Cobb syndrome effectively treated with trametinib

Abstract

Cobb syndrome is a rare neurocutaneous disease characterized by vascular anomalies involving the skin and spinal cord at the same metamere. The most common initial symptoms are neurological manifestations such as pain, monoparesis, headache, scoliosis, and motor damage. We present two patients with Cobb syndrome and severe disease burden harboring somatic mutations in KRAS. The two patients were subsequently treated with the MEK inhibitor trametinib, indicating the potential therapeutic benefit of this treatment for patients with life-threatening Cobb syndrome who are currently considered incurable.

Introduction

Cobb syndrome, a rare neurocutaneous disease, is characterized by vascular anomalies involving the skin, soft tissue, and spinal cord at the same metamere.1, 2 In general, Cobb syndrome is mostly diagnosed in childhood and presents with cutaneous stigmata, sensory/motor neurological deficits, and pain. Cobb syndrome can be accompanied by various clinical phenotypes of vascular anomalies, of which arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) involving the spinal cord and soft tissue are the most widely mentioned in previous studies.3, 4 Due to the complex angioarchitecture of spinal AVMs, the management of Cobb syndrome is challenging. Conventional treatments such as surgical resection, endovascular embolization, and radiosurgery are considered risky and less effective. Halting the progression of neurological deficits is the most critical goal of Cobb syndrome treatment.

In recent years, RAS-related genes, such as those encoding KRAS and MAP2K1, have been implicated in brain and spine AVMs, suggesting that targeted therapy, such as trametinib, may be beneficial for some patients. While these studies have prompted investigations into the Ras pathway, which is a target for Cobb syndrome, few patients have been treated. Although a previous study indicated that intracranial AVMs may not be sensitive to trametinib, we present two patients successfully treated with MEK inhibitor therapy for KRAS-positive refractory Cobb syndrome, suggesting a novel treatment strategy for inoperable and/or therapeutically challenging Cobb syndrome.

Case Presentation

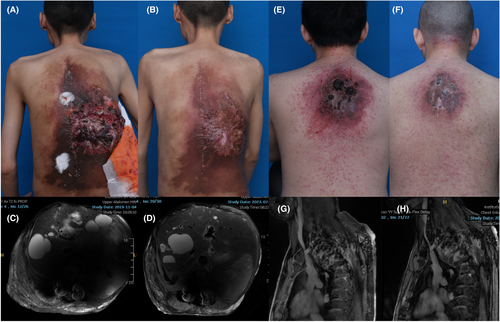

Patient #1: A male patient presented with asymptomatic erythema on his back at birth until age 15, at which time he had sudden weakness of the right lower limb. Over the next 5 years, due to developing lesions on his back, he presented with progressive lower extremity weakness, kyphosis, scoliosis, and related restrictive breathing disorders and an inability to engage in any exercise, including activities of daily living. He was initially treated with spinal AVM excision, kyphotic correction, and multiple endovascular embolization procedures with absolute ethanol. However, interventional embolization led to refractory ulcers in his back, further aggravating the patient's burden (Fig. 1A). He developed shock due to abdominal AVM hemorrhages and infection of the back ulcers in 2019. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging revealed a metameric AVM in the back with cutaneous, soft tissue, and intramedullary components, revealing the diagnosis of Cobb's syndrome (Fig. 1C). We collected the patient's blood after embolization and performed cfDNA testing to identify the molecular mutation type. Deep-coverage next-generation sequencing (NGS) of >10,000× detected a somatic variant, p.Gln61His, c.183A>C, at a 3.77% frequency in the KRAS gene (Table 1). Considering the patient's recurrent hemorrhages, poor quality of life and concern for imminent deterioration, the patient began oral trametinib 1 mg/day in 2021 and was treated continuously for ~2 years. Within 4 weeks of starting the medication, the patient reported subjective improvement, with resolution of coughing, dyspnea, and orthopnea. After 6 months of treatment, he experienced further improvement in his restrictive breath disorder and recurrent hemorrhages. After more than 2 years of treatment, the refractory ulcers on his back had completely healed (Fig. 1B). Magnetic resonance imaging revealed significant resolution of the soft tissue and spinal AVMs (Fig. 1D). Overall, trametinib therapy was well tolerated and was only accompanied by a mild acneiform rash that was quickly resolved.

| Patient no. | Gene | Chr:posi | Ref>alt | Geno | Depth (RD + AD) | Mutation frequency | Impact | Annotation | hgvs_c | hgvs_p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KRAS | 12:25380275 | T>G | 0*1 | 4539 + 178 | 0.0377 | Moderate | Missense_variant | c.183A>C | p.Gln61His |

| 2 | KRAS | 12:25398287 | G>GCTC | 0*1 | 2414 + 161 | 0.0621 | Moderate | Inframe_insertion | c.29_31dupGAG | p.Gly10dup |

Patient #2: A 36-year-old male patient with a red mass on the back and 6 months of lower extremity weakness without a history of trauma. He was initially treated with oral thalidomide and multiple endovascular embolization with absolute ethanol. However, his condition did not improve after treatment, the vascular masses subsequently grew rapidly, and he developed repeated ruptures and bleeding (Fig. 1E). Magnetic resonance imaging revealed significant kyphosis below the cervical segment and soft tissue vascular masses in spanning levels C5 to T3 involving the spinal canal, including destruction of the vertebral body, consistent with the diagnosis of Cobb syndrome (Fig. 1G). Considering the continued progression of the patient's neurological symptoms and bleeding, we performed molecular analysis with postembolization cfDNA and subsequent targeted therapy. Deep-coverage NGS revealed a somatic variant, p.Gly10dup,c.29_31dupGAG, at a 6.21% frequency in the KRAS gene (Table 1). The patient began oral trametinib 1 mg/day in 2023 and was treated continuously for more than 1 year. Within 3 months of starting medication, the patient reported subjective improvement in his lower extremity weakness. After 1 year of treatment, the lesions on his back shrank, the ulcers healed, and he could walk upright (Fig. 1F). Magnetic resonance imaging revealed reduced AVM lesions in the soft tissue, edema, and reduced flow voids in spinal lesions (Fig. 1H). Other than a mild acne-like rash, no adverse reactions were reported.

Discussion

Cobb syndrome, first described by Cobb in 1919, is a rare but devastating neurocutaneous disease marked by characteristic vascular anomalies involving the skin, soft tissue, and spinal cord at the same metamere.1 Arteriovenous malformations of the spine are the major phenotype of Cobb syndrome and can lead to neurological signs or symptoms.3-5 The majority of diagnoses are made in children, and the most common initial symptoms are neurological manifestations. Based on the anatomic location, size, and progression of spinal AVMs, patients with Cobb syndrome can experience pain, hemiplegia, scoliosis, motor injury, and even subarachnoid hemorrhage, acute paralysis, and paraplegia.4, 6, 7 These clinical manifestations may have a sudden onset with rapid progression or become progressively worse and last for decades. Due to the rarity of Cobb syndrome and the complex vascular architecture of spinal AVM lesions, there is currently no consensus on the optimal treatment strategy. Traditional treatments include conservative treatment, surgical resection, and endovascular embolization, with the goal of halting neurological decline, preventing further deterioration, and achieving neurological recovery.4, 5, 8, 9 However, treatment via surgical resection or endovascular embolization is challenging and invasive and has a high probability of disease recurrence. Therefore, identification of a more effective and less invasive treatment for Cobb syndrome is urgently needed.

In recent years, genomic evaluation of intracranial and extracranial AVMs has shown that RAS/RAF/MEK pathway gene mutations, such as those in KRAS and MAP2K1,10, 11 are likely drivers of AVM, suggesting the potential use of MEK inhibitors in intracranial and extracranial AVMs.12 However, a previous report of a patient with Cobb syndrome showed that trametinib was effective at treating extracranial AVMs but not spinal cord AVMs, raising concerns about the sensitivity of CNS AVMs to trametinib therapy.13, 14

In this report, we describe two patients with Cobb syndrome who harbored NRAS mutations, which we suspect is the cause of the vascular abnormalities of the patients. Both patients presented with kyphosis/scoliosis, restrictive breathing disorders, mobility disorders, and recurrent bleeding. After repeated endovascular interventional embolization, the patients' symptoms improved only slightly, and complications such as refractory ulcers were even observed. Within months of therapy initiation, the patient's clinical status changed significantly, with major improvements in walking and breathing disorders and almost complete resolution of bleeding. On follow-up imaging, the patient's spine and soft tissue AVM lesions were significantly reduced.

The genetic identity of AVMs demonstrates the safety and effectiveness of this targeted molecular therapy, and identifying effective biosamples is central to treatment management. For patients with Cobb syndrome, peripheral AVM tissue biopsy may lead to bleeding problems, while open surgical biopsy of spinal AVMs is not possible due to the risk of stroke. Therefore, we demonstrated a method with postembolization cfDNA samples, which has proven to be a safe and accurate method for the specific genetic diagnosis of vascular malformations.15 This technique is less invasive than other methods and helps determine which patients will respond most favorably to targeted therapies, in addition to expanding our understanding of the molecular genetics of complex vascular diseases. The relatively low dose used in this study highlights that a low dose of trametinib can be sufficient for treating Cobb syndrome and is likely to minimize side effects during treatment compared with the side effects of the higher doses that are used for treating tumors.

Conclusion

In this study, we reported two patients with Cobb syndrome who were successfully treated with the MEK inhibitor trametinib, which indicates the potential therapeutic benefit of this treatment for patients with life-threatening Cobb syndrome who are currently considered incurable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to show our deepest gratitude to the patient for sharing their clinical information.

Funding Information

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Nos. 82304045 and 82203948), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Funded Project (Project Nos. 2022M720088 and 2023T160422), Shanghai sailing program (Project No. 23YF1422200 and 22YF1422400), Specialist League Development Foundation of Shanghai 9th People's Hospital (Project Nos. ZKLM-介入1, ZKLM-介入2).

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data of this article are included in the submitted manuscript.