Myhre syndrome: Clinical features and restrictive cardiopulmonary complications

Abstract

Myhre syndrome, a connective tissue disorder characterized by deafness, restricted joint movement, compact body habitus, and distinctive craniofacial and skeletal features, is caused by heterozygous mutations in SMAD4. Cardiac manifestations reported to date have included patent ductus arteriosus, septal defects, aortic coarctation and pericarditis. We present five previously unreported patients with Myhre syndrome. Despite varied clinical phenotypes all had significant cardiac and/or pulmonary pathology and abnormal wound healing. Included herein is the first report of cardiac transplantation in patients with Myhre syndrome. A progressive and markedly abnormal fibroproliferative response to surgical intervention is a newly delineated complication that occurred in all patients and contributes to our understanding of the natural history of this disorder. We recommend routine cardiopulmonary surveillance for patients with Myhre syndrome. Surgical intervention should be approached with extreme caution and with as little invasion as possible as the propensity to develop fibrosis/scar tissue is dramatic and can cause significant morbidity and mortality. © 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Over 30 years ago Myhre and colleagues described a syndrome characterized by deafness, dysmorphic facial features, thick or stiff skin, restrictive joint movement, skeletal anomalies, and short stature with muscular/thick-appearing or “compact” body habitus [Myhre et al., 1981]. Subsequent to the original publication, others have further defined the facial, skeletal, respiratory and upper airway features of the syndrome and have expanded the clinical phenotype to include variable neurodevelopmental features [Titomanlio et al., 2001; Burglen et al., 2003; Lopez-Cardona et al., 2004; Rulli et al., 2004; Bachmann-Gagescu et al., 2011; McGowen et al., 2011]. In 2011, the genetic basis for Myhre syndrome was identified with documentation of mutations within a very restricted range of SMAD4 [Caputo et al., 2012; Le Goff et al., 2012]. To date, SMAD4 mutations have been reported in 46 patients with Myhre syndrome (OMIM #139210) [Al Ageeli et al., 2012; Asakura et al., 2012; Caputo et al., 2012; Le Goff et al., 2012; Lindor et al., 2012; Picco et al., 2012; Ishibashi et al., 2014; Kenis et al., 2014; Michot et al., 2014; Hawkes et al., 2015; Oldenburg et al., 2015] with no report of a familial case. While the clinical picture of Myhre syndrome has been further clarified with new reports of molecularly proven cases, there remains a paucity of data on the cardiopulmonary aspects of the disorder, which may be progressive and fatal. We report five new Myhre syndrome patients with SMAD4 mutations, three of whom died of severe cardiac disease, and provide delineation of the associated fibrotic complications.

CLINICAL REPORTS

Patient 1

The patient was born small for gestational age (SGA) at term to healthy, nonconsanguineous 29 year old parents. When seen for initial genetic evaluation as a toddler she was noted to have progressive conductive hearing loss, mild developmental delay, dysmorphic craniofacial features, recurrent choanal stenosis, short stature, hyperopia, advanced bone age, 11 rib pairs, dermal thickening and compact build (Fig. 1). Echocardiogram at that time demonstrated a moderate-sized secundum atrial septal defect (ASD) but no valvar abnormalities. Genetic studies at this time included a normal 46,XX karyotype, normal 180 K microarray (hg 18), and normal CREBBP sequencing. On routine cardiac followup at one year of age the patient was noted to have a small ASD and no other cardiac defects. At seven years of age the patient was evaluated for a new murmur with symptoms of heart failure. Echocardiography at that time demonstrated polyvalvar thickening with moderate mitral valvar stenosis and normal subvalvar apparatus, mild mitral regurgitation, a trileaflet aortic valve with moderate aortic stenosis, mild aortic regurgitation, concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), mild tricuspid insufficiency and a diffusely small aortic arch without focal narrowing. Further genetic studies included normal sequencing of ADAMTSL2 and FBN1 as well as deletion/duplication analysis. Targeted sequencing of SMAD4 then revealed a c.1499T > C (p.Ile500Thr) mutation.

The patient developed rapid progression of her aortic stenosis and four months later underwent cardiac catheterization. At catheterization, the valve appeared rubbery and dysplastic with easy resolution of narrowing on balloon inflation. However, due to the rubbery nature of the valve, no reduction in gradient could be achieved with a standard-sized balloon. A result was achieved after a second valvuloplasty with a larger balloon with a fall in the peak to peak gradient from 50 to 20 mmHg. The improvement, however, was quite transient. Both right and left ventricular end-diastolic pressures were elevated at 15 mmHg, consistent with mild to moderate restrictive physiology. One month following the procedure the patient was again documented to have progressive aortic valvar stenosis as well as mitral stenosis. Eight months following aortic valvuloplasty the patient underwent surgical aortic valve repair, tricuspid valvuloplasty, ASD closure and mitral valve replacement following a failed attempt at mitral valve repair. The mitral valve was characterized by severe fibrosis and dystrophic calcification of the leaflets and subvalvar apparatus. Aortic valvar, subvalvar and supravalvar fibrosis and calcification were also noted with fibrotic tissue partially covering the right coronary ostia. The tricuspid valve was not fibrotic but had a dysplastic cleft in the anterior leaflet. Surgery was complicated by complete heart block requiring pacemaker placement on postoperative day 10. At the time of pacemaker placement the midline fascia below the sternotomy was noted to be abnormally thickened. In addition, the epicardial surface of the heart was noted to be unusually rubbery and fibrotic. Over the next two months the patient developed progressive heart failure secondary to a restrictive cardiomyopathy culminating in sudden cardiac arrest and placement on extracorporeal membrane oxygenator (ECMO). Left atrial pressure was markedly elevated at 35mmHg despite a functioning, appropriately-sized mechanical mitral valve. Cardiac catheterization was performed for the purposes of creating an ASD for left heart decompression. Left ventricular function remained severely impaired and the patient underwent cardiac transplantation. Cardiac transplantation was complicated by inability to oxygenate requiring ECMO support for one week, inability to obtain chest closure despite an appropriately-sized donor heart, progressive SVC anastomotic narrowing requiring stenting, respiratory failure with inability to wean from the ventilator, and progressive low cardiac output without evidence of rejection requiring repeat ECMO support two months post transplantation. The patient suffered an intracerebral bleed while on ECMO support and care was withdrawn. She was 8 years old.

Patient 2

The patient was the second child of healthy, nonconsanguineous parents (maternal age 29 years; paternal age 37 years). She was born SGA at term. The pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and prenatally diagnosed duodenal atresia. The intestinal defect was repaired on the first day of life. Routine echocardiogram demonstrated mild coarctation of the aorta. The subsequent clinical course was characterized by dysmorphic craniofacial features (Fig. 2), persistent short stature, velopharyngeal insufficiency requiring a palatal lengthening procedure, recurrent ear infections requiring placement of multiple sets of bilateral myringotomy tubes, and superimposed bilateral sensorineural hearing loss resulting in severe speech delay. Overall development was mildly delayed. Skeletal survey showed a narrow sciatic notch, short metacarpals and 11 rib pairs. At seven years of age the aortic coarctation was refractory to balloon angioplasty, for which she underwent stent placement. Despite adequate relief of aortic arch obstruction, the patient developed elevation in pulmonary vascular resistance and was subsequently diagnosed with restrictive cardiomyopathy, interstitial lung disease, and pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary function testing revealed a severely reduced FEV1 with no response to bronchodilator therapy. Open lung biopsy was performed at 10 years of age which demonstrated diffuse interstitial fibrosis, medial thickening of arteries, arterioles and veins and smooth muscle hyperplasia of the airways with a large amount of collagen present. She had progression of her restrictive cardiomyopathy over a period of three years and underwent bilateral heart and lung transplantation. Transplantation was complicated by diffuse mediastinal fibrosis (pericardium was noted to be normal) and adhesions requiring extensive care in removing. Post-transplant her chest was able to be closed, however, she suffered persistent respiratory failure and blood pressure lability. She suffered an ECMO-related stroke and died 6 days postoperatively at 12 years of age.

The explanted heart demonstrated no abnormality of the pericardium but diffuse fibrosis of the endocardium and subendocardium. Explanted lungs demonstrated diffuse interstitial fibrosis with septal widening and pneumocyte hyperplasia. SMAD4 sequencing performed post-mortem from previously extracted DNA for other genetic studies (46,XX karyotype, 22q11.2 FISH, chromosome breakage studies, Feingold studies [MYCN sequencing and deletion/duplication analysis]), confirmed a c.1499T>C (p.Ile500Thr) mutation consistent with the diagnosis of Myhre syndrome.

Patient 3

The patient was born SGA to nonconsanguineous parents at term (maternal age 28 years; paternal age 30 years). The clinical course was marked by dysmorphic craniofacial features (Fig. 3) significant feeding and swallowing difficulties as an infant. At 24 months she charted at below the 5th centile for stature; approximately the 50th centile for a 10 month old. Her upper airway was thoroughly evaluated and no obstruction was found, although absent nasal cilia were noted. Over time she had persistence of short stature, progressive conductive hearing loss, progressive skin changes marked by dermal thickening, menorrhagia refractory to medical therapy, and at age 17 presented with unilateral vision loss due to biopsy-confirmed right optic nerve sheath meningioma. The patient had normal intelligence, but required medical treatment of obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders. Her initial cardiac evaluation was performed at age two years at which time she was diagnosed with an innocent murmur with normal echocardiogram. A repeat echocardiogram at age four years documented normal cardiac anatomy. At age 16 she was again evaluated by cardiology for dyspnea and hypertension. Spirometry revealed moderate to severe restrictive lung disease which was felt to be secondary to musculoskeletal deformity due to her dwarfism. Echocardiogram documented mild aortic stenosis and normal ventricular function. Hypertension was well controlled on two medical agents.

Over a period of eight years her aortic valve stenosis became progressively more severe with a peak to peak gradient of 80 mmHg. Aortic balloon valvuloplasty was performed. This also required upsizing of the balloon, with the valve appearing dysplastic. A reduction in gradient from 80 to 35 mmHg was achieved. The patient had persistent elevation of both right- and left-sided filling pressures consistent with restrictive physiology. Myhre syndrome was diagnosed at this time with confirmation of a c.1498A > G (p.Ile500Val) mutation in SMAD4. Over the ensuing two years the patient developed progressive shortness of breath with LVH and progressive aortic stenosis requiring repeat valvuloplasty attempt at age 26 years. Just prior to her catheterization she was unable to walk across the room or eat a meal without distress. At catheterization, the anesthesia team found her respiratory mechanics to be significantly compromised and counselled the family that she may not tolerate extubation. The catheterization documented progressive aortic stenosis (gradient of 78 mmHg), and marked elevation in diastolic pressures in both ventricles. The intervention produced minimal improvement in the aortic valve (reduction to 55mmHg), despite two larger balloon attempts. No aortic insufficiency was created. She was transferred to the ICU, but was unable to wean from mechanical ventilation. After discussion with her family regarding her severely compromised cardiac and lung function, her family elected not to proceed with resuscitation; when she received an optimized trial of extubation, she was unable to maintain adequate ventilation and died.

Patient 4

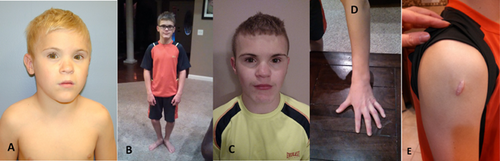

The patient was born SGA 3 days prior to due date to 26 year old nonconsanguineous parents. He had poor feeding, gastroesophageal reflux, and subglottic stenosis. His motor development was mildly delayed and at two years of age bilateral hearing loss was found on evaluation for delayed speech. He was found to be growth hormone deficient and placed on growth hormone at age eight. Since starting growth hormone he has progressed from the 5th centile to the 30th centile for height (at 13 years of age). He had seen genetics at seven years of age for evaluation of dysmorphic craniofacial features (Fig. 4A–C), hypotonia, hearing loss, restricted finger joint movement (Fig. 4D), and short stature which resulted in a normal microarray and Noonan syndrome testing. At nine years of age he underwent choanal stenosis repair. Spirometry demonstrated persistent restrictive lung disease without response to albuterol. He had a diagnostic right deltoid muscle biopsy which showed small striated muscle fibers of minimal size variation. Histologic analysis showed esterase-positive cellularity within the epimysial connective tissue. The biopsy site required several weeks to heal and resulted in a large fibrotic scar (Fig. 4E). He had normal echocardiograms at 6 and 11 years of age. On follow up with genetics, at 11 years of age he was recognized to have findings of Myhre syndrome; SMAD4 targeted testing confirmed a c.1498A > G (p.Ile500Val) mutation. By 13 years of age he had a total of nine sets of myringotomy tubes and continues to have restrictive pulmonary disease but otherwise well, and is attending school full time.

Patient 5

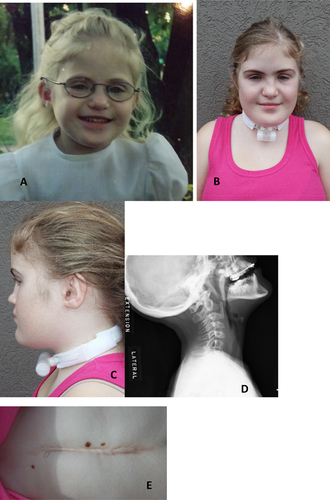

The fifth patient was born SGA at 37 weeks gestation to healthy nonconsanguineous parents (maternal age 25 years; paternal age 28 years) with a noncontributory family history. On clinical genetics evaluation at four years of age she was noted to have dysmorphic craniofacial features (Fig. 5A–C), bilateral hearing loss (right ear primarily conductive; left ear mixed), strabismus, velopharyngeal insufficiency, asthma, gastroesophageal reflux, prior gastric fundoplication, mild periventricular leukomalacia, limited joint extensibility, and speech and gross motor delays. She had normal social development and intelligence. At that time height was 94 cm, (3rd centile), weight was 14.2 kg (10th centile) and head circumference was 50.1 cm (45th centile). She had a flat nasal bridge, a systolic murmur, and limited movement of the joints. Subsequent clinical course was significant for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy at age seven years. At age eight years she underwent a superiorly based pharyngeal flap and was noted to have vocal cord paresis and subglottic stenosis with scarring of the vocal cords. She was found to have fusion of the C6 and C7 vertebral bodies with widening of the C5-C6 disc space (Fig. 5D). She was diagnosed with systemic hypertension and suffered multiple episodes of otitis media and pneumonias with pleural effusion. She had hypogammaglobulinemia with recurrent variable infections which has responded to IVIG treatment.

At 12 years of age she presented with cough and positional dyspnea. Echocardiogram demonstrated a very large pericardial effusion and severe reduction in left ventricular systolic function with shortening fraction of 10%. Ventricular chambers were normal in size but both atria were dilated. Following drainage of her pericardial effusion her ventricular function remained poor with evidence of abnormal diastolic function with an E/A ratio > 3:1. During this evaluation intubation required multiple attempts and special measures. She was transferred to a tertiary care center for consideration of advanced heart failure therapies. She was diuresed and started on inotropic support with recovery of ventricular function within 24 hours. One year later the patient developed diffuse edema and dyspnea. Evaluation at that time demonstrated normal sized ventricles with preserved systolic function, dilated atria, abnormal mitral inflow as noted previously, a small pericardial effusion, and elevated BNP consistent with constrictive or restrictive physiology. As part of her vascular workup for chronic hypertension, she was noted to have a diffusely small descending aorta and focal stenosis of the celiac artery. At 13 years of age, the patient developed progressive sublaryngeal stenosis and a tracheostomy was performed. At followup she was noted to have a shelf of scar tissue with complete soft tissue stenosis of the airway. Both her fundoplication (Fig. 5E) and tracheostomy incisions resulted in a hypertrophic scar.

Normal genetic studies throughout her course included an amniocentesis 46,XX karyotype, 22q11.2 FISH, subtelomere FISH, and microarray analysis (2013). At 14 years of age SMAD4 sequencing showed a c.1499T > C (p.Ile500Thr) mutation.

At 15 years of age the patient continues to have significant issues with severe subglottic stenosis that had progressed to grade IV, resulting in inability to vocalize; evaluation for laryngotracheal reconstruction was in process.

DISCUSSION

Myhre syndrome is caused by apparent gain-of-function mutation in SMAD4 which, to date, appear to be restricted to heterozygous missense changes in Ile500 within the conserved MAD homology 2 domain of exon 11 [Caputo et al., 2012; LeGoff et al., 2012, 2014] in all but three reported patients. In these three patients with a clinical phenotype of Myhre syndrome, an Arg496 change [Caputo et al., 2014; Michot et al., 2014] was instead documented. These patients were of normal stature and did not have cardiac anomalies. While the Arg496 residue is involved in the transcriptional activation of SMAD4 it only results in dysregulation via altered expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which act as a major contributor to extracellular matrix (ECM) stability [Caputo et al., 2014; Piccolo et al., 2014]. In contrast, the more typical Ile500 aberrations affect the MMPs as well as their related inhibitors [Piccolo et al., 2014].

In Myhre syndrome, because of decreased mono-ubiquitination, stability is inferred upon the SMAD4 protein which disrupts TGFβ signaling, resulting in abnormal development of axial and appendicular skeletal structures, skeletal and cardiac muscular development as well as the central nervous system [Caputo, 2012; Le Goff, 2014]. The role of the SMADs has been well established in a spectrum of acquired cardiac diseases, including cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy, aortopathies, atherogenesis and pulmonary artery hypertension. SMAD4, a central cytoplasmic mediator of the TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways, has been shown to have increased expression in patients with cardiac atrial fibrosis [Gramley et al., 2010].

Although there has not been a Myhre syndrome-specific mouse model, there have been other mouse models looking at the role of SMAD4 as it relates to cardiac form and function. A mouse model with cardiac myocyte-specific disrupted SMAD4 developed heart failure secondary to significant cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis [Wang et al., 2005]. Cardiac tissue fibrosis has also been induced in cardiac fibroblasts from a mouse model directly targeting SMAD4, increasing the profibrogenic TGF- β1 activity [Huang et al., 2014]. A keratinocyte-specific SMAD4 knockout mouse has been shown to have a significantly accelerated rate of keratinocyte proliferation and wound contraction [Yang et al., 2012].

We present five previously unpublished patients with Myhre syndrome with documented SMAD4 missense mutations in the isoleucine residue at position 500 (Table I). While all share cardinal features of progressive hearing loss, restricted joint movement, thick skin, and compact habitus, they also demonstrate impressive variability in clinical expression. We are not aware of any prior reports of need for cardiac transplantation in this patient population. While minor cardiac involvement has been reported in many patients with Myhre syndrome the need for and outcome of surgical intervention, has not been thoroughly described. Constrictive pericarditis has been reported in LAPS (Laryngotracheal stenosis, Arthropathy, Prognathism, and Short stature) syndrome, a condition determined to be a phenotypic variant of Myhre syndrome by Lindor et al. in 2012 [Picco et al., 2013; Michot et al., 2014]. In Lindor's series, one patient who underwent pericardectomy for presumed constrictive pericarditis, had persistent restrictive indices on echocardiography suggesting that restrictive cardiomyopathy may have been the underlying disease process as it was in the four patients we describe with cardiomyopathy.

| Patient | Age in years | Cardinal features* | SMAD4 | Sex | Paternal age | Cardio/pulmonary restrictive disease | Newly reported features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 (deceased) | + | I500 T | F | 29 | +/? | Post-transplant (heart) complications |

| 2 | 12 (deceased) | + | I500 T | F | 37 | +/+ | Duodenal atresia, post-transplant (heart and lung) complications |

| 3 | 26 (deceased) | + | I500 V | F | 30 | +/+ | Optic nerve sheath meningioma |

| 4 | 13 (at time of report) | + | I500 V | M | 26 | −/+ | Favorable response to growth hormone |

| 5 | 15 (at time of report) | + | I500 T | F | 28 | +/+ | Hypogammaglobulinemia resolved with IVIG treatment |

- *Hearing loss, typical facial features, compact build, restricted joint movement, thick skin.

Specifically, Myhre syndrome patients undergoing transplantation have not been previously reported and we present two patients who were unable to survive post-transplantation complications. These patients had significant fibrotic scarring of the heart itself and surrounding mediastinal structures from presumed previous tissue damage or instrumentation. Of note, the pericardium itself was noted to be normal in these three patients where the pericardium was inspected intraoperatively or on autopsy. This article highlights a potential deleterious effect of surgery in these patients with abnormal tissue response resulting in impaired wound healing, anastamotic strictures, and adverse myocardial remodeling. Prior concern about wound healing in Myhre syndrome was raised by Lindor et al, noting life-threatening adhesions following hysterectomy in a patient who also had chronic restrictive cardiomyopathy which persisted after pericardectomy [Lindor et al., 2012].

In addition, Myhre syndrome patients are prone to complicated airway management. Post-intubation/tracheal-trauma fibrotic scarring resulting in grade IV stenosis is presumed in Patient 5 and has also been reported in multiple other patients with Myhre syndrome [Oldenburg et al., 2015] and we recommend extraordinary caution with intubation.

The decision to take a patient with Myhre syndrome to surgery of any kind should include a discussion of an apparently abnormal wound healing process, abnormal adhesions and fibrosis that could impact overall success and both short- and long-term morbidity and mortality. The potential for current and future difficult airway management should also be reviewed. For all Myhre syndrome patients, serial echocardiograms should be performed to detect progressive valvar and myocardial disease. We recommend an echocardiogram at the time of diagnosis of Myhre syndrome and at a minimum of every two years thereafter or if symptoms arise. In addition, prompt referral for pulmonary evaluation with functional testing should be performed if symptoms suggest compromise, due to the increased risk for restrictive pulmonary insufficiency. Patients with Myhre syndrome should be closely monitored post-operatively for abnormal fibrotic wound healing and elective surgical procedures should be avoided if at all possible given the attendant risks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to sincerely thank these five patients and their families for their eager participation, support, and advocacy. We would also like to thank Dr. Angela Lin from the Harvard Medical School in Boston, MA for her insight.