Understanding chronic pain in Neurofibromatosis Type 1 using the Neurofibromatosis Pain Module (NFPM)

Abstract

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder that can cause an individual significant chronic pain (CP). CP affects quality of life and daily functioning, yet there are limited effective treatments for CP within NF1. The current study describes the impact of CP using the Neurofibromatosis Pain Module (NFPM). The NFPM is a self-reported clinical assessment that evaluates the impact of CP across multiple domains (e.g., interference, severity, tolerance, and symptomology) and three prioritized pain regions. A cross-sectional study (N = 242) asked adults with NF1 to describe and rate their pain using the NFPM. The results indicated that they reported moderate pain severity (M = 6.6, SD = 2.0) on a 0–10 scale, that 54% (n = 131) had been in pain at least 24 days in the last 30, for 75% (n = 181) sleep was affected, and 16% reported that nothing was effective in reducing their CP for their primary pain region. The current results extend previously published work on CP within adults with NF1 and indicate that more emphasis on understanding and ameliorating CP is required. The NFPM is a sensitive clinical measure that provides qualitative and quantitative responses to inform medical providers about changes in CP.

1 INTRODUCTION

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 (NF1) is an autosomal dominant and rare genetic condition affecting one in 3000 individuals globally (Anderson & Gutmann, 2015; Gutmann et al., 2017; Legius et al., 2021). This condition can impact numerous regions of the body (e.g., brain, spine, nerves) and is often characterized by café-au-lait macules, dermal neurofibromas, skeletal abnormalities, tumors, as well as cognitive, social, and behavioral deficits that can negatively impact quality of life (Gutmann et al., 2017; Ly & Blakeley, 2019). In accordance with such symptomology, the majority of individuals with NF1 report experiencing significant chronic pain and discomfort (Allen et al., 2018; Buono et al., 2019; Fjermestad, 2019; Wolters et al., 2016). Approximately 70% of adults report using prescription medication to treat their pain (Buono et al., 2019; Créange et al., 1999). Yet there is a lack of efficacy and even a reported exacerbation of pain (Struemph et al., 2017) with prescription medication usage for this population. Despite the high prevalence of chronic pain within the NF1 population, the topic remains understudied, giving way to suboptimal treatment (Bellampalli & Khanna, 2019).

Chronic pain exposes those with NF1 to significant physical suffering as well as psychological distress (Bellampalli & Khanna, 2019; Wolters et al., 2015). Physically, individuals with NF1 report pain in the form of headaches/migraines, scoliosis/orthopedic problems (Kongkriangkai et al., 2019), and plexiform neurofibromas and other NF1-related tumors. Psychologically, research has documented increased rates of depression and anxiety among the NF1 population (Cohen et al., 2015; Doorley et al., 2021; Doser et al., 2020; Kongkriangkai et al., 2019), negative body image, less self-confidence (Granstrom et al., 2012), and reduced self-esteem (Rosnau et al., 2017). In order to provide patients with the highest quality of care, providers must understand that their patients' pain extends beyond physical symptoms.

Healthcare providers commonly use numerical scales to obtain a self-reported rating of their patients' current level of pain (Collins et al., 2022; Karcioglu et al., 2018). Experience of pain is unique, multifaceted, and subjective (Cohen et al., 2021; Gatchel et al., 2007), and while numerical scales may offer healthcare providers information about patients' perceived severity of their pain, in order to obtain a comprehensive understanding of experience with pain there is a clear need for additional qualitative and contextual information. However, the etiology, subsequent symptomology, and impact on functioning of chronic pain remains understudied, measured, and considered in routine treatment of NF1. In an effort to address this gap, the current cross-sectional survey study sought to understand more fully the impact of chronic pain on adults with NF1 by using the novel Neurofibromatosis Pain Module (NFPM).

2 METHODS

2.1 Editorial policies and considerations

The current descriptive study was approved by the first author's Institutional Review Board (2000030489) and abides by the Declaration of Helsinki (1978). All participants were requested to read the consent form and provide an electronic signature if they agreed to participate in the study.

2.2 Participants

Potential participants were recruited through the Children's Tumor Foundation (CTF) patient registry via email solicitation between February 2023 and April 2023. All participants were unique and had not participated in previous research conducted within our laboratory. Inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) adults 18 years and older; (2) registered within CTF (confirmed diagnosis of NF1 by a medical provider is required for the registry); and (3) pain interference aggregate score of three or more in the last 2 weeks using the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) scale (Cleeland & Ryan, 1994). Participants were excluded if they: (1) had documented severe co-occurring psychiatric disease (e.g., bipolar, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder) as measured by the SCID assessment; (2) had moderate to severe depression (>15) as assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) or moderately severe anxiety (>15) assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., 2006); or (3) if the participant had participated in a previous research project from the first author's lab.

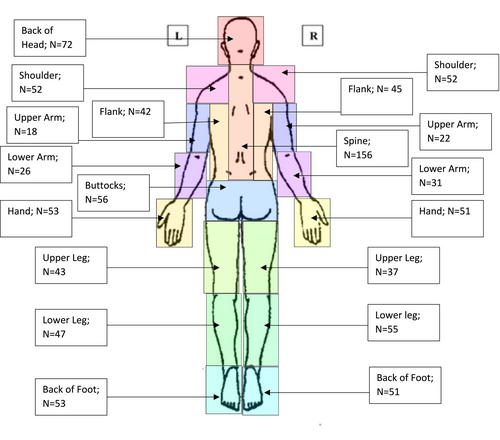

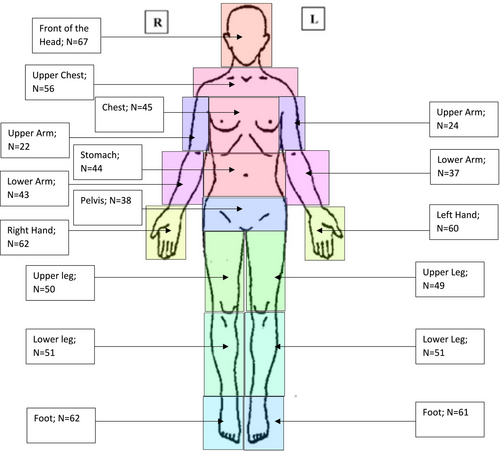

2.3 Neurofibromatosis Pain Module

The NFPM (Buono in preparation) is a 39 question patient-reported clinical assessment that evaluates chronic pain from four different domains (i.e., interference, severity, tolerance, and symptomology). The NFPM was developed through a mixed-methods approach that included input from both NF1 patients and providers. It asks the person to self-select up to three of their most prevalent pain regions (primary, secondary, and tertiary) that are affecting their body. Additionally, participants are asked to describe their pain across all three regions from a list of descriptors (e.g., burning, stabbing, tingling). For each region, the individual completes 13 total questions (5 multiple choice, 2 short answer, and 6 Likert-based rating) concerning the perceived severity, interference, tolerance, antecedent of pain (if applicable), impact of their pain. The measure also includes two anatomically neutral silhouettes where the respondent can identify the pain location and where the pain radiates (see Figures 1 and 2). Within the NFPM, there are two open-ended questions (see Table 5) to understand more about the causes of pain and factors that exacerbate pain. Participants were allowed to answer in a multi-line textbox. Evaluating each pain region takes approximately 5 min, with the total assessment taking, on average, 15 min. Preliminary evidence indicates the NFPM displays good psychometric properties (Cronbach's alpha = 0.82).

2.4 Procedures

A mass email was sent to CTF registry patients providing the initial description and goals of the study. The email also included an embedded link to pre-screen potential participants based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and completion of the PHQ-9, GAD-7, SCID, and BPI-SF assessments. Participants who met inclusion criteria were contacted by the research team and provided with the link for the NFPM. The NFPM was hosted and maintained by Qualtrics (www.Qualtrics.com). Participants had the option to refuse to answer any given item and were not obligated to complete the entire survey in one sitting. Participants had up to 2 weeks to complete the NFPM after consenting. Following completion of the survey, participants were entered in a lottery to win one of four 50-dollar Amazon gift cards.

2.5 Data Analysis

Using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 28 (IBM Corp, Chicago, IL), descriptive statistics were calculated for the demographics of the study sample and response frequencies for each NFPM item. Although a formal qualitative analysis was not performed, two members of the research team (FB and KL) collapsed the open-ended items into categories according to what caused or worsened different types of pains. The frequencies of these responses were then calculated.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

The email request went out to 723 adults with NF1 within the United States; 290 (40%) individuals with NF1 responded and were initially recruited for the study. Of those who were initially recruited, 48 individuals did not complete the study, 34 who consented did not start the survey, 10 declined to participate, and 4 individuals did not meet inclusion criteria. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the study sample. For the 242 subjects who completed the NFPM, the mean age was 48.3 years (SD = 11.7 years); 173 (73%) identified as female, and the sample was predominantly White (n = 184, 76%). Participants described their NF1 symptoms as either mild (n = 38; 16%), moderate (n = 145; 60%), or severe (n = 58; 24%). Of note, 122 (50%) of participants indicated they had a medical provider who specializes in NF1, but only 31% of the doctors (n = 75; 31%) are associated with a registered NF Clinic (https://www.ctf.org/research/nf-clinic-network).

| Sample size | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Current age, M (SD) | 48.3 (11.7) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 184 | 76% |

| Hispanic | 17 | 7% |

| Black | 23 | 10% |

| Asian | 6 | 3% |

| Multiple races | 4 | 1% |

| Other | 8 | 3% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 64 | 26% |

| Female | 176 | 73% |

| Transgender | 2 | 1% |

| NF Description | ||

| Mild | 38 | 16% |

| Moderate | 145 | 60% |

| Severe | 58 | 24% |

| Age of diagnosis, M (SD) | 11.4 (12.4) | |

| Family incidence of NF | ||

| Yes | 127 | 53% |

| No | 93 | 38% |

| Missing | 22 | 9% |

| Medical provider specializes in NF | ||

| Yes | 109 | 45% |

| No | 122 | 50% |

| Not sure | 11 | 5% |

| Medical provider associated with a NF clinic | ||

| Yes | 75 | 31% |

| No | 133 | 55% |

| Not sure | 31 | 13% |

3.2 Descriptives of NFPM

Total responses differed per the primary, second and tertiary pain regions, with the primary region having 242 responses, secondary region having 115 responses and tertiary region having 26 responses. However, there were even distributions of chronic pain affecting these regions. As seen on Table 2, the highest self-reported events impacted by pain were sleep (n = 181; 75%), ability to exercise (n = 164; 68%), mood regulation (n = 163; 67%), and ability to pay attention (n = 144; 60%). For their primary pain, it was noted that (n = 120; 50%) of the individuals reported their pain was worse since their last visit with their doctor. Respectively, 22 (9%) for primary pain, 14 (12%) for secondary pain, and 4 (15%) for tertiary pain reported single pain descriptors. The remainder of the sample selected two or more pain descriptors.

| Primary pain (n = 242) | Secondary pain (n = 115) | Tertiary pain (n = 26) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Maybe | Yes | No | Maybe | Yes | No | Maybe | |

| Sleep | 181 | 43 | 13 | 88 | 21 | 6 | 23 | 2 | 1 |

| Ability to work | 134 | 60 | 35 | 67 | 38 | 10 | 17 | 6 | 3 |

| Mood | 163 | 37 | 24 | 85 | 23 | 7 | 20 | 5 | 1 |

| Physical/Sexual relationships | 124 | 71 | 27 | 60 | 44 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 1 |

| School | 46 | 143 | 14 | 28 | 81 | 6 | 6 | 17 | 3 |

| Diet | 72 | 121 | 24 | 36 | 68 | 11 | 8 | 16 | 2 |

| Self-care | 102 | 89 | 34 | 59 | 45 | 11 | 17 | 9 | 0 |

| Managing time | 98 | 96 | 32 | 60 | 47 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 1 |

| Talking with others | 75 | 122 | 29 | 42 | 59 | 14 | 7 | 17 | 2 |

| Ability to pay attention | 144 | 54 | 31 | 60 | 37 | 18 | 18 | 7 | 1 |

| Exercise | 164 | 47 | 22 | 76 | 26 | 13 | 21 | 3 | 2 |

| Has your pain gotten worse since your last visit? | 120 | 75 | 47 | 56 | 43 | 21 | 10 | 14 | 2 |

For primary, secondary, and tertiary pain regions, the mean reported pain intensity over the last week was in the moderate level (primary 6.6, secondary 6.3, and tertiary 6.4) on a 0 to 10 scale where 0 was no pain and 10 was the worst pain imaginable. Pain scores fluctuated over the course of the last month, as seen on Table 3. It was noted that 153 (63%) of primary pain was experienced at minimum 6 out of the 7 days, and 131 (54%) reported that this pain occurred between 24 and 30 days in the last month. When asked to describe their pain using a keyword, 116 (48%) stated “constant,” and a total of 84% of individuals either reported “constant” or “frequent.” When asked what strategies can help relieve the pain, 39 (16%) individuals reported “nothing,” 47 (19%) had attempted two strategies, and 110 (45%) had attempted three or more strategies to reduce their primary pain (Table 4). Participants were asked to select where their primary, secondary, and tertiary pains were located using gender-neutral silhouettes (Figures 1 and 2). As noted for the primary pain, all regions of the body had been selected, with the least frequent being the back of the upper arm (n = 22) and the most frequent being the spine (n = 156).

| Primary pain (n = 242) | Secondary pain (n = 115) | Tertiary pain (n = 26) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity over last week (M/SD) | 6.6 (2.05) | 6.32 (2.0) | 6.4 (2.1) |

| Pain intensity over last month (M/SD) | 6.9 (2) | 5.66 (1.8) | 6.8 (2.2) |

| In past week, how many days have you experienced the pain | |||

| 1 | 9 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 0 |

| 2 | 11 (5%) | 8 (7%) | 1 (4%) |

| 3 | 12 (5%) | 9 (8%) | 4 (16%) |

| 4 | 15 (6%) | 11 (10%) | 1 (4%) |

| 5 | 23 (10%) | 11 (10%) | 2 (8%) |

| 6 | 26 (11%) | 6 (5%) | 3 (12%) |

| 7 | 127 (52%) | 64 (56%) | 14 (54%) |

| In last month, how many days have your experienced pain | |||

| 0 to 7 | 32 (13%) | 13 (11%) | 3 (12%) |

| 8 to 15 | 29 (12%) | 16 (14%) | 4 (16%) |

| 16 to 23 | 50 (21%) | 23 (20%) | 3 (12%) |

| 24 to 30 | 131 (54%) | 63 (55%) | 16 (62%) |

| What word describes your pain | |||

| Constant | 116 (48%) | 53 (46%) | 8 (31%) |

| Frequent | 86 (36%) | 44 (38%) | 11 (42%) |

| Occasional | 29 (12%) | 14 (12%) | 4 (16%) |

| Rarely | 4 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 0 |

| Other | 6 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (12%) |

| Strategies to relieve pain | Primary (n = 242) | Secondary pain (n = 115) | Tertiary pain (n = 26) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nothing | 39 (16%) | 22 (19%) | 6 (23%) |

| Prescription medications | 16 (7%) | 7 (6%) | 0 |

| OTC | 12 (5%) | 7 (6%) | 0 |

| Sleep or rest | 4 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 |

| Talking to someone | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ignoring | 3 (<1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Movement | 2 (<1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Ice/Heat | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Yoga or stretching | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Other | 7 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (8%) |

| 2 or more | 47 (19%) | 22 (19%) | 6 (23%) |

| 3 or more | 110 (45%) | 49 (43%) | 12 (46%) |

3.3 Open-ended responses

In understanding the sources of the pain experience for their primary pain, the top categories for causes of pain were: “movement” (n = 56; 23%), “participants identified no known cause of pain” (n = 50; 20%), and “aggravation of the tumor” (n = 48; 20%). When asked what worsens the pain, participants noted: “daily activities” (n = 60; 25%), “movement” (n = 56; 23%), and “aggravation of the tumor” (n = 46; 19%). The remainder and descriptions of the generalized categories are noted in Table 5.

| Causes (N = 242) | Worsens (N = 239) | |

|---|---|---|

| Movement (e.g., walking, lifting, bending, prolonged activity) | 56 (23%) | 56 (23%) |

| Participants identified no known cause of pain | 50 (20%) | 25 (10%) |

| Aggravation of fibroma location (e.g., rubbing, hitting, bumping, pinching) | 48 (20%) | 46 (19%) |

| Daily activities as causal source (e.g., household chores, driving, sitting, standing) | 44 (18%) | 60 (25%) |

| Temperature changes (e.g., weather, showering) | 19 (8%) | 23 (10%) |

| Emotional/Physical status (e.g., stress, fatigue, menstrual cycle) | 12 (5%) | 17 (7%) |

| Sensory causes (e.g., light, darkness, clothing, noise) | 8 (3%) | 7 (3%) |

| Acute/Chronic medical status (e.g., surgery, tumors, scoliosis) | 5 (2%) | - |

| Otherwise not specified | 5 (2%) |

4 DISCUSSION

The current study aimed to extend the knowledge base in the current literature by providing further clarification on the impact of chronic pain in adults with NF1. By evaluating the participants' chronic pain across three different pain regions (primary, secondary, and tertiary) and letting participants self-assign their regions of predominant pain, we were able to gather a wealth of information regarding their experience of pain. Results indicated that all participants had at least one area of moderate chronic pain, and a majority of the participants had a second area of moderate level pain. Whereas previous chronic pain measures only ask about one pain area when, in fact, people with NF1 have commonly multiple pain areas. The current findings suggest that assessing only one pain region may not yield an adequate understanding of the nature and extent of chronic pain in the NF1 population, something that has not been heretofore reported.

The prevalence of CP among individuals with NF1 is evidenced by the self-description of “constant” and or “frequent” related to participants' primary pain which constituted 83% of total responses. Aggregate pain severity scores for the three regions above were 6.0 on a 1–10 scale, indicating moderate to moderate/high pain severity. Moreover, CP was not limited to a single region of the body. In fact, as noted in Figures 1 and 2, each region was selected. Chronic pain affected individuals' quality of life and their ability to sleep, exercise, regulate their mood, and pay attention to tasks. The findings from this study also support previous research stating that the available treatment options are relatively ineffective (Burns et al., 2011; Struemph et al., 2017). The current study indicates that individuals with NF1 often struggle to reduce their pain symptoms by reportedly attempting 2 or 3 more strategies to relieve pain (e.g., heat, sleeping, or physical activity). These findings support previous research concerning the ineffectiveness of current strategies to mitigate or reduce chronic pain (Buono et al., 2019). Thus, requiring multiple strategies (e.g., more than two strategies) to lower pain symptoms.

The open-ended questions in which participants noted what they felt triggered or worsened their pain provided context on the impact of chronic pain for individuals with NF1. In both cases (causing or worsening pain), movement activities or the sensitive nature of the tumor when physically bumped or rubbed initiated symptoms. Interestingly, what caused the pain to occur was unknown for 20% of the respondents, potentially indicating that their pain could be triggered by a combination of different stimuli. This lack of understanding about the underlying cause of the pain may increase the potential for generalized anxiety, hopelessness, and reduced quality of life. These findings emphasize the complexity of chronic pain within NF1 patients.

As noted, 92% of participants indicated two or more descriptors related to their primary pain region, potentially indicating that participants may not understand the difference between the sensorial pain descriptors or that their pain is multi-sensorial (e.g., burning, throbbing, and tingling). Given that pain is a subjective experience, differences among seemingly identical pain conditions can occur, thus leading to a variety of descriptors being affixed to those identical pain conditions (Boureau et al., 1990). Previous research has indicated that pain descriptors should be classified by pain disorders (Fernandez et al., 2011); however, research in adults with NF1 has yet to derive classifications for this specific disease. Moreover, research with NF1 adults has yet to establish how pain types (e.g., burning, throbbing, stabbing) can be discriminated. In addition, given the multitude of NF1-related symptoms that cause pain and discomfort (e.g., plexiform and cutaneous tumors, scoliosis, and bone abnormalities), the heterogeneity of pain descriptors is not unexpected.

Only 45% participants had a medical expert that specialized in NF. The rarity of the disease, in combination with the lack of medical experts trained in NF1 and the complexity of chronic pain, creates a need for multidisciplinary care for these patients. Findings from this study highlight the need for a thorough evaluation of chronic pain in individuals with NF1 that goes beyond Likert-based responses. Scales such as the visual analogue scale are predominantly severity-based (e.g., no pain to worst pain imaginable) and limited to a specific range of time; therefore, they neither provide a sufficiently thorough understanding to the medical provider about pain over time nor validate the experience of the individual suffering from the pain. Thus, given the limited knowledge that can be gained through existing measures used by NF1 providers, it is critical that evaluations encompass a more complete understanding of the patient to ensure that the patient can be provided the best care.

The current study is not without limitations. As noted in Figures 1 and 2, pain among this patient population was not limited to a single anatomic region and instead they identified multiple regions. In other words, we could not distinguish where their primary, secondary, and tertiary pain originated. Furthermore, the presentations of Figures 1 and 2 indicate that chronic pain in NF1 is diffuse and not necessarily constrained to the exact location of the tumor. A second limitation of the current study is the relatively small sample size and the lack of a random sampling strategy; the findings may therefore be of limited generalizability. Yet, given the rarity of the condition, the presentation provides an initial understanding. A third limitation is the current study is a cross-sectional design and completing only one time-point limits on the understanding of the duration of the chronic pain. A final limitation of the study is that participants having severe psychiatric symptoms and/or other co-occurring diagnoses that could artificially inflate chronic pain scores. Given the parameters of the study, we attempted to exclude severe psychiatric patients and in so doing, the current study may also limit the generalizability of the findings. However, in the instructions of the NFPM, we only asked the participant to describe their NF-related pain.

5 CONCLUSION

Chronic pain has substantial effects on individuals living with NF1. The current study demonstrates that chronic pain can affect individuals with NF1 across all areas of life and multiple regions of their body. Clinical tools such as the NFPM will be useful in providing a more comprehensive description of NF1-related pain to inform treatment plans of providers to facilitate patient care.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

FDB: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; formal analysis; original draft writing, reviewing, and editing. KL: Data curation; methodology; original draft writing, reviewing, and editing. WTZ: Conceptualization; supervision; reviewing, and editing. LEG: Supervision; reviewing, and editing. SM: Conceptualization; supervision; reviewing, and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Funding from this project came from Children's Tumor Foundation, Clinical Research Award (#2021-10-001, PI: Buono, Frank).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.