Barber–Say syndrome and Ablepharon–Macrostomia syndrome: An overview

Abstract

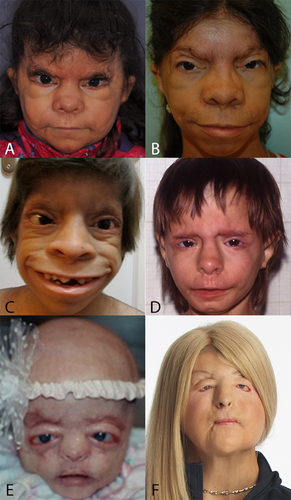

Barber–Say syndrome (BSS) and Ablepharon–Macrostomia syndrome (AMS) are congenital malformation syndromes caused by heterozygous mutations in TWIST2. Here we provide a critical review of all patients published with these syndromes. We excluded several earlier reports due to misdiagnosis or insufficient data for reliable confirmation of the diagnosis. There remain 16 reliably diagnosed individuals with BSS and 16 with AMS. Major facial characteristics present in both entities, albeit often in differing frequencies, are excessive facial creases, hypertelorism, underdevelopment of the anterior part of the eyelids (anterior lamella), ectropion, broad nasal ridge and tip, thick and flaring alae nasi, protruding maxilla, wide mouth, thin upper vermillion, and attached ear lobes. In BSS a remarkable extension of the columella on the philtrum can be seen, and in both the medial parts of the cheeks bulge towards the corners of the mouth (cheek pads). Scalp hair is sparse in AMS only, but sparse eyebrows and eyelashes occur in both entities, and general hypertrichosis occurs in BSS. We compare these characteristics with those in Setleis syndrome which can also be caused by TWIST2 mutations. The resemblance between the three syndromes is considerable, and likely differences seem larger than they actually are due to insufficiently complete evaluation for all characteristics of the three entities in the past. It is likely that with time it can be concluded that BSS. AMS and Setleis syndrome form a continuum. © 2016 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

In 1982, the pediatrician Nancy D. Barber and the pediatrician-clinical geneticist Burhan Say described a 3.5-year-old girl with a pattern of multiple congenital anomalies, characterized by “macrostomia, ectropion, atrophic skin, hypertrichosis, and growth retardation” of which they were unable to find an earlier description [Barber et al., 1982]. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up (N. Barber, personal communication, 2015). It has been suggested that possibly an earlier description can be found in Janssen and de Lange [1945] who labeled it as “familial congenital hypertrichosis totalis (trichostasis)” [de Knecht-van Eekelen and Hennekam, 1994]. David et al. [1991] presented a second patient, and Martinez Santana et al. [1993] a third patient. These latter authors named the entity Barber–Say syndrome (BSS), and suggested it to be an ectodermal dysplasia with autosomal recessive inheritance, because of the consanguinity of the parents of their patients. The occurrence in two generations suggested autosomal dominant inheritance [Dinulos and Pagon, 1999; Roche et al., 2010]. In total 19 patients have been published as having BSS [Barber et al., 1982; David et al., 1991; Martinez Santana et al., 1993; Sod et al., 1997; Mazzanti et al., 1998; Dinulos and Pagon, 1999; Cortés et al., 2000; Ng and Rajguru, 2006; Tenea and Jacyk, 2006; Haensel et al., 2009; Martins et al., 2010; Roche et al., 2010; Suga et al., 2014; Marchegiani et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2016].

In 1977 the neuro-pediatrician Gillian T. McCarthy and her assistant Carolyn West [McCarthy and West, 1977] described two patients with absent eyelids, large mouth, and multiple other anomalies that they named ablepharon–macrostomia syndrome (AMS). Since then, 19 patients were reported as having AMS [Hornblass and Reifler, 1985; Cesarino et al., 1988; Jackson et al., 1988; Markouizos et al., 1990; Price et al., 1991; Cruz et al., 1995; Pellegrino et al., 1996; Ferraz et al., 2000; Amor and Savarirayan, 2001; Stevens and Sargent, 2002; Brancati et al., 2004; Cavalcanti et al., 2007; Kallish et al., 2011; Rohena et al., 2011; Larumbe et al., 2011; Feinstein et al., 2015]. McCarthy and West [1988] suggested an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance due to the resemblance of the phenotype with other entities with eyelid abnormalities that followed this pattern of inheritance. Later on the occurrence of AMS in two generations was reported, indicating an autosomal dominant inheritance to be more likely [Ferraz et al., 2000; Rohena et al., 2011].

Gorlin et al. [1990] suggested BSS and AMS to be allelic entities due to the substantial phenotypic overlap. This was confirmed by an international collaborative study as it demonstrated that both disorders can be caused by heterozygous mutations in TWIST2 [Marchegiani et al., 2015]. TWIST2 is located at 2q37.3, encodes for a bHLH protein that binds to E-box DNA motifs as a heterodimer with other similar proteins, and is considered to act as a negative regulator of transcription. TWIST2 regulates mesenchymal stem cell differentiation and influences chondrogenic and dermal tissues. The authors suggested that TWIST2 mutations alter DNA-binding activity of TWIST2, and, thus, can have a dominant—negative and a gain-of-function effect [Marchegiani et al., 2015]. All 10 patients with AMS had the same E75K missense mutation in TWIST2, and the 11 patients with BSS had one of two missense mutations, both also involving codon 75 (E75Q and E75A), and 1 patient had a 6-bp duplication at codons 77 and 78. All these TWIST2 mutations are in the basic domain of the protein. All mutations affect sites that directly recognize and bind to E-box motifs of DNA.

TWIST2 mutations are also known to cause Setleis syndrome (focal facial dermal dysplasia 3), as homozygous nonsense mutations (Q119X; Q65X) have been reported in several patients [Tukel et al., 2010], later on confirmed by a homozygous 1 bp deletion (168delC) in another patient [Cervantes-Barragan et al., 2011] (please see further discussion under Differential Diagnosis).

The goal of the present manuscript is to critically review literature and to provide an overview of both BSS and AMS. We analyze resemblances and differences between the two entities, and discuss entities that should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Some major aspects of management are reviewed. In a separate paper we will discuss the consequences of having BSS and AMS for affected individuals and their families [De Maria et al., in preparation].

METHODS

We searched for potentially suitable publications in PubMed using as MeSH terms “Barber Say,” “Barber–Say,” “Barber Say syndrome,” “Barber–Say syndrome” and “ablepharon macrostomia,” “ablepharon–macrostomia,” and “ablepharon–macrosomia syndrome.” The reference lists of all thus acquired publications were hand-searched for further potentially suitable publications. We used no initial exclusion criteria. For some patients we contacted the authors to ask for further information if these were not available in the original publications. Dr Nancy Barber added additional information on the original patient (N. Barber, personal communication 2015). The patient described by Mazzanti et al. [1998] and the patients described by Roche et al. [2010] including the subsequently born second affected girl in this family were evaluated in person.

All descriptions and clinical photographs affected individuals were critically reviewed by two authors (B.DeM.; R.C.H.) in joint meetings. Descriptions in the text that differed clearly from the available clinical photographs were scored as visible on the photographs. If uncertainties remained the feature was not scored for the patient involved. Several patients were excluded as likely a different disorder was present [Pellegrino et al., 1996; Amor and Savarirayan, 2001; Cavalcanti et al., 2007; Kallish et al., 2011; Larumbe et al., 2011; Suga et al., 2014], or we remained uncertain about the diagnosis (please see Differential Diagnosis for a more detailed discussion of these reports) [Sod et al., 1977; Dinulos and Pagon, 1999 (patient 2); Ng and Rajguru, 2006].

RESULTS

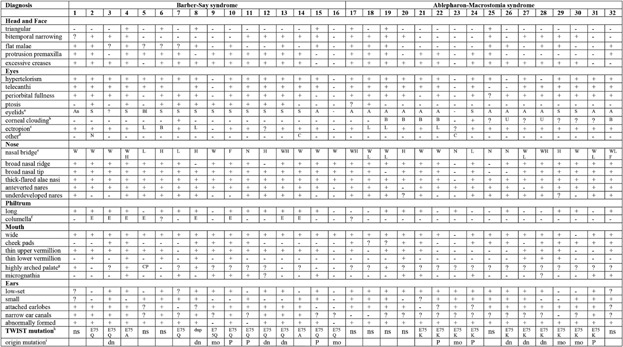

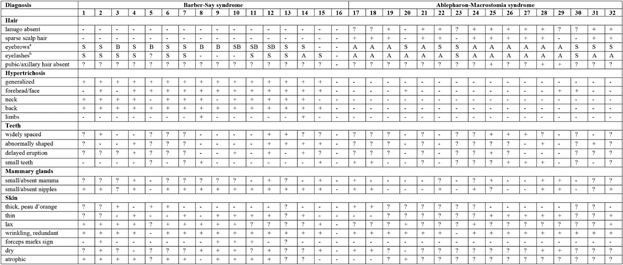

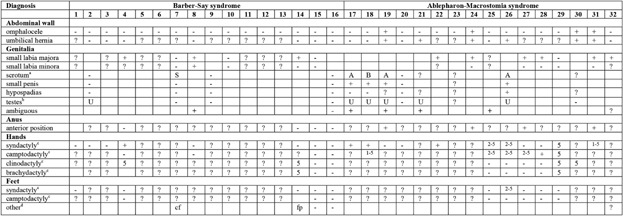

The phenotypes of all individuals with BSS and AMS are summarized in Table I for the general manifestations, in Table II for the ectodermal data, and Table III for the anomalies present in all other body parts. The phenotype is illustrated in Figures 1-9. In Table IV the data of the group of individuals with BSS and those with AMS are compared to an overview of manifestations in Setleis syndrome [Cervantes-Barragan et al., 2011; Giordano et al., 2014; personal observations R.C.H.].

- BSS: (1) Barber et al. [1982]; (2) David et al. [1991]; (3) Martinez Santana et al. [1993]; (4) Mazzanti et al. [1998]; (5) Dinulos (patient 1) [1999]; (6) Cortés et al. [2000]; (7) Tenea and Jacyk [2006]; (8) Haensel et al. [2009]; (9–10) Roche et al. [2010]; (11) Marchegiani et al. [2015]; (12) Martins et al. [2010]; (13–15) Marchegiani et al. [2015]; (16) Singh et al. [2016]. AMS: (17) McCarthy and West [1977]; (18) McCarthy and West [1977] and Jackson [1988]; (19) Hornblass and Reifler [1985]; (20) Cesarino et al. [1988]; (21) Price et al. [1991]; (22) Cruz et al. [1995]; (23–24) Ferraz et al. [2000]; (25–28) Stevens and Sargent [2002]; (29) Brancati et al. [2004]; (30–31) Rohena et al. [2011]; (32) Feinstein et al. [2015].

- aAn, ankyloblepharon; S, small; Bl, blepharophimosis; A, “ablepharon” (in fact underdevelopment of anterior lamella; see text).

- bU, unilateral; B, bilateral.

- cL, lower eyelid; B, both upper and lower eyelid.

- dN, nystagmus; C, coloboma.

- eW, wide; H, high; L, low; F, flat; N, normal.

- fE, extended.

- gCP, cleft palate.

- hns, non studied; dup, Q77_R78dup.

- idn, de novo; P, paternally inherited; mo, mosaic.

- BSS: (1) Barber et al. [1982]; (2)David et al. [1991]; (3) Martinez Santana et al. [1993]; (4) Mazzanti et al. [1998]; (5) Dinulos (patient 1) [1999]; (6) Cortés et al. [2000]; (7) Tenea and Jacyk [2006]; (8) Haensel et al. [2009]; (9–10)Roche et al. [2010]; (11) Marchegiani et al. [2015]; (12) Martins et al. [2010]; (13–15) Marchegiani et al. [2015]; (16) Singh et al. [2016]. AMS: (17) McCarthy and West [1977]; (18) McCarthy and West [1977] and Jackson [1988]; (19) Hornblass and Reifler [1985]; (20) Cesarino et al. [1988]; (21) Price et al. [1991]; (22) Cruz et al. [1995]; (23–24) Ferraz et al. [2000]; (25–28) Stevens and Sargent [2002]; (29) Brancati et al. [2004]; (30–31) Rohena et al. [2011]; (32) Feinstein et al. [2015].

- aS, parse; B, broad; A, absent.

- bS, sparse; A, absent.

- BSS: (1) Barber et al. [1982]; (2)David et al. [1991]; (3) Martinez Santana et al. [1993]; (4) Mazzanti et al. [1998]; (5) Dinulos (patient 1) [1999]; (6) Cortés et al. [2000]; (7) Tenea and Jacyk [2006]; (8) Haensel et al. [2009]; (9–10) Roche et al. [2010]; (11) Marchegiani et al. [2015]; (12) Martins et al. [2010]; (13–15) Marchegiani et al. [2015]; (16) Singh et al. [2016]. AMS: (17) McCarthy and West [1977]; (18) McCarthy and West [1977] and Jackson [1988]; (19) Hornblass and Reifler [1985]; (20) Cesarino et al. [1988]; (21) Price et al. [1991]; (22) Cruz et al. [1995]; (23–24) Ferraz et al. [2000]; (25–28) Stevens and Sargent [2002]; (29) Brancati et al. [2004]; (30–31) Rohena et al. [2011]; (32) Feinstein et al. [2015].

- aS, shawl; A, absent; B, bifid scrotum.

- bU, undescended testis.

- cNumbers indicate fingers/toes that are involved.

- dcf, club feet; fp, prominent fetal pads.

| Barber–Say syndrome (%)a | Ablepharon–Macrostomia syndrome (%)a | Setleis syndrome (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Face morphology | |||

| Bitemporal narrowing/atrophic skin | 50/25 | 56/– | 50–100/50–100 |

| Excessive creases | 81 | 81 | 10–50d |

| Hypertelorism | 88 | 81 | ? |

| Small/absent eyelids | 69/6 | 19/75 | 10–50 |

| Corneal clouding | 6 | 50 | ? |

| Ectropion | 81 | 94 | ? |

| Entropion | — | 6 | 10–50 |

| Broad nasal ridge and tip | 88 | 75 | 50–100 |

| Thick-flared alae nasi | 100 | 88 | 10–50 |

| Extension septum on philtrum | 50 | — | 50–100 |

| Protruding premaxilla | 75 | 50 | 10–50 |

| Wide mouth | 100 | 81 | 1–10 |

| Cheek pads | 38 | 69 | 1–10 |

| Thin upper vermillion | 88 | 50 | — |

| Everted upper vermillion | — | — | 50–100 |

| Small ears | 50 | 75 | 1–10 |

| Attached earlobes | 69 | 75 | 10–50 |

| Narrow ear canals | 63 | 6 | ? |

| Ectodermal signs | |||

| Sparse scalp hair | — | 75 | 10–50 |

| Eyebrows sparse or absent | 63b | 100c | 50–100e |

| Eyelashes sparse or absent | 69b | 100c | 50–100f |

| Hypertrichosis general | 94 | — | — |

| Hypertrichosis forehead/face | 81 | 19 | 50–100 |

| Abnormally shaped teeth | 31 | 13 | ? |

| Mamma small or absent | 19 | 25 | ? |

| Nipples small or absent | 81 | 44 | ?g |

| Skin thin | 44 | 38 | 10–50d |

| Skin wrinkled, redundant | 88 | 94 | 50–100 |

| Genitalia | |||

| Small labia majora or scrotum | 13 | 56 | 10–50h |

| Small or ambiguous genitalia | 6 | 38 | — |

| Limbs | |||

| Syndactyly fingers | 6 | 44 | — |

| Camptodactyly fingers | — | 38 | — |

| Underdeveloped thenar/hypothenar | — | — | 10–50 |

- a The total number of patient used was 16 for BSS, 16 for AMS, and 24 for Setleis syndrome [Cervantes-Barragan et al., 2011; Giordano et al., 2014; personal observations RCH]. For BSS and AMS the percentages were referred only to positively scored features as indicated in Tables I–III.

- b Mainly sparse.

- c Mainly absent.

- d Mainly eyelids.

- e Frequently medial one third runs up laterally.

- f Frequently also mal-positioned including distichiasis.

- g Supernumerary nipples 10–50%.

- h Indicates genitourinary anomalies (no separate data on genitalia available).

DISCUSSION

In evaluating the clinical data provided in Tables I–III, we realize that only signs and symptoms described in literature and/or visible in pictures could be scored, and if a sign or symptom was not mentioned it does not necessarily indicate it was not present. As a consequence all figures should be considered as minimal figures as actual figures may be higher. We provide a summary of the major characteristics of both syndromes in Table IV. These characteristics are described below, stressing especially similarities and differences between the syndromes, and mentioning additional infrequent characteristics.

Face

The general head shape in BSS and AMS are normal. Dolichocephaly was present at birth in three patients [McCarthy and West, 1977; Cesarino et al., 1988; Mazzanti et al., 1998] but the shape of the head became normal with time. Bitemporal narrowing and flat malae are present in both syndromes, protrusion of the maxilla (Fig. 5) occurs in three-quarters of all BSS patients, and becomes frequently more pronounced after infancy. There are excessive skin creases, both between eyebrows and running laterally to nose and mouth, in both entities. The somewhat older appearance compared to calendar age will in part be due to this (Fig. 1).

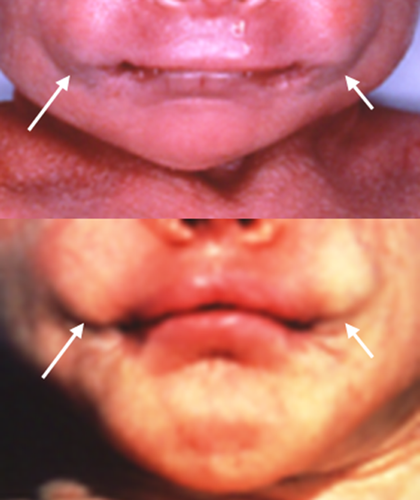

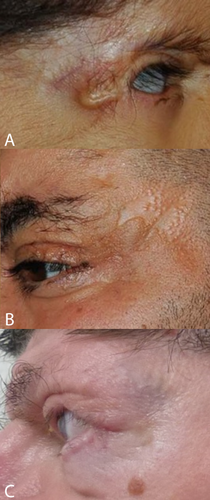

The main peri-ocular signs include peri-orbital fullness, hypertelorism, telecanthi, and “underdevelopment of eyelids,” typically mainly the lower one. If studied in more detail not the total eyelids are underdeveloped, but only the anterior parts (anterior lamella), which allows the medial and posterior lamella to protrude as in ectropion (Fig. 2) [Cruz et al., 1995]. In this respect, the eyelid abnormalities are limited to the skin part of the eyelids, and may be compared to forceps marks sign which can be present in Setleis syndrome. The term ablepharon is therefore in fact a misnomer, but for historical reasons we suggest to keep the term AMS unchanged. The anterior parts of the eyelids vary in their underdevelopment from being extremely small in AMS to minor reduction in size in BSS, to even less marked expression in a coloboma in a mosaic patient [Ferraz et al., 2000] and absence of eyelashes only of the medially lower lid [Marchegiani et al., 2015]. The underdeveloped anterior lamella causes ectropion, causing in turn lagophtalmus, which may need surgical correction [McCarthy and West, 1977; David et al., 1991; Price et al., 1991; Cruz et al., 1995; Ferraz et al., 2000; Stevens and Sargent, 2002; Brancati et al., 2004; Martins et al., 2010; Roche et al., 2010; Rohena et al., 2011; Feinstein et al., 2015; Marchegiani et al., 2015]. The continuous exposure may cause corneal clouding occurring in half of the patients with AMS. The cloudy cornea seem to become less marked after surgery [Jackson et al., 1988; Cruz et al., 2000; Stevens and Sargent, 2002; Brancati et al., 2004; Feinstein et al., 2015]. Visual impairments have been reported in almost one-third of patients. Photophobia may occur [Brancati et al., 2004; Rohena et al., 2011; Feinstein et al., 2015; Marchegiani et al., 2015]. A single AMS patient was found to have entropion [Stevens and Sargent, 2002]. Strabismus was also present in three BSS patients [Barber et al., 1982; David et al., 1991; Roche et al., 2010] and three AMS patients [McCarthy and West, 1977; Hornblass and Reifler, 1985; Jackson et al., 1988], and nystagmus was reported in BSS [David et al., 1991] and AMS as well [Hornblass and Reifler, 1985; Cruz et al., 1995].

The nasal bridge can be high, normal or flat, and is more frequently wide in AMS compared to BSS. In both entities distinctive signs are the broad ridge and tip, thick and flared alae nasi and small, anteverted nares. The columella can be broad [Barber et al., 1982; Mazzanti et al., 1998; Rohena et al., 2011], and may show a remarkable extension onto the philtrum. The philtrum itself is typically long. A striking feature is the unusually wide mouth occurring in almost all patients of both syndromes (Fig. 3). The cheeks protrude typically lateral of the corners of the mouth leading to a trait we indicate as cheek pads (Fig. 4), which is more frequent in AMS than in BSS. The upper vermillion is much more often thin in BSS patients compared to AMS patients, the lower vermilion is much less frequently thin in both entities. Cleft palate is only present in one patient [Dinulos and Pagon, 1999]. Thick gums have been present in four BSS patients [David et al., 1991; Martins et al., 2010; Marchegiani et al., 2015].

A small chin is present in more than one-third of patients in both syndromes, prognatia can occur in BSS [David et al., 1991; Dinulos and Pagon, 1999; Cortés et al., 2000], and also retrognatia has been described (Fig. 5) [Cesarino et al., 1988; Mazzanti et al., 1998]. The ears are typically low-set, small and mildly abnormally formed, with attached earlobes. These ear signs are more evident in AMS patients. Narrow ear canals have been reported far more frequently in BSS patients. Sometimes ears protrude in BSS [Dinulos and Pagon, 1999; Haensel et al., 2009; Marchegiani et al., 2015]. Impaired hearing has been reported several times, especially in AMS [Dinulos and Pagon, 1999; Stevens and Sargent, 2002; Brancati et al., 2004; Haensel et al., 2009; Martins et al., 2010].

Ectodermally Derived Structures

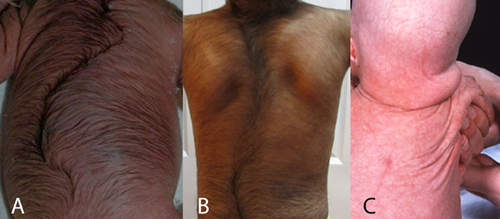

Hair

A major difference between BSS and AMS is the generalized hypertrichosis in BSS while in AMS hypertrichosis is uncommon, and, if it occurs, it is confined to the face. Absence of lanugo at birth and sparse scalp hair characterize AMS but were not reported in BSS (Fig. 6). Eyebrows and eyelashes are sparse in BSS but in AMS they typically are absent. Occasionally eyebrows are broad in BSS [Martinez Santana et al., 1993; Dinulos and Pagon, 1999; Haensel et al., 2009; Martins et al., 2010; Roche et al., 2010; Marchegiani et al., 2015]. In BSS eyelashes that were medially sparse and laterally bushy have been reported [Martinez Santana et al., 1993] and also a double row of eyelashes on the upper eyelid [Marchegiani et al., 2015]. Both are signs known to occur in Setleis syndrome. Three adult AMS patients were reported not to have pubic and axillary hair.

Lacrimal system

Alacrimia was present in two AMS patients [Cesarino et al., 1988; Rohena et al., 2011] and lacrimal duct stenosis in two BSS patients [Mazzanti et al., 1998; Marchegiani et al., 2015]. Abnormal positioning of the lacrimal punctum causing epiphora has been reported [Jackson et al., 1988].

Teeth

The teeth are generally widely spaced, small, and delayed in eruption in both entities. Sometimes missing teeth [Mazzanti et al., 1998], abnormally shaped teeth [Mazzanti et al., 1998; Martins et al., 2010; Marchegiani et al., 2015], natal teeth [Cesarino et al., 1988], and taurodontism [Martins et al., 2010] were reported. Malocclusion with an open bite occurs [David et al., 1991; Mazzanti et al., 1998; Martins et al., 2010; Rohena et al., 2011].

Skin

Skin is typically redundant, wrinkling, thin, and dry. In BSS more patients are reported to have a hyperlax and atrophic skin. In one family [Roche et al., 2010; Marchegiani et al., 2015] and in another affected individual [David et al., 1991] thinning of the skin resembling scarring was present bitemporally, and, thus, resembling the forceps marks sign in Setleis syndrome (Fig. 8). Two mosaic patients [Brancati et al., 2004; Rohena et al., 2011] show skin hyperpigmentations following Blaschko lines. Skin biopsies were performed in six BSS and three AMS patients. In some no abnormalities were found [Price et al., 1991; Mazzanti et al., 1998; Roche et al., 2010], others showed a decreased number of elastic fibers [Barber et al., 1982; Cesarino et al., 1988; David et al., 1991; Brancati et al., 2004; Tenea and Jacyk, 2006], or hair follicles and sebaceous glands attached to the subcutaneous tissue, an atrophic epidermis with hyperkeratosis and a thin reticular layer of the dermis [Martinez Santana et al., 1993].

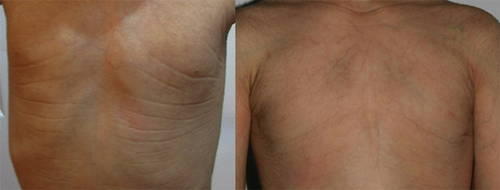

Mammae

Small or absent nipples are very frequent in both syndromes, both in females and males. Small or absent mammary glands have been reported in seven adult female patients (Fig. 9). Several younger females had a remarkable amount of fat tissue on the upper trunk.

Nails

In most BSS and AMS patients nails are described as being normal. Exceptions are small toe nails reported both in BSS [Mazzanti et al., 1998] and in AMS [Stevens and Sargent, 2002].

Sweat glands

The functioning of sweat glands was mentioned in only a single patient with AMS as being normal [Cesarino et al., 1988]. A skin biopsy in the original BSS patient showed sweat gland ectasia [Barber et al., 1982].

Genitalia

Abnormalities of the genitalia form part of both entities, but more frequently in AMS compared to BSS. Labia majora and scrotum are typically underdeveloped. Other signs are a small penis, hypospadias and undescended testes in males and small labia minora in females.

One female had hypospadias as well (opening of urethra in the upper vaginal wall) [Stevens and Sargent, 2002]. Genitalia have been described several times as ambiguous, but unfortunately details were not provided. Abnormally low position of the penis was reported twice [McCarthy and West, 1977; Cruz et al., 1995]. Whether this is the same as an anteriorly positioned anus that has been reported several times as well, is uncertain.

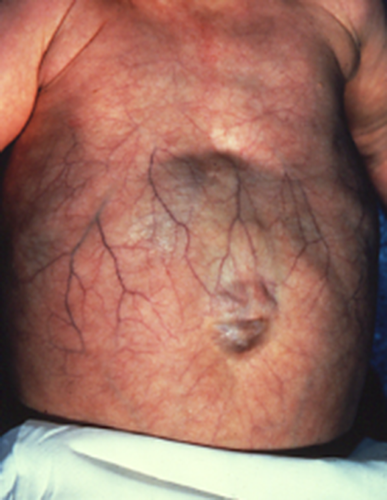

Other Characteristics

Visceral anomalies are infrequent. A single patient had mild right ventricular dilatation [Rohena et al., 2011] and another one a patent foramen ovale at birth [Feinstein et al., 2015]. The anterior abdominal wall is more frequently showing either an omphalocele or umbilical hernia in AMS (Fig. 7), and the umbilicus has also been described as unusually flat and up-ward pointing in AMS [McCarthy and West, 1977] or large [Stevens and Sargent, 2002]. In the limbs partial syndactyly of fingers occur in both entities, and camptodactyly almost exclusively in AMS. Other unusual manifestations have been laryngomalacia and tracheomalacia [David et al., 1991; Rohena et al., 2011], and a lipoma overlying the metopic suture [Stevens and Sargent, 2002].

Physical growth was reported to be normal in all patients except two who showed a decreased growth in height [Barber et al., 1982; Cesarino et al., 1988]. Cognition was normal in most patients but six showed delay [McCarthy and West, 1977; Barber et al., 1982; Hornblass and Reifler, 1985; Cesarino et al., 1988; Haensel et al., 2009; Marchegiani et al., 2015]. Whether the disturbed growth and development should be ascribed to the disorder or to other factors remains uncertain.

Differential Diagnosis

In the present study we did not include all patients published as having BSS and AMS. The patient reported by Ng and Rajguru [2006] was excluded only because the available information was too limited to be sure about the diagnosis. The authors did show a detail of the face showing the eyebrow, which had a shape unusual for BBS and would fit better Fraser syndrome, putting doubt about the diagnosis. We remained also in doubt about the patient reported by Sod et al. [1997] as the patient had no eye phenotype and there was not truly a wide mouth. It may be this patient has an unusually mild phenotype but without molecular confirmation it seems prudent to keep him separate for the time being.

Dinulos and Pagon [1999] published two cases hypothesizing a mother to son transmission of the disorder. The description and pictures of patient 1 are fitting well the diagnosis BSS but data on the child were insufficient to allow for a diagnosis and follow-up has proven to be impossible (personal communication 2015, Dr Marybeth Dinulos and Dr Darci Sternen). Because of this uncertainty we decided not to include this patient in the present overview.

The patient reported by Suga et al. [2014] showed a phenotype differing from BSS both in eye, face and body phenotype despite some overlap with BSS. At follow-up these differences have increased, and signs distinctive of BSS were noticed which; however, did not allow a clinical diagnosis up to now (personal communication 2015, Dr Kenichi Suga). Molecular analysis of TWIST2 failed to show a mutation. We concur with Dr Suga the patient must have another, as yet undiagnosed, entity.

Pellegrino et al. [1996] described a patient who had a complex rearrangement of 18q that caused at least a deletion of terminal 18q. This chromosome imbalance, the less marked eye signs, the presence of supernumerary nipples, cutis laxa, widely spread joint contractures, edema, and marked developmental delay and seizures make it unlikely that this patient should be diagnosed as having AMS. We remained uncertain about the patient reported by Amor and Savarirayan [2011] as the underdevelopment of the eyelids was less expressed, there was no hypertelorism, signs of the nose, mouth, and ears were much less clear compared to other patients, while the patient did have a significant developmental delay, seizures and cerebral anomalies at neuroradiology. The short palpebral fissures, laterally sparse eyebrows, entropion, everted lower lip, and large ears might in fact fit better a diagnosis of Setleis syndrome. The patient reported by Kallish et al. [2011] showed the phenotype of an acrofacial dysostosis, possibly Nager syndrome, and the differences to AMS were too significant to allow inclusion. The latter two patients [Amor and Savarirayan, 2011; Kallish et al., 2011] tested negatively for TWIST2 mutations [Marchegiani et al., 2015]. Lastly, the patient reported by Larumbe et al. [2011] clearly had severe congenital ichthyosis. One patient showing an overlap between Fraser syndrome and AMS was subsequently found to harbor a homozygous splice site mutation in FRAS1, confirming the diagnosis of Fraser syndrome [Cavalcanti et al., 2007; Schanze et al., 2013]. Fraser syndrome differs to BSS and AMS in the presence of cryptophthalmos, urinary tract defects, airway anomalies, and marked cutaneous syndactyly [Van Haelst et al., 2007].

The most important entity to differentiate from BSS and AMS is Setleis syndrome, which can also be caused by a TWIST2 mutation (Table IV). Setleis syndrome shows bitemporal narrowing with localized skin atrophy (forceps marks sign). Bitemporal narrowing is common in BSS and AMS too, and forceps marks sign has been described in three BSS patients. A further resemblance are the excessive skin creases although in Setleis syndrome these are predominantly present in the peri-orbital region. Eyelids can be markedly similar in the three entities, with the exception of entropion which is characteristic of Setleis syndrome. The broadness of the nose does not allow a firm differentiation between the three disorders, but the mouth differs: in Setleis syndrome there is a prominent and everted upper vermilion which is absent in AMS and BSS. In all three the mouth can be wide, but the cheek pads are infrequent in Setleis syndrome. The ectodermally derived structures in Setleis syndrome patients can be somewhat similar but typically these are less marked compared to BSS and AMS, and mamma anomalies have not been described. Also genital anomalies are less frequent and less marked, and the limb anomalies are mainly confined to underdevelopment of thenar and hypothenar in Setleis syndrome. We conclude the overlap between the three entities is significant but differentiation will in general be possible. We may expect that further patients will be described that show further overlap between the three syndromes, and we might need to conclude with time that BSS, AMS, and Setleis syndrome form in fact a spectrum of anomalies. The three patients reported with a phenotype resembling Setleis syndrome and in whom a duplication of the chromosome region 1p36.22p36.21 was found [Weaver et al., 2015], may be helpful in dissecting the mechanism(s) and gene(s) involved to explain the phenotype both in these patients as in patients with Setleis syndrome caused by TWIST2 mutations.

Verloes and Lesenfants [1977] described a single patient with macroblepharon, ectropion, hypertelorism, macrostomia syndrome (MEHM). A second case was reported by Corona-Rivera et al. [2013]. Both patients show facial characteristics remarkably similar to those in BSS and AMS consisting of hypertelorism, ectropion, corneal exposure, coloboma, broad nasal bridge, ridge and tip, anteverted nares, long and smooth philtrum, a thin upper vermilion, wide mouth, small mandible and zygomatic bones, and small ears. Visceral and limb anomalies are absent and growth and cognition are normal. Abnormalities of ectodermally derived structures are minimal (thick eyebrows, densely implanted eyelashes) or absent. It remains well possible that MEHM is allelic to BSS and AMS. Indeed a search for TWIST2 mutations has been initiated (personal communication 2015, Dr Alain Verloes).

Management

The face plays a central role in identity, attractiveness, and social interactions between humans. Of all physical handicaps, none is more devastating than facial disfigurement. It can severely affect social interactions and one's perception of self-image [De Sousa, 2008]. Patients with AMS and BSS will survive and most of them will have normal psychomotor development, but their aesthetic and social impairment, due to the craniofacial anomalies, will sometimes be very debilitating. Other manifestations, especially hypertrichosis, and underdeveloped mammae in females, may form another burden.

The eyelid anomalies in BSS and especially AMS can be very prominent, cause ectropion, and may result in corneal exposure with potential loss of vision. In severe ectropion with corneal exposure, surgical correction with skin grafts or local flaps with or without tarsorraphy is highly recommended. One may expect this to have excellent results as only the anterior lamella are abnormal but all other structures are normally formed. Indeed, in all reported surgical cases, this resulted in tremendous improvement of both aesthetics and functioning of the eyelids [McCarthy and West, 1977; David et al., 1991; Price et al., 1991; Cruz et al., 1995; Dinulos and Pagon, 1999; Stevens and Sargent, 2002; Brancati et al., 2004; Haensel et al., 2009; Martins et al., 2010; Rohena et al., 2011; Marchegiani et al., 2015]. In one patient amniotic membrane grafting was used [Feinstein et al., 2015].

For the other facial signs, it can be difficult to balance between on one hand timing of radical surgeries with best results in adolescence or early adulthood, leaving the growing face undisturbed as much as possible, and on the other hand the demands of the patients and their family, as they may insist on early surgical correction to look as normal as possible at a young age. Extensive surgery may have disastrous effects on craniofacial growth, resulting in a worse outcome on the long-term. A multidisciplinary approach by a team experienced in craniofacial anomalies, and an individualized treatment plan are essential for timing and optimizing functional and aesthetic outcome. Only case reports, often with limited information on exact surgical procedures to obtain a more natural facial appearance and no long-term follow up are published on individuals with AMC and BSS, so it remains hard to give clear guidelines for these problems. Reported surgical procedures include local flaps, face-lift procedures, forehead lifting, botox injections, fat grafting, orthognathic surgery, and nasal reconstruction with rib cartilage grafts [Mc Carthy and West, 1977; Mazzanti et al., 1998; Dinulos and Pagon, 1999; Stevens and Sargent, 2002; Brancati et al., 2004; Martins et al., 2010; Roche et al., 2010; personal observations N.R.]. In our opinion, such major procedures are best deferred until craniofacial growth is completed.

Hypertrichosis in BSS can be treated with laser therapy with good results, especially in patients with dark hair [Stevens and Sargent, 2002; Brancati et al., 2004; personal observations, unpublished]. The disadvantages are that multiple sessions are needed due to the growth cycles of hairs and that general anesthesia is needed in children as laser therapy can be very painful. Cosmetic mamma reconstructions using prostheses have been performed with good results [Stevens and Sargent, 2002; Brancati et al., 2004; personal observations N.R.].

No specific psychological help strategies have been described. The psycho-social impact of BSS and AMS can be marked due to the normal cognition but obviously different face and body appearance in both entities. No quality-of-life studies have been performed. It seems likely that full acceptance by their family and social context, offering access to plastic surgery without medicalization of the disorders, and providing psychological support from early age on to the patients, their parents and their sibs, will be major prerequisites for acceptance of the patients of the physical appearance and a high quality of life.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that there are several individuals published as having BSS or AMS but in whom in retrospect the diagnosis can be questioned or even rejected. When comparing the 16 BSS and 16 AMS patients in whom the diagnosis is highly likely, and frequently also molecularly confirmed, it is clear the overlap between the two entities is marked, and discrimination is mainly by differences in frequency of signs and symptoms that can occur in both entities. We expect that these differences may in reality even be smaller due to incomplete evaluation of patients for all manifestations of both entities. Main differences are the presence of general hypertrichosis, extension of the columella on the philtrum, narrow ear canals in BSS, and sparse scalp hair, more marked eyelid defects leading to more frequent cloudy cornea, and more marked distal limb anomalies in AMS. There are similar differences with Setleis syndrome. We expect that with time we can conclude that BSS, AMS and Setleis syndrome form in fact a spectrum but at the present time bibliographic proof for this is lacking.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are pleased to thank especially all patients and families for their participation in this study. We also thank all the physicians and other caregivers for their valuable help in gathering more data: N. Barber, O. Bartsch, F. Brancati, B. Chung, J. Corona-Rivera, M. Dinulos, M. Gallottini, B. Isidor, G. Izbizky, A. Kariminejad, S. Marchegiani, F. Martins, J. Ng, A. Singh, D. Sternen, C. Stevens, K. Suga, R. Tavakoli, A. Verloes, and M. Zenker.