Clinical challenges in reducing the distress of tinnitus

Noise reduction, in conjunction with counselling and night-time broadband sound therapy, reduces the distress associated with tinnitus

Brief episodes of tinnitus are a frequently reported human experience. Tinnitus causing distress is also common, but is most frequently reported by people exposed to workplace noise. Although there is no cure for tinnitus, the study by Lewkowski and colleagues, reported in this issue of the MJA,1 identifies noise reduction as a key strategy for reducing the burden for working Australians at risk of tinnitus and the associated costs to the community.

Tinnitus, from the Latin tinnire (= to tinkle, ring), describes an auditory perception in the absence of an external acoustic stimulus. The character is of varying rudimentary sounds, like cicada chirping, static, humming, ringing, or buzzing, localised to one ear, both ears, or (most often) centrally within the head. Fluctuations in its character and intensity are often provoked by increased arousal or anxiety. Both adults and children report tinnitus. Studies from Sweden,2 England,3 the United States,4 and Australia5 indicate that most adults have experienced at least brief episodes of tinnitus, and about 10–15% have persistent tinnitus. A smaller proportion (about 0.5%) have intrusive tinnitus that disrupts sleep, thought clarity and mood, and is associated with anxiety and depression that occasionally leads to suicide.

The origins of tinnitus are an enigma. Attempts to understand tinnitus as an organ-specific disorder of the cochlea were unsuccessful. Sound deprivation experiments indicate that non-distressing tinnitus may be a normal human experience.6 Tinnitus is also experienced by congenitally deaf patients who have never heard sound, and by people without functional auditory nerves,7 suggesting that the origins of tinnitus, or at least its perception, are referrable to central auditory pathways.

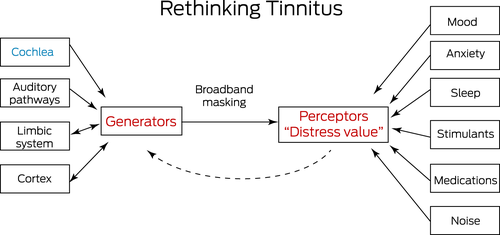

More recent neurophysiological models of tinnitus draw on knowledge of the neurophysiology of chronic pain, and are more consistent with clinical observations that fluctuations in distress for people with disturbing tinnitus parallel those in mood, anxiety, and the intake of dietary stimulants (including caffeine) (Box).8, 9 Its resistance to treatment with medications or surgery indicate that its pathophysiology is more complex than simple cochlear lesions.6 The new model is also consistent with other disorders of sensory perception, such as phantom limb pain and phantosmia (phantom smell), in which connections with limbic pathways result in unpleasant sympathomimetic responses.10

Box 1. Rethinking tinnitus: a new way of viewing tinnitus that is consistent with a neurophysiological model of “phantom sound” and clinical experience

Earlier “cochlea-centric” attempts to manage tinnitus were of limited success. Recognising modulators of tinnitus perception and using night-time masking as the basis of modern tinnitus management are far more effective in reducing tinnitus distress. Image source: adapted from an earlier article by the author.9

Although tinnitus can very occasionally be heard by other people (objective tinnitus) or an underlying diagnosis is possible (such as pulsatile tinnitus or vascular malformations), most tinnitus is subjective, and no underlying cause is found. There are no objective tests for tinnitus. Audiometry is helpful if associated hearing loss is suspected. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of auditory pathways may be indicated if the patient has unilateral tinnitus or the associated hearing loss is asymmetric.9

Many drug treatments for tinnitus have been tried, all without success. Clinical experience has shown that the most useful strategies are counselling, broadband night-time masking,11 avoiding dietary stimulants, normalising sleep patterns, mood stabilisation, and allowing time (weeks to months) for habituation to develop. Fortunately, a simple management strategy focused on these factors reduces the distress associated with tinnitus for most patients.12

As there is no cure, epidemiological studies have aimed to define who is at particular risk of tinnitus in order to facilitate preventive strategies. The study by Lewkowski and colleagues1 identified noisy occupations, ageing, hearing loss, and being male as risk factors (but not the only ones). The authors extrapolated the results of their survey to estimate that results showed one-quarter of the Australian working population (2.4 million people) have tinnitus, including 500 000 who experience it constantly. Tinnitus is thereby more prevalent in the Australian workforce than in the overall population. Its estimated prevalence was similar to that found by the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health,2 both overall (Sweden, 26%, Australia, 24.8%) and by sex (men: Sweden, 31%; Australia, 28.6%; women: Sweden, 22%; Australia, 20.7%). The prevalence of constant tinnitus was also similar in both working populations (Sweden, 7%; Australia, 5.5%), and in both countries men were more than twice as likely as women to have constant tinnitus. The prevalence of tinnitus in the Australian workforce was also similar to estimates for all adults in the United States (25.3%)13 and Poland (20.1%).14

Clinical studies of tinnitus have been hampered by the lack of validated tools for its investigation, including consistent definitions, probing surveys, and animal models. Nevertheless, the findings of Lewkowski and her colleagues1 indicate that improving working conditions in certain occupations — particularly reducing noise exposure — is likely to be helpful for reducing the burden of tinnitus. Noise reduction, in conjunction with counselling and night-time broadband sound therapy, is a simple management strategy that, given time, reduces the distress associated with tinnitus. Despite not being cured, living with tinnitus becomes a lot more comfortable.

Competing interests

No relevant disclosures.

Provenance

Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.