Exploring Psychosocial Stressors and Coping Strategies During the COVID-19 Lockdown: A Study of Two Low-Income Communities in South Africa

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced significant challenges worldwide, leading to the reshaping of societal dynamics. These challenges are in the form of psychosocial consequences on community members’ everyday lives. This study aims to explore the psychological factors, particularly psychosocial stressors and coping strategies influencing the two low-income communities during COVID-19 lockdowns. A qualitative community case study design was used through four focus group discussions (n = 28) and 30 semistructured interviews with adults over 18. Qualitative thematic analysis using an inductive approach was employed, to analyse the data. The findings demonstrate that social isolation, confinement, harshly imposed government restrictions and perceived neglect or lack of support from the government led to feelings of entrapment, loss of freedom, frustration and anger among individuals. These emotions, combined with food insecurity, uncertainty and fear of infection or death for oneself or loved ones, contributed to intense psychological stress and heightened levels of anxiety. This environment of uncertainty and fear significantly exacerbated worry and distress. The findings further show that participants displayed both resilience and struggle during these times, using a blend of healthy and unhealthy coping strategies. This sense of resilience was expressed through the communities being more connected in this time of need and people supporting each other where they can. The findings highlighted the importance of religion, spirituality and faith in these stressful times, functioning as a protective coping mechanism against severe psychological stressors. Unhealthy coping mechanisms included substance misuse, violence, social withdrawal and communal divisions, which ultimately deepened social and psychological challenges within communities. Addressing psychosocial stressors and coping strategies is important to prevent long-lasting consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Simultaneously, these insights can inform future strategies to navigate through future potential pandemics.

1. Introduction

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus had led to 1.7 million deaths around the world by the end of 2020 [1]. In South Africa alone, the number of fatalities amounted to 26,521 by the end of the same period [2]. Considering the dire situation created by the virus, evidenced by the number of people infected and lives lost globally and locally, a range of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions were employed. These lockdown restrictions led to the closing of schools and businesses, as well as a ban on all public gatherings [3]. Arguably, the high number of fatalities would have been multiplied were it not for the lockdown restrictions imposed by governments all over the world [3–5]. However, many studies have explored the implications of the pandemic and lockdown restrictions, dissecting their impact on economic and political sectors, as well as their effect on society and individuals [6–9].

The COVID-19 pandemic called for swift adjustments to be made in various aspects of everyday life, including the closing of company offices, shifting to working from home [10] and businesses shutting down due to the strain placed on their activities, resulting in people being retrenched and unemployed ([11, 12], p. 482). Consequently, the COVID-19 pandemic had a further profound impact on society, particularly on livelihoods and the education system. The livelihoods of many were affected by food insecurity, joblessness and further marginalisation, as the poor material conditions of already vulnerable groups increased [13, 14].

Regarding education, over 100 countries experienced the abrupt closure of schools, leaving more than one billion students without access to education facilities [15, 16]. This led to disruptions in learning and limited availability of research facilities. The lack of proper infrastructure, including network and power issues, limited access and poor digital skills, hindered the effectiveness of online education, particularly in developing nations such as South Africa [17]. These challenges underscore the urgent need for educational institutions, educators and learners to embrace technology and enhance their digital skills to align with evolving global trends and the realities of education [17, 18]. In a similar vein, Nejadshafiee et al. [19] also noted that it is vital for the integration of new technologies, namely telenursing, to address and combat medical crises such as COVID-19. Kaviani et al. [20] also noted that disaster management is crucial for nursing students, as they currently lack the competence and preparedness in world conditions such as COVID-19.

These disruptions in learning and the closure of educational institutions led to psychosocial stressors and a lack of support. In a mixed-methods study, Olawale et al. [21] found that the COVID-19 pandemic transformed rural university life, significantly affecting psychosocial well-being. Psychosocial stressors were linked to isolation from peers and colleagues. A further contributing factor was the lack of psychosocial and emotional support systems, which were already under-resourced in rural universities before the pandemic and further intensified during the pandemic. The authors noted that psychosocial stressors further manifest when there is a lack of mediating factors, such as social relation strengthening opportunities, that were provided before the pandemic but had to be placed on hold due to the closure of university campuses [21].

Evidently, Ceylan et al. [8] noted that during COVID-19, government sectors, private corporations and citizens all faced limitations in their resources and capabilities, hampering their ability to cope with the challenges brought about by the pandemic. This is particularly apparent when focussing on psychosocial factors that affected people’s experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychosocial factors refer to facets in an individual’s life that may affect them psychologically and/or socially and could be a combined effect of both psychological understandings and social processes [22, 23]. These facets can characterise how an individual relates to their social context and how these characteristics can impact mental or physical health [22]. For the current paper, psychosocial factors will encompass looking at both experiences of psychosocial stressors and psychosocial coping strategies that were implemented during the COVID-19 period, with particular reference to two local communities within the South African context.

A range of studies also recorded the psychosocial stressors that various groups have experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dubey et al. [24] expressed that the groups most psychosocially impacted are the marginalised groups. During the pandemic, young parents with newborn babies experienced significant impacts, leading to heightened anxieties surrounding their parenting responsibilities and the task of raising children. The unprecedented circumstances caused by the pandemic further exacerbated these concerns, placing additional burdens on these parents [25, 26]. The COVID-19 pandemic also created forms of anxiety and depression for people. For instance, people who feared being infected or infecting other people were anxious about the future, and those who had to quarantine, especially at a new place of residence, experienced loneliness and moderate depression levels [27]. These psychosocial stressors also affected healthcare workers due to both personal and work-related factors that led to emotional distress [28, 29]. Dubey et al. [24] found that frontline healthcare workers faced higher risks of infection and adverse psychological effects, including burnout, anxiety, fear, depression, elevated levels of substance dependence and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Major shifts in society brought on by the lockdown, along with inadequate access to mental health care, raised the risk of mental health problems and added to South Africans’ already high stress levels [30]. South Africa moved swiftly to stop the spread of the virus and put the population under lockdown to preserve the biological health of its citizens [31]. Rwafa-Ponela et al. [32], in a study on two districts in South Africa, found that the pandemic brought fear and intensified anxieties on many fronts, including the financial consequences as a result of all the regulations and slowed economic activity. In a nationwide survey across South Africa by a top pharmaceutical company and mental well-being advocate, the results demonstrated a 56% upsurge in emotional and psychological stress among residents due to the COVID-19 pandemic [33]. A large percentage of the population (52%) had trouble sleeping, intimate partner violence increased by 5%, 49% felt anxious, 48% felt frustrated, 31% experienced depression, 68% were worried about the impact of COVID-19 and 6% considered suicide. In another cross-sectional national South African online survey study, participants reported experiencing stress and anxiety (61.2%), financial-related stress (39.5%) and emotions such as sadness, anger and frustration (31.6%) during COVID-19 [34]. The public’s psychological well-being postpandemic, however, is now a major concern due to increased levels of stress [30]. The study by MyDynamics [33] also reported respondents turning to unhealthy coping behaviours including unhealthy eating habits (81%), alcohol (20%) use, smoking cigarettes (6%), cannabis (6%) and antidepressant or antianxiety medication (22%) [33].

Considering the dire psychosocial impact the pandemic has had on individuals, communities and their surrounding environments, this paper was believed to be best guided by Lewin’s field theory, alongside the health theory of coping as the overall theoretical framework. Lewin’s field theory states that the ‘field’ will be perceived differently by the same person/people depending on the socioenvironmental times that are at play [35]. For example, when looking at the home environment, which is often but not always perceived as a space of safety, refuge, security and familiarity, we observe that during the COVID-19 pandemic, many people viewed their homes as prison-like places of confinement [36]. The value of Lewin’s field theory is found in the notion that the environment influences behaviour modification, which in turn affects how people begin to sociologically process that environment [37]. In addition, according to the likelihood of negative outcomes, the health theory classifies coping mechanisms as either healthy or unhealthy, acknowledging that all coping behaviours are adaptive and may at first lessen distress [38]. Self-soothing, leisure or distraction activities, social support and professional support are all examples of healthy coping mechanisms. However, negative self-talk, hazardous behaviours, social withdrawal and suicidality are unhealthy coping strategies [38]. Within the context of psychosocial stressors brought on by the environment created during the COVID-19 period, there is a need to recognise such stressors and how people cope with these stressors to promote healthier ways of coping. Coping mechanisms refer to the way people interact with problematic situations using problem-focused coping, emotion-focused coping and dysfunctional coping [39].

In exploring the psychological factors, which form part of the psychosocial dynamics explored above, it is worth noting that mental health in South Africa has been placed on the periphery of the health system [40]. Although there has been substantial policy and legislation development in promoting access to mental health services and moving mental health in South Africa towards the centre of the health discussion, Nguse and Wassenaar [40] highlighted that there is an inadequately addressed gap between the policy work and the practical implementation of it all. During the pandemic, just as those who had preexisting physical health conditions were more at risk when it came to the COVID-19 pandemic, Nguse and Wassenaar [40] noted that those who have childhood traumas and other preexisting psychological conditions are also at a high risk of being heavily impacted due to the pandemic. In other words, they are more likely to develop depressive symptoms. Lakhan et al. [41] noted that if mental health conditions continue for extended periods without any proper interventions or treatment, then they are more likely to worsen.

The importance of this study is thus embedded in its ability to aid future protocols and societal tools to help better cope with future pandemics or crises and encourage a more concerted effort to address the psychosocial effects of future pandemics for marginalised and low-income communities (LICs). Although there are existing studies in South Africa on psychosocial stressors, very few, if any, primarily focus on exploring LICs and how they undertook the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the study addresses the gap where there is a lack of studies of a qualitative nature in exploring the lived experiences of communities impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In South Africa, Kim [42] empirically explored the psychosocial stress brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, and they noted that one’s sleep quality is important, in the process of protecting from psychosocial stressors and suicidal ideation. Olawale et al. [21] noted that psychosocial stressors manifest when there is a lack of mediating factors, such as social relation strengthening opportunities, that were provided before the pandemic but had to be placed on hold due to the closure of university campuses. Olawale et al. [21] stated that the psychosocial stressors were those of isolation from peers and colleagues, and the rural universities also lacked sufficient means to provide psychosocial and emotional support, which was further intensified during the pandemic. The university community and interpersonal interactions naturally led to a space where staff and students were better able to cope with the pandemic, but due to the abrupt and uncommon nature enforced by the COVID-19 regulations, the rural universities faced highly increased pressure on psychological and emotional support systems that were already under-resourced pre-COVID-19 [21]. Rwafa-Ponela et al. [32], in a study on two districts in South Africa, found that the pandemic brought fear and intensified anxieties on many fronts, including the financial consequences as a result of all the regulations and slowed economic activity.

This study aims to contribute to the ongoing broader conversation of the effects of COVID-19 in South Africa, particularly on the psychosocial ramifications, and the strategies people in communities used to deal with these during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. The primary aim of this study is to explore the psychosocial factors that impacted people’s experiences of the pandemic, to enhance our understanding of the psychosocial stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic on South Africans and the coping mechanisms they used to manage these stressors.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

The study employed a qualitative community case study design to delve into the nuanced perspectives and experiences of various community stakeholders (including members and leaders) regarding the psychosocial stressors experienced and coping mechanisms used during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, specifically within two LICs. The study questionnaire was designed by a panel of experts in public health, measurement and community research. This paper is part of a larger national COVID-19 mixed-methods study conducted in South Africa [43–45].

2.2. Participants

The two specific communities, one in Cape Town (CT) (in the Helderberg Basin) and one in Johannesburg (JHB) (in Region G), were selected due to their representation of ‘low-income, under-resourced’ areas and the long-standing relationship that exists between the research institute and these communities. The JHB community (Community A) comprises approximately 9000 households, primarily shack dwellings, with a population exceeding 21,000 individuals, including a significant number of foreign nationals [46]. Similarly to other informal settlements and townships in the country, this community faces challenges such as inadequate infrastructure, limited municipal services and amenities, overcrowding and high levels of unemployment.

The CT community (Community B) encompasses a smaller geographical area, housing around 250 houses and twice as many backyard dwellings [47]. Insufficient community infrastructure has resulted in safety concerns, including poor lighting, dilapidated streets and garbage dumps [47]. Presently, approximately 80% of residents are unemployed, with the majority (75%) living just above the poverty line and almost half (47.1%) residing slightly below the poverty line [48]. It is important to note that due to apartheid-era spatial planning, a significant portion of participants from the JHB community identify as ‘black’, whereas those from the CT community identify as ‘coloured’ [49].

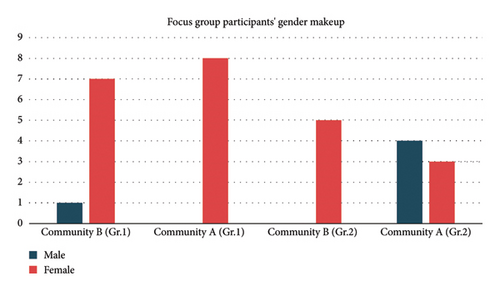

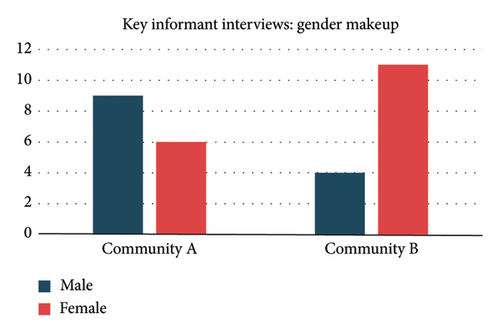

Figures 1 and 2 show the gender distribution of participants for the two qualitative methods (see Figures 1 and 2).

The focus groups conducted in this study are well within the saturation point, as Guest et al. [50] noted that 90% of the themes and key findings were unearthed within three to six focus groups. Within each focus group, the number of participants can range from 3 to 12 [51]. The first focus group discussion (FGD) in Community B (n = 8) and the first FGD in Community A (n = 8) consisted of 16 participants (n = 1 male and n = 17 females). In the subsequent two FGDs, there were five participants in Community B (n = 5 females) and seven participants in Community A (n = 4 males and n = 3 females) (see Figure 1).

In a systematic review conducted by Hennick and Kaiser [52], they found that for studies to reach data saturation, they would need 9–17 interviews. This study consisted of nine males and six females (N = 15) who made up Community A’s interviewees, whereas four males and 11 females (N = 15) made up Community B’s interviewees. As a result, the gender distribution of participants was uneven in both communities (see Figure 2).

2.3. Data Collection

To explore the perspectives and generative responses of various community members and stakeholders regarding the psychosocial stressors experienced and coping strategies employed in two LICs in South Africa, the data collection process included four FGDs and thirty one-on-one semistructured individual telephonic interviews. The study used purposive sampling as the method was particularly suitable for this study as it allowed for the intentional selection of participants with specific knowledge or experience relevant to the research. This approach was further justified by the researchers’ prior and ongoing engagement with the selected communities, as well as the logistical constraints imposed by COVID-19. Key community stakeholders, including members and leaders aged between 18 and 65, were recruited to ensure a diverse and representative sample. These interviews were conducted telephonically due to the COVID-19 regulations.

The FGDs were conducted at the JHB offices of the Institute for Social and Health Sciences (ISHS). Similarly, two FGDs were held in CT, at a central venue in the community that adhered to social distancing guidelines and other COVID-19 health protocols. Due to the nature of the pandemic at the time of the individual interviews (which were conducted before the FGDs), the individual interviews were conducted telephonically. The FGDs, however, were conducted in person but were implemented under strict adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures, such as sanitisation, wearing face masks and maintaining social distancing. Semistructured interview schedules were used to conduct the FGDs and individual interviews to facilitate a meaningful and comprehensive discussion. Before the commencement of data collection, signed informed consent was obtained from participants. Participants were briefed about the aims and objectives of the study and the ethical protocols that guide the research, including voluntary participation, beneficence and nonmaleficence, and they were encouraged to ask any clarifying questions involving their participation. Due to the long-standing relationship of ISHS-UNISA with these communities, a level of trust has already been established. However, it was still important for the interviewer/focus group facilitator to build trust with the participants.

FGDs and interviews were conducted and audiotaped after participants signed informed consent forms and followed all COVID-related health protocols. The interviews ranged in length from 30 to 60 min depending on how much each participant had to share, whereas the FGDs lasted from 45 min to an hour and a half, which was also dependent on the interaction and conversation of all the participants. The main inquiries that guided this study were as follows: (a) how the government’s Lockdown Levels 4 and 5 affected people’s lives; (b) how people perceived the government’s national lockdown; and (c) how people responded to the restrictions and social measures put in place to stop the spread of COVID-19 (see Appendixes A and B).

2.4. Data Analysis

To make sense of the data, qualitative thematic analysis with an inductive methodology was used. The inductive approach refers to how themes are extracted from the raw data of the interviews and the FGDs and are not predetermined [53, 54]. The thematic analysis enabled the researchers to methodically locate, arrange and offer insight into recurring patterns of meaning (themes) in a dataset [55]. As a ‘bottom-up’ approach to data coding and analysis, an inductive approach makes sure that the emerging themes closely match the data’s content [55]. The ability to interpret participants’ shared experiences and the meanings they assign to those experiences is thus made possible by thematic analysis [55].

The researchers independently immersed themselves in the transcripts and extracted relevant themes and subthemes. They then collectively met, compared and discussed these themes. Through this discussion, the most fitting themes and subthemes that were aligned with the aims and objectives of this study were selected. To ensure the credibility of the data, the authors made sure the result accurately represented participants’ experiences of psychosocial stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the psychosocial coping strategies employed to manage these stressors by outlining all the steps in the data analysis process, triangulating the findings from the various FGDs and conducting individual interviews [56].

2.5. Trustworthiness

In the process of ensuring that the study at hand meets the trustworthiness criteria of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability, the credibility of this study is achieved through the authors having their separate analyses of the transcripts, before meeting and combining themes to produce the most accurate themes from the transcripts. This is also ensured through the different rigorous techniques of collecting data, namely FGDs and individual telephonic semistructured interviews. Through these, the transcribed data were triangulated by looking at both datasets and establishing themes and subthemes from them [57, 58]. As such, these themes may be transferable in similar contexts of LICs in developing nations such as South Africa. The in-depth data analysis provided by this study, its transcriptions of interviews and FGDs and question sets for the data collectors ensure rigour in the methods used, making the study a dependable one [57, 58]. Lastly, to ensure the findings are confirmable and are not due to biases, the manner of how the questions were set was such that there were no leading questions and they were open for the participants to express their thoughts [57, 58]. To ensure that very few researchers’ influences or biases were present, the process of researchers analysing the data on their own and meeting to analyse the data collectively helped mitigate the potential researcher biases that could manifest in such qualitative work [57, 58].

2.6. Ethical Considerations

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the University of South Africa College of Human Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee. The specific communities in both CT and JHB were left unnamed due to anonymity extending not just to the participants but the community names themselves. The focus group facilitators and interviewees possessed proficiency in multiple languages, including English, isiZulu, Afrikaans and Sesotho. This language diversity allowed them to effectively communicate and navigate through the various languages spoken by the participants. The group facilitators underwent training in implementing the FGD and interview guides to ensure consistent and standardised data collection. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participating in either FGDs or individual interviews. The consent process ensured that participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks and benefits and provided them with the opportunity to freely and voluntarily decide whether they wanted to participate.

3. Findings and Discussion

This study aimed to obtain an in-depth understanding of the psychosocial factors, particularly stressors, linked to COVID-19 and government restrictions, and the various coping strategies community members in two LICs used to manage these stressors. Aligning with this aim, the findings and discussion are presented under two primary themes, namely (1) psychosocial stressors brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic and (2) ways of coping during the times of the pandemic. The first theme centres on how these two communities coped with the stressors brought about by the pandemic. The second theme presents the various healthy and unhealthy strategies that participants made use of. Each primary theme has numerous subthemes, which explore the larger factors in more nuanced detail (see Figure 3). The participants’ responses are depicted below in various themes and subthemes, and the key informant interviews (KIIs) are displayed for both JHB and CT. Furthermore, the FGDs are also depicted with their reference codes of FGD1 and FGD2, to depict the different FGDs that occurred, accompanied by the participant number. The research team opted to triangulate the two data collection methods, to enhance the research findings.

3.1. Psychosocial Stressors Brought on by the COVID-19 Pandemic

Although governments across the world enforced their COVID-19 mitigation strategies on their respective citizens, South Africans experienced one of the most stringent restrictions globally. As a result, many South Africans in their various communities across South Africa, over time, grew more wary and frustrated at the hard lockdowns that were imposed on the nation. These restrictions, including those that the government enforced, led to various psychosocial stressors for members across the two communities, as explored through the first main theme highlighted above. The consequences of these stressors are further expanded on through the following subthemes: spatial confinements and feelings of entrapment; uncertainty, fear, death and dying; worry manifested; anger and frustrations; and hunger and food insecurity.

3.2. Spatial Confinements and Feelings of Entrapment

‘It felt like for the time being we were prisoners because somebody else is in charge of your life, so it was not cool because you had to do everything that they tell you to do, somebody else has instructed you to do, but you did not want to do’ (KII: 8-CT).

‘During level 4 we still felt “entrapped”. In other words, you still could not go where you wanted to and especially during curfew hours, you had to make a plan to be home at a specific time. It made us feel like prisoners’ (FGD: 1-CT).

‘I do not feel free at all, and I am no longer as free as I used to act, too. I do not laugh as freely, I do not interact as freely, and I am a very open and free person. My openness and friendliness has gone down, and that makes me feel sad. I cannot touch the people I love. I no longer feel as cheerful as I used to feel. And when I cannot go to the soup kitchen on a specific day, it really affects me mentally. I really struggle to deal with that’ (KII: 4-CT).

KII 4 expresses that the limitations of their freedoms have led to a reduction in their sense of self. This suggests that during these times of lockdown, they began to lose parts of themselves, thus expressing examples of the great psychosocial strain this pandemic had on the two communities. During the hard Lockdown Levels 4–5, the government deployed more police and traffic officers to monitor people’s movements and restrict unauthorised movement in the cities (i.e., travel permits). Thus, the participants mentioned above felt like prisoners/criminals who had been locked up in their own homes. The term ‘lockdown’ itself has its widespread use in the correctional services world and speaks to the control of prisoners. Although the introduction of preventative measures such as the lockdown was not intended to be used in the same contextual way as used by prisons (i.e., for punishment), the unintended consequence of these lockdown policies, as expressed by the participants, became more of a punishment [64–66]. The interviews and FGDs explored these changes, which removed one’s usual routine, drastically reduced social contact and limited access to goods and services all culminating in frustrations, anxiety, depression and feelings of isolation for the participants. These mark the high increase in the psychological symptoms of distress due to the pandemic. In a study conducted in Korea by Lee and Park [67], on the feelings of entrapment, they noted that it led to decreased mental health, as well as well-being. In alignment with this paper’s findings, both speak on how detrimental confinements and feelings of entrapment can be due to the COVID-19 lockdown regulations.

3.2.1. Uncertainty, Fear, Death and Dying

‘When you receive a call, and they tell you that someone you know has passed on due to COVID-19 illnesses, and then you start asking yourself if I am next [in] line of people passing away. That was one of the stressors that we experienced a lot’ (FGD: 1-JHB).

‘The infection rate was very high. It was constantly on the news, and that spread so much fear. And this puts so much stress and pressure on a lot of people’ (KII: 2-CT).

A participant stated how they feared the swooping death wave of the virus. They were left pondering questions like ‘Am I next?’ This, admittedly, has caused them a great deal of stress and concern, not just for the lives of friends and families that are not immediately close by, but more so about their sense of mortality. The fear went beyond the individual fear of not surviving the pandemic, but it also transferred to the fear and worry of losing loved ones: ‘My fear was losing my family to Covid’, as well as leaving loved ones behind if one were to pass away from the COVID-19 virus: ‘My biggest fear was if I die from COVID-19’ (FGD: 1-CT) and ‘…who will look after my children since I am a single parent’ (FGD: 1-CT). Being uncertain about the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a ‘pandemic fear’ that has become arduous for the two communities [69]. Lee and Park [67] further emphasised that the COVID-19 lockdown regulations led to an increased sense of uncertainty, whereas Rwafa-Ponela et al. [32] observed that it brought fear and distress to individuals. The abovementioned studies further support the findings of the current paper.

3.2.2. Worry Manifested

‘I am extremely stressed and scared. I do not know for sure anymore, what is going to happen to me and to my life. I am paranoid. And worried about all those people I see. It is scary. I am so scared. […] I am also very worried for my family, so I do not want to put them in danger by going to see them. I avoid visiting people unnecessarily, and I think that it is important to stay at home, unless it is absolutely necessary to go out’ (KII: 2-CT).

‘I am very worried about being infected. I do a lot of work around the community; I am a community worker […] I only visit families in accordance with the mandate of my work. […] I am extremely worried; I am so very worried. I am worried for my family. I am worried about the preservation of life’ (KII: 3-CT).

Alongside their fears and uncertainties, several worries were also made manifest. These include worrying about being infected, worrying about infecting their families and worrying about the well-being of their community. To some degree, this level of worry expressed by participants also led to paranoia, representing the extreme effects of worrying. Paranoia refers to a phenomenon that has been observed in other studies, where the pandemic paranoia has led to paranoia-like beliefs about the pandemic [72, 73]. The intensified worry noted in this study forms part of the Kowalski et al. [72] and So et al. [73] notion of pandemic paranoia. Paranoia is typically seen through the lens of psychosis, and Raihani and Bell [74] emphasised that it can also be seen in the public and manifests itself as a social cognition that displays perceived persecutors, being involved in some conspiracy against public individuals. Raihani and Bell [74] highlight that although this particular social cognition is categorised as one of the pathological markers of a mental health disorder, it is pertinent to be mindful that it also occurs in the normal individual, being part of their everyday lived experiences, depending on the conditions. Furthermore, how participants dealt with their worries is further elaborated on under the healthy and unhealthy coping mechanism themes. The results above demonstrate a feeling that plagued communities as this was a time of many unknowns. Although scientific and accurate information was becoming more and more accessible, the other side also kept a steady flow. The worry manifested even though people were aware of how the virus spread, and the sense of worry remained, especially when they navigated and interacted with family and communal spaces. During this time, people experienced many emotions in varying degrees, some of these being anger and frustration.

3.2.3. Anger and Frustrations

‘We had a “mistrust” feeling–didn’t allow anybody into the house or hug anybody like in the past which also caused frustration’ (FGD: 1-CT).

‘People got frustrated and the gender-based violence rate was much higher’ (FGD: 1-CT).

‘The reason behind why now they no longer wanted to adhere to the restrictions is because they’ve been in their houses for a very long time, and they were frustrated including myself we were very frustrated’ (FGD: 2-JHB).

‘There seemed to be a lot of anger in the community, a lot [of] confusion; the people did not understand, and they felt like you were just being annoying–or like you were bothering them whenever you would ask them to wear a mask and to sanitise’ (KII: 2-CT).

These expressions ranged from an individual level to a familial level and expanded further to a communal level. Individuals did not want to let community members in their homes due to the uncertainty of who may be infected and who may not. As such, there was a ‘mistrust’ among community members. Furthermore, being in lockdown led families to see sides of their family members that they rarely if ever saw; for instance, a participant expressed that his children ‘don’t know how their father behaves when he is angry [or] when he is happy’ (FGD: 2-JHB); as such, the lockdown was an opportunity for families to connect more and deal with each other’s emotional and psychological states of being, often presenting as a challenge on its own in some cases.

In the larger sense, the community was frustrated and angry at the government for the neglect and the harsh policing of their movements. As such, community members would rebel by not using masks or obeying other COVID-19 regulations and practices; community members no longer wanted to be entrapped in their own homes and began reclaiming their autonomy. What tended to brew out of the fear, uncertainty and worry was a mistrust of other community members, not knowing who may be infected or not [75, 76]. The pandemic and lockdown restrictions thus gave way to a range of emotions, which affected not only the individual feeling the emotions but also the connection among community members, further impacting the anger and frustration that were felt during this time. Kubacka et al. [77] referred to this anger and frustration as pandemic rage, where individuals express feelings of both anger and frustration due to feelings of helplessness. Being able to help others in this time of need, whether it is one’s family or other community members, was vital for the community members and greatly contributed to them coping better during the pandemic. The level of help one could offer during this time was limited, along with everything else, including access to food, which led to increased food insecurities in the communities.

3.2.4. Hunger and Food Insecurity

‘One of the most traumatising things that the community experienced was the fact that parents had given up on trying. They would go days without food, and they had to watch their children starve. They were forced to accept the fact that their children might die before them. One of the men that everyone knew lost his job. His wife also lost his job. Their children were starving and not getting enough to eat from the soup kitchens, because there is never enough and growing children need nutrients. This man walked out on his family…The situation was so bad that he had decided that he could no longer watch his children starving; he would rather abandon his family than go through that’ (KII: 4-CT).

‘The biggest stress that my community experienced was the starvation. I have neighbours who have infants, and they are starving. It is so tragic and so painful to see. I cry a lot, because of all of this’ (KII: 3-CT).

KII 3 stated that their community’s major concern was the issue of necessities, specifically food. People went hungry when they could not go to work and provide for their families, and this survival stressor brought many more physical, psychological and social stressors to the community. The participant’s account tells the story of a father who ‘walked out on his family’ due to there not being enough food to feed the family. This pressure to provide demonstrates the level of struggle and crippling strain the pandemic placed on families to the point where ‘parents had given up on trying’.

Evidently, one of the biggest psychosocial stressors that affected most community members was financial issues. Those who had some savings began to suffer as the lockdown stages kept being extended. Some could not afford to purchase their essentials due to dire financial conditions resulting from the economic halt. Those who were most affected by this abrupt introduction of change were those who had no prior savings but were living from pay cheque to pay cheque. Understandably so, the majority of South Africans live below the poverty line, and thus, saving for times like the pandemic does not become feasible [79]. Even though the government had set aside a social relief fund, this fund did not have the intended reach that was proposed to the public [80], which ultimately affected people’s ability to provide for their families due to financial constraints during this time, leading to food insecurity and hunger.

Hunger extended leads to ‘starvation’. Both informants highlight that this issue of food security was the most impactful stressor in their communities, whereby families could be crippled and broken apart by the effects of the pandemic, not knowing if they would recover [81, 82], indicating the dire need for community food relief efforts during times of crisis. A study conducted in India on food security found that although there were measures put in place by the government through the provision of money and food support, there were still some gaps in ensuring that hunger is not an issue during times of crisis [83]. One of these gaps can be noted in this current study under factors of corruption in South Africa, where food parcels were used as part of political agendas. In other words, political parties prioritise their party members over going with who needs the food parcels the most. These instances of having shortages of food in the communities made the communities even more vulnerable.

3.2.5. Vulnerabilities in LICs

‘We learnt that life is not about myself, we learnt that everyone is vulnerable’ (FGD: 1-JHB).

‘There was no sufficient support as my colleague mentioned that the elders were ordered to stay indoors without any support, especially for the unemployed, the sick, the disabled, those are the most vulnerable people in our communities, there was insufficient support from the government’ (FGD: 2-JHB).

‘The drug problem in my area meant that many addicts are extremely vulnerable’ (KII: 5-CT).

Participants in the focus group expressed their views on their overall experience from the pandemic, and one stated that they recognised and ‘learnt that everyone is vulnerable’. This realisation allowed the participants to not dwell on only their problems but to step outside of themselves and empathetically note that they were not alone in the struggles of the pandemic. Another participant expressed that there were certain community members (‘elders, […] the unemployed, the sick, [and] the disabled’) who needed support from the government and help, but never received it, which increased their vulnerability. If the socioeconomically vulnerable groups in these communities received sufficient help from municipalities, and government overall, their harsh COVID-19 experiences would have been reduced [86].

‘There is a gang that hides inside abandoned houses in our area–we refer to them as the skollies, I do not know the English word for that. They are young people, some of them high school children. They sell drugs. They hide in the houses, stab people, and rob them of their things in order to sell those things. They walk around with guns. It is extremely unsafe. The police know about all these aggravated robberies and shootings at the hands of these gangs, but they do not come out. They know, even, the people involved. Everyone is afraid for their lives’ (KII: 2-CT).

This informant noted that the climate that the pandemic has exacerbated in these communities has placed many at risk and exposed to criminal activities through victimhood, and perpetration, as school-going children ‘…sell drugs […] hide in the houses, stab people, […]rob them of their things in order to sell those things, [and] they walk around with guns’. Thus, ‘[learning] that everyone is vulnerable’.

The role of the police force is a dire one that reflects neglect and a lack of interest in addressing the issues in these communities during these times (also see Alcohol, stress and violence). The participant expressed that ‘The police know about all these aggravated robberies and shootings at the hands of these gangs, but they do not come out. They know, even, the people involved’. This suggests that there is fear from the side of the police force and the community members to address the issues of violence, shootings and robberies. This inaction from these stakeholders adds a further vulnerability that places additional psychosocial and biological negative pressure on the community members, thus leaving ‘everyone afraid for their lives’.

These aforementioned factors that made the people of these communities’ lives difficult can largely be attributed to corrupt practices, in various sectors, where funds were meant to be adequately allocated to help the unemployed, by providing grants, to keep small businesses and farms afloat, helping hospitals with healthcare equipment (i.e., medical oxygen), and providing food parcels to feed the hungry [91, 92]. Santana et al. [85], in a study in Sao Paulo City, Brazil, noted that these vulnerabilities were brought about by the poor socioeconomic conditions facing many LICs, and as such, they led to psychological distress. In this study, 85% of the participants indicated that they were experiencing psychological distress, and 40% indicated that they were food insecure (moderate to severe) [85]. This quantitative study sheds light on the global extent to which LICs have been affected by the pandemic and supports the current study’s findings on communal vulnerabilities. Sanchez et al. [93] further discovered that the pandemic has led to an increase in violence against women and children.

These vulnerabilities can further be linked to increased anger and frustration not just with the regulations and lockdown policies but with the government not providing adequate support for the communities. Being vulnerable makes people worry more about everything in their lives and the communities surrounding them. To mitigate this, community members developed ways of coping with the pandemic and these ways are explored in the following theme.

3.3. Ways of Coping During the Times of the Pandemic

During the times and trials of the pandemic experienced globally, South Africa was not exempt. Third-world countries such as South Africa were hit the hardest and were still struggling to recover parts of their economy that were lost [94, 95]. During COVID-19, however, the South African government seemingly did not do the job it had pledged to do. People were thus left destitute and on the brink of survival, having to find ways to navigate and survive their reality. This theme entails an exploration of some of the negative and healthy ways of how the two communities coped during the COVID-19 pandemic. This section will explore the different ways communities coped during the pandemic. These ways of coping are both negative/unhealthy and positive/healthy. In each unhealthy or healthy way of coping, there are subthemes explored dissecting the nuances of how community members coped or struggled. The first of these ways of coping are the negative techniques, which are subthemed by (a) alcohol, stress and violence and (b) communal divide and social withdrawal. Following this subtheme are the healthy coping techniques of community members where they used (c) religion, spirituality and faith, as well as (d) community connectedness and social support.

3.4. Negative/Unhealthy Coping Techniques

This state of extreme stress, not only on an economic and financial scale but also on a psychosocial scale, heavily affected people. These psychosocial stressors brought about by the pandemic resulted in many people coping in an unhealthy manner. Here, we define unhealthy coping mechanisms as those that do more harm to an individual and the community, in both the short and long terms. These unhealthy coping techniques, specifically alcohol, stress, violence and communal divide and social withdrawal, will now be explored.

3.4.1. Alcohol, Stress and Violence

‘…I was thinking about those who drink like homeless, underprivileged people, people who use alcohol because of the things they were going through. They could not choose but at the end of the day they wanted something to use to get through the stress and that created problems… [People were] making their own drinks, people even using like sanitiser making their own beer and a lot of people got sick from the community’ (KII: 9-CT).

‘People were frustrated and stressed, they needed to smoke, and others were drinking alcohol because of the stress, but it was so expensive people would take their last money to buy these because of the stress’ (FGD: 2-JHB).

KII 9 notes that many people before the pandemic depended on recreational drugs and alcohol to ease their daily stressors in life. During this time of intense psychological stress, there was a lack of outlets for people to deal with this stress. This has further added to the struggles of coping with the pandemic.

The yearning to deal with one’s stressors using alcohol and drugs has led to some community members resorting to making their own brews using ‘sanitisers’, where ‘a lot of people got sick [in] the community’. Alcohol poisoning can lead to hospitalisation and in some cases death [97]. Furthermore, there were community members who resorted to ‘take[ing] their last money to buy these because of the stress’. The purchasing of these expensive alcoholic beverages and beverages exacerbated the state of hunger and starvation in the communities, as in some households, the money that could have been used to buy some groceries went to buying alcohol to cope with the stressors in their lives. These findings are corroborated by a study conducted in Brazil on alcohol and cigarette consumption during the pandemic. Schäfer et al. [98] noted that cigarette and alcohol use were more prevalent among people who reported feeling down, depressed or stressed out.

One of the factors that could have led to such social withdrawal is those indicated by Participant 5, the ‘frustrations’ and the desire to gain access to alcohol and drugs, as these were many community members’ previous coping mechanisms before lockdown. Participant 5 also highlighted the current state of communities, especially impoverished ones, whereby there is a huge dependency on drugs and alcohol [98].

The ban on alcohol and cigarette sales had further implications for some community members as they were now not able to use their alcohol as a coping mechanism to deal with stressors, which resulted in them struggling [99, 100].

As a smoker and someone who drinks alcohol, it was very difficult to cope [ ]

‘When the law enforcement came, they would beat us, make us roll on the ground and pour us with water as if you are doing something wrong when you were only making small gatherings’ (KII: 4-JHB).

‘There was also an extremely high level of domestic violence because men could not access their alcohol. They would beat their wives and abuse their children. It was terrifying. So many women and children suffered. […] The police did nothing to stop them. They did not care, and they did nothing about the violence, the shootings and stabbings over drugs’ (KII: 5-CT).

The stressors, anxieties and frustrations that came with the lockdown and all its uncertainties led to a lot of violence in the two communities, in particular domestic violence. Key Informant 5 stated, ‘There was also an extremely high level of domestic violence because men could not access their alcohol’. Some of the men in the communities ended up taking out their frustrations on their families as ‘They would beat their wives and abuse their children’, thus causing ‘So many women and children [suffer]’ more than the pandemic and other associated stressors. What became more concerning when it came to the violence associated with alcohol and drug use was how the police in these communities acted and addressed matters. Key Informant 4 states that ‘law enforcement came, [and] they would beat us, make us roll on the ground and pour us with water as if you are doing something wrong when you were only making small gatherings’. Officers had abused and assaulted them, even though they were not breaking the regulation rules for public gatherings. Gunawan et al. [101] and Yesufu [102] refer to this behaviour as ‘police brutality’, which is the infliction of mental and emotional suffering through unlawful violence and intimidation, which exceeds legally sanctioned police practices, including unjustified severe beatings.

This lack of trust and frustration towards police officers and other law enforcement bodies was noted by the participant, who stated, ‘The police did nothing to stop [the men who abuse their wives and children]. They did not care, and they did nothing about the violence, the shootings and stabbings over drugs’. These participants highlight the neglect that police and law enforcement officers had towards the communities. Thus, the violence that they ought to have stopped became the violence they encouraged, whether directly or indirectly, further exacerbating the nature of police brutality and the lack of trust towards police officers [101, 102].

Literature shows that these bans resulted in reduced accidents and acts of violence [103, 104]. However, this study demonstrates that violence is not automatically solved through banning alone, but that there is a systematic approach that ought to be implemented, for instance, easily accessible and affordable psychological services to aid in addressing the deeper underlying issues in the two communities. Another layer in addressing the matter of violence is to improve governmental services, such as police services, to address criminal acts swiftly.

3.4.2. Communal Divide and Social Withdrawal

‘There was a stigma around COVID-19 people who had tested positive were not accepted as normal people. There was a lack of education around COVID-19. We tried to educate our community members about the virus because we saw that it was creating division within our community’ (KII: 7-CT).

‘I kept it to myself’ (FGD: 1-JHB).

These informants note the divide that the fear of being infected and in some cases passing away had created. A participant noted that there were members of the community who had been infected and subsequently ostracised by their community in many ways. For instance, those infected community members are viewed as ‘abnormal’ people. This ‘stigma’, according to KII 7, is due to the lack of accurate knowledge and education about the virus in their communities. Similar trends of how this ‘stigma’ has manifested throughout history can be seen in the advent of the HIV/AIDS epidemic [105]. In a systematic review of HIV studies conducted in South Africa, looking at the stigma and its associations with depressive symptoms, the author [106] noted that there was a strong association between depressive symptoms and internalised stigma, thus indicating that those who are infected, or suspected to be, are more likely to experience more severe psychological stressors, than other members in the two communities.

Some participants, beyond the COVID-19 restrictions, have resorted to ‘[keeping to] themselves’. This suggests that participants have refrained from social interactions even in times of lenient lockdown policies practices (i.e., Levels 1–2) and low infection rates. This indicates that participants have been engaged in an unhealthy coping technique that limits their social engagement, further increasing the sense of isolation, anxiety and other psychologically related symptoms experienced by participants during these difficult times. They did not seek a social support group like some of the other participants, but rather, they ‘kept to themselves’. According to Stallman’s health theory of coping, this is seen as an unhealthy form of social engagement, or lack thereof, called social withdrawal [38].

This subtheme demonstrates that no matter how much information people may have access to, a sense of stigma may still linger. As a result, whether people have the correct information about the COVID-19 pandemic or not, there remains a certain factor where, at times, stigma can trump logic. How one navigates the pandemic seems to also somewhat be linked to psychosocial mechanisms and protective factors. In other words, although not conclusive, one may cope better with fewer psychosocial stressors hindering their navigation through the pandemic and having more protective and healthy techniques to use during this difficult time for the world.

3.5. Positive/Healthy Coping Techniques

‘I go to church, and I go to the gym, I do all the stress management activities because I am scared of using the chemicals like going to the doctor or hospital, so I resort to natural remedies to manage my stress level’ (FGD: 2-JHB).

‘Being supportive to one another, we learnt that life is not about myself, we learnt that everyone is vulnerable, we learnt that anything can happen to anyone, we learnt that rich or poor we can be equally affected, we learnt that it does not matter where you stay you can still be affected, we learnt that it’s not about Europe, America or South Africa or Africa or any other country, we can all be affected. Those are some of the lessons that we learnt’ (FGD: 1-JHB).

‘As school goers we were only encouraging each other to study since we were not able to finish the syllabus at school, we were only attending a few days. We encouraged each other that every day we must try and do something because sometimes some teachers were absent’ (FGD: 1-JHB).

These participants expressed how they managed to mitigate the psychosocial stressors brought on by the pandemic. Participants stated how they used the gym and church as strategies to avoid going down the unhealthy path of coping with psychosocial stressors. Their routinised strategy was a more sustainable means of coping than that of those who resorted to unhealthy ways of coping. The use of coping mechanisms, such as engaging in physical exercise, aligns with the health theory of coping. This theory suggests that incorporating activities such as exercise into one’s coping strategies is an effective approach to promoting overall well-being and resilience [38].

Participants highlighted the importance of social support as a coping mechanism and the understanding that ‘everyone is vulnerable’. In their reflections, participants expressed that one of the key components of their social support was ‘encourage[ing] each other’ to do their schoolwork and not fall behind and succumb to all the stressors affecting their families and their communities. Forming social groups has proven to be beneficial in curbing the anxieties and depression associated with being in isolation [107].

3.5.1. Religion, Spirituality and Faith

‘We were praying’ (FGD: 1-JHB).

‘My coping mechanism was praying, both by myself and with my family. My faith helped me deal with a lot of the stress’ (FGD: 2-JHB).

‘I do not know how I coped; I made the best of each day as it comes with the family. I would lock myself up just to get my time alone praying or reading books, I would see my family when I felt I was in a state to be with them again’ (KII: 10-JHB).

Participants indicated that one of their main coping strategies was ‘prayer’, whereby they connected with God and sought solace and refuge, and they were also easing off their psychosocial burdens onto God to carry. According to the health theory of coping, these participants made use of the component of self-talk, through their prayers and faith [38]. Religious affiliations, even though they were all closed, provided solid grounds for not only a healthy form of self-talk but also set grounds for social support provided by other church members.

The benefits of social support are seen as incredible coping strategies, especially when we are social beings by nature [108]. Thus, it is worth noting that clinical depression and human social isolation are related [109]. During this time, most people were not allowed to socialise much with their friends and families. This caused a rift in the psychosocial fabric of the communities. Some of the participants in this study made ways to maintain these social bonds and actively created more social support structures to get through the COVID-19 pandemic.

In their reflections, KII 10 states that although coping with the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdowns was difficult, she noted how she made productive use of the mandated confinement. She would ‘lock [herself] up just to get […] time alone praying or reading books, [she would then see her] family when [she] felt [like she] was in a state to be with them again’. This spatial confinement (see Theme 1) resulted in her doing some introspective work through prayer and reading, and she would then interact with her family only when she felt that she was psychologically, spiritually and emotionally fit to do so. Coping strategies such as these may contribute to reduced levels of violence, as communities and families would be in a better state to connect with families and the community. In this study, religious coping was thus a vital part of coping well during the COVID-19 pandemic [110]. Zhang et al. [111] noted that although participants in their study referred to a religious and spiritual dynamic as a coping strategy, they also expressed how it led to religious/spiritual struggles such as existential doubts. Here, it is worth noting that although one form of coping can be instrumental in one’s overall well-being, on its own it does not hold off the stress of the pandemic, as it may still creep in via that same coping mechanism. As such, it was illuminating that participants expressed multiple ways of coping, and using these interchangeably seemed to be the best strategy. One of these was how the communities remained connected and continued to provide support for each other in the community.

3.5.2. Community Connectedness and Social Support

‘There was no difference in belief that separated us. It did not matter if you were Islam, Christian, or Hindu–everyone worked as one. We were united. We prayed together daily before we opened the kitchen to the public. There was respect for one another. The food was Halal, so that everyone could eat. From this experience, each of us realised that we are greater than our individual selves. We are all human’ (KII: 4-JHB).

‘That people were feeding one another from their own houses. People were looking after one another’s well-being. The virus, in a way, brought the community closer together’ (KII: 2-CT).

‘There was a lot of violence that was reported in families around my community due to stress and anxiety that came with the lockdown, we had to attend to these families and assist where I could’ (KII: 8-JHB).

KII 4 states how the pandemic has made their community’s religious organisations work closely together and how mutual respect among community members leads to the recognition of each member’s humanity beyond other factors, such as religion. This coming together of the community was further expressed by KII 2, who states that ‘The virus, in a way, [had] brought the community closer together’. The social support that community members displayed during the pandemic depicts a healthy coping strategy for the individuals in the community. This communal support is akin to the South African philosophical expression of Ubuntu, which states ‘I am, because you are’, which speaks to the collective social responsibility [112]. Ubuntu is also in practice through KII 8’s statement, where they had to help in whichever way they could to address the issues of violence brought about by the ‘stress and anxiety that came with the lockdown’. This united sense of community beyond religious coping has far-reaching effects in addressing the communities’ concerns, for example, food insecurity. The dynamic of community unity is vital for the psychological bonding of the two communities, especially in addressing the social threat of the COVID-19 pandemic [113]. Borkowska and Laurence [114] noted that social cohesion during the pandemic was placed under immense strain; as such, the overall levels of social cohesion were lower during June 2020, compared with other pre-COVID-19 times. The current study noted this phenomenon in one of the previous themes but also notes here that throughout all the psychosocial stress brought on as a result of the pandemic, communities still found ways to connect with and support each other.

Difficult times both separate and bring the communities closer together than before. Both phenomena can be true for a single community, and there could be periods of strong connections and periods of turmoil. How communities navigate is inextricably linked to their pre-COVID-19 conditions. In other words, if a community struggles with food access, then such matters can often be exacerbated during the pandemic. It has become apparent in this study that communities were told to focus on lockdown regulation implementations and not how these conditions affected their psychosocial well-being. Thus, a much-needed effort to address the psychosocial conditions that affect communities is vital.

4. Conclusion

This study aimed to enhance our understanding of the psychosocial stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic as experienced by two communities in South Africa and the coping mechanisms they have used to manage these stressors. The themes and subthemes explored the vast effects of the pandemic on the public, especially focussing on the two communities under study. Through this exploration, it became evident that many areas need to be addressed by all sectors of society, from the government and big corporations to the health sector and the education sector. The issues experienced by these participants, whether directly or by observation of the happenings in their communities, tell a story that has been occurring before the pandemic, a story of domestic and child abuse, criminal activities, joblessness, substance use and abuse and food insecurity.

A stark realisation is that given all the stressors, none of the key informants have mentioned that they had sought out formal psychological guidance/help during this period in the country. It could be argued that, according to Maslow’s hierarchy, and in line with what the theory states, psychological concerns are not the priority when the basic survival needs have not been adequately met [115]. Dire as it may be, it is worth pondering how things would be if these stressors were to go unaddressed. Granted, the COVID-19 restrictions have come to an end, but their ramifications are still felt and experienced by many, for instance, the large unemployment rates, poor government services and weak economic performance. If these issues go unaddressed, then it is likely that there will be intense civil unrest (i.e., July civil unrest and looting), and the haves will be targeted by the have-nots and the barely surviving [116–118].

4.1. Limitations

Although COVID-19 was a global phenomenon, this study’s interpretations and applications are unique to the two communities that were under study and thus do not represent all townships or informal settlements. Each township and/or informal settlement may have their unique experiences; however, it should be noted that some aspects explored in this study may be useful for challenges experienced in similar contexts. The study did not explicitly measure psychological distress using psychometric scales or other measures, to determine other psychological conditions other than those self-reported.

4.2. Suggestions and Recommendations

Although the psychosocial stressors and coping behaviours that this study has explored have been assessed through the COVID-19 lens, it is important to note that such psychosocial stressors and coping strategies may be displayed during other stressful and nonpandemic times. Therefore, there is a need for future studies to be done in vulnerable communities beyond the COVID-19 conditions, to address issues increasing their psychosocial stressors. There is also a need for interventions such as psychoeducation, psychologists, social workers and registered counsellors in under-resourced communities to help address the psychosocial challenges experienced. It is recommended that other interventions be implemented beyond those addressing psychosocial needs, as it has been evident in the study that these stressors are a result of other social factors. Thus, it is important to ensure food security and safety throughout these communities to drastically reduce these stressors and, consequently, mental health concerns. Future studies need to look at food security in vulnerable communities such as townships and/or informal settlements. Beyond food security concerns, there is a dire need to address the issue of drug use, violence and alcohol consumption. There is also a need for future studies to introduce healthier ways of dealing with life’s difficulties and challenges, rather than resorting to drugs and alcohol. Although these issues experienced by these communities are not to be resolved through psychology alone, they rather require a multisectoral intervention through governmental intervention, NPOs and municipalities addressing the ills of these communities to create environments that allow people to thrive and not struggle to survive. Lastly, there is a need for future studies to have a concerted effort to postpandemic/post-COVID-19 interventions focussing on long-term trauma, looking at a loss of financial security, as well as loved ones.

In a country where 50%–60% of its workforce comes from small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and has had their daily operations temporarily or permanently affected. The lockdown periods placed a heavy strain on many SME sectors, leaving countless workers affected. Thus, the importance of reviving, and strengthening SMEs post-COVID-19, is key [119].

Disclosure

This paper was presented at the 27th Annual Psychology Congress hosted by the Psychological Society of South Africa (PsySSA) in October 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Appendix A: FGD Questions

- 1.

This pandemic affected all of us. We want to find out how did it affect you and how did you feel, especially during the hard lockdown periods. How did you deal with it and what did you do during this period?

- 2.

If you think back to the Level 5 lockdown period, what was your feeling? Was it more positive or more negative?

- 3.

Are there any other people that you know of who lost their jobs during lockdown and how did it make you feel?

- 4.

How did it make you feel when people lost their jobs or had less income during lockdown? And how do you feel about the people who assisted these people with food?

- 5.

How did it make you feel when the president or ministers implemented the strict rules during lockdown?

- 6.

Did any of you lose any close family members due to COVID-19?

- 7.

Where do you get the strength to carry on and support the community after losing so many family members?

- 8.

Would you say that the people in your community adhered to the government’s regulations that were set during lockdown?

- 9.

Have you been vaccinated? And what would be the reason for vaccinating or not vaccinating?

- 10.

You referred to ‘lessons’ that you learnt during the lockdown period; could you explain in more detail?

- 11.

How did the fake news on social media about vaccines make you feel?

Appendix B: Interview Questions With Key Informants

- 1.

What are your experiences of the restrictions imposed by the government during Lockdown Levels 4 and 5? (Probe: experiences of occupational loss; social and recreational restrictions).

- 2.

What are your perceptions of the national lockdown imposed by the government?

- 3.

Did people in your community adhere to the social measures and government restrictions to curb the spread of COVID-19? Yes/No. If yes/no, why/why not? (Probe: What are the factors that prevented people in your community from adhering to the restrictions?)

- 4.

What are the kinds of experiences of support that you or your family members received from others during lockdown? (Probe: family, community, state, UNISA, others)

- 5.

What are the kinds of experiences of support that you or your family members provided to others in your community or elsewhere?

- 6.

What kinds of stressors have you or your household experienced during the lockdown? Did any of these stressors lead to violence or injury in your home or community?

- 7.

How did you cope with the lockdown measures?

- 8.

What are the lessons you have learnt from this lockdown?

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.