The effect of disaster case management on housing recovery: Analysis of disaster survivor support in Sendai City using the synthetic control method

The Japanese version of this paper was published in Volume 87 Number 797, pages 1282–1293, https://doi.org/10.3130/aija.87.1282 of Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ). The authors have obtained permission for secondary publication of the English version in another journal from the Editor of Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ). This paper is based on the translation of the Japanese version with some slight modifications.

Abstract

This study investigated how disaster case management (DCM) and disaster public housing reconstruction influence housing recovery using 4 open-data sources. The trends in the number of households under designated temporary housing in Sendai and 18 other cities in Miyagi Prefecture were analyzed. The results revealed that both DCM and the reconstruction of public housing for disaster recovery promote housing restoration from temporary housing. Finally, Mary Richmond's discussion of wholesale and retail methods was used to elucidate policy implications for disaster victim support.

1 Introduction

1.1 Background

A critical element of relief work following a major disaster is housing recovery; specifically, rehousing residents who are now homeless [Note 1]. This task requires the national government, local governments, and relief organizations to coordinate with each other to provide evacuation shelters, arrange temporary housing, and ultimately experience permanent housing recovery. Research on post-disaster housing recovery notes that rather than just being a physical structure, a home is also the foundation for people's lives. Therefore, a delay in rebuilding this foundation means a delay in the recovery of victims' entire lives.1 Meanwhile, post-disaster housing recovery presents an opportunity: with the right relief projects and urban planning, national and local governments can rectify pre-disaster patterns of inequality and exploitation.2 Guided by these insights, policymakers in Japan have developed housing recovery programs aimed at rebuilding the foundations of victims' livelihoods. One example is the provision of disaster recovery public housing (DRPH; Fukkō kōei jūtaku). This is public housing stock provided to victims at discounted rates.

Japan's approach to post-disaster recovery contributes to the recovery of homes and daily life. However, it has also attracted criticism, particularly for its use of grade of building damage as a yardstick for determining what assistance should be provided, if any. Analyzing a survey conducted in Sendai City after the Great East Japan Earthquake disaster, Sugano3 noted examples where the extent of damage was not commensurate with the level of need for emergency assistance (or other social needs). Maki4 questioned the validity of requiring building-damage grade certificates to be eligible for disaster victim support. The author also revealed that the government started using this benchmark only after the Great Hanshin Earthquake of 1995, as it was just criteria for applying the Disaster Relief Act for a specific disaster.

Following the March 2011 disaster, Japan introduced disaster case management (DCM), which emerged in the United States, to ensure that it could cater to the needs left unserved by when building damage is used as the yardstick. DCM has been praised for providing personalized hands-on support—support that is tailored to the particular needs of each household.3, 5, 6 In the Japanese context, DCM has been defined as “a process that provides personalized assistance to disaster victims by reaching out to the victims, identifying their particular circumstances (extent of damage, needs), and then developing and collaboratively a support package tailored to these circumstances”.6 DCM has seen considerable rollout in Japan. For instance, it has been applied in various forms in the areas affected by the March 2011 disaster as well as in Kumamoto and Tottori Prefectures. Although praised by people on the frontlines of post-disaster recovery, as of 2021, DCM is yet to be formalized into official post-disaster institutions (the measures in Tottori Prefecture are an exception). This lack of institutional integration may be because the Japanese literature on DCM remains scarce. Furthermore, few empirical studies in Japan have validated the quantitative assessments of the effects of DCM interventions. This study empirically analyzes the effect of a DCM intervention in Sendai City on housing recovery when compared with conventional interventions (DRPH provision, group relocation arrangements).

The remainder of this study proceeds as follows. First, in the rest of this chapter, we review the literature on housing recovery after the March 2011 disaster; outline the DCM programs of interest, officially known as the Program to Facilitate the Life Recovery (Hisaisha seikatsu saiken suishin purōguramu; hereafter, the Program to Facilitate) and Program to Expedite the Life Recovery (Hisaisha seikatsu saiken kasoku purōguramu; hereafter, the Program to Expedite); and present the purpose and value of this study. Next, Chapter 2 describes the methods. Chapter 3 describes Experiment 1, where we used the synthetic control method to analyze the effects of the DCM intervention on housing recovery. Chapter 4 discusses the issues identified in Experiment 1 and describes Experiment 2, where we analyzed the effects of the extraneous interventions (DRPH provision and mass relocation arrangements) on housing recovery. We also distinguish the effect of the DCM intervention from that of the extraneous interventions. Chapter 5 discusses the results of the study, their implications, and ongoing issues.

1.2 Literature on housing recovery after the Great East Japan Earthquake disaster

This section reviews the Japanese literature on housing recovery following the Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE) disaster, which is primarily targeted at Japanese readers. Studies after the GEJE disaster typically focus on community-level variation in housing recovery arising from the geographical extent of the damage and the extent to which the process is prolonged. Focusing on household preferences regarding housing recovery, Hirayama et al.,7 Tsukuda et al.,8 and Yamanaka et al.9 used opinion surveys conducted at multiple time points to trace how these preferences change over time, and how these changes are predicted by household attributes and the pace of reconstruction. Maeda et al.10 examined the occurrence of household separation in the housing recovery process. Ito et al.11 and Tsukuda et al.12 explored factors that predict a household's final preferences regarding housing recovery. Two notable studies are Kondo and Karatani,13, 14 which explored households' self-led efforts for housing recovery. The authors revealed the resources that enable, and the advantages and disadvantages of self-led housing recovery. Finally, they argued that housing recovery programs should accommodate a wide range of household opinions on housing recovery.

Relatedly, research has also focused on a program that has played a key role in the housing recovery process since the March 2011 disaster: the designated temporary housing (DTH) program. Under this program, the government offers victims temporary accommodation in DTH in the private rental sector. Several studies have examined the program's advantages and disadvantages. Some studies have focused on the lives of victims. Meno15 noted that victims can be housed quicker in DTH than prefabricated temporary housing. Furthermore, the author noted that the DTH program can find a home design (in terms of surface area) that matches the household size. According to Shigekawa et al.,16 because of this better matching, residents in DTH complained less than those in prefabs. The authors also noted that the DTH program encouraged users to live independently as it rehoused the users in communities, where they could live among residents unaffected by the disaster. Meanwhile, Tanaka & Shigekawa et al.17 highlighted a drawback of the program: as the properties used in the program are dispersed across a large area, DTH dwellers were often isolated from their community. This isolation can be particularly problematic in households with care needs, such as households with a member who has a disability and single-parent households. Compared to such cases, households resided in prefabs can easily access support, and thus, had a higher subjective sense of life recovery.5

Other studies have discussed the effects of the DTH program at a macro level. Shigekawa et al.16 noted that the program eases the strain on public finances as it requires no construction. Meanwhile, Meno18, 19 reported that the program created a population outflow; specifically, many victims had to move from their original neighborhoods into urban areas to reside in DTH, and many of these residents ended up settling permanently in the new area.

The DTH, with all its advantages and disadvantages, has been expanded in disasters subsequent to the March 2011 disaster. In the post-disaster process for the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake, DTH had a much greater share of the total temporary housing than that in the post-disaster process for the March 2011 disaster.20 DTH's use in future disasters may be even greater in urban areas, where authorities can obtain many private-rental properties for the program.

In summary, the literature on housing recovery since the March 2011 disaster has explored the process of housing recovery at a community level and highlighted the problems with this process. It has also discussed the issues concerning a more recent matter of public interest—the practical issues with the DTH program. However, less attention has been paid to a quantitative question: To what extent does government intervention expedite housing recovery?

1.3 DCM programs in Sendai

Here, we outline the DCM intervention in Sendai. Sendai City helped victims rebuild their lives through 2 DCM programs. The first DCM program was the Program to Facilitate the Rebuilding of Victims' Lives, formalized in March 2014 and launched the following month [Note 2]. The second was the Program to Expedite the Rebuilding of Victims' Lives, formalized in March 2015 and launched in the following month [Note 3]. This study analyzes both programs as examples of DCM. In brief, both programs involve casework in which officials visit households to identify the household's characteristics needs and then deliver assistance tailored to the household's particular set of socioeconomic circumstances.

In an ethnography of disaster victims in Sendai, Shigekawa21 analyzed narratives from officials in charge, revealing the workflows for both programs. Specifically, once top-down, hard-infrastructural interventions (DRPH deployment and group relocation arrangements) were underway, the programs were formulated to assist victims in accordance with the prospective interventions [Note 4]. Regarding the duration of assistance, an official revealed that the support measures for both programs were delivered on the premise that the temporary housing issue would be resolved (ie, the occupants could move out of the temporary housing into permanent housing) within the 5-year timeframe envisaged in the reconstruction plan: “The idea was that both programs would serve as concrete measures for implementing the housing recovery within the 5-year reconstruction period” [Note 5]. The author also noted a Sendai-specific feature in the program: visiting advisory roles were taken by elderly individuals with broad career experience. According to Shigekawa et al.,21 as Sendai's population is larger than that of neighboring municipalities, it was important for the programs to deploy people with extensive life experience.

To identify which residents require assistance, Sendai City officials visited and interviewed affected households. Then, officials applied the results of the interviews onto a matrix where one axis described feasibility of housing recovery (feasible vs. unfeasible) and the other described the household's ability to live independently (absence vs presence of need for assistance). The 4 quadrants in this matrix were as follows: (1) capable of recovering livelihood; (2) requires housing recovery assistance; (3) requires assistance in daily living; and (4) requires both assistance in daily living and housing recovery assistance [Note 6]. After identifying the households that required assistance, Sendai City then determined exactly what assistance it would provide to each of these households.

Next, we describe the DCM casework we focus on as the intervention of interest and its effect household recovery [Note 7]. The Program to Facilitate focuses on the following measures. Besides providing DRPH, it uses household survey data to determine the housing recovery plan, ensure that the necessary information is communicated, provide advisory support, and provide jobseeker support if necessary. For instance, if the person is unlikely to find work, then the program may provide employment support using other programs under the Act for Supporting the Independence of Persons in Need (Seikatsu konkyūsha jiritsu shien hō). The program also provides telephone-based help for finding suitable rental accommodation in the private sector. For instance, for particularly needy cases, ward offices and Sendai City (specifically, the reconstruction and recovery division) would collaborate with a working group formed of members of the Sendai City Council of Social Welfare and nonprofit organizations (NPO) to develop an assistance plan for the household. They would then organize household visits and other forms of assistance based on the plan. Depending on the issues the household faces, consultations with lawyers or other professionals may be provided. Next, the Program to Expedite includes the same measures as the first along with additional measures to reinforce the assistance. For example, it coordinates with legal professionals in cases where legal arrangements are necessary for furthering the housing recovery process. In situations where households struggle with the rehousing process for some reason, the program provides hands-on support; specifically, program officials accompany households during property-searching tours and the rental agreement process.

1.4 Purpose and value of this study

The purpose of this study was to analyze the effect of the DCM intervention provided by Sendai City after the March 2011 disaster (the Program to Expedite and the Program to Facilitate) on housing recovery compared to that of conventional post-disaster interventions (DRPH provision, group relocation arrangements). Here, the outcome variable “housing recovery” exclusively refers to cases where DTH occupants move out of their DTH housing after securing permanent accommodation; thus, this definition excludes cases where prefab occupants move out of their prefab housing into permanent accommodation. Given the choice between one or the other, we chose to focus on housing recovery among victims dwelling in DTH but not those dwelling in prefabs (the conventional form of emergency accommodation) because of 2 reasons. First, in the context of the March 2011 disaster, rehousing in DTH has emerged as a new practical problem and research theme. Second, DCM programs, with their focus on personalized casework, play an even more critical role for DTH occupants, who are likely to be isolated.

This study consisted of 2 experiments. In Experiment 1, we analyzed the effect of Sendai City's 2 DCM programs on housing recovery. In Experiment 2, we analyzed the effect of Sendai City's DRPH program. Comparing the 2 sets of results, we highlight the value of the 2-fold approach to post-disaster assistance: personalized casework, as represented by the 2 DCM programs, combined with a macro-institutional approach, represented by the DRPH program. Thus, we relate this to Mary Richmond's22 2 approaches to social work: the wholesale and retail methods.

Crucially, while this study is concerned with how 2 DCM programs contribute to housing recovery, we must also recognize that housing recovery is but one area where DCM can play a role. DCM has a much broader scope; it can assist victims in rebuilding various aspects of their lives.

2 Method

2.1 Datasets

Both experiments used 4 datasets. These data sources and the set of variables are outlined below.

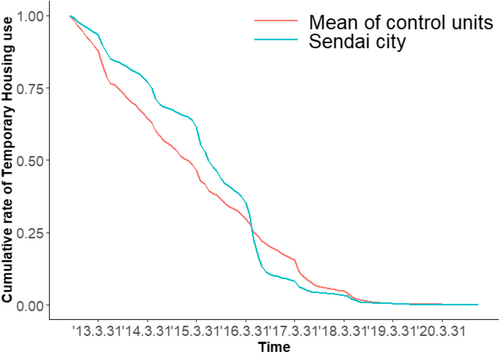

The first dataset is the Dataset for DTH Use in Miyagi Prefecture. We built this dataset from a dataset published on Miyagi Prefecture's official website showing the numbers of households in DTH [Note 8]. These statistics show the numbers of DTH occupants between August 2012 and December 2020 by month (101 time points), with some exceptions [Note 9]. From these statistics, we prepared panel data (a longitudinal dataset) showing the number of DTH-dwelling households in the 36 municipalities of Miyagi Prefecture across 101 time points. We eliminated from the panel data those municipalities that peaked at <100 (fewer than 100 households dwelling in DTH), leaving 18 municipalities for analysis. We excluded these municipalities for 2 reasons: First, in municipalities where only a few households ever dwelt in DTH, a single case of housing recovery would exert an outsized impact on our approximations. Second, such municipalities are likely to differ markedly from Sendai, undermining their validity as comparison municipalities. Next, for each remaining municipality, we converted the quantities in the time series into percentages to show the cumulative decline in the rate of DTH use, scaling the quantity for August 2021 at 100%. We assembled our first dataset in this way. It represents panel data showing a cumulative decline in DTH use for 19 municipalities (the remaining 18 municipalities and Sendai City) across the 101 time points. Figure 1 shows DTH use rate in Sendai City compared with the mean rate for the 18 other municipalities (the control units). DTH use rates differ between Sendai and the control mean from before March 2014, March 2014 being the time when the DCM intervention was enacted. Given that the rates differed from the outset, we concluded that the entirely unadjusted mean for the 18 municipalities is unsuitable as a comparison for the rate in Sendai City.

The second dataset is the DRPH Dataset. It is derived from Miyagi Prefecture's online listings of the completed DRPH units in each prefectural municipality [Note 10]. By referring to these listings, we determined the completion rate for each of the 101 time points between August 2012 and December 2020, scaling the final number of completed units at 100%. As with the first dataset, we presented these completion rates as panel data. The panel data ultimately included the completion rate across 101 time points for 14 of the 19 municipalities from our first dataset; we excluded 5 of these municipalities because we could not confirm how many DRPH units were provided there. We used this dataset to examine interaction between DRPH completion rate and THR use rate.

The third dataset consists of covariates that we used to construct a synthetic control. The covariates included municipality-specific sociodemographic variables gleaned from national survey data and damage status. Table 2 lists these independent variables. Some variables specify the time of data collection (eg, “as of March 1, 2013”), while others do not. The latter were gleaned from the 2010 census.

The fourth dataset is Sendai City's Open Data on Temporary Housing Use [Note 11]. This dataset shows 2 items of data pertaining to DTH-dwelling households in Sendai City: (1) when the households moved out of their DTH; and (2) their permanent housing types. Using this dataset, we calculated DTH use rate by final rehousing arrangement across the 101 time points. During Experiment 2, we used this data to discern the influence of extraneous interventions (DRPH provision and group relocation arrangements).

2.2 Analytical framework

To evaluate the success of a government intervention, actual outcomes must be compared with the outcomes that would have occurred in the hypothetical case that the government had not implemented the intervention. Such counterfactual outcomes are latent outcome variables; they evade direct experimental observation. Success in establishing causality depends to a great extent on how one postulates the latent outcome variables.

The most effective method for postulating latent outcome variables is a randomized control trial (RCT). However, an RCT is unfeasible in many fields of inquiry owing to ethical issues and resource constraints. Disaster recovery studies are no exception; it would be ethically questionable, for example, to randomly allocate some individuals to the treatment condition of receiving assistance for rebuilding lives and other individuals to the control condition of not receiving such treatment.

Fortunately, several experimental designs are available as alternatives to a RCT. These are known as quasi-experiments. A quasi-experiment uses observable criteria to control the analytical design and statistically curate the covariates, thereby creating similar conditions to those in an RCT. In this way, a quasi-experiment can be used to elucidate causality as accurately as possible to evaluate the government intervention. Notable quasi-experimental designs include propensity score analysis, regression discontinuity design, instrumental variables estimation, and difference-in-differences. This study uses the synthetic control method, which is an extension of difference-in-differences.

The idea of the synthetic control method is to assemble a sample of units that never received the intervention of interest (ie, Sendai City's DCM) and use the weighted average of these units as a counterfactual (synthetic) control against which the outcomes of the intervention on the treated unit (Sendai City) can be compared. In brief, we first assembled a sample of comparative municipalities (municipalities in Miyagi Prefecture other than Sendai City). The weighted average of these municipalities represented a hypothetical “Sendai City” that was never exposed to the DCM intervention. We then compared housing recovery trends between the actual and the synthetic versions to determine the effect of the DCM intervention. For examples of the synthetic control method applied here, see Abadie et al.23, 24

2.3 The synthetic control method

Here, we outline the synthetic control method in more detail, referring to Abadie et al.23, 24 [Note 12]. First, we postulate a sample of J + 1 units, where j = 1 is the treated unit (the unit that received the intervention) and j = 2 to j = J + 1 are untreated units (units that never received the intervention). Here, the latter units constitute a reserve of potential comparison units (“donor pool”). Next, we assume that the sample is arranged as panel data in which all units are observed at the time points t = 1, …, T. We also assume several pre- and post-intervention time points, T0 and T1, respectively, such that T0 + T1 = T. Here, j = 1 is Sendai City, while j = 2 to j = 19 is the “donor pool” of potential comparison municipalities. The pre- and post-intervention periods are as follows: t = 1 to t = 19, T0, is the pre-intervention period; this period begins in August 2012, when data on temporary housing occupancy were first published, and lasts until March 2014, the month in which the first DCM program, Program to Facilitate, was launched. The post-intervention period is t = 20 to t = 101, T1.

To ensure that the intervention can be evaluated as accurately as possible, the synthetic control should be the weighted average of the control units (the units in the donor pool). The synthetic control is formulated by a (J × 1) vector of weights W = (w2, …, wj + 1), with 0 ≤ Wj ≤ 1 and w2 + … + wj+1 = 1. For W (the weight), one should select a value that resembles the pre-intervention characteristics of the treated unit as closely as possible.

In the above equation, vm represents the relative importance we assign to the mth variable when measuring the difference between X1 and X0W. The R Package for Synthetic Control (Synth) computes the vm weights to minimize the mean squared prediction error (MSPE) between the pre-intervention characteristics of the treated unit and synthetic control. Here, we use Synth and SCtool to compute the synthetic control.

3 Experiment 1: Outcome of DCM

3.1 Applying the synthetic control method

Table 1 shows the weights (W) assigned to the control municipalities representing the synthetic “Sendai City.” Three of the municipalities were assigned a weight of at least 0.001: Ishinomaki (0.666), Shiogama (0.333), and Tagajo (0.001). Therefore, we used these municipalities to construct the synthetic “Sendai City.”

| City | Weight (W) |

|---|---|

| Ishinomaki | 0.666 |

| Shiogama | 0.333 |

| Kesen-numa | 0 |

| Shiraishi | 0 |

| Natori | 0 |

| Kakuda | 0 |

| Tagajo | 0.001 |

| Iwanuma | 0 |

| Tome | 0 |

| Higashimatsushima | 0 |

| Osaki | 0 |

| Okawara | 0 |

| Shibata | 0 |

| Watari | 0 |

| Matsushima | 0 |

| Rifu | 0 |

| Tomiya | 0 |

| Misato | 0 |

Table 2 shows the covariate values for Sendai City and the synthetic “Sendai City.” The values are arranged in order of weight (V), as indicated in the rightmost column. As weight represents the relative importance of a given variable in the construction of the synthetic control, the greater the variable's weight and the closer the covariate values, the more suitable that variable is as a criterion for the synthetic control. Notably, the top 5 variables have a weight of at least 0.001. In each case, the covariate value for the synthetic control better resembles (the actual) Sendai City's covariate value than the mean covariate value (the mean for all 18 control municipalities) does.

| Variables | Sendai City | Synthetic control | Mean of control units | Weight V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative rate of temporary housing use (as of March 1, 2013) | 0.934 | 0.922 | 0.884 | 0.401 |

| Population densitya | 1334.9 | 1248.851 | 772.672 | 0.269 |

| Cumulative rate of temporary housing use(as of February 28, 2014) | 0.786 | 0.750 | 0.668 | 0.200 |

| Average of family members | 2.296 | 2.6 | 2.801 | 0.111 |

| Single rate | 0.406 | 0.241 | 0.208 | 0.018 |

| Ratio of households headed by female parent and children (single mother) | 0.071 | 0.094 | 0.083 | 0 |

| Owner-occupied houses rate | 0.489 | 0.710 | 0.736 | 0 |

| Death caused by disaster /pre-disaster population | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0 |

| Complete collapse houses/pre-disaster households | 0.066 | 0.254 | 0.089 | 0 |

| Percentage of population aged 65 and over | 18.579 | 27.343 | 23.943 | 0 |

| Percentage of population aged 75 and over | 8.727 | 13.777 | 12.304 | 0 |

| Ratio of single-person elderly households | 0.066 | 0.095 | 0.070 | 0 |

| Ratio of elderly couple households | 0.077 | 0.112 | 0.095 | 0 |

- a Variables without a time period are from the 2010 census.

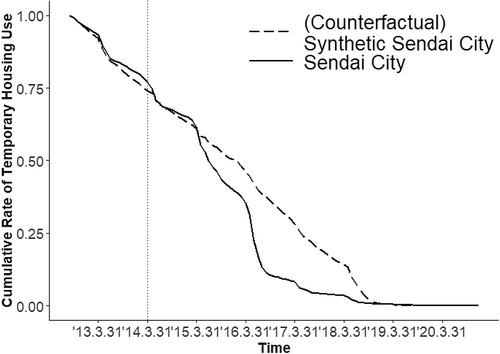

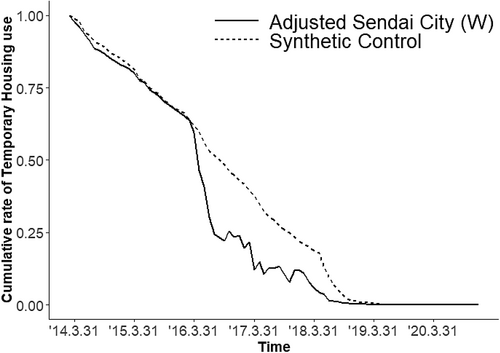

Accordingly, we used these weights to analyze the difference in DTH use rates between the synthetic and actual Sendai City. The results are shown in Figure 2. The dotted line running vertically from time point 14.3.31 is a reference line representing the time when the intervention began (initially as the Program to Facilitate), which was in April 2014. From the pre-intervention period until the end of the first year of intervention, the 2 cities trace a similar path in DTH use rate. However, from April 2015, the rate in the actual Sendai City declines at a markedly greater rate than that in the synthetic city. This implies that the DCM intervention (Program to Facilitate and Program to Expedite) seem to have been effective. However, for reasons discussed later, this difference does not immediately warrant such a conclusion. Rather, we must examine whether the observed trend is coincidental.

Figure 3 shows the results of a placebo test conducted on the synthetic control municipalities. Based on the procedure used while constructing the synthetic “Sendai City,” we constructed a synthetic control for all 18 comparison municipalities and then compared the placebo effects between the synthetic control and the actual 18 municipalities. The black line in Figure 3 indicates the difference between the actual and synthetic Sendai City, while each gray line indicates the difference in the placebo effect between 1 of the 18 municipalities and its synthetic control. We assumed that if the effects of the intervention (DCM) for Sendai City exceeded the effects of the placebo for the 18 municipalities, then this would imply that the former was no coincidence. As Figure 3 illustrates clearly this, the effect of the DCM intervention on housing recovery was no temporal effect or coincidence.

3.2 Discussion: An analytical issue and a method for resolving it

Next, while using a longitudinal dataset to examine the effect of a government intervention on housing recovery, we also need to consider the timing of the extraneous interventions. Here, these were DRPH provision and group relocation arrangements. Murao25 noted that the timing of DRPH provision varies by municipality. Accordingly, we needed to control for the effects of differences in the relative progress of such hard-infrastructure-led housing recovery (the timing of DRPH provision and group relocation arrangements). Moreover, we had no way of distinguishing the effects of the DCM and extraneous interventions.

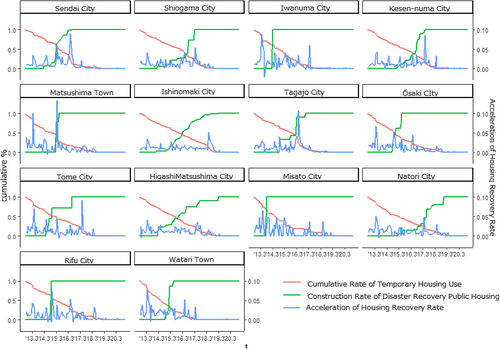

To understand the relationship between DRPH provision and housing recovery in each municipality, we plotted the graphs shown in Figure 4. The red line indicates the cumulative decline in DTH use in that municipality (red line). The blue line indicates the time-over-time change in DTH use; this is the difference between the DTH use rate at a given (t) and previous time points (t – 1). The green line indicates the DRPH completion rate. Note that Figure 4 includes only the 14 municipalities for which we could confirm the amount of DRPH units provided on the website.

These graphs yielded 3 observations. First, DRPH was provided quicker in Sendai than in the 3 municipalities with the highest weight values for the synthetic control: Ishinomaki, Tagajo, and Shiogama. Second, DRPH provision did not always expedite housing recovery, as shown by the absence of a faster cumulative decline in DTH use. In some municipalities, housing recovery proceeded apace before DRPH was completed; in others, DRPH availability scarcely affected the rate of housing recovery. Third, DTH use rate dipped sharply in Sendai City at 2 time points. Observations 1 and 3 were particularly germane to the results of Experiment 1; that is, they strongly implied that the observed outcome of DCM was in part the result of the influence of extraneous intervention on housing recovery.

Accordingly, in Experiment 2, we broke down housing recovery in Sendai City by 3 categories of permanent housing type arrangements: (1) resided in DRPH or relocated in group relocations; (2) made alternative arrangements independently; and (3) moved into private-rental property. This analysis enabled us to control for the influence of extraneous intervention on housing recovery, and thus, isolate the effect of the DCM programs.

4 Experiment 2: Analysis of the Influence of DRPH

4.1 Discerning the influence of extraneous intervention: DRPH provision and group relocation arrangements

The dataset “Sendai City's Open Data on Temporary Housing Use” records the time when the households in DTH moved out. It also includes the households' subsequent rehousing arrangements. By excluding cases in which the household moved into DRPH or relocated in a mass relocation from this dataset, we can control for the influence of the timing of the extraneous interventions. However, excluding such cases would imperil comparison with the synthetic control. That is, the synthetic “Sendai City” constructed from a combination of Ishinomaki Shiogama, and Tagajo cities include the compounding factor. Specifically, in the 3 cities, the decline in DTH use rate was in part the result of extraneous intervention. Hence, we assign the weights as described below to ensure that we can compare with the synthetic control.

This weighting ensures that the trends among households who received an extraneous intervention (households resided in DRPH and relocated in a mass relocation) is consistent with the equivalent trends in the synthetic control. By comparing the W(t) with the synthetic control, we can control for the influence of the households subject to extraneous intervention and analyze the effect of the DCM intervention among the remaining households (those who made alternative arrangements independently and moved into private-rental properties).

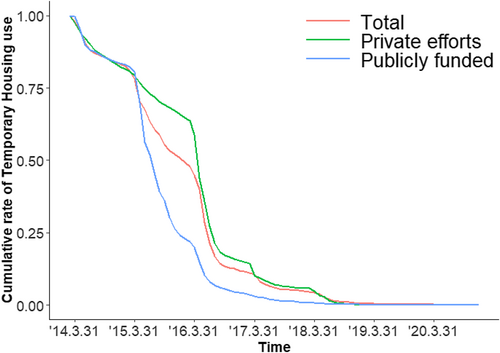

Before comparing the W(t), consider the variation between the rehousing arrangements. Figure 5 shows housing recovery trends from April 2014 onward (t > 19), as April 2014 is the time when Sendai City enacted the Program to Facilitate. The red line indicates the total cumulative decline in DTH use rate. The blue line indicates the decline among households that ultimately received extraneous intervention (DRPH or mass relocation). The green line indicates the decline among households who made alternative arrangements independently and those who moved into private-rental housing. First, DRPH provision contributed conspicuously to the overall pace of housing recovery from April 2015 onward; thereafter, there is a sudden surge in households moving out of DTH and into DRPH. Second, there is a surge in instances of private rehousing arrangements (making alternative arrangements independently or moving into private-rental properties) from April 2016. The latter observation is particularly relevant to evaluate the effect of the DCM; this surge suggests that the DCM programs achieved their purpose in the 5-year timeframe envisaged in the reconstruction plan.

Next, we compared the adjusted “Sendai City” W(t) obtained from Equation (2) with the original synthetic control. Figure 6 shows the housing recovery trends in the adjusted “Sendai City” and synthetic control during t > 19. First, up to April 2016, the adjusted “Sendai City” resembled the synthetic control much closer than the actual Sendai City did. This suggests that we successfully controlled for the effect of DRPH, which was provided earlier in Sendai City than it was in the 3 constituent municipalities of the synthetic control (see Figure 4). Thus, the discrepancy between the synthetic control and adjusted “Sendai City” reflects the effect of the DCM intervention after controlling for the influence of the timing of DRPH provision.

4.2 Estimating the secondary effect: Rent reduction

We only considered 1 outcome variable: housing recovery, as measured by the rate of DTH-dwelling households moving out from their DTH. However, policymakers and practitioners supporting households in DTH may also be interested in another outcome variable, rent, which would not be considered in the case of assisting housing recovery among prefab dwellers. Specifically, to the extent that DCM expedites housing recovery by expediting an outflow from DTH, it would also expedite a reduction in the burden of rent associated with DTH occupancy. Thus, less DTH rent is paid than in the case where the DCM has not been implemented. Thus, rent reduction can be another key outcome variable to consider while evaluating the success of post-disaster recovery efforts in the future. Accordingly, we compute the amount of reduction in rent generated by the intervention using the data in Figure 6 and Sendai City's Open Data on Temporary Housing Use.

Table 3 shows the standard rents for DTH properties in Miyagi Prefecture according to Meno15 Rent is determined based on household size and floorplan. For each household-size category, we assigned the rent for the smallest floorplan for that household size (Column 4: Standard rent). Meno15 reported that around half of the households were paying rent somewhere between the standard level and 20 000 yen more than the standard level, the latter being classified as “upper rent.” Accordingly, we considered 2 rent parameters: standard and upper rent (standard rent +20 000 yen).

| Family size | N of households | Percentage | Standard rent (yen) | Upper rent (yen) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | 1598 | 32.4 | 32 000 | 52 000 |

| Two persons | 1211 | 24.6 | 42 000 | 62 000 |

| Three persons | 924 | 18.8 | 48 000 | 68 000 |

| Four and more | 1193 | 24.2 | 68 000 | 88 000 |

Next, we created a sample of 4926 “private rehousing” households (made alternative arrangements independently or moved into private-rental properties) from among the 7217 households who were dwelling in DTH as of t = 20 (April 2014) according to Sendai City's Open Data on Temporary Housing Use [Note 13]. Then, we grouped the households according to household-size categories (single, 2 persons, 3 persons, and 4 or more). Using each category's rent and share of the total sample, the weighted averages of standard and upper rent are 46 178.2 and 66 178.2 yen, respectively.

To express the contribution of the DCM intervention on these rent figures, we examined the difference in the area between the synthetic control and adjusted Sendai City (W) in Figure 6. The resulting value of 5.173 was then multiplied by the sum of this area by 4926 (the number of “private rehousing” households) to calculate the total instances of rent payment that would have occurred had the DCM intervention not been implemented. We then multiplied this total by the weighted averages of standard (46 178.2 yen) and upper rents (66 178.2 yen). Effectively, the DCM intervention yielded savings of 1 176 856 536 and 1 686 558 330 yen in standard and upper rent, respectively.

5 Discussion

We used the Dataset for Emergency Housing Use in Miyagi Prefecture to analyze the effect of Sendai City's post-disaster intervention, the DCM programs, on housing recovery. Three key findings emerge. First, housing recovery proceeded apace during 2015 and 2016. Second, the progress in housing recovery during 2015 was substantially driven by an extraneous intervention, DRPH provision. Third, in 2016, the progress in housing recovery among “private rehousing” households (made alternative arrangements independently or moved into private-rental properties) was a product of the intervention, particularly the DCM programs' delivery of personalized support to needy households in accordance with Sendai City's reconstruction plan.

Next, we discuss the validity and limitations of the study. We constructed a synthetic control representing Sendai City beginning from pre-intervention time points (before the first DCM program, the Program to Facilitate, was enacted). However, the synthetic control method measured the outcome in the treatment unit only and did not examine how the intervention would have affected the control units. Thus, our results offer no guarantee that a DCM intervention similar to that implemented in Sendai City would deliver a similar outcome in any of the 18 comparative municipalities. Rather, we compared Sendai City against a counterfactual version of the municipality itself. If anything, our findings are more likely to be replicated in a municipality of a similar scale to Sendai City (ie, an ordinance-designated city). This consideration is related to our decision to restrict the scope of the study to cases where households move out from DTH, not from prefabs. That is, in urban areas that can secure a sizeable reserve of vacant rental properties, DTH is likely to be used more extensively, as suggested by Sogabe et al.20 The author also reported the extensive use of DTH in the wake of the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake. Essentially, we argue that the effect of the intervention on housing recovery among DTH dwellers will be amplified in urban areas where use of DTH is high relative to other temporary housing arrangements.

The measures Sendai City enacted to help victims rebuild their lives were based on a 5-year reconstruction plan. According to this plan, the city delivered the 2 DCM programs and other interventions (DRPH provision, mass relocation arrangements). Insofar as this plan-based assistance can be considered a welfare approach to a social problem—that many victims do not experience housing recovery through their own efforts—the series of assistance measures for victims can be examined through the lens of social welfare.22 Mary Richmond, hailed as the mother of casework, advocated 2 approaches to social reform. First, the retail method, which involves using data on individual cases to deliver personalized care to these cases. Second, the wholesale method, which involves top-down institutional/legislative action. Of the 2 approaches, Richmond underscored the importance of the retail approach and developed a systematic casework methodology as a practical guide for this approach.26

To illustrate the differences between the 2 approaches, Richmond cited campaigns for child labor reform. To summarize, Richmond stated that legislating for child labor reform would be the wholesale approach; however, this approach only goes so far in remedying the problem. Real reform also requires a retail process that involves, “explaining the law and its enforcement to their employers, teachers, and parents, co-operating with the factory inspectors and with the school authorities … seeking out any individual cases of undue hardship caused by the sudden change, and making it possible for the children to remain in school without causing suffering in the family … informing the public about the iniquity of night work”.22 Corresponding, Sendai City's interventions to assist victims can be characterized as follows: Sendai City faced the need to assist victims in rebuilding their lives. To address this social problem, Sendai City updated its reconstruction plan so that alongside the existing wholesale approach of providing DRPH, it would also take a retail approach of delivering DCM programs that were designed to make the reconstruction plan a success. Consequently, victims experienced housing recovery (moved out from DTH) quicker than they would have otherwise. This observation is supported by the fact that the DCM programs were consistent with Richmond's example of child labor reform: they involved raising awareness, co-operating with related parties, and identifying individual cases unduly harmed by the changes. Furthermore, DCM can be considered synonymous with disaster casework. Today, in Japan, casework based on the retail approach is provided extensively to needy households in nonemergency times; however, in times of disaster, when needs are all the greater, such retail casework is rarely delivered institutionally.

Richmond's assertion that social reform requires both wholesale and retail approaches is supported by our findings. Specifically, to assist victims following a disaster, the reconstruction plan should be updated so that alongside wholesale measures such as DRPH provision, it also includes retail measures such as DCM programs designed to ensure the success of the plan. Japan has recently seen a considerable expansion of wholesale (top-down) post-disaster measures, including the System for Helping Victims Rebuild Their Lives. However, to improve the quality of disaster assistance, retail measures are also needed. The value of retail measures in times of nonemergency is well recognized; however, they should be used broadly in times of disaster too. Sugano27 used the loanword “phase-free” to express the idea that assistance for disaster victims should exist on a continuum with the assistance provided in times of nonemergency; hence, assistance is “freed” from the distinctions of nonemergency and emergency “phases.” Furthermore, the author emphasized the importance and scope of such “phase-free” assistance. Our study supports Sugano's assertions.

Regarding our findings on the savings in rent described in Section 4.2, Meno15 noted that actual DTH properties tend to charge rent close to the upper rent level. Therefore, the amount the DCM programs actually saved in DTH rent was probably midway between our 2 estimates. That is, although the DCM programs entailed steep running costs, they offset this to some extent by delivering DTH rent savings of at least 1 176 856 536 yen (the estimated savings in standard rent). As both the DTH and DCM programs are likely to be enhanced and expanded in future disasters, rent reduction may prove useful as a secondary outcome variable when evaluating a DCM intervention by providing a fuller picture of the intervention's outcomes.

Finally, we describe 2 ongoing issues. First, the purpose of the 2 DCM programs and that of the study differ. DCM programs' purpose was to assist victims in Sendai City in rebuilding their lives by having a variety of actors address the victims' needs related to restoring their daily lives and their needs related to housing recovery. Meanwhile, the purpose of this study was to examine the effect of the DCM programs on just housing recovery, not any other aspect of rebuilding lives. Future research into DCM should consider a wider array of outcome variables.

Second, the study considered only households that dwelt in DTH. DCM programs, along with other interventions such as DRPH provision, are designed to help all victims rebuild their lives; these interventions do not vary their scope of services depending on the extent of damage or the category of temporary housing that victims inhabit. Thus, our study captured only a limited aspect of how DCM programs can assist victims and the effects of other interventions (eg, DRPH provision); in reality, the effects would have been much greater. Nevertheless, by limiting its focus to victims dwelling in DTH, this study did reveal that the DCM intervention effectively delivered the designated goal—facilitating housing recovery among such victims.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fumio Nishizaki (Life Rebuilding Promotion Office, Post-Disaster Reconstruction Bureau, Sendai City) and Toshihiro Sato (Sendai City Council of Social Welfare) for their invaluable advice. This article is a product of research projects conducted under the Scenario Creation Phase of the Japan Science and Technology Agency, and Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society's Solution-Driven Co-Creative R&D Program for SDGs: Working with Welfare Professionals in Developing Basic Technology for National Rollout of Disaster Management that Leaves No One Behind [Fukushi senmonshoku to tomo ni susumeru “Dare hitori nokosanai bōsai” no zenkoku tenkai no tame no kiban gijutsu no kaihatsu] (JPMJRX19I8: November 15, 2019 to March 31, 2023; Representative: Shigeo Tatsuki; Basic Research A); Building and Systematically Testing Inclusive Disaster Management [Inkurūshibu bōsaigaku no kōchiku to taikeiteki jissō] (JP17H00851: Representative: Shigeo Tatsuki); and Examining the Effects of an Intervention for Assisting and Deploying Resources for Households Requiring Assistance to Rebuild Their Lives Following a Major Disaster [Daikibo saigai ni yoru seikatsu saiken yō shien setai ni taisuru shien shigen katsuyō no kainyū kōka no kentō] (JP20J15550: Grant-in-Aid for Fellows).

Disclosure

The authors have no conflict of interest.

NOTES

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.