Diagnosis of necrotic and non-necrotic small bowel strangulation: The importance of intestinal congestion

Abstract

Background

Despite the prevalence of laparoscopic techniques in abdominal surgeries today, bowel obstruction remains a potentially serious complication. Small bowel strangulation (SBS), in particular, is a critical condition that can lead to patient mortality. However, the prognosis for SBS is favorable if surgery is performed before the onset of necrosis. Non-necrotic SBS is a reversible condition in which blood flow can be restored by relieving the strangulation. The purpose of this study was to identify sensitive and specific contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) findings that are useful for diagnosis of both non-necrotic and necrotic SBS.

Methods

We included patients diagnosed with SBS and simple bowel obstruction (SBO) who underwent contrast-enhanced CT followed by surgery from 2006 to 2023. Two gastrointestinal surgeons independently assessed the images retrospectively.

Results

Eighty SBO and 141 SBS patients were included. Eighty-seven had non-necrotic SBS and 54 had necrotic SBS. Mesenteric edema was most frequently observed in both necrotic and non-necrotic SBS cases followed by abnormal bowel wall thickening. These two findings were observed significantly less frequently in SBO. Bowel hypo-enhancement is identified in only about half of the non-necrotic SBS cases, and it was detected at significantly higher rates in necrotic SBS compared to non-necrotic.

Conclusion

Mesenteric edema and abnormal bowel wall thickening are sensitive and specific signs of both non-necrotic and necrotic SBS. These two findings indicate mesenteric and bowel congestion. Detecting intestinal congestion can lead to an accurate diagnosis of SBS, particularly in case of non-necrotic SBS, where bowel hypo-enhancement may sometimes be absent.

1 INTRODUCTION

Despite the prevalence of laparoscopic techniques in abdominal surgeries today, bowel obstruction remains a potentially serious complication. Small bowel strangulation (SBS), defined as small bowel obstruction associated with intestinal ischemia caused by strangulation of mesenteric vessels, occurs in approximately 10% of patients with small bowel obstruction (range, 5%–42%), and the mortality rate ranges from 20% to 40%.1, 2 The importance of differentiating SBS from simple bowel obstruction (SBO) is highlighted by their differing mortality rate, which is approximately 10 times higher in SBS than SBO.3 SBS requires immediate surgery to release the strangulation of the small bowel and mesenterium, and a delay in diagnosis can increase the risks of complications and mortality.4 Moreover, the mortality rate escalates when the bowel becomes necrotic or perforated.5 Accurate and early diagnosis of SBS before bowel necrosis is therefore essential to improve patients' outcomes.6 However, despite decades of experience and numerous studies, the optimal diagnostic procedures have not been established and patients continue to die from SBS.

SBS is typically diagnosed according to the presence of the classic clinical signs of vascular compromise, which include continuous abdominal pain, fever, tachycardia, signs of peritoneal irritation, leukocytosis, hyperamylasemia, and metabolic acidosis. However, leukocytosis and an increased C-reactive protein (CRP) level are not always detected without pan-peritonitis nor sepsis.7 Additionally, most SBS are not accompanied by peritoneal irritation signs.

Enhanced computed tomography (CT), which is used to evaluate blood flow, can facilitate the diagnosis of SBS because the pathology of this disease involves a decrease or cessation of intestinal blood flow. Several CT findings indicating SBS such as the presence of a blind loop of small bowel, bowel hypo-enhancement, the mesenteric “whirl” sign, and the “beak” sign are known. Among these CT findings, bowel hypo-enhancement is considered the most reliable.7 However, we often encounter patients with SBS in whom bowel hypo-enhancement is not detected on CT. Additionally, the sensitivity of these CT signs of SBS is low (42%–67%).2, 7-10

Understanding why bowel hypo-enhancement is not often detected in patients with SBS can be the key to accurate and early diagnosis of SBS before the bowel becomes necrotic. We divided patients into those with necrotic and non-necrotic SBS in an effort to elucidate why some patients do not show bowel hypo-enhancement. In the present observational study including patients with SBO, non-necrotic SBS, or necrotic SBS who underwent contrast-enhanced CT before surgery, we paid special attention to contrast-enhanced CT findings of non-necrotic SBS. We believe that precise analysis of non-necrotic SBS, which involves incomplete interruption of blood flow, may help to achieve early and accurate diagnosis of SBS.

2 METHODS

2.1 Objectives and definitions

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local institutional review board (28-01-705). We included patients who underwent surgery from January 2006 to December 2023. We included patients with SBS caused by an internal hernia or adhesion and excluded those with an external hernia (e.g., inguinal or abdominal wall hernia) because the diagnosis is straightforward and does not require CT.

The specific inclusion criteria for this study were (1) a diagnosis of SBO or SBS at the time of laparotomy, (2) availability of contrast-enhanced CT images at the initial visit during which the CT scan was performed within 12 h of surgery for patients with SBS or within 48 h of surgery for patients with SBO, and (3) surgery with or without bowel resection. The exclusion criteria were (1) an inguinal or abdominal wall hernia and (2) obstruction caused by malignancy.

All patients were scanned using multidetector computed tomography (MDCT). However, the CT model used varied depending on when the imaging was performed because this study included patients treated between 2006 to 2023. A contrast medium (2 mL/kg) was injected intravenously at a rate of 3 mL/s. Scanning was performed from the diaphragm to the pubis, with an arterial phase scan conducted 30 s after injection and a slice thickness of 5 mm. For patients whose CT was taken after 2015, a portal venous phase scan was also conducted 80 s after injection.

Necrotic SBS was defined as a purple or black discoloration of the necrotic intestine that required surgical resection with pathological confirmation of massive necrosis. Non-necrotic SBS was defined as a congested intestine caused by strangulation of mesenteric vessels in which ischemic damage was limited and did not require surgical resection or in which massive necrosis was not detected in the resected intestine.

2.2 Evaluation of findings

The CT findings were independently reviewed in random order by two surgeons, each with sufficient knowledge of CT findings of SBS and SBO. The evaluators were unaware of a patient's diagnosis (i.e., SBO, non-necrotic SBS, or necrotic SBS). The final judgment was based on a consensus among the two physicians.

We evaluated two findings that indicated a structural aberration (beak sign and angiectopia of mesenteric vessels), five findings that indicated a blood flow aberration (abnormal bowel wall thickening, high density of the bowel wall on plain CT, mesenteric edema [dirty mesenteric fat sign], disappearance of Kerckring folds, and hypo-enhancement of the bowel wall on contrast-enhanced CT images), and four nonspecific findings (ascites, hemorrhagic ascites, bowel emphysema, and portal venous gas).

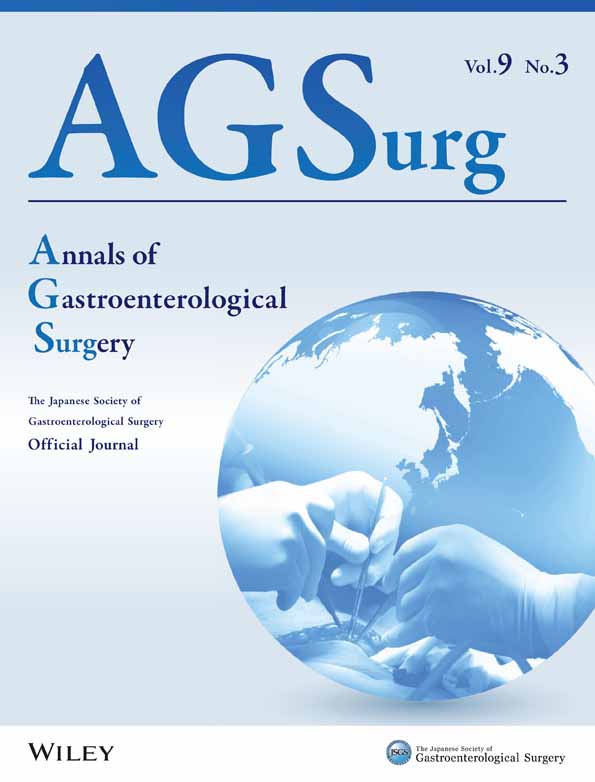

Technical terms are defined as follows. The beak sign, which refers to an abrupt change in caliber at transition points, is characterized by tapering of the intestine similar to a bird's beak (Figure 1A). Angiectopia of mesenteric vessels is indicated by a U- or C-shaped whirl sign (i.e., a swirl of mesenteric soft tissue and fat around the affected loop) (Figure 1B). The whirl sign was originally observed in a patient with intestinal malrotation.11 However, this sign appears when the bowel and mesentery are twisted, and it signifies rotation of the small bowel.

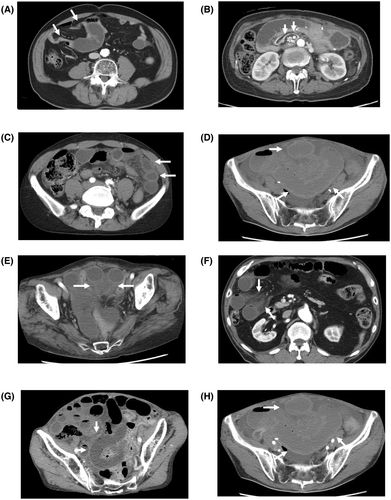

Abnormal bowel wall thickening is defined as thickening of >3 mm (Figure 1C).7, 12, 13 High density of the bowel wall on plain CT, which refers to high density on pre-contrast CT, is caused by hemorrhage or congestion (Figure 1D). Mesenteric edema is an increase in the mesenteric CT value (Figure 1E,F). The disappearance of Kerckring folds refers to a >10-cm length of intestine without Kerckring folds. Strong edema or mucosal necrosis induces the disappearance of Kerckring folds. We excluded patients with intestinal dilation of >5 cm and the disappearance of Kerckring folds with obvious bowel enhancement because these finding are caused by dilatation, not by disturbance of blood flow (Figure 1G). Hypo-enhancement of the bowel wall was defined as the bowel wall without attenuation that was higher on contrast-enhanced than unenhanced images (Figure 1H).12 In patients who underwent surgery after 2015, imaging is conducted during the early contrast phase and the portal vein phase. In some cases, minimal or no contrast effect is observed in the early contrast phase (Figure 2A), but contrast enhancement is evident in the portal vein phase (Figure 2B). We interpret this phenomenon as a delayed enhancement effect, attributable to impaired venous return. In this study, we considered this delayed enhancement effect as hypo-enhancement of the bowel wall. Hemorrhagic ascites was defined as a CT value of >20 Hounsfield units at the bottom of the collected fluid.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney test was conducted to compare age, white blood cell (WBC) count, CRP level, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level, frequency of complications after surgery, mortality, and days of postoperative hospitalization. Sex and the frequencies of imaging findings were analyzed using the chi-squared test. The frequencies of imaging findings were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses using SPSS version 22.0 software (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patients

During the study period, 161 patients with SBO and 183 patients with SBS underwent surgery; however, 81 patients with SBO and 42 patients with SBS did not undergo contrast-enhanced CT. Thus, we included 80 patients with SBO and 141 (87 non-necrotic and 54 necrotic) patients with SBS.

3.2 Diagnosis of SBS

The backgrounds and the frequency of each CT finding of the patients with SBO and SBS are shown in Table 1. WBC, CRP, and CPK were all significantly higher in the SBS group, although the difference of those values between SBS and SBO is insufficient to differentiate the two conditions. Patients with SBS had two or more signs indicating structural or blood flow aberrance, and the median number of signs was five. Conversely, the median number of signs was one in patients with SBO. In SBS, mesenteric edema was the most common findings (92%), followed by abnormal bowel wall thickening (85%) and beak sign (74%). Except for two nonspecific findings (bowel emphysema and portal venous gas), the frequencies of the nine findings were significantly higher in patients with SBS than in patients with SBO. In patients with SBO, only two patients (3%) showed both mesenteric edema and abnormal bowel wall thickening. Conversely, 83% patients with non-necrotic SBS and 85% of patients with necrotic SBS showed both mesenteric edema and abnormal bowel wall thickening.

| SBO, N = 80 | SBS, N = 141 | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 66.5 | 74.0 | 0.005 | ||

| Male | 32 (40%) | 59 (42%) | 0.79 | ||

| WBC (/mL) | 8850 | 10 200 | <0.001 | ||

| CRP (mg/mL) | 0.66 | 0.30 | <0.001 | ||

| CPK (U/mL) | 53.5 | 83.0 | <0.001 | ||

| Structural aberrance | |||||

| Beak sign | 18 (23%) | 107 (74%) | 76 | 78 | <0.001 |

| Angiectopia | 15 (19%) | 61 (42%) | 43 | 81 | <0.001 |

| Blood flow aberrance | |||||

| Wall thickening | 22 (28%) | 123 (85%) | 87 | 73 | <0.001 |

| High density | 9 (11%) | 90 (62%) | 64 | 89 | <0.001 |

| Mesenteric edema | 6 (8%) | 134 (92%) | 95 | 93 | <0.001 |

| Kerckring | 4 (5%) | 75 (52%) | 53 | 96 | <0.001 |

| Hypo-enhancement | 0 (0%) | 85 (59%) | 60 | 100 | <0.001 |

| Non-specific findings | |||||

| Ascites | 33 (41%) | 101 (70%) | 72 | 59 | 0.10 |

| Hemorrhagic ascites | 3 (4%) | 42 (29%) | 30 | 96 | <0.001 |

| Bowel emphysema | 0 (0%) | 7 (5%) | 5 | 100 | |

| Portal venous gas | 0 (0%) | 3 (2%) | 2 | 100 |

- Abbreviations: Angiectopia, angiectopia of mesenteric vessels; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; CRP, C reactive protein; flower bouquet, converging vessels to one area (flower bouquet sign); high density, high density of bowel wall on plain computed tomography; hypo-enhancement, hypo-enhancement of bowel wall on contrast-enhanced images; Kerckring, disappearance of Kerckring's folds; RI, remote infection; SBS, small bowel strangulation; SSI, surgical site infection; wall thickening, abnormal bowel wall thickening, WBC, white blood cell.

The specificities of the nine findings were high (73%–100%), whereas the sensitivity of six of the nine findings was low (30%–64%). In terms of the sensitivity, mesenteric edema (95%) was the most reliable sign, followed by abnormal bowel wall thickening (87%). In terms of specificity, hypo-enhancement (100%) was the most reliable sign, followed by disappearance of Kerckring folds and the presence of hemorrhagic ascites (96%).

4 COMPARISON BETWEEN NON-NECROTIC SBS AND NECROTIC SBS

The backgrounds of the patients with SBS are shown in Table 2. The median age of the patients in the necrotic group was higher than that of patients in the non-necrotic group (p < 0.001). There was significant difference in the WBC count between patients with necrotic and non-necrotic SBS. Patients with necrotic SBS had a significantly higher incidence of ileus and a significantly longer hospital stay than patients with non-necrotic SBS.

| Non-necrotic SBS, N = 87 | Necrotic SBS, N = 54 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.0 | 77.5 | <0.001 |

| Male | 43 (49%) | 22 (41%) | 0.31 |

| WBC | 9500 | 11 250 | 0.009 |

| CRP | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.29 |

| CPK | 71 | 108 | 0.08 |

| Complication | |||

| SSI | 6 (7%) | 6 (11%) | 0.38 |

| Abscess | 4 (5%) | 3 (6%) | 0.89 |

| RI | 7 (8%) | 4 (7%) | 0.85 |

| Ileus | 9 (10%) | 21 (39%) | <0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0.70 |

| In-hospital mortality | 1 (1%) | 2 (4%) | 0.67 |

| Hospital stay after surgery (days) | 10.0 | 12.5 | <0.001 |

- Abbreviations: CPK, creatine phosphokinase; CRP, C reactive protein; RI, remote infection; SBS, small bowel strangulation; SSI, surgical site infection; WBC, white blood cell.

The frequency of each CT finding is shown in Table 3. The most frequent finding among patients with non-necrotic SBS was mesenteric edema (94%), followed by abnormal bowel wall thickening (89%) and beak sign (82%). The most frequent finding among patients with necrotic SBS was also mesenteric edema (96%), followed by disappearance of Kerckring folds (87%), abnormal bowel wall thickening (85%) and ascites (85%). Bowel hypo-enhancement was detected in 51% of patients with non-necrotic SBS and 76% of patients with necrotic SBS. Whether contrast images were taken in both phases or one phase had no significant impact on sensitivity of bowel hypo-enhancement. The sensitivity in two-phase imaging was 51% compared to 37% in single-phase imaging for non-necrotic SBS patients, and the sensitivity in two-phase imaging was 80% compared to 74% in single-phase imaging for necrotic SBS patients The median number of positive findings was significantly higher in necrotic than non-necrotic SBS (7 vs. 4, p < 0.001).

| All, N = 141 | Non-necrotic SBS, N = 87 | Necrotic SBS, N = 54 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural aberrance | ||||

| Beak sign | 107 (76%) | 71 (82%) | 36 (67%) | 0.37 |

| Angiectopia | 61 (43%) | 42 (48%) | 19 (35%) | 0.02 |

| Blood flow aberrance | ||||

| Wall thickening | 123 (87%) | 77 (89%) | 46 (85%) | 0.51 |

| High density | 90 (64%) | 48 (55%) | 42 (78%) | 0.03 |

| Mesenteric edema | 134 (95%) | 82 (94%) | 52 (96%) | 0.20 |

| Kerckring | 75 (53%) | 28 (32%) | 47 (87%) | <0.001 |

| Hypo-enhancement | 85 (60%) | 44 (51%) | 41 (76%) | <0.001 |

| Non-specific findings | ||||

| Ascites | 101 (72%) | 55 (63%) | 46 (85%) | <0.001 |

| Hemorrhagic ascites | 42 (30%) | 19 (22%) | 23 (43%) | <0.001 |

| Bowel emphysema | 7 (5%) | 3 (3%) | 4 (7%) | 0.59 |

| Portal venous gas | 3 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0.58 |

- Abbreviations: Angiectopia, angiectopia of mesenteric vessels; flower bouquet, converging vessels to one area (flower bouquet sign); high density, high density of bowel wall on plain computed tomography; hypo-enhancement, hypo-enhancement of bowel wall on contrast-enhanced images; Kerckring, disappearance of Kerckring's folds; wall thickening, abnormal bowel wall thickening.

The frequencies of disappearance of Kerckring folds, bowel hypo-enhancement, ascites, and hemorrhagic ascites were significantly higher in patients with necrotic than non-necrotic SBS. The multivariate analysis, including nine findings because the frequencies of bowel emphysema and portal venous gas were exceptionally low, showed that the disappearance of Kerckring folds and bowel hypo-enhancement were independent risk factors for necrotic SBS (Table 4).

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beak sign | 1.2 | 0.2–6.5 | 0.77 |

| Angiectopia | 0.5 | 0.1–2.9 | 0.47 |

| Flower bouquet | 3.6 | 0.6–20.8 | 0.15 |

| Wall thickening | 1.1 | 0.1–10.8 | 0.96 |

| High density | 0.47 | 0.1–4.1 | 0.50 |

| Mesenteric edema | 0.58 | 0.0–9.8 | 0.71 |

| Kerckring | 15.7 | 2.7–91.3 | 0.002 |

| Hypo-enhancement | 16.1 | 1.8–142.2 | 0.01 |

| Ascites | 6.3 | 0.7–58.5 | 0.11 |

| Hemorrhagic ascites | 5.6 | 0.96–32.4 | 0.056 |

- Note: The multivariate analysis for necrotic and non-necrotic SBS showed that the disappearance of Kerckring folds and bowel hypo-enhancement were independent risk factors for necrotic SBS.

- Abbreviations: Angiectopia, angiectopia of mesenteric vessels; flower bouquet, converging vessels to one area (flower bouquet sign); high density, high density of bowel wall on plain computed tomography; hypo-enhancement, hypo-enhancement of bowel wall on contrast-enhanced images; Kerckring, disappearance of Kerckring's folds; wall thickening, abnormal bowel wall thickening; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

5 DISCUSSION

The present study clearly demonstrated clinical and radiological difference between non-necrotic and necrotic SBS. Clinical experience indicates that SBS requiring bowel resection (necrotic SBS) is more severe compared to cases not requiring such intervention (non-necrotic SBS); however, existing guidelines do not distinguish between these two conditions.14 Notably, the observation that two indicators of congestion—mesenteric edema and abnormal bowel wall thickening—were present in over 90% of both non-necrotic and necrotic SBS cases implies that congestion is a likely primary cause of SBS rather than ischemia. Conversely, bowel hypo-enhancement was more commonly associated with necrotic SBS than with non-necrotic SBS, indicating that severe congestion may progress to ischemia and subsequent bowel necrosis.

Nine of the 11 findings validated in this study were identified at significantly higher rates in SBS compared to SBO. Only bowel hypo-enhancement had a specificity of 100%, and the other findings were not conclusive evidence of SBS. However, the odds ratios for both mesenteric edema and disappearance of Kerckring's folds were high, a finding strongly suggesting SBS. It should be noted that the sensitivity of disappearance of Kerckring's folds is low, particularly in non-necrotic SBS. Therefore, it is not a reliable finding in diagnosing SBS. Few papers have focused on this finding. Considering the odds ratio and specificity, it seems advisable to focus on seven findings (beak sign, abnormal bowel wall thickening, high density of bowel wall, mesenteric edema, disappearance of Kerckring's folds, bowel hypo-enhancement, and hemorrhagic ascites) to diagnose SBS. Kim et al. reported low incidences of abnormal bowel wall thickening and mesenteric edema in SBO, consistent with findings of our study.15

Although both non-necrotic and necrotic SBS require surgery, it would be useful to classify them to understand the pathophysiology of SBS and to make a more accurate diagnosis. In the present study, non-necrotic SBS was associated with a good prognosis, had a significantly lower incidence of postoperative ileus, and had a significantly shorter median duration of postoperative hospitalization. Additionally, non-necrotic SBS may be more difficult to diagnose than necrotic SBS because of the lower number of positive findings compared to necrotic SBS. In previous studies, the detection rates using imaging of SBS ranged from 14.8% to 100%,16, 17 probably because the presence of non-necrotic SBS is decreasing the accuracy of diagnosis.

Mesenteric edema and abnormal bowel wall thickening are sensitive and specific signs of both non-necrotic and necrotic SBS. Additionally, the sensitivity of mesenteric edema and abnormal bowel wall thickening did not differ between the two conditions. Therefore, these two findings help in accurately diagnosing SBS. Published data also reveal a high incidence of mesenteric edema in patients with SBS2, 13, 18, 19; however, the incidence of bowel wall thickening is low (36%–53%).7, 8, 16, 18, 20 Congestion causes abnormal bowel wall thickening, however as necrosis progresses, the bowel wall thins. Therefore, abnormal bowel wall thickening wall may not be identified in cases with advanced necrosis. High mortality rates in previous studies indicates that those studies included many patients with advanced necrosis.

Bowel hypo-enhancement is a highly specific finding for SBS, but it should be noted that the positivity rate in non-necrotic SBS is low. The multivariate analyses revealed that bowel hypo-enhancement was not an independent risk factor for necrotic SBS, however its sensitivity was not so high in non-necrotic SBS. It has been believed that the cause of SBS is arterial blood flow disorder and that bowel hypo-enhancement is the primary finding.20 However, the studies that focused on bowel hypo-enhancement had low sensitivity.7, 9, 12, 13, 16, 20 Recently, Kobayashi et al. also reported low sensitivity of bowel hypo-enhancement in non-necrotic SBS.21 Ohira et al. reported that the arterial phase of dynamic CT can improve detection of bowel hypo-enhancement.22

The present study has several limitations. For example, it was a retrospective study conducted at a single institution and included a small number of patients. However, it included a greater number of patients with SBS than have previous studies. Patients with SBO who did not undergo surgery were not included because we focused on CT just before surgery. There is little drawback to excluding cases where conservative treatment was administered after CT imaging and the patient showed improvement, as there were no findings suggestive of strangulation. The timing of CT scans differed between SBS and SBO cases. In the case of SBO, CT scans were permitted up to 48 hours before surgery, as only a few cases underwent surgery immediately after the scan.

6 CONCLUSION

Mesenteric edema and abnormal bowel wall thickening are sensitive and specific signs of both non-necrotic and necrotic SBS. Therefore, when diagnosing strangulated intestinal obstruction, attention should be paid to these two findings that suggest congestion. Bowel hypo-enhancement is a highly specific finding for SBS; however, it should be noted that the positivity rate in non-necrotic SBS is low.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Takeshi Yamada: Conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; project administration; visualization; writing – review and editing. Yuto Aoki: Conceptualization; data curation; methodology. Akihisa Matsuda: Formal analysis; writing – review and editing. Yasuyuki Yokoyama: Data curation; formal analysis. Goro Takahashi: Data curation; formal analysis. Takuma Iwai: Data curation; formal analysis. Seiichi Shinji: Conceptualization. Hiromichi Sonoda: Conceptualization; data curation. Kay Uehara: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Hiroshi Yoshida: Supervision; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive any grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Kay Uehara is an editorial member of Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the research protocol: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for the local Institutional Review Board of Nippon Medical School (Approval no. 28-01-705).

Informed Consent: N/A.

Registry and the Registration No. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal Studies: N/A.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.