Work participation in adults with Marfan syndrome: Demographic characteristics, MFS related health symptoms, chronic pain, and fatigue

Abstract

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is a severe autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder that might influence peoples work ability. This cross sectional study aims to investigate work participation in adults with verified MFS diagnosis and to explore how the health related consequences of MFS and other factors might influence work participation. The prevalence of health problems in young adults compared to older adults with MFS was examined in association to work participation. A postal questionnaire including questions about work participation, demographic characteristics, MFS related health problems, chronic pain, and fatigue was sent to 117 adults with verified MFS (Ghent 1), and 62% answered. Fifty-nine percent were employed or students, significantly lower work participation than the General Norwegian Population (GNP), but higher than the Norwegian population of people with disability. Most young adults worked full-time despite extensive health problems, but the average age for leaving work was low. Few had received any work adaptations prior to retiring from work. In multiple logistic regression analysis, only age, lower educational level and severe fatigue were significantly associated with low work participation; not MFS related health problems or chronic pain. Fatigue appears to be the most challenging health problem to deal with in work, but the covariance is complex. Focus on vocational guidance early in life, more appropriate work adaptations, and psychosocial support might improve the possibility for sustaining in work for adults with MFS. More research about work challenges in adults with MFS is needed. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is an autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder caused by mutations in the fibrillin one gene, diagnosed by the Ghent 1 and Ghent 2 diagnostic criteria [De Paepe et al., 1996; Loeys et al., 2010]. The most life threatening complication is dilation and dissection of the aorta. The condition also affects the skeletal, skin/integumentary, pulmonary, and dura as well as visual problems due to lens dislocation, which entails risk for retinal detachment [Maumenee, 1981; De Paepe et al., 1996; Pyeritz, 1996, 2007; Loeys et al., 2010; Drolsum et al., 2015].

Medications aimed at reducing blood pressure and heart rate are used to prevent the dilation of arteries. Many patients are advised to refrain from contact sports and to limit their physical exertion to reduce the risk of aortic dilatation and lens dislocation [Loeys et al., 2010], which may lead to inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle [Rand-Hendriksen et al., 2010]. In addition, chronic pain, fatigue, sore joints, and reduced physical capacity and endurance are commonly reported by persons with MFS [Peters et al., 2001b, 2002; Hasan et al., 2007; Rand-Hendriksen et al., 2010; Bathen et al., 2014; Nelson et al., 2015].

Work plays an important role in most adult's lives, and in Norway persons of age 20–67 are expected to work or study [Lidal et al., 2009; NSD, 2015]. Being employed is associated with better self-esteem, higher life satisfaction, and improved well-being [Lidal et al., 2009; NSD, 2015]. Studies report that adults with MFS may experience significant psychical limitations that interfere with daily life function and impose a burden on daily life, school attendance, work opportunities, and social interaction [Van Tongerloo and De Paepe, 1998; De Bie et al., 2004; Peters et al., 2005; Fusar-Poli et al., 2008; Velvin et al., 2015]. Being bullied, teased, and stigmatized in school and at work, suffering in the workplace, remaining in a dissatisfying job, limited occupational choices because of the disease [Van Tongerloo and De Paepe, 1998; Peters et al., 2005] and leaving work earlier than the general population are reported [De Bie et al., 2004].

Only five papers are identified dealing partly with work participation in adults with MFS, indicating that approximately 60% of adults with MFS are working full or part-time [Van Tongerloo and De Paepe, 1998; De Bie et al., 2004; Peters et al., 2005; Fusar-Poli et al., 2008; Bathen et al., 2014]. None of these studies explored the association between work participation and different MFS-related health problems (aorta dilatation, aortic dissection, aorta operation, and visual problems), pain, fatigue, and demographic factors.

Given the complexity of MFS, several factors might influence peoples work participation.

This study aims to investigate work participation in adults in the age of 20–67 years with verified MFS diagnosis and explore how health related consequences of MFS and other factors influence work participation. In addition, describe the prevalence of health problems in young adults with MFS (≤ 39 years) compared to those of older adults with MFS (≥ 40 years), in association with work participation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross sectional postal questionnaire study is part of a larger study on psychosocial aspects in adults with Marfan syndrome. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in South-eastern Norway and by the Data Protection Officer at Oslo University Hospital. Permission was given to collect and analyze anonymous questionnaire data.

Participants and Procedure

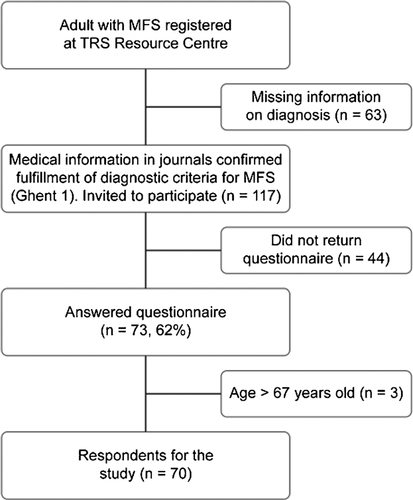

In 2010, all the medical journals of patients registered with MFS at the TRS National Resource Centre for Rare Disorders in Norway, age 20 years and above (n = 180) were examined. Patients fulfilling the Ghent 1 criteria (the available criteria at that time) (n = 117) were invited to participate. In an earlier study [Rand-Hendriksen, 2010a], 87 persons were found to fulfill the Gent-1 criteria, 73 of them carrying a supposed disease giving variant in FBN1. Sequencing of the genes TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 showed that one person fulfilling Ghent 1 carried a TGFBR1 mutation and one person fulfilling Ghent 1 carried a TGFBR2 mutation. These two persons were taken out, while the 85 persons were among the 117 persons invited. Among the last 32 persons invited, there may be persons carrying one of the five Loeys–Dietz genes fulfilling the Ghent-1 criteria.

A letter was mailed including an informed consent form, questionnaire, and a prepaid return-addressed envelope. Seventy-three individuals returned the questionnaire (response rate 62%). Only patients in the age groups 20–67 years (n = 70) were included in this article, due to that the normal working-age is between 20 and 67 years in Norway. Figure 1 shows a flow chat of recruitment of the participants.

Assessment Methods

A study-specific questionnaire including questions about demographic characteristics, MFS-related health problems, chronic pain, and fatigue was designed. The questionnaire was subsequently evaluated in a pilot study (unpublished data).

To measure work participation, questions from the “National Labor Force Survey in Norway” [SSB, 2010] were used, including questions about present employment status, occupation, degree of disability pension, and age of withdrawal from work. In addition, questions about work challenges and work adaptations were included. Work participation was categorized as follows: employed (paid work), student, rehabilitation pension, and disability pension. For analytical purposes, the variables were dichotomized into two groups: (1) “Work disability” (receiving disability pension or rehabilitation pension)1 (2) “Working” (employees/students).

The questionnaire included demographic questions (i.e., gender, age, age of MFS diagnosis, education level (</≥ 13 years), being married/living with a partner and having children), MFS-related health problems (i.e., aortic dilation, aortic dissection, prior aortic surgery, and visual problems due to lens dislocation or retinal detachment, use of blood pressure medicine, and recommend physical restrictions), chronic pain, and fatigue. The Standardized Nordic Questionnaire” [Kuorinka et al., 1987; Svebak et al., 2006], which measure the presence, location, and impact of musculoskeletal chronic pain, was used to measure chronic pain. In this publication, the question: “During the last year, have you continuously suffered from pain or stiffness in the muscles and joints for at least 3 months” from this questionnaire was used.

Fatigue was assessed with the “Fatigue Severity Scale” (FSS). FFS is a nine-item questionnaire developed to measure the impact of fatigue on daily functioning [Krupp et al., 1989; Whitehead, 2009], each item scored on a seven-point Likert scale. To assess the prevalence of “severe fatigue” versus “no fatigue” the following cut-off values were used; non-fatigue = FFS mean score ≤ 4 and severe fatigue = FFS mean score ≥ 5 [Roelcke et al., 1997; Lerdal et al., 2005]. To compare the extent of health problems between younger and older adults with MFS, a cut-off age between young and old adults with MFS were set to 40 years old, similar to the cut-off age used in a large study of work participation for the general population in Norway [NSD, 2011].

Data Analysis

The data were summarized using frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations (SD), with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Due to the small sample size, the primary statistical analyses were corroborated with alternative statistical analyses to ensure the robustness of the results [Parker et al., 2004]. Spearman's rank order correlations were applied to compare categorical variables, and Mann Whitney U-test were performed when appropriate on continuous variables. Univariate logistic regression analyses were used to explore the association between the dependent variable and each of several explanatory variables.

Variables that were significantly associated in the univariate logistic regression analysis were entered simultaneously in to a multivariate logistic regression analysis. The strength of the association was expressed as odds ratio (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). SPSS version 21 was used for data handling and the statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two- tailed, and the significance level was set at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic Factors

The mean age was 43 years (range 20–67 years), 57% were women. No significant difference were observed between respondents and non-respondents in terms of gender (68% women), or age (mean = 40 years, range 20–67). Fifty-four percent of the respondents reported completing a formal education of 13 years or more. Fifty-nine percent were employed/students and 41% had disability/rehabilitation pensions. No individuals were unemployed, home workers, etc. The median age for leaving work/receiving disability pension was 41 years (range 23–67).

Table I displays the respondent's socio-demographic characteristics, and prevalence of Marfan-related health problems, chronic pain, and fatigue.

| Variables | MFS (N = 70) Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic features | |||

| Age in years | 43 (13,1) | 20–67 | |

| Age of MFS (n = 67)* | 23 (14,9) | 1–56 | |

| N (%) | |||

| Women | 40 (57) | ||

| Living with adult partner | 42 (68) | ||

| Own children | 35 (50) | ||

| Educational level (highest finished education) > 13 years | 38 (54) | ||

| Employment status | |||

| Employed full time | 28 (41) | ||

| Employed part-time | 9 (12) | ||

| Student | 5 (6) | ||

| Disability pension (graded) | 5 (7) | ||

| Disability/rehabilitation pension 100% | 24 (34) | ||

| Marfan related health problems | |||

| Dilated aorta | 64 (91) | ||

| Aortic dissection | 24 (33) | ||

| Operation aorta/other blood vessels | 40 (57) | ||

| Visual impairment due to lens dislocation/retinal detachment | 23 (33) | ||

| Advised physical restrictions | 47 (67) | ||

| Use of blood pressure medication | 46 (66) | ||

| Chronic pain | 44 (63) | ||

| Fatigue ≥ 5 | 27 (39) | ||

- * Four persons did not the age at diagnosis.

Table II shows how the respondents′ experienced that MFS related health problems influenced work participation, work ability, and personal economy (Table II).

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Unsure (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All participants (n = 70)a | |||

| Does the diagnosis of MFS influence your work ability? | 49 | 45 | 6 |

| Does the diagnosis of MFS influence your financial situation? | 41 | 41 | 18 |

| People working/student/etc. (n = 41)b | |||

| Do your health problems limit your execution of your work? | 47 | 49 | 4 |

| Do your health problems limit your capacity to work? | 41 | 56 | 3 |

| People with disability pension (n = 29)c | |||

| Did the diagnosis of MFS influence retirement to disability/rehabilitation pension? | 80 | 5 | 15 |

| If yes, was it because the work was to physical hard? | 73 | 10 | 17 |

| Did you receive any work task or work place adaptation prior to disability pension? | 25 | 60 | 15 |

- a All participants answered question about experiences of working.

- b Persons who were working/student answered questions about their current experience of working.

- c People on disability pensions were asked questions about how the diagnosis influenced leaving work.

Table III shows that both young adults (≤ 39 years) and older adults (≥ 40 years) exhibit extensive health problems. Younger adults (≤ 39 years) demonstrate a lower incidence of health-related symptoms than older adults with MFS (≥ 40 years), except for chronic pain. Only differences in aortic dissection and operations of the aorta and other blood vessels were statistically significant.

| MFS health related variables and Pain and Fatigue (n = 70) | 20–39 years (%) | 40–67 years (%) | r (rho) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilated aorta (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 14.8 | 4.7 | 0.177 | 0.139 |

| Yes | 85.2 | 95.3 | ||

| Aorta dissection (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 70.4 | 42.2 | 0.269 | 0.019* |

| Yes | 29.6 | 57.1 | ||

| Aorta operation/other blood vessels (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 55.6 | 31.0 | 0.245 | 0.040* |

| Yes | 44.4 | 69.0 | ||

| Visual problems due to MFS (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 72.0 | 62.8 | 0.094 | 0.439 |

| Yes | 28.0 | 37.2 | ||

| Blood pressure medicine (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 51.9 | 23.3 | 0.293 | 0.014* |

| Yes | 48.1 | 76.7 | ||

| Advised physical limitations (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 30.8 | 27.9 | 0.031 | 0.800 |

| Yes | 69.2 | 72.1 | ||

| Chronic pain (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 37.0 | 37.2 | 0.002 | 0.988 |

| Yes | 63.0 | 62.8 | ||

| Fatigue (n = 70) | ||||

| <5 | 66.7 | 57.1 | 0.095 | 0.429 |

| ≥5 | 33.3 | 42.9 | ||

Only educational level, age, and fatigue correlated significantly to work participation in the initial bivariate analysis (Table IV).

| Independent variables | Disability pensions (n = 29) | Working etc (n = 41) | r | P-value (two-tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristic | ||||

| Age (n = 70) | ||||

| 20–39 | 15.6 | 57.7 | −0.424 | < 0.001* |

| 40–69 | 84.4 | 46.3 | ||

| Gender (n = 70) | ||||

| Male | 34.4 | 48.2 | 0.142 | 0.240 |

| Female | 65.6 | 51.8 | ||

| Living alone/with partner (n = 69) | ||||

| Living alone | 38.7 | 22.0 | 0.223 | 0.065 |

| Living with adult partner | 61.3 | 78.0 | ||

| Own children (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 41.9 | 51.2 | 0.047 | 0.701 |

| Yes | 58.1 | 48.2 | ||

| Educational level (n = 70) | ||||

| <13 years | 84.4 | 31.7 | 0.504 | <0.001* |

| >13 years) | 15.6 | 65.3 | ||

| Age of diagnosis (n = 68) | ||||

| <25 | 42.9 | 57.5 | 0.191 | 0.125 |

| >26 | 57.1 | 42.5 | ||

| Marfan related symptoms | ||||

| Dilated aorta (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 6.5 | 12.2 | −0.154 | 0.203 |

| Yes | 93.5 | 87.8 | ||

| Aorta dissection (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 58.1 | 39.0 | −0.178 | 0.142 |

| Yes | 41.9 | 61.0 | ||

| Operation of aorta or other blood vessels (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 35.5 | 43.9 | −0.082 | 0.504 |

| Yes | 64.5 | 56.1 | ||

| Visual problems due to MFS (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 59.4 | 69.2 | −0.75 | 0.544 |

| Yes | 40.6 | 30.8 | ||

| Advised physical limitations(n = 70) | ||||

| No | 67.7 | 73.2 | 0.058 | 0.639 |

| Yes | 32.3 | 26.8 | ||

| Use of Blood pressure medication(n = 70) | ||||

| Yes (N=49) | 25.0 | 39.0 | 0.119 | 0.328 |

| No (N=24) | 75.0 | 61.0 | ||

| Chronic pain (n = 70) | ||||

| No | 25.0 | 43.9 | −0.166 | 0.167 |

| Yes | 75.0 | 56.1 | ||

| Fatigue (n = 70) | ||||

| <5) | 41.9 | 70.7 | −0.353 | 0.003* |

| ≥5 | 58.1 | 29.3 | ||

- * Significant.

Demographic and MFS-related variables, pain, and fatigue were included in the univariate logistic regression analysis. Three variables demonstrated significant association with reduced work participation; age (P < 0.001), educational level (P < 0.001), and fatigue (P = 0.005). When entered simultaneously in the multiple logistic regression analysis, increased age, lower educational levels, and higher levels of fatigue were associated with leaving the workforce before 67 years of age (P = 0.013, P = 0.001, and P = 0.023, respectively) (Table V). The strongest predictor was educational level, resulting in an odds ratio of 9.82. This finding indicates that people with higher education levels are nearly ten times more likely to be working than those with lower educational levels, when controlling for each of the other factors in the model. The odds ratio of 0.931 for age was less than 1, indicating that work participation decrease with increasing age. Higher degrees of fatigue indicated a lower likelihood of working (Table V).

| Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate regression analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | OR (Exp β) | 95%CI | P-value | OR (Exp β) | 95% CI | P-value |

| Demographic characteristic | ||||||

| Age | 0.926 | 0.880–0.969 | <0.001 | 0.931 | 0.880–0.985 | 0.013 |

| Gender | 1.810 | 0.679–4.824 | 0.236 | |||

| Living alone/with partner | 0.375 | 0.131–1.074 | 0.068 | |||

| Own children | 1.615 | 0.315–2.161 | 0.690 | |||

| Educational level | 10.338 | 3.220–33.199 | <0.001 | 9.824 | 2.605–37.044 | 0.001 |

| Age of diagnosis | 0.974 | 0.941–1.008 | 0.131 | |||

| Marfan related symptoms | ||||||

| Aortic dilation | 0.257 | 0.28–2.328 | 0.227 | |||

| Aortic dissection | 0.480 | 0.181–1.275 | 0.141 | |||

| Aortic/blood vessels surgery | 0.710 | 0.264–1.908 | 0.497 | |||

| Blood pressure medicine | 0.595 | 0.213–1.664 | 0.326 | |||

| Recommended physical limitations | 1.292 | 0.451–3.698 | 0.633 | |||

| Visual problems due to MFS | 0.727 | 0.264–2.002 | 0.538 | |||

| Chronic pain | 0.487 | 0.175–1.352 | 0.167 | |||

| Fatigue (mean score) | 0.549 | 0.360–0.837 | 0.005 | 0.550 | 0.328–0.920 | 0.023 |

- Age in years; gender: women = 0, men = 1; living alone/partner: living alone = 0, living with partner=1; having own children: no=0, yes = 1; educational level (highest finished education) 0 ≤ 13 years, 1 ≥ 13 years; age of diagnose in years; aortic dilation: 0 = no, 1=yes, aortic dissection: o = no, 1 = yes; use of blood pressure medicine: 0 = no, 1 = yes; Recommended physical limitations: 0 = no, 1 = yes; visual problems: 0 = no, 1 = yes; chronic pain:0 = no, 1 = yes; fatigue mean score.

The multiple logistic regression model containing all predictors was statistically significant with X2 (7, N = 70)= 39.3 and P < 0.001, indicating that the model was able to distinguish between respondents who reported receiving disability/rehabilitation pension and those who were working. The final multiple logistic regression model explained 41.4% (Cox and Snell R Squared) to 58.2% (Nagelkerke R Square) of the variance in work participation.2

DISCUSSION

The main findings of the study showed that many adults with MFS met challenges in work participation. The average educational level was high, and most young adults worked full-time despite extensive health problems. However, the average age for leaving work was very low. In the logistic regression analysis the odds of not-participating in work were significantly higher in persons with lower educational level, older age, and higher level of fatigue, but no significant association was found with other demographic characteristics, MFS-related health consequences, and chronic pain.

Education and Work Participation

Education is an important factor in obtaining and retaining employment [Borg, 2008] and may provide the opportunity to choose more suitable work in accordance with an individual's physical function and capacity. The high education level in the MFS group is in line with findings from other groups of diseases [Johansen et al., 2007; Wekre et al., 2010], and that adults with MFS have no problem obtaining a higher education [De Bie et al., 2004]. This finding is also in line with a study of Peters et al. [2005] that found that 51% of the respondents with MFS endorsed the use of education as a coping strategy. Compared to the general population in Norway (GNP) it seems that the MFS group has higher average education level, which also is in line with former research among other groups with physical limitations [Johansen et al., 2007; Wekre et al., 2010]. An explanation might be that adolescents and young adults with MFS with bodily physical limitations might concentrate more on intellectual work, rather than physical activities.

Although the educational level was high, the work participation among our study group are significantly lower than the GNP (79% are employed) [NSD, 2011, 2015], but higher than the “general disability group” (GDG) in Norway (43% are employed) [NSD, 2011, 2015]. This difference indicates that the health problems associated with MFS may influence work participation more than education, especially compared to the GNP, but less compared to GDG.

Aging and Work Participation

In the study group most young adults (<39 years) with MFS worked full-time, indicating that they may encounter few problems entering the labor market and in maintaining a full job. On the other hand, most participants reported that their health problems limited their ability to work, which is in line with other studies reporting that MFS interfered with daily life and with work participation [Van Tongerloo and De Paepe, 1998; Peters et al., 2005; Fusar-Poli et al., 2008]. It is also similar to the findings of De Bie et al. [2004] which indicated that approximately 34% of adults with MFS above 25 years of age reported it physically impossible to work.

In our study, most of the respondents worked full-time or received a full disability pension. Few participants worked part-time, using little de-escalation, and few reported any type of workplace adaptation before they received disability pension. The physical limitations of MFS are rarely visible and studies of other patient groups [Goffman, 1990; Maynard and Roller, 1991] with invisible diseases indicate that many patients push themselves to their limits to manage full-time work and to maintain a normal life. These individuals try to pass as non disabled, to hide their disability, and might therefore ignore their disability mentally and physically, and not communicate their needs for adaptation's [Goffman, 1990; Maynard and Roller, 1991]. Both our, and former results might indicate that many young adults with MFS strive to maintain full time work, despite extensive health problems. This renders the acceptance and expression of one's needs difficult, and might explain why few received any kind of work adaptations before leaving work.

The average age for leaving work in the study group was 41 years old, significantly lower than the GNP. This is in line with De Bie et al. [2004] who found that work participation for people with MFS decreased earlier than for the general population. Studies of other patient groups report similar findings; indicating that due to increased health problems, the employment rate declines more rapidly, and more extensively in individuals with disabilities than in people without disabilities [Johansen et al., 2007; Wekre et al., 2010].

Hasan et al., [2007] found that MFS patients above 50 years of age had a significantly higher degree of health-problems than a healthy control group without MFS. However, verification of the diagnosis in accordance with diagnostic criteria was not done and their study did not compare older and younger people with MFS. In our study, both young (< 39 years), and older (≥ 40 years) age groups reported extensive health problems. The incidence of almost all health problems were higher in the oldest age group, and may be part of the explanation for the group differences according to age and work participation.

Health Problems and Work Participation

We had expected significant associations between work participation and MFS-related health problems such as dilated aorta, aortic dissection and aortic operations, visual problems, and also chronic pain. In the literature, the severity of MFS seems to be associated mainly with the disease's cardiovascular manifestations [De Bie et al., 2004; Rand-Hendriksen et al., 2010]. No significant associations between cardiovascular manifestations or other MFS-related health problems and work participation were found. The cardiovascular manifestations may be underestimated by the patients as long as they do not experience any subjective ailments [De Bie et al., 2004], and aortic dilation usually does not cause subjective ailments [Rand-Hendriksen et al., 2010; Rand-Hendriksen, 2010a].

In a small study of Van Tongerloo and De Paepe [1998] visual deficiency was reported to be the greatest disadvantage in work participation. No significant association was found in our study. One explanation may be that eye surgery has improved and that it is possible to some extent to compensate for visual problems with optic devices, digital magnification programs, and glasses. Based on our clinical experiences it also seems that many adults with MFS have found ways to handle their visual problems, particularly those who have had reduced vision from childhood.

Chronic pain has been found to affect occupational activity and work participation among other patient groups [Mc Cracken et al., 2004; Steen, 2013]. No association was found in our study group. Studies indicate that the prevalence of chronic pain in MFS is high [Graham and Pyeritz, 1995; Peters et al., 2001b; Foran et al., 2005; Dean, 2007; Jones et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 2015], and none studies have explored the association between chronic pain and work. Our clinical experience is that many persons with MFS engage in life activities despite having chronic pain, and many seem to accept the pain as a symptom of a severe disease.

Severe fatigue was the only health problem that was significantly associated with work participation in our study group. As far as we know, this is the first study that has examined the association between work participation and fatigue in MFS. Knowledge about aspects that may influence fatigue in MFS is still sparse, and the results from previous studies are conflicting [Bathen et al., 2014]. However, fatigue is found to play a major role in daily life for many people with hereditary connective tissue disorders such as MFS and EDS [Peters et al., 2001a,2001b; Percheron et al., 2007; Rand-Hendriksen et al., 2007; Van Dijk et al., 2008; Voermans et al., 2010; Celletti et al., 2013]. Studies indicate that chronic pain [Bathen et al., 2014], orthostatic intolerance [Van Dijk et al., 2008], and psychological aspects [Rand-Hendriksen et al., 2007] are associated to severe fatigue in MFS.

One study found that use of blood pressure medication [Peters et al., 2001a] was associated with fatigue, but another study found no such significant association [Bathen et al., 2014]. Therefore, the association between blood pressure medication and fatigue in MFS is unclear. In our questionnaire, we did not ask about different types of antihypertensive medication. It is however important to consider that blood pressure medication in some patients may amplify dysautonomic symptoms and orthostatic intolerance and therefore maybe increase the experience of fatigue [Van Dijk et al., 2008]. Severe fatigue is common in the GNP, as well, but with a prevalence of 22% [Lerdal et al., 2005] compared to 41% [Bathen et al., 2014] in the MFS population, the MFS's prevalence is significantly higher. Similar studies of fatigue in the work force in USA and Europe indicate that severe fatigue is a potentially disabling condition that impairs people's ability to accomplish tasks and also impair concentration [Ricci et al., 2007; Harder et al., 2012; Van der Hiele et al., 2014].

Studies have also found that it is difficult to establish appropriate adaptations for people with fatigue in the work place [Ricci et al., 2007; Harder et al., 2012]. According to Loge et al. [1998] work participation is associated with lower degree of fatigue. In light of this the differences in work participation between the MFS and GNP make sense.

Our study indicated that only educational level, age, and fatigue were significantly associated to work participation, but the relatively small sample size might lead to a reduction in the statistically power for some of the more advanced analyses. The total number of MFS patients in Norway is unknown: hence it is uncertain whether the respondents were representative for the total MFS population in Norway.

Implication for Further Research

The study has shown that having MFS may influence peoples work participation, but that the associations are complex, and more explorations are needed.

Our study was cross-sectional; hence, we could not explore causal associations. The logistic regression model of work participation explained 44.4% (Cox and Snell R-squared) to 58.2% (Nagel R-squared) of the variation in work participation through the included factors. This result implies that other and unknown factors significantly affect work participation in adults with MFS. Psychological aspects, such as depression, anxiety and coping [NIPH, 2012; Bertilsson et al., 2013] and engaging in physical activities [Harder et al., 2012] have been found to be significantly associated with work participation in other patients groups, and should be in focus of further research in MFS. Organizational work-related factors might also be of interest, including type of job, job-strain, work-related fear avoidance, job tenure, and work-place accommodation as underscored as important factors among other groups of participants [Achterberg et al., 2012; Harder et al., 2012; Hogan et al., 2012; Van der Hiele et al., 2014].

We suggest a mixed-method approach, combining quantitative and qualitative methods on a larger group of patients with verified diagnosis. This may give a broader and deeper understanding of how people with MFS experience work participation and how they consider education, coping with MFS related health problems, chronic pain, and fatigue as important for work participation. International collaborative studies, using the same study design and validated tools are recommended, due to the possibility to enhance the quality of the study by securing sufficient size of the study population and comparing the results between different countries.

Implications for Clinical Practice

A greater focus on vocational guidance early in life, use of adaptations in work situations, psychosocial support, and strategies to deal with fatigue and pain might support people with MFS to cope with daily life and work, and hopefully delay early retirement. Acceptance of limitations, realistic expectations, and accurate knowledge are found as important for coping in adults with MFS [Peters et al., 2001a; Giarelli et al., 2008]. More knowledge about fatigue in MFS and helping people developing strategies for coping with fatigue might be important. Rehabilitation for people with MFS has been sparse. In the future, programs for adolescents and adults with MFS should emphasize educational and work aspects. Treatment options should be directed at the symptoms in accordance to the individual situation as part of an interdisciplinary approach. Asking about education, work and associated factors like fatigue, chronic pain, and other life aspects should be a routine when examining MFS patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to thank the Norwegian Marfan association Norway, all the participants, the Sophie's Minde Foundation and TRS National Resource Centre for Rare Disorders, Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital, Norway, who made this study possible.