9p13.1p13.3 interstitial deletion: A case report and further delineation of a rare condition

TO THE EDITOR

The 9p deletion syndrome has been well characterized in the medical literature [Huret et al., 1988; Swinkels et al., 2008]. The majority involve a terminal deletion, with the breakpoint at 9p21 or more distal. Currently, only four case reports have been published on children with interstitial deletions that include 9p13 [Giltay et al., 1994; Eshel et al., 2002; Niemi et al., 2012]. The cases reported by Giltay et al. [1994] and Eshel et al. [2002] were identified on routine karyotype, and the deletion included band 9p12, which are larger interstitial deletions compared to our case. Niemi et al. [2012] reported two children with interstitial deletions occurring at 9p13, with molecular breakpoints that closely overlap our case. There are several rare clinical features shared between these three cases with similar breakpoints, including intention tremors of the hand, myoclonic jerks and bruxism, in addition to moderate developmental delay, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, and a social personality. To our knowledge, this is the third reported case of an interstitial 9p13.1–13.3 deletion. Given the few reported cases, there remains limited information regarding the phenotype of this condition and its long-term prognosis. Our case contributes to the growing data of the phenotype and natural history of this condition.

The patient was born at 39 weeks to a 31-year-old mother with a history of decreased fetal movements throughout the pregnancy. Delivery was via cesarean section due to fetal bradycardia. The baby required a 10-day stay in the neonatal intensive care unit for treatment for sepsis. Birth weight was 3,543 g (10th–50th centile), birth length was 50 cm (10th–50th centile), and head circumference was 35 cm (50th centile). The patient was born to non-consanguineous parents of Northern European descent. She had one older sister diagnosed with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and an otherwise unremarkable family history.

Her past medical history included a hospital admission at 3 months of age for failure to thrive related to poor feeding, and “stiffness” with no clear etiology identified. At 11 years of age, she continued to have significant feeding issues related to difficulty with chewing and swallowing and choking episodes, and she continued to only eat pureed foods. Extensive evaluations did not identify an etiology and she was noted to have oral hypersensitivities. She had no other hospitalizations or surgeries.

She had a long-standing history of tremor, first diagnosed at 3 years of age, although the age of onset was unclear. The tremor was postural in nature and worsened with stressful activities or anxiety. This symptom was a great source of frustration for the patient, often leading to behavioral meltdowns, as well, as impairing her fine motor abilities such as writing. The patient trialed clonazepam with worsening of behavioral symptoms, topirimate with significant side effects including pronounced mood swings and decreased appetite, and propanolol with minimal effect. Myoclonic jerks were noted at 6 years of age; however, at 11 years of age, were no longer an issue for the patient.

She had chronic issues with constipation and abdominal bloating, and a biopsy to assess for Hirschsprung disease was negative. Ophthalmology assessment identified hyperopia. Sleep was an issue with frequent nightmares; however, obstructive sleep apnea and night terrors were ruled out. She was also noted to have bruxism.

She was noted to have developmental delay during her admission at 3 months of age. Her developmental delays affected her language and fine motor skills more than gross motor skills. She started to walk at 15 months and at 11 years, she was able to mostly keep up with her peers. At 5 years of age, she had 150 words with only occasional two word sentences, and the ability to only understand two part commands. She had moderate-to-severe fine motor delay; however, her tremor has limited her ability to gain new skills. Neuropsychological testing at 11 years of age indicated a moderate cognitive disability, with her abilities similar to that of 3–4 years of age. Both her verbal and non-verbal skills were at the one percentile. Despite an overall social and interactive personality, the patient developed aggressive behaviors including hitting and vocalizations. Consultation with neuropsychiatry suggested that this may have been due to frustration due to the hand tremor as well as possible attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

The patient had a number of minor dysmorphic features (Figs. 1 and 2). Growth parameters at 11 years of age included a height of 132 cm (3rd–10th centile), weight 27.9 kg (3rd centile), and head circumference 52.5 cm (50th centile). The patient had a square face, full eyebrows that were not arched, and no synophyrys. She had normal eye spacing and palpebral fissure length and bilateral epicanthal folds. She had a broad nasal root. The philtrum and palate were normal. She had a thin upper lip. Her teeth were widely spaced. Her ears were borderline low-set and posteriorly angulated. Prominent veins on her chest and abdomen were observed. Palmar creases were normal, and there was no clindactyly of the fifth finger. She had abdominal distension, with diastasis rectus but no hepatosplenomegaly. Genitourinary exam revealed absent labia minora. She had keratosis pilaris underneath both eyebrows and anterior to the ears. She had freckling across the nasal bridge and cheeks. Pubertal development was not precocious. Neurologic features of the patient included bilateral coarse kinetic tremors and an otherwise normal neurological exam.

Investigations included an MRI at 2 years that showed delayed myelination, with mildly reduced periventricular white matter volume. An MRI at 11 years was normal. An ECG and ECHO at age 4 initially questioned mitral valve regurgitation and cardiomyopathy; however, with subsequent imaging, eventually reported as normal. An abdominal ultrasound at 13 years of age demonstrated normal kidneys, uterus, and ovaries. A muscle biopsy performed at 3 months of age because of an initial concern with stiffness was not diagnostic of a specific myopathy, including no report of nemaline bodies. It did demonstrate predominance of type 1 fibers and atrophic changes in type 2 fibers.

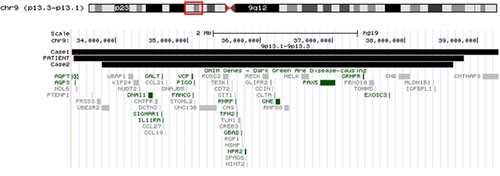

Array CGH analysis using the CytoSure ISCA 8 × 60K v2.0 platform (Oxford Gene Technology, Oxfordshire, UK) was performed in the Cytogenetics laboratory of the Alberta Children's Hospital and identified a deletion at 9p13.3p13.1 (33,422,520-38,815,471;hg19). This involved a deletion of 5.39 Mb in size and included over 90 genes, including 16 OMIM genes. Prior testing had been completed on a research basis in the Cytogenetics laboratory at the Children's and Women's Health Centre in Vancouver using the Affymetrix 500 whole genome SNP array. This was followed by fluorescence in situ hybridization using two home brew BAC probes from the Genome Science Center, mapping to 9p13.3; RP11-754H8 and RP11-655F16, which confirmed the deletion. Both parents were tested in the Vancouver laboratory and neither had this deletion.

We report the third case of an interstitial deletion with similar molecular breakpoints involving 9p13.1p13.3 [Niemi et al., 2012] (Fig. 3). Our patient was 11 years old and provides further information regarding long-term health issues.

Our patient shares features with the two previously reported cases (Supplementary Table SI), including developmental delay, ADHD, short stature, and low-set ears. Other clinical features that were seen in the three cases include a social personality and a hand tremor, the latter of which caused significant morbidity for two cases with multiple unsuccessful treatments attempted. The two most affected with hand tremor also exhibited myoclonic jerks, although this resolved in our patient by age 6 years. Bruxism, a relatively rare clinical finding, was reported in two of these cases. Our case had features that had not yet been reported to our knowledge. These included significant feeding difficulties with associated oral hypersensitivities and genital hypoplasia.

The interstitial deletion in our patient was 5.39 Mb in size and included over 90 genes and 16 OMIM genes. Figure 3 compares the OMIM genes deleted in our patient compared with the two similar cases published by Niemi et al. [2012]. Case 1 from Niemi et al. [2012] involved the largest deletion and had one additional gene deleted compared with our patient and case 2. This gene was AQP7, associated with an autosomal recessive condition associated with defects in glycerol release during exercise [Prudente et al., 2007]. Case 1 and our patient had the AQP3 gene deleted that was not deleted in case 2. That gene is involved in a red cell antigen blood disorder [Roudier et al., 2002]. These two genes are not likely related to the reported phenotypes of these cases.

The remaining OMIM genes were deleted in the three cases. Two genes, VCP and TMP2, are associated with autosomal dominant conditions; and two other genes, NPR2 and GNE, are associated with autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant conditions. VCP gene is associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 14, with or without frontotemporal dementia as well as inclusion body myopathy with early-onset Paget disease and frontotemporal dementia 1 [Nalbandian et al., 2011]. TMP2 gene is associated with distal arthrogryposis, type 2B, CAP myopathy 1, and nemaline myopathy 4 [Tajsharghi et al., 2012]. Our patient did not have classic features of these conditions that could have presented by age 11 years, including the neurological or bone changes. Her muscle biopsy report did not mention findings of inclusion bodies or nemaline bodies, however, there was a predominance of type one fibers that can be seen in nemaline myopathy. Feeding issues can be seen in nemaline myopathy related to facial and bulbar weakness, which may have contributed to her feeding issues, although this was not clearly established as the cause for her feeding issues and not clearly evident on her neurological examination.

The NPR2 gene is associated with epiphyseal chondrodysplasia, Miura type, which is an autosomal dominant condition [Miura et al., 2012]. Our patient did not have the skeletal features of this condition. GNE is associated with sialuria and is an autosomal dominant condition [Leroy et al., 2001]. Our patient did not have urine studies for sialic acid. None of these four autosomal dominant conditions clearly have associated tremor, bruxism, or genital hypoplasia that we could determine.

The other genes associated with autosomal recessive conditions did not clearly fit with her clinical features. DNAI1 is associated with primary ciliary dyskinesia; however, our patient did not have signs or symptoms of this disorder [Guichard et al., 2001]. SIGMAR1 gene is associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 16, juvenile spinal muscular atrophy type 2, frontal temporal dementia, and distal hereditary motor neuropathy [Al-Saif et al., 2011]. GALT gene is also one of the 16 OMIM genes included in the deletion, but our patient does not have galactosemia [Allderdice and Tedesco, 1975]. IL11RA gene is associated with craniosynostosis and dental anomalies. [Nieminen et al., 2011]. The gene RMRP is associated with anauxetic dysplasia, cartilage-hair hypoplasia, and metaphyseal dysplasia without hypotrichosis [Hsieh et al., 1989]. GBA2 is associated with spastic paraplegia 46 [Boukhris et al., 2010]. Our patient did not have symptoms consistent with either of these disorders. PAX5 gene is associated with a susceptibility to acute lymphoblastic leukemia [Ohno et al., 1990], and the gene GRHPR is associated with type II hyperoxaluria [Cramer et al., 1999]. EXOSC3 gene is associated with pontocerebellar hyploplasia; however, our patient had a normal MRI [Schwabova et al., 2013].

We report on a case with an interstitial deletion of 9p13.1p13.3 with molecularly defined breakpoints that closely overlap two previously reported cases, and who share similar clinical features of development delays, cognitive issues, and minor facial dysmorphisms, but otherwise healthy at the late childhood-adolescent age.