Undifferentiated psychosis or schizophrenia associated with vermis-predominant cerebellar hypoplasia

Abstract

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a well-studied neuropsychiatric condition that has been shown to have a high degree of genetic heritability. Still, little data on the specific genetic risk variants associated with the disease exists. Classification of the SCZ phenotype into SCZ-related endophenotypes is a promising methodology to parse out and elucidate the specific genetic risk variants for each. Here, we present a series of 17 previously reported individuals and a new proband with similar SCZ-related neuropsychiatric characteristics and shared brain imaging findings. Unsurprisingly, these individuals shared classic psychiatric features of SCZ. Interestingly, we also identified shared neuropsychiatric features in this series of individuals that had not been highlighted previously. A consistently decreased IQ, memory impairment, sleep and speech disturbances, and attention deficits were commonly reported findings. The brain imaging findings among these individuals also consistently showed posterior vermis predominant cerebellar hypoplasia (CBLH-V). Most individuals' diagnoses were initially described as Dandy–Walker malformation; however, our independent review of imaging suggests a more consistent pattern of posterior vermis predominant cerebellar hypoplasia rather than true Dandy–Walker malformation. While the specific genetic risk variants for this endophenotype are yet to be described, the aim of this paper is to present the shared neuropsychiatric features and consistent, symmetrical brain image findings which suggest that this subset of individuals comprises an endophenotype of SCZ with a high genetic solve rate.

1 INTRODUCTION

More than 20 prior reports describe an association between recurrent undifferentiated psychosis or schizophrenia (SCZ) and cerebellar malformations on brain imaging, variably described as Dandy–Walker malformation (malformation or syndrome or variant). Here, we report another individual with undifferentiated psychosis and vermis-predominant cerebellar hypoplasia (CBLH-V), and review the neurodevelopmental, psychiatric and brain imaging phenotypes in 18 individuals, including our proband, finding a more homogenous brain imaging phenotype than prior reports suggest. Notably, none of the subjects reported had Dandy–Walker malformation, but rather symmetric CBLH-V with variable enlargement of the posterior fossa. Our analysis suggests that psychosis or SCZ-associated CBLH-V comprises an endophenotype that is likely to have a genetic basis.

This is an important concept as identification of genetic risk variants for psychosis and SCZ remains challenging given the broad range of symptom severity and neuropsychiatric deficits. The use of SCZ-related endophenotypes has been suggested as an approach to provide greater specificity that may contribute to the identification of genetic risk variants. The concept of an endophenotype in SCZ was first introduced by Gottesman and Shields as a means to study the link between genetic risk variants and lower-level biological processes in conditions with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes such as SCZ or undifferentiated psychosis (Gottesman & Shields, 1972; Greenwood et al., 2019).

2 METHODS

This study obtained ethics approval from the University of Minnesota IRB and informed consent was obtained. We evaluated a teen boy with multiple mild neurodevelopmental deficits from early childhood and onset of hallucinations and other features of SCZ at 10 years who had moderate CBLH-V on brain imaging. This prompted us to review prior reports of psychosis or SCZ in association with cerebellar malformations.

We performed a literature review using pairs of search terms with the first search term either “psychosis” or “schizophrenia,” and the second search term “cerebellar hypoplasia,” “Dandy–Walker malformation” or “Dandy–Walker variant.” Our search yielded 17 papers from 2007 to 2021 describing 20 individuals. Three papers were discarded due to inadequate or no brain imaging, leaving 17 reported individuals plus our proband (Bozkurt Zincir et al., 2014; Buonaguro et al., 2014; Dawra et al., 2017; Ferentinos et al., 2007; Gama, 2019; Gan et al., 2012; Kvitvik Aune & Bugge, 2014; Langarica & Peralta, 2005; Papazisis et al., 2007; Porras Segovia et al., 2021; Rohanachandra et al., 2016; Ryan et al., 2012; Trehout et al., 2019; Turner et al., 2001; Williams et al., 2016).

No genetic testing was performed in any of the reported individuals. To assess phenotypic patterns suggesting a common underlying etiology in these individuals, Tables 1a and 1b compare the demographic information, phenotypic presentations, and brain imaging results of our 17 analyzed subjects. The psychiatric descriptors were the most robust, but the neurologic findings were of particular importance for our analysis to determine genetic versus non-genetic etiology. Since many of these descriptions were incomplete, we paid particular attention to the most commonly reported neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental phenotypes. These included IQ (or intellectual disability, learning disabilities), attention deficits, autistic features, seizures, sleep disturbances, and aggression.

| Patient | REF | Hypoplasia | Enlarged | Our DXa | Pub DXb | Agec | Sex | FIQ | PIQ | VIQ | FIG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vermis | HEM | 4V | PF | ||||||||||

| 1 | + | +d | + | CBLH-V | 11 | M | 69 | 62e | 96 | ||||

| 2 | 3 | + | − | CBLH-V | Variant | 30 | F | 75 | 75 | 75e | + | ||

| 3 | 4 | + | CBLH-V | DWM (S) | 29 | F | 75e | 75e | 75e | ||||

| 4 | 5 | + | − | CBLH-V | DWM (S) | 18 | M | 62e | 62e | 62e | |||

| 5 | 6 | + | − | CBLH-V | MCM | 21 | F | 80 | 70 | 89 | + | ||

| 6 | 7 | + | − | Borderline | CBLH-V | Variant | 34 | F | 62e | 62e | 62e | + | |

| 7 | 8 | + | − | Borderline | CBLH-V | DWM (C) | 15 | F | 75e | 75e | 75e | + | |

| 8 | 8 | + | − | Borderline | CBLH-V | DWM (C) | 13 | M | 127 | 125 | 123 | + | |

| 9 | 8 | + | − | + | CBLH-V-MCM | DWM (C) | 32 | M | 62e | 62e | 62e | + | |

| 10 | 8 | + | − | − | + | CBLH-V-MCM | DWM (C) | 20 | M | 69 | 69 | 74 | + |

| 11 | 9 | + | + | CBLH-V | Variant | 22 | M | 79 | 79 | 79 | + | ||

| 12 | 11 | + | + | − | CBLH-V | Variant | 20 | M | 60 | 62e | 62e | + | |

| 13 | 12 | + | + | + | CBLH-V-MCM | DWM (S) | 32 | M | 65 | 62e | 62e | + | |

| 14 | 13 | + | − | CBLH-V | DWM (M) | 13 | F | 89e | 89e | 89e | |||

| 15 | 14 | + | + | CBLH-V | Variant | 14 | F | 96 | 96e | 98 | + | ||

| 16 | 15 | + | +d | + | CBLH-V | DWM (M) | 24 | M | 75e | 75e | 75e | ||

| 17 | 16 | + | + | + | CBLH-V-MCM | Variant | 18 | F | 90e | 80e | 90e | + | |

| 18 | 17 | + | + | + | CBLH-V-MCM | Variant | 20 | F | 75e | 75e | 75e | ||

- Abbreviations: 4V, 4th ventricle; CBLH-V-MCM, vermis predominant cerebellar hypoplasia with mega-cisterna magna; CBLH-V, vermis predominant cerebellar hypoplasia; DWM (C), Dandy-Walker complex; DWM (S), Dandy-Walker syndrome; FIG, images shown in Figure 1; FIQ, full scale IQ; HEM, cerebellar hemispheres; MCM, mega-cisterna magna; Our DX; our classification of the cerebelar malformation; PF, posterior fossa; PIQ, performance IQ; Pub DX, previously published classification of the cerebellar malformation; REF, original reference; Variant, Dandy-Walker variant; VIQ, verbal IQ.

- a Our imaging diagnosis.

- b Published imaging diagnosis.

- c Age at diagnosis (mean 21.44 years).

- d Mildly asymmetric cerebellar hemispheres.

- e Estimated IQ.

| Patient | Premorbid educational disturbance | Visuospatial distortion | Memory impairment | Attention deficit | Sleep disturbance | Speech disturbance | Aggression unprovoked | Psychosis versus schizophrenia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | + | + | + | + | Psychosis | ||

| 2 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | Psychosis |

| 3 | + | + | + | + | Psychosis | |||

| 4 | + | + | + | + | Psychosis | |||

| 5 | − | + | + | + | Psychosis | |||

| 6 | + | Schizophrenia | ||||||

| 7 | − | + | + | Psychosis | ||||

| 8 | − | Psychosis | ||||||

| 9 | + | Schizophrenia | ||||||

| 10 | + | + | + | + | Psychosis | |||

| 11 | + | + | + | + | + | Schizophrenia | ||

| 12 | + | + | + | + | Schizophrenia | |||

| 13 | + | Psychosis | ||||||

| 14 | − | + | + | + | + | Schizophrenia | ||

| 15 | + | Psychosis | ||||||

| 16 | + | + | + | + | Schizophrenia | |||

| 17 | + | + | + | + | + | Psychosis | ||

| 18 | + | + | Schizophrenia |

We next assessed for developmental delay or intellectual disability (ID). Many of the reports provided data on Full Scale (FIQ), Verbal (VIQ), and Performance (PIQ) intelligence quotients. When a value was reported, we included the reported value in Tables 1a and 1b. In the absence of a reported FIQ, VIQ, or PIQ, we categorized intellectual disability based on information available in the clinical description. These categories included profound (0–24), severe (25–39), moderate (40–54), mild (55–69), and borderline (70–79) ID, plus low-average (80–89) IQ. As it is more difficult to diagnose psychosis or SCZ in individuals with moderate or severe intellectual disability, we assumed that the reported cases would be less likely to meet the criteria for moderate or severe ID. Because of this, we assigned the less severe possible disability level when the available data was ambiguous. We then calculated FIQ, PIQ, and VIQ averages by taking the middle value of the IQ range for each category. We also calculated an adjusted mean FIQ, PIQ, and VIQ value after excluding the outlier IQ values of patient 8 (Case 2; Gan, 2012).

The psychiatric disorder was described as undifferentiated psychosis (atypical, refractory, or not otherwise specified), SCZ or SCZ-like. Descriptions of the cerebellar abnormalities were largely non-specific, and the figures and figure legends were limited. This led us to independently analyze the brain images provided in figures to supplement the text descriptions, focusing on posterior fossa features including CBLH (diffuse vs. vermis-predominant and symmetric vs. asymmetric), posterior fossa enlargement also designated mega-cisterna magna, and enlargement of the fourth ventricle. To help assess genetic versus non-genetic etiology, we looked for non-genetic factors predisposing to CBLH such as extreme prematurity and twinning, and brain imaging signs previously associated with non-genetic factors including periventricular nodular heterotopia, cerebellar asymmetry, cerebellar clefts, and classic Dandy–Walker malformation.

3 CLINICAL REPORT

LR21-436. Our proband is a 17-year-old male with CBLH-V who has been hospitalized numerous times for psychosis beginning at 11 years. He was born at 34 weeks gestation after a pregnancy complicated by severe pre-eclampsia and maternal HELLP syndrome. By 8 months, he was found to have visual impairment with strabismus, amblyopia, and intermittent presbyopia requiring prism glasses. He also had mild hypotonia, delay in both fine and gross motor skills and deficient social skills including poor eye contact, although initial screening for autism was negative at 9 months. He had typical early language development and spoke his first sentence at 2 years. He was referred for physical therapy.

From about 5 years, his parents noticed frequent impulsive and anxious behaviors and he began having frequent toileting accidents. He had a neuropsychiatric assessment at 9 years and was diagnosed with ADHD. At 10 years (fourth grade), he began having new problems with writing and began “hearing voices.” At 11 years, he had rapid progression of puberty and his psychiatric symptoms worsened to include visual and auditory hallucinations, paranoia, difficulty in school, depression with suicidal ideation, mania, lack of sleep, and grandiosity, which resulted in his first hospital admission for psychosis requiring initiation of antipsychotic medication.

Over the next 7 months, he was admitted to an inpatient mental health unit on four separate occasions for psychosis. His psychotic episodes were characterized by daily self-talk, anxiety, confusion, and periodic rage and aggression. He was placed on a regimen of antipsychotic medications including clonazepam, haloperidol, quetiapine, and valproic acid with mild improvement in symptoms. At 12 years, he had further decline in his ability at school with daily psychosis, paranoia, and mood and behavior difficulties. He was diagnosed with Lyme disease at 14 years and was treated with pulsed lactated ringer and intravenous ciprofloxacin. His psychosis improved following treatment for Lyme disease, but he continued to have psychosis, aggression, anxiety, and confusion. He was diagnosed with autism at 16 years and a Weschler adult intelligence scale at 17 years found a composite FIQ of 69, verbal IQ of 96, working memory of 77, and processing speed of 50. PIQ was not reported since visual challenges meant he was unable to complete portions of the test, but based on the clinical description and performance on working memory and processing speed tests, we estimate a PIQ of 62. Serial brain MRI studies between 11 and 16 years were initially reported as normal. However, subsequent re-review noted mild CBLH primarily involving the vermis.

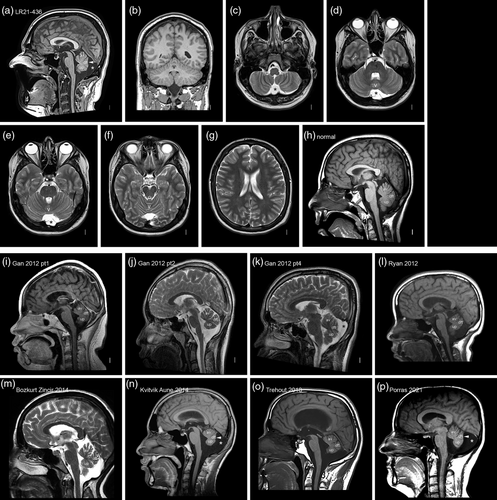

In our review, brain MRI at 16 years shows a mildly small cerebellar vermis (with significantly reduced anterior–posterior diameter) that was most severe in the posterior (lower) vermis, and mildly enlarged posterior fossa (Figure 1 and Figure S1a,b). No change in the appearance of the cerebellum was seen between 11 and 16 years (Figure S1a,b). Quantitative measurements were obtained compared to reference intervals (Figure S1c) (Jandeaux et al., 2019). Height of the vermis (H-V) was 4.41 cm (~25th percentile), anterior–posterior diameter of the vermis (APD-V) was 1.90 cm (<3rd percentile), anterior–posterior diameter of the midbrain-pons junction (ADP-MP) was 1.03 cm (~10th percentile), and the anterior–posterior mid-pons diameter (ADP-P) was 1.95 cm (3rd percentile). At last report, he continues to have a range of neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric symptoms including psychosis, sleep disturbance with significant night sweats, poor coordination with a wide-based gait, attention deficit, and aggression. Whole-exome sequencing was performed with no causal genes identified and he had a normal SNP-based chromosomal microarray.

4 RESULTS

We reviewed clinical and brain imaging data for 18 individuals from 15 reports (Bozkurt Zincir et al., 2014; Buonaguro et al., 2014; Dawra et al., 2017; Ferentinos et al., 2007; Gama, 2019; Gan et al., 2012; Kvitvik Aune & Bugge, 2014; Langarica & Peralta, 2005; Papazisis et al., 2007; Porras Segovia et al., 2021; Rohanachandra et al., 2016; Ryan et al., 2012; Trehout et al., 2019; Turner et al., 2001; Williams et al., 2016). The developmental and psychiatric data were often detailed, describing undifferentiated (unlabeled) psychosis in eight, SCZ in six, and SCZ-like features in three individuals. The same reports described the cerebellar malformation as Dandy–Walker “variant” in seven, Dandy–Walker “syndrome” in three, Dandy–Walker malformation in two, Dandy–Walker-like in one, posterior fossa arachnoid cyst in one, and mega-cisterna magna in three individuals.

However, the imaging descriptions consistently lacked key details and the figures provided were often suboptimal, with sagittal images often off-midline and axial images selected too low in the posterior fossa to judge the size of the cerebellum. Further, the now outdated term Dandy–Walker “variant” was first used when only low-resolution CT scans were available and to this day has no accepted inclusion or exclusion criteria. With far better imaging now widely available, this term should not be used to describe any cerebellar malformation. Similarly, the term “mega-cisterna magna” has been used inconsistently.

Adding our proband to data on the reported individuals, the average age of onset of psychosis was 21.4 years (range 11–34 years). An equal distribution of males (n = 9, 50%) and females (n = 9, 50%) was reported. The literature focused largely on the psychiatric phenotype of these individuals, including hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, suspicions, and inappropriate affect. Over one third (n = 7, 38.9%) were diagnosed with SCZ. We also identified several common neuropsychiatric findings among this subset of individuals. These included visuospatial distortion (n = 5, 27.8%), memory impairment (n = 8, 44.4%), attention deficit (n = 12, 66.7%), speech disturbance (n = 9, 50%), aggression (n = 10, 55.6%), and sleep disturbance (n = 5, 27.8%). Sleep disturbance was unspecified in multiple individuals, but for those where the sleep disturbance was specified, deficits in both sleep onset and sleep maintenance were described.

The cohort demonstrated a consistently decreased IQ, with average full-scale, performance, and verbal IQs all in the borderline intellectual disability range at 74, 72.4, and 76.5, respectively (all adjusted by removing Gan, 2012; Case 2) due to above average intelligence (Gan et al., 2012). All other subjects had intelligence quotients in the low-average, borderline, or mild intellectual disability range. No individuals had moderate, severe, or profound intellectual disability based on FIQ scores.

We also analyzed brain imaging from our proband (age 16) and 17 individuals (age 13–54) from 14 papers over the past 15 years. All individuals had posterior vermis predominant CBLH-V and the majority (n = 15, 83.3%) had normal-sized cerebellar hemispheres. In those with small cerebellar hemispheres (always mild), the reduced size was symmetric except for subtle asymmetry in a single individual (Trehout et al., 2019). Most (n = 13, 72.2%) had normal posterior fossa size, while 5 (27.8%) had borderline or mildly enlarged posterior fossa, sometimes called “mega-cisterna magna.” Several individuals reported with mega-cisterna magna appeared to have normal-sized posterior fossae with a prominent fluid collection that we attribute to the reduced size of the vermis. Detailed imaging in our proband and limited imaging in the reported individuals showed no evidence of cerebellar cleft, heterotopia, or cerebellar injury and no reports of individuals with extreme prematurity, twinning, or other documented prenatal injury. None of the 18 subjects met the criteria for classic Dandy–Walker malformation (Aldinger et al., 2019; Haldipur et al., 2021; Whitehead et al., 2022).

5 DISCUSSION

Review of our proband and 17 additional affected individuals reported over the past 15 years suggests a consistent pattern of psychiatric, neurodevelopmental, and brain imaging findings, with the latter comprising posterior vermis predominant cerebellar hypoplasia with normal or mildly small hemispheres and occasionally borderline to mild enlargement of the posterior fossa (cisterna magna). The consistency in the pattern of psychosis-associated CBLH-V that we found is not reflected in the actual reports, which use a variety of labels. This inconsistency reflects the broad inconsistency in the literature as a whole regarding cerebellar malformations. However, recent work by the senior author and others has begun to make some sense of the variability found among cerebellar malformations. The evidence regarding an association between antipsychotic medication and reduction in brain volume is mixed, but the reduction reported is global and not specific to the cerebellum (Moncrieff & Leo, 2010). Appearance of the cerebellum was stable in our proband between 11 and 16 years, and the literature we reviewed did not describe changes in brain volume over time. Future studies may benefit from serial and quantitative assessment including volumetric evaluation or 2D measurements of the cerebellum to further elucidate a possible association.

A re-examination of human cerebellar development using fetal samples demonstrated that the rhombic lip, the source of a large majority of cells in the cerebellum, persists far longer in human development than in other mammals examined including primates (macaque). In humans, the rhombic lip internalizes and is separated from the cerebellar ventricular zone by a rich vascular bed that is not found in lower primates or other mammals (Haldipur et al., 2019). This structure likely accounts for the many reports of cerebellar and posterior fossa hemorrhage in fetuses, mostly in the third trimester as well as the frequent cerebellar bleeds seen in extremely premature infants.

Our recent work identified two prenatal risk factors associated with non-genetic CBLH including extreme prematurity and twinning, and at least four brain imaging-based risk factors including periventricular nodular heterotopia (in the cerebral hemispheres), marked cerebellar asymmetry, cerebellar clefts, and (most remarkably) classic Dandy–Walker malformation. And as expected, we found the opposite among genetic forms of CBLH including symmetric CBLH, absence of cerebellar clefts, absence of periventricular nodular heterotopia, and only rare examples of classic Dandy–Walker malformation. The pattern of posterior vermis predominant CBLH observed in most reported subjects with psychosis or SCZ-associated CBLH fits well with the pattern observed with genetic forms of CBLH. So too does the frequent association with intellectual disability as the IQ in this cohort is shifted downward by almost 20 points (Tables 1a and 1b).

Several common copy number variants, especially deletion 22q11.2 have been associated with an increased risk for neurodevelopmental problems including psychosis and SCZ, mild intellectual disability, and attention deficits. Some have also been associated with structural brain changes, but as far as we have seen only deletions in 22q11.2 and 22q13.3 have been associated with cerebellar hypoplasia (Aldinger et al., 2013; Schmitt et al., 2023). Our patient had normal whole exome sequencing and SNP-based chromosomal microarray, and no genetic testing was performed in any of the 17 previously reported individuals.

Based on the consistent association with neurodevelopmental disabilities, the posterior vermis-predominant (and symmetric) cerebellar hypoplasia, and the paucity of prenatal and imaging risk factors, we hypothesize that the combination of psychosis or SCZ and CBLH-V comprises a homogeneous endophenotype of individuals with psychosis or SCZ that is likely to have an underlying genetic basis. This is a hypothesis that needs to be tested. As no reliable targeted panel of genes associated with CBLH has been defined, we recommend trio-based whole exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in this disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank our proband and his family for sharing his information with us. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health under the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) grant number 5R01NS050375 to William B. Dobyns.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.