Mantle cell lymphoma: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and clinical management

Abstract

Disease Overview

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a non-Hodgkin lymphoma characterized by involvement of the lymph nodes, spleen, blood and bone marrow with a short remission duration to standard therapies and a median overall survival (OS) of 4-5 years.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on lymph node, bone marrow, or tissue morphology of centrocytic lymphocytes, small cell type, or blastoid variant cells. A chromosomal translocation t (11:14) is the molecular hallmark of MCL, resulting in the overexpression of cyclin D1. Cyclin D1 is detected by immunohistochemistry in 98% of cases. The absence of SOX-11 or a low Ki-67 may correlate with a more indolent form of MCL. The differential diagnosis of MCL includes small lymphocytic lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, and follicular lymphoma.

Risk Stratification

The MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) is the prognostic model most often used and incorporates ECOG performance status, age, leukocyte count, and lactic dehydrogenase. A modification of the MIPI also adds the Ki-67 proliferative index if available. The median OS for the low-risk group was not reached (5-year OS of 60%). The median OS for the intermediate risk group was 51 months and 29 months for the high risk group.

Risk-Adapted Therapy

For selected indolent, low MIPI MCL patients, initial observation may be appropriate therapy. For younger patients with intermediate or high risk MIPI MCL, aggressive therapy with a cytotoxic

Regimen followed by autologous stem cell transplantation should be considered. Rituximab maintenance after autologous stem cell transplantation has also improved the progression-free and overall survival. For older symptomatic MCL patients with intermediate or high risk MIPI, combination chemotherapy with R-CHOP, R-Bendamustine, or a clinical trial should be considered. In addition, rituximab maintenance therapy may prolong the progression-free survival. At the time of relapse, agents directed at activated pathways in MCL cells such as bortezomib (NFkB inhibitor), lenalidamide (anti-angiogenesis) and Ibruitinib (Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase [BTK] inhibitor) have demonstrated excellent clinical activity in MCL patients. Autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplantation can also be considered in young patients. Clinical trials with novel agents are always a consideration for MCL patients.

1 DISEASE OVERVIEW

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) was originally identified in the Kiel classification as a “centrocytic lymphoma”.1 This type of lymphoma was termed a lymphocytic lymphoma of intermediate differentiation by Berard.2 A distinct subtype of MCL was characterized by atypical small lymphoid cells with wide mantles around benign germinal centers and was called a mantle zone lymphoma.3 With the advent of the revised European-American (REAL) and the later World Health Organization (WHO) classifications, MCL was made a distinct lymphoma subtype and was termed an aggressive lymphoma.4, 5 MCL represents about 4% of all lymphomas in the US and 7–9% in Europe.6

Patients with MCL have a median age in their 60s and have a striking male predominance (2:1). Patients generally have stage III/IV disease and present with extensive lymphadenopathy, blood and bone marrow involvement, and splenomegaly.7 Eighty percent of the patients with the mantle zone variant have splenomegaly which may be massive. The MCL patients can present with pancytopenia or a leukemic presentation with extensive leukocytosis.8 Some degree of peripheral blood involvement can be detected in most cases by flow cytometry.9 Other extranodal sites include the gastrointestinal tract either in the stomach or colon, liver, or in Waldeyer's ring.10 Some patients have sheets of lymphomatous polyps of the large bowel, lymphomatous polyposis, which sometimes leads to the diagnosis of MCL.11 If random blind biopsies are done of normal appearing mucosa of the colon in patients who have been diagnosed with MCL in other locations, a large percentage are positive for MCL involvement.11 Other extranodal sites for MCL involvement include the skin, lacrimal glands, and central nervous system.10

2 DIAGNOSIS

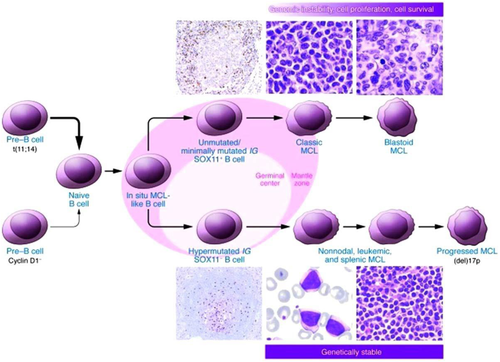

The diagnosis is made on a biopsy of a lymph node, tissue, bone marrow or blood phenotype which shows the typical morphology of mono-morphic small to medium sized lymphoid cells with irregular nuclear contours.5 Four cytologic variants of MCL are recognized, including the Division of Hematology/Oncology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska small cell variant, mantle zone variant; diffuse variant, and the blastic variant.12 Immunophenotyping is commonly used with the MCL cells being CD201, CD51, and positive for Cyclin D1 while being negative for CD10 and Bcl6.5 The hallmark chromosomal translocation t (11:14) (q13; 32) identifies MCL, and can be shown in most cases.13 This translocation leads to the aberrant expression of cyclin D1, which is not typically expressed in normal lymphocytes. A few cyclin D1 negative cases have been identified and appear to have an overexpression of cyclin D2 or D3 instead.14 Overexpression of the transcription factor, SOX11, has been described as a diagnostic marker for MCL with the absence of SOX11 a characteristic of indolent MCL.15 Biologic features such as a high Ki-67 proliferation index or p53 mutations and p16 deletions are closely related to the more aggressive MCL subtypes such as the blastoid variants.16 A model of molecular pathogenesis and progression of MCL was originally proposed by Jares et al.17 This molecular pathogenesis model has recently been updated with the additional information on mutational status and SOX11 status18 (Figure 1).

A proposed model of molecular pathogenesis and progression of MCL (From Jares et al.18).

Staging procedures should include a complete blood count, chemistry profile, a lactic dehydrogenase (LDH), a bone marrow evaluation, with immunophenotyping by flow cytometry of the bone marrow and blood, and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or FDG-PET/CT. The standard uptake values (SUV's) of sites involved with MCL often have low or intermediate values.19 Evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract with endoscopy is warranted if there are clinical symptoms or if a dose intense regimen will be used. Evaluation of the cerebral spinal fluid is not usually done unless there are neurologic symptoms or if the patient has the blastoid variant or a high Ki-67.20 The majority of patients have stage III or IV disease after complete staging is completed.

3 RISK STRATIFICATION

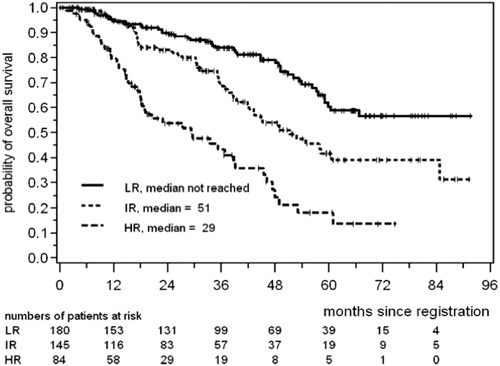

The International Prognostic Index (IPI) was first developed for patients with diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.21 This was used for patients with MCL but was not very discriminatory, particularly for the lower risk patients. More recently the first prognostic index for MCL, the Mantle cell International Prognostic Index (MIPI), was formulated by the European MCL Network.22 The independent prognostic factors for shorter overall survival (OS) from the MIPI were higher age, worse ECOG performance status, higher LDH, and a higher white blood cell count at diagnosis (Table 1). These were calculated as a continuous parameter and three groups emerged: MIPI low-risk with the median OS not reached (5-year OS 60%), MIPI intermediate risk with a median OS of 51 months, and a MIPI high risk group with a median OS of 29 months (Figure 2).22 This index has now been validated by other groups.23

Overall survival for low, intermediate, and high risk MCL according to the MIPI classification (From Hoster et al.22)

| [0.0335 3 age in (years)] 3 age (years) |

|---|

| 1 0.6978 (if ECOG performance status > 1) |

| 1 1.367 3 log 10 (LDH/ULN LDH) |

| 1 0.9393 3 log10(white blood cells per 106 L) |

A simplified modification of the MIPI has also been developed which has high concordance to the original MIPI, but slightly less discriminatory power23 (Table 2). The addition of the Ki-67 proliferation index also provides some additional discriminatory power.23

| Points | Age, years | ECOG PS | LDH/ULN LDH | WBC, 109/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | <50 | 0–1 | <0.67 | <6.700 |

| 1 | 50–59 | – | 0.67–0.99 | 6.700–9.999 |

| 2 | 60–69 | 2–4 | 1.00–1.49 | 214.999 |

| 3 | 70 | – | 1.500 | 15.000 |

For each prognostic factor, 0–3 points are given and the points are summed up to a maximum of 11. Patients with 0–3 points are low risk, patients with 4–5 points are intermediate risk, and patients with 6–11 points are high risk. These risk categories correspond to the categories of the original MIPI.23

Gene expression profiling has been performed on a large series of MCL patients to evaluate a molecular predictor consisting of 20 proliferation associated genes.14 However, a microarray-based technique is not feasible on a wide scale. Therefore, further testing of a minimum number of genes by formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens has been studied.24 This study identified five genes including RAN, MYC, TNFRSF10B, POLE2, and SLC29A2 which were validated by a quantitative reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) based test and predicted survival in 73 patients with MCL. Further validation of these genes and technique is needed before this is used outside a research context.

4 RISK-ADAPTED THERAPY

MCL is responsive to a variety of initial therapies, but relatively short-term remissions are achieved with conventional chemotherapy regimens. The median duration of remission in most previous trials was 1.5–3 years and the median OS was 3–6 years with standard chemotherapy. However, there is a wide variation in outcomes with some patients having a very aggressive presentation and succumbing to their disease in a short period of time, while other patients at the opposite end of the spectrum have a very indolent clinical course. Due to the rarity of MCL, most trials have not been large randomized trials and much of the available information is based on smaller phase II trials with historical controls.

4.1 Initial management of asymptomatic low MIPI or elderly MCL patients

Given the unfavorable prognosis and the fact that standard therapy does not appear to cure patients with MCL, a “watch and wait” strategy for patients with asymptomatic, low MIPI or elderly MCL patients should be considered. This strategy would be similar to that used for asymptomatic patients with follicular or other indolent lymphomas. In a study from Weill-Cornell Medical Center, 97 patients with MCL were evaluated.25 Of the 97, 31 (32%) were observed at the time of initial evaluation. These MCL patients were 46% low-MIPI index as compared to 32% low-MIPI in the patients who received initial treatment. The median time to treatment for the observation group was 12 months (range 4–128 months).25 When this observational patient group needed treatment, the majority received cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, oncovin, and prednisone (CHOP)—like treatment (55%), with some patients receiving rituximab monotherapy (13%), and at the time of publication five patients had never received any therapy.25

When the asymptomatic elderly MCL patient population does become symptomatic and requires therapy, a number of options are available for treatment. Probably the most commonly used regimen in the past has been an anthracycline-based therapy such as CHOP.26 Rituximab monotherapy has some modest activity in MCL.27 Over the last decade, rituximab has been added to the drugs in CHOP (R-CHOP) and tested in MCL. The first report of R-CHOP for the treatment of MCL was in 40 previously untreated patients and yielded an overall response rate (ORR) of 96%, including a complete response (CR) of 48%.28 Despite 36% of the patients having a molecular CR, there was no difference in the median progression-free survival (PFS) between the patients who achieved a molecular CR (16.5 months) and those who did not (18.8 months).28 There were similar results from a randomized study in the German lymphoma study group which compared front-line CHOP to R-CHOP. In this study, the addition of rituximab to CHOP improved the ORR (94% vs. 75%, P = .0054) and the CR rate (34% vs. 7%, P = 0.00024).29 However, this did not translate into significant improvements in PFS or OS in this study.29

Some clinical studies are testing agents used in relapsed MCL in combinations in the front-line setting such as R-CHOP 1 Bortezomib.30 A large phase III trial of R-CHOP vs. bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) demonstrated a 59% improvement in PFS (median 14.4 mo. vs. 24.7 mo.; P < .001) the median OS was 56.3% vs. not reached (hazard ratio 0.80).30 This may be an option in patients who are not eligible for transplant and do not have pre-existing peripheral neuropathy.

Purine analogues have also been used for the treatment of MCL in the older patient population. Single agent fludarabine demonstrated an ORR < 40%; however, when combined with cyclophosphamide and rit-uximab the response rate is closer to 60%.31 More recently, a large randomized trial done in Germany demonstrated that R-CHOP was superior to R-FC in the older MCL patient population with a 4 year OS of 65% for R-CHOP and 50% for R-FC (P = .0032).32 In addition, a second randomization was done for maintenance either with rituximab or interferon. The arm that produced the best PFS and OS, was R-CHOP followed by rituximab maintenance (MR) with a 4-year OS of 87%.32 This is the first large randomized trial which demonstrated a benefit for MR in PFS for patients with MCL.

Another agent that has been tested in patients with MCL which demonstrated good activity is Bendamustine. A randomized trial done in Europe compared R-CHOP to R-Bendamustine in a number of different lymphomas.33 In this trial, the patients with MCL had a similar ORR (89% for BR and 95% for R-CHOP). The BR regimen was associated with a lower progression rate 42% vs. 63% for the R-CHOP arm.33 In addition, the hematologic toxicity and alopecia were less in the R-Bendamustine arm.33 A second study evaluating R-CHOP vs. R-Bendamustine did not demonstrate a superior outcome for the R-Bendamustine, but did demonstrate an equivalent outcome.34

Recommendations: Asymptomatic elderly or low-MIPI patients can be observed without any therapy. When the patients become symptomatic, first line therapy choices include R-Bendamustine, RCHOP(+/- rituximab maintenance), or a clinical trial.

4.2 Initial management of a young symptomatic patient

Several studies have suggested that aggressive therapies in younger patients with MCL may improve the outcomes. One of the first studies to evaluate this was the European MCL Network study where responding patients under age 65 years were randomized after induction therapy to receive either myeloablative radio-chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) or maintenance interferon.36 In this study, the patients in the ASCT arm had an improved PFS over those in the interferon arm.36 Several other single arm and retrospective studies have suggested patients receiving an induction regimen that contains high-dose cytarabine, such as hyperfractioned cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone alternating with high-dose cytarabine and methotrexate (Hyper-CVAD 6 rituximab) experience improved survival.37

The addition to rituximab to 6–8 cycles of HyperCVAD alternating with high dose cytarabine and methotrexate yielded a CR rate of 87% and had a 7-year failure-free survival rate of 52% and OS of 68%.37 This regimen was tested in a multicenter trial and was found to have a similar ORR of 88% and CR rate of 58%; however, there was grade IV hematologic toxicity in 87% of the patients making this regimen difficult to give in some community settings.38 It was also suggested in a retrospective study that patients receiving R-HyperCVAD as an induction with auto ASCT in CR1 had an improved outcome as compared to R-CHOP.39 However a further analysis of a separate cohort of MCL patients demonstrated that when corrected for the MIPI, the outcomes may be similar.40

Since the R-HyperCVAD alternating with methotrexate/cytarabine is difficult to administer, modifications which drop the methotrexate portion41 or drop both the methotrexate and cytarabine have been tested.42 In the study from Geisler et al.,41 160 younger MCL patients received rituximab 1 maxi-CHOP, alternating with rituximab 1 cytarabine. Responders received high-dose chemotherapy with ASCT. The 6-year PFS was 66% and the OS was 70%. Compared to a historical control without the cytarabine, the results were much improved with the regimen as outlined.41 In a small pilot trial in an older population, the rituximab–Hyper CVAD regimen without the methotrexate or cytarabine, but with maintenance rituximab demonstrated an ORR of 77% and a median PFS of 37 months.42 Another approach has been for patients to receive R-CHOP 3 three cycles, then Rituximab, cisplatin, cytarabine, dexamethasone (R-DHAP) 3 3, followed by high dose chemotherapy and ASCT.43 This study also demonstrated an excellent 5-year OS of 75%.43

Recommendations: For young symptomatic patients with MCL, considerations include R-HyperCVAD with high-dose cytarabine (6Methotrexate) or a modified regimen such as the Nordic regimen, followed by ASCT in CR1 for selected patients. For patients who are not candidates for standard R-HyperCVADwithhighdosecytarabine/methotrexate,possiblealternatives include R-CHOP, R-CHOP alternating with R-DHAP, or R-Bendamustine. If possible, ASCT in CR1 should still be considered for these patients as well as post-transplant maintenance rituximab.

4.3 Management of relapse/refractory MCL

For patients with relapsed but asymptomatic MCL, further “watch and wait” may be possible as there are a percentage of patients with indolent MCL who may not need therapy for months or years. Once the patient becomes symptomatic many options are considerations. The Bendamustine rituximab (BR) regimen has also been tested in relapsed MCL patients. A phase II study of BR in 63 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL demonstrated an ORR or 90% with a CR of 60% and a median PFS of 30 months.46 The addition of cytarabine to the BR regimen (R-BAC) demonstrated a high ORR of 80% and a CR rate of 70% in relapsed/refractory MCL patients. However, there was significant cytopenias with this regimen.47

Since many standard lymphoma salvage regimens have limited activity in MCL, novel treatment approaches based on targeting known signaling pathways have been tested. The first such agent to be tested as a proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib. As a monotherapy, bortezomib has demonstrated ORRs in the 30–40% range.48 In a large phase II study of 141 evaluable MCL patients treated with bortezomib, there was an ORR of 33% with a CR rate of 8%.49 With further follow up, the phase II study of bortezomib demonstrated a median time to progression of 6.7 months and a median OS of 23.5 months.50 Bortezomib has also been combined with other agents such as Bendamustine and rituximab in the BVR regimen which also had excellent activity. In patients with MCL the ORR rate for the BVR regimen was 71%.51

The PI3Kinase/Akt/mTOR pathway is implicated in the pathogene-sis of MCL.52 Based upon this information the mTOR inhibitor, temsirolimus was tested in a phase II study of patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. In this study, temsirolimus demonstrated moderate activity with an ORR of 44%.53 In a phase III study of 162 relapsed/refractory patients with MCL, high doses of temsirolimus (175 mg/75 mg) resulted in an ORR of 22% and a PFS of 4.8 months.54 Other mTOR inhibitors, such as everolimus, have also demonstrated activity in MCL.55

The immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide has also shown prom-ising activity against MCL. In a phase II study, Zinzani et al.56 reported an ORR of 41% in 39 MCL patients treated with lenalidomide. The larger EMERGE trial tested single agent lenalidomide in 134 patients with relapsed MCL. The ORR was 28% with a 7.5% CR rate.57 There studies led to the FDA approval of lenalidomide for patients with relapsed MCL who had failed bortezomib. Lenalidomide has also been combined with rituximab with promising results. In a study by Wang et al.,58 52 patients with recurrent MCL were treated with lenalidamide and rituximab for recurrent disease. In this study, the ORR was 58% and the CR rate was 33% with the combination being well tolerated.

Recently, brutons tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor (Ibruitinib) was FDA approved for patients with relapsed MCL. In a study of 111 MCL patients, the BTK inhibitor was reported to have a 68% ORR and a CR rate of 21%, with no differences between bortezomib na€ıve and patients who had relapsed after receiving bortezomib.59 PI3Kinase inhibitor (GS-1101, Idelalisib) which targets the B-cell receptor pathways has demonstrated a 48% ORR in a study of 38 relapsed MCL patients.60

There is not much data available for standard involved field irradiation in MCL. However, there is data with the use of radioimmunotherapy (RIT) with Yttrium90—Ibritumomab Tiuxetan in patients with relapsed MCL demonstrating an ORR of 31%.61 When RIT is used to consolidate after immunochemotherapy, it resulted in improvement of the percentages of responses compared with historical controls.62

Recommendations: My first choice for a relapsed MCL patient would be ibrutinib. bendamustine/rituximab is an option in patients who have not previously received bendamustine. Other options would include rituximab alone, a bortezomib containing regimen, lenalidamide, or a clinical trial. If the patient is a candidate for stem cell transplantation, consideration for an autologous transplant if there was a long first remission or a reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplant should be given.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Nothing to report.