First-ever acute ischemic strokes in HIV-infected persons: A case–control study from stroke units

Abstract

Objective

The stroke risk for persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIVs) doubled compared to uninfected individuals. Stroke-unit (SU)—access, acute reperfusion therapy—use and outcome data on PLHIVs admitted for acute ischemic stroke (AIS) are scarce.

Methods

AIS patients admitted (01 January 2017 to 31 January 2021) to 10 representative Paris-area SUs were screened retrospectively from the National Hospitalization Database. PLHIVs were compared to age-, initial NIHSS- and sex-matched HIV-uninfected controls (HUCs). Outcome was the 90-day modified Rankin Scale score.

Results

Among 126 PLHIVs with confirmed first-ever AIS, ~80% were admitted outside the thrombolysis-administration window. Despite antiretrovirals, uncontrolled plasma HIV loads exceeded 50 copies/mL (26% of all PLHIVs; 38% of those ≤55 years). PLHIVs' stroke causes by decreasing frequency were large artery atherosclerosis (LAA), undetermined, other cause, cerebral small-vessel disease (CSVD) or cardioembolism. No stroke etiology was associated with HIV duration or detectable HIVemia. MRI revealed previously unknown AIS in one in three PLHIVs, twice the HUC rate (p = 0.006). Neither group had optimally controlled modifiable cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs): 20%–30% without specific hypertension, diabetes, and/or dyslipidemia treatments. Their stroke outcomes were comparable. Multivariable analyses retained good prognosis associated solely with initial NIHSS or reperfusion therapy. Older age and hypertension were associated with CSVD/LAA for all PLHIVs. Standard neurovascular care and reperfusion therapy were well-tolerated.

Interpretation

The high uncontrolled HIV-infection rate and suboptimal CVRF treatment support heightened vigilance to counter suboptimal HIV suppression and antiretroviral adherence, and improve CVRF prevention, mainly for younger PLHIVs. Those preventive, routine measures could lower PLHIVs' AIS risk.

Introduction

Improved combined antiretroviral therapies (cART) enable persons living with HIV (PLHIVs) to achieve near-normal lifespans.1 Since 2000, PLHIV numbers >50 years have tripled and will reach 73% of that population by 2030.1 Most of today's middle-aged PLHIVs are mainly pre-cART-era survivors, with long HIV-infection durations, more profound past immunodepression, exposure to first-generation ART, and less strict plasma HIV-RNA control that was available.1, 2 Hence, despite successes against acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illnesses (ADIs), cART-treated, middle-aged PLHIVs have a higher than expected risk of developing age-associated comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease [CVD]), than HIV-uninfected counterparts.2 Indeed, over 20 years, PLHIVs' global CVD burden has tripled and their stroke risk doubled compared to uninfected individuals.1-3 These higher rates of CVD and ischemic stroke (IS), the most frequent type,4 reflect the complex interplay of overrepresentation of modifiable CV risk factors (CVRFs), metabolic toxicity of older ART agents, and HIV-driven chronic immune activation and inflammation.1, 5

Stroke mortality for PLHIVs is three times higher than for HIV-uninfected controls (HUCs) and their low SU-admission rate is associated with higher mortality of stroke victims.6 Indeed, either PLHIV stroke is not reported to the neurology department or >24 hours have lapsed since symptom onset.6 Because “time-is-brain” is one of the most fundamental aspects of acute stroke management, identifying a possible stroke when confronted with a sudden-onset neurological deficit is—now and for the years to come—one of the new challenges for physicians caring for PLHIVs. Nowadays, non-ADIs and, notably, CVD currently outweigh ADIs.7 Whether tailored stroke treatment is indicated for PLHIVs with multi-comorbidities, potentially making them more vulnerable to reperfusion therapies and hemorrhagic complications, is debated.1, 3, 8 Knowing their stroke profile is required to plan current and future appropriate therapeutic strategies.8-10

This study was undertaken to address the limited information available on direct stroke unit (SU) access, care procedures, acute reperfusion therapy use, and outcomes for PLHIVs admitted for AIS, versus matched HUCs, and to provide “real-world” information on cART-treated PLHIVs within the 90–90–90 (90% of diagnosed PLHIVs, 90% of them on cART, and 90% of those treated being virally suppressed) continuum-of-care target.8-11 Indeed, the importance of using timely, up-to-date data to ensure that findings are relevant to current treatment regimens is acknowledged and can improve aging PLHIVs' care and outcomes. CVRFs were also compared between populations.

Patients and Methods

Study design

This multicenter, retrospective, and case–control study analyzed data from the National “Programme for the Medicalization of Information Systems” (PMSI), which exhaustively records all discharges from French hospitals. PMSI information (01/01/2017–31/01/2021) for all consecutive PLHIVs ≥18 years old admitted to any of the 10 major, certified, Paris-region SUs with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 diagnosis of cerebral infarction (163), unspecified stroke (164) and HIV infection (B20–24), was extracted. PLHIVs were matched 1:1 to the first random HUC admitted during the same calendar period for age (±5 years), sex and initial National Institute of Health Stroke Score (NIHSS; 0–10; 11–20; ≥21). Only eight hemorrhagic strokes were identified, so analyses were restricted to patients with first-ever AIS, confirmed by experienced stroke investigators (R.S. and I.R.), according to international diagnostic criteria.12 HIV infection was based on medical history or a positive in-hospital test. Exclusion criteria were stroke mimic, known previous stroke, ongoing brain opportunistic infection (OI) or malignancy. The Paris region represents 18.2% of the French population (12,000,000 inhabitants) and has the highest PLHIV prevalence, ~40,000 individuals.

The Hôpital Fondation Rothschild Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective analysis of an anonymized database (IRB00012801; 10/26/2016; no. CE_20161027_9_AMR) and waived patients' written informed consent. Non-opposition was obtained.

Assessments

From each patient's chart, we collected sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle (tobacco, alcohol, and drugs), HIV/AIDS history (hepatitis, opportunistic infection(s), and neoplasia), immunological and virological findings, modifiable CVRFs, and their specific treatments. Certified SUs complied with international recommendations12 for standardized diagnoses, stroke definitions, and treatment-procedure protocols for all included patients. Results of diagnostic procedures, including mainly carotid ultrasound, transcranial Doppler ultrasound, EKG, transthoracic and/or transesophageal echocardiogram and/or Holter monitoring were recorded. AIS etiologies were classified based on the TOAST classification.13 Patients' poststroke outcomes were evaluated with modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at SU discharge and month-3 poststroke visit. mRS scores of 0–1 or 0–2, respectively, defined excellent or good 3-month functional outcomes.

Outcomes

The primary objective was to compare good month-3 prognoses (mRS≤2) between PLHIVs and HUCs. Their AIS etiologies were also compared. Stroke-associated factors were analyzed according to different etiologies (cerebral small-vessel disease (CSVD)/large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) and cardioembolic/undetermined) for all PLHIVs and those >55 years with CSVD/LAA etiology.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were computed with R software (v4.0.3). Descriptive statistics are reported as number (%) for qualitative variables or median [interquartile range (IQR)] for quantitative variables. For percentage calculations, missing values were excluded from the denominator. Quantitative variables were compared with Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test, when appropriate, and qualitative variables with chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test, when necessary. Univariable and multivariable logistic-regression analyses identified associations between predictive factors and stroke etiologies, and good prognosis and HIV status or stroke etiologies. Complete or quasi-separation, multivariable logistic-regression analyses were computed using Firth's penalized-likelihood approach. Multivariable regression models included covariates already known to be linked to the dependent variable or that achieved p < 0.2 in the univariable analysis. Covariates with >15% missing values were excluded. All tests were bilateral and computed with a two-sided significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

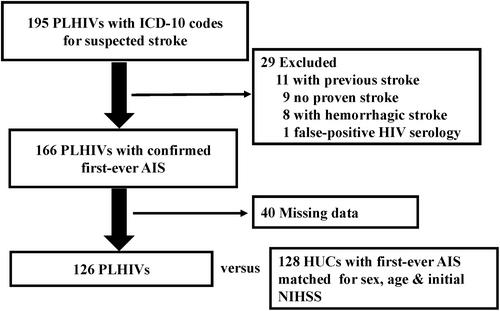

PMSI search identified 82,565 patients, including 240 PLHIVs, 195 (81%) of whom had been hospitalized in participating SUs. To attempt AIS exhaustivity, we included ICD-10 code 164 (not specified stroke as hemorrhage or infarction) and recruited 6% and 4% of hemorrhagic strokes in PLHIVs and HUCs, respectively (p = 0.8). Subsequent analyses considered only AIS patients. Final analyses, after removing 19 PLHIVs with exclusion criteria, 40 incomplete charts and eight hemorrhagic strokes, concerned 126 PLHIVs (Fig. 1). PLHIVs' and HUCs' clinical characteristics (Table 1) were comparable among SUs (p > 0.9).

| Characteristic | PLHIVs (n = 126) | HUCs (n = 128) | p * | PLHIVs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤55 years (n = 62) | >55 years (n = 64) | p * | ||||

| Subjects | ||||||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age, years | 56 [47–64] | 55 [48–63] | 0.9 | |||

| ≤55 years | 49% | 52% | 0.7 | |||

| Males | 76% | 76% | 0.9 | 69% | 83% | 0.08 |

| HIV infection | ||||||

| Estimated HIV duration, years | 15 [9–22] | 13 [6–21] | 18 [11–23] | 0.1 | ||

| Current CD4+ cells/μL | 501 [296–778] | 446 [222–753] | 529 [300–788] | 0.4 | ||

| CD4+ nadir, cells/μL | 143 [60–378] | 109 [39–217] | 244 [83–439] | 0.1 | ||

| plVL | <50 [<50–239] | <50 [<50–665] | <50 [<50–<50] | 0.04 | ||

| Current undetectable plVL | 73% | 62% | 85% | 0.01 | ||

| CD4/CD8 ratio | 0.60 [0.3–1.0] | 0.6 [0.2–1.1] | 0.4 [0.3–0.8] | 0.7 | ||

| Previous neurological events | 12% | 20% | 6% | 0.06 | ||

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||||

| Hypertension | 49% | 48% | 0.9 | 38% | 61% | 0.01 |

| Current antihypertensive use | 82% | 75% | 0.4 | 88% | 78% | 0.5 |

| Diabetes | 18% | 16% | 0.7 | 11% | 24% | 0.07 |

| Current antidiabetic use | 70% | 90% | 0.1 | 71% | 69% | >0.9 |

| Dyslipidemia | 34% | 29% | 0.3 | 24% | 43% | 0.03 |

| Current lipid-lowering–drug use | 81% | 76% | 0.5 | 69% | 90% | 0.1 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24 [22–29] | 26 [23–29] | 0.4 | 24 [22–29] | 25 [22–29] | 0.7 |

| ≥30 | 19% | 20% | 0.9 | 20% | 19% | >0.9 |

| Addiction (mainly cannabis) | 16% | 14% | 0.7 | 23% | 15% | 0.6 |

| Current smoker | 36% | 46% | 0.1 | 36% | 6% | >0.9 |

| Alcoholism | 26% | 24% | 0.8 | 27% | 24% | 0.9 |

| Sleep-apnea syndrome | 5% | 11% | 0.4 | 11% | 0% | 0.3 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||||

| ≥2 | 56% | 61% | 0.5 | 47% | 66% | 0.03 |

| ≥3 | 28% | 34% | 0.3 | 19% | 35% | 0.04 |

- Values are median [interquartile range] or number (%).

- HUCs, HIV-uninfected controls; PLHIVs, persons living with human immunodeficiency virus; plVL, plasma HIV load.

- * Significantly different p values are in bold type.

Half of the PLHIVs were first referred to an emergency department before being admitted to an SU. Hence, 80% were admitted outside the reperfusion therapy window. Overall, PLHIVs' and HUCs' characteristics were comparable for comorbidities, even recreational drug use (Tables 1 and 2). PLHIVs' median age was 55 [range 24–92] years. HIV infection had been diagnosed before 1996 for 30%; it was discovered or untreated at stroke admission for 10. Compared to older PLHIVs, those ≤55 years had significantly more frequently uncontrolled infections, and significantly lower hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia and ≥2 or ≥3 CVRF rates (Table S1). Table 2 reports the etiological TOAST classification.

| Characteristic | PLHIVs (n = 126) | HUCs (n = 128) | p * | PLHIVs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤55 years (n = 62) | >55 years (n = 64) | p * | ||||

| Type | 0.8 | >0.9 | ||||

| Wake-up stroke | 24% | 24% | >0.9 | 22% | 24% | 0.9 |

| Unknown previous stroke on MRI | 33% | 18% | 0.006 | 30% | 37% | 0.4 |

| CSVD on MRI | 41% | 31% | 0.1 | 20% | 61% | <0.001 |

| Ischemic stroke etiology | ||||||

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 34% | 34% | >0.9 | 24% | 43% | 0.02 |

| Cardioembolism | 12% | 16% | 0.4 | 11% | 13% | 0.8 |

| Cerebral small-vessel disease | 13% | 6% | 0.07 | 3% | 22% | 0.002 |

| Undetermined | 24% | 28% | 0.4 | 29% | 19% | 0.2 |

| Others | 17% | 16% | 0.8 | 32% | 3% | <0.001 |

| Initial NIHSS | ||||||

| Whole population | 3 [1–6] | 2 [1–5] | 0.1 | 3 [1–6] | 4 [1–7] | 0.6 |

| Location | ||||||

| Anterior cerebral artery | 6% | 5% | 0.6 | |||

| Middle cerebral artery | 63% | 59% | 0.05 | |||

| Posterior cerebral artery | 6% | 7% | 0.8 | |||

| Vertebrobasilar territory | 26% | 21% | 0.3 | |||

| Multiple territories | 11% | 13% | 0.6 | |||

| Acute reperfusion therapy | ||||||

| Yes | 20% | 18% | 0.7 | 18% | 19% | 0.9 |

| Intravenous thrombolysis solely | 17% | 16% | 0.8 | |||

| Endovascular therapy | 9% | 10% | 0.7 | |||

| Time from stroke onset (min) | 163 [137–207] | 179 [147–185] | >0.9 | 185 [157–201] | 160 [135–200] | >0.9 |

| Contraindication | 54% | 49% | 0.4 | 59% | 50% | 0.5 |

| Out-of-window therapy | 83% | 79% | 0.6 | 80% | 87% | |

| Prognosis at discharge | ||||||

| NIHSS at discharge | 1 [0–3] | 1 [0–2] | 0.2 | 1 [0–3] | 1 [0–3] | 0.6 |

| mRS score | ||||||

| <2 | 57% | 62% | 0.4 | 65% | 65% | >0.9 |

| ≤2 | 75% | 81% | 0.2 | 80% | 76% | 0.7 |

| Admission-to-SU discharge interval, days | 7 [4–12] | 6 [3–11] | 0.3 | 8 [4–15] | 6 [3–10] | 0.1 |

| Admission-to-home interval, days | 8 [4–15] | 5 [3–11] | 0.02 | 10 [4–16] | 7 [4–14] | 0.2 |

| Carotid endarterectomy for stenosis | 2% | 6% | 0.4 | |||

| Prognosis at 3 months: mRS score | ||||||

| <2 | 66% | 77% | 0.06 | 65% | 65% | >0.9 |

| ≤2 | 80% | 87% | 0.1 | 65% | 65% | >0.9 |

- Values are median [interquartile range] or number (%).

- HUCs, HIV-uninfected controls; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Score; PLHIVs, persons living with human immunodeficiency virus; SU, stroke unit.

- * Significantly different values are in bold type.

Stroke etiologies were comparable for PLHIVs and HUCs, with only a trend toward more frequent CSVD for PLHIVs. Etiologies differed significantly between PLHIVs, with LAA and CSVD predominating in older PLHIVs, and other causes more frequent for the younger PLHIVs. Other causes, for PLHIVs versus HUCs, respectively, were infectious vasculitis (11, mainly due to varicella zoster and syphilis, vs. 0), arterial dissection (5 vs. 8) and patent foramen ovale (3 vs. 8). The middle cerebral artery was the only arterial territory significantly more affected in PLHIVs than HUCs. Comparing patients treated with acute reperfusion therapies versus those without, respectively, median NIHSSs at admission were more likely to be higher for PLHIVs (8 [5.0–15.0] vs. 2 [1.0–4.0]) than HUCs (6 [3.5–17.5] versus 2 [1.0–3.0]); p < 0.001 for both. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed previously unknown IS twice as frequently for PLHIVs than HUCs (33% vs. 18%; p = 0.006). The admission-to-home interval was significantly longer for PLHIVs than HUCs.

Because of the relatively small numbers of patients in some etiological subgroups, we grouped CSVD and LAA, as they share the same main vascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension and diabetes). We also combined undetermined etiologies that might contain cardioembolic ones because subcutaneous cardiac rhythm monitoring had not been done for all patients. Multivariable analyses retained initial NIHSS or acute reperfusion therapy as the only significant independent predictors of PLHIVs' good prognosis (Table 3). Age and hypertension were significantly associated with CSVD/LAA etiology (Table 4). No CVRF was associated with cardioembolic/undetermined stroke for all PLHIVs. Neither HIV duration nor detectable HIVemia was associated with any stroke etiology. Only hypertension was significantly associated with CSVD/LAA etiology for PLHIVs >55 years old.

| Adjusted covariates | n | Good prognosis (yes/no) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p * | ||

| Logistic regression | 240 | ||

| HIV status | 0.44 [0.17–1.07] | 0.08 | |

| Age | 0.97 [0.93–1.01] | 0.1 | |

| Male sex | 1.05 [0.34–3.03] | 0.9 | |

| Initial NIHSS | 0.73 [0.65–0.80] | <0.001 | |

| Acute reperfusion therapy, yes | 17.55 [3.37–136.50] | 0.002 | |

| Stroke-to-admission interval, days | 1.00 [0.99–1.01] | 0.5 | |

| Firth logistic regression | 202 | ||

| CSVD/LAA etiology | 0.99 [0.37–2.62] | >0.9 | |

| Age | 0.95 [0.91–1.00] | 0.04 | |

| Male sex | 1.18 [0.36–3.86] | 0.8 | |

| Initial NIHSS | 0.74 [0.66–0.82] | <0.001 | |

| Acute reperfusion therapy, yes | 10.54 [1.71–64.84] | 0.01 | |

| Stroke-to-admission interval, days | 1.00 [0.99–1.01] | >0.9 | |

- CSVD, cerebral small-vessel disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LAA, large artery atherosclerosis; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Score.

- * Significantly different values are in bold type.

| Factor | Univariable OR [95% CI] | p * | Multivariable OR [95% CI] | p * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSVD/LAA, PLHIVs all ages | n = 126 | |||

| Male sex | 1.01 [0.44–2.32] | 0.98 | – | |

| Age (years) | 1.06 [1.03–1.10] | <0.001 | 1.05 [1.01–1.09] | 0.02 |

| Hypertension, yes | 3.63 [1.76–7.75] | <0.001 | 2.44 [1.10–5.45] | 0.03 |

| Dyslipidemia, yes | 2.39 [1.13–5.16] | 0.024 | 1.33 [0.56–3.14] | 0.5 |

| Diabetes, yes | 3.27 [1.28–9.14] | 0.017 | 1.94 [0.68–5.85] | 0.2 |

| Smoking, yes | 1.02 [0.49–2.12] | 0.96 | – | |

| Detectable plVL, yes | 0.36 [0.12–0.96] | 0.050 | – | |

| HIV-infection duration at the time of stroke (years) | 1.03 [0.99–1.08] | 0.16 | – | |

| Cardioembolic/undetermined cause, PLHIVs all ages | n = 126 | |||

| Male sex | 1.40 [0.59–3.52] | 0.46 | – | |

| Age (years) | 0.99 [0.97–1.02] | 0.71 | – | |

| Hypertension, yes | 0.57 [0.27–1.20] | 0.14 | 0.64 [0.30–1.37] | 0.3 |

| Dyslipidemia, yes | 0.68 [0.30–1.47] | 0.33 | – | |

| Diabetes, yes | 0.43 [0.13–1.18] | 0.12 | 0.49 [0.15–1.39] | 0.2 |

| Smoking, yes | 0.71 [0.32–1.53] | 0.39 | – | |

| Detectable plVL, yes | 1.35 [0.53–3.43] | 0.53 | – | |

| HIV-infection duration at the time of stroke (years) | 0.98 [0.93–1.02] | 0.35 | – | |

| CSVD/LAA, PLHIVs >55 years old | n = 64 | |||

| Male sex | 1.11 [0.26–4.20] | 0.88 | – | |

| Hypertension, yes | 5.42 [1.82–17.49] | 0.0032 | 4.60 [1.49–15.21] | 0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia, yes | 1.67 [0.58–4.98] | 0.35 | – | |

| Diabetes, yes | 5.19 [1.26–35.44] | 0.043 | 3.89 [0.86–27.80] | 0.1 |

| Smoking, yes | 1.52 [0.52–4.71] | 0.45 | – | |

| Detectable plVL | 0.38 [0.07–1.94] | 0.24 | – | |

| HIV-infection duration at the time of stroke (years) | 1.03 [0.97–1.11] | 0.31 | – |

- PLHIVs, persons living with human immunodeficiency virus; CSVD, cerebral small-vessel disease LAA, large artery atherosclerosis; plVL, plasma HIV load.

- * Significantly different values are in bold type.

Discussion

In France, 92% of cART-treated PLHIVs have plasma virus loads (plVLs) ≤50 copies/mL (https://anrs-co4.fhdh.fr). Herein, 26% of cART-treated AIS PLHIVs had disproportionately high, uncontrolled infections (>50 copies/mL; 38% of those ≤55 years old). Our results agree with all14-18 but one study5 reporting high plVLs associated with increased stroke incidence. Notably, plVLs >400 copies/mL ranged from 27%15 to 42%,14 57%,16 and up to 63%17 of PLHIV stroke victims. Indeed, recent high viremia (HIV RNA >200 copies/mL) tripled the stroke and transient ischemic attack risk.18

That >80% of PLHIVs were addressed to an SU, far exceeds the 60% SU admission for the Paris-area general population.19 However, ~80% of PLHIVs and HUCs were admitted outside the thrombolysis-administration window, and >50% had been transferred to the SU after emergency-department admission. Unavoidably responsible for late reperfusion therapy, that time loss resulted in significantly poorer prognoses.3 Pertinently, as for another series,3 ~20% of our PLHIVs and HUCs with the highest NIHSSs received reperfusion therapy. Acute thrombolysis afforded no significant impact on PLHIVs' discharge and month-3 mRS scores, possibly because of their initial low NIHSSs.3 Indeed, PLHIVs were usually admitted to SUs for minor AIS, close to the median NIHSS of 4 for the 20-year-older general population living in the Paris area (unpublished Agence Régionale de Santé data). No major complications (e.g., symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage or death) occurred, supporting reports of thrombolysis safety in PLHIVs.3, 8, 9

The CVRF burden, including smoking and recreational drug use, was comparable for PLHIVs and HUCs. PLHIVs' CVD frequency agreed with those reported previously.5, 14, 17, 20 Traditional CVRFs (hypertension, diabetes and/or dyslipidemia) were not treated optimally for 20–30% of both groups. While ≤12% of the 55- to 64-year-old general population consulted their general practitioners twice a year in France (fr.statistica.com) and despite the French national HIV guideline recommending biannual monitoring visits, only one-thirds of PLHIVs did so and only half had annual check-ups.21 Our findings agree with those previously reported,5, 20, 22 underscoring suboptimal medical care for PLHIVs, despite free-of-charge medical coverage in France. Primary and secondary prevention underutilization is more relevant for PLHIVs because of their heightened HIV-related CVD risk.22 Our findings echo the often-repeated importance of optimizing their CVD-risk prevention and treatment.

Our first-ever AIS PLHIVs were ~20 years younger than the general population with stroke, as usually reported.3, 11 Mean age for all Paris-region comers with first-ever stroke is 72 years, with only 20% them in the 45–64-year age-range.23 Although the mean age of PLHIVs with stroke rose from 36.9 years in 1997 to 51.3 years in 2012, mean age alone cannot explain their increased AIS number.11 Indeed, HIV infection itself contributes strongly to the overall stroke burden and is a major risk factor for stroke in younger PLHIVs, with a 42% population-attributable fraction.24

One-third of PLHIVs had previously unknown IS, independent of age, twice the rate for HUCs, potentially because of suboptimally treated, modifiable CVRFs and HIV-infection. Pertinently, silent IS is associated with an approximately twofold higher risk of future stroke.25 Because non-ADIs—notably CVDs—are now the most frequent HIV-infection complications, an acute focal neurological deficit must implicitly evoke a possible stroke rather than OI or lymphoma. Although Thakur et al.26 described a very different series of uncontrolled Afro-American PLHIVs and Gutierez et al.27 non-Hispanic Black PLHIVs, our observations accord with theirs. However, herein, once the AIS was recognized, no differences between PLHIVs and HUCs were observed in SU access, management times and percentages receiving reperfusion therapy.

Published evidence showed that immunovirologically controlled PLHIVs had a lower AIS frequency, and that the stroke risk for those with high CD4+ T-cell counts and low plVLs no longer exceeded that of the general population.28, 29 Similarly, for PLHIVs with immune recovery and cART-controlled plVLs, regardless of sex, the relative risk of myocardial infarction is no longer elevated.30 However, continuous exposure to even low HIV titers induces persistent low-grade systemic inflammation, notably driven by interleukin-6.31 Independently of conventional CVRFs, interleukin-6 plays a key role in AIS pathogenesis in the general population and its higher circulating levels are linearly associated with greater long-term risk of incident AIS.32 Interleukin-6 levels are associated with residual plVLs and increased significantly as soon as plVL reached 31 copies/mL.31 As underlined by previously reported findings, poorly controlled HIVemia might contribute more strongly to stroke risk than HIV itself,14, 18 despite detectable HIVemia not being associated with a poorer prognosis. Encouraging PLHIVs into care and retaining them are essential to maintaining plVLs <50 copies/mL, and might prevent strokes18 and facilitate functional recovery.26, 33

As previously reported,3, 6, 17 stroke etiologies decreased in frequency from LAA to undetermined, other cause, CSVD and cardioembolism, and were globally comparable for PLHIVs and HUCs. Strokes of unknown cause affect ~30% of the general population.34 LAA, CSVD and cardioembolism are the main stroke etiologies for PLHIVs.4, 16, 26 However, PLHIVs >55 (vs. ≤55) years had more comorbidities and their AISs were more often associated with traditional CVRFs.21 Consequently, LAA and CSVD also predominated for our PLHIVs >55,4 with doubled CSVD rates,20 and other causes responsible for those ≤55. None of our PLHIVs had HIV vasculopathy/vasculitis, which are apparently less common in cART-treated PLHIVs with plVLs <50 copies/mL; hence, optimal adherence may achieve inflammation levels similar to HIV-uninfected individuals.31 OI-related strokes mainly occurred in severely immunosuppressed PLHIVs.4, 6 Thus, our findings differed from those of PLHIVs from other countries, like Malawi,24 or sub-Saharan Africa, where stroke disproportionately affects cART-naïve, young individuals at advanced HIV-infection stages,10, 24 engendering OI, HIV vasculopathy and immune-reconstitution inflammatory syndrome overrepresentation.10, 24

Several IS series before 2017 were not conducted in SUs with incomplete investigations (reviewed in1, 3, 35). Moreover, some studies were hampered by small sample sizes,3, 8 high percentages of uncontrolled HIV infections,4, 14, 17, 18, 24, 36 numerous PLHIVs not on cART,8, 36 concurrent OI10, 24 and high frequencies of active drug abuse (e.g., methamphetamine, cocaine, and/or heroin).4, 8, 17

Immediate or late outcomes of first-ever PLHIV and HUC AISs did not differ significantly. CSVD, more frequent in middle-aged PLHIVs than the general population, might increase symptomatic, post-intravenous-thrombolysis, intracerebral hemorrhage risk and poor poststroke outcomes.37 Previous observations were contradictory, with either worse outcomes6, 10, 11 or no differences,8, 38 as we found. As for the general population, worse first-ever AIS outcome was associated with lower SU admission rates.6

Overall, PLHIVs had significantly more median in-SU days than HUCs, without differing between PLHIVs by age. In the Paris area, ~50% of middle-aged PLHIVs experience social deprivation.39 Although potentially reflecting HIV-comorbid complications, we hypothesized, based on published observations, that isolation would be mostly responsible,11 as family members usually assist most first-ever AIS survivors reappropriate daily-living activities.

The study strengths are its large regional sample size, application of stroke ICD-10 codes, and standardized SU management that enhanced the accuracy and thoroughness of the stroke work-up. Our cohort is representative of PLHIVs in western countries, where >90% are successfully treated but our findings may not be generalizable to more vulnerable PLHIVs. Nevertheless, UNAIDS 2021 world epidemiological data showed that 85% of PLHIVs are aware of their seropositivity, 88% of PLHIVs knowing their HIV status are cART-treated and 92% of those cART-treated PLHIVs' plVLs were below the detection threshold (unaids.org). Those worldwide data highlight the unsuitability of reporting results concerning virologically uncontrolled cART-treated PLHIVs.

Although consistent with reported findings,8, 9, 38 the absence of between-group prognosis differences might reflect diminished statistical power due to the few patients with high mRS scores. Our study's limitations are those inherent to national hospital-based studies. Nevertheless, PMSI is a validated tool, providing accurate information on cerebrovascular diseases.40 In this context, atrial fibrillation and OI might have been underestimated without long-term cardiac monitoring or lumbar puncture, particularly among “undetermined strokes.”36 However, all PLHIVs were followed by their infectious diseases department and no other causes were subsequently identified. Because age disparity is a significant variable that might have affected the frequency of stroke subtype15 and door-to-needle time in the SU,41 our control group was age-matched.

To conclude, as PLHIVs age and modifiable CVRFs persist, stroke prevalence will likely continue to rise. While new highly efficacious all-in-one cART have made AIDS a chronic disease like any other, they may have contributed to less exigent supervision, like early during the HIV era. High percentages of uncontrolled HIV infections, suboptimally treated CVRFs and probably insufficient biannual PLHIV-monitoring emphasize the importance of optimizing preventive measures, mainly for younger PLHIVs, and the need for enhancing vigilance to counter suboptimal HIV suppression. Those cost-effective, preventive measures that do not require complex equipment or technology could lower PLHIVs' stroke risk.25 Notably, PLHIV care has changed significantly since most longitudinal studies evaluating PLHIV CVD risk were conducted before 2000.35 Stroke education must also be reinforced in the 90–90–90 setting. Any acute neurological deficit in PLHIVs should primarily evoke a stroke, with patient SU admission to assure reperfusion therapy administration within the limited therapeutic window. There will always be time for secondary referral to an infectious diseases unit.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janet Jacobson for editorial assistance, and Dr Aurélien Schaffar for extracting data from PMSI database.

Authors Contributions

R.D., M.M, M.O., and A.M.: contributed to the conception and design of the study; R.D., J.C., I.R., and A.M.: contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. R.D., M.M., C.D., B.L., T.D.B., E.M., H.H., A.L., D.M., C.L., M.O., and A.M.: contributed to drafting the text.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the study findings are available upon reasonable request of qualified researchers.