Two further cases of spondyloenchondrodysplasia (SPENCD) with immune dysregulation†

How to cite this article: Navarro V, Scott C, Briggs TA, Barete S, Frances C, Lebon P, Maisonobe T, Rice GI, Wouters CH, Crow YJ. 2008. Two further cases of spondyloenchondrodysplasia (SPENCD) with immune dysregulation. Am J Med Genet Part A.

Abstract

Although the diagnosis of spondyloenchondrodysplasia (SPENCD) can only be made in the presence of characteristic metaphyseal and vertebral lesions, a recent report has highlighted the pleiotropic manifestations of this disorder which include significant neurological involvement and variable immune dysfunction. Here we present two patients, one of whom was born to consanguineous parents, further illustrating the remarkable clinical spectrum of this disease. Although both patients demonstrated intracranial calcification, they were discordant for the presence of mental retardation, spasticity and white matter abnormalities. And whilst one patient had features consistent with diagnoses of Sjögren syndrome, polymyositis, hypothyroidism and severe scleroderma, the other patient had clinical manifestations and an autoantibody profile of systemic lupus erythematosus. These cases further illustrate the association of SPENCD with immune dysregulation and highlight the differential diagnosis with Aicardi–Goutières syndrome and other disorders associated with the presence of intracranial calcification. Undoubtedly, identification of the underlying molecular and pathological basis of SPENCD will provide important insights into immune and skeletal regulation. © 2008 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Spondyloenchondrodysplasia (SPENCD: OMIM 271550) is a rare skeletal dysplasia characterized by radiolucent metaphyseal and vertebral lesions that represent islands of chondroid tissue within bone [Schorr et al., 1976]. Fascinatingly, the phenotype can be associated with variable features suggestive of immune dysfunction (including autoimmune thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, thyroiditis and lupus), as well as significant neurological involvement (mental retardation, spasticity and intracranial calcification) [Renella et al., 2006]. Evidence for both autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance exists. The underlying molecular and pathological basis of the disease is unknown.

We present two patients, a female born to a nonconsanguineous couple and a male born to consanguineous parents, with features of SPENCD including metaphyseal changes, platyspondyly and short stature. The female demonstrated moderate mental retardation, seizures and basal ganglia calcification with patchy signal changes in the deep white matter. Of particular note, she developed Sjögren syndrome, polymyositis, hypothyroidism, severe scleroderma/acrocyanosis and a multifocal neuropathy. The combination of acrocyanosis, intracranial calcification, white matter disease and immune dysregulation suggested a pathogenic overlap with Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS). However, screening of AGS1-4 was normal. The male child developed significant lower limb spasticity with intracranial calcification, a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and features consistent with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). He was of normal intellect. These cases further illustrate the association of SPENCD with immune dysregulation.

CLINICAL REPORTS

Patient 1

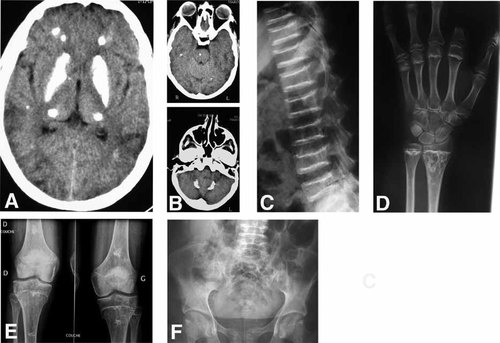

This female was born at term to nonconsanguineous French parents by vaginal delivery weighing 2.9 kg (10th centile). Her perinatal course was unremarkable and her early development was reported to be normal. She walked at age 14 months. At 3 years of age she experienced three febrile seizures. Assessment at that time revealed moderate mental retardation without focal neurological signs. Dense intracranial calcification, particularly involving the basal ganglia, was reported on CT. Although these early films are unavailable, similar changes were observed at age 22 years (Fig. 1A,B). She was short (−1 SD at 1 year, −4 SD at 7 years; measures in cm not recorded) and she had very blond, sparse hair. A skeletal survey demonstrated platyspondyly (Fig. 1C), metaphyseal changes (Fig. 1D,E) and possible iliac crest irregularities (Fig. 1F) consistent with SPENCD. A TORCH screen was negative. Growth hormone, IGF1 and PTH levels were all within normal limits, and a karyotype was normal.

Patient 1: (A,B) Cranial CT at 22 years of age demonstrating dense bilateral calcification of the basal ganglia and smaller deposits in the thalami, cerebral and cerebellar white matter, and pons. C: Lateral spine radiograph at 21 years of age showing flattening and irregularities of the end plates of the vertebral bodies. D: X-rays of the hands at age 22 years. Note the wavy irregularity of the metaphyses and the drop-like enchondromatous lesions in the distal ulna and radius. These images were obtained after amputation of the second finger (see Fig. 2). X-rays of the knees and pelvis taken at 22 years show changes extending from the metaphyses to the diaphyses of the proximal fibular and tibia and distal femur (E) and possible irregularities of the iliac crests (F).

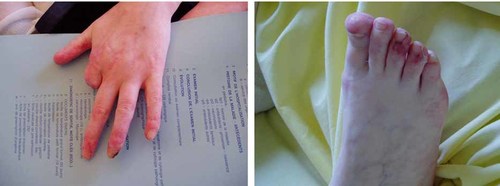

She remained stable until age 14 years when she developed acrocyanotic changes in the hands and feet (Fig. 2). Within 3 years her condition progressed to produce necrosis at the digital extremities. Capillaroscopy showed edema and sludging. Despite regular iloprost infusions, steroids and azathioprine, she developed further necrosis with osteitis requiring amputation of the left index finger.

Patient 1: Sclerodermatous/acrocyanotic changes of the hands and feet. Amputation of the second finger was necessary secondary to necrosis and osteitis. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

At age 17 years she was recognized to have unexplained arterial hypertension which necessitated triple therapy. Renal arteriogram was normal and investigations for hyperaldosteronism and phaechromocytoma were negative.

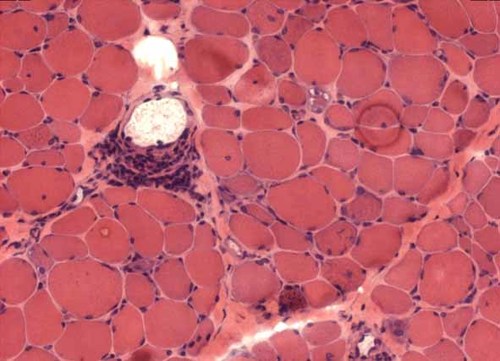

At 18 years of age she began to experience myalgia. Initial muscle biopsy revealed fibro-muscular necrosis without mitochondrial changes, and a repeat biopsy 2 years later showed a chronic, active myositis with necrosis of the muscle fibers and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates (Fig. 3). Electromyography, muscle MRI and muscle enzyme studies (CK 1488 UI/l; normal <170) confirmed a diagnosis of polymyositis. She was treated with oral cortisone and azathioprine, which resulted in a progressive clinical and biochemical improvement. In view of reported xerostomia, a salivary gland biopsy was undertaken and demonstrated chronic sialadenitis (grade IV Chisholm) with polyclonal B cell and lymphocytic infiltrates consistent with a diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. At this time, because of swallowing difficulties, she also underwent manometry which revealed esophageal achalasia. Two years later she experienced bouts of severe abdominal pain and diarrhea that were considered related to intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

Patient 1: Frozen transverse section of muscle biopsy (deltoid: 540× magnification) stained with hematoxylin–eosin showing inflammatory perivascular infiltrates with necrotic and regenerating fibers. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

At age 21 years, whilst taking steroids and immunosuppressant therapy, she developed a painful multifocal neuropathy with features of axonal loss of both motor and sensory nerves and minimal inflammatory lymphocytic infiltration of epineural veinules on biopsy. No necrosis or vasculitis was seen. At this same age, in the context of a treated sinusitits, she also presented in status epilepticus complicated by unexplained circulatory failure requiring inotropic support. CSF examination, including interferon-alpha, was normal. A serum interferon-alpha assay was also normal. A second episode of status the following year was associated with a fever of unknown origin. CSF evaluation showed a minor elevation of lactate with a normal cell count and interferon-alpha titer. Of uncertain significance, a serum sample demonstrated an interferon alpha level of 25 IU/L (normal <2 IU/L). Mutation analysis of AGS1-4 was negative. Cranial MRI showed patchy periventricular white matter changes (Fig. 4A), and cerebral angiography demonstrated an aneurysm at the bifurcation of the right middle cerebral artery (Fig. 4B). EEG was normal.

Patient 1: (A) Cranial MRI at 22 years of age demonstrating patchy periventricular high signal extending out to superficial white matter in places. B: Cerebral angiography demonstrating an aneurysm at the bifurcation of the right middle cerebral artery.

She was diagnosed with hypothyroidism at age 22 years and also experienced an episode of unexplained acute pancreatitis around this time. Autoantibody testing revealed a moderately positive ANA (1/320) with nuclear dots and diffuse cytoplasmic fluorescence, but was otherwise negative (notably for nuclear antigens and anti-thyroid antibodies). Additionally, following a decrease in her visual acuity at this same age, she was shown to have features of chorioretinal inflammation on angiography.

At 23 years of age she weighed 33 kg (13 kg <5th centile) and was 1.35 m tall (17 cm <5th centile). She was non-dysmorphic and demonstrates no focal neurological signs. She lived alone and was able to read and write, but she functioned at the level of a primary school child and required the regular input of her parents. Her mother, 1.62 m tall (25th centile), was asymptomatic. Her father, 1.55 m tall (4 cm <0.4th centile), committed suicide at the age of 38 years. Her brother, of normal stature, was reported to experience Raynaud phenomena of the hands in the cold and is currently under investigation for unexplained arterial hypertension. No other members of the family have undergone radiological examination.

Patient 2

This male child was born to first cousin Turkish parents at 39 weeks gestation weighing 2.75 kg. His father had schizophrenia and his mother gave a description of a possible vasculitic skin rash about which no further information was available. Parental heights were not recorded. His developmental milestones were within normal limits, saying his first words at the age of 13 months and walking independently at 18 months of age.

He presented at the age of  years with walking difficulties, frequent falls and a skin rash in the absence of fever or systemic illness. On examination his height was 87 cm (3rd centile), weight 13.4 kg (25th centile) and head circumference 48.5 cm (between 3rd and 25th centiles). Neurological examination revealed increased tone and hyper-reflexia in his lower limbs although he was not demonstrably weak. The rest of the neurological review was normal. Systematic examination identified palpable purpura and petechiae on the lower limbs.

years with walking difficulties, frequent falls and a skin rash in the absence of fever or systemic illness. On examination his height was 87 cm (3rd centile), weight 13.4 kg (25th centile) and head circumference 48.5 cm (between 3rd and 25th centiles). Neurological examination revealed increased tone and hyper-reflexia in his lower limbs although he was not demonstrably weak. The rest of the neurological review was normal. Systematic examination identified palpable purpura and petechiae on the lower limbs.

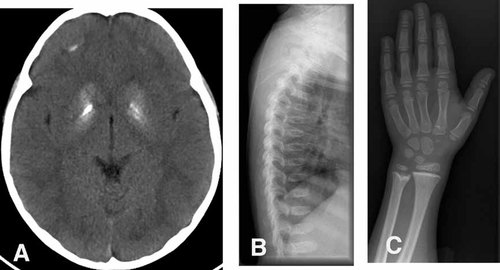

He underwent extensive investigation to identify a cause for his lower limb spasticity. Cranial CT scan revealed two homogenous foci of calcification in the deep white matter of the frontal lobes bilaterally, and calcification of the basal ganglia particularly involving the caudate and putamina (Fig. 5A). MRI of brain and spine and cranial MRA were normal. CSF examination (cell count, glucose, protein, lactate and oligoclonal bands) as well as EMG and ophthalmological examination were non-contributory. There was evidence of past exposure to CMV, EBV and rubella whilst testing for toxoplasmosis, HIV and ASO titers was negative. Urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, sialotransferrins and amino acids were unremarkable. A karyotype was normal as were measures of bone metabolism (calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone). An immunoglobulin screen was within normal limits, and he was negative for lupus anticoagulant, ANA, ANCA and anti-cardiolipin antibody. His ESR was raised (41 mm/hr: normal <15 mm/hr) with a normal CRP. Biopsy of his skin lesions showed a perivascular polymorphonuclear infiltrate without evidence of deposition of complement or immunoglobulin, consistent with a non-specific leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Patient 2: (A) Cranial CT at 2 years 6 months of age demonstrating bilateral calcification of the basal ganglia and smaller deposits in the deep white matter. B: Lateral spine radiograph at 10 years of age showing platyspondyly of the vertebral bodies. C: X-rays of the hands at age 10 years. Note the increased thickening of the metaphyses of the distal ulna and radius.

Following a short course of oral steroid therapy his skin lesions resolved. However, he presented again at age 7 years with a recurrence of his vasculitic rash, together with myalgia and arthralgia in the absence of fevers. There was evidence of a worsening of his lower limb spasticity with the development of contractures at the knees and ankles. His length had fallen to well below the third centile whilst his weight continued to follow the third centile. He remained intellectually normal. CK was not raised but ANA (1:640) and anti-ds DNA (>100 IU/ml) antibodies were positive and there was evidence of complement activation with a C3 (0.54 g/L: normal 0.79–1.52) and raised C3d corrected for patient C3 (8.6%: normal <2.4%). ESR was elevated (68 mm/hr) with a normal CRP. Repeat cranial MRI, and SPECT scanning, were normal.

Therapy with corticosteroids, chloroquine and cyclophosphamide resulted in an improvement of his skin lesions and he was subsequently maintained on azathioprine. Over the following 4 years his disease remained quiescent and his spasticity remained static. At 10 years and 5 months of age his height was 117 cm (13 cm <5th centile) and his weight 26 kg (5th centile). X-rays of his spine and wrists showed platyspondyly (Fig. 5B) and features of a metaphyseal dysplasia (Fig. 5C) consistent with a diagnosis of spondyloenchondrodysplasia. X-ray of the pelvis was reported to show coarse trabeculation of the iliac bones.

DISCUSSION

In consideration of the recognized heterogeneity associated with phenotypes combining enchondromata and platyspondyly [Bhargava et al., 2005], Renella et al. 2006 in their comprehensive review emphasized that SPENCD, as discussed here, can be differentiated from other spondylometaphyseal dysplasias by the presence of specific radiographic features comprising radiolucent spondylar and metaphyseal enchondromal lesions. These lesions are believed to represent persistence of chondroid tissue, a suggestion supported by the results of bone biopsy in one of their patients. Renella et al. also highlighted the pleiotropic extra-osseous manifestations of the condition, sometimes associated with significant variation even within the same family. These features include mental retardation, spasticity and intracranial calcification all of which had been reported previously by other authors. However, they also drew attention to the association of SPENCD with immune dysregulation, ranging from autoimmune disease to, possibly, immunodeficiency [Roifman and Melamed, 2003; Renella et al., 2006]. An additional case showing features of immune dysregulation was recently reported [Kulkarni et al., 2007; Renella and Superti-Furga, 2007] Thus, SPENCD represents another immuno-osseous dysplasia, a group which already includes Schimke type and cartilage hair hypoplasia.

A diagnosis of SPENCD in our cases is supported by short stature and the presence of metaphyseal changes, platyspondyly, and intracranial calcification. Moreover, as in seven of the patients reported by Renella and colleagues, our cases demonstrate a number of features suggestive of immune dysregulation. In patient 1, these include Sjögren syndrome, polymyositis, hypothyroidism, an episode of acute pancreatitis and a possible autoimmune multifocal neuropathy. Of particular prominence was the severe acrocyanosis, experienced from the age of 14 years, with digital necrosis unresponsive to immunosuppressant or vasodilator therapy, and significant gastrointestinal dysfunction with documented esophageal achalasia and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction; features consistent with a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma. Patient 2 meanwhile presented with spasticity and a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, with the subsequent development of an auto-antibody profile consistent with a diagnosis of SLE. The severity and variety of immune features exhibited by patient 1 has not been previously described in other cases of SPENCD, and presumably represents the severe end of the disease spectrum. It is of note that, like our patient 1, patient 4 in the series of Renella et al. 2006 experienced severe and unexplained hypertension.

Frydman et al. 1990 and Tuysuz et al. 2004 described a total of four SPENCD patients with basal ganglia calcification, whilst Renella et al. 2006 reported white matter changes and intracranial calcification in 3 of their 10 cases (although no brain imaging was shown). Our patient 1 demonstrated dense calcification of the basal ganglia which, in combination with the white matter changes and acrocyanosis reminiscent of the chilblain lesions seen in AGS [Crow and Livingston, 2008], prompted consideration of a diagnosis of the latter condition. Although AGS1-4 mutation testing was negative, at least one further AGS-associated gene remains to be defined [Rice et al., 2007a]. Moreover, considering the, albeit infrequent, overlap of AGS with SLE [Aicardi and Goutières, 2000; Dale et al., 2000; De Laet et al., 2005; Rasmussen et al., 2005], and the recent identification of TREX1/AGS1 mutations in SLE [Lee-Kirsch et al., 2007] and familial chilblain lupus [Rice et al., 2007b], we are intrigued by the observation of a raised level of interferon-alpha in the serum of Patient 1. The fact that an earlier sample was normal means that the significance of this finding remains uncertain. The dense intracranial calcification seen in Patient 1 is somewhat reminiscent of the cranial CT appearances observed in CRMCC [Briggs et al., 2008], which can include bony involvement in the form of fractures [Crow et al., 2004]. However, considering other associated features, we think that these phenotypes are different. More generally, we excluded disorders of calcium homeostasis in our patients, and other conditions associated with intracranial calcification such as mitochondrial cytopathies, Cockayne syndrome and Hoyeraal-Hreidarsson syndrome seem unlikely to be relevant from a clinical or pathogenic viewpoint.

Although the skeletal features seen in our patient 1 were obvious and diagnostic of SPENCD, the skeletal features observed in patient 2 were only recognized once a diagnosis of SPENCD was specifically considered and looked for. Renella et al. 2006 highlight the fact that the associated spondylar and metaphyseal lesions can be subtle and non-diagnostic, especially perhaps in the early stages of the disease. Moreover, it is of note that affected individuals can demonstrate a normal height [Renella et al., 2006]. These factors emphasize the importance of considering a diagnosis of SPENCD in patients presenting with early-onset immune dysregulation, even in the absence of clinically obvious skeletal or neurological involvement.

The parents of Patient 2 were consanguineous, consistent with previous reports suggesting autosomal recessive inheritance in SPENCD. However, Renella et al. 2006 have highlighted the possibility of occasional dominant transmission also. In this regard, we note that the father of our Patient 1 was short, and that the otherwise unaffected brother is reported to experience Raynaud phenomena of the hands in the cold, conceivably a forme fruste of the acrocyanosis seen in his sister, and unexplained arterial hypertension.

The pathogenesis of SPENCD is unknown although the acrocyanosis, inflammation of muscular and retinal small vessels and intracerebral aneurysm documented in patient 1 perhaps suggest an underlying vasculopathy. This hypothesis was also tentatively proposed by Renella et al. 2006 in view of the autopsy finding of diffuse arteriosclerosis seen in an 18-year-old male with the disease. Undoubtedly, defining the molecular and pathological basis of SPENCD will provide important insights into immune and skeletal regulation.