Enhancing Personal Protection in Dealing With Nurses’ Alarm Fatigue: A Prescriptive Model

Abstract

Introduction: Psychological stress from managing frequent alarms contributes to fatigue among nurses in intensive care units (ICUs), a condition known as “alarm fatigue.” Neglecting and inappropriately managing alarm fatigue can cause irreversible consequences for nurses and patients.

Objective: To understand how to improve nurses’ contextual exposure to alarm fatigue and its consequences.

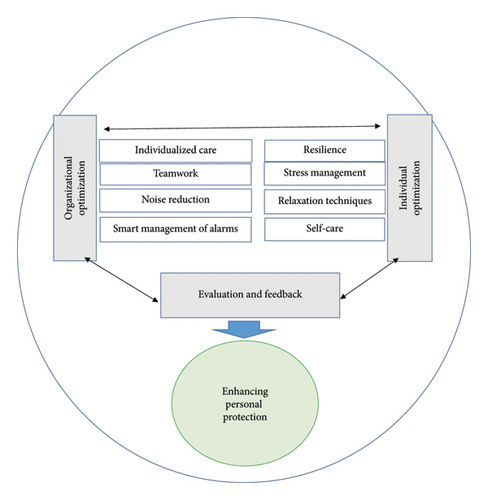

Method and Results: Using existing theories and concepts based on the Walker and Avant method for theory synthesis, a descriptive theory of “trying to create a holistic balance” for improving nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue was developed. The main and central concept of this prescriptive model was “enhancing the personal protection” of nurses. Improving personal protection to optimize nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue was carried out through individual optimization, organizational optimization, and evaluation and feedback.

Conclusion: Nurses and nurse managers are responsible for providing an optimal individual platform and an optimal organizational platform to help remove contextual obstacles intensifying nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue in ICUs. Efficient strategies for personal protection help manage and moderate alarm fatigue among nurses, so that a comprehensive, effective, scientific, and ethical balance in ICUs can be achieved.

1. Introduction

In intensive care units (ICUs) where patients with critical conditions are admitted, the sound of alarms is pervasive. Nurses working in ICUs are exposed to hundreds of alarms during their work shifts, as they monitor patients’ conditions 24 h a day [1]. The increasing number of clinical alarms related to medical equipment has become a big concern in hospitals [2]. The excessive number of false alarms leads to sensory overload and reduces nurses’ sensitivity to alarms. Therefore, staff are reluctant to respond to real threats due to what is called alarm fatigue [3].

Noisy alarms can lead to stress symptoms among nurses including fatigue, concentration problems, and nervous tension [4]. Encountering frequent alarms and the noise caused by alarms causes mental, sensory, and physical overload in nurses, creating a stressful, confusing, and tiring work environment in ICUs. This concept is divided into two dimensions: “psychological imbalance” characterized by high sensitivity to alarms, nervousness, occurrence of mental stress, anxiety and concern, sensory overload, feeling of mental fatigue, feeling of tiredness, and impaired concentration and “physical imbalance” characterized by hearing irritation and the occurrence of sleep disorders and headaches [5].

It has been shown that frequent false alarms can reduce nurses’ trust in clinical alarms and lead to inappropriate deactivation of alarms by nurses [6]. When critical alarms are neglected, the chance of patient harm is enhanced [7]. Disabling and turning off alarms and changing the range of alarms to reduce the number of alarms are the most common reactions to alarm fatigue. These passive behaviors can lead to the loss of vital alarms and patient harm [8]. Besides its complications and risks for patients, it makes nurses secondary victims as they may have the feeling of guilt and leave their job [9]. Unnecessary alarms are also associated with staff dissatisfaction, reduction of staff health, turnover intention, frequent interference in patient care processes, medical errors, acute cognitive overload, staff desensitization, noise pollution and disturbance to patients, disturbance in the sleep circadian rhythm, patients’ and families’ dissatisfaction, practice errors, and legal issues [10].

As healthcare environments continue to become more dependent on technological monitoring devices used for patient care, it is crucial to inform nurses about the consequences of alarm fatigue. They should be educated on how to prevent it from negatively impacting their performance and understand its potential consequences for patient safety [11]. In addressing alarm fatigue, strategies to reduce the number of nonactionable alarms have been suggested. Individual and organizational approaches, often focusing on alarm devices and modifying technology and the environment, have been identified. Smart alarms, which consider multiple parameters, rate of change, and signal quality, can reduce the number of false alarms. Hospitals should form an interdisciplinary alarm management committee to conduct alarm risk assessments, provide strategies to reduce alarms, and establish protocols for setting and responding to alarms [12]. There appears to be a “blind spot” regarding practical recommendations to influence healthcare providers’ behavioral factors regarding clinical alarms [10]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis study, it was found that the proposed interventions did not have a significant effect on reducing alarm fatigue [13]. Alarm fatigue can affect nurses’ efficiency, and interventions to reduce alarm fatigue and develop appropriate guidelines are necessary [14]. Nurses are the main users of clinical alarms; however, researchers have largely overlooked the fatigue aspect of alarm fatigue, such as stress, anxiety, and worry, and have focused on alarm management and organizational strategies. Therefore, there is a need to provide a comprehensive model regarding alarm fatigue management.

The theory of “trying to create a holistic balance” in facing with alarm fatigue in ICUs [5] can provide a suitable basis for designing and prescribing strategies regarding nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue. In this theory, the perceived concern of nurses is a “threat to personal balance.” The strategies employed by nurses often fail to fully address these concerns and may not effectively mitigate the adverse consequences for nurses, patients, and the organization. The final goal of this prescriptive theory is to “enhance personal protection” as to enable nurses to respond to existing perceived concerns which is a “threat to personal balance.” Applying personal protection in facing with alarm fatigue, the ability to adjust to unsafe and inappropriate environments, and overcoming burnout, patient victimization, and damage to the organization are expected. In the study, the researchers aimed to answer the following research question: “How can nurses’ contextual exposure to alarm fatigue and its consequences be improved?”

2. Methods

The theory–research–theory approach by Meleis [15] was used to design a prescriptive model, employing grounded theory as the framework according to the method suggested by Walker and Avant [16].

Meleis classifies nursing theories into two types based on their goals: descriptive and prescriptive. Descriptive theories aim to describe phenomena, speculate on how they occur, and outline their consequences. In contrast, prescriptive theories focus on nursing interventions and their outcomes. In the theory–research–theory approach, theory informs the development of research questions, and the results that address these questions contribute to applied theory. This approach uses theory as a framework for defining variables and propositions, guiding mental, interpretive, and problem-solving processes to describe findings.

The theory–research–theory method involves four key steps: selecting a theory compatible with the field of nursing to explain the phenomenon of interest; redefining and operationalizing the theory’s concepts for research purposes; synthesizing the findings to modify or develop the original theory; and in some cases, this process may lead to the creation of a new theory [15]. A nursing prescriptive theory includes propositions that seek to bring about change and predict the consequences of a particular strategy in an intervention. In the theory synthesis method, data based on observations are used to build a new theory. The synthesis approach allows the theorist to combine isolated components and elements of information that are not yet theoretically related. This approach is suitable where the researcher or theoretician collects data or tries to interpret them without a clear and assumed theoretical framework and includes any integration, communication, and judgment. Based on the results obtained from the grounded theory [5] and the application of the Walker–Avant approach [16], the synthesis of the prescriptive model was carried out. The three basic stages of designing the model based on Walker and Avant’s synthesis approach in relation to the findings have been described as follows.

2.1. Identifying Main Concepts as a Basis for Theory Building

The grounded theory and its central concept as “trying to create a holistic balance” have been described somewhere else [5]. “Trying to create a holistic balance” refers to the strategies that nurses use to manage alarm fatigue. This includes calming themselves through smart care practices, making nonstandard adjustments to alarm devices, and implementing clinical measures such as the excessive use of sedation drugs in patients. These strategies encompass both proactive and passive approaches, aimed at restoring balance to the chaotic environment created by the frequent occurrence of alarms. It covered the adverse consequences of nurse burnout, victimization of the patient, and harm to the organization, as well as some strategies used by the participants such as deliberate balancing, conditional prioritization, and negligent performance. They were unable to remove the threat to personal balance in nurses in facing with alarm fatigue, leading to adverse consequences. Therefore, “enhancing personal protection” was adapted and determined as the central concept and as support for improving strategies and processing the prescriptive model. Enhancing personal protection involves addressing and eliminating threats to personal balance across all dimensions—sensory, mental, and physical—that nurses face due to alarm fatigue. Also, the concepts of “person,” “nursing,” “health,” and “environment” (Table 1) were determined as the conceptual framework of the model design along with the concept of “enhancing personal protection” of nurses in facing with alarm fatigue in ICUs.

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Person | Nurses working in ICUs, as the primary users of clinical alarms, are most affected by alarm fatigue. However, other healthcare organization members, including supervisors, hospital managers at various levels, ICU doctors, and medical equipment engineers, also play a crucial role in enhancing the personal protection of nurses against alarm fatigue. Their collective efforts can contribute to mitigating the impact of alarm fatigue and improving the overall work environment in the ICU. |

| Nursing | Enhancing the personal protection of nurses to mitigate alarm fatigue involves both individual and organizational optimization, achieved through collaborative efforts between nurses and nursing managers. This process includes building resilience, managing stress, and promoting self-care. It also involves developing personalized care strategies and fostering effective teamwork. Reducing noise pollution in the department and implementing intelligent alarm management are key components, with a focus on preventing burnout and improving patient safety. |

| Health | Nurses’ self-efficacy in managing mental and physical challenges caused by alarm fatigue involves having the skills to effectively address and combat this issue in clinical settings and through both individual and team actions. By enhancing their self-efficacy, nurses can better manage the consequences of alarm fatigue, such as burnout, patient harm, and organizational impact, ultimately leading to improved outcomes and safer patient care. |

| Environment | In ICUs, the environment influencing alarm fatigue encompasses both internal and external factors. The internal environment includes the sensory, psychological, and emotional perceptions of nurses. The external environment consists of organizational elements, such as other ICU staff, supervisors, doctors, hospital managers at various levels, and patients. It also includes the physical aspects of the department, such as sound sources and alarm equipment. |

- Abbreviation: ICU = intensive care unit.

2.2. Reviewing or Referring to the Literature to Determine Factors Related to Main Concepts and to Determine Their Interconnections

A review of the international literature guided by the central concept was conducted, and variables related to the central concept were noted. Certain associations were systematically recorded and, where possible, marked about whether there was evidence supporting a one-sided, two-sided, neutral, negative, positive or unknown, weak, strong, or ambiguous effect. These interconnections were made during a comprehensive and detailed review of current review studies and a thorough literature review. Identifying connections was performed via sources related to propositions and concepts in addition to written sources. For example, the researcher’s quantitative and qualitative observations were translated into communication statements and then were used in the theory building process like any other statement [16].

To determine factors related to the concept of “enhancing personal protection” and identify central connections, the researchers searched and analyzed authentic texts to find data, complete and repair existing weaknesses, and examine proposed strategies for enhancing personal protection. All studies in the last 20 years (2002–2022) were searched on the databases of PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest, Springer, ScienceDirect, Wiley, and Google Scholar. Also, electronic journals publishing relevant studies were examined using keywords related to the central concept derived from the findings of the grounded theory [5]. In reviewing the literature, the researchers were looking for an answer to the question, “How can nurses improve the threat to personal balance caused by encountering alarm fatigue with the help of enhancing personal protection?” In the literature review, the basis of the selection of studies was to achieve concepts and strategies to correct and improve the unfavorable consequences of the underlying theory. A combination of the following keywords and their synonyms in English was used for the search process: self-care, relaxation techniques, tension management models, stress management models, smart/intelligent care models, noise reduction models, personalized/individualized healthcare models, teamwork models, burnout prevention models, and patient safety promotion models. For a more sensitive search, logical operators “AND,” “OR,” and “NOT” were used.

The research synthesis was done independently by two researchers. Retrieved studies were carefully examined, and existing strategies, concepts, and models related to the study’s central concept were explored. The search led to 954 articles, of which 225 studies remained after removing duplicates. They were screened and 20 articles published in English were appraised, and 8 studies were excluded (Table 2). The researchers reviewed the articles to understand how nurses reduced the threat to personal balance caused by alarm fatigue with the help of enhancing personal protection. Accordingly, strategies and factors related to the concept of “enhancing personal protection” were explored.

| First author (year) | Method | Title | Concepts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Back et al. (2016) [17] | Model design | Building resilience for palliative care clinicians | Resilience building skills. |

| Yılmaz (2017) [18] | Review | Resilience as a strategy for struggling against challenges related to the nursing profession | Interventions to improve nurses’ resilience in three areas: personal characteristics, workplace characteristics, and social networks. |

| Allison (2007) [19] | Model design | Self-care requirements for activity and rest: an Orem nursing focus | Strategies to reduce stress and achieve rest and relaxation in four categories. Inactivity: acupuncture, aromatherapy and sound therapy, autogenic exercise, progressive muscle relaxation, biofeedback; light activities: bathing, hobbies, massage; moderate activity: entertainment, playing a musical instrument, sports and yoga; extreme activity: camping, walking, running, sports (competition, team). |

| Edwards and Burnard (2003) [20] | Systematic review | A systematic review of stress and stress management interventions for mental health nurses | Interventions for stress management: behavioral therapy training with the aim of improving nurses’ preparation to perform therapeutic duties; individual relaxation techniques for stress management; stress management training workshops; programs based on social support for nurses. |

| Manzoni et al. (2008) [21] | Systematic review | Relaxation training for anxiety: a 10-year systematic review with meta-analysis | The effect of Jacobson’s progressive relaxation methods, autogenic exercises, applied relaxation, and meditation on anxiety problems |

| Lusk and Fater (2013) [22] | Concept analysis | A concept analysis of patient-centered care | The concept of patient-centered care characterized by power, autonomy, joint decision-making, and the importance of individualizing patient care. Implications of this concept by improved patient satisfaction, health care quality, and perceived health outcomes. |

| Kalisch et al. (2009) [23] | Grounded theory | What does nursing teamwork look like? A qualitative study. | Teamwork has five central elements, including team leadership, collective orientation, mutual performance monitoring, supportive behavior, and compatibility. |

| Stevens et al. (2012) [24] | Model design and testing | Smart alarms: multivariate medical alarm integration for post CABG surgery patients | The concept of “smart alarms” using advanced technologies of smart alarms and integrating the information obtained from various monitoring parameters to reduce the number of false alarms. |

2.3. Organizing All Concepts and Statements of Communication and Existence Within a Related Whole and Presenting the Phenomenon in an Integrated and Efficient Manner

A list of propositions related to the central concept of the study was provided and was organized in terms of the general pattern of their interconnections in an explanatory form and by using a diagram to depict interrelationships between them comprehensively and holistically [16].

The central concept of this model is to enhance personal protection among nurses. Personal protection is a dynamic, continuous, and responsible process aimed at countering the threat to personal balance caused by alarm fatigue. This is achieved through active, deliberate, conscious, and preventive efforts to regulate emotions, feelings, and psycho-sensory-physical load. It involves both individual and organizational optimization strategies to manage the impact of alarm fatigue effectively. This protection includes self-control and control over the situation that includes problem-solving, reducing the adverse consequences of nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue, reducing nurse burnout, increasing patient safety, and protecting the organization.

Enhancement of personal protection to optimize exposure to alarm fatigue is performed through the following three steps: individual optimization, organizational optimization, and evaluation and feedback. Nurses within the individual optimization step develop effective strategies by resilience, stress management, relaxation, and self-care. In the step of organizational optimization by the development of personalized care according to the unique needs of patients, effective team collaboration, reduction of noise pollution in the department, and intelligent management of clinical alarms create an atmosphere that protects themselves and their colleagues from the threat to personal balance caused by alarm fatigue. Formative evaluation and process evaluation or final evaluation are performed with the aim of measuring the progress of the measures taken in the previous two steps and are in line with the overall goal of the prescription model to enhance the personal protection of nurses in facing with alarm fatigue.

3. Results

3.1. Strategies or Operational Steps of the “Enhancing Personal Protection” Model

Strategies were derived from the concepts of the prescriptive model and provided the special goals of the model. It showed interconnections and logical sequences of the steps of the model as a continuous process so that the goals of the model were achieved. Operational steps in this model were designed and developed based on the steps of the nursing process and in three stages. All steps of the process were necessary to reach the final goal. The operational steps of this process were a set of strategies for improving personal protection by using educational, self-protection, and management strategies (Figure 1). The steps of the present model include three stages: individual optimization, organizational optimization, and evaluation and feedback. These steps were organized into a dynamic cycle, where actions taken at each step were repeated in subsequent steps and might involve moving both forward and backward within the process. Each step was reported along with the details of actions that should be taken to empower nurses to effectively deal with alarm fatigue.

3.1.1. Individual Optimization

It aimed to empower nurses in facing with alarm fatigue through training and the use of strategies that enabled nurses to effectively deal with the threat to personal balance caused by alarm fatigue. As it was found in the descriptive theory [5], nurses faced problems in maintaining mental–emotional–physical balance when faced with alarm fatigue. They experienced anger, mental stress, anxiety and worry, sensory overload, mental fatigue, impaired concentration, and physical problems such as hearing irritation, sleep disorders, and headaches. Strategies to manage or reduce overload by nurses reduced nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue. Therefore, this step was designed to solve the main concern of nurses in facing with alarm fatigue described in the grounded theory. Strategies were building resilience, stress management, relaxation techniques, and promoting self-care. The implementation steps of each strategy were presented separately.

3.1.1.1. Building Resilience

Burnout or resilience was the result of the interaction of personal resources with work demands. It occurred when work demands exceeded personal resources. Conversely, resilience occurred when personal resources were stretched to meet work demands. Improving resilience was applicable at both the individual and organizational levels. At the individual level, resilience skills included cognitive-behavioral therapy, positive psychology, and mindfulness. These skills encompassed using personal strengths, pursuing staying active throughout the day, setting healthy external boundaries, self-regulating emotions, recognizing cognitive distortions, creating realistic expectations for one’s performance, finding meaning in daily work, and committing to long-term development. At the organizational level, the opposite of job burnout was interest in work as job involvement and strategies included the possibility of control by influencing decisions that affected work, structuring rewards such as monetary, social, or recognizing a job, creating a community to support nurses, and promoting culture where conflicts were managed openly, promoting justice in decisions that affected the nurse’s work, recognizing the values that inspired nurses from the priorities of the system, and adjusting the workload in such a way that the work requirements did not exceed the limits of any human being [17].

3.1.1.2. Stress Management

Occupational stress was a major health problem for individuals and organizations, leading to burnout, illness, staff turnover, and reduced work performance and quality. Stress management as a general term encompassed a wide range of different methods designed to reduce stress and improve coping abilities. Interventions changed the environment to reduce the potential for stress and helped people modify their appraisal of stress or cope more effectively with stressors [20].

Behavioral therapy training aimed to enhance nurses’ readiness for therapeutic tasks by helping them develop skills and knowledge to manage occupational stress more effectively. This involved conducting stress management training workshops designed to reduce job burnout among nurses. These workshops educated participants in individual relaxation techniques such as Jacobson’s progressive muscle relaxation, clinically standardized meditation, biofeedback, and autogenic training.

3.1.1.3. Use of Relaxation Techniques

Anxiety arises from a variety of factors, including biological, psychological, and social. Clinical studies have shown limited evidence about the effectiveness of antianxiety medications in the long term. For this reason, relaxation techniques were one of the most widely used approaches in anxiety management, either alone or in a larger treatment package. The longer the relaxation protocol, the greater its effect on reducing anxiety. It would be much more effective if the relaxation technique was repeated at home [21]. Studies showed that the continuous use of a single technique was more effective than combining multiple techniques. Therefore, after educating nurses about the four introduced techniques, they were instructed to choose one and consistently apply it.

3.1.1.4. Promoting Self-Care

The two basic conditions for fulfilling the need for self-care included maintaining the level of physical activity in accordance with abilities and a sufficient amount of rest and relaxation to maintain the required and desired level of activity, in order to achieve a balance between activity and rest [19].

So-called inactivity methods were acupuncture, aromatherapy/sound therapy, autogenic exercise, progressive muscle relaxation, and biofeedback; breathing exercises such as deep abdominal breathing; and rhythm, hypnosis, thought control, meditation, prayer, sensory walking, lying down, and short breaks during the day. Light activities were bathing; paying attention to one’s favorite hobbies; massage as manipulation of pressure points, touch therapy, and reflexology; playing one’s favorite games; and sitting techniques such as reading, listening to music, watching movies, television, and theater, and studying to develop knowledge, skills, and competence in areas of interest.

Moderate activities as hobbies were gardening, woodworking, traveling, maintenance, pet training, and playing a musical instrument; physical exercise as walking, swimming, golf, and shopping; and social participation/interaction as participation in special interest groups, support groups, or community volunteer work, spiritual or religious practices, participation in service activities, helping others, and yoga.

Intense activities were camping, walking, running, and competitive sports that were taught to nurses through training workshops.

3.1.2. Organizational Optimization

In the second step of the process of enhancing personal protection, strategies and steps were introduced that needed to be used collectively to make these steps effective, and all members of the ICU participated in these strategies. To achieve goals, trainings were also performed in groups, and efforts were made to attract the cooperation of all members of the ICU team. Also, achieving goals required the cooperation and support of hospital managers. The focus was more on environmental and structural reforms and improving the use of equipment. Strategies and steps used in this stage included the development of individualized care, teamwork, noise reduction, and smart management of alarms.

3.1.2.1. Development of Individualized Care Provided by Nurses

The individualization of care uniquely for each patient reduced exposure to repetitive and nonactionable alarms and increased the quality of nursing care. Setting the alarm range of devices to the appropriate range according to the clinical condition of the patients was considered.

Through the formulation and communication of instructions, protocols and policies related to the individualization of alarm device settings by the hospital management were established. The training of individualization of alarm device settings according to the patient’s physiological condition to reduce false and useless alarms was implemented via workshops.

3.1.2.2. Teamwork

Effective teamwork reduced turnover intention, improved performance, increased the quality of care, reduced errors and reduced stress in nurses, and increased patient satisfaction. Training workshops were conducted to promote effective teamwork among ICU nurses based on the model of Kalisch et al. [23]. These workshops focused on enhancing leadership techniques for supervisors to better manage the ICU team structure, ensuring fair distribution of workload among team members, and providing support from both leaders and fellow team members. They also aimed to improve staff attitudes toward teamwork by teaching the core elements of effective teamwork, including collective orientation (fostering cohesion and prioritizing team success over individual needs), mutual performance monitoring (observing and understanding team roles), supportive behavior (assisting each other in task performance), and adaptability (adjusting strategies and resource allocation based on environmental information).

3.1.2.3. Noise Reduction

Increased exposure of nurses to alarm fatigue in ICUs was largely due to high noise pollution. Reducing noise levels helped mitigate the threat to personal balance. Personnel training programs were established to address this issue by introducing the sources of noise and emphasizing the importance of noise reduction. These programs included behavior modification strategies, such as discussions on noise pollution and its impact on both patients and the work environment. They also involved identifying noise sources through observation and interviews. To manage noise, several measures were implemented: using low light during night shifts to encourage quieter communication, limiting pager use, lowering staff speaking tones, and adjusting alarm volumes to safe levels. Additionally, alarms related to equipment malfunctions were repaired by the hospital’s medical equipment engineers, phone ringing volumes were reduced, and silence signs were used in the ward. Efforts were also made to repair trolley wheels to minimize noise, control background sounds, and regulate department traffic to prevent unnecessary crowding.

3.1.2.4. Smart Management of Alarms

As stated in the descriptive theory [5], the first strategy used by nurses in facing with alarm fatigue was the use of smart care. Efforts were made to teach nurses about the methods of smart management of clinical alarms with the aim of reducing the number of false and useless alarms.

Development of a smart alarm algorithm in the ICU was an algorithm by which several hemodynamic parameters and vital signs were integrated, and if all the parameters confirmed the existence of a critical situation, the alarm of the monitoring system was activated [24]. To address alarm fatigue, several measures were applied: using alarm technology with short delays to reduce nonactionable or ineffective alarms caused by patient movement, implementing daily replacement of electrocardiographic monitoring electrodes, ensuring proper skin preparation, and adhering to the American Heart Association guidelines to prevent overuse of continuous cardiac monitoring [25]. Additionally, efforts were made to resolve alarms related to device malfunctions.

3.1.3. Evaluation and Feedback

Evaluation was performed in two ways: formative and process or final. Formative evaluation was performed as a team consisting of nurse managers who supervised the implementation of the functional steps and processes of each of the steps of the model and determined to what extent the performance of the nurses was in accordance with them. Also, it was to what extent nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue decreased. The evaluators were well acquainted with their tasks and evaluation goals to provide methods and tools for evaluation before implementing the model.

The results of continuous evaluations helped with adjusting problems and removing problems and obstacles. At the end of the pilot period of the implementation of the prescriptive model, it was necessary to evaluate the success rate of the implementation of the personal protection enhancement model, i.e., empowering nurses to effectively manage alarm fatigue, with specific and appropriate tools such as checklists or questionnaires.

To measure the level of exposure of nurses to alarm fatigue before, during, and after the implementation of the personal protection enhancement model, the questionnaire of nurses’ alarm fatigue provided by Torabizadeh et al. [26] was used. Finally, after collecting data from the final evaluation and data analysis, the consequences of the implementation of the prescriptive model were properly reflected to the nurses and nursing managers for motivating nurses and managers, existing obstacles and problems were taken into consideration, and suitable measures were taken to remove them.

3.2. Prescriptive Model Statement for Enhancing Personal Protection in Facing With Alarm Fatigue

Nurses utilized an optimal individual platform to address personal challenges related to alarm fatigue, while managers established an optimal organizational platform to eliminate contextual obstacles and structural issues that exacerbated the problem. This combined approach aimed to reduce the impact of alarm fatigue by addressing both individual and infrastructural factors. Strategies including building resilience, stress management, use of relaxation techniques, promoting self-care, personalized care, teamwork, noise reduction in the department, and smart management of alarms in planning and moderating alarm fatigue led to a comprehensive, effective, and scientific balance in response to alarms. Evaluation and feedback measured the progress made in line with the general goal of the prescriptive model to enhance nurses’ personal protection in facing with alarm fatigue. Burnout of nurses as a result of facing alarm fatigue and the damages caused by this fatigue on patients as secondary victims and the organization were reduced, leading to achieving the ultimate goal of the healthcare organization as the provision of safe and high-quality care.

4. Discussion

The prescriptive model developed in this study represents the first model designed to manage nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue. This model focuses on enhancing personal protection for nurses dealing with alarm fatigue in ICUs and is grounded in a theory derived from interviews with ICU nurses [5]. Nurses faced the threat to personal balance due to alarm fatigue and tried to create a holistic balance. It occurs due to disturbing factors in the workplace, in the improper circuit of individual roles, and in the context of distorted organizational structure and unsafe infrastructure. The ineffectiveness of the used strategies and frequent exposure to frequent alarms in the ICUs caused nurses’ burnout, harm to the patient, and negative consequences for the organization [5]. The most important and effective strategy used by nurses should focus on resolving concerns raised in facing with alarm fatigue, i.e., the threat to personal balance, which was named “enhancing personal protection.” The prescriptive model for enhancing the personal protection of nurses in facing with alarm fatigue was designed in three main steps, namely, individual optimization, organizational optimization, and evaluation and feedback to further increase the effectiveness of strategies to deal with alarm fatigue. In this prescriptive model, the metaparadigmatic elements of person, health, nursing, and environment have been defined specifically and in accordance with the model’s aim. The presence of two-way arrows between three operational steps in this model indicates the continuous and mutual relationship of these steps and shows that evaluation is not the end point of this process. Previous studies have provided individual and organizational strategies to deal with alarm fatigue among nurses based on the review of existing texts and protocols.

Stressors such as work overload, role conflict, lack of time, and lack of self-care can lead to stressful and traumatic situations for nurses. These situations can lead to physical and mental problems such as fatigue, irritability, decreased concentration, feelings of depression, and emotional exhaustion. Despite these challenges, resilience enables nurses to cope with their work environment and maintain healthy and stable psychological functioning [18]. Nurses can be empowered to manage alarm fatigue through resilience promotion strategies. At the individual level, this includes mindfulness, adaptability, professional competence, self-efficacy, and maintaining life balance through exercise, rest, and personal interests. At the organizational level, effective workload management, encouragement and improvement of job satisfaction, and the creation of support groups contribute to enhancing nurses’ ability to cope with alarm fatigue. Coping strategies for stress management include social support, having stable relationships, recognizing limitations, dealing with problems immediately, being fit, living well at home with family and life partner, and interests outside of work. The first step in managing stress is to prevent problems in the workplace in the first place by eliminating or minimizing stressors. The next step is to minimize the negative effects of stress through training and management strategies, and the last step is to help those who experience the effects of stress [20]. Teaching relaxation techniques to overcome nurses’ anxiety seems to be useful and necessary as one of the features of their main concern in facing alarm fatigue because relaxation techniques are one of the approaches that have been used in anxiety management, alone or in a larger treatment group, and have had favorable results. Therefore, these strategies can be used to reduce nurses’ anxiety as one of the dimensions of alarm fatigue.

Cvach [12] in an integrative review classified strategies to reduce alarm fatigue into strategies related to technology, hospitals, and healthcare providers. Technology-related strategies included smart alarms, alarm technology that has short delays, and standardization of alarm sounds. Hospital-related strategies were the establishment of an interdisciplinary alarm management committee to conduct an alarm risk assessment and consider strategies to reduce alarms. Protocols for setting alarms and responding to alarms should also be devised. Alarm enhancement technology provides an additional means of delivering alarm signals from monitors to employees. It can include pagers, telephones, and auxiliary displays such as waveform displays. Noise reduction strategies should be used to reduce patient and staff stress symptoms. Strategies related to healthcare workers should be used so that staff can prevent false alarms by turning off alarms for a short period of time before handling and moving the patient. Setting alarms based on patients’ actual needs ensures that alarms are valid. Proper skin preparation and daily replacement of chest electrocardiography reduce false alarms [12]. Although the presented strategies focused on alarm devices and modification of technology and environment, the present prescriptive model had a more comprehensive view on the process of prevention and management of alarm fatigue. In the case of enhancing personal protection, the focus is on improving nurses’ abilities to deal effectively with alarm fatigue. Also, in the prescriptive model, the consequences of nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue are reduced through strategies to prevent nurses’ burnout such as resilience, stress management, and relaxation.

Turmell et al. [25] presented evidence-based alarm management strategies which were derived from the recommendations by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). They were daily replacement of electrodes with appropriate skin preparation, elimination of nonactionable and repetitive alarms, and appropriate setting of the default range of equipment alarms. Also, nurses’ training and instructions were encouraged to individualize alarm ranges and reduce the overuse of continuous cardiac monitoring by implementing the American Heart Association’s guidelines. These strategies resulted in an overall reduction of alarms by 18.5% [25]. Although the strategies considered in this study aimed at reducing the number of unnecessary alarms, in the operational steps of the current prescriptive model, the strategies were considered and used under the smart management of alarms.

Smart care in alarm management can be performed through identifying the cause of alarm and taking timely actions, individualizing alarm settings, reducing the number of nonactionable alarms, effective teamwork, improving the physical environment and ward arrangement, and self-calmness [27]. Bi et al. [28], by holding a monitor alarm management course based on the theory of planned behavior with a one-way blind randomized trial approach, significantly reduced the total number of alarms, the number of nonuseful alarms, and the alarm fatigue score [28]. In this study, researchers focused on the reconstruction of nurses’ awareness and behavior regarding alarm management. However, in the presented prescriptive model, an all-round approach was tried to provide a proper management of alarm fatigue by nurses. In addition to proper alarm management strategies to reduce the number of alarms, empowering nurses to protect themselves in the tiring environment caused by frequent alarms was considered through different strategies such as stress and anxiety management and self-calming, as well as organizational support such as optimizing equipment and environment, and promoting effective team cooperation.

In developing this prescriptive model, negative and confusing dimensions from the descriptive model [5] were removed. This refinement aimed to ensure that the model effectively achieves the desired outcomes: preventing, managing, and reducing nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue, as well as adjusting and mitigating the adverse effects of such exposure. Further qualitative studies are needed to explore concepts and elements influencing nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue in ICUs and to identify effective personal protection strategies. Many aspects of the current model require further development and refinement. Additionally, creating a tool to assess the model’s applicability in clinical practice would be beneficial for evaluating its effectiveness and ensuring its practical utility. Interventional studies as well as action research studies are valuable to evaluate the efficiency and applicability of the personal protection model.

4.1. Limitations

One of the limitations of the present study was the use of secondary sources to analyze appropriate strategies for managing alarm fatigue in nurses. The selection methods of the selected studies were not comprehensive and systematic through the specified tools, especially in the data analysis process, which means that the quality of the studies should be critically evaluated.

5. Conclusion

The model of enhancing the personal protection of nurses in facing with alarm fatigue in ICUs was derived from the development of a special grounded theory in clinical nursing. The dimensions of the descriptive model that influence nurses’ efforts to prevent or manage alarm fatigue—such as contextual factors, utilized strategies, and their consequences—were carefully considered. This approach aimed to create favorable final outcomes while adjusting and correcting any unfavorable aspects as much as possible.

The current model can serve as a foundational framework for developing additional practical models related to nurses’ exposure to alarm fatigue. Evaluation, a crucial stage in the nursing process, is necessary to assess progress in enhancing personal protection, identify the current situation, and outline the desired outcomes in relation to the implementation of this model. Formative evaluation provides an opportunity to identify any deviations from the model’s goals and to implement corrective measures to address related issues.

The use of the current model can help raise awareness among nurses and nurse managers about alarm fatigue, aligning with standard principles of patient safety and nurses’ self-protection. It can foster a supportive, motivating, and preventive clinical environment that promotes safe and high-quality patient care in ICUs. Based on this model, educational content on alarm fatigue can be developed for both nurses and nursing managers. Additionally, standard protocols and guidelines for managing clinical alarms, as well as standardizing the environment and alarm equipment in ICUs, can be established.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University (decree code: IR.MODARES.REC.1399.146).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Study design and conceptualization: Ali Movahedi, Afsaneh Sadooghiasl, Fazlollah Ahmadi; data collection: Ali Movahedi; data analysis and interpretation: Ali Movahedi, Afsaneh Sadooghiasl, Fazlollah Ahmadi, Mojtaba Vaismoradi; manuscript writing: Ali Movahedi, Afsaneh Sadooghiasl, Fazlollah Ahmadi, Mojtaba Vaismoradi; study supervision: Afsaneh Sadooghiasl, Fazlollah Ahmadi, Mojtaba Vaismoradi.

Funding

This study was supported by Tarbiat Modares University, IR.MODARES.REC.1399.146.

Acknowledgments

This article is one part of the PhD dissertation in nursing by the first author (A.M.) approved and supported by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.