First clinical report of an infant with microcephaly and CASC5 mutations

TO THE EDITOR

Congenital microcephaly, an occipital-frontal circumference of equal to or less than 2–3 standard deviations (SD) below the age-related population mean, denotes a fundamental impairment of brain development, and neurogenesis [Genin et al., 2012; Alcantara and O'Driscoll, 2014]. Primary autosomal recessive microcephaly (MCPH) is a heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder of prenatal onset that results in an OFC at birth at least 2–3 SD below the mean for sex, age, and ethnicity [Morris-Rosendahl and Kaindl, 2015]. By definition, patients with MCPH have intellectual impairment that is not the result of progressive cognitive decline, tend to be of normal height, weight, and appearance, and have normal chromosome analysis and brain scan results [Mahmood et al., 2011; Woods and Parker, 2013; Faheem et al., 2015]. Of the current 13 MCPH loci implicated in MCPH, variants that affect function in ASPM (MCPH5) account for 25–50% of cases [Mahmood et al., 2011; Morris-Rosendahl and Kaindl, 2015]. While other genes implicated in MCPH are less commonly affected in patients with primary microcephaly, they share similar functional properties. Indeed, the known MCPH genes encode proteins that are almost universally involved in the biology of centrioles and play part of cell cycle dynamics [Alcantara and O'Driscoll, 2014; Barbelanne and Tsang, 2014; Morris-Rosendahl and Kaindl, 2015]. CASC5, the gene responsible for MCPH4 [MIM 604321], codifies for a kinetochore scaffold protein required for the proper attachment of chromatin to the mitotic apparatus [Barbelanne and Tsang, 2014]. We report an infant with compound heterozygous variants in CASC5. To our knowledge, this is the first description of an infant with variants in CASC5 and the first report in an outbred patient.

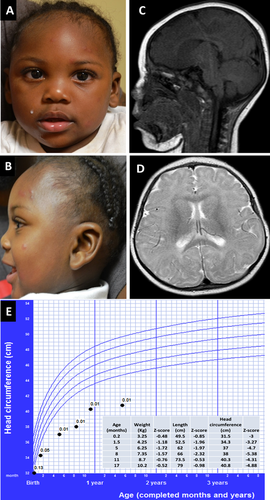

The African American male proband was born at term to a 23-year-old G2P2 mother. Birth weight was 3.080 kg (83 percentile), length was 49.5 cm (42 percentile), and OFC was 31.1 cm (<1 percentile; Z score −2.65). The family history was noncontributory, and there were no prenatal toxic exposures. No other birth defects or major dysmorphic features were identified postnatally. While his length and weight measurements fluctuated between low-for-age and normal during the first year of life, his OFC was consistently below −3 SD for age (Fig. 1). Medically he has remained healthy and at his current age of 17 months, he continues to be non-dysmorphic and with preserved weight and length, but with severe microcephaly (40.8 cm, −4.88). He has been able to achieve developmental milestones at normal ages. Magnetic resonance imaging performed at 7 months showed simplified gyral pattern, and a very mild delay of myelination (Fig. 1). A SNP microarray analysis was performed using a Cytoscan HD whole genome SNP array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara CA) with no abnormalities detected. From isolated DNA, a customized next generation sequencing panel for microcephaly including sequencing, and deletion/duplication analysis of 38 genes was performed (Supplementary Table SI). There were no deletions or duplications detected. However, the patient had compound heterozygous variants in the CASC5 (NM_170589.4) gene confirmed with Sanger sequencing. These two variants were submitted to ClinVar at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ (ClinVar accession numbers: SCV000256234.1 and SCV000256235.1) (Fig. 2). The de novo c.5262dupT (p.(I1755Yfs*2) variant was not reported in HGMD or another public database (dbSNP, ClinVar, Exome Variant Server, and Exome Aggregation Consortium). Meanwhile, the maternally inherited missense variant c.6560A>G (p. (D2178G)) was predicted to be damaging by SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/), MutationTaster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), Polyphen-2 (0.999, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), and Provean (−3.624, http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php). The physiochemical difference between Aspartic acid and Glycine is moderate (Grantham score = 94) and amino acid analysis conservation by Alamut (http://www.interactive-biosoftware.com/) indicates that the wild-type amino acid is moderately conserved. The c.6560A>G variant is very rare in the general population but particularly found in patients of African ancestry. The variant has a reported heterozygous minor allele frequency of 0.0034 (33/9694 alleles) in the Exome Aggregation Consortium and 0.0022 (8/3660) in the Exome Variant Server for people of this ancestry. Paternity was confirmed using 21 short tandem repeats (STR) markers with higher power of discrimination in the fragment analysis and by comparison of the allele size of STR markers in the patient and the parents.

While the etiology of microcephaly is largely heterogeneous, to date, the majority of the genetic defects identified in congenital microcephaly involve genes encoding proteins that play fundamental roles in various processes enabling cells to execute precise chromosomal segregation and mitotic division [Alcantara and O'Driscoll, 2014]. For the individual here described, careful review of the patient's medical history and maternal prenatal history failed to reveal potential environmental contributing factors. In the absence of other suggestive dysmorphic features, birth defects, vision/hearing impairments or a positive family history for microcephaly, and with the disproportionate microcephaly in relationship to weight and height, a brain MRI was obtained as it has been previously suggested [Ashwal et al., 2009]. Once chromosomal abnormalities were excluded, the possibility of MCPH was evaluated with a next generation sequencing panel and identified compound heterozygous variants in CASC5.

In the initial report that linked CASC5 to MCPH4, a single homozygous variant (p.Met2041Ile) thought to result in skipping of exon 18, was documented in three separate consanguineous Moroccan families with severe microcephaly [Genin et al., 2012]. Subsequently, the same variant was identified in four Algerian siblings who had moderate short stature, moderate to severe cognitive deficits, facial dysmorphism, and OFC ranging between −3 to −4 SD [Saadi et al., 2016]. The role of CASC5 in the genesis of microcephaly was further reaffirmed recently with the identification of a novel homozygous variant (c.6673-19T>A) in a consanguineous Pakistani family with severe microcephaly (−13 to −17 SD) and moderate to severe cognitive impairment [Szczepanski et al., 2016]. In addition to the expected resulting perturbation of the kinetochore function, the authors showed a severe impact on DNA damage response in the cells derived from affected individuals [Szczepanski et al., 2016].

Both previously reported pathogenic variants are splicing mutations and result in exon skipping. In the case here described, the previously unreported de novo frameshift variant is predicted to result in a premature truncation of the CASC5 protein. For the second variant, we interpret the c.6560A>G variant as unknown significance, but likely pathogenic, based on the low frequency in population databases, the trans configuration with the pathogenic c.5262dupT variant, the computational evidence support of pathogenicity, and the matching phenotype. Furthermore, the C.6560A>G variant is located in an area necessary for kinetochore localization and for interaction with NSL1 and DSN1 of the kinetochore network. The potential functional impact of this and other missense variants remains to be elucidated.

In summary, we presented the first detailed description of the anthropometric measurements during infancy for a patient with microcephaly related to CASC5. In agreement with many of the described cases, earlier developmental milestones have been preserved while no additional major malformations have been documented [Jamieson et al., 1999; Genin et al., 2012]. Given the limited number of patients reported with CASC5 pathogenic variants, this gene is expected to be a very rare cause of MCPH. This case illustrates, however, that alterations in this gene can be identified in outbred populations.