Master of Nursing Students’ (MNS) Experiences With Online Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study in an Australian University

Abstract

Aim: To explore and collectively describe Master of Nursing Students’ (MNS) experiences with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Background: While undergraduate nursing students experiences with online learning are well-reported, there remains a lacuna in the literature about MNS experiences.

Design: Descriptive, qualitative study guided by phenomenological approach.

Methods: MNS participants were purposively recruited (n = 12) during the first and second semester of 2020-2021 academic year in an Australian university. We conducted five virtual, semistructured interviews and two focus group discussions. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were thematically analysed and validated via correspondence.

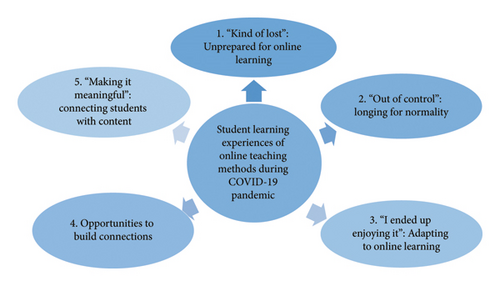

Results: We identified five key themes: (1) “Kind of lost”: Unprepared for online learning, (2) “Out of control”: Longing for normality, (3) “I ended up enjoying it”: Adapting to online learning, (4) Opportunities to build connections, and (5) “Making it meaningful”: Connecting student with content.

Conclusion: While initially felt unprepared and experienced challenges, participants adapted to the new online learning approach over time by gaining new digital literacy skills and self-regulated study habits.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic occurred for three years and has caused significant and lasting transformations in the higher education industry [1]. Globally, the methods used to ensure ongoing education during the pandemic shifted to online learning platforms [2]. Starting in March 2020, Australian universities acted in response to the pandemic by transitioning all classes to an exclusively online format to mitigate the spread of the virus [3]. As of September 2024, Australian universities have more than 1 million international students, representing a 16% increase from before the pandemic [4]. International students, commonly referred to as foreign or exchange students, move to other countries to pursue an educational degree (e.g., bachelor’s, master’s, PhD) [5].

Online learning in higher education is an educational approach in which lecturers and students communicate virtually using a learning management system (LMS) such as Blackboard or Moodle [2, 6]. Online learning has also been referred to as web-based, e-learning, distance, and virtual learning [7]. Nonetheless, online learning is the most used term to describe the various online learning formats available [8].

Online teaching evolved from remote teaching in the 1960s, which started with correspondence programs and telephone-based pedagogy [9]. With the advancement of technology (e.g., mass production and usage of computers, software programs), which was the primary facilitator, face-to-face teaching was transformed into online-based teaching [10]. This method became the most viable means to continue teaching during the pandemic, particularly at the undergraduate and graduate levels [9]. However, numerous drivers and barriers have been reported during online teaching implementation [11, 12]. Several drivers, such as positive experience with online teaching, level of preparedness, pedagogical knowledge and adaptability, and motivation, aided educators in implementing online teaching [11]. Conversely, inadequate experience with integrating educational technology, unfavourable beliefs and attitudes, and lack of technological abilities were reported as significant barriers to online teaching [12].

Online learning and teaching are classified as either synchronous or asynchronous. On the one hand, synchronous online learning refers to environments in which lecturers and students collaborate via online platforms to engage in real-time learning and discussions (e.g., videoconferencing, zoom sessions, webinars) [13]. On the other hand, asynchronous online learning methods provide students with flexibility and convenience regarding material availability [13], typically presented in the form of flipped classrooms, audio or video lectures, e-books, articles, and presentations [14]. The materials are available online, so students can review them whenever they want [15].

1.1. Literature Review

There is no generally recognized distinction between undergraduate and graduate students in teaching and learning approaches [16]. Nonetheless, research suggests that undergraduate students’ approaches to learning are more focused on lower-order abstract cognition or abilities than higher-degree levels [17]. For instance, undergraduates can conduct research, but the project’s scope is restricted, and the study is not expected to contribute to the current body of knowledge. In contrast, graduate students’ learning strategies are more subtle, practical, and multifaceted than undergraduate outcomes. Graduate courses often involve a high degree of abstract thinking (production, evaluation, and innovation) [18]. Therefore, online learning should support students’ learning strategies, whether undergraduate or graduate.

Students’ preparedness is well-documented as a substantial factor in any educational endeavour, regardless of the learning environment (onsite vs. online) [19]. Student preparedness is students’ readiness to transition from one situation to another, from classroom to clinical placements, student life to working life, or onsite to online learning [20]. For instance, allied health students’ who are academically prepared performed better in their clinical placements [21]. Academic preparation to improve clinical performance includes curriculum revisions that incorporate essential clinical skills and simulation sessions from the start, the appointment of peer instructors and mentors, the offering of brief transition programs and clinically related instructional resources, accessibility to clinical instructors, increased hospital excursions, and community projects that begin early and in the preclinical placement phase [21]. Moreover, students’ preparedness, resilience, and engagement directly correlated to a positive online learning experience [19]. Despite today’s students being digital natives, they are still unprepared for planning strategies, synthesizing ideas, making arguments, and working with online learning [22, 23]. Thus, educators should develop and sustain undergraduate or graduate students’ preparedness in any learning environment regardless of an onsite or online set-up.

Students’ preparedness for the online learning environment is crucial to their ability to engage in this form of learning [24]. A prepandemic study in the USA explored the experiences of 43 nursing students who completed four units of an online master’s program using a qualitative narrative method [25]. The results showed that participants indicated high levels of satisfaction with the online learning structure and that these positive expressions were a direct consequence of students consciously opting to study via online methods [25]. Contrastingly, a study exploring the experiences of bachelor’s and master’s nursing students during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic found that online learning was a significant challenge to their studies, leaving them as confused and uncertain as they preferred and an expectation for traditional, face-to-face learning and teaching methods [26].

Accordingly, the most popular online methods among nursing students in the USA were the discussion forums, and the most engaging method was online videos or presentations, whilst the least engaging method was collaborative work [27]. This research, however, was significantly limited by over half the participants not having previously experienced online learning strategies such as games, FaceTime, simulations, and chat forums. This emphasizes the importance of the availability of different online learning and teaching methods to accommodate various individual learning styles. For example, in a prepandemic study in the USA, Foronda and Lippincott [25] explored the learning experiences of 43 Master of Nursing students (MNS) who completed four online courses, reporting high satisfaction levels with the online learning format.

In a recent systematic review, the enablers and barriers of online learning in health sciences education found the most frequently reported barrier was a lack of digital literacy [28]. Digital literacy is the ability to locate, analyse, and disseminate data utilizing technology [29]. Universities must prepare undergraduate and graduate nursing students for employment in a digitalized academic and clinical setting [30]. Moreover, a recent scoping review in nursing education found that insufficient infrastructure to support using computers and tablets led to poor self-confidence and satisfaction with online learning and teaching methods [31]. This situation was further compounded when there was a lack of direct communication between teaching staff and students [31–33]. The enabling factors, on the other hand, were easily accessible materials [34].

Online learning is presumed to be flexible regarding time, space, cost, and impact on personal lives [35]. Accordingly, online learning promotes access to learning materials and increases collaboration opportunities, which is impossible with conventional teaching methods [36]. Therefore, when utilised successfully, online learning methods can more easily facilitate content, commitment, and connections.

Online learning experiences among undergraduate nursing students were well-reported in the literature [37, 38]. Bloom’s taxonomy of learning could serve as a tangible theoretical framework for the teaching and learning approaches between undergraduate and master’s students [39, 40]. For instance, the higher order thinking (e.g., evaluate and create) in Bloom’s taxonomy is the primary target to develop among master’s students [41]. They should develop the competence to judge the value of ideas, concepts, and information, synthesizing and combining these concepts to create new perspectives or constructs to advance a better understanding that will generate more evidence to improve professional practices. Master’s students are expected to exhibit higher levels of self-directed learning during online classes [42]. However, exploring their experiences during online courses is crucial to developing programs and policies to enhance learning engagement and prevent attrition. Master-prepared nurses are vital in educational and healthcare settings because they are positioned in leadership and management roles. Their invaluable presence could influence the quality of nursing education and patient care and achieve organizational outcomes [43]. However, a dearth of reported experiences with online learning during the pandemic remains among a cohort of MNS. Hence, this qualitative study sought to answer the question, “What are the collective experiences of MNS on online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic?”

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study used a descriptive, qualitative design guided by a phenomenological approach. In qualitative research, the emphasis is on acquiring a description of “lived experiences” through the appraisal of participants’ ideas and beliefs [44]. In relation to the study of human experience, phenomenology reaches beyond the description to encompass the essence of the subject, thereby examining the core concepts to find meanings that are an essential part of the experiences in question [45]. This design employs the descriptive phenomenological approach to obtain a holistic, detailed description of the participants of interest; inductive and naturalistic approaches were applied [46]. This design aims to understand in depth the specific experienced phenomenon and how other participants experience this phenomenon under certain situations [46]. In addition, phenomenology can provide in-depth interpretations of the meaning and structure of experiences [46].

The COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist (Supporting File 1) was used to guide the reporting of our study [47]. This checklist ensured all qualitative study elements were addressed before reporting study results. Thus, researchers are guided to present key research components (i.e., methods, results, analysis, interpretations, limitations, and generalizability) and are cognizant of the research objectives, resulting in a transparent and unbiased investigation reporting [47].

2.2. Setting, Participants, and Sampling

The inclusion criteria were domestic or international master’s degree nursing students who completed the GHS5841 unit online and in the first or second semester of 2020. Those who did not satisfy the inclusion criteria were excluded from the study. Participants were purposively recruited from one of the largest Australian universities. A total of 16 students completed the preliminary questionnaire of whom 12 consented to being involved in in-depth, individual interviews or focus group discussions (FGDs) (Table 1). The main reason students declined to participate in the interview was the heavy hospital clinical workload.

| Pseudonym | Age (in years) | Preonline learning experience | Type of student | Gender | Marital status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | > 40 | No | Domestic | Female | Married |

| P2 | 20–30 | No | International | Female | Single |

| P3 | 20–30 | No | International | Female | Single |

| P4 | 20–30 | Yes | International | Female | Single |

| P5 | 20–30 | Yes | International | Female | Single |

| P6 | 31–40 | Yes | International | Female | Single |

| P7 | 31–40 | No | International | Female | Married |

| P8 | 20–30 | Yes | International | Female | Married |

| P9 | 31–40 | No | International | Male | Separated |

| P10 | 20–30 | No | International | Female | Single |

| P11 | 20–30 | No | International | Female | Single |

| P12 | 20–30 | Yes | International | Female | Married |

- Note: P: participant.

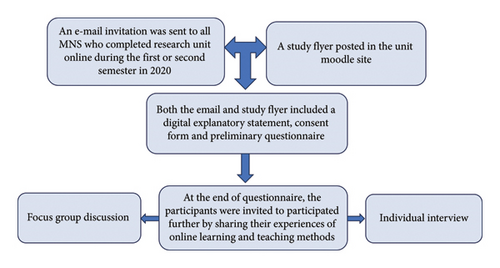

We used purposive sampling to recruit eligible student participants whose learning was converted to online methods in 2020 (Figure 1). Purposive sampling allows a genuine real-world understanding of people’s experiences [46]. Both domestic and international students were invited and included in the sample.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was sought and obtained from the XXX University Human Research Ethics Committee (No.: 26,197, approved 26/10/2020). Informed consent was obtained from all study participants before the interviews, and confidentiality and anonymity were assured. All collected data were stored in a dedicated laptop protected by a password accessible only to the primary investigator. We immediately anonymized the data and ensured that no identifying information of the participants was linked during manual transcription and data analysis.

2.4. Data Collection

Before the individual interviews and FGDs, the first author sent a preliminary online questionnaire to students who expressed an interest in the study. The questionnaire gathered information on students’ age, gender, prior online experiences, and enrolment status at the university (international or domestic). The questionnaire incorporates a five-point Likert scale, wherein 1 denotes “least effective” and five signifies “most effective.” Participants were questioned about nine online learning and teaching methods they experienced during the GHS5841 unit. Two more open-ended questions focus on the barriers and enablers of online learning and teaching methods. The data was used to guide the interview and FGD questions. See the flowchart (Figure 1) of the recruitment of study participants.

The researchers created the questions in this preliminary questionnaire based on the extensive literature review about online learning and the description of the online learning course the participants took up. The contents of the questionnaire were validated by the three professors with doctorate degrees and extensive online teaching experience in Australia. The results of this preliminary interview guided the creation of the final interview-guide questions.

The interview questions included six open-ended questions (e.g., Can you please tell me about your learning experiences of online learning and teaching methods during the period when all learning was forced online due to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdown? Can you tell me what you believe would have improved your learning experience of online learning and teaching methods? If you were asked to provide a student with advice regarding online learning, what would it be?) to elicit information on the barriers and enablers of online learning methods. These methods included group discussion, zoom meetings, pre/post class activity, presentations, videos, and assignments. Student participants were also asked to make recommendations for improvements to online learning methods and were invited to an individual interview and/or FGD [48].

The FGDs and individual interviews were conducted from November 2020 to February 2021. All individual interviews and FGDs were done virtually via the Zoom platform at a suitable time nominated by the participants. Five students agreed to individual interviews ranging from 15 to 32 min, whilst four focus groups were facilitated, which lasted between 48 and 66 min. All interviews and FGDs were conducted in English and audio-recorded with consent. All interviews halted once we reached data saturation [46, 48], where no new information and themes were obtained, and participants shared the same experiences. Thus, a sufficient sample size was reached in this qualitative study [46].

The same interview-guide questions were used for the individual interview and FDG groups. We used two data collection techniques (individual interviews and FGDs). Firstly, to obtain in-depth information about the topic of interest [48]. Secondly, students who prefer not to engage with the FGD can perform individual interviews. On completion of the preliminary questionnaire, participants were invited to leave their details if they were interested in participating in an individual interview and/or FGD and could choose the most convenient interview methods. No significant challenges were encountered as the interview/FGDs were conducted online at a convenient time for the participants. However, we found that participants more engaged in sharing their experiences during the FGD, as the interview was during the COVID-19 lockdown period, and they were interested in sharing their experiences with others.

2.5. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the transcripts, starting with reading and re-reading the interviews, developing initial codes, collating all similar codes or meanings, then organizing them into themes and subthemes [48]. The first author (Khatmah Alatawi) conducted the initial coding of the interviews. Then, other authors (Gabrielle Brand and Kerry Hampton) conducted a coding for a random selection of the interviews and coding theme. Data were manually sorted for comparison and consensus reached by all authors to generate the final themes. We validated the findings through correspondence. The findings were sent back to three participants to examine and validate; all responded that they concisely reflected their experiences. Thus, validating our data analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Participants Demographic Characteristics

More than half of the study participants were aged between 20 and 30 years, primarily female and single, with 70% indicating they had no online learning experiences. Eleven were international students from China (n = 4), Saudi Arabia (n = 5), Oman (n = 1), and Mexico (n = 1). Only one participant was a domestic student (Australian) (Table 1). There were seven and five participants enrolled in the first and second semesters, respectively. One domestic student shared the same experiences as the other participants. Her online experiences were more positive because she worked at the hospital and studied online to save time. Moreover, we found no different or diverging experiences relative to their semester at the university. We interviewed at the end of the semester, so they had similar experiences for both semesters.

3.2. Themes

Five major themes emerged from the interview data: (1) “Kind of lost”: Unprepared for online learning; (2) “Out of control”: Longing for normality; (3) “I ended up enjoying it”: Adapting to online learning; (4) Opportunities to build connections; and (5) “Making it meaningful”: Connecting student with content (Figure 2).

3.3. “Kind of Lost”: Unprepared for Online Learning

Student participants were uncertain about the online learning format in the first couple of weeks, describing their initial shift to online learning as “challenging.” None of the participants had planned to study online, and the international students did not have the option to remain in their home countries and continue their studies online.

“It was challenging for us nurses. We love hands-on practice, but we don’t like dealing with computers. So, it was my first time dealing with computers for study purposes.” (P4)

“I still remember the first day. I was about to attend the class but didn’t know how to join Zoom. I was not familiar with the system. It was confusing, so I didn’t attend the first class.” (P5)

“It was just tough to adapt because the way I learned in my home country was very traditional. It was more with teachers in the class, so it was difficult first to adapt to the active learning and the online education.” (P6)

3.4. “Out of Control”: Longing for Normality

“This online environment creates something specific for us international students because we are not proficient in English. So, when facing almost 20 students with two lecturers, you hesitate and feel afraid to talk.” (P11)

“I don’t think studying online is a challenging experience, but the lockdown makes it more challenging because we cannot go outside. We always feel lonely and isolated due to the lockdown, but not due to the online learning.” (P4)

“I am a mother of three children, and they were home learning during the lockdown. It was difficult for me to do their home learning and do my study at the same time.” (P2)

3.5. “I Ended Up Enjoying It”: Adapting to Online Learning

“It was challenging at the beginning, but I ended up enjoying it in the second semester.” (P5)

“It is flexible. So, any time I want, I can see the recorded Zoom sessions. I don’t need to attend live Zoom sessions.” (P11)

“It taught me discipline-how to be always on time and do your assignments on time. By the end of my academic journey, it taught me how to exercise self-discipline without a supervisor or someone telling me what to do.” (P4)

3.6. Opportunities to Build Connections

“I think the Zoom session online offered the most engagement for me because it was closer to the face-to-face class method.” (P3)

“It was helpful to know what other people were doing and how things were going for them within the unit. They put us in the breakout room and gave us tasks to do together. So, when we finished, we talked about our lives and how we were doing.” (P4)

“I like the online discussion forum because everyone can participate and ask any question, and the other peers can benefit from the question. Also, if the lecturer doesn’t answer the question quickly, another peer can answer if they are sure about their information. So, you don’t feel lonely studying this unit.” (P9)

“Nobody replies, but it’s for the lecturer to reply to our questions. I suppose the problem might be not having the correct information.” (P11)

“I had a personal Zoom meeting with our teacher. She just guided me and scheduled online Zoom meetings after I arrived here. She told me what would happen in the live Zoom sessions, which was why I was impressed with the content.” (P5)

3.7. “Making It Meaningful”: Connecting Students With Unit Content

“I like videos because I am quite a visual learner, and I can repeat it again and again. I think this method is effective.” (P12)

“I went to YouTube sometimes, just to search. Sometimes I went to the same presenter. I prefer the people who present work using my learning style.” (P7)

“I found that the PowerPoint presentations were one of the most helpful and effective teaching methods because the lecturers make them very concise and to the point and give it to you.” (P2)

“I prefer to read textbooks rather than reading on screen.” (P2) “I love reading, especially when I am given the summary of what I need to know.” (P6)

Clearly, each MNS has its own preferred learning styles and experiences of online learning, including establishing ways of learning and understanding the unit content using an appropriate and individual learning style.

4. Discussion

In this study, the main aim was to collectively describe the MNSs’ experiences of online learning in an Australian university. Overall, expectations of the university experience were that they would attend classes in a face-to-face setting. However, during COVID-19, they were forced to engage in a learning environment entirely online for the pandemic. This finding is consistent with Ramos-Morcillo et al.’s [26] study. They reported that students were unprepared for this shift and felt uncomfortable with the sudden and unexpected change to online learning necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This feeling of being unprepared was not just about the surprising shift to online learning but other factors, too, including limited prior online learning experience, being used to passive learning styles, underdeveloped digital literacy, and most participants having English as a second language. Universities and educators should introduce orientation programmes for new online students to help them set realistic expectations and introduce the various benefits of online learning and teaching. This recommendation is consistent with other recent studies outlining the benefits of online orientation programmes in increasing digital literacy skills [49].

During the pandemic, students also reported feelings of “loneliness” and “isolation,” which negatively impacted their mental health. Our findings are consistent with other studies during the pandemic that found that international students who were separated from their families, loved ones, and usual social support systems reported poorer mental health during university learning experiences [50–52].

However, over time, the “kind of lost” feeling was replaced with a greater sense of self-confidence as they became more familiar with online learning formats. Students adapted to this new format in three main ways: becoming more self-regulated, improved digital literacy skills, and a greater appreciation of the flexibility and accessibility offered through online learning methods. These findings are supported by the work of Ramos-Morcillo et al. [26], who also found that, after a few weeks of online study, students began to acclimatise to the confined conditions related to lockdown and the various implementations of the new online learning methods, being able to accept online learning as the “new normal.” These study findings corroborated Khalil et al.’s [53] reports. They uncovered that online learning allows students to use their time more efficiently to achieve their personal goals. Conversely, some students who had children noted that home-schooling their children hindered their abilities to manage their time and self-regulate their studies [53].

Our study found that students valued real-time interaction, peer support, and lecturer support through effective and diverse online learning and teaching methods that underpinned the establishment of effective online learning communities. Over time, the students in our study became more actively engaged in Zoom sessions. They began to consider these sessions to be akin to face-to-face participation without the need for physical attendance. While students in lockdown felt that their needs for real connections were not initially being met, they also identified that online sessions offered a substitute connection with their lecturers and peers. Other benefits of Zoom included rapid feedback and the opportunities to ask questions and/or clarify weekly unit content. Our study participants emphasised the importance of active and regular online participation and communication with peers to ensure they were engaged in sharing opinions or knowledge during Zoom sessions.

Our study found that including various learning resources, such as research articles and visual and auditory teaching materials, facilitated a rich online learning environment. These resources improve student connection with the unit content, especially when supplemented with guidance, tips, hints, and various forms of feedback [54]. Through such content, the flipped or active classroom allows students to interact at any time, from any location, using any connected online device [55, 56]. University courses and unit designs should utilize various online learning methods to ensure that the content is meaningful and delivers a comprehensive understanding.

One of the most interesting findings that emerged from this study is that different learning methods presented within the flipped or active classroom approach, including PowerPoint presentations, research articles, and videos, can be used to scaffold the reactivation of prior learning and assist students in making sense of new content. These methods encourage deeper learning and effective connections with the unit content. This finding suggests that it might be advisable to scaffold content across the semester by using different online learning methods to support cyclic learning, thus simultaneously addressing the diverse nature of individual learning styles and promoting the interactive engagement of students with online resources. As Boling et al. [57] noted, appropriate online use of multimodal elements is essential to successfully developing unit content and student learning.

Our findings illustrate the challenges experienced by MNS during online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic. They encountered several challenges with online learning, such as uncertainties and lack of prior experience with its use. A positive experience with online teaching (e.g., an online instructor who is helpful and creates lively teaching materials and a user-friendly LMS) is a critical driver to overcome challenges brought by online learning [11, 12]. Whether undergraduate or postgraduate, students face barriers and facilitators in adapting to the sudden transition to online learning [58]. Undergraduate nursing students reported issues such as lack of hands-on clinical experience, difficulties with internet access, and the need for more training in e-learning [59, 60]. They also experienced psychosocial problems like stress, anxiety, decreased motivation, and feelings of isolation [60]. Postgraduate students had a more positive experience overall. They showed a higher preference for online surveys (76% compared to 71% of undergraduates) and generally had better experiences with e-learning [59]. Postgraduate students also demonstrated a stronger behavioural intention to use online learning, with performance expectancy being the most significant factor influencing their attitude [61]. In contrast, undergraduate students, particularly prelicensure students, faced more challenges in virtually completing their required clinical hours [62]. They reported increased frustration, decreased accountability, and engagement during remote learning compared to their postgraduate counterparts [63]. Undergraduate students also strongly desired more hands-on, in-person education and postgraduate support [64].

While both groups faced challenges, postgraduate nursing students appeared to adapt more readily to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, possibly due to their prior experience and higher level of academic maturity. Undergraduate students, especially those in prelicensure programs, struggled more with the lack of hands-on clinical experience and the transition to virtual learning environments [2, 26, 31].

4.1. Limitations and Recommendations

The study has two limitations. Firstly, study participants were recruited from only one higher education institution. Secondly, most of the participating students were international students, and therefore, their experiences may not be transferable to domestic students, as they are likely to have had different learning needs and experiences during the shift to online education. Therefore, findings may only be generalizable among the study participants and must be interpreted cautiously.

In light of the limitations, we recommend democratizing the demographics (e.g., multiple graduate programmes, increasing the number of domestic and other international students). Future studies may also explore master students’ learning difficulties (e.g., dyslexia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia) to understand their distinct needs comprehensively. A multisite setting and a larger number of participants would also increase the rigor and generalizability of future studies. Lastly, a mixed-methods design would enhance the rigor of the approach to how future studies will be conducted.

5. Conclusion

We found that the initial online learning experience was challenging for students. However, the level of challenge decreased over time as students gained knowledge and experience with the online learning format. This study highlighted that MNS could adapt to an online learning format and see several benefits to this approach. This study outlines the first exploratory steps regarding the learning experiences of MNS with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a starting point for further research in online learning and teaching methods.

Therefore, the study findings highlight two crucial key points. Firstly, higher institutions should provide clear policies and guidelines (e.g., online consultation with online learning experts and mentoring programs) to support graduate students’ online learning needs. Secondly, educators could build online student engagement by offering an inclusive learning environment where constructive feedback, interactive assessments, and respectful collaboration are valued [65].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the Master of Nursing Students Monash University, Australia, for their participation.

Supporting Information

Supporting File 1: COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research) Checklist.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.