Biallelic GTF2IRD1 variants in brothers with profound neurodevelopmental disorder: A possible novel disorder involving a critical gene for Williams syndrome

Abstract

GTF2IRD1, a gene on chromosome 7 which encodes a transcription factor, is of significant clinical interest due to its heterozygous loss as part of the classical deletion associated with Williams–Beuren syndrome (WBS). However, biallelic variants in GTF2IRD1 alone as part of an autosomal recessive disease have not been previously reported. Here, we present two full brothers with variants in trans of GTF2IRD1 at c.1231C > T (p.Arg411Trp) and c.2632C > G (p.Leu878Val). A detailed clinical phenotype is described, which includes severe neurodevelopmental disability, facial dysmorphology, and pectus excavatum. Importantly, out of eight full siblings, only these two brothers harboring both variants in trans present with the profound described phenotype. We present the possibility that these brothers represent the identification of a new syndrome characterized by biallelic variants in GTF2IRD1, which may also have important implications for the molecular etiology of WBS.

1 INTRODUCTION

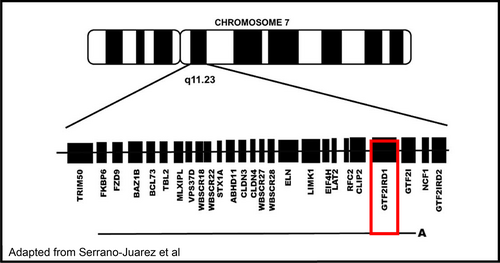

Williams–Beuren syndrome (WBS) is a well-recognized deletion disorder characterized by a 1.5–1.8 mB deletion on chromosome 7 involving 26–28 genes (Figure 1).(Morris, 1999; Pober, 2010) Clinically, patients present with a wide variety of phenotypes, including distinctive craniofacial dysmorphology, growth failure, arteriopathy, and endocrine abnormalities. Individuals with WBS have a specific neurocognitive profile including an overly friendly personality and relative strengths in verbal communication with intellectual disability and challenges in visuospatial construction. Much work has been done in an attempt to identify the critical region responsible for these various characteristics of WBS. Rare families with partial deletions of the WBS region and a number of mouse models have been instructive in this endeavor. Single gene disorders within this region would provide further important information.

Here, we present two full brothers with biallelic variants of GTF2IRD1 in the context of a multisystem disorder. Both variants are currently classified as variants of unknown significance, but have concerning molecular properties in that they are not found in large population cohorts, one of two is predicted by in silico modeling to have deleterious effects on protein structure/function (c.1231C > T), and, most importantly, only these two brothers (out of eight siblings) with these biallelic variants have the described phenotype, while other family members harboring neither or only one variant or the other do not. Their clinical presentation is characterized by severe neurodevelopmental disability involving inability to function independently as adults requiring constant supervision. There is a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in both siblings, epilepsy in the younger sibling and history of absence seizures as a young child in the older sibling, a brain mass in the older sibling concerning for focal cortical dysplasia versus low-grade glioma, mild facial dysmorphology and plagiocephaly, and pectus excavatum. Hypersociability and relative strength in verbal communication, hallmarks of WBS, are not present in these patients, who have profoundly limited communication and poor eye contact. Although functional studies need to be performed in order to confirm the deleterious nature of these variants, we present the possibility that these brothers represent the identification of a new syndrome characterized by biallelic variants in GTF2IRD1.

2 CLINICAL REPORT

2.1 Older sibling, clinical description

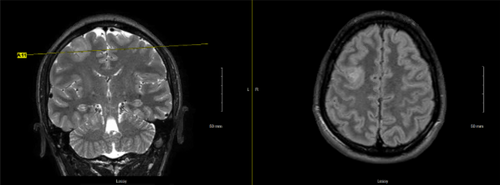

The older affected brother was the first child of nonconsanguineous parents. He was born at 35 weeks gestational age and was noted to have had a difficult delivery. In early childhood, he was noted to have a history of severe developmental delay, absence of seizures from ages 3 to 4, and was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. He presented to our care at age 24 due to his neurodevelopmental delays and history of seizure activity, with concerns for new seizure activity as well due to episodes of arm tightening and an abnormal sleep pattern characterized by poor nighttime sleep and brief 15-min naps throughout the daytime. Although an admission for video EEG monitoring ultimately did not detect any seizure activity, a brain MRI was performed and was notable for an indeterminate T2 hyperintense right frontal lobe lesion, measuring 2.5 × 2.3 × 3 cm (Figure 2). The most likely etiology was thought to be a low-grade glioma versus focal cortical dysplasia. A follow-up MRI performed 6 months later revealed an unchanged lesion, as well as a focus on hypoenhancement of the neurohypophysis. Dedicated pituitary imaging was recommended, but has not yet been performed. Endocrinology evaluated due to this finding as well, but did not find evidence of posterior pituitary dysfunction, such as polyuria or nocturia.

Additional past medical history is notable for exotropia requiring surgery at ages 18 months and 4 years, and a visit to Ophthalmology at age 17 noted bilateral hyperopia with astigmatism, and right-sided amblyopia, for which corrective lenses were prescribed. Additional surgical history includes a surgically corrected hydrocele and placement of bilateral myringotomy with pressure equalization tubes.

On our examination, craniofacial dysmorphology includes positional plagiocephaly, a round face, prognathia, a thin upper vermilion border, anisocoria, and ear anomalies, with discrepant size between the ears, and with a posterior pinna divot present on both ears (Figure 3). Additional pertinent physical examination findings include a pectus excavatum, mild scoliosis, excessive moles, and groin freckling. He makes minimal eye contact, says no intelligible words, performs repetitive behaviors, and will react to his name but not use any words or gesture to answer questions.

2.2 Younger sibling, clinical description

The younger affected brother was the second child of the same parents. He was born at 40 weeks gestation at a weight of 7 pounds 6 ounces. There were no pregnancy complications. His early childhood is significant for severe developmental delay and a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder at the age of 2 years. At around age 13 years, he experienced behavioral changes, described as increased outbursts, increased anger, and regression in the areas of language, handwriting, and learning. He has also been diagnosed with intractable epilepsy, which has been confirmed during video EEG admissions, and for which he takes anti-epileptic medications. His EEG demonstrates likely generalized onset of tonic–clonic seizures, although there has been some question of brief, bi-frontal initiation of onset. Sugar was identified as a possible trigger. He additionally has episodes of inappropriate laughing, which have been questioned as possible seizure activity, but have not been confirmed on EEG. He presented to our care at age 18 due to his diagnosis of autism and epilepsy without an identified molecular etiology. He had an MRI performed that was normal without findings to explain his clinical epilepsy.

Additional past medical history is notable for increased thirst with polydipsia, as well as a history of exotropia which has been surgically corrected. He was seen by ophthalmology at age 17 and was noted to have bilateral hyperopia with astigmatism. He has also had an echocardiogram at age 22 which demonstrated normal structure and function.

Physical examination is notable for plagiocephaly, a long and narrow face, pectus excavatum, thoracic and lumbar scoliosis, and excessive moles (Figure 3). In the clinic, he makes no eye contact, can state his own name and a few tangential comments but with few words, performs echolalia, and engages in body-rocking.

2.3 Genetic testing

Both affected brothers and their mother had fragile X testing performed that was normal, although no records were available for us to view. Both affected brothers also had a microarray performed shortly after presenting to our care, which were normal as well. Exome sequencing was ultimately performed on a clinical basis through the GeneDx laboratory, and identified biallelic variants in GTF2IRD1 in both affected brothers—a paternally inherited heterozygous variant c.1231C > T (p.R411W) as well as a maternally inherited heterozygous variant c.2632C > G (p.L878V). Further testing of each of the additional six living siblings was performed and is detailed in the “Family History” below, but did not identify additional individuals with biallelic variants outside of these two affected brothers. Neither variant is present in large population cohorts. The c.1231C > T variant, but not the c.2632C > G variant, is predicted to have a deleterious effect on protein structure/function.

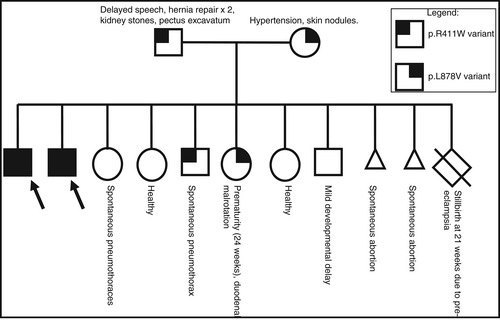

2.4 Family history

The neurodevelopmentally typical mother is heterozygous for the GTF2IRD1 p.L878V variant. She has hypertension and skin nodules. In addition to her eight living children, she has had two miscarriages and one pregnancy complicated by pre-eclampsia end in a stillbirth at 21 weeks gestational age. The father, who is also neurotypical, is heterozygous for the GTF2IRD1 p.R411W variant. He has a history of delayed speech, two hernia repair surgeries, back pain, kidney stones, and a mild pectus excavatum. Both parents are of high-level intelligence.

The brothers reported herein are the eldest children in the family. There are six younger siblings. After the brothers are two sisters who do not have either variant detected in GTF2IRD1. The older sister has a history of spontaneous pneumothorax, while the younger sister is healthy. After these sisters is a brother who is heterozygous for the p.R411W variant, and also has a history of a spontaneous pneumothorax. Next oldest is a sister who is heterozygous for the p.L878V variant. She was born prematurely at 24 weeks gestational age and has a history of duodenal malrotation; she is reportedly doing well from a neurodevelopmental perspective in context of her prematurity and does not have the profound problems her older brothers have. The youngest two siblings, a sister then a brother, both have no variants detected in GTF2IRD1. The sister has migraine headaches while the brother has mild developmental delay primarily in the area of expressive language, although is progressing well with speech therapy. This pedigree, including genotype at GTF2IRD1, is shown in Figure 4.

On the mother's side of the family, mother's mother had a myocardial infarction at age 45. She was noted to have total occlusion of her left anterior descending artery and was told her coronary artery was “tortuous” and that she had a congenital curve in her aorta. Her health history is also significant for scoliosis, glaucoma, osteoporosis, history of knee surgery, and being born as a “blue baby”. Mother's father died at age 22 from reticular cell sarcoma in his gastrointestinal tract. Mother has a brother with hypertension and a hernia. Mother has an uncle with mitral valve prolapse and unknown cancer type, who also has a daughter with thyroid cancer and a grandchild with spinal and eye cancer. Mother has a sister who is healthy.

On father's side of the family, father was adopted and information is limited. Father's father died at age 45 from a T-cell malignancy. The brother with a recurrent pneumothorax had a separate genetics evaluation and given the musculoskeletal connective tissue findings on both sides of the family, he had a connective tissue genetics next-generation sequencing panel completed (including sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis) and echocardiogram; both were normal.

3 DISCUSSION

Gene dosage disorders involving GTF2IRD1 are well characterized, both through heterozygous loss as part of the WBS classical deletion as well as through duplication in the less common 7q11.23 duplication syndrome. However, involvement of GTF2IRD1 as part of a single gene disorder involving biallelic variants with an autosomal recessive phenotype has not, to our knowledge, been previously described. Two research studies utilizing exome sequencing have identified single nucleotide variants in GTF2IRD1 in individuals with autism and schizophrenia, respectively. Sanders et al. identified an individual with autism who had a single missense variant at c.1942A > G, although it is important to note that this individual also had a 7q11.23 duplication on the same chromosome as the missense variant, which has been associated with autism itself (2012). Similarly, Ambalavanan et al. identified an individual with child-onset schizophrenia with a single missense variant in GTF2IRD1 at c.1069C > T, p.Arg357Cys (2016). However, in both of these patients only one allele of GTF2IRD1 was affected, and it is unclear what effect, if any, these missense changes had on the overall phenotype of these patients with autism and child-onset schizophrenia.

Although it is possible that the described patients in this report represent the identification of a new syndrome in its own right, it is also likely that this identification may lead to further understanding of WBS, in which much work has been done in the area of genotype–phenotype correlation. Genotype–phenotype mapping studies of patients with partial deletions of the WBS region, as well as mouse models, have narrowed in on GTF2IRD1 and GTF2I as key genes responsible for the neurocognitive profile of WBS (Kozel et al., 2021). A small number of patients have been identified with deletions localized to the telomeric end of the classical deletion region, including both GTF2IRD1 and GRF2I, but sparing ELN and other proximally located genes (Alesi et al., 2021; Edelmann et al., 2007). Phenotypes in these patients have included significant overlap with the cognitive profile of WBS, including impaired visuospatial ability, developmental delay, excessive non-social anxiety, hypersocial behavior, autistic features, and, in some, characteristic facial features associated with WBS. However, in each of these cases, additional genes downstream of the classical WBS deletion region were also involved, some of which have been independently implicated in neuropsychological phenotypes, somewhat complicating the interpretation. Even more relevant to the current case, a separate subset of patients have been identified with deletions which include GTF2IRD1 but spare GTF2I (Antonell et al., 2010; Broadbent et al., 2014; Dai et al., 2009; Karmiloff-Smith et al., 2012; Tassabehji et al., 2005). A deletion which included only the proximal region classically involved in WBS, up to and including GTF2IRD1 and which therefore spared the downstream GTF2I, was identified in a female reported to have delayed language acquisition, impaired visuospatial performance, and a socio-cognitive profile similar to the typical profile in WBS, although each in general to a lesser degree than seen in typical WBS patients (Broadbent et al., 2014; Karmiloff-Smith et al., 2012; Tassabehji et al., 2005). A second patient with a similar deletion including GTF2IRD1 but not GTF2I did not have delayed language acquisition or overly social behavior, but did have facial features characteristic for WBS and deficits in visual–spatial construction, although again not to the degree seen in classical WBS (Dai et al., 2009). Conversely, a smaller deletion which also included GTF2IRD1 but not GTF2I was identified in a family with at least eight affected members who were described to have an outgoing personality, mild cognitive deficits, and some characteristic facial features, but with no deficits in visuospatial construction (Antonell et al., 2010). While it is clear that GTF2IRD1, in conjunction with GTF2I and possible other genes, plays a critical role in various aspects of the WBS neurocognitive profile, these conflicting reports regarding effects on visuospatial construction and sociability highlight that genotype–phenotype assessment in the neurocognitive profile of WBS remains incomplete at this time. In addition to the rare patients described above with partial deletions involving the WBS critical region, a multitude of mouse models have been developed which selectively interrogate one or both of GTF2IRD1 and GRF2I. Mouse models in which GTF2IRD1 specifically has been disrupted, in both a heterozygous and biallelic fashion, have variably recapitulated portions of the WBS neurocognitive profile, including increased anxiety, increased sociability, and impaired motor coordination depending on the model utilized (Howard et al., 2012; Schneider et al., 2012; Young et al., 2008). Most recently, Kopp et al generated mice with homozygous GTF2IRD1 variants, alone or in combination with disruption of GTF2I, and interestingly demonstrated that disruption of GTF2IRD1 alone was sufficient to generate significant behavioral anomalies in mice, with the addition of GTF2I disruption only marginally altering the phenotype (Kopp et al., 2020).

In summary, we present two brothers with biallelic variants in GTF2IRD1 and describe their severe neurodevelopmental and multisystemic phenotype. Although functional studies have not yet been performed on these variants, biallelic disruption of GTF2IRD1 alone in murine models has been shown to cause many symptoms associated with the WBS neurocognitive profile. Additionally, in the family described in this report, it is striking that out of eight full siblings, only these two brothers harboring both variants in trans present with the described profound phenotype. It is possible that these brothers represent the identification of a novel disorder characterized by autosomal recessive inheritance with biallelic variants in GTF2IRD1 and we hypothesize that further study of this disorder may lead to insights into the pathophysiology of WBS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are immensely grateful to our patients and their families for their assistance with this report.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest in publishing this report.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.