European guidelines on achalasia: United European Gastroenterology and European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility recommendations

Abstract

Introduction

Achalasia is a primary motor disorder of the oesophagus characterised by absence of peristalsis and insufficient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation. With new advances and developments in achalasia management, there is an increasing demand for comprehensive evidence-based guidelines to assist clinicians in achalasia patient care.

Methods

Guidelines were established by a working group of representatives from United European Gastroenterology, European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility,European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology and the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery in accordance with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II instrument. A systematic review of the literature was performed, and the certainty of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation methodology. Recommendations were voted upon using a nominal group technique.

Results

These guidelines focus on the definition of achalasia, treatment aims, diagnostic tests, medical, endoscopic and surgical therapy, management of treatment failure, follow-up and oesophageal cancer risk.

Conclusion

These multidisciplinary guidelines provide a comprehensive evidence-based framework with recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of adult achalasia patients.

Abbreviations

-

- AGREE

-

- Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- BTX

-

- botulinum toxin

-

- EA

-

- oesophageal adenocarcinoma

-

- EAES

-

- European Association of Endoscopic Surgery

-

- ESGAR

-

- European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology

-

- ESNM

-

- European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility

-

- GORD

-

- gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

-

- GRADE

-

- Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation

-

- HRM

-

- high-resolution manometry

-

- IP

-

- impedance planimetry

-

- IRP

-

- integrated relaxation pressure

-

- LOS

-

- lower oesophageal sphincter

-

- LHM

-

- laparoscopic heller myotomy

-

- OGJ

-

- oesophago-gastric junction PD, pneumatic dilation

-

- PICO

-

- patient, intervention, control, outcome

-

- POEM

-

- peroral endoscopic myotomy

-

- PPI

-

- proton pump inhibitor

-

- RCT

-

- randomised controlled trial

-

- SSC

-

- squamous cell carcinoma

-

- TBE

-

- timed barium oesophagram

-

- UEG

-

- United European Gastroenterology.

Introduction

Achalasia is a primary motility disorder in which insufficient relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) and absent peristalsis result in stasis of ingested foods, subsequently leading to oesophageal symptoms of dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain or weight loss.1 Achalasia occurs as an effect of the destruction of enteric neurons controlling the LOS and oesophageal body musculature by an unknown cause, most likely inflammatory. Idiopathic achalasia is a rare disease and affects individuals of both sexes and all ages. The annual incidence is estimated between 1.07 and 2.2 cases per 100,000 individuals, with prevalence rates estimated between 10 and 15.7 per 100,000 individuals.2–4

A diagnosis of achalasia should be considered when patients present with dysphagia in combination with other oesophageal symptoms and when upper endoscopy has ruled out other disorders. Barium oesophagogram may reveal a classic ‘bird’s beak’ sign, oesophageal dilation or a corkscrew appearance. Oesophageal manometry is the golden standard for the diagnosis of achalasia. Incomplete relaxation of the LOS, reflected by an increased integrative relaxation pressure, in the absence of normal peristalsis, are the diagnostic hallmarks. The use of high-resolution manometry (HRM) has led to the subclassification of achalasia into three clinically relevant groups based on oesophageal contractility patterns, as seen in Table 1.

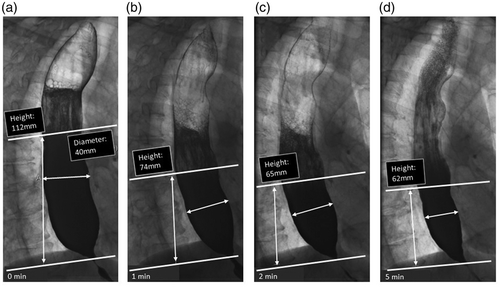

Interpretation of timed barium esophagram. Radiographs taken 0, 1, 2 and 5 minutes in left posterior oblique position after ingestion of 100 to 200 mL low-density barium suspension in an achalasia patient. Measurement of height and width of barium column, measured from the OGJ to the barium-foam interface. Barium height of >5 cm at 1 min and >2 cm at 5 min are suggestive of achalasia.

| Type I | Classic achalasia | • Median IRP > cut-offa • 100% failed peristalsis |

|

| Type II | Achalasia with oesophageal compression | • Median IRP > cut-offa • 100% failed peristalsis • ≥20% pan-oesophageal pressurisation |

|

| Type III | Spastic achalasia | • Median IRP > cut-offa • No normal peristalsis • ≥20% premature contraction with DCI >450 |

|

- a The cut-off for IRP is catheter-depending, varying between 15 and 28 mmHg.

- DCI: distal contractile integral; IRP: integrated relaxation pressure.

The clinical care of patients with achalasia has changed significantly in the past decade under the influence of new developments such as HRM, per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) and studies providing new insights regarding achalasia subtypes, cancer risk and follow-up. Given the substantial growth of knowledge in past years, there is need for comprehensive, evidence-based European guidelines covering all aspects of the disease. These multidisciplinary guidelines aim to provide an evidence-based framework with recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of adult achalasia patients. Chagas disease and achalasia secondary to other disorders, as can be seen after fundoplication, bariatric surgery, sarcoid infiltration, opiate usage or malignancy, are not covered by these guidelines. These guidelines are intended for clinicians involved in their management, including gastroenterologists, endoscopists, radiologists, gastrointestinal (GI) surgeons, dietitians and primary-care practitioners.

Methodology

The achalasia guidelines working group

Ten researchers and clinicians with recognised expertise in the field of clinical achalasia management were gathered (A.B., G.B., P.F., A.P., S.R., A.S., A.T., E.T., B.W. and G.Z.) on behalf of United European Gastroenterology (UEG), the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM), the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) and The European Association of Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) to form a guidelines expert working group. All concerned societies were contacted and asked to support the guidelines by appointing one or two representatives for the guidelines committee. First, the guidelines development team (R.O.N., A.B. and M.L.) drafted the guidelines protocol and the preliminary list of clinical topics to be covered by the guidelines. This list was circulated to a panel of achalasia patients. Based upon patients’ interests, the final list of research questions was formatted into the PICO (patient, intervention, control, outcome) framework, and presented to all members of the guidelines working group at an initial meeting, which occurred on 23 October at UEG Week 2018. All working group members were assigned to one of the subgroups (diagnosis, treatment or follow-up) and were responsible for the elaboration of one or multiple research questions. Results of the search strategies and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) assessments were first discussed in conference calls by each group and checked again for completeness, after which these documents were updated and subsequently sent to the entire group in advance of a face-to-face consensus meeting.

From assessment of evidence to recommendation

An electronic literature search was performed on 18 October 2018 using MEDLINE, EMBASE (accessed via Ovid), The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (The Cochrane Library) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) without restrictions of language or publication year. The search strategy and the process of study selection categorised per research question can be found in Appendix A. Risk of bias was assessed using the appropriate study-design specific tools (Appendix B). The certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADE methodology (www.gradeworkinggroup.org) and, for each outcome, graded into four levels: high, moderate, low or very low quality (Table 2). Based on the certainty of evidence and the balance between desirable and undesirable outcomes, patient values and preferences, applicability, feasibility, equity and costs/resources, recommendations were categorised into four final categories (strong or conditional recommendations in favour of or against an intervention), as proposed by GRADE (Table 3). In case of insufficient or limited evidence, research questions were answered by and classified as ‘expert opinion’. The results of data extraction, the risk of bias and quality of the evidence assessments are presented in Appendices C and D.

| Certainty of evidence | Definition |

|---|---|

| High | We are very confident that the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect. |

| Moderate | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. |

| Low | Our confidence in the estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of effect. |

| Very low | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. |

| Strength of recommendation | Wording in the guideline | For the patient | For the clinician |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | ‘We recommend…’ | Most individuals in this situation would want the recommended course and only a small proportion would not. | Most individuals should receive the recommended course of action. Formal decision aids are not likely to be needed to help individuals make decisions consistent with their values and preferences. |

| Conditional | ‘We suggest…’ | The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course, but many would not. | Different choices would be appropriate for different patients. Decision aids may be useful in helping individuals in making decisions consistent with their values and preferences. Clinicians should expect to spend more time with patients when working towards a decision. |

Consensus process

In order to establish consensus-based recommendations, a second physical meeting was organised in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, on 11 April 2019. GRADE assessments and recommendations were presented and discussed. Voting was conducted according to the nominal group technique and based upon a six-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = mostly disagree; 3 = somewhat disagree; 4 = somewhat agree; 5 = mostly agree; 6 = strongly agree). A recommendation was approved if >75% of the members agreed (reflected by a Likert score of 4–6).

Recommendations

Clinical questions formed the basis of the systematic literature reviews (Appendix A in the Supplemental Material). The working group formulated 30 recommendations based on these reviews (Table 4).

| Recommendations | Strength | Certainty of evidence | Voting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | ||||

| 1.1 | Achalasia is a disorder characterised by insufficient LOS relaxation and absent peristalsis. It is usually primary (idiopathic) but can be secondary to other conditions that affect oesophageal function. In idiopathic achalasia, the enteric neurons controlling the LOS and oesophageal body musculature are affected by an unknown cause, most likely inflammatory. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| 1.2 | We recommend using high-resolution manometry (with topographical pressure presentation) to diagnose achalasia in adult patients with suspected achalasia. | Strong | Moderate | 100% |

| 1.3 | We suggest using a barium oesophagram to diagnose achalasia if manometry is unavailable, although it is less sensitive than oesophageal manometry. The working group suggests using TBO, if available, over standard barium oesophagram. | Conditional | Moderate | 100% |

| 1.4 | We suggest against making the diagnosis of achalasia solely based on impaired OGJ distensibility as measured with impedance planimetry. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| 1.5 | (a) We suggest against making the diagnosis of achalasia solely based on endoscopy. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| (b) We suggest performing endoscopy in all patients with symptoms suggestive of achalasia to exclude other diseases. | Expert opinion | – | 77.8% | |

| 1.6 | We suggest additional testing using CT or endoscopic ultrasound only in those achalasia patients suspected of malignant pseudo-achalasia. Multiple recognised risk factors for malignant pseudo-achalasia, for example >55 years old, duration of symptoms <12 months, weight loss >10 kg, severe difficulty passing the LOS with a scope may prompt further imaging. | Conditional | Low | 100% |

| 1.7 | We suggest providing the patient with the following information on the disease and the treatment: Information on the disease : • normal function of oesophagus; • rare condition that affects the neurons, leads to LES dysrelaxation and absent peristalsis, exact cause not known; • no increased chance of disease in siblings; • what might happen if left untreated; • no progression to other organs; • small increased risk of cancer. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| Information on treatment options : • explanation of all treatment options, choice of treatment is based upon shared decision making; • treatment is not curative but does improve symptoms; • risk of complications; • risk of reflux; • efficacy of treatments. | ||||

| Treatment | ||||

| 2.1 | (a) We suggest that in the treatment of achalasia, symptom relief should be regarded as the primary aim. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| (b) We suggest that improvement of objectively measured oesophageal emptying on barium oesophagram should be regarded as an important additional treatment aim. | Expert opinion | – | 100% | |

| 2.2 | We suggest against the use of calcium blockers, phosphodiesterase inhibitors or nitrates for the treatment of achalasia. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| 2.3 | BTX therapy can be considered an effective and safe therapy for short-term symptom relief in oesophageal achalasia. | Conditional | Moderate | 88.9% |

| 2.4 | Graded pneumatic dilatation is an effective and relatively safe treatment for oesophageal achalasia. | Strong | High | 100% |

| 2.5 | POEM is an effective and relatively safe treatment for achalasia. | Strong | High | 100% |

| 2.6 | LHM combined with an anti-reflux procedure is an effective and relatively safe therapy for achalasia. | Strong | High | 100% |

| 2.7 | We suggest taking age and manometric subtype into account when selecting a therapeutic strategy. | Conditional | Moderate | 100% |

| 2.8 | (a) Treatment decisions in achalasia should be made based on patient-specific characteristics, patient preference, possible side effects and/or complications and a centre’s expertise. Overall, graded repetitive PD, LHM and POEM have comparable efficacy. | Strong | Moderate | 100% |

| (b) BTX should be reserved for patients who are unfit for more invasive treatments, or in whom a more definite treatment needs to be deferred. | Conditional | Moderate | 100% | |

| 2.9 | We suggest treating recurrent or persistent dysphagia after LHM with PD, POEM or redo surgery. | Conditional | Very low | 100% |

| 2.10 | We suggest treating recurrent or persistent dysphagia after POEM with either re-POEM, LHM or PD. | Conditional | Very low | 100% |

| 2.11 | Oesophagectomy should be considered the last resort to treat achalasia, after all other treatments have been considered. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| 2.12 | We suggest against oesophageal stents and intrasphincteric injection of sclerosing agents in the treatment of achalasia. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| Follow-up | ||||

| 3.1 | (a) Patients with recurrent or persistent dysphagia after initial treatment should undergo repeat evaluation with TOB with or without oesophageal manometry. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| (b) Repeat endoscopy should be considered in patients with recurrent dysphagia. | Expert opinion | – | 100% | |

| 3.2 | (a) In patients with persistent or recurrent chest pain, inappropriate emptying due to ineffective initial treatment or recurrent disease should be excluded by TBO with or without oesophageal manometry. For type III achalasia, we suggest a repeat HRM to exclude or confirm persistent spastic contractions. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| (b) If there is no evidence of impaired oesophageal emptying, empirical treatment with PPI, endoscopy and/or 24-hour pH-(impedance)metry can be considered. | Expert opinion | – | 100% | |

| 3.3 | (a) We suggest follow-up endoscopy to screen for GORD in patients treated with myotomy without anti-reflux procedure. | Expert opinion | – | 100% |

| (b). In case of reflux symptoms in the absence of reflux esophagitis, TBO, empiric PPI therapy and/or 24-hour oesophageal pH-(impedance) monitoring can be considered. | Expert opinion | – | 100% | |

| (c) PPI are the first-line treatment of GORD after achalasia treatment. We recommend lifelong PPI therapy in patients with oesophagitis > grade A (LA classification). | Expert opinion | – | 100% | |

| 3.4 | We suggest against performing systematic screening for dysplasia and carcinoma. However, the threshold of upper GI endoscopy should be low in patients with recurrent symptoms and long-standing achalasia. | Conditional | Low | 100% |

- LOS: lower oesophageal sphincter; TBO: timed barium oesophagram; OGJ: oesophago-gastric junction; CT: computed tomography; BTX: botulinum toxin; POEM: per-oral endoscopic myotomy; LHM: laparoscopic Heller myotomy; PD: pneumatic dilation: PPI: proton pump inhibitors; GORD: Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease; GI: gastrointestinal.

1. Achalasia diagnosis

1.1. What is the current definition of achalasia?

Recommendation 1.1

Achalasia is a disorder characterised by insufficient LOS relaxation and absent peristalsis. It is usually primary (idiopathic) but can be secondary to other conditions that affect oesophageal function. In idiopathic achalasia, the enteric neurons controlling the LOS and oesophageal body musculature are affected by an unknown cause, most likely inflammatory.

Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

1.2. What is the value of HRM and conventional manometry in achalasia diagnosis?

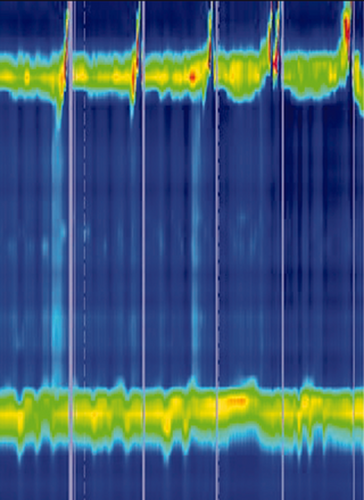

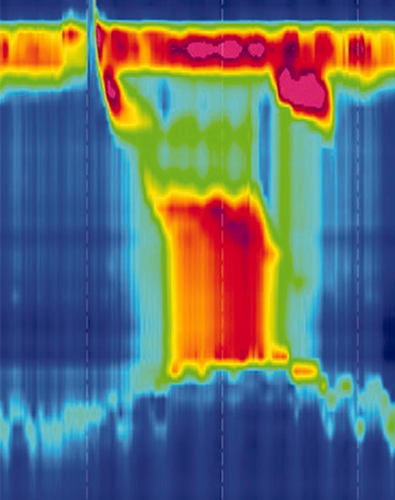

The diagnosis of achalasia requires not only impaired oesophago-gastric junction (OGJ) relaxation, but also absent or abnormal peristalsis. Therefore, oesophageal manometry is considered as being the gold standard for the diagnosis of achalasia, as it evaluates both pressures of the LOS and contractility of the oesophageal body. Worldwide, HRM, usually defined as manometry carried out with a catheter with at least 21 pressure sensors spaced at 1-cm intervals,5 is rapidly replacing conventional manometry. The generally perceived advantages of HRM over conventional manometry are that positioning of the catheter is less critical and that interpretation of the recorded pressures, displayed in the form of topographical colour-coded plots, is more intuitive.

In four of the five included studies, the diagnosis of achalasia was made with HRM more often than with conventional manometry.6–9 However, one may argue that a higher rate of achalasia diagnosis with HRM does not prove that HRM is better than conventional manometry; HRM might also lead to more false-positive findings. The only prospective randomised trial that compared HRM and conventional manometry9 had the additional advantage of defining the clinical outcome after six months as the gold standard, and found a superior sensitivity of HRM for the diagnosis of achalasia to that of conventional manometry (93% vs. 78%). The specificities of both tests were equal (100%).9

In two studies, the diagnostic values of imaging techniques were compared to manometry.10,11 The results of these two studies lend some support to the notion that manometry rather than imaging is the gold standard for the diagnosis of achalasia.

Recommendation 1.2

We recommend using HRM (with topographical pressure presentation) to diagnose achalasia in adult patients with suspected achalasia. Strong recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 66.7%; A+, 33.3%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

1.3. What is the value of (timed) barium swallow studies in achalasia diagnosis?

The barium oesophagram is generally seen as a valuable and complementary, but relatively insensitive, diagnostic test. One study evaluated the diagnostic value of barium oesophagraphy in comparison to HRM and found a high sensitivity but poor specificity for detecting dysmotility. The authors concluded that barium swallow studies accurately rule out achalasia-related dysmotility but are not very helpful in diagnosing other causes of dysmotility.12 Two studies comparing barium oesophagraphy with conventional manometry found sensitivities for achalasia diagnosis between 58% and 75%.11,13 However, as the positive predictive accuracy was 96%, the authors concluded that the barium oesophagram is a useful tool in achalasia diagnosis.11 Similar sensitivity and specificity rates were obtained in another study comparing barium swallow studies with HRM; the diagnostic sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of the barium oesophagram were 78.3%, 88.0% and 83.0%, respectively.14 Consequently, it may be concluded that diagnosing achalasia by using barium oesophagram alone has a limited yield. The technique of timed barium oesophagram (TBO) is similar to the usual barium swallow study but uses set time intervals (one, two and five minutes) after ingestion of a fixed barium suspension to measure the height and width of the barium column in order to assess oesophageal emptying more objectively (Figure 1).15 Because of this advantage, TBO is generally preferred over a standard barium oesophagram. One study compared TBO to HRM, and found a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 86%.15

Recommendation 1.3

We suggest using a barium oesophagram to diagnose achalasia if manometry is unavailable, although it is less sensitive than oesophageal manometry. The working group suggests using TBO, if available, over standard barium oesophagram. Conditional recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 88.9%; A+, 11.1%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

1.4. What is the value of oesophageal impedance planimetry in the diagnosis of achalasia?

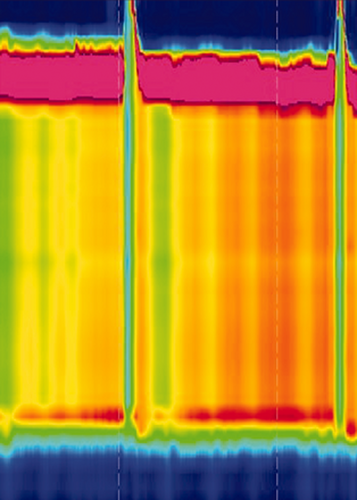

Oesophageal impedance planimetry is a technique in which the cross-sectional area of the oesophagus is simultaneously measured at multiple levels using a saline-filled cylindrical bag containing an array of impedance electrodes.6 The commercially available device for endoluminal impedance planimetry is known as Endoflip®.

Studies using impedance planimetry have consistently demonstrated that the distensibility of the OGJ is reduced in untreated achalasia compared to healthy controls.16–19 A systematic review identified six studies with data on OGJ distensibility in untreated achalasia patients (N = 154) and five studies with data in healthy subjects (N = 98), and found that at 40 mL distension, there was a clear difference between the two groups (point estimates <1.6 mm2 /mmHg and >2.7 mm2 /mmHg in patients and controls, respectively).20

However, in order to distinguish achalasia from OGJ outflow obstruction, information about the motility of the tubular oesophagus is required, which is not provided by impedance planimetry measurement. Recent studies indicate that dynamic impedance planimetry can also provide information on peristalsis.21,22 However, this technique assesses distension- rather than swallow-induced contractions, and requires sedation. Furthermore, high-quality diagnostic studies comparing impedance planimetry with the gold standard HRM are not available yet. In line with this, one recommendation from a recent American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update on functional lumen imaging is that clinicians should not make a diagnosis of achalasia based on impedance planimetry alone.23

There are data to suggest that impedance planimetry may be used as an additional tool to diagnose achalasia in patients who do not meet the manometric criteria (Chicago 3.0) for achalasia. In 13 patients with symptoms and signs of achalasia but with manometrically normal integrated relaxation pressure (IRP), OGJ distensibility was below the lower limit of normal. Treating these patients as if the diagnosis was achalasia resulted in a decrease in symptoms.24 This observation suggests that impedance planimetry may be a useful complementary diagnostic tool for the diagnosis of achalasia in a subset of patients with a low IRP.

Recommendation 1.4

We suggest against making the diagnosis of achalasia solely based on impaired OGJ distensibility as measured with impedance planimetry.

Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

1.5. What is the value of endoscopy in achalasia diagnosis?

Thorough endoscopic evaluation of the OGJ and gastric cardia is recommended in all patients with symptoms suggestive of achalasia in order to exclude other diseases, especially to rule out malignancies. However, the value of endoscopy in achalasia diagnosis is relatively low. Depending on the stage of disease, endoscopic evaluation can suggest a diagnosis of achalasia in 30–50% of patients. Achalasia diagnosis can easily be missed, as endoscopic abnormalities are uncommon in early-stage achalasia.25–27 In more advanced stages, a diagnosis of achalasia is supported by endoscopic findings such as an oesophageal dilatation with axis deviation and tortuosity and retained saliva and food in the oesophagus.28–30

Recommendation 1.5

(a) We suggest against making the diagnosis of achalasia solely based on endoscopy. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%] (b) We suggest performing endoscopy in all patients with symptoms suggestive of achalasia to exclude other diseases.

Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 77.8% agree [Vote: A++, 77.8%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 22.2%; D++, 0%]

1.6. In which patients should additional diagnostic tests be performed in order to exclude pseudo-achalasia?

Malignant pseudo-achalasia is a condition in which a patient is initially diagnosed with achalasia, and sometimes even treated for achalasia, but is later found to have an underlying malignancy as the primary cause. This can occur in a submucosally growing adenocarcinoma of the cardia, locally advanced pancreatic cancer, submucosal metastases or anti-Hu-producing carcinomas (typically small-cell lung carcinomas).31 Certainly not all patients diagnosed with achalasia should undergo additional testing in the form of a computed tomography (CT) scan or endoscopic ultrasound to rule out malignancy. However, valuable time is missed if malignancy is not detected at an early stage. Only two studies have addressed the issue of how to identify patients with malignant pseudo-achalasia.32,33 Both case-control studies identified the same differences between patients with primary achalasia and patients with malignant pseudo-achalasia: relatively short duration of symptoms, considerable weight loss and older age. The study by Ponds et al. also identified difficulty introducing the endoscope in the stomach, as mentioned by the endoscopist, as a risk factor. A model was produced in which the presence of fewer than two risk factors did not result in increased risk for malignancy, while risk increased with the presence of two or more risk factors. The authors recommend additional testing in these patients.

Recommendation 1.6

We suggest additional testing using CT or endoscopic ultrasound only in those achalasia patients suspected of malignant pseudo-achalasia. Multiple recognised risk factors for malignant pseudo-achalasia, for example >55 years of age, duration of symptoms <12 months, weight loss >10 kg, severe difficulty passing the LOS with a scope, may prompt further imaging. Conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 66.7%; A22.2%; A, 11.1%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

1.7. What information should the newly diagnosed patient receive?

We recommend providing the patient with information on the disease and the treatment given in Table 1.7.1.

| Information on the disease: |

| • normal function of the oesophagus; |

| • rare condition that affects the neurons, leads to LOS dysrelaxation and absent peristalsis, exact cause not known; |

| • no increased chance of disease in siblings; |

| • what might happen if left untreated; |

| • no progression to other organs; |

| • small increased risk of cancer. |

| Information on treatment options: |

| • explanation of all treatment options, choice of treatment is based upon shared-decision making; |

| • treatment is not curative but does improve symptoms; |

| • risk of complications; |

| • risk of reflux; |

| • efficacy of treatments. |

| Expert opinion recommendation |

| Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%] |

2. Achalasia treatment

2.1. What should we aim for when treating achalasia patients?

Treatment can be considered for reducing symptoms and consequently improving quality of life. As the evidence for the use of standardised questionnaires in the clinical setting is limited, a thorough clinical assessment of oesophageal symptoms before and after therapy should be used to evaluate treatment success. Second, treatment might prevent progression to end-stage disease and occurrence of late complications, such as aspiration and carcinogenesis. However, data on the natural history of disease to support this are scarce. There are series showing that if patients remain untreated, oesophageal distension progresses over a period of many years.34,35 There is some indirect evidence that treatment can prevent progression of the disease. In a study evaluating patients treated with pneumatic dilation (PD), the persistence of oesophageal stasis on TBO was associated with progressive oesophageal dilatation of 0.5 cm in a two-year period, whereas successful PD (no stasis on TBO) was not.36 Additionally, several surgical studies showed that treatment directed to LOS pressure is less effective in patients with late-stage disease and a decompensated oesophagus.37–39 In summary, there is some indirect evidence that adequate treatment might reduce the risk of progressive oesophageal dilation in patients with achalasia, potentially preventing a state of gross oesophageal dilation, which in turn is associated with a poor outcome. In addition to the amelioration of symptoms, improvement of objectively measured oesophageal emptying should therefore be regarded as an important additional treatment aim.

Recommendation 2.1

(a) We suggest that in the treatment of achalasia, symptom relief should be regarded as the primary treatment aim. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%] (b) We suggest that improvement of objectively measured oesophageal emptying on barium oesophagram should be regarded as an important additional treatment aim. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 66.7%; A22.2%; A, 11.1%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.2. What is the role of oral pharmacological therapy in achalasia?

There is no convincing evidence that treatment with smooth-muscle relaxants (calcium blockers, phosphodiesterase inhibitors or nitrates) provides symptomatic relief in adults with achalasia. The table presented in Appendix C summarises the available literature. None of the studies is of sufficiently high quality, has sufficient sample size or measured adequate end points to answer this question.40–46 Treatment with smooth-muscle relaxants can cause side effects and is therefore not recommended. It should certainly not delay an effective endoscopic or surgical treatment. Whether chest pain that is presumed to be due to spastic contractions can be relieved with medical therapy will be discussed in question 3.2.

Recommendation 2.2

We suggest against the use of calcium blockers, phosphodiesterase inhibitors or nitrates for the treatment of achalasia. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 66.7%; A+, 33.3%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.3. What is the comparative therapeutic efficacy and safety of endoscopic botulinum toxin injection in the treatment of achalasia?

Endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin (BTX) in the LOS has been compared to laparoscopic Heller myotomy (LHM) or endoscopic PD in several randomised controlled trials (RCTs).47–49 The results of these studies all point in the same direction: BTX injections result in a reduction in LOS pressure, stasis and symptoms in the short term, but generally the disease symptoms and signs recur with time. PD and BTX treatment are equally effective in the short term, while PD is the more effective endoscopic treatment in the long term (more than six months). LHM and BTX treatment are equally effective at the short term; LHM is the more effective treatment in the long term (more than six months).

Recommendation 2.3

BTX therapy can be considered an effective and safe therapy for short-term symptom relief in oesophageal achalasia. Conditional recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence Consensus: 88.9% agree [Vote: A++, 88.9%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D, 11.1%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.4. What is the comparative therapeutic efficacy and safety of endoscopic dilation?

PD has been compared to endoscopic BTX injections in the LOS, POEM and LHM. A factor of importance when comparing the different studies is the PD regimen followed, which varies widely. Broadly speaking, treatment regimens with multiple dilations performed in case of recurrent symptoms increase the efficacy. A single series of PDs is less efficacious than LHM or POEM, while there is no difference in safety between the two treatment groups.50–53 In studies in which repeated dilation was allowed upon symptom recurrence, the efficacy of PD generally approached that of LHM at a similar safety profile.54–58 Given the risk of perforation, it is always advisable to start with a 30-mm balloon in an untreated achalasia patient. A second dilation with a 35-mm balloon will prolong the time to recurrence.54,59

Recommendation 2.4

Graded PD is an effective and relatively safe treatment for oesophageal achalasia. Strong recommendation, high certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.5. What is the comparative therapeutic efficacy and safety of POEM?

POEM appears to be a safe treatment option with a low rate of serious adverse events.50,60 Although no long-term (beyond two years) follow-up data are available yet, POEM appears to be equally effective as LHM. In a recently published multi-centre RCT, treatment success rate (defined as a reduction in Eckardt score <3 and the absence of severe complications or need for retreatment) after two years of follow-up was significantly higher in patients treated with POEM compared to patients treated with PD.50 In this study, patients assigned to the PD arm were treated with a single 30-mm dilation, and received a second dilation with a 35-mm balloon if still symptomatic (which was the case in 50/66 (76%) patients). Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) occurs more frequently after POEM than after LMH or PD, but high grades of oesophagitis are uncommon.61,62 However, one should note that it is very challenging to objectify GORD in achalasia patients, as gastro-oesophageal acid reflux is hard to differentiate from fermentation due to stasis. Nevertheless, in patients with a high risk of post-procedure GORD who are unwilling to use proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, LHM or PD might be preferred over POEM.

Recommendation 2.5

POEM is an effective and relatively safe treatment for oesophageal achalasia. Strong recommendation, high certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.6. What is the comparative therapeutic efficacy and safety of surgical myotomy?

During a surgical cardiomyotomy, the spastic LOS is disrupted by cleaving the muscle layers of both the LOS and cardia, allowing the passage of food. Nowadays, the procedure is typically performed laparoscopically and combined with a partial anti-reflux procedure (fundoplication). A complete 360° wrap should be avoided in achalasia patients in order to prevent worsening, rather than relieving, the dysphagia.63 Six RCTs compared the efficacy of LHM versus PD (two of them reporting long-term results), and multiple meta-analyses were performed.51–58, 64, 65 These studies report a similar outcome for LHM and PD when multiple sessions of graded dilations were allowed (sequential dilations). However, LHM performed better than two sessions of PD. The meta-analysis (where PD outcome was assessed independently of the number of PD sessions) was in favour of LHM. LHM was more effective than PD in type III achalasia in a subgroup analysis of the European Achalasia Trial. One RCT compared LHM to BTX injection and showed a better outcome for LHM after six months of follow-up after an initial similar response.49 Only one RCT, comparing LHM and POEM, shows a similar symptomatic outcome for the two treatments after a follow-up of up to two years.60 A meta-analysis focusing on risk of iatrogenic reflux after POEM versus LHM suggested the increased risk of GORD after POEM.61

Recommendation 2.6

LHM combined with an anti-reflux procedure is an effective and relatively safe therapy for achalasia. Strong recommendation, high certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D, 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.7. What are predictors of treatment outcome? How to choose initial treatment

In order to guide therapeutic decisions, it is useful to distinguish patient types that are likely to respond favourably to a certain therapy. Patient-specific factors such as age, sex and manometric type are commonly believed to be predictive of treatment outcome, with the unfavourable effect of young age undoubtedly being the most frequently described example.66–69 A recently published review systematically assessed 75 studies that investigated potential patient-specific predictors.70 A total of 34 predictors were identified, but of all pre-therapeutic factors, only age and manometric subtype were identified as important predictors with a strong level of cumulative evidence. A meta-analysis confirmed that older patients (>45 years) responded better to PD treatment than younger individuals. Manometric subtype 3 was associated with poor treatment outcome in general. Interestingly, of the 49 included studies that evaluated sex as potential predictor, 90% did not find an association between sex and treatment outcome, indicating that sex most likely is not of predictive value in clinical decision making. The predictive value of some of the studied factors, such as chest pain and symptom severity, remains unclear, as the total body of evidence was inconclusive or insufficient to draw firm conclusions. It is suggested that age and manometric subtype should be taken into account when selecting a therapeutic strategy, in conjunction with information on efficacy and safety of the individual procedures, patient preference and local expertise.

Recommendation 2.7

We suggest taking age and manometric subtype into account when selecting a therapeutic strategy. Conditional recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D, 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.8. Overall recommendations on treatment (comparative effectiveness and safety)

Based on the systematic reviews and GRADE assessments of research questions 2.3–2.7 combined, the working group proposes the following overall recommendations with regard to achalasia therapy:

Recommendation 2.8

(a) Treatment decisions in achalasia should be made based on patient-specific characteristics, the patient’s preference, possible side effects and/or complications and a centre’s expertise. Overall, graded repetitive PD, LHM and POEM have comparable efficacy. Strong recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 55.6%; A+, 44.4%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%] (b) BTX therapy should be reserved for patients who are too unfit for more invasive treatments, or in whom a more definite treatment needs to be deferred. Conditional recommendation, moderate certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.9. How to treat recurrence post LHM

Minimally invasive surgical therapy in achalasia is effective in the majority of patients. However, symptom relapse occurs in 10–20% of patients in the long term.55 No adequate prospective controlled trials have been conducted on management of failed LHM due to low patient numbers. Current options for the treatment of LHM recurrence include endoscopic dilation, POEM or redo surgery. When no gross anatomic abnormalities are present, PD or POEM can be considered. Both procedures show equally modest efficacy rates, but PD is often regarded a less invasive first step.71–79 In the event of recurrence due to a too tight or twisted fundoplication, or a more complex anatomy with oesophageal distortion, fibrosis or a post-myotomy diverticulum, redo surgery may be considered. However, this is associated with a substantial risk of postoperative complications.74, 80–82

Recommendation 2.9

We suggest treating recurrent or persistent dysphagia after LHM with PD, POEM or redo surgery.Conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 22.2%; A+, 77.8%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.10. How to treat recurrence post POEM

Although POEM has good to excellent efficacy rates, treatment failure with recurrent or persistent symptoms does occur.50, 62, 83 In a recently published RCT comparing endoscopic myotomy with PD, the authors reported clinical failure in 8% of patients treated with POEM after two years of follow-up.50 Data on the best therapeutic approach after POEM failure are limited. Two case series reported success rates of 80–100% after three months of follow-up in patients treated with re-POEM after initial failure.84,85 Another study evaluating retreatment after POEM failure in 43 patients showed that retreatment with either LHM or re-POEM gives modest efficacy rates of 45% and 63%, respectively, whereas PD showed a poor efficacy of only 20%.86 These results may indicate the superiority of both POEM and LHM compared to PD in the management of POEM failure. However, it must be noted that the data to support this are weak and based on case series only. Moreover, PD is feasible and available in many centres, and is considered to be less invasive than re-myotomy and can therefore not be omitted completely in the management of this patient group.

Recommendation 2.10

We suggest treating recurrent or persistent dysphagia after POEM with either re-POEM, LHM or PD. Conditional recommendation, very low certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 77.8%; A+, 22.2%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.11. What are the indications for oesophagectomy?

Oesophagectomy for achalasia is associated with a high risk of complications and mortality.87,88 A systematic review of eight studies and 1307 patients who underwent oesophagectomy reported a complication rate of 19–50% and a mortality rate of 0–3.8%.87 In a large series of more than 500 patients, oesophagectomy was initially performed in <1% of the entire population, but ultimately 17% of patients required oesophageal resection, particularly those who failed surgical treatment or those with end-stage achalasia, which is often associated with massive oesophageal dilatation and tortuosity.82 In a report on 53 patients with end-stage achalasia who underwent oesophageal resection, the indications were tortuous mega-oesophagus (64%) or oesophageal stricture formation due to reflux (7%).89 Other indications for oesophageal resection are the presence of high-grade dysplasia or cancer. Although in-hospital mortality after oesophagectomy is lower in patients with achalasia than in patients with cancer (2.8% vs. 7.7%, respectively), it is still a substantial risk, especially as the indication for resection is not as strong as for malignant disease. Moreover, the overall postoperative complication rate is similar in both patient groups.90 Hence, oesophagectomy should be considered the last resort in end-stage achalasia, where disabling symptoms reoccur despite aggressive treatment.91,92 On the other hand, as the risk and complexity of oesophageal resection increases with the deterioration of a patient’s condition and nutritional status, end-stage achalasia should be carefully followed up to identify promptly when oesophagectomy is necessary.

Recommendation 2.11

Oesophagectomy should be considered the last resort to treat achalasia, after all other treatments have been considered. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 77.8%; A+, 22.2%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

2.12. What is the role of alternative therapies in the treatment of achalasia?

Several studies have investigated the use of alternative therapies such as oesophageal stents93–101 and intrasphincteric injection with ethanolamine oleate in achalasia treatment.102–105 Overall, there is no high-quality evidence to support that either of these therapies is effective for symptom relief in achalasia patients. Moreover, as occurrence of complications such as bleeding, stent migration or strictures are fairly common, use of these therapies is not recommended.

Recommendation 2.12

We suggest against oesophageal stents and intrasphincteric injection of sclerosing agents in the treatment of achalasia. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

3. Achalasia follow-up

3.1. How to diagnose and manage recurrent or persistent dysphagia after treatment

Despite treatment, a proportion of patients will experience ongoing or recurrent symptoms that significantly impair quality of life.86,106 In some cases, treatment does not lead to meaningful improvement in the first place (persistent symptoms). In others, a period of initial improvement is followed by subsequent recurrence. In general terms, the former suggests that initial treatment was incomplete, whereas the latter can be due to a variety of causes. There is no universal definition of what constitutes persistence or recurrence of symptoms. In most trials, an Eckardt score of >3 or a <50% improvement in symptoms is regarded as treatment failure.47, 50, 54, 107–109 However, this fails to distinguish between dysphagia and alternative troublesome symptoms such as regurgitation or chest pain. Although dysphagia is the most common ongoing symptom after achalasia treatment,86 the aetiology may be different from that in the treatment-naive setting (see Table 3.1.1).

| Common |

| • Persistent OGJ non-relaxation (e.g. incomplete myotomy) |

| • Post-treatment oesophageal fibrosis/scarring |

| • Excessively tight fundoplication post myotomy |

| • Gastro-oesophageal reflux (with or without oesophagitis) |

| • Aperistalsis and oesophageal stasis |

| • Functional dysphagia |

| Uncommon |

| • Development of malignant stricture |

| • Wrap migration after fundoplication and myotomy |

| • Benign stricture (e.g. from reflux) |

| • Extrinsic compression from hiatal hernia (para-oesophageal) or post-treatment collection |

Given the wide variety of potential causes of recurrent dysphagia, it is critical to undertake a comprehensive evaluation using objective testing in order to determine the pathophysiology underpinning the recurrent symptoms, and thus select the appropriate treatment. Conversely, in selected cases of persistent dysphagia, where the diagnosis of achalasia is beyond doubt, it may be appropriate to proceed immediately to further treatment without repeat testing (e.g. POEM after failure to improve with PD).

Since the commonest causes of recurrent dysphagia are incomplete myotomy, post-treatment scarring and oesophageal stasis due to aperistalsis and functional dysphagia, objective testing should be targeted at these conditions. TBO helps to determine if there is a persistent delay to oesophageal emptying, but reports regarding its usefulness as a predictor of long-term treatment success are conflicting.36, 55, 108 HRM provides additional information on LOS pressure. Impedance planimetry might be a useful complementary tool to assess OGJ distensibility and determine treatment efficacy.16,110 In patients with a suspicion of severe oesophagitis, possible candida oesophagitis or anatomic abnormalities endoscopy should be considered.

Recommendation 3.1

(a) Patients with recurrent or persistent dysphagia after initial treatment should undergo repeat evaluation with TBO with or without oesophageal manometry. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%] (b) Repeat endoscopy should be considered in patients with recurrent dysphagia. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 66.7%; A+, 33.3%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

3.2. How to diagnose and manage recurrent or persistent chest pain after treatment

Although chest pain is one of the main presenting symptoms of achalasia, its response to treatment is less well studied and remarkably underreported, most likely as dysphagia is considered the leading and most relevant symptom. Nevertheless, up to 64% of patients report chest pain, often occurring in the middle of the night (in 47% of patients with chest pain) and lasting from a few minutes to almost 24 hours.111 In contrast to dysphagia, chest pain is more challenging to treat and represents a risk factor for unsatisfactory treatment results for both PD and LHM.37, 54, 112 In approximately 19% of patients, chest pain is completely relieved following LHM, but in the remainder, chest pain persists, with an intensity that is less (73%), similar (21%) or even more severe (4%) than before surgery.113 Comparable results have been reported for PD.111 Of note, chest pain persists in these patients, even though dysphagia was successfully treated. In general, achalasia-associated chest pain seems to decrease with time, but complete disappearance is rather exceptional.111

The exact cause underlying (non-cardiac) chest pain remains unknown, and can be attributed to acid reflux, oesophageal motor abnormalities or visceral hypersensitivity. However, as chest pain is also considered to result from oesophageal distension as a result of incomplete emptying, treatment failure should first be excluded in patients with persistent or recurrent chest pain by performing oesophageal manometry and TBO.

If manometry (IRP above cut-off; catheter-depending, varying between 15 and 28 mmHg) 114 or TBO barium column height of >5cm after 5 minutes are abnormal,115 treatment should aim to normalise oesophageal emptying. HRM also serves to exclude spastic contractions as cause of the pain. If there is no evidence indicating insufficient treatment, one can consider investigation for GORD as the trigger of chest pain using 24-hour pH (impedance) monitoring and treat accordingly.116 Data demonstrating the effect of PPI on chest pain in achalasia are, however, lacking, and anecdotally the response to PPI is poor if there is chest pain without heartburn.

The management of achalasia patients with chest pain with no evidence of GORD and normal oesophageal emptying/IRP remains a major challenge, mainly as there are no or only a limited number of RCTs available. Hence, clinical decision making is mostly based on studies performed in patients with non-cardiac chest pain due to oesophageal dysmotility. Potential options for medical treatment are smooth-muscle relaxants (nifedipine, nitrates, diltiazem), BTX injection or neuromodulators (imipramine, venlafaxine, sertraline).116 However, the success rates are rather limited and/or the effect is short lasting (in the case of BTX). Of interest, evidence is accumulating that POEM might be effective in relieving chest pain in patients with achalasia and other primary oesophageal motility disorders. Several case series evaluating patients with hypercontractile oesophageal motility disorders and chest pain who were treated with POEM showed promising results.117–120 However, as none of the studies were sham-controlled, patient numbers were small and lengths of follow-up relatively short, future controlled data with longer follow-up are needed to investigate the exact role of POEM for patients with chest pain after initial achalasia treatment.

Recommendation 3.2

(a) In patients with persistent or recurrent chest pain, inappropriate emptying due to ineffective initial treatment or recurrent disease should be excluded by TBO with or without oesophageal manometry. For type III achalasia, we suggest a repeat HRM to exclude or confirm persistent spastic contractions. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 88.9%; A+, 11.1%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%] (b) If there is no evidence of impaired oesophageal emptying, empirical treatment with PPI, endoscopy and/or 24-hour pH (impedance) monitoring can be considered. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 100%; A+, 0%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

3.3. How to manage reflux disease after treatment

As the aim of achalasia treatment is to alleviate the OGJ obstruction, an expected side effect of treatment is the occurrence of GORD, usually defined in achalasia as the presence of reflux oesophagitis or pathological acid exposure. Indeed, GORD is frequently observed after treatment (10–31% of cases after PD,51–53, 55, 58, 121 5–35% after LHM52, 53, 55, 121–123 and up to 60% of patients after POEM50, 60, 61, 124–126). GORD complications, including peptic stricture, Barrett’s mucosa and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OA), have been reported after achalasia treatment.124, 126–130 Comparative studies demonstrated that the rate of GORD was similar after PD and LHM with fundoplication.121 One study showed that LHM without lateral and posterior dissection might also achieve sufficient reflux control.131 However, in other studies, the prevalence of GORD was significantly higher after POEM or LHM without fundoplication than after PD or LHM with fundoplication.50, 60, 62, 132 Therefore, systematic screening for GORD after achalasia treatment should be recommended if the risk for GORD is high. Moreover, due to the different GORD rates, the choice of achalasia treatment should take into account the risk of iatrogenic reflux disease. In line with this, empiric PPI therapy might be considered in patients who undergoing myotomy without an anti-reflux procedure.

GORD symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation are not reliable to diagnose GORD in achalasia patients, especially as regurgitation is also a hallmark of achalasia and poor oesophageal emptying. An upper endoscopy can reveal oesophagitis and Barrett’s mucosa as proof of GORD. Another way to diagnose GORD is 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring. The interpretation of this examination requires a careful review of pH tracings to eliminate periods of oesophageal fermentation.53 The correlation between oesophageal symptoms and objective diagnosis of GORD (including oesophagitis and oesophageal acid exposure) is poor.62, 123, 133–135 Upper GI endoscopy, TBO and 24-hour pH monitoring might be complementary.

So far, no study has clearly evaluated the management of GORD after achalasia treatment. Post-treatment GORD is usually treated successfully with PPI. The percentage of patients on PPI after achalasia treatment is up to 60%.60, 61, 136–138 Few other GORD treatments have been proposed for refractory cases and presented only as case reports (redo fundoplication, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, oesophagectomy, transoral incisionless fundoplication).89, 139, 140

Recommendation 3.3

a. We suggest follow-up endoscopy to screen for GORD in patients treated with myotomy without anti-reflux procedure. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 44.4%; A+, 44.4%; A, 11.1%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%] b. In case of reflux symptoms in the absence of reflux oesophagitis, TBO, empiric PPI therapy and/or 24-hour oesophageal pH-(impedance) monitoring can be considered. Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 77.8%; A+, 22.2%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%] c. PPI are the first-line treatment of GORD after achalasia treatment. We recommend lifelong PPI therapy in patients with oesophagitis >grade A (LA classification). Expert opinion recommendation Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 33.3%; A+, 55.6%; A, 11.1%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

3.4. Is surveillance endoscopy for dysplasia needed?

What is the incidence of oesophageal cancer in achalasia patients?

Achalasia is a risk factor for oesophageal cancer. Poor oesophageal clearance increases bacterial growth, chemical irritation and mucosal inflammation that can facilitate dysplastic changes of oesophageal epithelial cells and result in squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC).141 Furthermore, acid exposure secondary to reduction of OGJ pressure as a consequence of achalasia treatment may lead to Barrett’s mucosa and OA.142

The exact level of risk for oesophageal cancer (SCC and OA) is controversial. Differences in study design (retrospective or prospective, length of Follow-up, number of patients, countries) might explain some of the observed differences. While the absolute risk of oesophageal cancer is quite low in achalasia, the relative risk of cancer is higher in achalasia patients than in the general population (risk ratio to develop OA and SCC in achalasia patients is 6.63 and 72.65, respectively).143,144 Most of the cases of carcinoma are observed more than 10 years after symptom onset.144,145 The type of treatment does not influence the risk of cancer,130,146 but to date there are no long-term data following POEM. Cancer risk might be higher in males and in patients with Chagas disease.130, 146, 147

Screening practices differ among geographic regions (routine endoscopy vs. no endoscopy, screening intervals).92,148 Chromoendoscopy with lugol was proposed to improve the detection rate of dysplastic lesion, but the yield was low and hampered by stratification risk.145

Finally, the cost efficacy of the screening has not been demonstrated; the low absolute risk of cancer and the difficulty of identifying pre-neoplastic lesions might explain the absence of the advantage of screening achalasia patients for oesophageal cancer.

Recommendation 3.4

We suggest against performing systematic screening for dysplasia and carcinoma. However, the threshold of upper GI endoscopy should be low in patients with recurrent symptoms and longstanding achalasia. Conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence Consensus: 100% agree [Vote: A++, 66.7%; A+, 33.3%; A, 0%; D 0%; D+, 0%; D++, 0%]

Conclusions and future perspectives

The ESNM/UEG guidelines on the management of achalasia are the result of an evidence-based approach and international and multidisciplinary efforts. These guidelines provide recommendations for key aspects of the diagnosis and management of achalasia, combined with comments based on the best available literature and the opinions of leading European achalasia experts. The main objectives of these guidelines are to reduce variation in practice and to improve patient outcomes across Europe. Consequently, thorough and extensive dissemination of these guidelines is needed to assure high compliance in clinical practice. Promotion of these guidelines as well as education play a key role in this regard. Future well-designed clinical trials should address the knowledge gaps and unmet needs that have arisen during the development of these guidelines.

Declaration of conflicting interests

Research support: Bayer (A.B.), Crospon (S.R.), Diversatek (S.R.), Laborie (A.B.), Medtronic (S.R.), Nutricia (A.B.), Norgine (A.B.). Advisory, honoraria or consultation: Calypso (A.B.), Celgene (A.B.), Cook (P.F.), Diversatek (A.B.), EsoCap (A.B.), Ethicon (P.F.), Falk (A.B.), Fujifilm (P.F.), Laborie (A.B.), Medtronic (P.F., S.R.), Olympus (P.F.), Regeneron (A.B.). Speaker’s bureau: Actavis (A.P.), Falk (A.B.), Janssen-Cilag (A.P.), Laborie (A.B.), Mayoly Spindler (S.R.), Medtronic (A.B.), Takeda (A.P.). No disclosures or conflicts of interest: G.B., M.L., R.O.N., A.T., E.T., A.S., B.W., G.Z.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: These guidelines have been developed and funded within the United European Gastroenterology.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.