Students’ Satisfaction, Confidence, and Experience With Mental Health Simulation in a Middle Eastern Nursing College: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

Aims: Students are the center of the teaching and learning process, and simulation is a skill-oriented and student-centered learning strategy. The study’s objectives were to assess the students’ satisfaction and self-confidence after learning through simulation and explore their experience of mental health nursing simulation.

Methods: The study employed an explanatory sequential mixed-methods approach, starting with a quantitative phase that used a descriptive survey to assess students’ perceived confidence and satisfaction with simulation-based learning in mental health. Data were collected from a pragmatic sample of 81 students using the Simulation Confidence and Learning Scale (SCLS). This was followed by a qualitative phase with a descriptive qualitative design, where six focus group interviews explored students’ perceptions of mental health simulation as a teaching strategy. A total of 48 students participated in the focus group interviews (eight students in each). The qualitative findings were used to explain and deepen the understanding of the quantitative results.

Results: Most of the students were female (77.8%), and aged 21 years (64.2%). Most of them (62%) perceived high satisfaction and high self-confidence (50.62%) after the simulation practice. Students’ perceived satisfaction was independent of their gender (p = 0.373) and age (p = 0.237) but was associated with their cohort or year of study ((p = 0.005), whereas students’ perceived self-confidence was independent of their gender (p = 0.190), age (p = 0.598), and year of study (p = 0.530). Five themes and 14 subthemes emerged from the thematic analysis of the qualitative data. The themes were Overall simulation experience in mental health nursing, Advantages of simulated learning, Challenges of simulated learning, Simulation vs. Actual clinical experience, and Recommended simulated cases and duration.

Conclusion: Simulated practice increased the confidence among the students for clinical practice, and students felt that supplementing actual clinical experience with simulated learning ensures equal opportunity to practice the rare clinical skills for all.

1. Introduction

Experiential learning in the laboratory is the best way to prepare students for situations they may not see or have opportunities to actively participate in during traditional clinical experiences [1]. For example, due to liability and safety concerns, students are not allowed to de-escalate agitated patients or participate in psychiatric emergency codes [2, 3]. People affected by mental health disorders are treated not only in psychiatric units but also in primary care settings, emergency departments, medical-surgical units, intensive care units, and community settings, and hence all the students need to learn these skills [4].

Nursing lecturers have found effective methods to help their students become more competent. However, since learning experiences take place through auditory, visual, kinesthetic, and other modes, nursing education has taken place in the lecture room, laboratory, and clinical setting. To increase theoretical learning, simulation, in its many forms, has been included [5].

Nursing colleges across the globe are looking for alternate ways of providing clinical training when patient care is becoming more complex and clinical placements are becoming harder to find [6]. Students’ opportunity to handle direct patient situations is being minimized due to various reasons, like changes in clinical placement policies, patient safety concerns, and ethical issues [7]. A national simulation study by the National Council of Nursing suggests simulation as an appropriate educational vehicle for the clinical training of student nurses [8].

1.1. Student Experience With Mental Health Simulation

Simulation in psychiatry for undergraduate nursing students reported to have an improvement in students’ performance, knowledge, clinical skills, empathy, teamwork work, and self-awareness[9]. Simulation offers a safe, consistent learning environment with clear goals and expectations for the student nurses. Simulation lessens the student’s performance anxiety and improves critical thinking and reasoning abilities [10]. Mental health simulation before clinical placement prepares students for basic skills, including therapeutic communication and nurse–patient relationships, mental health assessment, and essential mental health skills. Students who attended simulation before clinical placement appeared more confident in carrying out patient care activities [11].

The use of standardized patients (SPs) has enabled the student nurses to practice their interviewing skills, suicide risk assessment effectively even before being placed in the clinical. Students also reported that the theory–practice gap is been narrowed down as they were able to practice their theory lessons with the SP [12].

1.2. Student Satisfaction in Mental Health Simulation

Student satisfaction plays a key role in determining simulation effectiveness [13]. Factors like fidelity, achievement of learning objectives, simulation design, timely support and feedback from the facilitators, and teaching styles matching the learning styles of the students influenced students’ satisfaction with the simulation experience [14]. Active learning in simulation-based learning is another important factor influencing student satisfaction [15]. Use of SP over mannequins in mental health simulation was associated with high student satisfaction, particularly due to the realism, opportunities for communication, and improvement in student’s self-confidence (Luebbert) [16]. Student satisfaction with simulation is positively correlated with their self-confidence in learning [17]. Moreover, the participation of qualified instructors in training and debriefing also resulted in better learning outcomes and student satisfaction [18].

1.3. Student Confidence in Mental Health Simulation

Previous studies have shown that nursing students lack confidence in delivering mental health care due to their insufficient exposure to a variety of mental health challenges during their clinical training and lack of personal motivation to get training in this specialty due to stigma, fear, and anxiety of working with a mentally ill patient [19]. Incorporating simulation into nursing curricula can help nurse educators address these challenges in a safe environment and help them improve their performance, confidence, and satisfaction with learning [20]. Confidence and skill in aggression management and de-escalation could be improved with simulation-based education among acute care clinicians [21].

Students’ anxiety and stigma toward mental illness are actual matters of concern in Arab countries, including Oman [22]. Lack of sufficient knowledge and skill in dealing with the needs of mentally ill patients is one of the reasons for anxiety, and it would be keeping both the patient and student at risk most of the time. Eltaib et al. [23] identified that nursing students in Saudi Arabia hold positive perceptions of mental health simulation as a learning tool. Mental health simulation is recognized as an acceptable mode of teaching–learning strategy in Oman, and faculty welcomes the inclusion of simulation in the curriculum [24]. However, the student perspectives are unclear and hence, the researchers aimed to assess the student satisfaction and self-confidence attained through mental health simulation and to explore their experience of mental health nursing simulation. This would help to devise the mental health simulation learning experience more effectively and diligently in the future.

2. Methodology

- 1.

Quantitative phase:

- o

Design: Descriptive survey design

- o

Method: Students were asked to fill out a questionnaire measuring their perceived confidence and satisfaction with simulation-based learning in mental health.

- o

- 2.

Qualitative phase:

- o

Design: Descriptive qualitative design

- o

Method: Focus group interviews were conducted to explore students’ perceptions of mental health simulation as a teaching strategy.

- o

2.1. Instruments

Three instruments were used to collect the data. The first one is a students’ background pro forma that included items such as gender, age, cohort, existing experience with simulation, and opinion on simulation in mental health nursing learning experience.

The Simulation Confidence and Learning Scale (SCLS) is a 13-item tool that evaluates students’ satisfaction with simulation activity and their self-confidence in learning. It uses a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The first five items assess student satisfaction with the simulation activity, while the remaining eight items measure their self-confidence in learning. The reliability of the SCLS was confirmed through Cronbach’s alpha, with a score of 0.94 for satisfaction and 0.87 for self-confidence [25, 26].

The interview guide on Mental Health Clinical Learning Strategies was used for the focus group, which contained five open-ended items on the experience of learning mental health nursing through simulation, perceived advantages and disadvantages of simulation, suggestions for the percentage of expected simulation in mental health practical, and suggested topics for simulation. The tool was constructed by the researchers and validated among five experts from the field of psychiatric mental health nursing and got a validity index of 1.

2.2. Sample

2.2.1. Quantitative Phase

Since the objective was specific to students participating in the mental health simulation, a pragmatic and purposive sample of all students registered for the Mental Health Nursing clinical course in two consecutive semesters who were willing to participate in the study was included [27]. Thus, a total of 81 students (27 students in the first semester and 54 in the next semester) participated in the first phase. The students from two semesters were included to have the maximum number of participants with the same specified level of exposure. Mental health simulation was incorporated in both semesters, and students were placed in the Nursing Laboratory and Simulation Unit (NLSU) for 3 weeks (4.5 h × 2 days × 3 weeks = 27 h out of a total of 135 h). In contrast, the rest of their placements were in clinical settings (psychiatric units). All the students went through a similar experience both in the simulation and clinical in both semesters, based on their course objectives.

2.2.2. Qualitative Phase

A purposive sampling of students who were willing to take part in a 20-min focus group discussion after completion of their mental health simulation lab postings was included in the second phase. The data saturation was obtained at the sixth focus group discussion; thus, 48 students (8 students in each focus group interview) participated in the second phase.

2.2.3. Setting

The study was conducted in the NLSU of the College of Nursing at Sultan Qaboos University, one of the largest public universities in Oman. The NLSU has multiple labs that mimic hospital units, equipped with advanced technology recording systems and high-fidelity mannequins, which facilitate nursing regulation students’ lab training and simulation regularly.

2.2.4. Mental Health Simulation

This study utilized a structured, high-fidelity simulation-based learning experience designed to closely mimic the clinical environment of a psychiatric hospital managing complex mental health conditions. Prior to the simulation, students participated in a prebriefing session where essential knowledge relevant to the scenarios was reviewed through Microsoft PowerPoint presentations and instructional videos. These sessions also included orientation to the simulation laboratory and equipment setup.

The SP employed in the scenarios was a qualified graduate nurse who had been extensively trained using a detailed scenario script, which outlined patient history, specific physical findings, and prescribed communication behaviors. To enhance the realism of the psychiatric ward setting, the SP was supported by a virtual electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) monitoring system, which displayed dynamic vital signs and electrocardiogram (ECG) readings throughout the simulation.

Within this simulated psychiatric ward environment, nursing students engaged in practicing psychiatric assessments, therapeutic communication, and crisis intervention strategies in a controlled, safe setting. The mental health simulation scenarios included care of patients undergoing ECT, and the management of individuals with aggression, panic anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) with suicide risk. Participation in these scenarios allowed students to refine their clinical judgment, critical thinking, patient safety practices, and therapeutic communication skills, thereby strengthening overall clinical competence.

Each simulation session lasted approximately 15–20 min and was recorded for educational review. Following the simulation, a debriefing session of 30–40 min was conducted, focusing on students’ reflections concerning clinical reasoning, judgment, critical thinking, and communication skills. Simulation activities were facilitated by course faculty members who held master degrees in mental health nursing, each with over a decade of academic teaching experience. Furthermore, all faculty received training in high-fidelity simulation techniques.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Quantitative Phase

A bachelor’s in nursing science (BSN)–qualified research assistant (RA) was employed to collect the data to avoid bias in data collection. Data was collected from September 2019 to May 2020 through self-reported questionnaires at the end of each mental health simulation rotation. The students in small groups of 8 to 10 students were exposed to a set of mental health simulation experiences of selected rare mental health scenarios (such as aggression management, ECT care, etc., as listed before) for three consecutive weeks. Thus, all the students were getting equal opportunity to take part in the simulation that was spread throughout the semester. The RA met each of these student groups in the NLSU at the end of their mental health simulation rotation and explained the nature and purpose of the study. The RA distributed the questionnaires to all the participants who agreed to participate in the study and signed the informed consent.

2.3.2. Qualitative Phase

The primary researcher trained the same RA on how to conduct the focus group interview with one group using the interview guide in the pilot study, and this information was not included in the study to maintain objectivity. The RA set appointments with the consenting members who agreed to participate in the focus group interviews. Thus, six focus group interviews were held that lasted for about 20 min each, and eight students participated in each of them. The questions were based on the interview guide, and the data were noted down then and there by the RA with the permission of the participants. The responses were coded and hence anonymized to avoid bias in the course grading. The RA read out her notes at the end of each interview to selected participants to ensure the truthfulness of the data. The transcribed data was checked for clarity by the primary researcher within the same week. The data saturation was obtained by the fifth focus group interview.

2.3.3. Ethical Consideration

Ethical permission to conduct this study was obtained from the institutional ethical committee (REC/2017-2018/10). All the participants were informed about the study and its purposes, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants before commencing the data collection.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Phase

The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23, and the graphs were generated using Excel 2016. The data presented in Table 1 shows that most of the students were female (77.8%), aged 21 years (64.2%), and belonged to the 2016 cohort (66.7%).

| Variable | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 18 | 22.2 |

| Female | 63 | 77.8 |

| Age in years | ||

| 20 | 14 | 17.3 |

| 21 | 52 | 64.2 |

| 22 | 15 | 18.5 |

| Cohort | ||

| 2015 to 2020 | 27 | 33.3 |

| 2016 to 2021 | 54 | 66.7 |

- Note: f = frequency; % = percentage. n = 81.

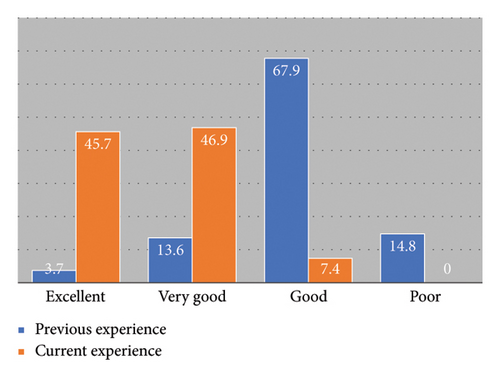

Figure 1 shows that most of the students (67.9%) rated their previous simulation as only good, whereas most of them rated the current mental health simulation experience as very good (46.9%) and excellent (45.7%).

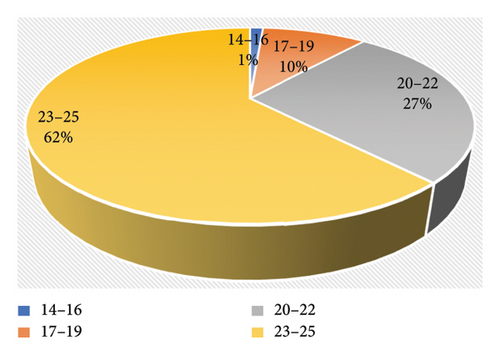

Figure 2 depicts that most of the students (62%) perceived high satisfaction after the completion of the mental health simulation. The highest ranked item around satisfaction was “I enjoyed how my instructor taught the simulation” (total score = 379), followed by “The teaching methods used in this simulation were helpful and effective” (total score = 376).

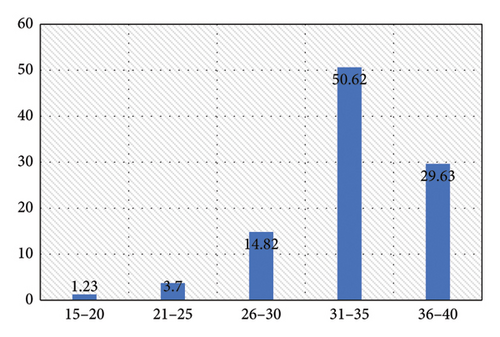

Figure 3 illustrates that most of the students (50.62%) attained very high self-confidence after the simulation practice. The highest ranked item around self-confidence was “I am confident that I am developing the skills and obtaining the required knowledge from this simulation to perform necessary tasks in a clinical setting” (total score = 361), followed by “I am confident that this simulation covered critical content necessary for the mastery of curriculum” (total score = 345).

The data in Table 2 show students’ perceived satisfaction is independent of their gender (p value = 0.373) and age (p value = 0.097), but associated to their cohort or year of joining the course (p value = 0.005), that is, the juniors were more satisfied with the simulation, which is an active learning strategy, than their seniors.

| Variable | Satisfaction | χ2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < Median | > Median | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 12 | 6 | 0.546 | 0.373 |

| Female | 37 | 26 | ||

| Age | ||||

| 20 | 6 | 8 | 2.754 | 0.237 |

| 21 | 32 | 20 | ||

| 22 | 11 | 4 | ||

| Cohort | ||||

| 2015 to 2020 | 22 | 5 | 0.008 | ∗0.005 |

| 2016 to 2021 | 27 | 27 | ||

- Note: χ2 = Chi square; p value = ∗< 0.05; n = 81.

The data in Table 3 shows there is no association between the students’ perceived confidence with their gender (p value = 0.190), age (p value = 0.598), and cohort (p value = 0.530).

| Variable | Confidence | χ2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < Median | > Median | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 13 | 5 | 0.251 | 0.190 |

| Female | 36 | 27 | ||

| Age | ||||

| 20 | 7 | 7 | 0.277 | 0.598 |

| 21 | 33 | 19 | ||

| 22 | 9 | 6 | ||

| Cohort | ||||

| 2015 to 2020 | 16 | 11 | 0.873 | 0.530 |

| 2016 to 2021 | 33 | 21 | ||

- Note: χ2 = Chi square; p value = < 0.05; n = 81.

3.2. Qualitative Phase

The theoretical foundation for the analysis of the data in the qualitative phase of this study is grounded in Braun and Clarke’s [28] framework for thematic analysis (Figure 4). This method involved identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns within data. The steps for thematic analysis were followed in the analysis, such as: familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report. The trustworthiness of the whole process was assured by checking the transcribed data by the primary investigator at the first stage, and later, the themes were validated by the second and third authors and through member checking, where a few participants were asked to review the results. They all confirmed the themes and subthemes as a true reflection of the transcribed data and the participant responses.

Among the participants, out of 48 students, 37 were female (77.08%) and 11 were male (22.92%). A structured thematic analysis of the recorded data was done to derive themes manually. Five themes were derived from the focus group discussions. The qualitative findings substantiate the quantitative findings by validating the participants’ subjective expression regarding their experience in learning through simulation. The overview of the themes and subthemes is given in Table 4.

| Number | Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Overall simulation experience in mental health nursing |

|

| 2. | Advantages of simulated learning |

|

| 3. | Challenges of simulated learning |

|

| 4. | Simulation vs. actual clinical experience |

|

| 5. | Recommended simulated cases and duration |

|

3.3. Theme 1: Overall Simulation Experience in Mental Health Nursing

Most of the student participants verbalized that simulation is a very good, useful, interesting, and good environment to learn clinical skills. Most of the students expressed enthusiasm and appreciation for simulation as a valuable learning tool.

3.3.1. Subthemes

3.3.1.1. Engagement and Interest

“In simulation, we had the chance to act independently, and with instructor feedback, we could practice the skills better.”

“Simulation offered an excellent learning platform for me, where I could practice and correct my skills in taking care of mentally affected clients.”

3.3.1.2. Learning and Confidence Building

“Simulation gave us confidence to deal with the mentally ill patients.”

“My confidence in handling real-life scenarios has increased after attending the simulation.”

3.4. Theme 2: Advantages of Simulated Learning

Mental health simulations using SPs helped the students gain confidence in multiple mental health skills like communication, mental health assessment, leadership, teamwork, and many others. The following subthemes and responses from the students help us understand the various advantages perceived by the participants.

3.4.1. Subthemes

3.4.1.1. Error Correction and Safe Practice

“Learning in a less stressful environment helps me practice without fear of making mistakes, and it increases my confidence.”

3.4.1.2. Exposure to Rare Situations

“Simulation allowed me to practice skills for which I may have had rare exposure in actual clinical postings.”

“We learned many things through simulation that we may not see in the clinical setting.”

“Though I like actual clinical sessions, simulations helped me to understand rare cases like Panic anxiety attacks, and Aggression.”

3.4.1.3. Comprehensive Learning

“Prebriefing actual simulation, and debriefing make my learning about a disease condition complete rather than only selected aspects in clinical posting.”

3.4.1.4. Preparation for Clinical Posting

“Interesting and beneficial learning; a good environment to learn before the actual clinical posting.”

“We could practice everything we have learned in theory regarding the management of patients.”

“Simulation helped me learn how to deal with the patients before I could go to the clinical area.”

“Simulation prepares us for clinical posting, and we know what to focus on during our rotation.”

3.5. Theme 3: Challenges of Simulated Learning

Most of the students are unprepared at the beginning of the clinical placements, and a properly designed simulated experience helps the students bridge their gap between theory and practice. Actor-based simulation is known to boost the student’s confidence if the actor is adequately trained. But there could be certain challenges, like the actor not being very realistic in their expression due to mental or physical exertion or inadequate training. The following subthemes and responses indicate that the students had experienced some of those challenges during their simulated learning experience.

3.5.1. Subthemes

3.5.1.1. Realism and Authenticity Issues

“I felt that the patient was not real; hence, I did not feel an emotional connection with the SP.”

“Sometimes I felt the SP’s actions and talks were very unrealistic, especially in the Panic Anxiety simulation.”

“Most of the time, I was not serious, as I know our SP is not a real patient.”

“As compared to simulation, we are more serious in clinical as we deal with real patients.”

3.5.1.2. Timing of Simulation

“We felt simulated learning before the clinical practicum was more beneficial than after.”

“As the simulation was planned group-wise, our group experienced it after the real clinical exposure, so we could not utilize our simulated learning for real patients.”

“Having a simulation at the beginning of the semester could be very beneficial.”

3.5.1.3. Group Work Dynamics

“In some of the simulations, we worked in groups, so as an individual, I am not sure of my performance.”

3.6. Theme 4: Simulation vs. Actual Clinical Experience

Clinical nursing education helps to integrate theoretical knowledge from the books into real-life situations and builds the problem-solving skills of the students, whereas simulation helps the student nurses gain skills in nontechnical skills, decision making, and rare emergency situations. The participants have contrasted and analyzed both learning experiences under this theme.

3.6.1. Subthemes

3.6.1.1. Simulation as a Safe Practice Ground

“Since it is not the actual situation, we are less stressed to think and act, and we get more time to work on a particular issue.”

“In clinical settings, we are more reserved, as we are not sure when a patient can become aggressive, but in simulation, we are sure that the patient will not harm us.”

“Clinical would be more beneficial, but we could learn many things in simulation as well, and whatever we learned remains in our minds to practice.”

“In simulation, we are not afraid of making mistakes, so our thoughts are clearer to think about and act on.”

3.6.1.2. Clinical Posting Reality Check

“I felt real patient interactions invoke higher levels of responsibility and provide spontaneous learning opportunities.”

“I find myself more emotionally engaged with my patients in the clinical setting than with the SPs.”

“We were more careful and serious about our actions in the hospital.”

3.6.1.3. Integration and Completeness

“We can practice whatever we have learned, and we follow the steps of action in simulation, but in clinical practice, we may not get time to follow all steps.”

“In simulation, we all get a chance to practice, whereas in clinical, mostly we observe, or not all of us will get a chance to practice.”

3.7. Theme 5: Recommended Simulated Cases and Duration

Towards the end of the focus group interview, the students were asked to give their recommendations on the desired mental health simulation scenarios and duration in the future, based on their experience.

3.7.1. Subthemes

3.7.1.1. Suggested Duration

“It would be beneficial to spend more time learning through simulation, at least 30 hours.”

3.7.1.2. Topics for Simulation

“Simulation for aggression management was very good.”

“As we are already exposed to the common mental disorders, simulation for rare cases like aggression, panic attacks, suicide, etc. helped us to understand those better. Hence, suggest continuing the same.”

3.7.1.3. Teaching Methods

“Simulation is the best solution for the shortage of clinical space.”

“We get to see only a few conditions in the hospital, whereas we learn a lot of disorders in the theory course. Through simulation, we can bridge the gap between theory and practice.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Quantitative Phase

4.1.1. Gender Distribution and Cohort Representation

The study revealed that most of the participants were female and aged 21 years. This demographic distribution aligns with global trends in nursing education, where females typically constitute most nursing students [29]. The age and cohort distribution suggest that the study participants were at a similar stage in their education, which could influence their learning experiences and receptivity to simulation-based training.

4.1.2. Simulation Inclusion in Mental Health Nursing

All students (100%) believed that simulation should be included in the Mental Health Nursing clinical learning curriculum. This unanimous support is consistent with the findings of Berragan [30], who highlighted that simulation provides a valuable platform for nursing students to practice and develop clinical skills in a safe environment. The universal endorsement of simulation underscores its perceived importance and effectiveness in nursing education.

4.1.3. Evaluation of Simulation Experiences

The shift in students’ ratings from previous simulations being “good” (67.9%) to the current mental health simulation being rated as “very good” (46.9%) and “excellent” (45.7%) is significant. This improvement may be attributed to enhanced design and execution of the simulation experiences. Studies by Cant and Cooper [31] have shown that high-quality simulations, characterized by clear objectives, realistic scenarios, and effective debriefing, lead to better learning outcomes and higher student satisfaction.

4.1.4. Satisfaction and Instructor Influence

The high level of satisfaction (62%) reported by students after the mental health simulation is noteworthy. The highest ranked satisfaction item was “I enjoyed how my instructor taught the simulation” (total score = 379). This finding aligns with the work of Shinnick et al. [32], who found that effective instructor-led debriefing significantly enhances student satisfaction and learning outcomes in simulation-based education. The second highest ranked item, “The teaching methods used in this simulation were helpful and effective” (total score = 376), further emphasizes the critical role of instructional strategies. The effectiveness of teaching methods in simulation has been well documented, with studies indicating that structured and supportive instruction can significantly enhance the educational value of simulations [33].

4.1.5. Self-Confidence and Skill Development

The finding that 50.62% of students attained very high self-confidence after the simulation practice is indicative of the simulation’s effectiveness in enhancing self-efficacy. The highest ranked item, “I am confident that I am developing the skills and obtaining the required knowledge from this simulation to perform necessary tasks in a clinical setting” (total score = 361), suggests that the simulation provided students with a strong sense of preparedness and competence. This is consistent with the findings of Kardong-Edgren et al. [25], who reported that simulation-based education significantly boosts students’ confidence in their clinical skills and knowledge. The second highest ranked item, “I am confident that this simulation covered critical content necessary for the mastery of curriculum” (total score = 345), reinforces the idea that the simulation effectively addressed essential curriculum components, thereby boosting students’ confidence in their knowledge and skills. Abusabeib et al. [34] reported that the repetitive practice opportunities of simulations enabled the development of mastery over clinical skills, boosting confidence among students in a similar cultural context in Saudi Arabia. Simulation-based learning found to improve students’ satisfaction and self-confidence in Oman [35], whereas lower satisfaction levels during COVID-19, although high-fidelity simulations remained beneficial in Jordan [36].

4.1.6. Association With Demographic Variables

The independence of perceived high satisfaction and self-confidence from students’ gender and age, and the dependence of satisfaction to cohort is an interesting finding. This partially aligns with the research of Harder [37], who found that simulation is an inclusive educational tool that caters to diverse learning needs, providing equitable learning opportunities regardless of gender and cohort. The uniformity of positive outcomes across genders and age underscores the robustness and generalizability of simulation as an effective pedagogical strategy in nursing education.

4.2. Qualitative Phase

4.2.1. Theme 1: Overall Simulation Experience in Mental Health Nursing

The participants’ overall positive perception of the simulation experience highlights its value as an engaging and effective learning tool. Engagement and interest were highlighted by participants who appreciated the opportunity to act independently and receive feedback. This aligns with the findings of Leigh [38], who noted that simulation fosters active learning and student engagement. Consistent with existing literature, students expressed enthusiasm and appreciation for simulation as a valuable learning tool, highlighting its effectiveness in providing a safe and supportive environment for skill development and clinical preparation [8, 10]. Eltaib et al. [23] reported that 91.3% of participants had a positive attitude toward simulation-based learning, recognizing its use and acceptance in Saudi Arabia; this confirms the adaptability of simulation in a similar cultural context to that of Oman.

4.2.1.1. Learning and Confidence Building

The reported increase in confidence following simulation experiences is consistent with other studies that have shown simulation to be effective in building confidence and preparedness among nursing students [39]. High-fidelity simulation Scenarios on psychiatric nursing, which included alcohol withdrawal syndrome, suicide, panic attack, depression, and bipolar disorder, showed reinforcement of classroom learning, translating, and supporting students learning clinical practice. Much literature supports the culture of simulation in nursing education, precisely holding significance in enhancing students’ confidence and performances of clinical skills [40, 41]. Students reported that the simulation kept them constantly engaged, leading to deeper reflection and constant learning.

4.2.2. Theme 2: Advantages of Simulated Learning

The participants also valued the opportunity to practice in a safe environment, which allowed them to make and learn from mistakes without real-world consequences. This finding is supported by the work of Cant and Cooper [31], who emphasized the importance of a safe learning environment in simulation-based education.

Exposure to rare situations: Participants appreciated the chance to encounter rare clinical scenarios, which they might not experience during actual clinical postings. This advantage of simulation has been highlighted by Gaba [42], who pointed out that simulation can expose learners to rare and critical events that are difficult to encounter in real clinical practice.

4.2.3. Comprehensive Learning

One notable advantage identified by students was the opportunity for comprehensive learning experiences afforded by simulation. Through simulated scenarios, students were able to encounter and practice rare or complex clinical situations that may not be readily available in traditional clinical placements. This not only enhances their confidence but also prepares them to deliver more therapeutically and professionally competent care to patients with mental health disorders [11].

The structured nature of simulation scenarios, including prebriefing, simulation, and debriefing, was seen as beneficial for comprehensive learning. This is corroborated by the findings of Jeffries [33], who advocated for a structured simulation framework to enhance learning outcomes. Majority of students reported that simulation enhanced their critical thinking and clinical judgment abilities, which aids in acquisition of clinical skills and to practice confidently and competently [41].

Findings of García-Mayor et al. [18] and Kameg et al. [43] showed that students expressed higher satisfaction rates on specific psychiatric procedures such as therapeutic communication, medication administration, and managing panic attacks after simulation training. The study added the simulation was a keystone for showing proficiency in mental health nursing skills during OSCEs. This corroborates to present study findings where students attribute that simulation enhanced their satisfaction and confidence in clinical practice. A statement often told in the interviews was “My confidence in handling real-life scenarios has increased after attending the simulation.”

4.2.4. Theme 3: Challenges of Simulated Learning

Realism and authenticity issues: Participants raised concerns about the realism of simulations, particularly the portrayal of patients by SPs. This challenge has been noted in other studies, where the lack of realism can affect the authenticity and effectiveness of the learning experience [44]. However, the study also elucidated certain challenges inherent in simulated learning experiences. Students reported initial hesitancy or lack of seriousness due to the artificiality of simulated patients, as well as difficulties in establishing emotional connections or empathy compared to real clinical encounters. These findings underscore the importance of addressing the authenticity and emotional engagement aspects of simulation design to enhance its effectiveness [45].

Despite recognizing the benefits of simulation, students expressed a preference for actual clinical experience, emphasizing its irreplaceable value in integrating theoretical knowledge and problem-solving skills in real-life patient care settings. This strengthens the need for a balanced approach to nursing education that combines both simulation and clinical practice to optimize student learning outcomes [46].

One of the solutions to overcome the students’ perceived challenges in simulation realism is the influence of SP’s preparation during simulation. The credibility of clinical knowledge sustainability lies in the hands of SPs. Trained SPs who had previous employment experiences in psychiatric settings, such as a nurse, patient attender, or students, would possibly help in transferability of clinical engagement to a psychiatric milieu. Furthermore, a well-scripted simulation reflecting realistic settings of patient voices, physical and nonverbal expressions of panic attack patients, hyperactivity, flight of ideas, and therapeutic communication allows students to dwell in the realm of the actual psychiatric ward, as pointed out by Conway and Scoloveno [47].

Timing of simulation: The timing of simulations relative to clinical exposure was another challenge identified. Participants preferred simulations before clinical rotations, which is in line with the findings of Harder [37], who emphasized the importance of timely simulation experiences to maximize their educational impact.

Group work dynamics: Issues with group dynamics and individual performance assessment were noted, with some participants preferring individual simulations. This preference for individual assessment to ensure equitable learning opportunities is supported by the findings of Kardong-Edgren et al. [25].

4.2.5. Theme 4: Simulation vs. Actual Clinical Experience

Simulation as a safe practice ground: Participants appreciated the safe and controlled environment provided by simulations, which reduced stress allowed for focused learning. This benefit of simulation is well documented in the literature, where it is described as a key advantage over traditional clinical education [42].

Clinical posting reality check: Despite recognizing the benefits of simulation, participants still preferred actual clinical experiences for their realism and spontaneity. This preference is consistent with the findings of Bremner et al. [48], who reported that while simulations are valuable, they cannot entirely replace the unpredictability and depth of real clinical interactions.

Integration and completeness: The combination of simulation and clinical experience was seen as beneficial for integrating theoretical knowledge with practical skills. This integrative approach is supported by the work of Cant and Cooper [31], who advocated for the use of simulation to supplement and enhance traditional clinical education. Both the National League for Nursing (NLN) and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) recommend 50% simulation and 50% clinical training into nursing curricula [49]. Simulation, along with traditional clinical learning, would improve practical skills while caring for people with mental illness.

4.2.6. Theme 5: Recommended Simulated Cases and Duration

Suggested duration and topics for simulation: Participants recommended specific durations and topics for future simulations, emphasizing the importance of continued and targeted simulation experiences. This recommendation aligns with the findings of Shinnick et al. [32], who highlighted the need for ongoing simulation training to cover a wide range of clinical scenarios.

Lockertsen et al. [50] emphasize that longer duration of clinical simulation practice contributed to increasing students’ self-awareness and in-depth reflection, broadening their nursing competence. Similar views and recommendations have been formulated by NLN and NCSBN nursing bodies [49]. Although mounting studies support simulation activities in learning clinical competencies, the designated percentage of simulation hours in actual clinical education is under-researched across nursing education. A number of mental health simulation scenarios can keep students more engaged through simulation. The simulation scenarios used are the cornerstone of the mental health student’s clinical core competencies. Reinforcement of this learning shall aid in better clinical learning outcomes in nursing practicum education.

In terms of recommendations, students advocated for the integration of simulation with clinical practice to supplement hands-on learning, particularly in scenarios where opportunities for direct patient care are limited. Specific areas highlighted for simulated practice included aggression management, suicide assessment, and panic attacks that were in par with another study [51].

Teaching methods: The integration of simulation with clinical practice was seen as a solution to the limitations of clinical hours. This suggestion supports the findings of Berragan [30], who argued that simulation can bridge the gap between theory and practice in nursing education.

5. Conclusion

Simulation is a growing pedagogy that can be supplemented along with actual clinical practice to ensure the students have achieved their clinical objectives. The findings of this study provide robust evidence for the effectiveness of simulation-based learning in enhancing satisfaction, self-confidence, and perceived preparedness among nursing students. The unanimous support for incorporating simulation in the Mental Health Nursing curriculum highlights its critical role in contemporary nursing education.

The significant improvement in students’ ratings of simulation experiences and the high levels of satisfaction and self-confidence underscore the importance of well-designed simulations and effective instructional strategies. Moreover, the independence of these positive outcomes from demographic variables such as gender and age and the growing satisfaction in the recent year demonstrate the broad applicability, inclusivity, and rising acceptability of simulation as an effective teaching strategy.

6. Strengths and Limitations

The mixed-methods approach gave a holistic view of the findings, through substantiating and clarifying the quantitative findings by the qualitative interpretations. The study strongly recommends the use of simulation in the mental health nursing curriculum. While this study provides valuable insights into student perceptions of mental health simulation, it is not without limitations. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study focused solely on nursing students at a single setting, which may limit the applicability of the findings to other contexts. Furthermore, the study relied on self-report measures and focus group discussions, which are subject to biases such as social desirability and groupthink.

7. Implications

Students can practice rare or complex clinical situations in simulation that may not be readily available in traditional clinical placements. Specific areas highlighted for simulated practice included aggression management, suicide assessment, and panic attacks, reflecting the importance of addressing essential mental health nursing skills through simulation-based teaching. These insights are valuable for educators and curriculum designers aiming to enhance the quality and effectiveness of nursing education programs.

Ethics Statement

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (REC/2017-2018/10). All the participants read and signed the informed consent before their participation in the study. They all were sanctioned free will to withdraw from the study anytime without any restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the following: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of results, manuscript writing, and submission by Blessy Prabha Valsaraj; writing discussion and revising critically for important intellectual content by Savithri Raman; writing introduction and review of the literature by Divya Kuzhivilayil Yesodharan; and facilitation of simulation by Mohammed Qutishat.

Funding

This study was funded by the Sultan Qaboos University under the Internal Research Grant Budget (IG/CON/CMHD/19/01).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the participants of the study, the College of Nursing Ethics and Research Committee, and Sultan Qaboos University for sanctioning the internal grant funding. They are also grateful to the lab assistants, simulated patients, and mental health department faculty and students for all their support throughout the study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.