The Hidden Side of Self-Criticism: A Cross-Sectional Cluster Analysis of Self-Compassion, Self-Focus, and Emotional Empathy

Abstract

Emotional empathy (EE) is a key component and target in psychiatric nursing education and could be facilitated by psychological resources such as self-compassion (SC) and self-focus (SF). The combined effect of these resources on EE has not yet been analyzed in research. This cross-sectional study conducted in 2019 used cluster analysis to identify groups of nurses divided by SC and SF and compared them based on EE. The sample comprised 572 psychiatric nurses from seven large hospitals in Japan, who were asked to complete a questionnaire that comprised the Japanese version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), the Japanese version of the Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ), and the Emotional Empathy Scale (EES). We identified two clusters based on the data analysis, of which one scored higher than the other in self-criticism, as well as SF, in both aspects of reflection and rumination. In addition, EE was higher in the former than in the latter. These findings suggest that traditional nursing education, which often focuses on reducing self-criticism and rumination, may need to be re-evaluated. While these traits are typically viewed as negative, our study indicates that they could play a role in enhancing EE when combined with reflection. Therefore, it may be beneficial for nursing education to incorporate strategies that foster reflection and encourage acceptance of self-criticism and rumination, rather than solely focusing on their reduction. This approach could help nurses develop greater empathy, an essential skill in psychiatric nursing practice. Educational programs that support this balance between reflection and self-acceptance could enhance both personal and professional growth among nurses, ultimately improving patient care outcomes.

1. Introduction

Empathy, a crucial component of caring and nursing, is divided into two major aspects: cognitive empathy and emotional empathy (EE). Cognitive empathy refers to an individual′s ability to recognize others′ emotions based on appropriate cues. This ability is also referred to as the affective Theory of Mind or affective perspective taking [1, 2]. EE refers to the ability to experience other people’s emotions, even if the perceiver has not experienced the event [2, 3]. This could also be called experience sharing.

Various studies have reported the benefits of empathy skills. In the field of clinical psychology, a meta-analysis by Elliott et al. [4] examined the relationship between therapists’ empathy and outcomes in clients. The results revealed an approximately 9% improvement in therapy outcomes, which was higher than that of other specific treatments. In the field of oncology, a meta-analysis reviewed 55 articles and revealed a stable positive relationship between physician empathy and favorable outcomes in patients [5]. Furthermore, positive effects of empathy on pain, anxiety, functional status, patient safety, physician–patient communication, and satisfaction were observed in healthcare consultants [6–8]. Therefore, empathy skills, which had clinical benefits, should be enhanced by education and/or curricula in schools and/or on-the-job training, especially in psychiatric mental nursing.

Many studies aimed to improve practitioners’ or students’ empathy ability, especially in medical education. A meta-synthesis analysis reviewed 23 qualitative studies and revealed that empathy-based interventions could facilitate both practitioners’ professionalism and a deeper understanding of their patients’ experiences [9]. Tement et al. conducted a systematic review to examine the benefits of psychological intervention via mindfulness and found that it enhances empathy [10]. Patel et al. reviewed 52 studies that examined the effects of curricula that aimed to enhance empathy and found that the majority showed favorable effects, such as interview styles with compassion and telling support, among others [11]. In addition, eligible studies in their review involved the following educational methods: real interactions with actual patients, video recordings of interviews, didactics, small groups, and role-playing. Although educational trials reported success in enhancing empathy, empathy competency reportedly declined year by year, especially in students in school or their trainee phase [12]. Therefore, the development of further effective educational perspectives is required. Although reported as lacking [11], curricula focusing on healthcare providers’ psychological features might be promising components in education for enhancing EE.

Since individual nurses provide psychiatric nursing as a caring tool, their consciousness to the self is crucial. These patterns could play both protective psychological resources for providing care and an adverse role. As a psychological resource for providing care, self-compassion (SC) has received considerable attention. It is a compassionate attitude toward the self, defined by Neff [13] as “being touched by and open to one’s own suffering, not avoiding or disconnecting from it, generating the desire to alleviate one’s suffering and to heal oneself with kindness.” Furthermore, it is thought to be divided into three bipolar subconcepts: self-kindness versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification. This psychological resource was confirmed as a facilitating factor for compassion for others [14, 15] and also against negative emotion and depression [16, 17]. This suggested that these resources are required to provide adequate compassionate nursing without excessive fluctuation in emotion.

Another pattern related to the self is self-focus (SF), the attitude and thinking pattern toward the self [18, 19]. It is thought to have both adaptive and maladaptive aspects, called reflection and rumination, respectively. Reflection is motivated by intellectual curiosity regarding the self and is followed by a better understanding of upsetting events and the acquisition of other perspectives. Rumination is motivated by loss and/or threat and characterized by repetitive negative thoughts rather than productive problem-solving. This attitude is also thought to lead nurses to facilitate or inhibit deeper insights into their interpersonal relationship patterns, which are crucial components for improving caring skills.

SC and SF have several common factors, such as attitudes and thoughts toward the self, and possibly facilitate and inhibit factors that enhance caring skills. Previous studies have examined the effects of both SC and SF on negative affect [20], and our prior work demonstrated that both are related to nursing competency especially skills of the nursing process [21]. However, their effect on EE has not been examined. Given the critical role of EE in psychiatric nursing, it stands as a vital educational object. Therefore, as a step to develop an effective educational strategy for fostering EE, it is imperative to delineate group characteristics based on psychiatric nurses’ levels of SC and SF. Consequently, this cross-sectional study, serving as a secondary analysis of data from our previous publication [21], aimed to clarify the group features of psychiatric nurses via a cluster analysis based on their SC and SF and obtain suggestions for educational strategies.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

Participants were Japanese psychiatric nurses from seven psychiatric hospitals. The research items were originally collected as part of a series of previously published studies [21]. In this study, a portion of the data was reanalyzed as a secondary analysis, following a protocol that was consistent with the original study project. With more than 100 nurses, the seven institutions were selected since representation was thought to be valid.

The paper-based questionnaires were sent to all 823 nurses in the enrolled hospitals from January 2019 to December 2019. If participants agreed to answer this survey, they completed it and sent it to the first researcher within 2 weeks after the questionnaire was in hand by posting the envelope containing the questionnaire by themselves. A total of 638 nurses responded. Among them, 572 responses were analyzed after excluding those with inadequate answers.

Participants could return the materials independently and anonymously, which assured their anonymity and autonomy.

2.2. Study Design

This was a cross-sectional study.

2.3. Measurements

A questionnaire was used that measured four aspects. Since participants were Japanese, all materials were used in Japanese versions.

2.3.1. Demographics

We obtained the following: participants’ gender, age, role, working ward, the last educational background, and experience in nursing and psychiatric nursing.

2.3.2. SC

SC was measured via the Japanese version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). SCS reported that the test-retest reliable coefficient was 0.83 and correlation coefficients associated with self-esteem and trait anxiety as construct validity were 0.56 and −0.56 respectively, indicating a good reliable, valid, and popular tool [22]. The SCS comprised six subscales with three bipolar counterparts: the self-kindness versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification subscales. The former and latter three subscales were recognized as positive and critical aspects of SC, respectively.

Regarding the number of items, the self-kindness and self-judgment subscales had five items each, and the rest had four items. All items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Higher scores indicated a higher feature in each subscale.

2.3.3. SF

SF was investigated using the Japanese version of the Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ) [23]. RRQ reported that Cronbach’s α was 0.90 and the correlation coefficient with private self-consciousness as construct validity was 0.65, indicating good reliability and validity [23]. The RRQ comprised two subscales with 24 items. The rumination subscale assessed the degree of rumination, which was a maladaptive SF aspect motivated by threat and loss. The reflection subscale assessed the degree of reflection, which was an adaptive SF aspect enhanced by intellectual curiosity. Each subscale had 12 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

2.3.4. EE

EE was examined via the Emotional Empathy Scale (EES), which comprised three subscales with 25 items: emotional warmth (10 items), emotional coolness (10 items), and emotional susceptibility (five items) subscales. All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The EES reported that Cronbach’s α for subscales ranged from 0.60 to 0.76 and that the emotional warmth subscale was positively associated with amicableness, the emotional coolness was negatively associated with antisociality, and the emotional susceptibility was negatively associated with motivation, demonstrating good reliability and validity [24].

2.4. Ethical Consideration

Participants were informed that by submitting the questionnaire, they were consenting to participate in the study. As a result, the act of returning the questionnaire was regarded as indicating informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee at the university affiliated with the corresponding author (IRB approval no.: 18118). Furthermore, one of the participating hospitals conducted an ethical review and granted approval, while the other six hospitals indicated that no additional review was necessary due to prior approval by the university’s ethics committee.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

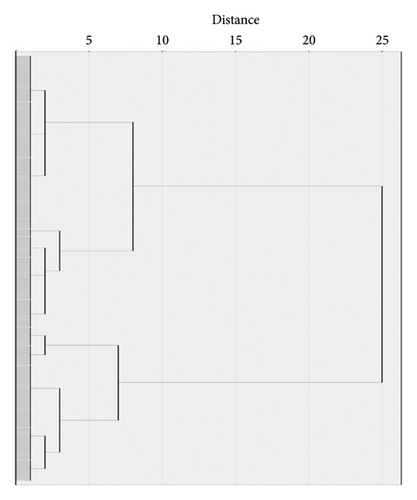

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 23 with a significance level of 5%. Reliability coefficients were calculated for all scales used. We performed a cluster analysis with both squared Euclidean distance to calculate the similarity between individuals and Ward method to calculate similarity between clusters based on subscale scores in both the SCS and RRQ. In addition, the number of clusters was determined based on the dendrogram made via the above calculations and interpretability.

Subsequently, the EES scores and participants’ demographics were compared between the clusters.

3. Results

We analyzed data from the 572 returned questionnaires. Demographics are shown in Table 1. Participants’ average age was 42.0 ± 11.6 years old, 84.4% of their role was staff nurse, and 40.9% of them worked in chronic care ward. As for the last educational background, 69.9% graduated from vocational school. Cronbach’s α for all subscales in the SCS, RRQ, and EES ranged from 0.671 to 0.902 (Table 2).

M n |

SD % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 200 | 35.0% |

| Female | 372 | 65.0% |

| Age | 42.0 | 11.6 |

| Role | ||

| Manager | 83 | 14.5% |

| Staff nurse | 483 | 84.4% |

| Unclear | 6 | 1.1% |

| Ward | ||

| Super acute care | 53 | 9.3% |

| Acute care | 98 | 17.1% |

| Chronic care | 234 | 40.9% |

| Physical concomitant care | 38 | 6.6% |

| Dementia care | 69 | 12.1% |

| Outpatient care | 28 | 4.9% |

| Day care center | 12 | 2.1% |

| Other | 32 | 5.6% |

| Unclear | 8 | 1.4% |

| The last educational background | ||

| Licensed practical nurse’ school | 65 | 11.4% |

| Vocational school | 400 | 69.9% |

| Junior college | 31 | 5.4% |

| University | 37 | 6.5% |

| Graduate school | 4 | 0.7% |

| Unclear | 35 | 6.1% |

| Experience in psychiatric nursing (years) | 12.2 | 9.8 |

| Experience in nursing (years) | 17.6 | 11.3 |

| Total | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 572) | (n = 207) | (n = 365) | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Self-compassion | |||||||

| SCS self-kindness (α = 0.829) | 14.5 | 3.5 | 14.5 | 4.1 | 14.6 | 3.1 | 0.718 |

| SCS common humanity (α = 0.701) | 11.3 | 2.9 | 11.5 | 3.4 | 11.2 | 2.6 | 0.292 |

| SCS mindfulness (α = 0.724) | 12.2 | 2.6 | 12.1 | 3.1 | 12.2 | 2.3 | 0.745 |

| SCS self-judgment (α = 0.844) | 15.7 | 3.9 | 17.9 | 4.0 | 14.5 | 3.2 | < 0.001 |

| SCS isolation (α = 0.732) | 11.3 | 3.1 | 12.9 | 3.2 | 10.5 | 2.7 | < 0.001 |

| SCS over-identification (α = 0.780) | 13.3 | 3.1 | 15.5 | 2.6 | 12.1 | 2.6 | < 0.001 |

| Self-focus | |||||||

| RRQ rumination (α = 0.902) | 38.4 | 8.2 | 46.3 | 5.3 | 34.0 | 6.0 | < 0.001 |

| RRQ reflection (α = 0.824) | 34.7 | 6.2 | 38.3 | 6.2 | 32.6 | 5.2 | < 0.001 |

| Emotional empathy | |||||||

| EES emotional warmth (α = 0.737) | 47.6 | 7.1 | 49.6 | 7.0 | 46.4 | 7.0 | < 0.001 |

| EES emotional coolness (α = 0.799) | 32.3 | 7.7 | 31.9 | 7.8 | 32.6 | 7.6 | 0.272 |

| EES emotional susceptibility (α = 0.671) | 21.2 | 4.3 | 22.8 | 4.7 | 20.2 | 3.8 | < 0.001 |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age | 42.0 | 11.6 | 41.0 | 10.8 | 42.6 | 12.0 | 0.110 |

| Experience in psychiatric nursing (years) | 12.2 | 9.8 | 10.8 | 8.7 | 13.0 | 10.4 | 0.012 |

| Experience in nursing (years) | 17.6 | 11.3 | 16.3 | 10.8 | 18.3 | 11.6 | 0.037 |

Based on interpretability of the dendrogram (Figure 1), we estimated that a 2-cluster solution was adequate. Table 2 presents the scores of both the clusters.

Regarding all subscales in both the SCS and RRQ, scores of Cluster 1 were higher than those of Cluster 2 in all three critical subscales of the SCS and both subscales of the RRQ (p values < 0.001). However, scores of the three positive subscales of the SCS did not differ, which indicated that psychiatric nurses who belonged to Cluster 1 had characteristics of higher self-criticism rumination and also reflection compared to nurses in Cluster 2. Therefore, Cluster 1 was named as self-criticism and rumination with higher reflection, and Cluster 2 was not excessive attention toward the self.

Regarding the EES, Cluster 1 showed significantly higher scores than Cluster 2 in both the emotional warmth and susceptibility subscales (p < 0.001).

Regarding demographics, significant differences were observed in nursing and psychiatric nursing experiences. However, no age differences were observed. Nursing and psychiatric nursing experience in Cluster 1 were 195.0 ± 129.7 and 130.0 ± 104.6 months, respectively, which was shorter than 219.7 ± 138.9 and 155.7 ± 124.3 months, respectively, in Cluster 2 (p = 0.037; p = 0.033).

4. Discussion

This cross-sectional study investigated the underlying clusters based on SC and SF and found two clusters. Cluster 1 showed higher negative aspects of SC and SF and positive aspects of SF compared to Cluster 2. Furthermore, emotional warmth and susceptibility were higher in Cluster 1 compared to in Cluster 2. These findings implied that high self-criticism was accompanied by high both positive and negative aspects of SF. In addition, those who shared these psychological features tended to show more emotional warmth and susceptibility.

4.1. Accompanying Self-Criticize and SF

Self-criticism, a negative aspect of SC, was associated with negative psychological features, such as rumination, and not positive psychological features. Hasking et al. investigated undergraduate students and found a negative association between the total SCS and rumination scores [25]. Hodgetts et al. found that rumination had a negative association with self-criticism and not with positive aspects of SC [26]. These previous findings were concordant with our findings, which revealed no significant differences in the positive components of the SCS between Clusters 1 and 2. This could be due to two reasons. First, the absolute correlation coefficient value of negative components in the SCS with mental issues tended to be higher than that of positive components. Muris and Petrocchi conducted a meta-analysis that reviewed 18 studies to synthesize the correlation coefficients of all the subscales in the SCS to psychopathology and compared the figures between the positive and negative components of the SCS. They found that the absolute correlation coefficients in all the negative components were higher than those in the positive components [27]. Second, the degree of correlation between the positive and negative components in the SCS was lower in Japan than in European countries [28]. This indicated that higher positive components in the SCS were not necessarily accompanied by lower negative components. Therefore, only self-criticism may differ between the clusters.

However, this association may be modified by rumination type. A longitudinal study investigated French parents and explored the association between SC and two types of rumination: abstract and concrete [29]. They found that the association patterns were adverse. Higher concrete and abstract rumination were associated with better and worse SC, respectively. The RRQ, which was used in this study, had several items that might be recognized as concrete rumination, such as “I think I always recall what I said and done recently in my mind.” Therefore, rumination and self-criticism were accompanied.

4.2. Accompanying Self-Criticize and Rumination With EE

Contrary to our expectations, higher negative components of the SCS were accompanied by higher empathy. Marshall et al. investigated adolescents in grades 9 to 12 and found that a lower total score on the SCS-short form was associated with higher affective empathy in all grades, which indicated a stable relationship pattern [30]. However, several studies have attempted to clarify the relationship between self-compassion and emotional intelligence—defined as the ability to regulate one′s emotions—and have found that higher levels of positive components and lower levels of negative components of SC are associated with greater emotional intelligence [15, 31]. These differences in our results might be related to the average SCS levels in the participant groups. The scores of previous samples were relatively higher and lower in the positive and negative components, respectively, than in those in our sample. Scores in the positive components in the SCS were reported as 45.5 and 39.5 [15, 31], respectively, whereas our score was 38.1. Conversely, negative components were reported as 32.5 and 41.5 [15, 31], respectively, although our score in Cluster 1 was 46.3. Therefore, this trend could be a characteristic feature of psychiatric nurses in Japan who had relatively low SC at baseline.

Rumination, a negative aspect of SF, was not related to empathy or consciousness toward others. Liu et al.’s cross-sectional study investigated university students and found that rumination was not significantly associated with EE [32]. Paleari et al. conducted a longitudinal study on married adults and found that rumination at baseline did not correlate with empathy at baseline or follow-up [33]. However, their instrument for empathy was only three items and assessed empathy toward family. Conversely, Boyraz and Waits’s longitudinal study investigated university students in the US and found a positive cross-sectional association between rumination and EE and that higher rumination at baseline predicted higher empathy during the follow-up period [34]. Furthermore, the effects of deliberate rumination on posttraumatic growth were observed among registered nurses experienced in caring for patients with COVID-19 [35] and intensive care unit (ICU) nurses [36]. The findings of a concomitant pattern of both rumination and empathy could be related to the features of both the RRQ and psychiatric nurses. For items on the RRQ rumination subscale, deliberate rumination was assessed for several items, for example, “I tend to think about happenings around me repetitively for a long time” and “I often recall how I acted in the previous situation in my mind.” This implied that this subscale measured a part of deliberate rumination. In addition, psychiatric nurses, especially Japanese nurses, tended to deliberate recall to be aware of their own interpersonal relationship patterns and enhance their caring skills as a responsibility of psychiatric nursing. Therefore, a trend between rumination and empathy was found.

Hence, a higher extent of attention to the self, even a negative attitude, might be related to higher EE.

4.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, our study employed a cross-sectional design. Therefore, whether this cluster’s feature would remain stable across time was unclear. To clarify the degree of certainty of this cluster structure, a future longitudinal study is required. Second, this investigation was conducted in only one country, Japan. A large-scale investigation highlighted that levels of self-compassion vary across different cultures [28]. Thus, cluster structures in nurses across countries should be compared to conclude whether our result is a universal or unique Japanese structure. Third, this study employed self-reported questionnaires, which may have been subject to social desirability bias, as participants might have provided responses they perceived as socially acceptable. To mitigate this limitation, future research should incorporate objective measures to enhance data reliability.

4.4. Implications for Nursing Practice

This cross-sectional study used a cluster analysis and showed that higher self-criticism, reflection, and rumination were accompanied by higher EE. In general, nursing education aimed to reduce excessive self-criticism and rumination. However, our study revealed that even if self-criticism and rumination levels were relatively high, empathy ability could be enhanced. Although the above negative components were thought to be adverse aspects, they could facilitate posttraumatic growth [35], which could be followed by empathy skills. In addition, a randomized control trial by Dunn and Luchner confirmed that even in participants with high self-criticism, reflection intervention could reduce negative emotions; however, rumination interventions did not [20]. Furthermore, a preliminary randomized control study that examined the effect of an educational intervention aimed to stimulate SC found that the intervention increased not only SC and reflection but also rumination [37]. Conversely, education focused on reflection as an element of educational strategies was most effective among other combinations of education [38]. Therefore, while traditional educational strategies have focused on reducing excessive rumination and self-criticism, recent perspectives suggest that these negative components—when present at moderate levels—may actually support the development of empathy if learners are guided through structured reflection in educational settings. This suggested that nursing education for empathy was favorable to facilitate reflection and acceptance of their self-criticism and rumination pattern.

5. Conclusion

Although clarifying patterns of attitudes toward self, including SC and SF, is crucial to enhancing nurses’ empathy skills, the association between these factors was previously unknown. Therefore, this cross-sectional study aimed at examining the patterns and clarified the structure of the clusters based on both the SCS and SF in Japanese psychiatric nurses and found a two-cluster solution: Nurses who exhibited higher scores in both the negative components of self-compassion and both aspects of self-focus, as well as higher emotional empathy, differed from those with lower scores in these areas. Traditionally, nursing education has recommended methods to correct excessive self-criticism. However, the findings of this study suggest that self-criticism and ruminating may also enhance nurses’ empathic abilities, and nursing education needs to focus on the ability to self-criticize and ruminate.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate all participants and staff working at the registered hospitals.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are restricted by the ethics board of Niigata University of Health and Welfare in order to protect patient privacy. Data are available from Yusuke Kurebayashi ([email protected]) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. Research data are not shared.