal characterization has been conducted. Another limit is represented by the lack of a pre-established follow-up (T1), leading to a wide distance range among evaluations (1–4 years). Moreover, given the heterogeneity of the intervention in both terms of quantity and variety, we did not perform any statistical analysis to compare intervention groups.

6 CONCLUSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study on the behavioral profile of SoS individuals. Key-point in the definition of a clinical trajectory within a genetic condition is the detection of possible predictive factors for a better outcome. Within our SoS sample, the level of IQ and chronological age at baseline did not emerge as positive or negative predictive factors of adaptive and behavioral outcome. A stability of the clinical picture characterized all SoS individuals who underwent an intervention. Among the factors we thought responsible for this lack of improvement there are: the age of first evaluation (mean age of 8 years) in addition to the time range between evaluations (1 years and 6 months).

Our results highlight the need to early define the clinical profile of a rare genetic condition whose focus has been primarily given to medical features of the syndrome. Finally, this first longitudinal study suggests that, within SoS population, an uninterrupted intervention is a key-factor which positively contributes to the developmental trajectory.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Martina Siracusano: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology and writing—original draft, review and editing. Caterina Dante, Rachele Sarnataro, Assia Riccioni, Elisa Carloni, Cinzia Galasso: Data collection and curation. Lucrezia Arturi: Methodology, data curation, writing—review and editing. Luigi Mazzone: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing—review and editing. Mariagrazia Cicala, Leonardo Emberti Gialloreti: Formal analysis, writing—review and editing. Giuseppina Conteduca, Domenico Coviello: Genetic analyses, writing—review and editing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by the ASSIGulliver Italian Association; Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Corrente 2022 and Ricerca Corrente 2023.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest with this work.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

Informed consent was obtained from all parents/guardians of participants included in this study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

NSD1 mutations were submitted to LOVD database using accession codes ID: NSD1_303085, NSD1_289367, NSD1_269370, NSD1_303613, NSD1_00302572, NSD1_00303967, NSD1_00302847, NSD1_00303579, NSD1_00269595, NSD1_00302679, NSD1_00303973, NSD1_00303609, NSD1_00303988, NSD1_307677, NSD1_303993, NSD1_303571, NSD1_000308).