Family perspectives on gaps in health care for people with Down syndrome

Funding information: Bryan Summer Research Program, Grant/Award Number: Not Applicable

Abstract

Patients with Down syndrome (DS) have significant specialized healthcare needs. Our objective was to understand what families of patients with DS perceive to be the most pressing gaps in health care, barriers to attendance at a DS specialty clinic, and what they thought a specialty healthcare clinic for people with DS ought to include as part of the clinical package. A qualitative survey was distributed nationally through the online platform SurveyMonkey. We divided respondents into two groups: those who attended a DS specialty clinic (n = 141) and those who did not (n = 100). Data were cleaned and analyzed in RStudio 3.6.3. Results demonstrate that families value mental health services, therapies (e.g., physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy), developmental specialists, dietitians, and educational advocates. Lack of clear advertisement, especially within low-income communities, a lack of awareness of DS specialty clinics, and travel time to clinics constituted significant barriers to care. These findings are arguably of benefit to those who direct DS specialty clinics because they offer direction for resource allocation in a time of increasing healthcare costs and financial scrutiny.

1 INTRODUCTION

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common chromosomal disorder with an estimated 5000 babies born annually (Parker et al., 2010) and approximately 210,000 individuals with DS living in the United States in 2010 (De Graaf, Buckley, Dever, et al., 2017; De Graaf, Buckley, & Skotko, 2017; de Graaf et al., 2019). Although DS is commonly associated with intellectual disability, those with DS also have common health problems such as obstructive sleep apnea and difficulty with airway management, congenital heart defects, pulmonary hypertension, hearing loss, thyroid disease, celiac disease, and an increased risk of childhood leukemia (Bull, 2011, 2020; Esbensen, 2010). New medical technologies have contributed to a remarkable increase in life expectancy from 10 years of age in the 1960s–1970s to 60 years of age in 2007 (Bittles et al., 2007; Glasson et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2002).

Published guidelines provide comprehensive recommendations that enable individuals with DS to achieve their potential (Bull, 2011; Capone et al., 2018). However, Eaves et al. (1996) found that only 50% of parents are aware of DS-specific guidelines and, of these parents, 55% believed the primary care physician was responsible to ensure compliance. This is often not the case (Jensen et al., 2013). Evidence suggests that attendance and screening at a DS specialty healthcare clinic helps children, adolescents, and adults with DS receive needed diagnoses and treatment that are often not provided at a general practitioner's office (Skotko et al., 2013).

The need for multidisciplinary teams to improve outcomes in chronic conditions is well-documented (Wagner et al., 2001). In DS specialty care clinics, the multidisciplinary team of specialists seeing a patient with DS might include a physician, dietitian, speech therapist, and a social worker (Massachusetts General Hospital, 2021). DS specialty clinics increase effectiveness of care: although primary care physicians might only see one child with DS in a 37-year period, these multidisciplinary care teams specializing in DS may see several hundred patients in a single year (Eaves et al., 1996; Global Down Syndrome Foundation, 2021). Referrals to other specialties are frequently arranged (Global Down Syndrome Foundation, 2021; Massachusetts General Hospital, 2021).

Currently, there are 71 DS specialty care clinics in 34 states (Global Down Syndrome Foundation, 2021; NDSS, 2021). There are limitations to the current DS specialty clinic model. The location of DS specialty clinics and associated travel times to clinics can present a significant barrier to attendance (Joslyn et al., 2020). Capacity limitations of specialty clinics for DS add additional challenges (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021). In 2021, Santoro et al. found that 3%–5% of the eligible adult population can be served at DS specialty clinics.

Few studies have inquired about family perspectives on their experience at a DS specialty clinic. Santoro et al. note that their analyses do not consider the perspective of individuals with DS or their families because these data were not available. They stated that it would be valuable to learn what services patients and their families viewed as “must-haves” in the clinical setting (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021).

We began this study to learn more about the experience and barriers for caregivers of individuals with DS at specialty clinics. Using survey responses, the goal of this study is to determine: (1) family perspectives on the importance of specialty health care for their child with DS, (2) barriers to attendance at a specialty healthcare clinic, and (3) gaps between family expectation of services and the services available during a clinical encounter. Overall, our study evaluated what healthcare services were rated as highly important and what barriers families faced in seeking care for their children with DS. We hope these insights will be useful to determine ways to improve the clinical model (e.g., services offered and multidisciplinary team members involved) by surveying what the current experience is from the caregiver perspective and where needs may be unmet. The results of this informational survey are important to guide future quality improvement research within existing specialty clinics and to guide centers that are considering establishing a specialty clinic for DS.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

A novel survey was created on the online survey platform (www.surveymonkey.com). The survey has a Flesch Reading Ease of 50.1 and a Flesch Kincaid Grade Level of 9.8. It was developed after 300 clinical observations in a DS specialty clinic in the Northeastern United States, consultation with a DS specialty clinic director, and a pilot study in 2018. The survey was distributed for 2 months in summer 2019 through emails and postings on social media platforms maintained by state-level nonprofit organizations, family support groups, regional chapters affiliated with The Arc, Gigi's Playhouse, and human rights offices. Roughly 235,000 people follow the organizations on social media that we contacted to disseminate the survey. The number of email recipients is unknown. There was no compensation for participation in this survey and an informed consent was included at the start of the survey. This survey did not contain any identifiable information but included open-ended questions. All individuals had the option to elect not to complete the survey. The Institutional Review Board approved the study at Simpson College under the project title “Evaluating Health Systems for People with Down Syndrome.” A copy of the survey is available in the Supporting Information Material.

2.2 Participants

Participants were required to be family members of individuals with DS in the United States. Since we were interested in families' clinical experiences or barriers to attendance, the inclusion criteria were determined based on survey responses to Questions 23, 24, 25, and 31. The participants were divided into two populations: (1) those that had attended a DS specialty clinic at least once and (2) those that had never attended a DS specialty clinic. The survey yielded 141 families who had attended a DS specialty clinic and 100 families who had not attended a DS specialty clinic. Of the families that had attended a DS specialty clinic at least once, 43% had stopped attending by the time the survey was administered.

2.3 Measures

The goals of this study were to determine (1) family perspectives on the importance of specialty healthcare for their child with DS, (2) barriers to attendance at a specialty healthcare clinic, and (3) gaps between family expectation of services and the services available during a clinical encounter. We broke the respondents into two populations: (1) families who had attended a DS specialty clinic and (2) families who had never attended a DS specialty clinic. These populations were asked different questions about their experiences with DS specialty clinics. A flowchart indicating the logic programmed into the survey is included in Supporting Information Material.

To accomplish the goals of the study, we started with a series of questions on the individual with DS. Survey questions specifically addressed how families obtained the DS diagnosis, as well as physical and mental comorbidities for the individual with DS. The number of physical comorbidities were taken from survey question 7 and the number of mental comorbidities were taken from responses to survey questions 5 and 21.

To understand family perspectives on the importance of health care for their child with DS, survey questions addressed what services families would like to see at a DS specialty clinic, how important they viewed attendance at a DS specialty clinic, and what their long-term concerns were for their child with DS. To compare desired services offered at a DS specialty clinic across the two populations in the study, we combined answers to make the services consistent. When reporting findings to survey question 25, we combined responses of psychologist, psychiatrist, and behavioralist into the category “Mental Health” and we combined responses of occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech language pathology into the category “Therapy.” We omitted responses pertaining to audiology, ophthalmology, and apraxia specialist.

To determine barriers to clinic attendance, different questions were asked of the population that attended a DS specialty clinic and the population that did not. Families that attended a DS specialty clinic were asked about their recruitment and retention at the clinic, while families who had not attended a clinic were ask questions about specific barriers to attendance. For those who attended a DS specialty clinic, we combined responses of social media and advertisement into the category “Advertisement.” For those who never attended a DS specialty clinic, we combined responses “The clinic is not taking new patients,” “The clinic has age constraints on who the clinic serves,” and “Our insurance was not accepted” into the category “Clinic Constraints.” We combined responses “There's no need to attend a clinic; my child is healthy,” “We heard bad things about the clinic closest to us,” and “Appointments take too long” into the category “Hard to Justify.” We combined responses “I didn't know DS specialty clinics existed,” “I don't know where I would find a DS specialty clinic” into the category “Awareness.”

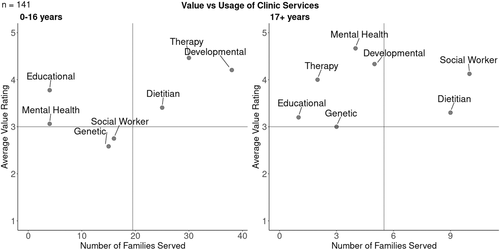

The final goal of the study was to understand gaps between a family's expectation of services offered at a clinic and their experience with these services. Survey questions were designed to understand how families who had attended a DS specialty clinic valued each service offered at the clinic and how often they utilized these services at their visits. This information was represented as two quadrant analyses, one for individuals of DS aged 0–16 years and the other for individuals of DS 17 years and older. In both analyses, the number of families who had utilized each service at least once is on the x-axis and their average importance rating is on the y-axis. On this scale, a rating of 1 was not important, 3 was somewhat important, and 5 was very important.

Questions varied from ordinal response options to closed- (multiple choice and check all that apply) and open-ended (comment) questions. Only check all that apply questions had more than one response option. We cleaned open-ended responses and added relevant responses to existing categories and created new categories based on modal responses. Means and percentages were used to summarize demographics and closed response questions. Missing data were excluded and the number of participants completing a survey question are reported where appropriate.

Data were cleaned and exploratory data analyses were performed in RStudio version 3.6.3.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

From June–July 2019, survey responses from 241 families of individuals with DS across 40 states were received (see Tables 1 and 2). Our study identified 57 DS specialty clinics in 29 states and the District of Columbia based on respondent report. A significant majority of respondents were mothers of individuals with DS. Ethnically, most of the respondents self-identified as Caucasian (85.9%). Most of the families who responded had a child under 17 years (56.4%). Respondents self-reported an average household income of $100,000–$149,999, and 22.8% indicated they had completed a master's degree. Most families in this study had attended a DS specialty clinic at least once (58.5%). The individuals with DS who were represented in this survey had an average of 4.9 distinct physical comorbidities and 0.53 mental health diagnoses (see Table 3). Most individuals with DS who were represented in this survey had received physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy between birth and age 5 (see Table 4).

| N | 241 | |

|---|---|---|

| % of Total | ||

| Relationship to individual with Down syndrome | ||

| Parent | 91.7 | |

| Sibling | 6.6 | |

| Other | 0.8 | |

| Grandparent | 0.8 | |

| No response | 0.0 | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 88.4 | |

| Male | 7.5 | |

| Other | 0.4 | |

| No response | 3.7 | |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Completed high school | 5.0 | |

| Completed some college | 15.8 | |

| Associate degree | 10.0 | |

| Bachelor's degree | 26.6 | |

| Completed some postgraduate | 5.8 | |

| Master's degree | 22.8 | |

| PhD, law, or medical degree | 7.5 | |

| Other advanced degree beyond Master's | 2.5 | |

| No response | 4.1 | |

| Family income before taxes | ||

| Below $10,000 | 2.1 | |

| $10,000–$24,999 | 2.5 | |

| $25,000–$34,999 | 2.5 | |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 7.9 | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 16.2 | |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 17.8 | |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 22.0 | |

| $150,000 or higher | 19.9 | |

| No response | 9.1 | |

| Primary language | ||

| English | 95.0 | |

| Othera | 2.1 | |

| No response | 2.9 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White/Caucasian | 85.9 | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1.2 | |

| Black/Afro-Caribbean/African American | 2.1 | |

| Native American/Alaskan Native | 0.4 | |

| South Asian/Indian American | 0.4 | |

| East Asian/Asian American | 0.4 | |

| Middle Eastern/Arab American | 0.0 | |

| Multiracial | 2.9 | |

| No response | 6.6 |

- a Three of families responded that they were bilingual with English and either Spanish, German, or American Sign Language. One family indicated that their primary language at home was Urdu.

| N | 80 | 61 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Attending clinic | % No longer attending clinic | % Never attended a clinic | |

| Region of residencea | |||

| Midwest | 48.8 | 45.9 | 38.0 |

| South | 15.0 | 21.3 | 26.0 |

| West | 12.5 | 16.4 | 21.0 |

| Northeast | 21.3 | 9.8 | 10.0 |

| No response | 2.5 | 6.6 | 5.0 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 47.5 | 54.1 | 46.0 |

| Female | 50.0 | 39.3 | 51.0 |

| Other | 0.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| No response | 2.5 | 4.9 | 3.0 |

| Age group | |||

| 0–16 | 60.0 | 47.5 | 59.0 |

| 17+ | 40.0 | 52.5 | 41.0 |

| No response | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Insurance type | |||

| Private (employee-based) | 42.5 | 47.5 | 33.0 |

| Public (Medicaid, Medicare) | 25.0 | 26.2 | 38.0 |

| Both private and public | 30.0 | 19.7 | 25.0 |

| None | 0.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| No response | 2.5 | 4.9 | 3.0 |

| Clinic experience rating | |||

| 1 (Completely unsatisfied) | 0.0 | 13.1 | NA |

| 2 | 7.5 | 11.5 | NA |

| 3 | 20.0 | 19.7 | NA |

| 4 | 27.5 | 21.3 | NA |

| 5 (Completely satisfied) | 43.8 | 34.4 | NA |

| No response | 1.3 | 0.0 | NA |

| Travel distance to clinic | |||

| 0–20 miles (0–32 km) | 38.8 | 41.0 | NA |

| 20–40 miles (32–64 km) | 15.0 | 11.5 | NA |

| 40–60 miles (64–96 km) | 11.3 | 6.6 | NA |

| 60–80 miles (96–128 km) | 7.5 | 3.3 | NA |

| 80–100 miles (128–160 km) | 3.8 | 6.6 | NA |

| >100 miles (>160 km) | 23.8 | 27.9 | NA |

| No response | 0.0 | 3.3 | NA |

- Note: The participants were divided into three populations: (1) those attending a Down syndrome specialty clinic, (2) those who stopped attending a Down syndrome specialty clinic, and (3) those that had never attended a Down syndrome specialty clinic.

- a As determined by the U.S. Census Bureau (2021) Regions and Divisions. Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont. Midwest: Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota. Wisconsin. South: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, West Virginia. West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming.

| N | 241 | 141 | 100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average # of diagnoses | Average # of diagnoses for those who have attended a clinic | Average # of diagnoses for those who have never attended a clinic | ||

| Total mental health diagnoses | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.51 | |

| Total physical health diagnoses | 4.90 | 5.11 | 4.61 |

- Note: The participants were divided into two populations: (1) those that had attended a Down syndrome specialty clinic at least once and (2) those that had never attended a Down syndrome specialty clinic. Physical diagnoses included acid reflux, airway malacia, alopecia, atlantoaxial instability, celiac disease, chronic ear infections, congenital heart defects, diabetes, Down syndrome arthropathy, duodenal atresia, folliculitis, frequent respiratory infections, Hashimoto's disease, hearing loss, Hirschsprung's disease, hypertension, hypothyroidism, iron deficiency, lactose intolerance, leukemia, otitis media, pulmonary hypertension, sleep apnea, swallowing and feeding difficulties, transient leukemia, and vision impairment. Mental health diagnoses included Alzheimer's/dementia, anxiety, autism, bipolar disorder, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia.

| N | 241 | 141 | 100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Total | % Who have attended a clinic | % Who have not attended a clinic | ||

| Physical therapy | 87.1 | 87.9 | 86.0 | |

| Occupational therapy | 90.5 | 90.8 | 90.0 | |

| Feeding therapy | 44.4 | 46.8 | 41.0 | |

| Speech therapy | 89.6 | 90.1 | 89.0 | |

| Music therapy | 22.8 | 29.1 | 14.0 | |

| Horse therapy | 15.8 | 22.7 | 6.0 |

- Note: The participants were divided into two populations: (1) those that had attended a Down syndrome specialty clinic at least once and (2) those that had never attended a Down syndrome specialty clinic.

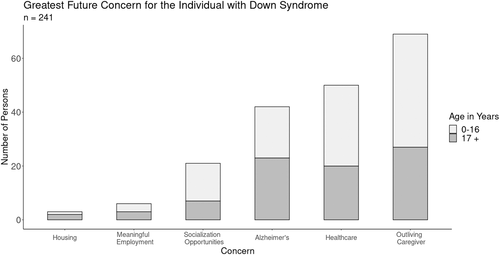

3.2 Family perspectives

All families in this study indicated their highest concern about the future for their child with DS. Most families were concerned that their child would outlive their caregiver and need access to healthcare. Families of children aged 0–16 also noted that socialization opportunities were important for the future (see Figure 1).

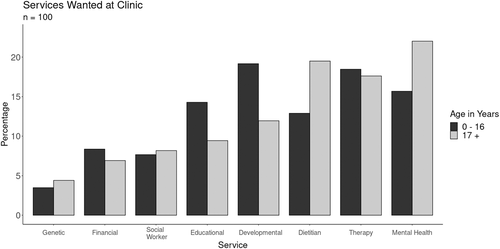

We asked families who had never attended a DS specialty clinic to rank the most important services to have in a clinic. Family members of individuals with DS ages 0–16 years reported their top three clinical services to be consultations with developmental specialists, therapists (physical, occupational, and speech), and mental health services. Family members of individuals with DS ages 17+ years viewed dietitians, therapists (physical, occupational, and speech), and mental health services as most important (see Figure 2).

3.3 Barriers to specialty clinic attendance

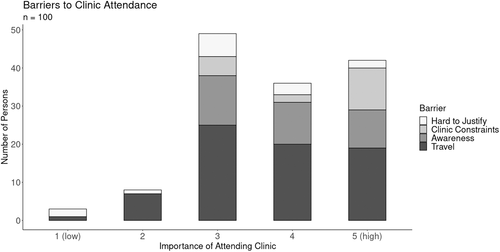

Families who had never attended a DS specialty clinic face significant barriers to clinic attendance, most notably travel time and awareness of services offered at a DS specialty clinic. Despite the barriers, these families think that attendance at a DS specialty clinic is important (see Figure 3).

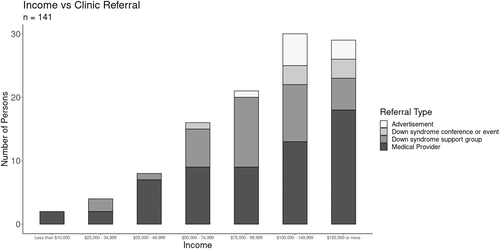

Most families who had attended a DS specialty clinic heard about these clinics through referral from their primary care physician. Families whose income was $50,000 and higher reported hearing about DS specialty clinics from advertisements/social media, a DS conference or event, a DS support group, or referral from a medical provider. Families who had an income of below $50,000 had a significantly reduced range of entrée into a DS specialty clinic and only heard of the clinics through referral from another medical provider (see Figure 4). Of the families who had attended a DS specialty clinic, only 57% continued at a clinic at the time of the survey. The families who stopped attending a clinic were not as satisfied with their clinical experience, were more likely to have a child aged 17 years older, and were not as likely to have both private and public insurance as those who persisted at a DS specialty clinic (Table 2).

3.4 Gaps in services at a specialty clinic

Families who had attended a DS specialty clinic indicated which services they utilized at DS specialty clinics and how important they viewed these services (Figure 5). If all services were utilized and highly valued by families of individuals with DS, all points in this analysis would rest in the first quadrant (upper right corner). This was the case for dietetics in both age groups. Families of individuals with DS aged 0–16 years rated mental health services and educational advocates as important, but these services were underused. Families of adults with DS aged 17+ years rated having educational advocates, therapists (physical, occupation, speech), mental health services, and developmental services as important and underused.

4 DISCUSSION

With recent advances in increasing the lifespan of individuals with DS (Bittles et al., 2007; Glasson et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2002), there is a growing need to provide clinical care to individuals with DS throughout their lifetime. While antecedent literature has demonstrated the utility of a specialty clinic for patients with DS (Skotko et al., 2013), we could find none that focused on what types of services are valued in a clinic and what barriers to care exist from the perspective of families. Our data reveal what services families of patients with DS view as most important to receive in a DS specialty clinic and therefore provide potential insight for clinics in terms of resource allocation.

4.1 Family perspectives

Families of individuals with DS want to know about the functional capabilities of their child, not just clinical details. This is supported by Khan et al. who found that mothers of children with DS in Kashmir, India listed their highest future concerns for their children as school placement, work and independent living, and the child outliving the caregiver (Khan et al., 2018). Sheets et al. (2011) found this to be true when families receive the initial DS diagnosis. They found significant differences between parent and genetic counselor responses that illustrated that parents appreciate information about abilities and potential of people with DS.

4.2 Barriers to specialty clinic attendance

Lack of clear communication of services limits care for clients of a DS specialty clinic. There is a need for clinics to (1) improve communication with physicians and (2) diversify advertisement beyond those resources allocated to physicians. Low-income families are not reached by advertisements, social media, or DS support groups and report that they access the clinics only through referral by a physician. This is consistent with findings from Eaves et al. (1996) who found that most caregivers of persons with DS felt that they were required to seek information on their own. These authors expressed a clear need for professionals and the public to be better informed regarding DS and access to care. Lee (2018) found similar results when studying health information needs for mothers of young healthy children. In this study, Lee found that US mothers preferred human sources such as doctors and nurses, while immigrant Korean mothers preferred nonhuman sources such as online communities and books. Clinics may consider allocating more resources toward advertisement in a variety of sources (physicians, specialists, online communities, etc.) in low-income and underserved communities, especially since low-income people with intellectual disabilities are broadly underserved in terms of access to health (Lazar & Davenport, 2018). More broadly, our data reveal what services families use most and are rated as highly important, demonstrating which services a clinic should be more effectively communicating to potential patients and their families.

Travel time is a second significant barrier to accessing care at a DS specialty clinic. The locations of DS specialty care clinics are concentrated in metropolitan areas, which might significantly increase travel time for some patients with DS to receive specialized care (Joslyn et al., 2020). Most specialty physician visits are made to the facilities nearest to a patient's residence, and the frequency of visits tend to decrease when facilities are farther away (Weiss et al., 1971).

4.3 Gaps in services at a specialty clinic

Families of individuals with DS value attending clinics because they found resources that enhance their child's educational opportunities, mental health, and development valuable. Several studies have found that families play a key role in implementing physical, occupational, and speech therapy programs that help children achieve milestones (Alesi & Pepi, 2017; de Graaf et al., 2019). We found that most families of individuals with DS represented in this study had early access to physical, occupational, and speech therapies (Table 4), and continued to value these services throughout the lifetime of their child with DS. Families of children with DS aged 0–16 years found their needs met with therapy services at a DS specialty clinic, while families of children with DS 17 years and older found their needs unmet. Many centers may not have been able to provide occupational, speech, or physical therapy consultation due to insurance caps, variation in costs in insurance plans, or differences in coverage between private and public insurances (Carvalho et al., 2017; Fuentes et al., 2017; Pergolotti et al., 2018; Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021; Zhang & Baranek, 2016). Santoro et al. surveyed staff at DS specialty clinics that serve adults. Their study found that staff viewed social workers, clinic coordinators, psychologists/neuropsychologists, and resource specialists as the “must-have” professionals associated with a DS specialty clinic serving adult populations (2021). There were discrepancies between resources available and desired regarding mental health services (50% responded must-have, but 7% currently have these services available) (Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021). In our study, all families who had attended a DS specialty clinic consistently reported mental health services as an unmet need in a DS specialty clinic. This may be related to gaps in clinical knowledge (Capone et al., 2018) and diagnostic overshadowing (Tassé et al., 2016) at nonspecialty clinics in which symptoms of a mental health diagnosis are attributed to DS instead of to mental illness. Insurance caps and coverage contribute to this gap in care (Nageswaran et al., 2011; Vohra et al., 2014). Given that people with DS may experience higher rates of mental illness than others with ID (Dykens et al., 2015) and that there is evidence of undertreatment of these conditions (Walker et al., 2011), it seems especially important that DS specialty clinics are prepared to offer mental health-related services. These findings suggest clinics may want to consider placing a high importance on allocating resources toward mental health care.

There are limitations to our study. We used a convenience sample to determine the families in our study. To date, there is no population-based database of people with DS and their families. Until one is created, we must use convenience samples to better understand the needs of the community. Our respondents were largely female, white, and well educated: 69% had a 4-year college degree or higher, most had some form of insurance coverage, and most had attended a DS specialty clinic (Tables 1 and 2). We know that DS naturally occurs equally in all races and ethnicities, regardless of socioeconomic status. Furthermore, it is estimated that 5%–20% of the eligible population is currently served by DS specialty clinics (Joslyn et al., 2020; Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021). When conducting computer-based survey research to a nontargeted audience, there can be many associated limitations including sampling issues, access issues, and ethical issues of online survey informed consent and verification of survey participants (Colvin et al., 2004; Nayak & Narayan, 2019; Wright, 2005). We introduced nonresponse bias as the survey was distributed blindly via a computer-based distribution method to a nontargeted population. The correct response rate is indeterminate as the actual number of eligible participants contacted is unknown. Despite the unknown response rate, participants' perspectives contribute vital information and potential insight on creating stronger access to DS specialty clinics. Experts in survey methodology argue that findings from low response rates contribute to research and that low response rates are not always a critical limitation to research (Hendra & Hill, 2019). Although the survey was translated into Spanish and French, in hopes of reaching a broader demographic, no one completed these surveys. Additional limitations of our study include recall bias in families reporting on clinical experience. This bias may limit the generalizability of study findings. Our study is not validated, and although we reviewed and revised our survey based on clinical observations and an initial survey distributed in 2018, there is potential for bias in the survey questions. It is possible that a respondent may have a differing understanding of questions than what we intended.

Future directions for this work include increasing understanding of the different models of care that are offered across DS specialty clinics, eliciting more clinician viewpoints on what services are crucial to offer to patients with DS, and understanding the communication barriers between primary care physicians and specialty care clinicians. Our study did not specifically investigate what families perceived as mental health issues in childhood and adolescence compared to the older group. A future study would be useful to learn more about these viewpoints. We also suggest survey work that elicits the opinions of adolescents with DS as to what they view as the most beneficial aspect of their clinical experience. This work was conducted before the global COVID-19 pandemic; it would be instructive to determine the impact of the pandemic on the clinical experience. This constitutes further rationale for promoting telehealth and virtual clinics such as DSC2U (Chung et al., 2021; Santoro, Campbell, et al., 2021; Santoro, Donelan, et al., 2021).

5 CONCLUSION

Additional services and communication are needed to accommodate the needs of individuals with DS in a specialty care setting. Survey of families of individuals with DS provides guidance on what services are most valuable, what barriers exist for families to attend clinic, and gaps in current clinical care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to the parents and family members of people with Down syndrome for participating in research. Thank you also to Graham Brooks, Noelie Boardman, Levi Lefebure, and Scott Oderio for their contributions with the survey dissemination and analyses. Thank you to Dr. Anne Kohler for her significant contributions to survey creation and insights from clinical observations. Thank you to Laura Cesarco Eglin, Sara Lawson, and Nicolas Rey-Le Lorier for their work translating the survey into Spanish and French. Thank you to Dr. Brian Skotko for his support and advice at multiple stages of this research project. Thank you to Simpson College and the Hal & Greta Bryan Summer Research Program that funded this project. Thank you to the referees for their work in improving the quality of this work. This project was funded internally through the Hal & Greta Bryan Summer Research Program at Simpson College. The role of the funders was to provide 8-week summer salaries and housing for Emily King and Mason Remington and summer salary for Dr. Berger. This funding body has no open access requirements.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Emily King and Mason Remington do not have any conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. Heidi Berger has a son with Down syndrome.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.