Evidence-based care to support longer, healthier lives for cancer survivors

Improving integrated care and systematically targeting major cancer and non-cancer causes of morbidity and mortality could yield major benefits

Cancer is the leading cause of death and disability in Australia, and it is estimated that more than 1.6 million people were living with cancer at the end of 2015.1 Most of these people will live with the disease for many years; for all cancers combined, five-year relative survival in 2012–2016 was about 69%.1 Although cancer is regarded by many people as a single condition, it is highly heterogeneous, with extreme variations in experiences and outcomes according to the type, aggressiveness, treatment, and stage of the cancer, and the age and comorbid conditions of the patient.

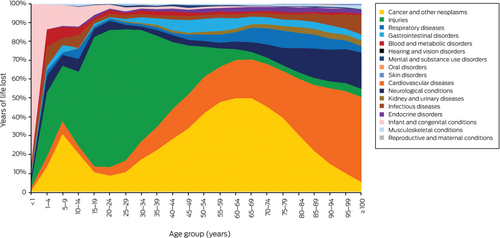

Maximising the health, wellbeing, and longevity of cancer survivors is informed by large scale evidence about long term outcomes. In this issue of the MJA, Koczwara and colleagues report mortality outcomes for the more than 32 000 people diagnosed with cancer in South Australia during 1990–1999 and still living at least five years after diagnosis.2 The authors found that this group had an estimated 24% higher risk of dying in the subsequent 12 years than people in the general population. Consistent with overseas findings,3 cancer was the most common cause of death for people with cancer; 45% of all deaths in this group were attributed to cancer. Other causes of death were important — ischaemic heart disease, stroke, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes — and their contributions increased with age and time since cancer diagnosis. The same phenomenon is observed in the general Australian population, in which the proportion of fatal burden of disease attributed to cardiovascular disease (CVD) rapidly increases with age (Box).4

Box 1. Relative proportions of years of life lost because of fatal conditions, Australia, 2015; by disease and age group

Data source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.4

This, to some extent, is what success looks like: people with cancer living long enough to die of conditions that are generally more common in later life. The higher mortality risk among long term survivors of cancer, although significant, is moderate; at the same time, major opportunities for improvement remain.

Cancer survivors have a higher risk of CVD than the general population2, 5 and those diagnosed with cancers with good prognoses often die of CVD rather than because of cancer recurrence or progression.3, 6 While the cardiotoxicity of certain types of cancer chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiotherapy is recognised, other factors that increase CVD risk in cancer survivors are often underappreciated. Like people without cancer,7 cancer survivors have an appreciable background CVD risk. Many types of cancer and CVD share risk factors, such as smoking and obesity, and cancer itself increases CVD risk, especially that of venous thrombo-embolism.5 Finally, focusing on cancer and its treatment can lead to suboptimal CVD preventive care.8

What, then, are the implications of the evidence regarding late mortality for cancer survivors and people caring for those with cancer? It is reassuring that mortality outcomes for many long term survivors gradually approach those of the general population. This underscores the importance of integrated, holistic, and tailored long term care, particularly primary care, for cancer survivors, including care for reducing cancer progression and recurrence, balanced by prevention and management of the patient’s other, often overlooked conditions.8

A key strategy for cancer survivorship is ensuring that best practice support for smoking cessation is consistently and universally provided. Smoking leads to large increases in all-cause mortality, including among people with cancer, and increases mortality attributable to many cancers9 and to four of the five other leading causes of death identified by Koczwara and his colleagues.2 While many smokers with cancer quit successfully, most continue to smoke after diagnosis.10

As many as 80% of CVD events can be prevented,11, 12 and Australian guidelines recommend health behaviour changes and pharmacotherapy tailored to a person’s level of absolute risk.13 However, more than half the people with existing CVD and more than 75% of the general Australian population at high risk of CVD do not receive recommended blood pressure- and lipid-lowering preventive therapies.7 Despite higher CVD risks, the uptake of CVD preventive pharmacological and lifestyle treatments by people with cancer is low, and is similar to or lower than uptake by the general population.14

Ensuring that the CVD risk of cancer survivors is systematically assessed and managed according to best practice could substantially improve their outcomes. While no specific modification of CVD risk algorithms for cancer survivors is currently recommended, clinical judgement can be applied to tailoring preventive interventions for people at particularly high risk of CVD.13

Improvements in cancer survival are a tribute to efforts across the entire health system, from prevention and early detection to treatment and long term primary care. Improvements in integrated care that systematically target major cancer and non-cancer causes of morbidity and mortality could yield even greater benefits.

Acknowledgements

Emily Banks is supported by a Principal Research Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Competing interests

No relevant disclosures.

Provenance

Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.