The prognostic value of integration of pretreatment serum amyloid A (SAA)–EBV DNA (S-D) grade in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma

Abstract

Background

Serum amyloid A (SAA) has been associated with the development and prognosis of cancer. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the predictive value of integration of pretreatment SAA–EBV DNA (S-D) grade and comparison with the TNM staging system in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC). The S-D grade was calculated based on the cut-off values of serum SAA and EBV DNA copy numbers which were determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. We evaluated the prognostic value of pretreatment SAA, EBV DNA and S-D grade on overall survival (OS) of NPC patients. We also evaluated the predictive power of S-D grade with TNM staging system using 4 indices: concordance statistics (C-index), time-dependent ROC (ROCt) curve, net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI).

Results

A total of 304 NPC patients were enrolled in this study. Multivariate analysis showed that TNM stage (P = 0.007), SAA (P = 0.013), and EBV DNA (P = 0.033) were independent prognostic factors in NPC. The S-D grade was divided into S-D grade 1, S-D grade 2, and S-D grade 3, which had more predictive accuracy for OS than TNM staging according to all 4 indices.

Conclusions

We found that the S-D grade could be used as a new tool to predict the OS in NPC patients.

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is one of the most common malignant tumors in Southern China and Southeast Asia, with an incidence rate of 2.8 in 100,000 people per year in men and 1.9 in 100,000 people per year in women [1]. Patients diagnosed with early NPC (stages I–II) have excellent outcomes, with 5-year survival rates of up to 94%, but patients diagnosed with NPC in stages III–IV have a poorer prognosis, whith 5-year survival rates lower than 80% [2]. Currently, the general standard for predicting prognosis and facilitating treatment stratification of NPC patients is the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer/American Joint Cancer Committee (UICC/AJCC) TNM staging system [3, 4]. This staging system only focuses on the tumor size, extension and node involvement, and does not consider other prognostic factors (clinicopathologic features, treatment- related factors, inflammatory state). As a result, the NPC patients with similar histologic classifications and stages often have very different survival outcomes, identifying need for a more precise method to improve the prediction of NPC patient outcomes.

Chronic inflammation is a key contributor to cancer initiation, promotion, progression, and metastasis [5]. Serum amyloid A (SAA) is a nonspecific, acute-phase, hepatic protein secreted in response to cytokines [6]. It is also an HDL-associated lipoprotein known to play a major role as a modulator of inflammation and in the metabolism and transport of cholesterol [7]. Of interest, SAA has been reported as a potentially prognostic biomarker in many cancers including renal cancer, lung cancer, melanoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [8-13]. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection plays an important role in NPC pathogenesis [14]. The plasma EBV DNA assay is widely used for screening, prognostic prediction, and post-treatment surveillance of patients with NPC [15].

At present, no published studies have combined SAA and EBV DNA as predictive markers for overall survival in NPC patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the prognostic value of integration of pretreatment SAA–EBV DNA (S-D) grade in NPC patients. These results will provide a simple and precise prognostic tool to predicting survival in NPC patients.

Methods

Patients and study design

We performed a retrospective analysis of NPC patients were treated at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, China) between December 2008 and December 2011. Patients were enrolled in this study if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) NPC diagnosis confirmed by histopathology, no other malignancies; (2) data were obtained prior to anti-tumor treatment; (3) complete baseline clinical information and laboratory data; (4) complete follow-up data; (5) death resulting from cancer-specific death.

Clinical data were collected from medical records prior to anti-tumor treatment, including age, gender, TNM stage, therapeutic data, C-reactive protein (CRP), Serum amyloid A (SAA) level, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), and EBV DNA copy number. Clinical stage was classified according to the 7th TNM classification of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual [16].

All patients provided written informed consent for enrollment in this research study. This study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee in Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in China. The authenticity of this article has been validated by uploading the key raw data onto the Research Data Deposit public platform (http://www.researchdata.org.cn), with the approval RDD number as RDDA2019001145.

Clinical outcome assessment and patient follow-up

The patients were followed-up by telephone, letter, or at an outpatient interview. Our endpoint was cancer-specific overall survival (OS), which was defined as the interval between the date of NPC diagnosis to the date of death due to malignancy, or by patient censoring on the date of last follow-up. All patients were followed until death or until August 2015 (end of study).

Construction of SAA–EBV DNA (S-D) grade

According to the Youden index by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, the cut-point for SAA was 4.46 mg/L, and for EBV DNA was 2340 copies/mL. Based on these cut-off values, the prognostic value of S-D grade was defined as follows: S-D grade 1: patients with both a SAA level ≤ 4.46 mg/L and EBV DNA ≤ 2340 copies/mL; S-D grade 2: if either of the two markers were elevated; S-D grade 3: patients with both markers elevated.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R version 3.6.0. Categorical variables were stratified by clinical application, and the optimum cut-off points of continuous variables for predicting the overall survival (OS) were determined by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) method and compared using log-rank test. Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were entered into Cox proportional hazards analyses. Independent prognostic factors were determined with multivariate Cox analyses (P < 0.05). The discrimination ability of SAA, EBV DNA, S-D grade and TNM staging system to predict survival were measured by Harrell's [17] concordance index (C-index), time-dependent receiver operative characteristics (ROCt) [18], net reclassification index (NRI) [19] and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) [19]. The C-index was defined as the proportion of patient pairs in which the predicted and observed survival outcomes were concordant. Time-dependent ROC (ROCt) curves by plotting sensitivity versus specificity, and areas under the curve (AUC) were calculated to estimate the predictive accuracy. The NRI was a new statistical method to measure the improvement in predictive performance of a new model to re-classify subjects compared to an old model into binary event or no-event categories [20]. The NRI assigned a numerical score of + 1 for upward reclassification, − 1 for downward and 0 for subjects who were not reclassified. Individual scores were summed separately for the event and non-event groups, and divided by numbers of subjects in each group. The IDI was computed based on integrated sensitivity and specificity which can be defined as a difference in discrimination slope between an existing model and a new model [21]. If the IDI > 0, this indicated that the new model had better prediction ability than the old model. If the IDI < 0, it was negative improvement, and the new model's prediction ability was less than the old model. If IDI = 0, both models were able to predict survival with equal strength. Overall, larger values for the C-index, AUC, NRI and IDI indicated more accurate prognostic stratification. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses performed.

Results

Patient characteristics and cutoff Values of continuous variables

The clinicopathologic characteristics of patients were shown in Table 1. A total of 304 patients with a pathological diagnosis of NPC were enrolled in this study, with 232 (76.3%) male and 72 (23.7%) female patients. The median age was 46 years (range, 17–78 years), with a median follow-up time of 44.4 months (range 0.7–76).

Patient characteristics |

No. of patients (%) |

Median OS (IQR) |

P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

Gender |

|||

Male |

232 (76.3%) |

44.2 (38.5–47.4) |

0.967 |

Female |

72 (23.7%) |

44.8 (40.7–46.8) |

|

Age (years) |

|||

≤46 |

157 (51.6%) |

45.0 (40.6–47.8) |

0.202 |

> 46 |

147 (48.4%) |

43.4 (37.2–46.8) |

|

Tumor stage |

|||

T1–2 |

52 (17.1%) |

46.2 (41.9–49.8) |

0.043 |

T3–4 |

252 (82.9%) |

44.0 (38.3–46.9) |

|

Node stage |

|||

N0–1 |

168 (55.3%) |

44.5 (40.8–47.0) |

0.007 |

N2–3 |

136 (44.7%) |

43.9 (36.0–47.8) |

|

TNM stageb |

|||

I–II |

33 (10.9%) |

45.8 (41.3–48.0) |

0.048 |

III–IV |

271 (89.1%) |

44.2 (39.2–47.1) |

|

Treatment |

|||

Radiotherapy |

43 (14.1%) |

44.0 (40.7–48.1) |

0.047 |

Chemoradiotherapy |

261 (85.9%) |

44.4 (38.7–47.0) |

|

CRP (mg/L) |

|||

≤ 2.03 |

131 (43.1%) |

44.6 (41.9–47.4) |

0.001 |

> 2.03 |

173 (56.9%) |

44.1 (36.0–47.0) |

|

SAA (mg/L) |

|||

≤ 4.46 |

154 (50.7%) |

44.7 (41.7–47.4) |

0.001 |

> 4.46 |

150 (49.3%) |

43.3 (35.2–47.1) |

|

PLR |

|||

≤ 141.52 |

167 (54.9%) |

44.0 (40.1–47.0) |

0.287 |

> 141.52 |

137 (45.1%) |

45.1 (37.2–47.5) |

|

NLR |

|||

≤ 2.62 |

149 (49.0%) |

44.2 (40.6–47.5) |

0.006 |

> 2.62 |

155 (51.0%) |

44.5 (36.1–47.0) |

|

LMR |

|||

≤ 1.87 |

29 (9.5%) |

45.3 (42.1–50.3) |

0.415 |

> 1.87 |

275 (90.5%) |

44.2 (39.2–47.0) |

|

EBV DNA (copies/mL) |

|||

≤ 2340 |

161 (53.0%) |

45.0 (40.9–47.6) |

<0.001 |

> 2340 |

143 (47.0%) |

43.4 (36.0–46.4) |

|

- a Survival was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier method and compared with Log-Rank test;

- b TNM stage was classified according to the AJCC 7th TNM staging system; IQR interquartile range, TNM tumor node metastasis stage, CRP C-reactive protein, SAA serum amyloid A, PLR platelet/lymphocyte ratio, NLR neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, LMR ymphocyte/monocyte ratio, EBV Epstein-Barr virus

According to the ROC curves, the optimal cut-off points for age, CRP, SAA, PLR, NLR, LMR, and EBV DNA were 46, 2.03, 4.46, 141.52, 2.62, 1.87, and 2340, respectively.

Univariate and multivariate survival analysis

The results of the univariate and multivariate analysis for OS were shown in Table 2. Univariate analysis demonstrated that node stage (P = 0.008), TNM stage (P < 0.001), CRP (P = 0.002), SAA (P = 0.001), and EBV DNA (P = 0.01) were prognostic factors in NPC patients. Multivariate Cox-analysis showed that TNM stage [hazard ratio (HR): 2.190, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.234–3.866, P = 0.007), SAA (HR: 2.276, 95% CI 1.186–4.368, P = 0.013), and EBV DNA copy number (HR: 2.075, 95% CI 1.061–4.060, P = 0.033) were independent prognostic factors in these patients.

Variables |

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysisa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

HR |

95.0% CI for HR |

P value |

HR |

95.0% CI for HR |

P-value |

|

Gender |

||||||

Male vs female |

1.014 |

0.515–1.997 |

0.967 |

– |

– |

– |

Age |

||||||

≤46 years vs > 46 years |

1.458 |

0.814–2.612 |

0.205 |

– |

– |

– |

Tumor stage |

||||||

T1–2 vs T3–4 |

3.17 |

0.976–10.144 |

0.055 |

– |

– |

– |

Node stage |

||||||

N0–1 vs N2–3 |

1.497 |

1.110–2.020 |

0.008 |

– |

– |

– |

TNM stage |

||||||

I vs II vs III vs IV |

2.971 |

1.709–5.165 |

<0.001 |

2.190 |

1.234–3.886 |

0.007 |

Treatment |

||||||

Radiotherapy vs chemoradiotherapy |

3.800 |

0.921–15.674 |

0.065 |

– |

– |

– |

CRP (mg/L) |

||||||

≤ 2.03 vs > 2.03 |

3.014 |

1.496–6.074 |

0.002 |

– |

– |

– |

SAA (mg/L) |

||||||

≤ 4.46 vs > 4.46 |

2.956 |

1.555–5.617 |

0.001 |

2.276 |

1.186–4.368 |

0.013 |

PLR |

||||||

≤ 141.52 vs > 141.52 |

1.368 |

0.767–2.440 |

0.289 |

– |

– |

– |

NLR |

||||||

≤ 2.62 vs > 2.62 |

2.361 |

1.260–4.426 |

0.007 |

– |

– |

– |

LMR |

||||||

≤ 1.87 vs > 1.87 |

1.619 |

0.502–5.219 |

0.420 |

– |

– |

– |

EBV DNA (copies/mL) |

||||||

≤ 2340 vs > 2340 |

3.079 |

1.620–5.851 |

0.001 |

2.075 |

1.061–4.060 |

0.033 |

- a Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate analysis (Node stage, TNM stage, CRP, SAA, NLR, and EBV DNA) were entered into multivariate analysis

Survival Analysis of SAA, EBV DNA, and S-D grade

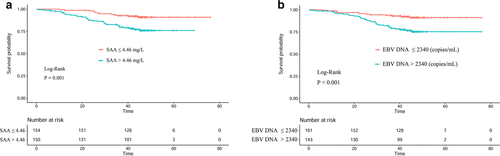

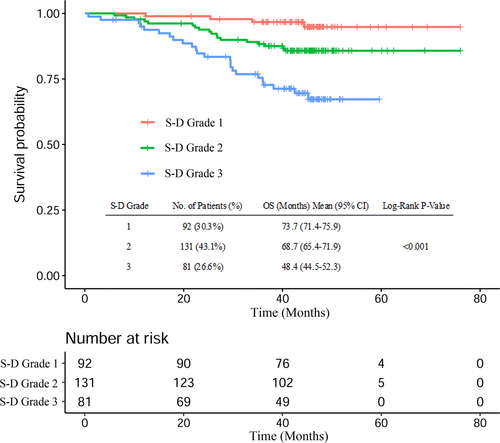

Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated that the survival of patients was significantly different when SAA (P = 0.001, Fig. 1a) or EBV DNA (P < 0.001, Fig. 1b) was used. For the patients with S-D grade 1, the median survival time was 45.2 (IQR: 41.7–47.6) months, which was higher than the S-D grade 2 (44.6 months, IQR: 40.3–47.3) and S-D grade 3 (48.4 months, IQR: 29.5–46.9). The OS of patients with S-D grade 1 was also higher than those with S-D grade 2 or S-D grade 3 (P < 0.001, Fig. 2).

Kaplan–Meier curves of SAA and EBV DNA for OS in NPC patients

Kaplan–Meier curves of S-D grade for OS in NPC patients

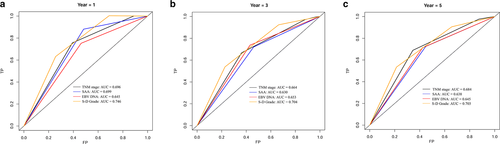

Comparison of prognostic accuracy of SAA, EBV DNA, S-D grade and TNM stage using c-index and time-dependent ROC analysis

The C-index for SAA, EBV DNA, S-D grade and TNM stage was 0.631, 0.633, 0.689 and 0.656, respectively (Table 3). The S-D grade showed increasing prognostic accuracy compared with TNM stage, but there was no statistically significant differences between these two classifiers. Results for time-dependent ROC analysis showed similar findings for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival, with the AUC of S-D grade has the highest among the four assessment methods (Fig. 3). These results indicated that the S-D grade can better predict outcomes than TNM stage.

Factors |

C-index (95% CI) |

△C-indexa |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

SAA |

0.631 (0.565–0.696) |

||

EBV DNA |

0.633 (0.566–0.700) |

||

S-D grade |

0.689 (0.623–0.754) |

||

TNM stage |

0.656 (0.590–0.723) |

||

S-D grade vs SAA |

0.058 |

0.062 |

|

S-D grade vs EBV DNA |

0.056 |

0.030 |

|

SAA vs TNM stage |

− 0.025 |

0.568 |

|

EBV DNA vs TNM stage |

− 0.023 |

0.530 |

|

S-D grade vs TNM stage |

0.032 |

0.441 |

- Statistic indicate the changes in C statistic C-index concordance index, CI confidence interval, S-D grade SAA-EBV DNA grade

Time-dependent ROC analysis of TNM stage, SAA, EBV DNA, and S-D grade for 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS in NPC patients

Comparison of discriminatory ability of SAA, EBV DNA, S-D grade and TNM stage using NRI and IDI

Results for NRI and IDI analyses at 1-, 3- and 5-year using the SAA, EBV DNA, S-D grade and TNM staging system were shown in Table 4. For NRI at 1-, 3- and 5-year survival, the discriminatory ability of S-D grade was increased 12.4%, 9.6% and 11.6%, respectively (P > 0.05), compared with TNM stage. For 1-, 3- and 5-year survival, the discriminatory ability of S-D grade was increased 0.4%, 1.8% and 3.8%, respectively (P > 0.05) compared to IDI. These results indicated that the S-D grade had superior discriminatory ability to predict survival over the TNM stage.

1-Year |

3-Year |

5-Year |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NRI |

P |

IDI |

P |

NRI |

P |

IDI |

P |

NRI |

P |

IDI |

P |

|

SAA vs TNM stage |

− 4.8% |

0.641 |

− 0.1% |

0.827 |

− 3.3% |

0.689 |

− 1.4% |

0.635 |

− 17.2% |

0.515 |

− 3.5% |

0.549 |

EBV DNA vs TNM stage |

− 15.6% |

0.482 |

− 0.4% |

0.541 |

− 5.3% |

0.549 |

− 0.8% |

0.723 |

− 12.5% |

0.615 |

− 1.4% |

0.771 |

S-D grade vs TNM stage |

12.4% |

0.472 |

0.4% |

0.589 |

9.6% |

0.348 |

1.8% |

0.571 |

11.6% |

0.537 |

3.8% |

0.470 |

- NRI or IDI > 0, it was positive improvement, this indicated that the new model had better prediction ability than the old model. If NRI or IDI < 0, it was negative improvement, and the new model's prediction ability was less than the old model. If NRI or IDI = 0, it was considered the new model had not changed

Relationship between SAA, EBV DNA, S-D grade and clinicopathological features

The association between the SAA, EBV DNA, S-D grade and clinicopathologic characteristics were shown in Table 5. Our results demonstrated that each of the SAA, EBV DNA and S-D grade was positively correlated with the node stage (P < 0.05), TNM stage (P < 0.05) and treatment (P < 0.05).

Variables |

SAA (mg/L) |

EBV DNA (copies/mL) |

S-D Grade |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

≤ 4.46 (n = 154) |

> 4.46 (n = 150) |

P |

≤ 2340 (n = 161) |

> 2340 (n = 143) |

P |

1 (n = 92) |

2 (n = 131) |

3 (n = 81) |

P |

|

Gender |

||||||||||

Male |

114 |

118 |

0.349 |

123 |

109 |

1.000 |

70 |

97 |

65 |

0.586 |

Female |

40 |

32 |

38 |

34 |

22 |

34 |

16 |

|||

Age (years) |

||||||||||

≤ 46 |

76 |

81 |

0.424 |

80 |

77 |

0.492 |

46 |

64 |

47 |

0.401 |

> 46 |

78 |

69 |

81 |

66 |

46 |

67 |

34 |

|||

Tumor stage |

||||||||||

T1–2 |

32 |

20 |

0.095 |

34 |

18 |

0.066 |

22 |

22 |

8 |

0.050 |

T3–4 |

122 |

130 |

127 |

125 |

70 |

109 |

73 |

|||

Node stage |

||||||||||

N0–1 |

95 |

73 |

0.028 |

118 |

50 |

<0.001 |

66 |

81 |

21 |

<0.001 |

N2–3 |

59 |

77 |

43 |

93 |

26 |

50 |

60 |

|||

TNM stage |

||||||||||

I |

5 |

3 |

0.016 |

7 |

1 |

<0.001 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

<0.001 |

II |

18 |

7 |

18 |

7 |

13 |

10 |

2 |

|||

III |

81 |

68 |

94 |

55 |

52 |

71 |

26 |

|||

IV |

50 |

72 |

42 |

80 |

22 |

48 |

52 |

|||

Treatment |

||||||||||

Radiotherapy |

28 |

15 |

0.048 |

32 |

11 |

0.003 |

21 |

18 |

4 |

0.003 |

Chemoradiotherapy |

126 |

135 |

129 |

132 |

71 |

113 |

77 |

|||

Discussion

In this study, we found that SAA level and EBV DNA copy number were independent predictors of OS in a cohort of NPC patients. Here, we combined SAA and EBV DNA, a parameter we called S-D grade, to assess its relationship with overall survival in NPC patients, and compared the predictive power of S-D grade with traditional TNM staging systems using C-index, ROCt curve, NRI, and IDI. Our results showed that the S-D grade was better able to predict overall survival with more accuracy than the TNM staging system, which might facilitate individualized prediction for future consultation.

SAA was synthesized mainly in the liver, and its expression regulated by cytokines including interleukins 1 (IL-1) and 6 (IL-6) released from activated macrophages [22]. Over-expression of SAA has previously been reported in NPC, renal cancer, gastric cancer, hepatocellular cancer, melanoma, breast cancer, and endometrial cancers [10, 23-29]. SAA can stimulate the expression of MMP-9 by macrophages, which in turn facilitates cancer cell metastasis [30]. Potentially, SAA could promote cancer progression by inhibiting platelet adhesion and enhancing plasminogen activation, both of which were involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation and tissue remodeling [31, 32]. Conversely, SAA may have a role in combating malignancies via the inhibition of cell adhesion to ECM glycoproteins [33]. SAA had also been reported to have a role in cancer prognosis in renal cell carcinoma [34, 35], lung [9, 36], breast cancer [12], esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [11] and hepatocellular carcinoma [13]. SAA level was tremendous increased at time of relapse in NPC patients, and showed potential as a useful biomarker to monitor relapse of NPC [23]. Previously, Chen et al. [37] reported that pretreatment SAA had a certain relationship with the prognosis of NPC, and patients with high levels of SAA had poor outcomes. In this study, they reported that SAA wasn't an independent prognostic factors and they did not assess the use of integrated SAA and EBV DNA (S-D grade) in the prognosis of NPC.

A strength of this study was the combination of SAA level and EBV DNA copy number (S-D grade) in predicting the prognosis of patients with NPC, and the use of both common approaches (C-index and ROCt curve) and novel metrics (NRI and IDI) to assess discrimination ability. Each approach all showed the S-D grade had better predictive accuracy than TNM staging systems.

Of course, our study had some limitations. First, we can't avoid potential selection biases due to the retrospective nature. Second, our data was obtained from one centre and and the lack of an independent validation cohort to assess the predictive power of S-D grade. Therefore, our results should be validated in other data sets in future study. Third, the C-index value for S-D grade of 0.689, which was not very high. We believed that the S-D grade could combine with other prognostic factors to improve the prediction of outcomes in NPC patients. In addition, more detailed study regarding the relationship between the S-D grade and the prognosis of NPC patients should be performed throughout the whole treatment period, including prior to treatment, during treatment, and following treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we reported a novel S-D grade system that can be used to predict prognosis in NPC patients. The S-D grade provided a more predictive accuracy and discriminative ability for the OS compared with the TNM staging system. In the future, it could be used to help clinicians with decision-making and guiding treatment of patients with NPC.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2018A030313622) and funded by the Open Project Program of the State Key Laboratory of Proteomics (SKLPO201703).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Director of Clinical Laboratories, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center for providing support on research conditions in this study.

Authors' contributions

SLC and YFC are senior authors who contributed in study design. JPL selected patients for the study and collected clinical data. SGP, HC and LZ performed data analysis, CCL wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data of this study are available from professor Shulin Chen, the State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China with the reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was considered and approved by Ethics Committees of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. All patients informed in the consent form for study participation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

-

- AUC

-

- the areas under ROC curve

-

- CRP

-

- C-reactive protein

-

- C-index

-

- concordance statistics

-

- EBV

-

- Epstein-Barr virus

-

- IDI

-

- integrated discrimination improvement

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- LMR

-

- lymphocyte/monocyte ratio

-

- NRI

-

- net reclassification index

-

- NPC

-

- nasopharyngeal carcinoma

-

- NLR

-

- neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio

-

- OS

-

- overall survival

-

- PLR

-

- platelet/lymphocyte ratio

-

- ROC

-

- receiver operating characteristic

-

- ROCt

-

- time-dependent ROC curve

-

- SAA

-

- serum amyloid A

-

- S-D grade

-

- integrated SAA and EBV DNA

-

- TNM

-

- tumor Node Metastasis stage

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.