Sociodemographic Factors and Resilience in COVID-19 Vaccine Doses in the Spanish Population

Abstract

Introduction: The pandemic has caused an indisputable level of global suffering, with drastic changes in the daily lives of citizens.

Aim: To describe the sociodemographic characteristics and degree of resilience in a sample of COVID-19 vaccine acceptors versus a sample of vaccine refusers.

Method: A descriptive design was used. The sample comprised 793 women and 207 men (n = 1.000; age 18–79 [mean = 40.43]). The study variables were sociodemographic variables; work-related variables, such as working or not in a health centre; loss of loved ones in the health crisis; levels of resilience; and pro-vaccine beliefs. The instruments used were the Resilience Scale and a set of ad hoc questions created to obtain specific information on beliefs regarding the vaccine and sociodemographic factors.

Results: Individuals with low resilience (92%–98%) and those with high resilience (87%–92%) chose to be vaccinated two or more times. The distribution of variables with the highest frequency of vaccination was in participants over 50 years, with no difference between the genders. A higher vaccination rate has been observed in medium-sized cities (more than 90% who have decided to get vaccinated (two or more vaccines). The highest scores in the acceptance of vaccination are related to belief in the obligation of mass vaccination and working in a health centre (both workers with low and high resilience, more than 95% have received two or more vaccines).

Conclusions: Great sociodemographic variability was shown in the distribution of vaccines and the importance of analysing the cognitive variables involved in the acceptance of vaccines to increase the population’s adherence to vaccination campaigns. Beliefs regarding vaccination were seen as an indispensable element when considering raising the population’s awareness of vaccination. The global priority must be develop strategies that increase the credibility of health policies, with rigorous and scientific information to increase vaccination.

1. Introduction

Lockdowns, social distancing, the use of face mask and vaccination, accompanied by the presence of controversial information, were some of the global measures adopted to curb the virus. Regarding the controversial measure of vaccination, at the start of 2023, there were differences in the percentage of vaccination across different geographical areas worldwide. The highest vaccination uptake rate was in Latin America with 87.07%, followed by Asia with 79.06%, North America with 77.26% and Europe with 76% [1].

The proposed measure of mass vaccination to contain the virus caused certain controversy and mistrust in the population despite a large majority opting to be vaccinated. However, some authors showed that an interesting statistical percentage rejected vaccination and had thoughts of distrust regarding COVID-19 vaccination.

Indeed, the authors in [2] showed how participants of their study (68.6%) stated they were hesitant about the COVID-19 vaccine. A significantly higher rate of hesitancy was observed in the age group of 20–39 years, those who did not have COVID-19 vaccine and those who did not think the COVID-19 vaccine is protective. Also, in subsequent research studies, the authors in [3, 4] observed that 58.4% of the participants of their study had reservations about COVID-19 vaccination and 19.6% were hesitant about all childhood vaccinations.

The authors in [5] investigated the cognitive, ethical, social and political aspects involved in vaccine rejection. Their research demonstrated how vaccination, publicized and promoted through the media and public policies, generated cognitive distortions in a large number of people, leading to their rejection and disbelief in the degree of vaccine efficacy.

The authors also evidenced how, at the ethical level, people tend to perceive what is more beneficial for a greater number of people as fairer, as well as the health-policy decisions that have included experts as well as the people affected. According to this research, accountability and transparency are also the political elements that are key to the successful acceptance of vaccination by the general population.

Through various studies since 2017, the authors in [6] analysed how conspiracy theories that generate rejection towards health recommendations, including vaccination, satisfy basic psychological needs. They explained that in the face of confusion, rumours and situations of uncertainty, conspiracy theories attract more followers and that to avoid this, clear and transparent policies should be developed, as well as a global and agile access for citizens to scientific information.

Reference [7] delved into the sociodemographic characteristics and beliefs associated with vaccination avoidance in a sample of 2,175 Spanish adults to determine the relationship between vaccination fear, needle-related fear, vaccination intention and vaccination avoidance. The highest percentage of rejection of this measure against COVID-19, with a prevalence of 5.1%, was found in young women without dependents in charge, with a high fear of needles, strong beliefs in pandemic-related conspiracy theories and with low vaccination intention. However, the relationship between needle-related fear, vaccination fear, reasons for avoiding vaccination and vaccination intention was low, although significant.

In relation to vaccination refusal, the authors in [8] analysed the situation of university students in Malaysia. Their results showed that only 2% of the sample had not been vaccinated because of concerns about safety and distrust in the messages conveyed by public agencies and the media. Vaccine rejection, in addition to having a varied and significant sociodemographic distribution, was also associated with suffering from mental health problems. However, authors such as [9] did see a more specific sociodemographic profile in the acceptance of vaccination, observing how women, having a chronic illness and being exposed to the COVID-19 virus, increased the probabilities of getting vaccinated.

Continuing with the interest of analysing the variables associated with the rejection or acceptance of the vaccine, there is no robustly clear consensus on the sociodemographic, cognitive and experiential factors associated with greater vaccine acceptance and positive coping attitudes towards government measures in the COVID-19 health crisis.

Some authors, such as [10], suggest that middle-aged individuals with a higher education level and who were exposed to the risk of infection in the workplace, used more effective cognitive and behavioural coping strategies, being more responsive and following World Health Organization guidelines.

Reference [11], for example, presented conclusions on this topic with respect to the Brazilian population and their following of global health recommendations. They found that adults that disagreed with the position of their president, with high levels of altruism, active coping capacity and who belonged to, or lived with members of, risk groups, showed greater engagement with global health recommendations to deal with the pandemic, including vaccination.

Reference [12], coinciding with previous findings, reported that, in the United Kingdom, the highest rates of vaccine hesitancy were associated with younger age, female gender, lower income and lower adherence to other measures against the virus, such as social distancing.

Reference [13] examined adolescents and young adults in Portugal, and their findings also corroborated with the hypothesis of Freeman, with only around 55.6% of this population believing COVID-19 vaccination to be an obligation.

In relation to psychological variables that can improve adaptation to crisis situations such as the one caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic, it is interesting to highlight resilience. Decades of studies affirm the relationship between people with high resilience and adequate coping, and potentially traumatic situations, even with the development of even greater mental strengths after suffering events such as natural disasters or pandemics. For example, the authors in [14] explained how most people become stronger by fighting the difficulties they face through psychological resilience.

In this sense, the authors in [15] showed that resilience predicts psychological well-being and therefore reduces the risks of mental health problems, protecting, for example, against post-traumatic stress after a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the scientific authors [16–20] were focussed on demonstrating the impact between high levels of resilience and the preservation of mental health in times of crisis. However, we observed that it was necessary to see if the acceptance of the measures implemented by the Spanish government could be correlated with a high resilience.

The aim of the present study was to shed light on the characteristics of those who have followed health recommendations in Spain with regard to vaccination and the number of doses administered. Our aim is to shed light, using the ample sample recruited, on how associated sociodemographic factors, experiential factors during the pandemic, as well as participants’ levels of resilience affect the rate of COVID-19 vaccination.

2. Method

The study conducted was quantitative and descriptive. All of the participants were informed of the aims of the research and the voluntary nature of their participation in the research. Their anonymity was also ensured. The data analysis was descriptive, aiming to establish the distribution of the number of vaccines administered in relation to the variables described. The data were analysed using the SPSS 29 statistical software package.

The participants received information about the study and gave their consent to participate. They were sent the online research questionnaire via social media and email. The inclusion criteria were: aged over 18; being digitally capable, as the survey was to be completed online; having been informed of the purpose of the study; voluntarily giving consent and completing the questionnaire; persons of any gender; disability or dependency status; level of education; and health condition, provided these did not prevent them from participating online in the research.

The study sample comprised 1,000 participants (793 women and 207 men). The mean age was 40.43 years, with a standard deviation of 12.24 and a maximum and minimum age range of 18–79 years (208 were aged 18–30 years, 442 were aged 31–45 years and 305 were aged 46–60 years, with 45 participants being older than 60).

With respect to the place of residence, it is worth noting that 190 (19%) of the participants lived in municipalities with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants, 445 (44.5%) lived in municipalities with between 5000 and 50,000 inhabitants and 365 (36.5%) lived in municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants.

In relation to COVID-19, 511 (51.1%) of the participants had been infected with COVID-19 prior to the survey. Of these, 50.7% were male and 50.2% were female. A total of 115 (55.7%) were aged 18–30 years, 236 (53.3%) were aged 31–45 years, 135 (44.2%) were aged 46–60 years, and 23 (51%) were aged over 60 years.

3. Variables and Instruments

3.1. Sociodemographic

The participants were asked about their gender and age.

Experiential variables related to the pandemic. The participants were asked whether they had had COVID-19, whether they were considered vulnerable or lived with vulnerable individuals, whether they worked in healthcare environments and whether they had lost someone close due to the virus (all with dichotomous questions with a yes or no answer). Examples of questions: Are you dependent and/or disabled? Yes/no. Do you work in a health centre? (whether as a healthcare professional or otherwise). Yes/no.

Do you live with any person at risk at a health level? (due to immunosuppression, pregnancy, chronic illness, etc.) Yes/no.

Beliefs about mandatory vaccination. Participants were asked about their position on the mandatory nature of the vaccine on a scale with agreement ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 was “strongly disagree” and was 5 “strongly agree.”

Doses of vaccines received. Participants were asked how many times they had been vaccinated (0–4).

3.2. Resilience

This variable was measured using the standardized “Resilience Scale” [21, 22], which comprises 14 items in both the original version and the Spanish adaptation. Each item is scored on a range from 1 to 7, with 1 being “strongly agree” and 7 being “strongly disagree.” To classify participants as being of low or high resilience, the cut-off for low/medium resilience was set at 82 points. Participants scoring more than 82 points were considered to present high resilience, according to the guidelines for the Spanish version. The data show the scale has adequate internal consistency (α = 0.79).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The analysis was carried out through a descriptive study aiming to establish the distribution of sociodemographic variables with the psychological variables described. All analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS 29 software and PROCESS 4.0 plug-in.

4. Results

Pearson’s bivariate correlations with participants’ vaccination dose scores are presented in Table 1. Higher scores for the acceptance of vaccination to stop the virus are related to the following variables (i.e., age, belief in obligation of mass vaccination and belief that the virus don’t exist). However, the highest vaccination acceptance scores do not have a significant relationship with the rest of the variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How many doses of COVID-19 vaccine have you received? | 1 | |||||

| Mental health perception | −0.023 | 1 | ||||

| Resilience | −0.022 | −0.207 ∗∗ | 1 | |||

| Belief that virus don’t exist | 0.148 ∗∗ | 0.044 | −0.077 ∗ | 1 | ||

| Belief in mandatory vaccination | 0.344 ∗∗ | −0.005 | −0.036 | 0.035 | 1 | |

| Age | 0.080 ∗ | 0.007 | 0.069 ∗ | −0.007 | −0.049 | 1 |

- ∗The correlation is significant at the level 0.05 (bilateral).

- ∗∗The correlation is significant at the level 0.01 (bilateral).

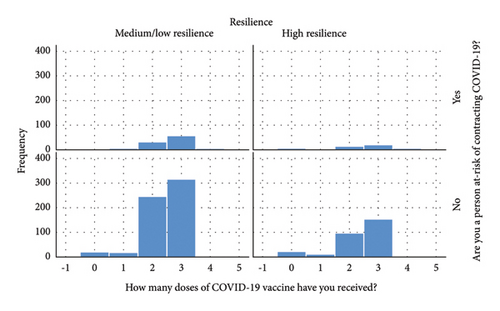

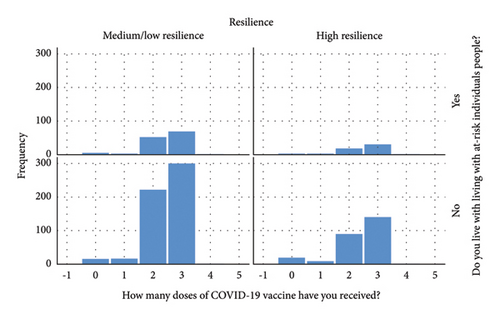

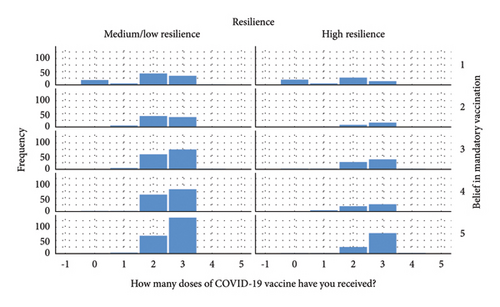

The figures below detail the data obtained for the different sociodemographic and experiential variables and the level of resilience of the sample in relation to the number of doses of vaccination administered.

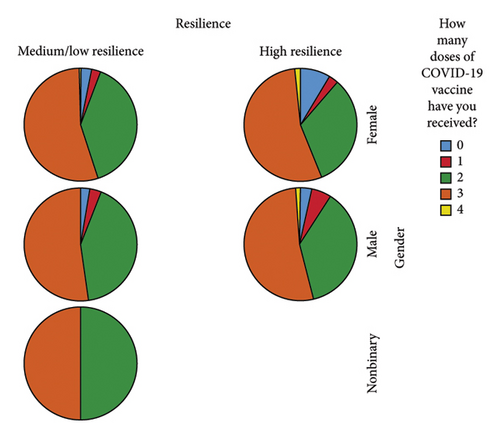

Figure 1 shows the number of vaccination doses received; no significant differences were found between people with high or medium/low resilience, since the frequency at both levels of resilience who have received three or four vaccination doses is similar. In reference to gender, no significant differences were found in the established frequency, being somewhat higher in the female gender. The distribution of the frequency of the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses variable is not significantly different depending on sex (χ2 = 3.495; p = 0.899).

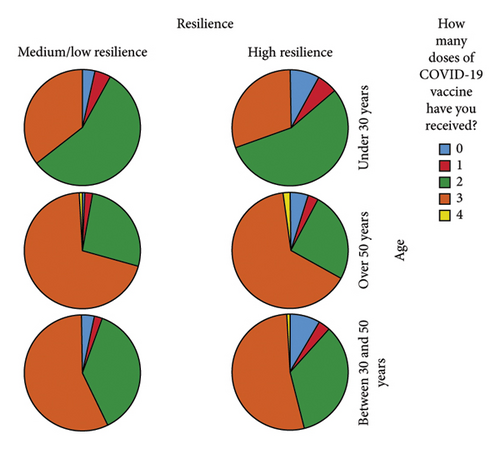

Figure 2 shows that with reference to age, we see a greater frequency of vaccination in those over 50 years of age, specifically three doses of vaccination, with those under 30 years of age, both at high and medium/low levels of resilience, being the highest percentage found in two doses of vaccination. The age range between 30 and 50 years stands out, where among the people with medium/low resilience, 57% of that population received three doses of vaccination. The distribution of the frequency of the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses variable is significantly different depending on age (χ2 = 57.358; p = 0.000).

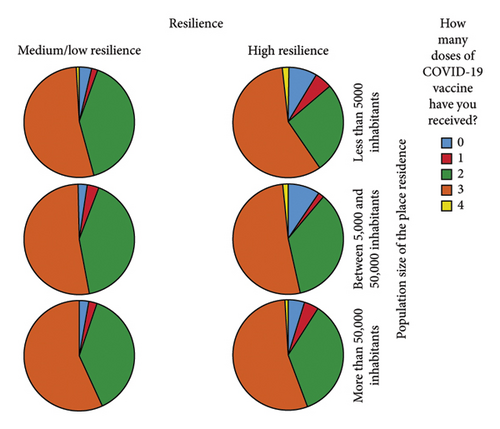

As can be seen in Figure 3, regarding the type of population in which the surveyed participants live and their distribution between the vaccine doses received and their score on the resilience scale, we see controversial results. On the one hand, the number of vaccines received is notably higher in medium-sized cities with more than 5,000 inhabitants. However, if the level of resilience of the participants is not taken into account, there has been greater vaccination in large cities, and the least has been in the most rural areas. The percentages have an irregular and insignificant distribution, so there is a fairly diverse distribution in the vaccine doses received regardless of the type of population and its resilience score. The distribution of frequency of the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses variable is significantly different depending on resilience (χ2 = 322.271; p = 0.008).

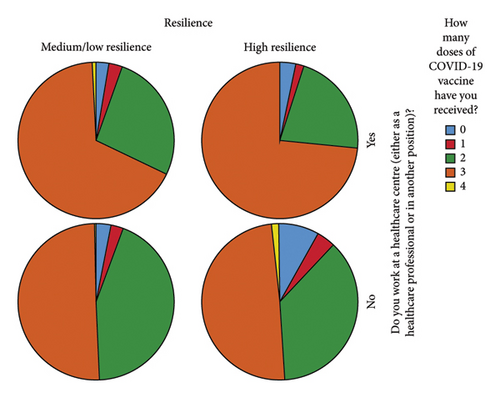

Figure 4 shows that, for healthcare workers, there is no difference between those with low resilience and those with high resilience, with 95% in both cases having decided to have two or more vaccinations. The vaccination rate of health workers compared to non-health workers is also slightly higher for those with low resilience, 95% compared to 94% for those with low resilience and 95% compared to 88% for those with high resilience. The distribution of frequency of the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses variable is significantly different depending on being a healthcare employee (χ2 = 23.471; p = 0.000).

Figure 5 shows that people with a health risk follow the previously observed trends. The percentage of individuals that decided to be vaccinated (two or more vaccinations) is slightly higher among those with low resilience (96%) compared to those with high resilience (91%). In addition, in both cases, it is 2% higher than among those that present no health risk. However, the distribution of the frequency of the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses was not significantly different depending at-risk individual (χ2 = 0.423; p = 0.981).

As can be seen in Figure 6, the percentages of individuals living with people at risk are exactly the same as in the previous case. The number of people that decided to be vaccinated (two or more vaccinations) is slightly higher among those with low resilience (96%) compared to those with high resilience (91%). Furthermore, in both cases, it is 2% higher than among individuals who do not live with people at risk. However, the distribution of the frequency of the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses variable is not significantly different depending on living at-risk individual (χ2 = 4.367; p = 0.327).

Figure 7 analyses the vaccination doses among individuals that have suffered the death of someone close to them. It can be seen that all the previous patterns continue to be followed. The vaccination percentages are slightly higher among people who have suffered the death of a loved one compared to those that have not: in low resilience, 96% compared to 94%, in high resilience, 90% compared to 89%. It can also be seen that among individuals who have experienced the death of someone close to them, the vaccination percentage is higher among those with low resilience (96%) compared to those with high resilience (90%). However, the distribution of the frequency of the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses variable is not significantly different depending on having lost a loved one (χ2 = 7.020; p = 0.135).

Figure 8 shows significant differences in vaccination between those who believe that vaccination should be mandatory compared to those that do not. Among those who believe that in no case should the vaccine be mandatory (value 1 in the graph), 77% of those with low resilience and 62% of those with high resilience opted for vaccination (two or more doses). These values are significantly lower than for those who believed that the vaccine should be mandatory (value 5 in the graph), which for both low and high resilience was above 98%. The distribution of the frequency of the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses variable is significantly different depending on the belief about mandatory vaccination (χ2 = 210.582; p = 0.000).

5. Conclusions

The present study has delved into the distribution of sociodemographic variables (gender, age and place of residence), experiential variables during the COVID-19 pandemic (deaths of loved ones, immunological risk status of participants and the people they live with, being a healthcare worker and vaccination beliefs) and the level of resilience. The analysis leads to the conclusion that the distribution of vaccination shows no significant differences in the Spanish population according to the levels of resilience obtained from the participants.

The number of doses of vaccine administered do not follow a pattern associated with greater or lesser resilience or with significantly more unpleasant or traumatic experiences during the pandemic. The vaccination percentage was not significantly affected by any of the following variables: being more resilient, sex, having lost loved ones to COVID-19 or living with or being a person at risk. However, the level of resilience does interact with age, being a healthcare worker and beliefs about vaccines. This study shows that vaccination and resilience were not positively related in the sample distribution, unlike findings on other previously studied variables, such as the use of mask [23].

This study, in the same vein as authors such as [8, 11], has found that the reasons and explanations given to society to get vaccinated are more important than even their sociodemographic characteristics or experiences during the pandemic, even more so in the young population, in which it is easier for the “invulnerability bias” to appear [24]. This research emphasizes the need to raise public opinion and give credibility to the measures implemented by governments and the scientific community. Also, authors such as [8, 11] give importance to the cognitive variables involved in vaccination acceptance. They expose the need to give credibility to the measures implemented by governments and the scientific community. The results of this study coincide with the conclusion of the need to prioritize efforts in this direction. This study demonstrates that to increase vaccination of the population, truthful, credible information is necessary that really affects the beliefs and attitudes of the general population, beyond their personal variables. Vaccination must be promoted with rigorous scientific and awareness campaigns to reach the largest possible niche population. As seen in this research, cognitions and beliefs are essential in vaccination. Vaccination has been a measure that, as observed in this research, is more related to beliefs and attitudes towards the pandemic than to sociodemographic or experiential factors.

Having investigated the use of face masks, social distancing and respecting lockdown guidelines, the relationship between higher levels of resilience and greater acceptance of, and compliance with, these measures was clear. However, with regard to the acceptance of vaccination as a containment measure, this variable was not so closely related to the participants’ scores.

The vaccination doses received by the population are highly related to being a person with a disability and/or dependency and living in cities with more than 5,000 inhabitants.

Regarding sociodemographic and experiential factors, it is worth highlighting the study by Reference [25], which observed that younger people, with barriers to scientific and reliable information, and with attitudes related to low control and helplessness in the face of the virus, were more likely to show doubts about the vaccine. However, in the present study, it was seen that the differences between individuals who were or lived with a person at immunological risk, or who had lost a loved one, were not statistically significant despite the large differences in the percentage observed. That is, sociodemographic factors and personal experiences during the pandemic are differentiating elements in the distribution of vaccination against COVID-19, although not all the variables studied have been significant. However, with the resilience variable, there is greater variability in the results.

Vaccination hesitancy, although a minority phenomenon among most of the world’s population, is therefore related to concerns about the effectiveness and components of the vaccine, as well as possible side effects. In the present study, the belief in the obligation of mass vaccination was a variable related to the greater number of vaccine doses administered. Just as other authors analysed the beliefs about vaccines with a greater probability of getting vaccinated [26].

In conclusion, campaigns to improve vaccination rates should aim to increase the perception that COVID-19 is preventable through vaccination and describe the personal need for vaccination, as well as reduce concerns about vaccination. Although surprising, the low frequency found between the resilience construct and vaccination levels could be explained by the findings of other researchers that we consulted, such as Reference [4]. Personal beliefs regarding vaccination as well as sociodemographic variables and life experiences in the Pandemic were even more related to vaccine acceptance.

Authors such as [15] demonstrated that resilience predicts psychological well-being and protects in critical situations, especially preserving mental health. However, it seems that resilience, and specifically the government measure of mass vaccination of the population, has a relationship that requires the study of more sociodemographic and experiential variables and beliefs about the credibility of vaccination.

To achieve this, it is necessary for governments and the media to improve the transmission of information, providing it with greater credibility and honesty [5]. First, the variables that are involved in the acceptance of vaccines in the world population are to be analysed.

Raising awareness and drawing conclusions in the face of this irreversible pandemic and implementing health prevention programmes in emergency situations of the imminent risk for the world’s population is of the greatest necessity. This, together with the provision of simple, scientific and transparent information by governments and the media, is essential to ensure that the population accepts the health measures proposed in further pandemics, which can undoubtedly occur in the uncertain future.

5.1. Limitations

This research has a series of limitations that need to be considered. On the one hand, it is important to highlight that the information provided from the sample of 1,000 people was obtained through a form for which access to the internet was required. Proper eyesight was also needed to read the questions as an appropriate cognitive status to permit comprehension of the items. This means that, despite the sample having a wide age range, young and middle-aged adults are more widely represented, arguably because of the digital divide.

It is also worth noting that female participation was substantially higher than that of men and those identifying as non-binary. This might be because of the traditional interest of females in issues related to activities involving emotional expression, introspection and communication of feelings and beliefs. It may also simply be due to the fact that, as female researchers, we were more likely to have individuals of the same gender closer to us.

Another limitation of this study is the non-evaluation of psychological variables that are related to compliance with measures. And, this limitation has to become a future line of research.

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the social research ethics committee of the University of Castilla (CEIS), which approved the research with the reference number CEIS643672-J3Q2 and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its lateral amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent

Each and every individual study participant gave written informed consent. Each participant will be sent a copy of the findings upon publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Mar Alcolea-Álvarez contributed to data collection and the development and design of the study. The preparation of the material and data collection were done using the Microsoft Word software package and the statistical program SPSS, as indicated. The first draft of the study was written by the four authors, Mar Alcolea-Álvarez, Natalia Solano-Pinto, Raquel Fernández-Cézar and Cristina Pozo-Bardera. All the authors modified and improved subsequent versions of the manuscript and approved the final article.

Funding

This study was funded by University of Castilla-La Mancha, research group “Health, Education, and Society (Critical Eye)” and co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (grant number 2021-GRIN031088).

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible thanks to the participants who dedicated their time to answering all the questions asked in the research, as well as to the colleagues of the “Critical eyes” research group of the University of Castilla-La Mancha. This group is registered in the Health Research Institute of Castilla La Mancha (IDISCAM).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The online version contains supporting information available at https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1aR3qBidMtbqzyOzzxjcoJB04pL-zgNvH8vcmCUPJVU0/edit?usp=drivesdk&chromeless=1.