Predictors and characteristics of angioectasias in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding identified by video capsule endoscopy

Abstract

Background

In obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, angioectasias are common findings in video capsule endoscopy (VCE).

Objective

The objective of this study was to identify predictors and characteristics of small bowel angioectasias.

Methods

Video capsule examinations between 1 July 2001 and 31 July 2011 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding were identified, and those with small bowel angioectasia were compared with patients without a definite bleeding source. Univariate and multivariable statistical analyses for possible predictors of small bowel angioectasia were performed.

Results

From a total of 717 video capsule examinations, 512 patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding were identified. Positive findings were reported in 350 patients (68.4%) and angioectasias were documented in 153 of these patients (43.7%). These angioectasias were mostly located in the proximal small intestine (n = 86, 56.6%). Patients’ age >65 years (odds ratio (OR) 2.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.36–3.38, p = .001) and overt bleeding type (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.22–2.94, p = .004) were identified as significant independent predictors of small bowel angioectasia.

Conclusion

Angioectasias are the most common finding in VCE in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. They are mostly located in the proximal small bowel and are associated with higher age and an overt bleeding type.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) angioectasias represent dilated, ectatic, thin-walled vessels in the mucosa or submucosa and are the most common vascular anomalies in the GI tract. The pathogenesis and aetiology of angioectasias are unclear. Chronic hypoperfusion with consecutive relaxation of intestinal vascular smooth muscle due to sympathetic nerve stimulation1 and the overexpression of angiogenic factors2 have been proposed as possible factors in their development. The precise prevalence of angioectasias in the total population is unknown, and most patients with angioectasias are likely to remain asymptomatic without any bleeding episodes.3

Angioectasias are most frequently located in the colon and less frequently found in the upper GI tract or in the small bowel.4 Small bowel angioectasias have been most commonly described in the proximal small bowel,5-7 and the majority of patients are known to have more than one angioectasia in one or more parts of the GI tract.4 Elderly patients and patients with aortic stenosis, von Willebrand disease and chronic renal failure are more likely to have angioectasias.4

In obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, small bowel angioectasias have been reported as the source of bleeding in up to 80% of patients.8-10 Considering the frequency and the typically intermittent bleeding nature of angioectasias,10 possible predictors and distinct characteristics of these vascular lesions are of high clinical relevance, and thus were addressed in this retrospective study.

Patients and methods

This retrospective study included all patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding who underwent video capsule endoscopy (VCE) between 1 July 2001 and 31 July 2011 at a single tertiary referral hospital (Klinikum rechts der Isar der Technischen Universität München, Munich, Germany). These patients presented with overt bleeding (haematochezia, melaena, haematemesis) or occult bleeding (positive faecal occult blood test, iron deficiency anaemia, or an acute drop in haemoglobin). In all patients, prior esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy did not identify a bleeding source. In patients who received multiple VCEs, only the first complete examination was included in the analysis.

Video capsule endoscopy

VCE examinations were all done with the PillCam SB of the first and second generation (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland). Preparation for VCE included a fasting period of at least 12 hours. Intestinal lavage was conducted prior to the examination with a polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution. Patients were advised to drink 1 L of the solution the evening before and 1 L 2 hours prior to the examination. In addition, approximately 30 minutes prior to VCE, patients received 5 mL of simethicone solution (equals 350 mg simethicone, Pfizer Pharma GmbH, Berlin, Germany) to eliminate air bubbles and to improve visualization of the small bowel mucosa.11 Prokinetic drugs were not routinely administered during the VCE examinations. After administration of the video capsule, the patients were routinely asked to fast for another 4 hours. After this time, patients were allowed to drink clear liquids. After 8 hours, light meals were permitted. After completion of the VCE examination, images were transferred and analysed using the manufacturer’s standard software (Rapid Reader, Medtronic). Each capsule study was read at a standard speed of 12 frames per second and the findings were documented.

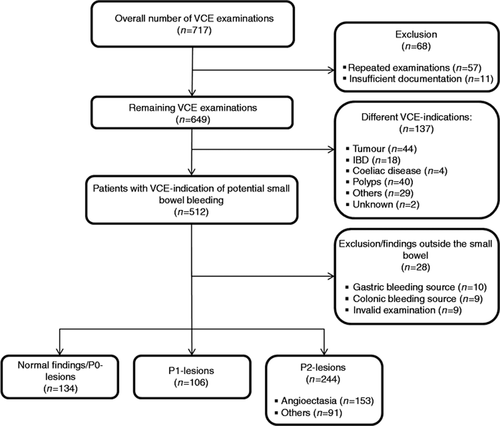

All VCE studies were evaluated for completeness (defined as passage of the video capsule into the caecum) and overall small bowel transit times. VCE findings were classified and labelled according to the Capsule Endoscopy Structured Terminology (CEST).12 VCE findings were furthermore graded on the P0–P2 grading system:13 P0, normal examination; P1, lesion with uncertain bleeding potential/insignificant finding; P2, lesion with significant finding. For further analysis, patients from groups P0 and P1 were combined as the group without a definite bleeding lesion. Patients from group P2 were divided into patients with angioectasia and patients with other significant lesions (Figure 1 ). The localization of angioectasias was defined by dividing the small bowel transit time into three equal parts. Angioectasias in the first part (defined as the first 1/3 of small bowel transit time) were defined as ‘proximal’, those in the second part (defined as 1/3–2/3 of the small bowel transit time) as ‘mid’, and angioectasias in the last part (defined as >2/3 of the small bowel transit time) were specified as ‘distal’ angioectasias. Occurrence of angioectasias was classified as single or multiple.

Example for a non-bleeding small bowel angioectasia in video capsule endoscopy.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). For quantitative data, mean and standard deviation (SD) are presented. Qualitative data are summarized by absolute and relative frequencies.

For the identification of predictive factors for the presence of small bowel angioectasia in VCE, univariate binary logistic regression analysis was used. The reference group for these analyses was the group of patients without definite bleeding lesions in VCE. Multivariable logistic regression models were subsequently fitted to the data, including all variables that were significantly associated with the presence of small bowel angioectasia in univariate analyses. The results of univariate and multivariable analyses are described by odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical tests were performed on a two-sided level of significance of α = 5%.

Results

Between 1 July 2001 and 31 July 2011, a total of 717 VCE examinations were identified. After exclusion of repeated examinations (n = 57), examinations without sufficient documentation (n = 11) and examinations that had been performed for a different indication (n = 137), 512 patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding were identified (Figure 2 ). The characteristics of these patients are listed in Table 1. Three hundred patients presented with overt bleeding (58.6%): 152 of these patients had melaena (50.7%), 130 patients had haematochezia (43.3%), 15 had both melaena and haematochezia (5%), and 3 patients had haematemesis (1%). Two hundred and twelve patients presented with occult bleeding (41.4%). The mean lowest haemoglobin level was 9.7 ± 2.3 g/dL. The use of antiplatelet drugs was reported in 245 patients (47.9%). One hundred and ten patients had anticoagulation therapy (23.6%), and 21 patients reported the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (4.5%). The most common co-morbidities were coronary heart disease in 163 patients (33.1%), chronic kidney disease (CKD) in 103 (20.9%) and aortic stenosis in 77 patients (15.7%); 26 patients had liver cirrhosis (5.3%).

Overview of VCE-examinations. IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; VCE: video capsule endoscopy.

| Number of patients (%)/(mean (±SD)) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years | 64.9 (15.5) |

| Male gender | 291 (56.8) |

| Lowest Hb value (g/dL) | 9.7 (2.3) |

| Platelet count (G/L) | 265.8 (114.8) |

| Patients with overt bleeding | 300 (58.6) |

| Melaena | 152 (50.7) |

| Haematochezia | 130 (43.3) |

| Melaena and haematochezia | 15 (5.0) |

| Haematemesis | 3 (1.0) |

| Patients with occult bleeding | 212 (41.4) |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | 96 (45.3) |

| Unclear decrease of Hb value | 67 (31.6) |

| Positive haemoccult test | 49 (23.1) |

| Co-morbidities | |

| Coronary heart disease | 163 (33.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 103 (20.9) |

| Aortic stenosis | 77 (15.7) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 26 (5.3) |

| Medication | |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 143 (30.6) |

| Clopidogrel | 61 (13.1) |

| Dual platelet inhibition | 41 (8.8) |

| Anticoagulant therapy | 110 (23.6) |

| Phenprocoumon | 83 (17.8) |

| Heparin | 27 (5.8) |

| NSAIDs | 21 (4.5) |

| Patients with preVCE blood transfusion | 177 (37.9) |

| 1–2 PRBCs | 114 (24.2) |

| 3–9 PRBCs | 53 (11.3) |

| ≥10 PRBCs | 10 (2.1) |

- Italics show mean (±SD) values. Hb: haemoglobin; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PRBCs: packed red blood cells; SD: standard deviation; VCE: video capsule endoscopy.

VCE examinations reported positive small bowel findings (P1 and P2 lesions) in 350 patients (68.4%) and negative results (P0 lesions) in 134 patients (26.2%). In 10 (2%) and 9 (1.8%) patients, the potential bleeding sources were identified in the stomach and the colon, respectively. In nine patients (1.8%), VCE examination was invalid, either due to failed passage of the capsule into the small bowel (five patients) or due to technical problems such as downloading or transmitting failures (four patients). Due to premature VCE battery depletion, small bowel transit was incomplete in 76 patients (14.8%). In four patients (0.8%), retention of VCE was reported, and VCE had to be retrieved endoscopically (three patients) or via surgery (one patient). Figure 2 summarizes the VCE findings in the 512 patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding.

In 350 patients with positive small bowel findings, angioectasias were reported as the definite bleeding source in 153 patients (43.7%). Occurrence of angioectasias was solitary in 66 (43.1%) and multiple in 87 patients (56.9%). Angioectasias were predominantly described in the proximal small intestine (n = 86, 56.6%) and less frequently in the middle (n = 39, 25.7%) or distal parts (n = 27, 17.8%) (p = .002). Multiple angioectasias were most frequently located in the proximal small intestine (proximal: 68.6%, middle: 35.9%, distal: 48.1%). Solitary angioectasias were predominantly described in the middle part of the small bowel (proximal: 31.4%, middle: 64.1%, distal: 51.9%).

Univariate analysis identified age >65 years, an overt bleeding type and CKD as predictors for angioectasias (Table 2 ). In multivariable analyses, age >65 years (OR 2.15, 95% CI 1.36–3.38, p = .001) and overt bleeding type (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.22–2.94, p = .004) were independent predictors for angioectasias. CKD, however, was not significantly associated with angioectasias (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.77–2.15, p = .341).

| OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (≤ 65 years a ; >65 years) | 2.21 | 1.44–3.40 | <. 001 |

| Gender (female ; male) | 0.94 | 0.63–1.41 | .766 |

| Hb-value (≥8 g/dL ; <8 g/dL) | 1.18 | 0.70–1.97 | .537 |

| Platelet count (≥150 G/L ; <150 G/L) | 1.37 | 0.72–2.59 | .338 |

| Bleeding type (occult ; overt) | 1.74 | 1.14–2.64 | .010 |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Coronary heart disease | 1.29 | 0.83–2.00 | .257 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.71 | 1.05–2.78 | .031 |

| Aortic stenosis | 1.12 | 0.64–1.97 | .684 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 1.75 | 0.73–4.24 | .212 |

| Medication | |||

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 0.96 | 0.61–1.52 | .862 |

| Clopidogrel | 1.54 | 0.85–2.79 | .156 |

| Dual platelet inhibition | 1.14 | 0.56–2.31 | .711 |

| Anticoagulant therapy | 0.95 | 0.58–1.57 | .851 |

| NSAIDs | 1.33 | 0.47–3.74 | .595 |

| preVCE blood transfusion | 1.21 | 0.79–1.87 | .384 |

- a Italics show the corresponding reference value. For comorbidities and medication use, the absence of the specific comorbidity/medication was considered as reference.

- CI: confidence interval; Hb: haemoglobin; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OR: odds ratio; VCE: video capsule endoscopy.

Discussion

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding is considered the most frequent indication for further endoscopic visualization of the small intestine via VCE.8 In our large retrospective study, about 80% of examinations were performed for this indication. The most frequent findings in our patients were small bowel angioectasias, in around 30%, which underlines the importance of these vascular lesions in obscure gastrointestinal haemorrhage. The majority of angioectasias in our data were documented with a multifocal occurrence (57%) preferably in the proximal small bowel (57%). Solitary angioectasias were predominantly found in the middle part. In only 18% of cases, angioectasias were located in the distal small intestine, where solitary and multifocal occurrences were distributed almost equally. Prior studies reported small bowel angioectasia rates between 15% and 50%,6, 9, 14-18 depending on the study design and differences in the patient collectives. In accordance with our data, angioectasias were mainly described in the proximal small bowel (jejunum and duodenum)5, 19-21 with a spatial clustering in these segments.21 Though the reason for this distribution remains unclear, it is advantageous for the endoscopist, as most angioectasias should be reachable by antegrade balloon enteroscopy or, even simpler, by push enteroscopy. However, it is important to keep in mind that the mucosa should always be screened for more than one angioectasia.

Although numerous studies have already evaluated the frequencies, characteristics and prognostic factors of small bowel lesions in general, data about prognostic factors for small bowel angioectasias are insufficient.5, 14, 19, 22-24 In comparison with our study, many of these retrospective studies had smaller sample sizes.5, 14, 22, 23 Other studies focused on risk factors for angioectasia rebleeding.18, 19 In our data, comprising 153 patients with small bowel angioectasias, multivariable logistic regression analysis identified older age (>65 years) as the most powerful independent predictive factor for small bowel angioectasia. This finding is in accordance with prior studies describing an increased diagnostic yield of VCE16, 25, 26 as well as a higher prevalence of angioectasias in the elderly.9, 14-17, 19, 27, 28 The reason for this higher rate of angioectasias remains unclear. However, an increased prevalence of concomitant diseases, medication intake and chronic mucosal hypoperfusion could be suspected. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of our data also identified overt bleeding as an independent predictive factor for small bowel angioectasias. In general, a higher diagnostic yield in VCE has been reported for an overt bleeding type.7, 9, 29, 30 This is most probably the reason for the overall higher percentage of positive findings in our study, comprising a higher proportion of patients with an overt bleeding type compared with prior studies.8, 9 For small bowel vascular lesions, conflicting results have been reported by different authors. However, compared with our data, these studies were mainly limited by restricted sample sizes.6, 14, 18, 22, 23 An explanation for the higher rate of angioectasias in patients with an overt bleeding type may be found in the more rapidly initiated VCE examination. VCE shows the highest diagnostic yield (up to 92%) when performed as closely as possible to a bleeding episode.7, 31 Interestingly, Kaufman et al.19 identified older age and active angioectasia bleeding as risk factors for angioectasia rebleeding. In addition, in 39 patients, Fan et al.24 described a higher risk for recurrent small bowel angioectasia bleeding in patients presenting with melaena and in patients >65 years. Thus, these patients should be closely monitored after the first angioectasia bleeding.

In our data, CKD was identified as an additional significant risk factor for angioectasias in univariate analysis. However, in multivariable logistic regression analysis, CKD did not prove to be an independent risk factor. This finding is in contrast to some prior studies describing advanced CKD as a risk factor for small bowel angioectasia in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding.23, 32, 33 In patients with an overt bleeding type, Sakai et al. identified CKD ≥stage 4 as a risk factor for angioectasias, independently of age and sex. However, in patients with an occult bleeding type, CKD was not a risk factor in these data.18 Our data, as well as the latter study, suggest that CKD is not an independent risk factor for small bowel angioectasias. The incidence of angioectasias in CKD may be overestimated due to an increased diffuse bleeding diathesis caused by platelet dysfunctions and increased platelet activation as well as anticoagulative treatment during hemodialysis.34 In our data, liver cirrhosis (OR 1.75, p = .212), coronary heart disease (OR 1.29, p = .257) and aortic valve stenosis (OR 1.12, p = .684) showed a non-significantly increased risk for small bowel angioectasias. So far, Yamada et al.22 have reported a higher prevalence of liver cirrhosis in a study comparing 18 patients with angioectasias with 181 patients without angioectasias (60% vs. 22%). Igawa et al.14 described liver cirrhosis to be a significant predictor of small bowel angioectasias in 64 patients with these vascular lesions, compared with 97 patients without. The total rate of patients with liver cirrhosis in this study was 13%. The authors of this study proposed portal hypertension and stasis of the blood-flow as the reason for an increased rate of angioectasias. In both studies, results seem to be limited with regard to sample size; however, our results may also be explained by the relatively low number of patients with liver cirrhosis (n = 26, 5.3%). A significantly higher risk for small bowel angioectasia in patients with coronary heart disease has been described in previous studies14, 23 and could be explained by chronic hypoperfusion of the mucosa and an increased expression of angiogenetic growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).6 The existence of an association between aortic stenosis and gastrointestinal bleeding (presumably due to angioectasias = Heyde’s syndrome) has been shown by a large epidemiological study.35 However, this study also showed that the percentage of patients with both conditions is low, which is also confirmed by our data.

Further analyses of possible predictors for small bowel angioectasias in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding included gender, haemoglobin value and number of blood transfusions (as possible indicators of the bleeding intensity), platelet count, NSAID therapy and antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. None of these parameters could be identified as further significant risk factors in the presented data. Lepileur et al. reported male sex to be a predictive factor of positive diagnosis by VCE in a large collective of 911 patients,9 and Esaki et al. noted a marked decrease of the haemoglobin value as a predictor for positive VCE findings.29 However, neither of these studies specifically addressed angioectasias. NSAIDs have been reported to increase the rates of small bowel erosions and ulcers15, 29 and have not been associated with angioectasias. Similarly to our data, Holleran et al.23 as well as Sakai et al.18 did not find a significant increase of angioectasia in patients with antiplatelet therapy (aspirin or clopidogrel). However, an increased risk was described for warfarin and a combination of aspirin and dipyridamole,23 both medications that were not used by our patients. When discussing the role of medications and positive small bowel findings in VCE, we believe that a selection bias needs to be considered. For example, in patients with anaemia and the use of NSAIDs, this therapy may often be discontinued, and VCE may only be performed when the anaemia or signs of bleeding persist.

The main limitation of the presented study is the retrospective monocentric design. During the study period of 10 years, different endoscopists interpreted the VCE examinations. However, analysis of VCE examinations was standardized and monitored by an experienced endoscopist. Localization of angioectasias was defined according to small bowel transit time in proximal, mid and distal, which is a common approach in other studies as well.19-21 This system does not exactly reflect the anatomical conditions of the small bowel; however, the morphologic characteristics of the small bowel do not always allow an exact identification of the different small bowel segments. Moreover, the PillCam SB of the first and second generation with a frame rate of 2 frames/s were used in our study – a higher diagnostic yield can be expected from the newest VCE generation, the PillCam SB-3, with a frame rate of 6 frames/s. Additionally, it is necessary to address how far angioectasias, and especially solitary angioectasias, are really the definite source of bleeding, particularly when there is no sign of active bleeding at the time of VCE. Indeed, the finding of a solitary angioectasia does not entail a 100% certainty that this angioectasia is the definite bleeding source, because angioectasias are also described in patients without a history of gastrointestinal bleeding. However, in the case of the positive finding of an angioectasia in the absence of any other bleeding sources, this angioectasia can be regarded as the most probable source in the setting of obscure gastrointestinal hemorrhage.4

In conclusion, angioectasias are mainly located in the upper third of the small bowel and preferentially show a multiple occurrence. Patients’ age >65 years and an overt bleeding type can predict the presence of angioectasias in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Thus, these patients might possibly benefit from early endoscopic small bowel intervention with the possibility of argon plasma coagulation (APC) by push enteroscopy or antegrade balloon enteroscopy without prior VCE. However, in all other cases, VCE can be recommended as the first-choice procedure, combining a high diagnostic yield with minimal invasiveness.

Conflict of interest

Christoph Schlag and Bruno Neu received speaker’s honoraria from Medtronic (Dublin, Ireland). All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the local ethical review board (Ethikkomission der Fakultät für Medizin der Technischen Universität München, 09/08/2011, No. 5100/11).

Informed consent

Since this was a retrospective study, no informed consent was obtained from the patients included.