Happiness and Sacredness: A Qualitative Study on Doctoral Students’ Well-Being and Academic Career Choice

Abstract

Background: Understanding the impact of doctoral students’ well-being on their academic career choices is essential for examining how emotional and psychological factors influence career decision-making. This is especially important as students face increasing pressure to transition out of academia, a shift that has broader implications for their professional development and for the future of higher education.

Purpose: This study explores the relationship between doctoral students’ well-being and their academic career choices.

Design and Method: A qualitative approach was employed, involving in-depth interviews with 37 doctoral students from prestigious research universities in China. Each interview lasted between 90 and 120 min. The data were analyzed using a thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke’s framework.

Findings: The results reveal that the experience of well-being influences doctoral students’ academic career choices. Doctoral students with high levels of both hedonic well-being (HWB) and eudaimonic well-being (EWB) are more likely to demonstrate a strong commitment to an academic career. Those with high HWB but low EWB tend to view academia as a pragmatic livelihood choice. Conversely, students with low HWB but high EWB may experience indecision and ambiguity about their career direction. Finally, when both HWB and EWB are low, doctoral students are more likely to actively choose to leave academia.

Practice Implications: This study proposes strategies to enhance doctoral students’ well-being through collaborative research, balanced authority in student–supervisor relationships, and targeted psychological and professional development.

1. Introduction

Doctoral graduates represent the highest level of educational attainment and are primarily trained to conduct original research. As governments continue to increase funding for doctoral education, the expansion of doctoral programs seems likely to persist, with the goal of enhancing national competitiveness and fostering talent pools in an increasingly globalized and competitive environment [1]. Doctorate holders are widely regarded as key contributors to the knowledge economy and national innovation systems, and the career paths they choose after graduation have become a subject of considerable interest and concern [2, 3].

Doctoral education traditionally serves as a preparatory stage in which students decide whether an academic career, often envisioned as a tenure-track faculty position, is the right path for them, with the common assumption at research-intensive institutions that this stage will naturally lead to a faculty position and an academic career [4]. With limited positions available in the academic labor market, doctoral graduates’ employment is increasingly diversified across various sectors worldwide [5, 6], and an increasing number of doctoral students are facing pressure to transition out of academia [7]. As a resource for faculty members, doctoral graduates play an important role in advancing the future objectives of higher education [8]. Consequently, the academic career choices made by doctoral students are not only pivotal for their own professional development but also have significant implications for the continued innovation within academia and the broader higher education landscape.

In higher education, doctoral students are often identified as a group with volatile well-being at work [9, 10]. Well-being is a complex construct that concerns optimal experience and functioning and is “an overarching term that encapsulates an individual’s quality of life, happiness, satisfaction with life and experience of good mental and physical health” [11–13]. Previous research has established a correlation between emotions and career decision-making [14, 15]. However, compared to the other professional groups, the relationship between doctoral students’ perception of well-being and their career choices has been relatively underexplored. Well-being can significantly influence doctoral students’ choice of and identification with an academic career, as well as their desire for academic freedom, career achievements, and ability to manage professional stress.

Understanding how well-being influences doctoral students’ career decisions is critical for addressing the challenges they face and fostering innovation within higher education. This study investigates the impact of well-being on doctoral students’ academic career choices, focusing on two key components of well-being: hedonic well-being (HWB) and eudaimonic well-being (EWB). By examining these dimensions, this study seeks to provide new insights into the complex interplay between well-being and career decision-making among doctoral students.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Understanding Well-Being and Doctoral Students’ Well-Being

Well-being is a multifaceted concept with no universally accepted definition [16]. The recognition of well-being is considered to be rooted in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of health, which describes health not just as the absence of disease or infirmity, but as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being [17]. Current research on well-being is based on two general perspectives [11]: the HWB, which defines well-being in terms of pleasure attainment and pain avoidance, and the EWB, which emphasizes meaning and self-realization, defining well-being by the extent to which a person is functioning at his or her full potential and leads a life in accordance with his or her true self [18]. Most research within the hedonic perspective has used assessment of subjective well-being (SWB), which consists of three components: the presence of pleasant emotions, the absence of unpleasant emotions, and personal judgments about satisfaction, together often summarized as happiness [19, 20]. EWB is grounded in authentic living, involving the pursuit of goals and activities that reflect an individual’s true self and align with their core values, with a focus on the integrity and meaningfulness of these pursuits [18, 21]. From the eudaimonic perspective, Ryff and Keyes [22] proposed psychological well-being (PWB) as distinct from SWB and introduced a multidimensional approach to measuring it, including autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. The self-determination theory (SDT) defines well-being as the fulfillment of three basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness [23, 24]. While both perspectives are distinct and stem from different philosophical foundations, they nonetheless overlap [25]. Seligman [26] incorporated components of both HWB and EWB and presented the PERMA model, which explains well-being as a combination of positive emotion, engagement (flow), positive relationships, meaning, and achievement.

Most of the current research studies on doctoral students’ well-being adopt a hedonic perspective, which primarily examines their positive or negative emotions. The quality of mentorship has a significant impact on doctoral students’ motivation, satisfaction, and stress levels, leading to either a positive or negative effect on their well-being [13, 27]. Positive experiences during doctoral studies, such as a sense of productivity, self-efficacy, and feelings of empowerment, can support well-being [28, 29]. However, the doctoral program is often viewed as negatively impacting students’ well-being, with the existing research highlighting higher stress levels and mental health challenges among doctoral students [30, 31]. Morrison Saunders et al. [32] proposed that all doctoral students experienced emotional swings and negative emotions were most likely in the middle phase and were often associated with data collection. Doctoral students frequently encounter negative emotions and significant distress due to various factors, including constant peer pressure, frequent evaluations, low status, heavy workload, financial difficulties, and the pressure to publish. Additional challenges include the need for active participation in scholarly communities, lack of permanent employment, and uncertainty about their future career prospects [9, 33–36].

2.2. Doctoral Students’ Academic Career Choice

The appeal of academic careers is declining, with an increasing number of doctoral students opting for nonacademic positions, thus deviating from the traditional academic trajectory [37]. The inability of academia to retain top talent has become a growing concern [38]. Existing research on doctoral students’ career choices has primarily focused on internal factors such as gender, nationality, age, academic interests, and intrinsic motivation, as well as external factors such as academic discipline, mentorship, and the academic labor market.

Among the external factors, the growing number of doctoral graduates combined with the shrinking availability of tenure-track positions has created a significant imbalance in the academic job market, making it increasingly difficult for doctoral students to secure academic careers [39]. Additionally, the highly competitive tenure-track system [40] and uncompetitive academic salaries [41] further exacerbate these challenges, diminishing the attractiveness of academic careers for many doctoral students. Beyond structural barriers, doctoral students’ career choices are heavily influenced by socialization factors such as mentorship, connections within the academic community, and their academic discipline. A strong mentor–student relationship can provide access to tacit knowledge [42], enhance self-efficacy, and cultivate an interest in academic careers [4]. In fact, students who report higher satisfaction with their supervisors’ guidance are more likely to pursue academic roles [4]. Furthermore, building social ties within the scientific community during doctoral studies strengthens students’ academic identity, effectively encouraging them to engage in academic careers [43]. Disciplinary differences also play a crucial role in shaping career decisions. Specifically, doctoral students in fields closely tied to industry, such as business, are more inclined to pursue nonacademic roles or entrepreneurial ventures. In contrast, those in the humanities and social sciences often exhibit a stronger preference for academic careers [44].

Among internal factors, previous research has highlighted the influence of age, gender, academic interests, and intrinsic motivation on doctoral students’ academic career choices. In terms of personal characteristics, older doctoral students are more likely to pursue academic careers [45]. Compared to men, women are often more inclined toward academic roles due to their perceived stability and lower risks [45, 46], but they are also more likely to face obstacles related to marital responsibilities [47]. Family socioeconomic background also plays a role. Doctoral students from rural, low-income families tend to favor academic careers, viewing them as a path to upward mobility [41]. Intrinsic motivation is particularly important in the pursuit of academic careers. Additionally, intrinsic motivation is equally critical in driving academic career choices [38]. Doctoral students with stronger academic interests and a pronounced “taste for science” are more likely to choose academic careers [48]. Despite these insights, limited research has explored the impact of doctoral students’ well-being on career choices. One notable study by Hunter and Devine found that around one-third of doctoral students intended to leave academia after completing their PhD. This intention was strongly correlated with emotional exhaustion experienced during the doctoral process, highlighting the impact of well-being on career decisions. This intention was notably higher among students in hard-applied and soft-applied disciplines [49].

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Academic Vocation as a Calling: Weber’s Perspective

Traditionally, pursuing an academic career is often seen as driven by strong intrinsic motivation rather than external material rewards. Max Weber articulated this perspective in his 1919 lecture Science as a Vocation (Wissenschaft als Beruf), where he introduced the concept of academic work as a “vocation” (Beruf). Rooted in the Protestant ethic, this notion bridges the religious and secular meanings of a “calling,” imbuing academic pursuits with both spiritual intensity and pragmatic purpose [50]. Weber ([51], p. 134) described academic life in the early 20th-century Germany as “a mad hazard,” emphasizing the years of dedication required before a young scholar could even hope to establish a stable career. The rigorous selection process and uncertain prospects, he argued, made an inner calling essential to endure the inevitable imperfections of one’s scientific work. According to Weber, scholars must choose academia driven by intrinsic motivation rather than external factors. Without what he termed the “strange intoxication, ridiculed by every outsider” ([51], p. 135), a person lacks the vocation for science and should pursue a different career. For Weber ([51], p. 135), “nothing is worthy of man as man unless he can pursue it with passionate devotion.”

Weber’s emphasis on intrinsic motivation underscores his view that external factors such as salary or the difficulty of achieving success are secondary considerations in the choice of an academic career. For him, the true academic vocation requires a profound internal drive and a willingness to embrace the uncertainties and challenges inherent in scholarly life. This notion of academic calling has had a profound and lasting impact. It shaped the professional ethos and devoted attitude of the 20th-century German scholars, who embraced solitude and intellectual rigor. Furthermore, Weber’s framework has become a foundational assumption for contemporary research on academic careers, influencing how we understand the motivations and commitments underlying scholarly work [52–54].

3.2. “Absorbing Errand” of Academic Career: Clark’s Theory

Similar to Max Weber’s insights, Burton R. Clark introduced the concept of the “absorbing errand” to highlight the unique appeal of academic career choice. Clark ([55], p. 272–275) identified three core principles underlying the academic profession: the hegemony of knowledge, dualities of commitment, and the absorbing errand. Together, these principles sustain the rationale and stability of the academic vocation. The “absorbing errand” represents the profound moral significance and enduring sense of purpose embedded in academic work. It embodies the notion that “true happiness consists of getting out of oneself” ([55], p. 272) by offering intellectually engaging and long-term assignments that inspire and motivate. Clark argued that when the academic profession is reduced to a routine career, material rewards become the primary factor in career choice. However, when viewed as an absorbing errand, academic work—both teaching and research—acquires intrinsic meaning, fostering a deep sense of fulfillment and accomplishment.

Creating an academic environment that provides individuals with a strong sense of purpose and value is therefore crucial. Such an environment not only enhances the personal satisfaction of those within the profession but also plays a pivotal role in attracting and retaining talent over the long term ([55], p. 274). By framing academic work as an absorbing errand, institutions can inspire commitment and ensure the sustainability of the academic profession.

3.3. The Connection Between Weber and Clark’s Theories and the Concept of Well-Being

The classic theories of Max Weber and Burton R. Clark on the unique nature of academic careers seem to converge on a shared idea: individuals do not choose academic careers solely based on material rewards or risk assessments but are driven by intrinsic motivation. Weber referred to this as “the inward calling,” while Clark described it as “true happiness.” Both of them used terms such as “passion,” “satisfaction,” and “strange intoxication,” to capture the distinct sense of fulfillment derived from academic career itself. From this perspective, the experiences described by Weber and Clark align closely with the concept of well-being.

Weber’s notion of “vocation” (Beruf) and Clark’s “absorbing errand” correspond to the EWB dimensions of “the pursuit of goals” and “purpose in life,” emphasizing the internal drive that propels individuals toward academic careers. Similarly, Weber’s “strange intoxication” and “passionate devotion,” along with Clark’s “true happiness” and “sense of fulfillment and accomplishment,” align with HWB, particularly the presence of positive emotions, and with EWB dimensions such as autonomy, personal growth, meaning, and achievement. Table 1 illustrates the relationships discussed.

| Theoretical dimension | Weber’s “vocation” | Clark’s “absorbing errand” | Corresponding well-being type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic motivation | Vocation (Beruf); the inward calling | Absorbing errand; the profound moral significance and enduring sense of purpose | EWB: The pursuit of goals; the purpose in life |

| Emotional experience | Strange intoxication; passionate devotion | Satisfaction; true happiness; the sense of fulfillment and accomplishment |

|

Overall, Weber and Clark’s theories align more closely with the dimensions of EWB, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of EWB may be more likely to pursue and remain committed to academic careers. Building on these foundational insights, this study applies Weber’s and Clark’s frameworks to examine doctoral students’ motivations and experiences, offering critical perspectives on their well-being and academic career choices.

4. Method

This study aims to explore how well-being influences doctoral students’ academic career choices using a qualitative research methodology, which is effective for understanding how individuals or groups interpret and ascribe meaning to social or human issues through assumptions and interpretive/theoretical frameworks [56].

Interview data were collected from 37 doctoral students at prestigious research universities in China, comprising 19 males and 18 females (see Table 2). Among these participants, 19 were from the natural sciences and engineering, and 18 were from the humanities and social sciences. Purposive sampling was used to select doctoral students who considered academic careers as a potential career option, while ensuring diversity across disciplines. Participants reflected on various aspects of their career choices and well-being through semistructured interviews, which lasted 90–120 min and were digitally recorded for transcription. Interview questions included: How do you perceive an academic career? Will you choose an academic career in the future? What preparations have you made for pursuing an academic career? What experiences during your doctoral studies have made you feel happy? What experiences during your doctoral studies have made you feel unhappy? Has your sense of well-being influenced your choice of an academic career?

| Interviewee | Discipline | Gender | Year of doctoral program |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Chinese Language and Literature | Female | Fourth |

| F2 | Medicine | Female | Fourth |

| F3 | Education | Female | Fourth |

| F4 | Education | Female | Fourth |

| F5 | Sociology | Female | Fifth |

| F6 | Foreign Languages and Literature | Female | Fourth |

| F7 | Computer Science | Female | Third |

| F8 | Biology | Female | Third |

| F9 | Education | Female | Second |

| F10 | Education | Female | Second |

| F11 | Biology | Female | Fourth |

| F12 | History | Female | First |

| F13 | Engineering | Female | Fourth |

| F14 | International Relations | Female | Second |

| F15 | Archeology | Female | Third |

| F16 | Law | Female | Second |

| F17 | Philosophy | Female | Fourth |

| F18 | Environmental Engineering | Female | Third |

| M1 | Education | Male | Third |

| M2 | Chemistry | Male | Third |

| M3 | Materials Science and Engineering | Male | Third |

| M4 | Materials Science and Engineering | Male | Third |

| M5 | Geology | Male | Fourth |

| M6 | Biology | Male | Third |

| M7 | Computer Science | Male | Third |

| M8 | Philosophy | Male | Third |

| M9 | Physics | Male | Fifth |

| M10 | Physics | Male | Third |

| M11 | Education | Male | Fourth |

| M12 | Computer Science | Male | Third |

| M13 | Chemistry | Male | Third |

| M14 | Philosophy | Male | Fourth |

| M15 | Computer Science | Male | Fourth |

| M16 | Management | Male | Fourth |

| M17 | Engineering | Male | Fourth |

| M18 | Politics | Male | Fourth |

| M19 | Computer Science | Male | Fifth |

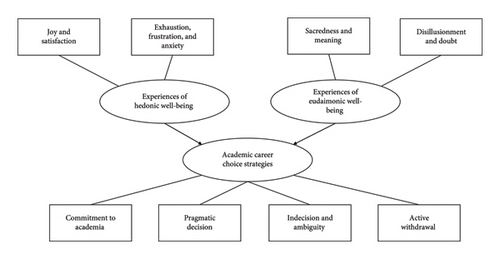

A thematic analysis approach was applied, which is a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data, and it minimally organizes and describes data set in detail [57–59]. This study followed Braun and Clarke’s six phases of thematic analysis framework to ensure rigor and transparency [57]. First, the research team was familiarized with the data by transcribing and thoroughly reading the transcripts while noting initial ideas and patterns. Next, initial codes were generated by systematically identifying and categorizing meaningful data segments across the dataset, using both inductive and deductive approaches. Codes such as “hedonic well-being” and “eudaimonic well-being” emerged during this stage. These codes were organized into potential themes, with relevant data gathered under each theme. Themes were then reviewed for coherence and relevance to both the coded data and the overall dataset. Each theme was refined and clearly defined to capture its core essence, with interconnections visualized in a thematic map (Figure 1). The findings were reported using vivid, representative quotes, linked back to the research questions, and contextualized within the existing literature.

Trustworthiness was ensured through investigator triangulation, where at least two researchers independently analyzed each transcript and resolved disagreements through discussion. Member checking was conducted by sharing findings with selected participants to validate interpretations.

Ethical guidelines were rigorously followed to protect participants’ rights and confidentiality. Informed consent was obtained after participants were briefed on the study’s purpose, procedures, and potential risks, with their right to withdraw emphasized. Data confidentiality was safeguarded through anonymization, using pseudonyms during transcription and reporting. To address potential biases in translating interviews from Chinese to English, the researcher collaborated with a bilingual expert to ensure accuracy and cultural sensitivity.

5. Findings

This research draws on the experiences of 37 doctoral students who had considered an academic career as their future profession during their doctoral studies. They encountered a range of experiences, both positive and negative, that influenced their well-being. In turn, their well-being impacted their strategies for choosing an academic career.

5.1. Experiences of Doctoral Students’ HWB

5.1.1. Positive Experiences: Joy and Satisfaction

Doctoral students’ HWB is significantly influenced by their experiences of joy and satisfaction in academic activities. These positive feelings typically stem from several factors, including the development of academic competence, research accomplishments, and recognition from others.

“After completing my doctoral studies, I recognized a significant improvement in my academic abilities. This perception brought me a strong sense of joy and fulfillment.” (M10, Physics)

“I think I was the happiest when my first paper was published, very satisfied, because I felt that I had made a contribution to this field.” (M9, Physics)

“When I was conducting research, I experienced great joy when, after intense reflection, a highly creative idea suddenly sparked in my mind.” (M13, Chemistry)

“Genuine happiness comes from making meaningful contributions to research, rather than from the amount of resources one receives or the quantity of papers produced.” (M2, Chemistry)

“Receiving academic awards … not only sparked my greater interest in research, but also gave me a strong sense of motivation. I also felt a significant sense of accomplishment from being recognized by the academic community.” (M5, Geology)

5.1.2. Negative Experiences: Exhaustion, Frustration, and Anxiety

Doctoral students often experience negative emotions such as exhaustion, frustration, and anxiety, which undermine their HWB. These feelings are typically driven by factors such as excessive academic workloads, poor work–life balance, research setbacks, and uncertainties about career prospects.

“I work in the lab for 16 hours every day and can only take two weeks off all year. It’s truly exhausting.” (F8, Biology)

“Can you believe it? My peers and I sometimes work for 48 hours straight.” (F2, Medicine)

The academic work–life imbalance, along with the resulting decline in quality of life, negatively affects doctoral students’ HWB. The demands of academic research often conflict with personal life, leading many students to sacrifice social activities and personal interests. When asked about their work–life balance, all the interviewed doctoral students indicated that their personal lives were severely compromised, with some even describing their “personal life as synonymous with academic life” (M13, Chemistry). This imbalance forces students to neglect personal interests and relationships, further diminishing their sense of happiness.

“Research inevitably involves failure. Frequent setbacks made me realize that success is a privilege for a few, while failure is the norm in research.” (F8, Biology)

“When I am writing papers, I often go through prolonged periods of self-doubt and frustration, which makes me question my academic abilities and self-worth.” (F17, Philosophy)

“In the future, we will also face the ‘publish or perish’ dilemma. Young faculty members must continuously produce research outputs after being hired, or they risk job insecurity.” (F3, Education)

5.2. Experiences of Doctoral Students’ EWB

5.2.1. Positive Experiences: Sacredness and Meaning

Doctoral students’ belief in the sacred and meaningful nature of academic careers is a key source of their EWB. For these students, academia is not just a career choice but also a life mission and a spiritual pursuit. This commitment is rooted in a belief in the inherent value of academia and is often closely tied to their perceptions of advanced knowledge, the identity of being an educator, as well as concepts such as academic freedom and fairness.

“The nobility and sanctity of academia lied in its pursuit of truth.” (M5, Geology)

“Academia was not only a means of transmitting knowledge, but also a tool for bearing social responsibility and driving societal progress.” (M11, Education)

“Faculty members not only impart knowledge, but also serve as guides in shaping students’ lives.” (M6, Biology)

“Academia offers individuals the opportunity to immerse themselves in the pursuit of knowledge, without being disturbed by external interference, thereby providing a sense of intellectual freedom and spiritual fulfillment.” (M1, Education)

“I’m not good at socializing and prefer to gain recognition in academia through my professional knowledge and achievements. I believe this can be achieved through hard work.” (M2, Chemistry)

5.2.2. Negative Experiences: Disillusionment and Doubt

Disillusionment and doubt about academic values diminish doctoral students’ EWB. When doctoral students recognize the significant gap between the idealized academic career and the harsh realities of complexity, inequality, and pressure, they experience cognitive dissonance, self-doubt, and psychological struggle as they pursue their academic ideals.

“The academic field presents a pyramid-like hierarchical structure, where most scholars in the lower and middle tiers face survival struggles and workplace pressures.” (F16, Law)

“In academia, there is ‘camp-building’ and ‘clique-forming’; it’s not just about doing research; it also involves complex interpersonal interactions.” (F3, Education)

“The evaluation standards and requirements in our field are becoming increasingly stringent. This overly utilitarian and standardized academic environment has suppressed my own ideals and aspirations.” (F6, Foreign Languages and Literature)

“I think that the academic profession has become constrained by rules and regulations, no longer as pure and idealistic as I once envisioned.” (M1, Education)

5.3. Academic Career Choice Strategies Influenced by Well-Being

Doctoral students with different perceptions of the HWB and EWB adopt different strategies in choosing academic careers.

5.3.1. Commitment to Academia

“Academia is my lifelong career. I don’t care about achieving social status or fame through an academic profession; I only care about how far I can go on this academic journey. I am willing to give up other things for it.” (F4, Education)

“For the sake of my academic career, I am willing to forgo marriage and having children.” (M2, Chemistry)

5.3.2. Pragmatic Decision

“Research doesn’t really align with my personal interests, but considering other factors, academia is the best choice for me at this stage. However, it’s only temporary—just a way to make a living. If I gain more work experience, I might consider other options.” (M6, Biology)

“I don’t think academia provides me with any spiritual meaning, but it’s the only thing I can do. I can write and publish, but it’s just a job. What else can I do? I’m not competitive enough to work in industry.” (F15, Archaeology)

5.3.3. Indecision and Ambiguity

“I doubt whether my abilities are suited for an academic career, but I find meaning in doing academic work. Maybe I’ll take a job that’s close to being a university lecturer for now, and see if I can return to academia later.” (F1, Chinese Language and Literature)

5.3.4. Active Withdrawal

For doctoral students who experience both low levels of HWB and EWB, choosing to actively withdraw from academia is a common strategy. These students could not gain positive emotional experiences or cognitive feedback from academic activities, and they do not believe in the meaning and value of an academic career. As a result, they view leaving academia as a proactive choice. These students do not exit academia due to failure, but rather because they lack intrinsic identification with the academic profession, are disappointed by the high investment and low returns it entails, and seek better quality of life and career development. When the intrinsic motivational mechanisms of an academic career are greatly diminished, the likelihood of doctoral students turning to other industries or career paths increases.

6. Discussion

This study engages with the classic theories of Max Weber and Burton R. Clark on the academic profession. Both Weber and Clark suggest that individuals in the academic profession are typically depicted as being deeply motivated by internal drives, focusing primarily on the core activities of teaching and research. For individuals, experiencing passion, a sense of self-worth, and fulfillment in academic careers is critical to sustaining long-term engagement in academia. However, recent studies have highlighted that the academic profession is undergoing profound changes that are affecting academics’ identity work [52, 60, 61]. Consequently, it is uncertain whether intrinsic motivation and EWB remain pivotal in the choice of academic careers today.

The findings reveal that doctoral students’ belief in the sacred and meaningful nature of academic work serves as a significant source of their EWB. Higher levels of EWB, in turn, increase their likelihood of pursuing academic careers. For instance, doctoral students with low HWB but high EWB often face a complex decision-making process shaped by external pressures. Nonetheless, their belief in the inherent value of academic work frequently brings them back to their academic pursuits. Conversely, doctoral students with high HWB but low EWB are more likely to view an academic career pragmatically, as a solution for livelihood. For these students, the prospect of more attractive opportunities outside academia increases the likelihood of abandoning academic pursuits.

These findings align with Clark’s assertion that the distinctiveness of the academic profession lies in its “absorbing errand,” which plays a crucial role in the long-term recruitment and retention of talent. As Clark warns, “When the errands run down, the demons disappear, and talented persons’ search for other fascinations and enchantments” ([55], p. 274). This study underscores that, even amid significant transformations in academia, the traditional view of an academic career as a calling continues to hold relevance. The enduring belief in the mission of academic work remains a vital factor in shaping career choices within the academic profession.

This study contributes to the literature by clarifying whether doctoral students’ well-being is associated with their academic career choices. Previous research on the relationship between well-being and career choice has primarily focused on the impact of career choice on well-being [15, 62, 63]. In contrast, this study demonstrates that doctoral students’ experiences of well-being also influence their career choices. The study further reveals the important role played by different components of well-being in doctoral students’ academic career decisions, which is consistent with the existing findings. Career choices are not only influenced by HWB factors (e.g., emotions and life satisfaction) [14] but also by EWB factors (e.g., personal growth and self-actualization) [64, 65]. We offer a comprehensive analysis of the effects of both HWB and EWB on individuals’ career decision-making, which differs from most previous research that has typically focused on either HWB or EWB alone.

This study examines the distinct roles of HWB and EWB in academic career choices. While HWB helps doctoral students maintain positive emotions and sound cognitive judgment in academic activities, EWB provides them with deep spiritual strength drawn from their academic pursuits. It also explores the different academic career choice strategies adopted by doctoral students in varying states of HWB and EWB. Regarding academic career choices, the belief in the value of the academic profession, which is more closely related to EWB than HWB, is a more decisive factor in whether doctoral students choose an academic career.

Previous studies have analyzed the mediating effect of well-being between self-efficacy and vocational identity development, which facilitates career exploration and career decidedness [66]. Our study also finds that self-efficacy enhances HWB, thereby influencing doctoral students’ academic career choices. Moreover, eudaimonic PWB has been linked to career indecision [67]. This study finds similar results, particularly when HWB is low and EWB is high, as doctoral students experience greater indecision and struggle with career decision-making. This study emphasizes that the well-being experiences during doctoral studies significantly affect future career choices, consistent with findings that highlight the influence of first-hand experiences gained during doctoral training [68]. Therefore, the well-being experiences associated with academic activities deserve greater attention within the context of doctoral programs.

This study reveals that the interplay between doctoral students’ well-being and their academic career choice is influenced by the unique academic environment and sociocultural context in China. The influence of managerialism, the tenure-track system, and publication requirements, such as “Publish SCI papers or no degree,” creates a highly competitive and pressure-filled environment for both supervisors and doctoral students [40, 69, 70]. This anxiety-inducing environment has been found to negatively affect doctoral students’ well-being and decrease their likelihood of pursuing academic careers. Within the context of “Shimen” (academic family), where the supervisor assumes the role of a patriarchal leader and the students act as “academic children,” bound by mutual support, loyalty, and the shared goal of maintaining “family honor” [71], traditional cultural values of respecting authority and elders may further reinforce the authority of supervisors [72]. While the “Shimen” structure provides significant support, it also imposes considerable pressure, resulting in a complex and dual-sided impact on doctoral students’ well-being and their decisions regarding academic career paths.

7. Conclusion

This study extends the understanding of well-being by examining its dual dimensions, HWB and EWB, in shaping doctoral students’ academic career choices. It highlights the interplay between these dimensions, offering a nuanced perspective on how they influence career decision-making. The findings confirm that well-being significantly influences career choice strategies. Doctoral students with high levels of both HWB and EWB demonstrate a stronger commitment to pursuing academic careers. Those with high HWB but low EWB often approach academia as a pragmatic choice, whereas students with low HWB but high EWB may face indecision and ambiguity in their career direction. When both HWB and EWB are low, doctoral students are more likely to actively opt out of academia careers.

This study offers practical recommendations for enhancing doctoral students’ well-being and fostering an academic culture that supports personal and professional growth, thereby contributing to the development of a supportive and high-quality doctoral education system. Institutions can reduce reliance on overly competitive metrics in evaluating doctoral students and promote more collaborative research projects, thereby strengthening their sense of belonging and teamwork skills. Professional psychological counseling services should be provided to help doctoral students cope with stress, anxiety, and emotional challenges, improving their well-being. Given the importance of EWB, institutions can organize courses, workshops, or mentorship programs to help doctoral students recognize the value of their research, thereby enhancing their intrinsic motivation and sense of meaning. Moreover, institutions should emphasize balanced authority in student–supervisor relationships and open communication to avoid potential authoritative suppression. Encouraging mutual support and collaboration between supervisors and students can foster a more inclusive and constructive academic environment.

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations must be acknowledged to contextualize the findings and guide future research. The purposive sampling included 37 participants who viewed academia as a potential career, limiting the representativeness of the sample by excluding perspectives from those considering nonacademic career paths. Including doctoral students with diverse career intentions—such as aspirations in industry or government—could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing career decisions. A comparative analysis between students committed to academia and those pursuing alternative paths would provide richer insights into the relationship between well-being and career choices. Furthermore, the study’s focus on students within the Chinese academic system and its unique sociocultural dynamics may limit the generalizability of the findings to other cultural or institutional contexts. Cross-cultural comparisons could provide broader insights into how well-being and career choices are influenced by diverse academic and sociocultural environments. Finally, while the qualitative approach employed in this study offers depth and contextual richness, it limits generalizability and may not fully account for broader patterns or causal relationships. Future research could adopt a mixed-methods approach, integrating qualitative insights with quantitative data to validate findings and identify trends across larger populations. Addressing these limitations underscores the need for further research to achieve a more inclusive and holistic understanding of the factors shaping doctoral students’ well-being and career trajectories.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; methodology, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; software, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; validation, Huirui Zhang and Xiaoxiao Li; formal analysis, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; investigation, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; resources, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; data curation, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; writing – original draft preparation, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; writing – review and editing, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; visualization, Huirui Zhang, Lingyu Liu, and Xiaoxiao Li; supervision, Xiaoxiao Li; project administration, Lingyu Liu; funding acquisition, Huirui Zhang and Lingyu Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Found Education Youth Project, grant number CIA230320.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.