Demographic Parameters of Golden Spotted Rock Bass Paralabrax auroguttatus from the Northern Gulf of California

Abstract

The sex ratios, growth, and mortality of the golden spotted rock bass Paralabrax auroguttatus (Serranidae) were determined for populations from Islas Encantadas and Bahía de los Angeles in the Gulf of California. Specimens ranged from 137 to 479 mm standard length and from 135 to 3,100 g. Sagittal otoliths were used to determine age. A von Bertalanffy model of growth for both populations combined was estimated as Lt = 474.4·(1 − e−0.115(t+ 2.093)), where Lt is fish length at age t. This model is comparable to those for other rock basses. The relationship between length and weight (W) followed the power function W = 0.00002·L3.0797 (r2 = 0.96) with no difference between males and females. The mortality rate was estimated as 49% per year for fish of age 5 and older. In our Bahía de los Angeles samples, the sex ratio was significantly skewed, with more males than females. The mean size of females was significantly smaller at Bahía de los Angeles than in Islas Encantadas. Examination of the sex ratios for these two populations suggested that this species is gonochoristic.

Introduction

The rock bass genus, Paralabrax, is composed of nine species, eight of which reside in the eastern Pacific Ocean from California to Chile, including one species endemic to the Galápagos Islands and one from the western Atlantic Ocean (Meisler 1987; Grove and Lavenberg 1997). Considered the most temperate representatives of the serranid family, these basses are dominant nearshore rocky-reef predators and are important economically. The three southern California species, kelp bass P. clathratus, barred sand bass P. nebulifer, and spotted sand bass P. maculatofasciatus, have been intensively studied with respect to their fishery potential owing to the collapse and eventual closure of the commercial fishery (Collyer and Young 1953; Young 1963; Ono 1992; Read 1992). In the last 50 years, these fishes have recovered enough to become the mainstay of a multimillion-dollar sportfishing industry with approximately 1,000,000 fish being taken annually (Read 1992). Their ecological and commercial importance has motivated life history studies (Quast 1968; Love and Ebeling 1978; Allen et al. 1995; Love et al. 1996), including extensive juvenile recruitment surveys (Carr 1994; Pondella and Stephens 1994; Cordes and Allen 1997) and reproduction studies (Smith and Young 1966; Hastings 1989; Oda et al. 1993; Allen et al. 1995; Hovey and Allen 2000).

In contrast, the golden spotted rock bass Paralabrax auroguttatus has received comparatively little study. This species is found from Isla Cedros to Cabo San Lucas along the Pacific coast of Baja California and is abundant throughout the Gulf of California (Thomson et al. 2000). As adults, these high-level carnivores can be reliably caught around high-relief rocky reefs from a depth of 25 to 155 m (Fitch and Schultz 1978; D. Pondella and L. Allen, personal observations). This species supports a viable gill-net and handline fishery in the Gulf of California and is extremely valuable from both the ecological and sportfishing standpoints (Fitch and Schultz 1978). Considering this and the fact that there is only anecdotal information about golden spotted rock bass in the literature, we conducted an investigation into the sex ratio, growth, and survival of this species.

Methods

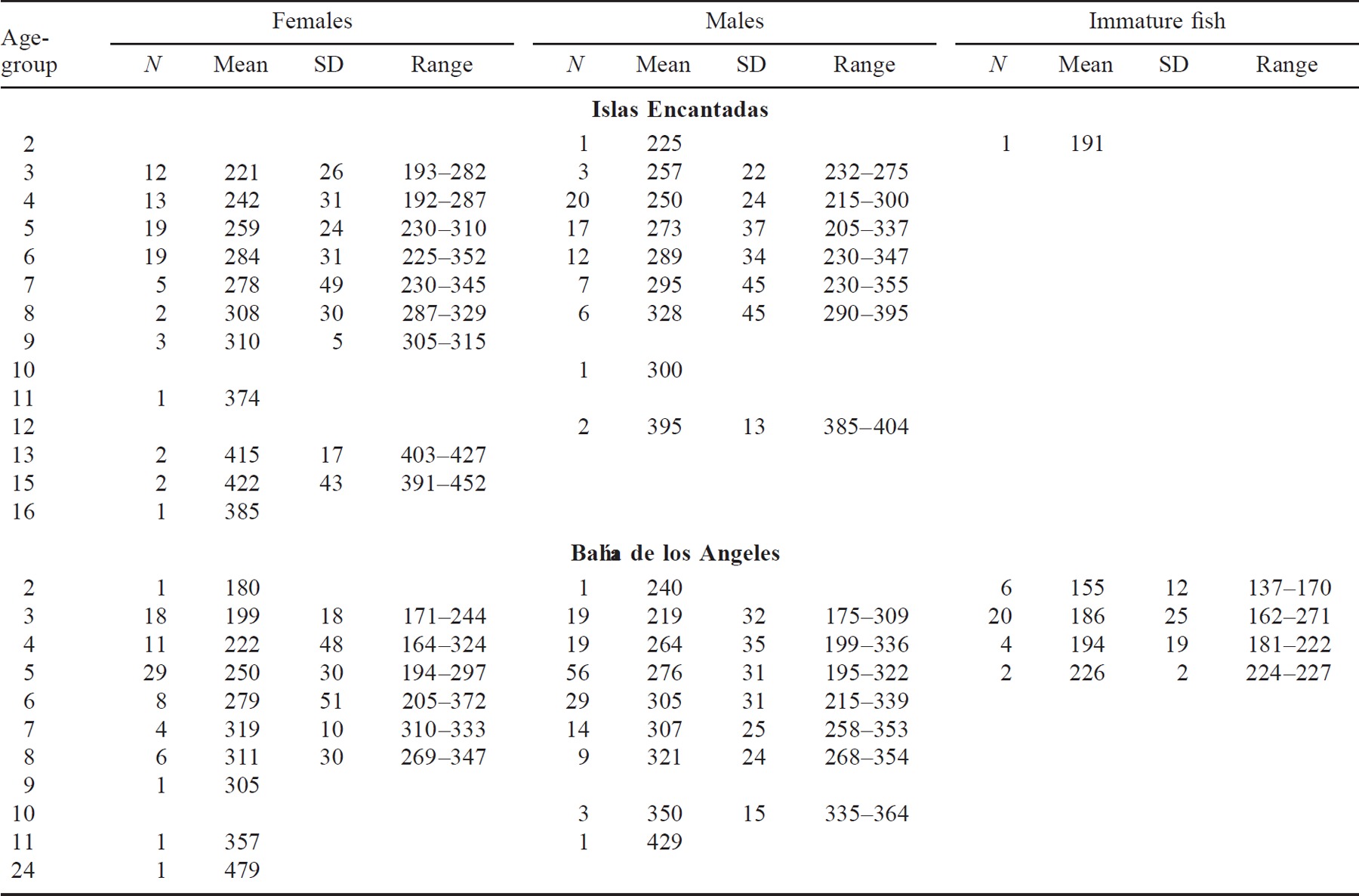

We collected golden spotted rock bass by hook and line at two times and locations within the Gulf of California: (1) from March 29 to March 31, 1994, at Islas Encantadas (N = 152), primarily on the pinnacles and seamounts surrounding Isla San Luís (29°59‘N, 114°35‘W) and (2) from March 26 to March 30, 1995, at Bahía de los Angeles (N = 240), where fish were captured primarily along the volcanic slopes of Isla Smith (29°5‘N, 113°29‘W). At both locations fish were caught at depths between 25 and 60 m. Twenty-eight specimens were also obtained from commercial fishermen on August 1, 1995, at Bahía de los Angeles. The hook-and-line sampling regime was consistent between locales and targeted adult fish, except at Bahía de los Angeles where we caught smaller individuals using smaller hooks. Lengths to the nearest millimeter and weights to the nearest gram were taken in the field. Sex was determined and sagittal otoliths were removed.

Following the procedures of Allen et al. (1995), sagittal otoliths (N = 421) were mounted on wood blocks with cyanoacrylate and sectioned with a Buehler Isomet low-speed saw. Sections were placed on a black background under water and read twice. If concordance was found between the first two readings, this value was accepted. Otherwise, another reader took a third reading and agreement was attempted. We could not satisfactorily age nine individuals, which were excluded from the age analysis. Age verification was not attempted, as the formation of annuli in this family is very straightforward (e.g., Bullock et al. 1992; Sadovy and Severin 1994; Allen et al. 1995; Potts and Manooch 1995; Love et al. 1996; Craig et al. 1999). Lengths at age were modeled by means of the von Bertalanffy growth equation, Lt = L∞(1 − e–k(t–t0)), using nonlinear regression analysis with Marquardt's algorithm (SPSS Inc., ver. 8.0); in this equation, Lt is standard length at time t (years), L∞ is the theoretical asymptote of Lt, k is the growth coefficient, and t0 is the time (years) when length is theoretically equal to zero (von Bertalanffy 1957). The growth curves for males and females by location were tested against each other by means of the likelihood ratio test (Kimura 1980).

Age frequencies for the two study sites were back-calculated using the age and date of capture and then compared by means of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Pooled year-class data were assembled as a catch curve, and the descending limb was modeled to describe mortality (1 − the survival rate, S; Ricker 1975). The ratios of males to females were tested for goodness of fit using the chi-square distribution based on Šidák's multiplicative inequality for three comparisons (k = 3). First, both populations were tested against an extrinsic hypothesis of a 50% sex ratio. Then a test between the two populations with the frequency of Islas Encantadas populations held as the expected frequency was performed (Sokal and Rohlf 1995). Length–weight relationships for each sex were determined using a power function (Microsoft, Excel, version 7.0) transformation. The length−weight relationships of males and females were compared by means of analysis of covariance (ANCOVA; Sokal and Rohlf 1995). This was done using covariates from the multiple regression results in the ANOVA–MANOVA package of Stat Soft's STATISTICA for Windows (release 5.1). Descriptive statistics, the Shapiro–Wilk W-statistic for normality, ANOVA, and linear regression results were also obtained with STATISTICA. Data were log transformed to ensure homoscedasticity and normality prior to the ANOVA (Legendre and Legendre 1998). In the case of multiple comparisons (k), α was adjusted by means of the Bonferroni method (α′ = α/k; Sokal and Rohlf 1995) to avoid a type I error associated with the experimentwise error rate.

Results

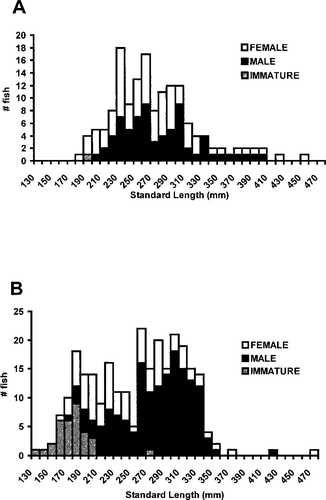

Over both sites, fish (N = 421) ranged from 137 to 479 mm standard length (SL) and from 135 to 3,100 g; 53.7% were males (N = 226), 38.2% were females (N = 161), and 8.1% were immature (N = 34). At the Bahía de los Angeles site, 66.1% (N = 156) of mature fish were male, and this ratio was significantly different from both a 50:50 sex ratio (χ2 = 24.475, P < 0.05) and that at Islas Encantadas (χ2 = 105.669, P < 0.01) (Table 1; Figure 1). The male-biased sex ratio was especially evident in fish greater than 260 mm SL; 77.2% of the mature fish (N = 149) were male. A skewed sex ratio was not found at Islas Encantadas (χ2 = 0.801, P > 0.10; Figure 1). There was a significant difference in mean size when comparing sexes among populations (ANOVA; P < 0.000001); females in the Bahía de los Angeles population were significantly smaller than males (Student's t[234] = −5.207, P < 0.000001). The population of Islas Encantadas was normally distributed (log-transformed Shapiro−Wilk W = 0.975, P = 0.1621), while the Bahía de los Angeles population was not (Shapiro−Wilk W = 0.965, P < 0.0002). This departure from normality was driven by the truncation of the distribution at size-classes above 340 mm SL.

Standard lengths and sexual status of fish (N = 240) captured at Bahía de los Angeles March 26−30 and August 1, 1995. The mean (±SD) lengths for males and females were 281.2 ± 43.7 mm and 249.5 ± 56.4 mm), respectively. Panel (B) shows the standard lengths and sexual status of fish (N = 152) captured at Islas Encantadas March 29–31, 1994. The mean (±SD) lengths for males and females were 279.8 ± 45.3 mm and 271.0 mm ± 43.67 mm, respectively

The relationships of whole fish weight (w) to length (SL) followed the function logew = a + b·logeSL. Estimation of these relationships for males and females resulted in two lines with the same y-intercept (b = 10.8) that were not significantly different from each other (ANCOVA; P < 0.000001). The following weight−length relationship was found logew = −4.699 + 3.080logeSL (r2 = 0.96). The relationships between total length (TL) and SL were TL = 1.2286·SL + 2.9591 and SL = 0.803·TL + 0.7603, respectively (N = 34, r2 = 0.99).

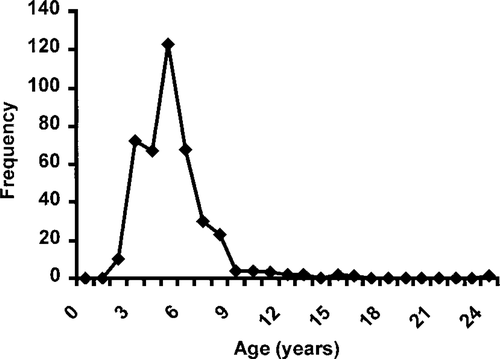

We were able to resolve the ages of 97.9% (N = 412) of the specimens. The six oldest fish were females, with a maximum age of 24 years. Overall, 95.2% (N = 393) of the fish were age 8 or less (Table 1). There were very few fish with a birth date prior to 1987. The year-class distributions for each study site were not significantly different from each other (ANOVA; P = 0.348). Thus, a pooled catch curve was used to estimate mortality (Figure 2). For fish of age 3 and above, total annual mortality (1 − S) was calculated as 0.16 (r2 = 0.86). However, the model explains more of the variance when applied to ages 5 and above (1 − S = 0.49, r2 = 0.98). At age 5, fish averaged 266 mm SL, which is a marketable size.

Age frequencies for all fish captured at Bahía de los Angeles and Islas Encantadas

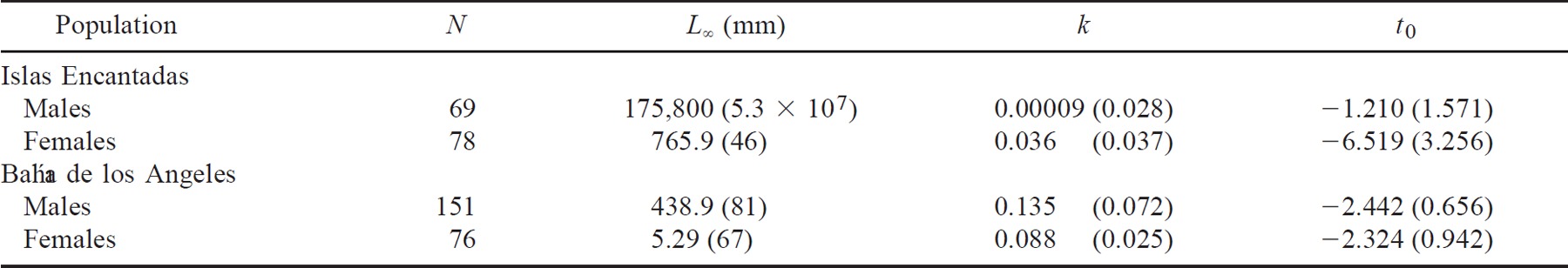

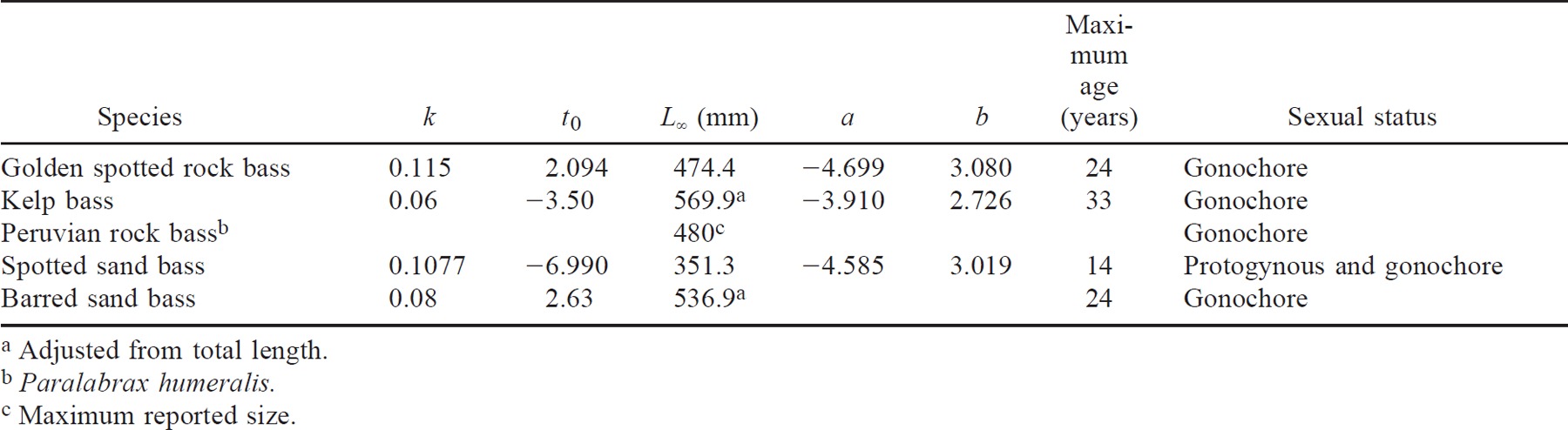

The von Bertalanffy growth model was applied to males and females at each site (Table 2). With the three model parameters constrained, the likelihood ratio test indicated that there was a significant difference (P < 0.001) between male and female growth at both locations (Kimura 1980). The estimated growth curves probably differ from each other owing to the lack of samples for larger size-classes (Table 1). For instance, males show nearly linear growth at Islas Encantadas. An overall growth curve was estimated for comparisons with other rock bass species (Table 3).

Discussion

The von Bertalanffy growth model that we estimated shows a growth pattern similar to that of other rock basses (Table 3). The calculated value for L∞ (474.42 mm SL) is nearly identical to the maximum size (479 mm SL) reported for golden spotted rock bass and falls between the values reported for spotted sand bass (351.3 mm SL) and kelp and barred sand bass (569.9 mm and 536.9 mm, respectively). However, our maximum size adjusted to total length was 119 mm shorter than the reported maximum size (Fitch and Schultz 1978). This means that the growth model's prediction of L∞ may be low. Possible reasons for this are (1) that the maximum size was reported from the Pacific coast of Baja California and it is not indicative of the sizes reached in the gulf and (2) that small sample sizes in the older size-classes led to the underestimation of L∞.

Of those fish whose sex could be determined (N = 379), 42% were female. This sex ratio is stable across the four to eight year-classes for which we have good sample sizes. After age 8 there was not much confidence in the sex structure of the population because of the small sample sizes. Coupling this information with sex by size frequency (Table 1), we found that although there were more males, males and females were distributed uniformly at all size-classes. Further, the length–weight relationships for males and females were identical. These findings are consistent with those that have been reported for other gonochoristic rock basses and suggest that golden spotted rock bass are gonochores (Smith and Young 1966; Bórquez et al. 1988; Love et al. 1996).

Fishing pressure has been shown to skew sex ratios in protogynous groupers (Hood and Schlieder 1992; Coleman et al. 1996; McGovern et al. 1998) and gonochores (Zhao and McGovern 1997; Zhao et al. 1997). In these studies, it was the proportion of males that decreased, the opposite of what we observed. At the Bahía de los Angeles site there was a significant reduction in the number and size of females. The skew in the ratio of males to females was most evident at size-classes above the minimum marketable lengths, which is a further indication of fishing pressure. This, plus a truncation of the larger size- and age-classes, increased mortality at marketable sizes, and an estimated L∞ below the maximum reported size, are all indications that the demography of these stocks may be impacted by fishing.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by the cooperation and support of the Nearshore Marine Fish Research Program, California State University, Northridge; the Vantuna Research Group at the Moore Laboratory of Zoology, Occidental College; and Grupo de Ecología Pesquera, Departmento de Ecología, Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico. Chevron Products Company also supported this research; in this regard, we want to thank Wayne Ishimoto. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the Southern California Marine Institute, and AA Lures, who provided some of the fishing tackle. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers and the following persons for their assistance on this project: Allen Andrews, Cheryl Baca, Matthew Craig, Jim Cvitanovich, Greg Tranah, and Danny Warren.