ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy due to novel mutations in ACBD5 and with additional features including ovarian insufficiency

Abstract

Acyl-CoA-binding domain-containing protein 5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy (ACBD5) is a peroxisomal disorder due to deficiency of ACBD5. Presenting features include retinal dystrophy, progressive leukodystrophy, and ataxia. Only seven cases of ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy have been reported in the literature to date, including one other case diagnosed in adulthood. Here we report a case with novel compound heterozygous ACBD5 mutations, presenting with the common features of rod monochromatism and progressive leukodystrophy with spasticity and ataxia. Additional novel clinical features included head and neck tremor and ovarian insufficiency. The patient's symptoms were present since infancy, but a diagnosis was only reached in adulthood when whole exome sequencing was performed. This case, which reports two novel mutations and additional clinical manifestations, contributes to the emerging phenotype of ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy, and delineation of the natural history and disease progression.

1 INTRODUCTION

Acyl-CoA-binding domain-containing protein 5 (ACBD5) is a peroxisomal membrane protein. Although its specific function is incompletely understood, it is known to bind to long-chain acyl-CoA (LC-CoA) and very-long-chain acyl-CoA (VLC-CoA) esters, with preferential binding to VLC-CoAs (Yagita et al., 2017). It is considered to be involved in the import of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) into peroxisomes (Yagita et al., 2017). Deficiency of ACBD5 results in accumulation of VLCFA-containing phospholipids (Wanders, 2018; Yagita et al., 2017). In addition, through interactions with vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP)-associated protein B, ACBD5 tethers peroxisomes to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Costello et al., 2023). Deficiency of ACBD5 results in reduced peroxisome-ER contact, with a resultant increase in peroxisomal movement and reduced capabilities for peroxisomal membrane growth (Costello et al., 2023). Mutations in ACBD5 result in the peroxisomal disorder ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy (ACBD5, OMIM 616618) (Ferdinandusse et al., 2017). Seven cases of ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy have been reported to date, including one case diagnosed as an adult (Abu-Safieh et al., 2013; Bartlett et al., 2021; Ferdinandusse et al., 2017; Gorukmez et al., 2022). Here we report a case, diagnosed at age 27, with novel compound heterozygous ACBD5 mutations and previously unreported clinical features.

2 CASE REPORT

The proband is a 30-year-old female, born to non-consanguineous parents. Her father is of Scottish heritage and her mother of Irish heritage, and she has one healthy brother. She was born at term by forceps-assisted delivery for frank breech position and no neonatal concerns were identified. She met early motor milestones, sitting at 7 months, crawling at 9 months, and then walking at 15 months of age with a wide based gait. She was speaking in sentences by 3 years. There were no dysmorphic features.

Multidirectional nystagmus was noted from 2 months of age. She subsequently developed photophobia and very poor vision, leading to the diagnosis of rod monochromatism at 18 months of age. An electroretinogram (ERG) at age one, demonstrated a decreased dark-adapted response and an extremely decreased light-adapted response, suggestive of rod-cone dystrophy. Repeat ERG at age 15 demonstrated absent rod, mixed, and cone responses. Additional ocular features included a right esotropia, and minor restriction in abduction and up-gaze.

From 2 years of age, she demonstrated progressive ataxia, lower limb spasticity, and weakness, with superimposed episodes of reversible deterioration with fevers. She required a walker by 4 years of age, and a wheelchair at 6 years. By age 12, she had no functional use of her lower limbs and developed joint contractures of the knees and ankles. Spasticity and weakness in the upper limbs progressed more slowly but was associated with prominent superimposed ataxia. Additional neurologic examination features included impaired 2-point discrimination and proprioception in the feet, with a normal upper limb sensory examination, and a dystonic head tremor.

A progressive dysarthria developed from age three and was followed by dysphagia from age 10. She developed urinary incontinence by age 12, which later progressed to urinary retention, requiring a suprapubic catheter insertion at 25 years. Her cognition has gradually declined over time, and from adolescence she has developed prominent emotional lability and anxiety.

Other medical issues include primary ovarian insufficiency, an incidental ovarian cyst detected during investigation for abdominal pain at 18 years of age, osteoporosis (attributed to immobility and ovarian insufficiency) and renal calculi. Age of menarche was 12–13 years, but periods were light and irregular, and have now ceased. She has been managed with estrogen topical patches.

3 INVESTIGATIONS

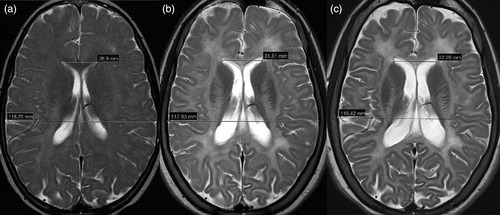

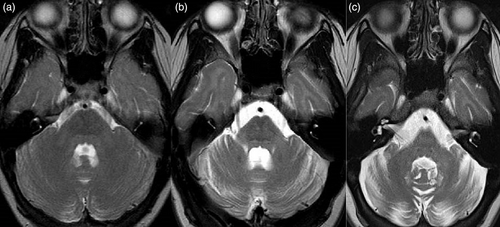

Laboratory evaluation revealed normal full blood count, renal function, and liver function. Hormonal testing at age 23 demonstrated a low estradiol level (29.7 pmol/L) with elevated LH (85.3 IU/L) and FSH (197.4 IU/L) levels; a profile consistent with ovarian insufficiency or post-menopausal state. Plasma VLCFAs, tested at age 15, were normal: hexacosanoate 0.83μmol/L [0.33–1.13], C26:C22 ratio 0.020 [0.007–0.024], C24:22 ratio 0.97 [0.60–1.02]. Serial MRI scans of the brain demonstrated progressively increasing diffuse high T2 signal intensity, consistent with leukodystrophy, throughout all cerebral white matter, including the tracts of the basal ganglia, resulting in an increased discrimination of gray to white matter structures on T2 imaging (Figure 1). Imaging revealed continuing progression of cerebral (Figure 1), infratentorial (Figure 2), and spinal cord atrophy on serial imaging, in keeping with secondary axonal loss. Progressive ex-vacuo dilation of the lateral (Figure 1) and third ventricles was demonstrated; third ventricular transverse distance (width) was 6.7 mm at age 18 and 8.5 mm at age 27, coronal T2 MRI was not performed aged 10. Comparable 3D imaging for volumetrics was not available. Another finding was the presence of abnormally small bony orbits with paucity of retrobulbar fat. Spinal MRI completed at 12 and 18 years of age demonstrated progressive atrophy of the cord, especially in the thoracic region, with relative sparing of the cervical and distal (lumbar) expansions. This was most marked at T4-7 levels, with associated subtle abnormal intramedullary T2 signal.

Brainstem auditory evoked potentials, at age 18, were attenuated and delayed, consistent with symmetrical central nervous system demyelination of the auditory pathways. Nerve conduction studies at age 18 were normal aside from giant F-wave amplitudes with normal F-wave latency. Median nerve somatosensory evoked potentials were not reliably identified at age 18. Bilateral femoral head dysplasia and coxa valga were identified on X-rays at age 18.

Chromosomal microarray demonstrated a normal female profile. Trio exome sequencing was undertaken at SEALS Genetics with reads aligned to Human Reference Sequence GRC38 and single nucleotide and short insertion/deletion variants identified using the Dragen Server in Illumina Basespace. Variant filtering, prioritization, and reporting were performed using the Genomics Annotation and Interpretation Application (GAIA) in-house pipeline. This identified compound heterozygous truncating variants in ACBD5. The first mutation, c.979G > T, p.Gly327*, is a nonsense variant, resulting in a premature stop codon at amino acid position 327. The variant is not present in the normal population database gnomAD, nor the ClinVar database. It is classified as pathogenic by ACMG criteria (PVS1, PM2, PM3) (Karczewski et al., 2020; Landrum et al., 2018; Richards et al., 2015). The second variant, c.399del, p.Ile134Leufs*6, results in a one base pair deletion, causing a frameshift starting at codon Ile134. The new reading frame ends in a stop codon at position 6. This variant is not present in gnomAD, or ClinVar databases (Karczewski et al., 2020; Landrum et al., 2018). This variant is classified as pathogenic by ACMG criteria (PVS1, PM2, PM3) (Richards et al., 2015).

4 DISCUSSION

Our case advances the understanding of the natural history and clinical features in ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy. This condition was first identified in three affected siblings presenting with cone-rod dystrophy, spastic paraparesis, psychomotor delay, and leukodystrophy (Abu-Safieh et al., 2013). Rod-cone dystrophy, delayed or regression of motor development, progressive cognitive decline, and imaging features of a progressive leukodystrophy are common features (Abu-Safieh et al., 2013; Bartlett et al., 2021; Ferdinandusse et al., 2017; Gorukmez et al., 2022). Other features of ataxia, dysarthria, cleft palate, facial dysmorphisms, progressive microcephaly, and seizures are reported sporadically (Abu-Safieh et al., 2013; Bartlett et al., 2021; Ferdinandusse et al., 2017; Gorukmez et al., 2022). Although prior cases of ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy have demonstrated an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, a recent report of a father–daughter pair has posited that heterozygous variants in ACBD5 may predispose to a more restricted clinical syndrome with isolated retinal features. Both reported individuals were found to have a heterozygous variant of uncertain significance in ACBD5 with clinical features of rod-cone dystrophy and foveal atrophy, respectively (Pappaterra-Rodriguez et al., 2022).

In this condition, the earliest manifestations are generally nystagmus and retinal dystrophy, presenting within the first months of life. Early motor development was normal in our case, but can be variable, with both normal and delayed milestones reported in other cases (Abu-Safieh et al., 2013; Bartlett et al., 2021; Ferdinandusse et al., 2017; Gorukmez et al., 2022). The natural progression has generally been of progressive spastic paraparesis (onset ranging from 2 to 9 years) and ataxia, more severely affecting the lower limbs. The progressive motor deterioration necessitates wheelchair use in the teenage years. Based on the findings of our case and the other reported adult case, progressive dysarthria, urinary dysfunction, and cognitive decline appear to develop as patients enter adulthood. Plasma VLCFAs are typically abnormal in ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy but were normal in our case.

We hypothesize that the variability of early motor development relates to the extent that alternate mechanisms can sustain peroxisomal beta-oxidation, given the presumptive complete loss of function of ACBD5. The superimposed episodes of reversible deterioration in this patient during fever are likely a consequence of further decompensation, in the setting of heightened stress placed on an already compromised cellular system. Episodes of reversible deterioration may alternatively occur because of impaired peroxisome-ER interactions. Peroxisomes proliferate or decrease in number in response to environmental stimuli, while impaired membrane growth related to ACBD5-deficiency may affect this dynamic process and reduce the responsiveness of the peroxisomal system to physiologic stressors (Darwisch et al., 2020; Schrader et al., 2006). Notably, two other cases of ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy developed seizures at times of fevers and febrile episodes have been reported to exacerbate neurologic symptoms in the setting of an alternative peroxisomal disorder (Gorukmez et al., 2022; Hashimoto et al., 2005).

Diffuse white matter hypomyelination, leukodystrophy, and generalized atrophy are commonly reported imaging findings in ACBD5-related retinal dystrophy. Serial MR imaging in this case demonstrated progressive white matter T2 hyperintensity and generalized atrophy on interval brain imaging. We interpret the relatively less marked abnormalities on childhood scans and progressive white matter changes as leukodystrophic rather than a primary hypomyelination. In this case, MRI demonstrated progressive cord atrophy, although this is harder to display as a single image and is therefore not presented in the figures. This finding was supported on electrophysiological testing by loss of tibial SSEPs despite preserved peripheral nerve conduction studies.

Our case demonstrated the previously unreported features of a dystonic head and neck tremor and primary ovarian failure. Though a dystonic tremor has not been previously reported, given this feature only developed in adulthood in our patient, this may represent a late manifestation of the disease.

Premature ovarian insufficiency has been previously described in association with other peroxisomal disorders, although is not a common feature (Karlberg et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022). Ovarian peroxisomal function remains incompletely understood, but peroxisomes are thought to be involved in gonadotropic steroid and cholesterol synthesis (Wang et al., 2022). Peroxisomes are suspected to play a role in the maintenance of ovarian redox balance, preventing reactive oxygen species-related meiotic arrest and permitting successful progression through folliculogenesis (Wang et al., 2022). Further hypothesized roles include maintenance of fatty acid species homeostasis, and provision of ATP and nutrition through beta-oxidation (Wang et al., 2022). Our patient presented with premature ovarian insufficiency, which we suspect related to the peroxisomal disorder, with no alternative cause identified. This feature was not reported in the one other published adult case, who was female (Bartlett et al., 2021).

5 CONCLUSION

We describe a case of ABCD5-related retinal dystrophy with leukodystrophy, a rare peroxisomal disorder. Our case, in conjunction with those previously described, contributes to the knowledge of the emerging phenotype and natural history of this rare disorder.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Laura Ivete Rudaks was the primary author of the manuscript and performed collation of the clinical data. James Triplett, Katrina Morris, and Stephen Reddel contributed to the writing of the manuscript and edits. Lisa Worgan was the senior author, contributing to the conception, collation of clinical data, writing of the manuscript, and final approval.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the patient and family for permission to share this case. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley - The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.