A critical race theory curriculum for emergency medicine learners

Supervising Editor: Teresa Y. Smith, MD, MSEd.

Abstract

Objectives

We set out to develop and implement a critical race theory (CRT) curriculum to address an identified gap in emergency medicine education. Sessions explored concepts of CRT and issues of racism as they relate to the clinical and extraclinical environments.

Methods

We developed a series of five virtual workshop sessions in 2019 that were held over Zoom in June and July 2020 in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eight learners completed the curriculum. Prior to each session, learners were provided presession materials including podcasts, recorded lectures, and readings. Thought-provoking questions were also provided with presession materials to facilitate discussion during sessions. Materials were curated to provide foundational knowledge on CRT and U.S. history as well as local history of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Results

Participants found the curriculum useful, reported increased familiarity with CRT, and were more likely to have an analytic framework for topics of race and racism. Participants also reported that their perspective had been changed after completing the curriculum.

Conclusions

Our curriculum promoted effective engagement with topics of race and racism by learners. Opt-in participation contributed to an engaged cohort and the small cohort size encouraged participation by all learners. Semistructured facilitation allowed participants to guide conversations to their own topics of interest while also addressing specific topics at hand. Independent guided presession work allowed participants to gather knowledge at their own pace prior to each session, which likely contributed to more active and in-depth participation.

INTRODUCTION

The American Public Health Association has declared racism a public health crisis and asserted that racism is a fundamental cause of illness.1 The legacy of structural racism in the United States affects patients, providers, and learners; health care and medical education are implicated in this legacy.2 Whereas the suffering of White communities has been medicalized, health care in the United States has long disregarded, criminalized, and even exacerbated the suffering of communities of color, particularly Black communities.3 Furthermore, racial inequities have been revealed within the academic medical environment, including medical student evaluations, NIH funding, and faculty promotion processes.4-6 Academic medical centers shoulder the responsibility of addressing health inequities and creating environments where Black students and faculty members can thrive.7

The death of George Floyd in May 2020 led to renewed and increased awareness of longstanding racism and anti-Blackness in the United States. In this setting, various medical institutions and medical societies released statements condemning racism and injustice in medicine and society more broadly.8-10 Many have committed to incorporating antiracist content into their curricula.11

Historically, medical education has emphasized a biomedical approach with focus on pathophysiology over the social and structural determinants of health.12 Alternative medical education pedagogies have been proposed to teach students to critically engage with the relationship between structures such as racism and health.13-15

Critical race theory (CRT), first introduced in the 1980s, provides a race-conscious framework with which to examine inequity, power, and justice within a given social structure. The major tenets of CRT include the understanding of the ubiquity of racism, intersectionality, and interest convergence.16 CRT has been incorporated into law, political science, and other fields but, thus far, medicine has failed to formally embrace its teachings.

- Identify personal emotional responses to racism in the United States.

- Become familiar with the basic tenets of CRT.

- Understand how historical constructions of race have shaped systemic racism today.

- Apply a CRT framework to issues relating to emergency medicine.

METHODS

We developed a series of five virtual workshop sessions in 2019 that were held over Zoom in June and July 2020 in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fifteen incoming emergency medicine interns at the University of California–San Francisco were invited to participate in the curriculum on a voluntary basis. Nine learners showed interest in the curriculum and opted in to participate. Ultimately, eight learners completed the curriculum; most participants identified as members of racial groups overrepresented in medicine. All sessions were facilitated by the creators of this curriculum; both of the facilitators had prior experience guiding workshop discussions related to topics of race. Sessions were held weekly during 5 consecutive weeks for between 90 and 120 min. Participation in individual sessions was limited by learner work schedules; attendance for learners was not mandatory.

Prior to each session, learners were provided presession materials including podcasts, recorded lectures, and readings. Presession materials did not exceed 2 h of work. Guiding questions were also provided with presession materials to facilitate reflection. Materials were curated to provide foundational knowledge on CRT and U.S. history as well as local history of the San Francisco Bay Area.

Session I provided historical context for current civil unrest and asked participants to explore emotions related to these events and history learned and unlearned. Session II introduced the basic tenets of CRT and followed the historical construction of a racial framework in the United States.

Session III explored the history of policing in the United States and asked participants to consider public safety. Session IV identified the racist history of medicine and its impact on health care today. Session V examined the history of racism and activism in San Francisco and culminated with direct application of curriculum material toward constructing projects to undertake toward achieving health justice.

Participants were provided pre- and postcurriculum surveys to assess satisfaction and comfort with topics related to racism and CRT. They also received surveys after each individual session and were able to provide timely feedback to the facilitators throughout the curriculum. In this first iteration of the curriculum, learners were not assessed on knowledge retention or application of principles.

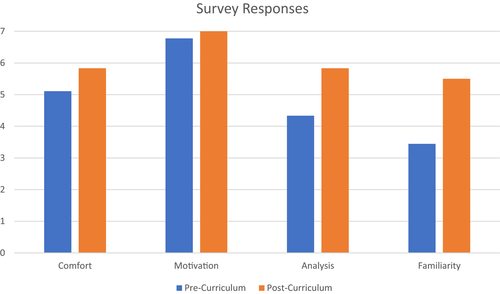

Pre- and postcurriculum surveys were optional and anonymous and asked participants to select responses on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) relating to comfort engaging with topics of racism, motivation to learn more about topics of race and racism, analysis of issues of race and racism, and familiarity with CRT (Table 1). Respondents also provided qualitative feedback. Postcurriculum surveys additionally assessed overall curriculum experience.

| Comfort | Motivation | Analysis | Familiarity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precurriculum (n = 9) | 5.11 | 6.78 | 4.33 | 3.44 |

| Postcurriculum (n = 6) | 5.83 | 7.00 | 5.83 | 5.50 |

| p-value | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

RESULTS

Participants rated the curriculum as useful (mean = 6.67) and found that the curriculum met their expectations (mean = 6.67). Participants also reported that their perspective had been changed after completing the curriculum (mean = 6.17).

- I particularly enjoyed that each session had a theme. It allowed me to have more focus, especially since race/racism is such a broad topic. It made the approach less intimidating.

- The size of the group, the pace, the semi-structure and flexibility of topics, the combination of theory-based and action-based discussion, and the phenomenal facilitation were all highlights!

- I like the progression in thematic content. I think the editorial choices for the topics were also really well done, and I liked the local histories coming in last as a segue towards future local action.

- I enjoyed that we were able to talk about how we felt, but sometimes these discussions led us down a rabbit hole and we had difficulty expanding beyond those initial thoughts. Overall though I appreciated how you tried to make sure we covered all the suggested readings during our discussions.

- I do think it needs to have more critical theory framing recognizing it is hard with everyone coming from different levels of knowledge.

DISCUSSION

Participants universally found our CRT curriculum useful (responses ranging from agree to strongly agree). As shown in Figure 1, despite low statistical power, survey data may suggest increased comfort and sustained motivation discussing topics of racism among participants. There was also a statistically significant increase in familiarity with CRT among participants (p = 0.01). Learners were nearly significantly more likely to report having a framework for analyzing topics of race and racism (p = 0.07); this is critical for engaging with these and related topics in the future.

Implementation of the curriculum was challenged by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic; the virtual format may have altered the learning environment. Our first session was meant to construct a safe space and build emotional connection as a way of mitigating physical distance.

Opt-in participation contributed to a very engaged cohort of learners and the small group size led to active participation by all learners. Semistructured facilitation allowed participants to guide conversations to their own topics of interest while also addressing specific topics at hand. Independent guided presession work allowed participants to gather knowledge at their own pace prior to each session, which likely contributed to more in-depth participation. Because this curriculum emphasized critical analysis and engagement over fact-based knowledge, it may be applied beyond graduate medical education to both undergraduate and continuing medical education. The workshop series might be incorporated into medical student advanced electives in emergency medicine, faculty development programming, and education efforts for all staff in the emergency department.

LIMITATIONS

While the opt-in participation and small cohort size were identified as strengths by participants, they also likely limit the analysis and scalability of this curriculum. A follow-up iteration of this curriculum with a larger cohort size will likely be required to better evaluate generalizability of our findings. Implementation of this curriculum also requires facilitators with expertise and experience guiding workshops on race-related topics. Our success with the virtual format presents the opportunity for programs and institutions with limited numbers of qualified facilitators to collaborate with other institutions to enact this type of curriculum.

CONCLUSIONS

The first iteration of our curriculum successfully promoted effective engagement with topics of race and racism by learners; participants reported increased familiarity with CRT as a framework and, relatedly, were nearly significantly more likely to report having a framework with which to analyze topics of race and racism. Our positive experience with independent guided presession work and a virtual format present an opportunity to expand our curriculum to other institutions including those that lack qualified facilitators. Additionally, we anticipate that learners outside of emergency medicine and graduate medical education could benefit from appropriately modified versions of this curriculum. Moving forward, we will be incorporating the feedback from this initial cohort of learners to engage a second cohort; particularly, we will aim to better account for participants’ variable baseline knowledge levels and provide longitudinal support for projects borne out of the curriculum. We will require more data to more fully evaluate and refine our curriculum, but this initial iteration represents an important step toward advancing racial justice in emergency medicine education.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.