The recurrent PPP1CB mutation p.Pro49Arg in an additional Noonan-like syndrome individual: Broadening the clinical phenotype

Abstract

We report on a 12-year-old Brazilian boy with the p.Pro49Arg mutation in PPP1CB, a novel gene associated with RASopathies. This is the fifth individual described, and the fourth presenting the same variant, suggesting a mutational hotspot. Phenotypically, he also showed the same hair pattern—sparse, thin, and with slow growing—, similar to the typical ectodermal finding observed in Noonan syndrome-like disorder with loose anagen hair. Additionally, he presented craniosynostosis, a rare clinical finding in RASopathies. This report gives further support that this novel RASopathy—PPP1CB-related Noonan syndrome with loose anagen hair—shares great similarity to Noonan syndrome-like disorder with loose anagen hair, and expands the phenotypic spectrum by adding the cranial vault abnormality. © 2017 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

TO THE EDITOR

In June, Gripp et al. [2016] described mutations in a novel gene (protein phosphatase one catalytic subunit beta—PPP1CB) in four unrelated individuals presenting clinical features similar to those found in Noonan syndrome-like disorder with loose anagen hair (NSLH—MIM#607721). This disorder is considered part of the RASopathies, a group of conditions that presents neuro-cardio-facio-cutaneous involvement, including, besides NSLH, Noonan syndrome (NS—MIM#163950), Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines (NSML—MIM#151100), cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (CFC—MIM#115150), and Costello syndrome (CS—MIM#218040). These disorders are caused by heterozygous germline mutations in genes of the RAS mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway that plays a role in cellular proliferation, differentiation and survival. The most prevalent disorder of the group is NS, which also shows the greatest genetic heterogeneity—mutations in more than ten different genes have been associated with NS [Aoki et al., 2016]. On the other hand, NSLH is caused, almost exclusively, by the missense mutation p.Ser2Gly in SHOC2, and is characterized by facial features similar to those observed in NS (mainly ocular hypertelorism, palpebral ptosis, dowslanting palpebral fissures, low-set posteriorly angulated ears, and overfolded superior pinna); short stature, frequently with proven growth hormone (GH) deficiency; cognitive deficits; relative macrocephaly, small posterior fossa resulting in Chiari I malformation; hypernasal voice; cardiac defects, especially dysplasia of the mitral valve and septal defects; and ectodermal abnormalities, in which the most characteristic feature is the hair anomaly, including easily pluckable, sparse, thin, slow growing hair [Cordeddu et al., 2009; Gripp et al., 2013]. The similar phenotype to NSLH, identified in the four unrelated individuals described by Gripp et al. [2016] with mutations in PPP1CB, component of the RAS/MAPK pathway, lead the authors to consider the condition a novel RASopathy and to propose the term PPP1CB-related Noonan syndrome with loose anagen hair (P-NS-LAH) for this novel disorder.

We report on a further individual harboring a recurrent mutation in PPP1CB, and showing, besides the typical features of a RASopathy, craniosynostosis.

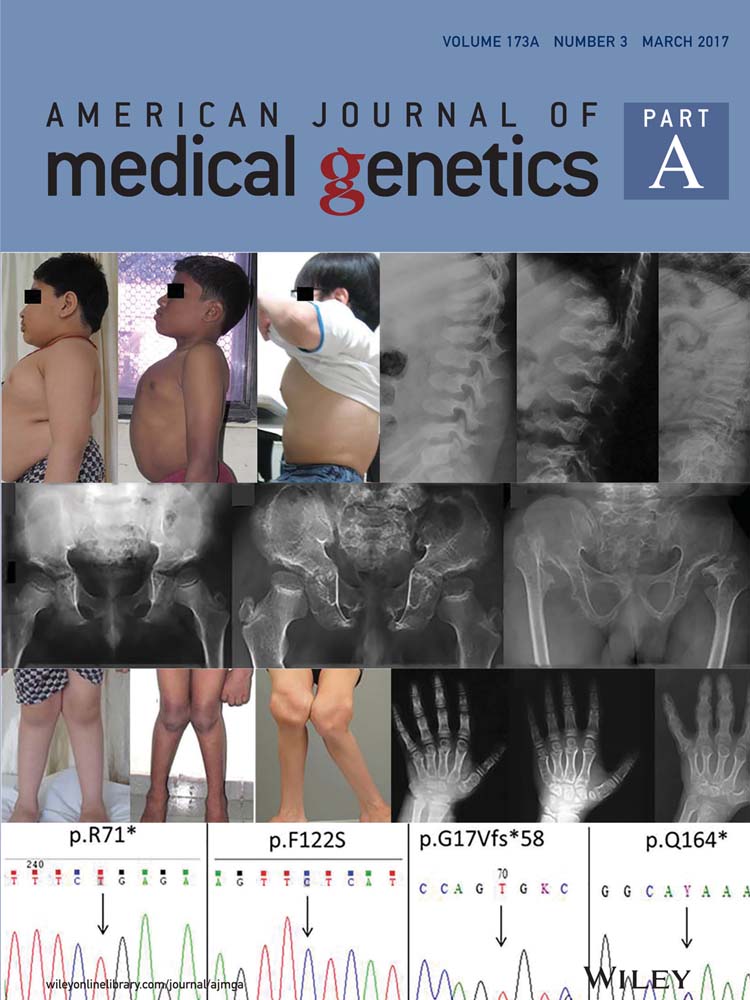

This patient was enrolled in an ongoing clinical and molecular study of individuals with RASopathies, approved by the local institutional review board (Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo—CAPpesq # 0843/08). The patient was included after written consent was obtained from one parent. The proband was a 12-year-old boy, the second child of a sibship of three, from non-consanguineous healthy parents. He was born at term (40 weeks), after an uneventful pregnancy, with a birth weight of 4,005 g, length of 52 cm, and occipital-frontal circumference (OFC) of 33 cm. In the neonatal period, a cardiac anomaly was suspected and the echocardiogram showed a patent foramen ovale. At age 12 months, his echocardiogram was normal. He developed distortion of the skull shape, and at age 3 months, a diagnosis of craniosynostosis was established, with precocious fusion of the sagittal and bilateral, partial coronal sutures. Cranioplasty was performed at age 1 year 9 months, with no major complications. Cryptorchidism was surgically corrected at 6 months. His hair always showed slow growth, without the need for haircut. Complementary exams disclosed: Abnormal echogenicity of the left renal sinus on abdominal ultrasound; normal EEG; and mild scoliosis on spine radiographs. Nephrology evaluation dismissed the kidney abnormality. The physical examination at age 3 years 11 months showed a weight of 14.4 kg (10–25th centile); height of 99 cm (10–25th centile), OFC of 52.5 cm (75th centile); thin and sparse hair; laterally sparse eyebrows; typical facial features of NS, with tall forehead, bitemporal narrowing, ocular hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures, posteriorly angulated ears, and deep philtrum; webbed neck; pectus carinatum superiorly and excavatum inferiorly (Fig. 1). He developed with normal motor milestones, but showed delay and difficulty in speech, with normal hearing. In school, at 5 years 6 months, the most recent time the patient was evaluated, he required additional support for fine motor skills. No microscopic analysis of the hair bulb was performed. This patient belongs to a cohort of 50 Brazilian probands negative for pathogenic variants in the known genes associated with Noonan syndrome analyzed by whole-exome sequencing in search for novel genes associated with RASopathies [Yamamoto et al., 2015]. Reanalysis of the 40 remaining individuals in whom no molecular basis was elucidated, disclosed, in the patient here reported, the hererozygous c.146C>G:p.Pro49Arg mutation in exon two of PPP1CB (NM_002709), a recurrent mutation described in three out of four individuals by Gripp et al. [2016] (Table I). No parental DNA was available for demonstrating a de novo event. In the remaining 39 negative probands with a RASopathy phenotype, there was none with a similar hair abnormality.

| Clinical features | Patient 1 Gripp et al. [2016] | Patient 2 Gripp et al. [2016] | Patient 3 Gripp et al. [2016] | Patient 4 Gripp et al. [2016] | Present patient | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | M | F | F | M | 3M/2F |

| Age of last evaluation or contact | 5 3/12 years | 9 years | 4 7/12 years | 21 years | 5 6/12 years | |

| Origin | USA | USA | USA/Philipines | USA | Brazil | |

| Prenatal | ||||||

| Polyhydramnios/fetal hydrops | – | – | Increased NTa | – | – | 1/5 |

| Neonatal | ||||||

| Gestational age (weeks) | Term | 34 (Placental abruption) | 35 | Term | 40 | Term 3/5 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3,520 (50thcentile) | 2,610 (75–90th centile) | 2,830 (75–90th centile) | 3,910 (75th centile) | 4,005 (>90th centile) | BW >75th centile 3/5 |

| Birth length (cm) | 52 (50–75th centile) | 47.6 (75th centile) | 46 (50th centile) | 53.4 (75–90th centile) | 52 (75–90th centile) | BL >75th centile 2/5 |

| Birth head circumfercence (cm) | NA | NA | NA | 38.1 (>97th centile) | 33 (2–50th centile) | BOFC >97th centile 1/2 |

| Feeding problems | + | + (Neonatal) | + (Neonatal) | – | – | 3/5 |

| Feeding tube/gastrostomy | + (9–20months) | + (neonatal) | + (Neonatal) | – | – | 3/5 |

| Growth | ||||||

| Failure to thrive | + | NA | NA | NA | – | 1/2 |

| Height (cm) | 97 (<2nd centile) | 114 (<2nd centile) | 3rd centile | 167 (50–75th centile) | 107.5 (10–25th centile) | |

| Short stature | + | + | + | – | – | 3/5 |

| GH treatment | + | NA | NA | NA | – | 1/2 |

| Craniofacial | ||||||

| Macrocephaly | + (Relative) | + (Relative) | + (Relative) | + | + (Relative) | 5/5 |

| Prominent forehead/dolicocephaly | + | + | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| Dowslanting palpebral fissures | + | Mild | – | – | Mild | 3/5 |

| Hypertelorism | + | Mild | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| Proptosis | + | – | – | – | – | 1/5 |

| Epicanthus | – | – | + | – | – | 1/5 |

| Low-set posteriorly rotated ears | + | + | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| Ophthalmologic abnormalities | Tear duct stenosis | Strabismus | – | Optic nerve hypoplasia, nystagmus, impaired vision | – | 3/5 |

| Hearing loss | – | Possible | Mild | – | – | 1/5 |

| Short/webbed neck | – | Short | – | – | Short and webbed | 2/5 |

| Cardiac | ||||||

| Structural anomaly | Mitral valve thickening | – | Valvar pulmonary stenosis | NA | Patent ductus arteriosus | 3/4 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | – | – | – | NA | – | 0/4 |

| Arrythmias | Right bundle branch block | – | NR | NA | – | 1/3 |

| Pectus deformity | – | Excavatum | – | – | Cariantum/excavatum | 2/5 |

| Cryptorchidism | + | – | + | 2/3 | ||

| Developmental delay | + | + | + | + | + | 5/5 |

| Walked unassisted (months) | 22 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 15 | |

| First words | NA | NA | 22 (Two-word sentences) | 24 (Two-word sentences) | 24 | |

| Therapy services in school | + | + | NA | + | + | 4/5 |

| Hypotonia | – | Mild | + | – | – | 2/5 |

| Seizures | NA | NA | NA | NA | Normal EEG | 0/1 |

| Behavior | Anxious | – | – | Very active, impulsive, anxious | – | 2/5 |

| Central nervous system abnormalities | ||||||

| Ventriculomegaly | Third and lateral ventricles (mild) | Borderline lateral ventricles | Third and lateral ventricles | Mild third and lateral ventricles; cystic fourth ventricle | – | 3/5 |

| Cerebellum | Chiari I | – | Cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (mild) | Dandy–Walker malformation | Normal cranial CT scan | 3/5 |

| Craniosynostosis | NA | NA | NA | NA | Sagittal, coronal | 1/1 |

| CNS surgical procedure | – | – | – | – | Cranioplasty (1y9m) | 1/1 |

| Ectodermal | ||||||

| Slow growing hair | + | – | + | + | + | 4/5 |

| Unruly hair texture | + | + | – | + | – | 3/5 |

| Curly hair | + | – | – | – | – | 1/5 |

| Pigmented lesions | Freckling | Café-au-lait spots | Hypopigmention on back | – | Nevi | 4/5 |

| Skeletal | ||||||

| Kyphosis/ scoliosis | NA | NA | NA | NA | Mild scoliosis | 1/1 |

| Tumors | ||||||

| Vascular anomalies | – | – | Hemangioma on lip, chin, and chest | – | – | 1/5 |

| Cancer | – | – | – | – | – | 0/5 |

| Other | Severe bGER, laryngomalacea, redundant arytenoid tissue, inguinal hernia | Perauricular pit (also in her father) | Left preauricular pit | |||

| PPP1CB mutation | p.Pro49Arg (de novo) | p.Ala56Pro (de novo) | p.Pro49Arg (de novo) | p.Pro49Arg (de novo) | p.Pro49Arg (NA) |

- NA, not available or not assessed.

- a NT, nuchal translucency.

- b GER, gastroesophageal reflux.

This is the fifth individual described to harbor a missense mutation in PPP1CB and the fourth to show the same p.Pro49Arg mutation [Gripp et al., 2016]. This patient has a different ethnicity from the previous described individuals, further supporting the idea that this is a mutational hotspot. As the number of patients with mutations in PPP1CB described to date is very small, the phenotype of this novel RASopathy is only emerging. In the neonatal and perinatal periods, no major findings were consistently observed: Increased nuchal translucency on fetal ultrasound and high birth weight (>90th centile) were observed in two instances each; feeding problems were reported in three individuals, only one requiring prolonged tube feeding. The two other infants were premature, and in one, difficulty in sucking and swallowing was partly attributed to a hemangioma (Table I). As a preliminary analysis, Gripp et al. [2016] highlighted the similarities of the individuals with PPP1CB mutations and those with SHOC2 mutation (NSLH), especially the hair pattern, with slow growth and abnormal texture. Our patient also showed slow growing hair with a thin texture, suggestive of loose anagen hair, although no evaluation of the root sheaths was performed. For now, the hair abnormality, similarly to that observed in NSLH, seems to be a prevalent characteristic among the individuals with PPP1CB mutations (Table I, Fig. 1). Other clinical manifestations observed in the majority (80%) of the five individuals harboring mutations in PPP1CB include: Relative or absolute macrocephaly, distinctive facial features (prominent forehead/dolicocephaly, ocular hypertelorism, low-set, posteriorly angulated ears); developmental delay (mean age of walking unassisted was 18 and 8/12 months, and two words sentences around 2 years of age), and learning/behavior problems, often requiring therapy services. The two hallmarks of the RASopathies in general, short stature and cardiac anomalies, were present in 3/5 (60%) and 3/4 (75%), respectively. Cardiac findings were restricted to structural defects, mainly pulmonary and mitral valve abnormalities. The latter is a common finding in NSLH [Cordeddu et al., 2009]. Other abnormalities shared by both conditions are observed in the central nervous system: 3/5 (60%) of the individuals harboring PPP1CB mutations presented with ventriculomegaly, Chiari I, and/or Dandy–Walker malformations [Cordeddu et al., 2009]. The cranial vault abnormality observed in our patient could be part of the phenotype caused by mutations in PPP1CB. Premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures (craniosynostosis) can be an isolated anomaly or part of a syndrome. Dysregulation of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) signaling cascade is a well-recognized cause of syndromic craniosynostosis [Twigg and Wilkie, 2015]. FGFR proteins are receptor tyrosine kinases upstream of the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway. Recently, Twigg et al. [2013] found a reduced dosage of ERF1/2, a binding target of the paralogous kinases ERK1 and ERK2, key effectors of the RAS/MAPK pathway, to be responsible for complex craniosynostosis in humans and mice. Although, these studies associate the involvement of the RAS/MAPK pathway in craniosynostosis, this feature is not a typical, common characteristic in RASopathies [Twigg and Wilkie, 2015]. Nevertheless, reports of NS individuals with this cranial vault abnormality, especially with mutations in KRAS, have been described. In a review of all NS individuals harboring KRAS mutations described in the literature, 6/62 showed craniosynostosis (10%), a figure greater than 300 times the prevalence in the general population [Addissie et al., 2015]. In addition, Takenouchi et al. [2014] described a 2 year 3 months-old boy presenting the typical heterozygous c.4A>G (p.Ser2Gly) mutation in SHOC2 and craniosynostosis involving the right coronal, sagittal, and bilateral lambdoid sutures. He showed clinical features of a RASopathy, such as fetal pleural effusion, fetal hydrops, failure to thrive, short stature, sparse hair, ocular hypertelorism, and atrial tachycardia. Thus, dysregulation of the RAS/MAPK pathway in different RASopathies caused by alterations in KRAS, SHOC2 and now, PPP1CB, may contribute to premature cranial suture fusion. Further, reports are required to delineate the complete phenotypic and genotypic spectrum of this novel RASopathy, including risk for cancer development, as germline mutations in RAS/MAPK pathway genes could increase the risk for malignant neoplasms [Kratz et al., 2015]. In these five individuals harboring PPP1CB mutations, although vascular proliferative lesion has been observed in one, no malignant tumor was reported.