A model to characterize psychopathological features in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome

Abstract

High prevalence of behavioral and psychiatric disorders in adults with Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) has been reported in last few years. However, data are confusing and often contradictory. In this article, we propose a model to achieve a better understanding of the psychopathological features in adults with PWS. The study is based on clinical observations of 150 adult inpatients, males and females. Non-parametric statistics were performed to analyse the association of psychopathological profiles with genotype, gender and age. We propose a model of psychiatric disorders in adults with PWS based on cognitive, emotional and behavioural issues. This model defines four psychopathological profiles: Basic, Impulsive, Compulsive, and Psychotic. The Basic profile is defined by traits and symptoms that are present in varying degrees in all persons with PWS. In our cohort, this Basic profile corresponds to 55% of the patients. The rest show, in addition to these characteristics, salient features of impulsivity (Impulsive profile, 19%), compulsivity (Compulsive profile, 7%), or psychosis (Psychotic profile, 19%). The analysis of factors associated with different profiles reveals an effect of genotype on Basic and Psychotic profiles (Deletion: 70% Basic, 9% Psychotic; Non-deletion: 23% Basic, 43% Psychotic) and a positive correlation between male sex and impulsivity, unmediated by sex hormone treatment. This is a clinical study, based on observation proposing an original model to understand the psychiatric and behavioural disorders in adults with PWS. Further studies are needed in order to test the validity of this model.

1 INTRODUCTION

Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is a developmental, neuroendocrine, genetic disorder characterized by typical dysmorphic features and a variable expression of somatic, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms (Cassidy & Driscoll, 2009; Goldstone, Holland, Hauffa, Hokken-Koelega, & Tauber, 2008). Epidemiological studies estimate a PWS incidence of 1 in 25,000 births and a population prevalence of 1 in 50,000 (Whittington et al., 2001). PWS is a “contiguous gene syndrome,” resulting from an absence of expression of the paternally derived alleles of maternally imprinted genes in the q11-13 region of chromosome 15. In 70% of the cases, the cause is a paternal deletion of 15q11-q13. The deletion can be longer (Type I), shorter (Type II) (Christian et al., 1995), or a typical (Kim et al., 2012). A maternal uniparental disomy (UPD) is found in 25% of cases. In the remaining 3–5%, PWS is thought to be caused by either a defect in the imprinting centre or by a balanced translocation involving a breakpoint in 15q11q13 (Goldstone, 2004). The genetic region of PWS contains a cluster of imprinted and non-imprinted genes, and their respective contributions to the phenotypic features have not yet been clearly established (Maina et al., 2007). Recently, small deletions of the SNORD 116 gene had been shown to reproduce, albeit moderately, the entire phenotype of PWS (Bieth et al., 2014; de Smith et al., 2009; Duker et al., 2010; Sahoo et al., 2008).

Psychopathological features, including behavioral disturbances and psychiatric disorders, are now considered to be critical issues in PWS. In recent years, care of the somatic aspects of the illness has progressed due to earlier diagnosis, hormone substitution therapy, and other advances in symptom management. However, improvement of psychopathological aspects has been poor and they have become the greatest challenge to provide a better quality of life for patients and their families.

A review of previous reports in the field of psychopathology in PWS shows the existence of two main approaches: behavioral and psychiatric. Most behavioral research was performed asking relatives and caregivers to complete questionnaires in the form of checklists of adaptive and maladaptive behaviors. These inventories were created for typically developing people or adapted to a population with intellectual disability but none was specific to a PWS population. They reported a high prevalence of maladaptive behaviors even compared to people with similar intellectual disability due to other aetiologies (Clarke, Boer, Chung, Sturmey, & Webb, 1996; Dykens & Kasari, 1997; Sinnema, Boer, et al., 2011; Verhoeven, Egger, & Tuinier, 2007). Besides the typical hyperphagia, challenging behaviors commonly described in people with PWS include stubbornness, temper tantrums, skin picking, compulsiveness, mood fluctuations, and disruptive behavior (Clarke et al., 2002; Einfeld, Smith, Durvasula, Florio, & Tonge, 1999; Jauregi, Laurier, Copet, Tauber, & Thuilleaux, 2013). Behavioral disturbances have also been reported to have a different typology or severity as a function of genotype. For example, m-UPD subtype displays fewers obsessive-compulsive and ritualistic behaviors (Dykens & Roof, 2008; Milner et al., 2005) and higher prevalence of communication disturbances and social withdrawals (Jauregi et al., 2013).

The second approach is oriented to describing psychiatric comorbidities in people with PWS. The method of most of these studies is based on the use of psychiatric screening instruments, sometimes adapted to a population with intellectual disability. Usually, the informants are also the relatives and caregivers. In some cases, the assessment is performed by a clinical expert, using a structured or semi-structured interview. Their aim was the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders belonging to current nosological classifications. From this perspective, a broad array of comorbid psychiatric illnesses has been described with prevalence of up to one third of the individuals with PWS (Dykens & Shah, 2003). The most frequently cited disorders were affective disorders with or without psychotic symptoms (Sinnema, Einfeld, et al., 2011; Soni et al., 2008), atypical psychosis (Verhoeven & Tuinier, 2006; Vogels et al., 2004), obsessive compulsive disorder (Clarke et al., 2002; Wigren & Hansen, 2003), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Wigren & Hansen, 2005), and pervasive developmental or autistic-like disorder (Descheemaeker, Govers, Vermeulen, & Fryns, 2006; Dimitropoulos & Schultz, 2007). The development of psychiatric disorders in PWS is influenced by genetic, biological, and environmental factors (Soni et al., 2007).

An increased risk of developing psychotic disorders has been associated with the UPD genotype (Boer et al., 2002; Verhoeven, Tuinier, & Curfs, 2003; Vogels, Matthijs, Legius, Devriendt, & Fryns, 2003; Yang et al., 2013).

Both behavioral and psychiatric approaches lead to controversial results and do not provide an overview of the real adaptation problems of people with PWS. Thus, for example, there is no agreement on the pertinence of including PWS between autistic spectrum disorders (Dimitropoulos & Schultz, 2007) or on the traits that define the behavioral phenotype (Jauregi et al., 2013). The aim of our study is to propose a model of psychopathological aspects of PWS from a different perspective, which, beyond a descriptive listing of behavioral or psychiatric symptoms, reveals the global functioning of the persons as a parameter that determines their adaptive capacities. Thus, based on our clinical experience with almost 300 patients followed up on a regular basis, we propose a model of psychopathological features that describes four main profiles in PWS. Furthermore, we have analyzed their distribution in a large cohort of adults as well as the influence of genotype, gender, and age.

2 METHOD

2.1 Conditions of the clinical observation: Qualitative study

The proposed model is based on the extensive experience of the authors in the management of adults with PWS in a specialised centre located in the Marin Hospital of Hendaia (Basque Country- France). Created in 1999, it now has a capacity of 30 beds where adults with PWS or PWS-like pathologies stay for intervals between 1 and 3 months, usually repeated with diverse frequencies. The hospital unit belongs to the French Reference Centre for PWS and admits patients coming from all regions in France.

This unit proposes a multidisciplinary approach to the syndrome. Admissions are requested by the patient or his or her caregivers. The purpose of the stay is firstly, to assess the psychosocial and medical problems in order to define the needs of each individual and to propose a personalized management strategy. In general, the challenges are weight control, improvement of physical condition, care of medical complications, promotion of psychological well-being, and social adaptation. Furthermore, the stay provides a break for the family or everyday residential routines. The admissions are scheduled months in advance, never in response to an acute clinical situation.

Since its opening, nearly 300 patients have been admitted at least once. During the weeks that they remain in the unit, patients perform educational and therapeutic activities daily under the management of the multidisciplinary team. The first and second authors are the psychiatrist and clinical psychologist of the team. Both have been part of the project since its beginning. They are the main persons responsible for the project and they maintain a close relationship with the patients throughout their stay, as individual and group therapists. Furthermore, they lead the weekly staff meetings, prescribe the treatment and the planning of activities for each patient and deal with the relationships with external caregivers and families.

This observation status allows hypothesizing a model that accounts for the existence of different psychopathological profiles. This model is entirely based on the subjective assessment and the knowledge of the expert clinicians following a long experience with these patients. Repeated presentations and discussions of this proposal have been performed in meetings of the reference centre.

2.2 Quantitative study

We performed a study in order to quantify the prevalence of the described psychopathological profiles in a large sample of inpatients with PWS and to analyse the correlations with genotype, gender, and age. We included all subjects with a genetically confirmed diagnosis who came during the year 2014 in our PWS unit and for whom it was at least the second stay. This last criterion allowed us to be more familiar with each individual's overall functioning and not confound it with a reactive state to a first admission. Thus, our sample was composed of 150 subjects whose main characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Charateristics of the cohort | |

|---|---|

| Total | 150 |

| Gender | |

| Female/Male | 81/69 |

| Age | |

| Mean age (range) | 28.2 (18–53) |

| Median age | 29 |

| Genotype status | |

| Deletion | 99 |

| Non deletion* | 44 |

| Others** | 7 |

- * Includes confirmed UPD, genetic confirmation without deletion, and Imprinting defect.

- ** Includes translocation and genetic confirmation without more precision.

The data collection and analysis were conducted in compliance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

The procedure for assessing psychopathological profiles was as follows. At the end of the admission period, the first author (psychiatrist) proposed the inclusion of the patients in one of the four profiles. In parallel, another psychiatrist, with experience in PWS but external to the unit, performed another assessment, recording, through semi-structured staff meetings, the observations of the multidisciplinary team (psychologist, nurses, educators). This second diagnosis was based on the care team's knowledge of the patient's daily functioning during the current stay. The concordance rate for the total group reaches 73%: 63% for Basic profile, 79% for Impulsive profile, 91% for Compulsive profile, and 89% for Psychotic Profile. When diagnoses were not concordant, the discrepancies were analyzed at a later joint assessment, and a consensus was reached.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive and analytical statistics were calculated in order to compare the values of the subgroups. The χ2 test was used for comparison of percentages. Test results were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

3 RESULTS

3.1 The model: Four psychopathological profiles in people with PWS

Direct observation of a large number of patients during long time periods has led us to develop a model which classifies adults with PWS into four categories, according to their dominant psychopathological pattern: Basic, Impulsive, Compulsive, and Psychotic. These patterns were defined taking into account the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcomes as factors that determine the quality of patients’ adaptation in daily life functioning and their well-being.

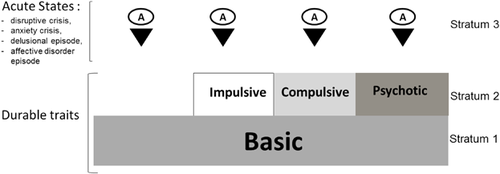

These four profiles are organized in strata, with the first stratum as the basis of the PW personality, present in all people with PWS with varying intensity and defining the Basic state.

In some cases, the characteristics defining this Basic state are the only factors limiting the adaptive capacity: these persons fall into the category of Basic profile. Sometimes, beyond this basic personality, individuals manifest additional symptoms that increase adaptive problems due to the presence of severe impulsive, compulsive, or psychotic features. These symptoms are superimposed on the basic personality as a second stratum, and the patients are then included in the Impulsive, Compulsive, or Psychotic profile, respectively. These four patterns (Basic, Impulsive, Compulsive, and Psychotic) are persistent characteristics of each individual. Beyond each pattern, acute forms of psychiatric disorders may occur in form of disruptive crises, anxiety, and depressive episodes or acute delusional states.

This model is schematically represented in Figure 1.

3.2 Characteristics of the basic profile

3.2.1 Main cognitive traits

- Mild to moderate intellectual disability.

- Rigid and perseverative thinking, difficulty adapting to changes.

- Poor understanding of metaphors and double meaning sentences.

- Time/space processing problems.

- Pragmatic deficits, difficulty making decisions, and choices.

3.2.2 Main emotional traits

- Emotional lability, immaturity, and infantilism.

- Poor social emotions, lack of empathy. Easily offended, preoccupation with “fairness.”

- Lack of inhibition, lack of shame.

- Difficulties discriminating other people's emotions and intentions.

- Preoccupation with affective and sexual themes.

- Social vulnerability, credulity (risk of physical mistreatment and sexual abuse).

3.2.3 Main behavioral traits

- Compulsive food seeking and hyperphagia.

- Other maladaptative behaviors (lying, stealing, hoarding, collectionism…).

- Arousal disorders, daytime sleepiness.

- Poor and dysfunctional social relations.

- Ritualistic behaviors.

- Disruptive crises in reaction to frustration or misunderstanding of the context.

- Skin-picking, self-mutilations.

3.3 Characteristics of the impulsive profile

- Low tolerance to frustration, not only food-related

- In reaction, severe disruptive crises with strong neurovegetative activation

- Auto- or hetero-aggressive acting out

- Little respect of social norms, conflicts with the Law without feeling guilty

- Acute feeling of injustice, hyper-sensitivity to others’ judgment

3.4 Characteristics of the compulsive profile

- Intense rituals/stereotypes that severely affect everyday life.

- Compulsive behaviors, normally without obsessive ideation or anxiety.

- Lack of awareness of the absurdity of the behavior.

- Resistance to disruption of behavior, which can trigger tantrums.

- Restricted and repetitive interpersonal interaction.

When rituals invade the person's life, hindering action, social isolation sets in, leading to an autistic-like profile.

3.5 Characteristics of the psychotic profile

- Loss of link with reality, with or without hallucinations.

- Delusional ideation may be present, poorly structured and bizarre. It is often difficult to differentiate between delusion and fabulation.

- Strange and disorganized behavior, acting out unrelated to the context.

- Dysphoria, alternating excitement, and withdrawal.

- Ambivalence, discordance between ideas and emotions.

- Negative symptoms, that is, affective flattening, alogia, or avolition.

3.6 The distribution of the four psychopathological profiles in our cohort

In Table 2, we present the distribution of our cohort in the four psychopathological profiles globally and separated by genotype, gender, age, and male sexual hormone therapy.

| Psychiatric profiles | Basic percentage (n) | Impulsive percentage (n) | Compulsive percentage (n) | Psychotic percentage (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total group | 55 (83) | 19 (28) | 7 (11) | 19 (28) |

| Genotype | ||||

| Deletion | 70 (69) | 14 (14) | 7 (7) | 9 (9) |

| Non deletion | 23 (10) | 25 (11) | 9 (4) | 43 (19) |

| p-value* | <0.001 | 0.181 NS | 0.938 NS | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Females | 63 (51) | 10 (8) | 11 (9) | 16 (13) |

| Males | 46 (32) | 29 (20) | 3 (2) | 22 (15) |

| p-value* | 0.061 NS | 0.005 | 0.108 NS | 0.496 NS |

| Age group | ||||

| 18–29 | 47 (36) | 20 (15) | 7 (6) | 25 (19) |

| 30–53 | 63 (47) | 17 (13) | 7 (5) | 12 (9) |

| p-value* | 0.068 NS | 0.896 NS | 0.963 NS | 0.07 NS |

| Sex hormone therapy (Males) | ||||

| Males non treated | 38 (15) | 33 (13) | 0 (0) | 30 (12) |

| Males treated | 59 (17) | 24 (7) | 7 (2) | 10 (3) |

| p-value* | 0,136 NS | 0,626 NS | 0,338 NS | 0,097 NS |

- * p-values from χ2 test.

- NS, Non significant. Bold values are significant (p-value ≤0.05).

4 DISCUSSION

This study aims to contribute to the knowledge of psychopathological features in adults with PWS. The method is based on clinical observation, a classic form of analysis of the reality of the patients from a semiological and phenomenological perspective. We think that this approach is pertinent to establish a first overview of a poorly defined field in which reports are often contradictory. In fact, most previous studies were oriented to screening behavioral disorders and psychiatric symptoms, using check-lists informed by caregivers or by semi-structured interviews. This approach leads to associating patterns of behavior with psychiatric categories in a population with cognitive impairment and limited insight capacities, that usually express mental states by behavioral features (Holden & Gitlesen, 2008, 2009). Thus, we can find PWS associated with different diagnoses of DSM depending on different authors, with a lack of reliability and concordant results, and not always consistent with the observed clinical reality. Furthermore, authors frequently resort to comorbid or atypical diagnoses, which may be valid from a nosological point of view but are not very relevant with a view to improving our knowledge of patients’ real needs. In fact the rating scales that have been validated for populations with intellectual disabilities have a limited utility for PWS. It would be helpful to develop a specific tool that does not currently exist.

Our approach attempts to overcome these difficulties by analyzing the psychopathological profiles from a functional perspective, taking into account patients’ overall functioning in daily skills and identifying the traits and behaviors that are the main limiting factors to their social adaptation. We believe that such an approach is justified by the very rare situation of our centre, where an experienced team can observe the daily skills of a large number of PWS patients for extended periods of time.

A weakness of this study concerns the evaluation method, based on the subjective assessment of data from clinical observations in a semi-structured form. The inclusion of subjects in any of the four proposed profiles (Basic, Impulsive, Compulsive, and Psychotic) was easily established in most cases, but in some (27%), the consensus of the evaluation team was more difficult to reach. The higher discordance found in the Basic group can be explained by the fact that patients in this group also present symptoms described in the other profiles but in more moderate way. A quantitative and subjective assessment could easily lead to divergent assessments in a first time. In some cases, the difficulty came from changes in behavior that can occur between two admission periods. Thus, some impulsive or compulsive subjects can improve those traits, reaching the level of the basic profile in successive stays, either due to the effects of drug treatment or to a spontaneous evolution. Less frequently, some patients may show an aggravation of the disorders in a second stay for different reasons. In other cases, the difficulty comes from the overlap of symptoms in two different situations. The first one is the case of compulsive subjects exhibiting disruptive impulsive reactions if thwarted in their rituals. The second is the case of compulsive profiles presenting an autistic-like functioning and traits of a psychotic structure.

The reliability of our results and the extrapolation to global PW population could be limited by factors such as recruitment bias or new approaches to early treatment of the syndrome in different countries. However, the large size of the sample and our admission policy allow us to consider that our data represent a reliable image of the reality of PWS today. The differences between genotypes are concordant with previous reports and confirm that individuals with non-deletion genotype (m-UPD) are more likely to present psychiatric disorders, especially of a psychotic type. Gender strongly influences the distribution of compulsive and impulsive profiles. Impulsivity is much higher in males, perhaps because their disruptive episodes are more challenging for the environment and, consequently, more salient in the assessment process. Our data do not support the idea of a negative effect of male sexual hormone replacement on impulsivity.

There is general consensus about the multifactorial determinism of psychiatric disorders including genetic, biological, and environmental factors. Psychiatric features in PWS must also be analyzed in similar terms. Any of them could be considered prevalent so as to be taken as a PWS phenotype. Impulsivity, compulsivity, or psychoses are not present in most cases. Only hyperphagic behavior can be considered as a behavioral phenotype. Due to other psychopathological issues, PWS is a factor that increases the risk of cognitive impairments, more likely to be considered as phenotypical: executive dysfunction, poor emotional regulation, deficit of working memory, etc. Some increased risks could be linked to genetic factors, that is, m-UPD and psychosis. In other cases, the interaction of cognitive deficits and educational, familial, and social factors could explain the presence and severity of behavioral and psychiatric disorders.

The model of four patterns of psychopathological profile in PWS allows defining a PWS individual's main weaknesses for social adaptation, guiding the design of a life project and prescribing the most effective treatments, both psychological and pharmacological. Further studies are needed to confirm this hypothetical model, using more structured and reproducible assessment techniques.