Effect of pain neuroscience education and exercise on presenteeism and pain intensity in health care workers: A randomized controlled trial

Abstract

Objectives

Decreased workforce productivity has a significant economic impact on healthcare systems. Presenteeism, the practice of working at reduced potential, is more harmful than absenteeism. Present workers most often experience musculoskeletal pain that is not mitigated by general exercise or stretching. We aimed to assess whether a regimen of pain neuroscience education (PNE) and exercise tailored to individual healthcare workers could reduce presenteeism and improve productivity.

Methods

An independent investigator randomized 104 medical professionals into two groups (intervention and control). The control group received general feedback after answering a questionnaire, while the intervention group received a 6-month plan of exercises and PNE created by a physical therapist with 10 years of experience. Our primary outcome was the scores of the Japanese version of the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (WHO-HPQ) to investigate presenteeism; and our secondary outcomes were pain intensity, widespread pain index (WPI), and EuroQol 5-dimension (EQ5D-5L).

Results

In the intervention group, post intervention, we observed significant improvement in presenteeism, pain intensity, WPI, physical and psychological stress, and EQ5D-5L (P < .05). In the control group, we noted significant improvement only in the physical and psychological stress post intervention (P < .05). The results showed significant between-group differences in presenteeism post-intervention (P < .05).

Conclusion

We demonstrated that a combination of PNE and exercise decreases presenteeism of healthcare workers. Our findings will help healthcare facilities carry out better employee management and ensure optimal productivity.

Video Short

The roles of eosinophils and interleukin-5 in the pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps

by Gevaert et al.1 INTRODUCTION

Presenteeism is defined as workers being present at their jobs and completing their working hours, but not being able to function optimally because of an underlying illness or medical condition.1 The socioeconomic burden of presenteeism is estimated to be higher than absenteeism (loss of productivity that stems from being absent from work); per year the cost of absenteeism is $520 USD per person and of presenteeism is $3055 USD in Japan.2 Although presenteeism is also a risk factor for future absenteeism, thus detrimental for companies and corporations,3-5 it is not limited to office workers. Presenteeism is also rampant among healthcare workers, who are generally neglected because they are often thought to be immune to occupational hazards.6 Decreased workforce productivity due to high turnover, poor retention, presenteeism, and absenteeism has a significant economic impact on healthcare systems.7, 8

Conditions such as musculoskeletal pain, mental illnesses, and headaches can aggravate the economic burden due to presenteeism,2, 9-11 and managing them is important to avoid loss of productivity. Lower back or neck pain in workers can be improved by exercise,12 stretching13 and high-intensity training.14 However, a recent systematic review demonstrated that there is no strong evidence in favor of any intervention to treat or prevent lower back pain in medical workers,15 and neck-and-shoulder resistance exercises did not reduce absenteeism or improve the workability of office workers.16 Therefore, there is a knowledge gap where other interventions to reduce presenteeism need to be explored.

Pain neuroscience education (PNE) is an increasingly popular modality for managing musculoskeletal pain.17 It is an educational approach based on a biopsychosocial model that helps people change their pain-related beliefs, increase knowledge about pain, and transform their behaviors such that they perceive pain as a less threatening experience.18 A systematic review demonstrated that PNE can enhance pain reconceptualization.17 Although PNE alone is not effective enough, its benefits can increase when it is combined with exercise.19, 20 However, to date, no studies have investigated whether a combination of PNE and exercise are effective in reducing presenteeism and pain in healthcare workers.

To address this research gap, we aimed to examine whether a regimen of combined PNE and exercise tailored to individual healthcare workers was effective in reducing presenteeism.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design

We carried out a parallel-group randomized controlled trial according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Konan Women's University (ID: 2020019) and the study was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMINID: 000040122). We explained the purpose and protocol of the study to all the participants and obtained their written informed consent. Data were collected from June 2020 until December 2020.

2.2 Participants

The trial was designed to compare the effects of a therapist-designed, combined PNE and exercise program with the effects of a non-exercise, feedback-based program. We considered medical professionals including nurses, physical therapists, occupational therapists, care workers, care managers, and medical office workers as potential participants worked for the same medical corporation but in different locations. The inclusion criterion for participants was 20 years or older. We recruited the participants by flyers in the hospitals.

2.3 Randomization and blinding

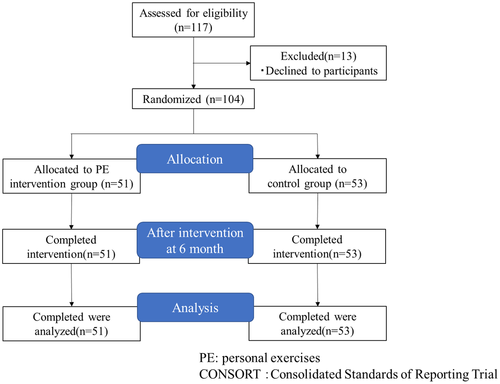

The participants were randomized into two groups, the intervention group and control group (Figure 1), using computerized random numbers by a researcher not involved in any other aspect of the study. The evaluators and data analysts were blinded to the study hypothesis and the treatment allocation. They did not receive any information regarding the design or the interventions in terms of the control or experimental group. The patients were not blinded to the treatment method owing to the nature of the intervention.

2.4 Intervention group

The Template for Intervention Description and Replication Checklist was used as a guide for the intervention description. The intervention group received a combined exercise and PNE plan created by one physical therapist (T.K.) with 10 years of experience. The primary aim of the exercises was to decrease pain and improve presenteeism. The participants were asked to perform the exercises at work and were encouraged to conduct additional interviews and work together (physical therapist) to find solutions to their health conditions. Physical elevation was recommended to improve the range of motion of the trunk, upper and lower joints (shoulder, hip, and knee). After undergoing a physical assessment, the participants commenced the exercise program, which included stretching for 20 min and walking for approximately 30 min 3–4 times a week for 6 months; the intensity of the exercises progressively increased during the intervention period (exercise intensity was moderate). Each stretch was conveniently performed as four sets of 30-s holds for each muscle group (Quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius, and trunk flexor-extensor muscles), and participants were encouraged to progress the stretch further into range over the treatment period. Participants with other painful areas were also recommended stretching exercises for the areas.

The participants were instructed to self-stretch the joint or muscle that showed reduced flexibility according to the physical therapist (neck, trunk, upper, lower limb). The therapists checked the participants twice a month to ensure treatment compliance. If the participants reported excessive pain during the exercise, the exercise was stopped or the intensity was temporarily decreased, and the physical therapist addressed the pain at the next face-to-face session.

The participants were given a pamphlet and a 20-min seminar on PNE that was developed per previously described methods.21 The PNE focused on seven sections: (1) physiology and pathways of the nervous system; (2) difference in acute and chronic pain mechanisms; (3) descending inhibition and facilitation of pain; (4) central sensitization and central sensitization syndrome; (5) environmental influences on nerve sensitivity; (6) the fear-avoidance model; and (7) methods to reduce sensitization (exercise).

2.5 Control group intervention

The control group received only feedback based the participants’ responses to a questionnaire at baseline, and they did not exercise. The feedback provided by the therapists was as follows: if the participants were feeling stressed, the therapists suggested changing their minds, or if participants were not getting exercise, the therapists suggested taking a walk. Unless there were questions, the therapists did not make any comments, and did not make comments pertaining to PNE.

2.6 Outcome measurements

All the participants filled out the Japanese version of the World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (WHO-HPQ), Central Sensitization Inventory-9 (CSI-9), Pain intensity, Widespread Pain Index (WPI), Brief Job Stress Questionnaire (BJSQ), and EuroQol 5-dimension (EQ5D-5L). A physical therapist was responsible for all outcome measurements. This assessor was blinded to the questionnaire data and to treatment allocation.

2.6.1 Primary outcomes

WHO-HPQ

The Japanese version of the WHO-HPQ was used to evaluate the absolute and relative presenteeism.22-24 It is a reliable and valid self-reported questionnaire that assesses the degree to which health problems interfere with an individual's ability to perform job tasks. Absolute presenteeism is actual performance and relative presenteeism is the ratio of actual performance to the performance of most workers in the same job.20

We phrased the question on absolute presenteeism as “On a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is the worst job performance anyone could have at your job and 10 is the performance of a top worker, how would you rate the usual performance of most workers in a job similar to yours?” and calculated it by multiplying the respondent's answer by 10. The question on relative presenteeism was “Using the same 0-to-10 scale, how would you rate your overall job performance on the days you worked during the past 4 weeks (28 days)?” Therefore, relative presenteeism = actual performance (relative presenteeism question)/the performance of most workers in the same job (absolute presenteeism question).

2.6.2 Secondary outcomes

Pain assessment

We used the Numeral Rating Scale (NRS: 0 = no pain and 10 = highest possible degree of pain) to assess pain intensity and the WPI to assess the presence of pain in 19 designated body locations over 7 days (such as left upper arm, right lower leg). Each location corresponded to a score of 1. All the items were summed to yield a total score, with higher scores indicating greater and more widespread pain.

CSI

The CSI was developed as a screening tool to identify and quantify patients with central sensitization-related symptoms.25, 26 The validity of the CSI as an assessment tool for patients with chronic pain has been demonstrated previously; the total CSI score indicates widespread pain, pain intensity, disability, quality of life (QOL), and pain catastrophizing.27

BJSQ

The Stress Check Program recommends using the BJSQ28 and proposes some criteria for defining “high-stress” workers based on the BJSQ.29 The BJSQ consists of 57 items that help to assess job stressors, such as psychological job demands and job control (17 items), psychological and physical stress reactions (29 items), and buffering factors, such as social support at work (11 items). In the present analysis, we summed the item score of the 4-point Likert scale (1 = low stress to 4 = high stress) to calculate the stress reaction and job stressor scores. For each stress reaction and job stressor, the scores ranged between 29–116 and 26–104, respectively.

EQ5D-5L

The EQ5D-5L is an instrument that standardizes various diseases and can be used as a complementary assessment for existing health-related QOL measures.30 It generates a single index value that describes the patient's health state based on their answers on a 5-point scale for each parameter. These values are expressed in numbers, ranging from 0 (dead) to 1 (full health). We used the Japanese version of the EQ5D-5 L and a Japanese scoring system has been established as valid and reliable.31

2.6.3 Sample size calculation

We calculate the sample size using the G*Power 3.1 software (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf) for Windows. A two-way mixed repeated measures ANOVA indicated that a total sample size of 74 was needed to reach 80% power, in order to detect an interaction effect size of 0.25 (medium effect) at a significance level of 0.05. Our main outcomes were available for 104 participants, which exceeded the calculated value.

2.6.4 Statistical analyses

We performed a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) using 2 (group) × 2 (assessment session) to assess the outcome measurements, and performed a post-hoc test with the SPSS ver. 26.0 software (IBM Corp.) using Bonferroni's correction. Effect sizes were calculated as partial eta squared (η2) for the ANOVA results and the significance level was set at P = .05.

3 RESULTS

We enrolled 117 participants in our study, of which 13 declined to participate (Figure 1). Therefore, we included 104 people in our analyses (intervention group = 51; control group = 53). The participants’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All participants had pain in some part of their body.

| All (n = 104) | Intervention group (n = 51) | Control group (n = 53) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 20–30 | 22 (21.2) | 8 (15.7) | 14 (26.4) |

| 31–40 | 21 (20.2) | 12 (23.5) | 9 (17.0) |

| 41–50 | 38 (36.5) | 17 (33.3) | 21 (39.6) |

| 51–60 | 17 (16.3) | 10 (19.6) | 7 (13.2) |

| 60–69 | 6 (5.8) | 4 (7.8) | 2 (3.8) |

| Sex (female: %) | 79 (76.0) | 44 (86.2) | 35 (66.0) |

| Occupational category | |||

| Nurses | 16 (15.4) | 5 (9.8) | 11 (20.8) |

| Physiotherapists or occupational therapist | 22 (26.0) | 5 (9.8) | 22 (41.5) |

| Care workers | 33 (31.7) | 17 (33.3) | 16 (30.2) |

| Care managers | 24 (23.1) | 20 (39.2) | 4 (7.5) |

| Medical office worker | 4 (3.8) | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0) |

| Absolute Presenteeism | 63.4 (13.8) | 59.8 (13.5) | 66.8 (13.3) |

| Relative Presenteeism | 0.96 (0.26) | 0.85 (0.34) | 1.06 (0.34) |

| Pain intensity | 4.2 (2.8) | 4.6 (2.6) | 3.9 (2.9) |

| CSI | 21.3 (12.3) | 22.1 (11.8) | 20.5 (12.9) |

| WPI | 3.4 (2.7) | 3.4 (3.0) | 3.4 (2.5) |

| Site of pain, n (%) | |||

| Back | 102 (98.1) | 39 (76.5) | 36 (67.9) |

| Upper limb | 18 (17.3) | 45 (88.2) | 31 (58.5) |

| Lower limb | 9 (8.6) | 26 (51.0) | 20 (37.7) |

| Back + Upper limb | 18 (17.3) | 47 (92.2) | 42 (79.2) |

| Back + Lower limb | 29 (27.9) | 46 (90.2) | 36 (67.9) |

| BJSQ | |||

| Job stress | 56.9 (7.7) | 57.7 (6.8) | 56.1 (8.5) |

| Physical and psychological stress | 55.4 (13.1) | 57.4 (13.5) | 53.5 (12.5) |

| EQ-5D | 0.83 (0.14) | 0.81 (0.15) | 0.85 (0.13) |

Note

- Data have been expressed as mean ± standard deviation or N (%).

- Abbreviations: BJSQ, brief job stress questionnaire; CSI-9, Central Sensitization Inventory-9; EQ5D-5L, EuroQol 5-dimension; WLQ, Work Limitations Questionnaire; WPI, Widespread pain index.

Table 2 presents a pre- and post-intervention comparison of our participants. In the two-way ANOVA, we found a significant group-time interaction in terms of absolute presenteeism (F = 12.87, P = .001, partial η2 = 0.94), relative presenteeism (F = 4.37, P = .04, partial η2 = 0.04), pain intensity (F = 11.0, P = .001, partial η2 = 0.1), WPI (F = 4.89, P = .03, partial η2 = 0.046), job stress (F = 7.91, P = .006, partial η2 = 0.07), and physical stress (F = 8.23, P = .005, partial η2 = 0.08) for both groups (P < .05). For the intervention group, we observed significant improvement in presenteeism, pain intensity, WPI, physical and psychological stress, and EQ5D-5L after the intervention (P < .05). In the control group, we noted a significant improvement only in job stress post intervention (P < .05). We observed significant between-group differences in presenteeism after the intervention (P < .05).

| Intervention group (n = 50) | Control group (n = 50) | F | P value | Effect size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||||

| Absolute presenteeism | 59.8 (13.5) | 66.7 (13.4)*,# | 66.8 (13.3) | 62.6 (20.1) | Interaction | 12.87 | .001 | 0.94 |

| Group | 0.32 | .57 | 0.09 | |||||

| Time | 0.78 | .38 | 0.14 | |||||

| Relative presenteeism | 0.85 (0.34) | 0.99 (0.48)*,# | 1.06 (0.34) | 1.05 (0.47) | Interaction | 4.37 | .04 | 0.54 |

| Group | 7.83 | .006* | 0.79 | |||||

| Time | 3.42 | .07 | 0.45 | |||||

| Pain intensity | 4.6 (2.6) | 3.0 (1.9)* | 3.9 (2.9) | 3.9 (2.6) | Interaction | 11.00 | .001 | 0.9 |

| Group | 0.04 | .84 | 0.06 | |||||

| Time | 11.56 | .001* | 0.92 | |||||

| CSI | 22.1 (11.8) | 19.9 (11.6) | 20.5 (12.9) | 19.5 (13.1) | Interaction | 0.48 | .49 | 0.1 |

| Group | 0.23 | .64 | 0.08 | |||||

| Time | 3.7 | .057 | 0.48 | |||||

| WPI | 3.4 (3.0) | 2.3 (2.0)* | 3.4 (2.5) | 3.3 (2.1) | Interaction | 4.89 | .03 | 0.6 |

| Group | 1.11 | .3 | 0.18 | |||||

| Time | 7.45 | .007* | 0.77 | |||||

| BJSQ | ||||||||

| Job stress | 57.7 (6.8) | 57.3 (7.0) | 56.1 (8.5) | 59.4 (9.1)* | Interaction | 7.91 | .006 | 0.8 |

| Group | 0.06 | .81 | 0.056 | |||||

| Time | 4.81 | .03* | 0.58 | |||||

| Physical and psychological stress | 57.4 (13.5) | 52.5 (11.0)* | 53.5 (12.5) | 55.0 (15.8) | Interaction | 8.23 | .005 | 0.81 |

| Group | 0.09 | .77 | 0.06 | |||||

| Time | 2.38 | .13 | 2.38 | |||||

| EQ-5D | 0.81 (0.15) | 0.9 (0.13)* | 0.85 (0.13) | 0.87 (0.14) | Interaction | 3.89 | .051 | 0.5 |

| Group | 0.12 | .91 | 0.05 | |||||

| Time | 14.3 | .0003* | 0.96 | |||||

Note

- Data have been expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

- Abbreviations: BJSQ, brief job stress questionnaire; CSI-9, Central Sensitization Inventory-9; EQ5D-5L, EuroQol 5-dimension; WLQ, Work Limitations Questionnaire; WPI, Widespread pain index.

- * Significantly different from the pre-intervention time point (P < .05).

- # Significantly difference from the control group (P < .05).

4 DISCUSSION

This study showed that healthcare workers of the intervention group who practiced a combined regimen of PNE and exercise for 6 months showed reduced presenteeism than the participants in the control group.

Exercise alone may improve absenteeism and presenteeism; for example, resistance training once a week14 or short exercises for 10 min a day, 3–4 times per week is known to reduce presenteeism,32 and yoga and stretching may also have a similar effect.33 Pereira et al.12 showed that an individualized neck-specific exercise intervention improved presenteeism in the workplace, and Justesen et al.14 found that a 1-year individualized exercise training at the workplace improved absenteeism and presenteeism. However, Blangsted et al.16 reported that office workers did not benefit from a 12-month neck-and-shoulder resistance training exercise program in the workplace and that the program did not improve absenteeism and post-intervention work ability. Considering these studies, we believed that an exercise-only training program tailored to each individual in this study could have been effective against presenteeism, but we wished to check the added positive influence of PNE as well. PNE is a cognitive-based intervention that helps individuals reconceptualize their approach to pain and changes their maladaptive belief toward it (fear of pain, catastrophizing).34 Decreased productivity among workers in pain is associated with a fear of pain34; therefore, we assumed that PNE may reprogram these fears and reduce presenteeism.

Compared to the control group, pain intensity and the number of painful body areas (calculated by the WPI) were not significantly reduced in the intervention group. Lower back or neck pain and presenteeism in office workers are known to be improved by stretching (ratio of pain reduction = 13.3%)32 and reducing the sitting time (ratio of pain reduction = 3.2%).35 However, a recent systematic review concluded that there is no strong evidence in favor of any intervention in treating or preventing lower back pain.15 Peria et al.12 used a therapist-created exercise program that included 1 weekly exercise session supervised by the therapist. This method was very similar to ours, but this approach and other previous studies only used exercise that was not supervised.14, 32, 36 Our study was different because we adopted an individualized approach, ensured therapist supervision, and combined exercise with PNE, which is known to be effective in reducing pain intensity.21 Subjects with chronic low back pain have experienced a significant reduction in pain intensity was after practicing a combined approach of PNE and exercise.37, 38 Although our study did not yield the results that we hypothesized, some improvement was indicated in the reduction of pain intensity and number of painful body areas.

Galan-Martin et al.39 showed that patients with chronic pain showed improved CSI scores after PNE, while another study showed a significant reduction in CSI scores of similar patients at 6 months.40 However, there was no significant difference in the CSI scores in our study. This could be because the CSI scores for many participants in our study were very low initially, and their average CSI score was lower than those of previous studies.39, 40

This study has some limitations. First, owing to the nature of the intervention, the patients who received it could not be blinded. Second, this study is the absence of “only exercise” group, so we could not determine whether a combination of PNE and exercise is more effective than only exercise. Third, study participants were enrolled from a single medical corporation; therefore, findings from this study cannot be generalized for other settings or populations.

5 CONCLUSION

The present study demonstrated that a combination of PNE and exercise resulted in better patient outcomes, that is, reduced presenteeism, pain intensity, physical stress, and an improved psychological state and quality of life among health care workers. Our findings will help physical therapists anticipate outcomes in their patients and will assist healthcare facilities in carrying out better employee management to ensure optimal productivity.

DECLARATIONS

Approval of the research protocol: Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Konan Women's University. Informed Consent: We explained the purpose and protocol of the study to all the participants and obtained their written informed consent. Registry and the Registration: The study (ID: 2020019) was registered in the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMINID:000040122). Animal Studies: N/A.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the patients in the Kaiseikai Medical Hospital. This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) Japan Society for the Promotion of Science [KAKENHI(20K10409)].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors developed the study concept. R.I., T.N., and T.K. designed experiments; T.K. collected the data. R.I. analyzed the data with support from T.N.; R.I. wrote the manuscript with support from T.N., A.M., K.T. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.