In the Third Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic, the Worry of Applying to the Prosthodontics Clinic or Transmitting COVID-19 to Relatives Can Cause Anxiety/Depression and Not Being Able to Wear a Mask During Treatment Can Also Cause Anxiety

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the anxiety and depression levels and the factors affecting them in the patients who applied to the Prosthodontics Clinic during the end of the pandemic process with the ‘Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)’.

Methods: To determine the symptoms of anxiety and depression, probable cause questions and the “Turkish version of the HADS” were applied to the volunteers who applied to the Prosthodontics Clinic. In the study, independent groups t- and one-way ANOVA tests were used to compare the data according to the groups, the Chi-square test was used for the relationships between group variables, and logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors affecting anxiety and depression.

Results: A total of 194 volunteers (96 male, 98 female) were included in the study. Of the participants, anxiety was detected in 42.3%, depression was detected in 58.8%, and the HADS average was measured as 15.97 ± 7.66. In the depression score classification, the difference between the depression scores of nonsmoking participants (7.8 ± 4.03) and smokers (9.07 ± 3.36) was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.036). Applying to the prosthodontics clinic during the period when pandemic measures were reduced (OR = 2.158) and the possibility of transmitting COVID-19 to relatives (OR = 1.816), and removing the mask during examination and treatment (OR = 2.245) were factors that increased the risk of anxiety. Applying to the prosthodontics clinic (OR = 2.757), the possibility of transmitting COVID-19 to relatives (OR = 1.653) were factors that increased the risk of depression in participants.

Conclusion: In the third year of the pandemic, we can assume that patients who have not had COVID-19 and were smokers who applied to the prosthodontics clinic are more prone to depression. Also, it can be said that application to the prosthodontics clinic during this period and the worrying about transmitting COVID-19 to relatives are both anxiety and depression-increasing factors. Removing the mask during examination and treatment is an anxiety-increasing factor.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 pneumonia can cause respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and mortality. The strict isolation decisions taken at the beginning of the pandemic in the world and in our country (the community should stay indoors as much as possible, use masks, and follow the distance rule of at least 1.5 m, etc.) have gradually been relaxed due to the availability of the vaccine and the better prognosis of the new variants. However, to prevent transmission, the rules on masks and distance are still in force for people receiving care in health facilities, which are still considered risk areas. However, in the case of dental treatment, the 1.5 m distance between the patient and the dentist, which is considered safe, cannot be applied because the treatment area is the mouth. This situation, which increases the risk of transmission, has led to patient anxiety, treatment postponement, no treatment, or disruption of treatment protocols in the first year of the pandemic. Due to the widespread transmission of COVID-19 and the characteristics of the dental examination environment, dental health workers and patients were at risk of cross-infection [1]. This situation can occur as COVID-19 infection among dental hygienists, dental assistants, dentistry students, dentists and prosthodontists who are in direct contact with patients, especially during prosthetic treatments where aerosol-containing dental treatments are common. Dental technicians also have to work on impressions and plaster models taken from potentially contaminated patients due to the inability to ensure 100% sterilization, although the disinfection process is followed with great care. Due to this great risk, prosthodontists postponed some procedures such as crowns, bridges, veneers, inlays and onlays due to aerosol formation during the pandemic and were only able to perform urgent and simple nonaerosol procedures. As safe patient care protocols were learned during the pandemic, dental professionals could incorporate aerosol-containing procedures into their practices using personal protective equipment. The restrictions imposed during the pandemic, the isolation practices, and the news of pandemic-related deaths on social media hurt the mental health of both healthcare workers and patients and their families receiving healthcare services [2–12].

In the literature, for the quantitative measurement of anxiety and depression levels related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) [13], the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [13], the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [14], the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) [5], the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [15], the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7 questionnaire (GAD-7) [11], the Geriatric Anxiety Scale (GAS) [12], various psychometric tools and standardized scales such as the COVID-19 AS (CAS) [12], the COVID-19 Fear Scale (CFS) [13], the COVID-19 Clinical Care AS (CCAS) [10], the Modified Dental AS (MDAS) [10], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [2] were used.

There are also many studies conducted with HADS evaluating both anxiety and depression in different patient groups, patient relatives, healthcare professionals and students during the pandemic period [2, 3, 10, 16–21]. Although there are a small number of nonvalidated questionnaire studies in the literature [1, 7], no study has assessed anxiety and depression using the scale in patients attending prosthodontic clinics during the pandemic period.

Our null hypothesis for the study is that pandemic-related factors affecting anxiety and depression may have decreased in patients attending prosthodontic clinics in the third year of the pandemic. Our study aimed to assess the levels of anxiety and depression and the factors influencing them in patients attending the prosthodontic clinic during a period when pandemic measures were relatively reduced using the HADS.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The present study included volunteer patients aged 18 years and older who applied to the Prosthodontics Clinic in the period between 6 April 2022 and 30 June 2022 who could be contacted.

The use of antidepressants (or other psychiatric medications) was questioned, as this could influence the results of the questionnaire, volunteers who answered ‘I use’, aged under 18, and could not complete questionnaires unaided or would require an interpreter were excluded from the study.

Participants were asked to answer questions that may cause anxiety and depression (Table 1), as well as HADS questions [22]. The questions that could cause anxiety and depression were developed by asking patients who had applied to our prosthodontic clinic 1 week before the study about their reasons for anxiety during the application process. Questions were asked to the patients included in the study by a research assistant trained in questionnaire administration. Our research methodology was thorough, ensuring the validity of our study. All assessments were made by the responsible and co-investigating dentists working in the prosthodontics clinic.

| Question 1. Do you worry about coming to the dental hospital for treatment and examination during the pandemic period? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0. Not at all | 1. Sometimes | 2. Very often | 3. Most of the time |

| Question 2. If there was no pandemic right now, would you worry about coming to the dental hospital for treatment and examination? | |||

| 0. Not at all | 1. Sometimes | 2. Very often | 3. Most of the time |

| Question 3. Do you worry about getting a dental treatment in a crowded environment during the pandemic period? | |||

| 0. Not at all | 1. Sometimes | 2. Very often | 3. Most of the time |

| Question 4. Do you worry about delaying your dental treatments due to the pandemic? | |||

| 0. Not at all | 1. Sometimes | 2. Very often | 3. Most of the time |

| Question 5. Do you worry about infecting your relatives with Covid-19 because you came to the dental hospital during the pandemic period? | |||

| 0. Not at all | 1. Sometimes | 2. Very often | 3. Most of the time |

| Question 6. Do you worry about not being able to get effective healthcare during the pandemic period? | |||

| 0. Not at all | 1. Sometimes | 2. Very often | 3. Most of the time |

| Question 7. Do you worry that constantly using a mask during the pandemic period impairs your oral health? | |||

| 0. Not at all | 1. Sometimes | 2. Very often | 3. Most of the time |

| Question 8. Do you worry about removing the mask that is used to prevent contamination while having the oral examination and dental treatment during the pandemic period? | |||

| 0. Not at all | 1. Sometimes | 2. Very often | 3. Most of the time |

| Question 9. Do you have any chronic disease? | |||

| 0. No | 1. Yes | ||

| Question 10. Have you had your Covid-19 vaccine? | |||

| 0. No | 1. Yes | ||

| Question 11. Have you got Covid-19? | |||

| 0. No | 1. Yes | ||

| Question 12. Do you smoke? ∗ | |||

| 0. No | 1. Yes | ||

- ∗Those who smoked 10 or more cigarettes a day were considered as smokers.

After checking for eligibility, the survey was preceded by a brief introduction outlining the study’s objectives and assuring voluntary participation, anonymity, and confidentiality. The questionnaire took an average of 10 min to complete. Participants’ identity information (name, surname, and ID number) was not recorded. Patient age, sex, level of education, marital status, place of residence, history of chronic disease, COVID-19 disease history, COVID-19 vaccination history, smoking history, and responses to the HADS were recorded.

The HADS is a scale developed by Zigmond and Snaith in 1983 to assess the risk of anxiety/depression and is reliable in healthy populations [22]. The HADS was translated into Turkish, and a validation study was carried out by Aydemir et al. [23]. Of the 14 questions in the HADS, seven questions evaluate the risk of anxiety (HADS-A), and seven questions assess the risk of depression (HADS-D). Responses to the questions are scored on a 0 to 3-point Likert scale. The HADS-A subscale is worth 10 points, and the HADS-D subscale is worth 7 points. Those scoring above these points are considered to be at risk.

2.2. Statistical Analyses

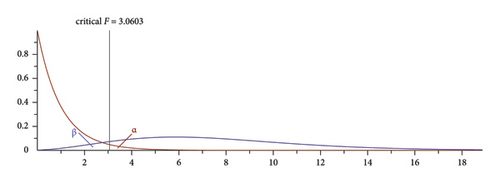

Within the scope of the study, the sample number was calculated with power analysis. In the study to be conducted in a 3-group research design (treatment, examination, control groups) and to test the basic hypothesis with the ANOVA test, the reliability was taken as 95%, the effect level as 0.30 and the power as 90% as a result of the power analysis conducted with G ∗Power (Version 3.1.9.6). In this context, the minimum sample number was calculated as 144 (see Figure 1).

At the end of the study, a post hoc power analysis of the study according to the main hypothesis was calculated with G-Power; the power value was 1,00.

Data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). Frequency and percentage [n (%)] statistics were reported for categorical (qualitative) variables, and mean and standard deviation (mean ± sd) statistics were reported for quantitative variables. Independent groups t- and one-way ANOVA tests were used to compare the measures obtained in the study according to groups. The chi-squared test was used for relationships between grouped variables, and logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors influencing depression and anxiety. All analyses were done at a 95% confidence interval, and p values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.3. Ethical Approval

The current research received ethical approval from the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee at Pamukkale University (Ref #: E-60116787-020-193210) on April 5th, 2022. Patients who agreed to participate were requested to select the option: “I have read the study information, and I agree to participate with my answers to the questionnaire may be used for scientific purposes,” representing the informed consent to participate before moving on to the questionnaire.

3. Results

3.1. The Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants and the HADS Values Obtained According to the Reasons for Application to the Prosthodontics Clinic

When all participants were evaluated, the average age was 48.7 ± 16.39. Of the 194 participants, 164 (84.5%) were aged 18–65, and 30 (15.5%) were aged 66–82. The number of female participants was 98 (50.5%). 90 (46.3%) of the participants had completed primary school or less, 42 (21.6%) had completed high school, and 62 (32%) had finished university (Table 2). 139 (71.6%) of the participants lived in the city center, 139 (71.6%) were married, 65 (33.5%) were retired and 66 (34%) were employed. Of the participants, 140 (72.2%) enrolled for treatment, 41 (21.1%) for assessment and 13 (6.7%) for control (Table 2). 108 (55.7%) of the participants had no chronic diseases, 180 (92.8%) had received the COVID-19 vaccine, and 60 (30.9%) had been infected with COVID-19 at least once. 148 (76.3%) of the participants reported that they did not smoke (Table 2). HADS-A was detected in 82 (42.3%) and HADS-D in 114 (58.8%) of the participants, and the mean HADS score was 15.97 ± 7.66 (Table 2).

| All patients (n = 194) | Treatment (n = 140) | Examination (n = 41) | Control (n = 13) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 48.7 ± 16.39 | 50.84 ± 15.83 | 43.37 ± 15.84 | 42.46 ± 19.71 | 0.013 ∗ | |

| Age groups n (%) | 18–65 | 164 (84.5) | 117 (83.6) | 36 (87.8) | 11 (84.6) | 0.887 |

| 66–82 | 30 (15.5) | 23 (16.4) | 5 (12.2) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Gender | Female | 98 (50.5) | 69 (49.3) | 25 (61) | 4 (30.8) | 0.137 |

| Male | 96 (49.5) | 71 (50.7) | 16 (39) | 9 (69.2) | ||

| Education | Primary school and under | 90 (46.3) | 67 (47.9) | 17 (41.5) | 6 (46.2) | 0.745 |

| High school | 42 (21.6) | 28 (20) | 12 (29.3) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| University | 62 (32) | 45 (32.1) | 12 (29.3) | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Place of residence | City | 139 (71.6) | 95 (67.9) | 34 (82.9) | 10 (76.9) | 0.433 |

| District | 40 (20.6) | 33 (23.6) | 5 (12.2) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Town-village | 15 (7.8) | 12 (8.6) | 2 (4.9) | 1 (7.7) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 55 (28.4) | 36 (25.7) | 13 (31.7) | 6 (46.2) | 0.261 |

| Married | 139 (71.6) | 104 (74.3) | 28 (68.3) | 7 (53.8) | ||

| Profession | Retired | 65 (33.5) | 55 (40.1) | 5 (12.2) | 5 (38.5) | 0.001 ∗ |

| Civil servant | 66 (34) | 41 (29.9) | 23 (56.1) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Student | 20 (10.3) | 11 (8) | 5 (12.2) | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Homemaker | 40 (20.6) | 30 (21.9) | 8 (19.5) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Unemployed | 3 (1.5) | |||||

| Chronic disease | No | 108 (55.7) | 73 (52.1) | 29 (70.7) | 6 (46.2) | 0.078 |

| Yes | 86 (44.3) | 67 (47.9) | 12 (29.3) | 7 (53.8) | ||

| COVID-19 vaccine | No | 14 (7.2) | 8 (5.7) | 5 (12.2) | 1 (7.7) | 0.244 |

| Yes | 180 (92.8) | 132 (94.3) | 36 (87.8) | 12 (92.3) | ||

| Catching COVID-19 | No | 134 (69.1) | 101 (72.1) | 25 (61) | 8 (61.5) | 0.299 |

| Yes | 60 (30.9) | 39 (27.9) | 16 (39) | 5 (38.5) | ||

| Smoking | No | 148 (76.3) | 107 (76.4) | 31 (75.6) | 10 (76.9) | 0.999 |

| Yes | 46 (23.7) | 33 (23.6) | 10 (24.4) | 3 (23.1) | ||

| HADS (mean ± SD) | 15.97 ± 7.66 | 15.53 ± 7.97 | 16.98 ± 7.23 | 17.62 ± 499 | 0.415 | |

| Anxiety n (%) | Yes | 82 (42.3) | 57 (40.7) | 21 (51.2) | 4 (30.8) | 0.353 |

| No | 112 (57.7) | 83 (59.3) | 20 (48.8) | 9 (69.2) | ||

| HADS-A (mean ± SD) | 7.88 ± 4.25 | 7.58 ± 4.37 | 8.71 ± 4.15 | 8.46 ± 2.82 | 0.288 | |

| HADS-A n (%) | 0–10 | 112 (57.7) | 83 (59.3) | 20 (48.8) | 9 (69.2) | 0.353 |

| ≥ 11 | 82 (42.3) | 57 (40.7) | 21 (51.2) | 4 (30.8) | ||

| Depression n (%) | Yes | 114 (58.8) | 79 (56.4) | 25 (61) | 10 (76.9) | 0.317 |

| No | 80 (41.2) | 61 (43.6) | 16 (39) | 3 (23.1) | ||

| HADS-D (mean ± SD) | 8.10 ± 3.91 | 7.95 ± 4.05 | 8.27 ± 3.72 | 9.15 ± 2.88 | 0.544 | |

| HADS-D n (%) | 0–7 | 80 (41.2) | 61 (43.6) | 16 (39) | 3 (23.1) | 0.481 |

| 8–10 | 52 (26.8) | 34 (24.3) | 12 (29.3) | 6 (46.2) | ||

| ≥ 11 | 62 (32) | 45 (32.1) | 13 (31.7) | 4 (30.8) | ||

- Note: p > 0.05 no significant difference; Chi-square test, one-way ANOVA test.

- Abbreviations: HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS-A, hospital anxiety depression scale-anxiety score; HADS-D, hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression score; SD, standard deviation.

- ∗p < 0.05 shows a significant difference.

The mean age of participants presenting for treatment (50.84 ± 15.83) was significantly higher than those presenting for examination (43.37 ± 15.84) and control (42.46 ± 19.71) (p = 0.013). However, no statistical difference was found when the number of patients presenting for treatment, examination, and control was evaluated in age groups (p = 0.887) (Table 2). Regarding the working status variable, the proportion of pensioners was 40.1% in the treatment group, 12.2% in the examination group, and 38.5% in the control group. The distribution of employees was 29.9% in the treatment group, 56.1% in the study group, and 15.4% in the control group. While the distribution was similar for students and homemakers, a statistically significant difference in employment status was found between the groups (p < 0.001). It was found that there were more working people in the study group and more retired people in the treatment and control groups.

No statistically significant difference was found between the treatment, assessment, and control groups in terms of demographic characteristics and HADS scores (p > 0.05) (Table 2). When assessing HADS-A, 57 (40.7%) participants in the treatment group, 21 (51.2%) in the assessment group, and 4 (30.8%) in the control group were found to have anxiety, and no statistically significant difference was found between the groups (p = 0.353). Depression was found in 79 (56.4%) participants in the treatment group, 25 (61%) in the assessment group and 10 (76.9%) in the control group, and no statistical difference was found between the groups (p = 0.317) (Table 2).

3.2. Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression With Other Variables

The mean HADS-D score of smokers (9.07 ± 3.36) was significantly higher than that of nonsmokers (7.8 ± 4.03) (p = 0.036). This may indicate a possible association between smoking and depression status (Table 3).

| Age | p value | Gender | p value | Smoking | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–65 (n = 164) | 66–82 (n = 30) | Female (n = 98) | Male (n = 96) | No (n = 148) | Yes (n = 46) | |||||

| HADS (mean ± SD) | 16.01 ± 7.74 | 15.77 ± 7.38 | 0.872 | 16.72 ± 7.41 | 15.21 ± 7.88 | 0.169 | 15.46 ± 7.84 | 17.63 ± 6.87 | 0.074 | |

| Anxiety n (%) | Yes | 68 (41.5) | 14 (46.7) | 0.742 | 47 (48) | 35 (36.5) | 0.105 | 85 (57.4) | 27 (58.7) | 0.999 |

| No | 96 (58.5) | 16 (53.3) | 51 (52) | 61 (63.5) | 63 (42.6) | 19 (41.3) | ||||

| HADS-A (mean ± SD) | 7.9 ± 4.33 | 7.73 ± 3.84 | 0.842 | 8.46 ± 4.12 | 7.28 ± 4.32 | 0.053 | 7.66 ± 4.29 | 8.57 ± 4.1 | 0.209 | |

| HADS-A n (%) | 0–10 | 96 (58.5) | 16 (53.3) | 0.742 | 51 (52) | 61 (63.5) | 0.105 | 85 (57.4) | 27 (58.7) | 0.999 |

| ≥ 11 | 68 (41.5) | 14 (46.7) | 47 (48) | 35 (36.5) | 63 (42.6) | 19 (41.3) | ||||

| Depression n (%) | Yes | 97 (59.1) | 17 (56.7) | 0.959 | 61 (62.2) | 53 (55.2) | 0.320 | 65 (43.9) | 15 (32.6) | 0.234 |

| No | 67 (40.9) | 13 (43.3) | 37 (37.8) | 43 (44.8) | 83 (56.1) | 31 (67.4) | ||||

| HADS-D (mean ± SD) | 8.11 ± 3.85 | 8.03 ± 4.28 | 0.922 | 8.27 ± 3.82 | 7.93 ± 4.01 | 0.548 | 7.8 ± 4.03 | 9.07 ± 3.36 | 0.036 ∗ | |

| HADS-D n (%) | 0–7 | 67 (40.9) | 13 (43.3) | 0.897 | 37 (37.8) | 43 (44.8) | 0.553 | 65 (43.9) | 15 (32.6) | 0.368 |

| 8–10 | 45 (27.4) | 7 (23.3) | 29 (29.6) | 23 (24) | 37 (25) | 15 (32.6) | ||||

| ≥ 11 | 52 (31.7) | 10 (33.3) | 32 (32.7) | 30 (31.3) | 46 (31.1) | 16 (34.8) | ||||

| Chronic disease | pvalue | COVID-19 vaccine | pvalue | Catching COVID-19 | pvalue | |||||

| No (n = 108) | Yes (n = 86) | No (n = 14) | Yes (n = 180) | No (n = 134) | Yes (n = 60) | |||||

| HADS (mean ± SD) | 15.06 ± 7.86 | 17.12 ± 7.29 | 0.064 | 14.36 ± 7.83 | 16.1 ± 7.66 | 0.414 | 16.56 ± 7.71 | 14.67 ± 7.46 | 0.112 | |

| Anxiety n (%) | Yes | 39 (36.1) | 43 (50) | 0.052 | 5 (35.7) | 77 (42.8) | 0.815 | 60 (44.8) | 22 (36.7) | 0.291 |

| No | 69 (63.9) | 43 (50) | 9 (64.3) | 103 (57.2) | 74 (55.2) | 38 (63.3) | ||||

| HADS-A (mean ± SD) | 7.41 ± 4.41 | 8.47 ± 3.99 | 0.085 | 7.07 ± 4.34 | 7.94 ± 4.25 | 0.463 | 8.1 ± 4.41 | 7.37 ± 3.86 | 0.265 | |

| HADS-A n (%) | 0–10 | 69 (63.9) | 43 (50) | 0.052 | 9 (64.3) | 103 (57.2) | 0.815 | 74 (55.2) | 38 (63.3) | 0.291 |

| ≥ 11 | 39 (36.1) | 43 (50) | 5 (35.7) | 77 (42.8) | 60 (44.8) | 22 (36.7) | ||||

| Depression n (%) | Yes | 58 (53.7) | 56 (65.1) | 0.109 | 7 (50) | 107 (59.4) | 0.682 | 85 (63.4) | 29 (48.3) | 0.048 ∗ |

| No | 50 (46.3) | 30 (34.9) | 7 (50) | 73 (40.6) | 49 (36.6) | 31 (51.7) | ||||

| HADS-D (mean ± SD) | 7.66 ± 4.04 | 8.65 ± 3.68 | 0.079 | 7.29 ± 3.85 | 8.16 ± 3.92 | 0.421 | 8.46 ± 3.83 | 7.3 ± 4.01 | 0.057 | |

| HADS-D n (%) | 0–7 | 50 (46.3) | 30 (34.9) | 0.233 | 7 (50) | 73 (40.6) | 0.688 | 49 (36.6) | 31 (51.7) | 0.060 |

| 8–10 | 28 (25.9) | 24 (27.9) | 4 (28.6) | 48 (26.7) | 42 (31.3) | 10 (16.7) | ||||

| ≥ 11 | 30 (27.8) | 32 (37.2) | 3 (21.4) | 59 (32.8) | 43 (32.1) | 19 (31) | ||||

- Note: p > 0.05 no significant difference; Chi-square test, one-way ANOVA test.

- Abbreviations: HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS-A, hospital anxiety depression scale-anxiety score; HADS-D, hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression score; SD, standard deviation.

- ∗p < 0.05 shows a significant difference.

While 85 (63.4%) of the participants who had not had COVID-19 showed symptoms of depression, 29 (48.3%) of those who had had COVID-19 showed symptoms of depression, and this difference was statistically significant with p = 0.048. These results indicate that individuals who had had COVID-19 had lower rates of depression symptoms compared to those who had not had COVID-19 (Table 3).

Age, gender, presence of chronic diseases, and COVID-19 vaccination were found to have no significant effect on anxiety and depression scores (Table 3).

Educational level and place of residence were found to have no significant impact on anxiety and depression scores (Table 4). Employment status and marital status also had no significant effect on anxiety and depression scores (Table 5).

| Education | p value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary school and under (n = 90) | High school (n = 42) | University (n = 62) | |||

| HADS (mean ± SD) | 15.83 ± 7.33 | 17.55 ± 6.98 | 15.11 ± 8.5 | 0.276 | |

| Anxiety n (%) | Yes | 39 (43.3) | 18 (42.9) | 25 (40.3) | 0.930 |

| No | 51 (56.7) | 24 (57.1) | 37 (59.7) | ||

| HADS-A (mean ± SD) | 7.83 ± 4.05 | 8.5 ± 3.76 | 7.52 ± 4.83 | 0.509 | |

| HADS-A n (%) | 0–10 | 51 (56.7) | 24 (57.1) | 37 (59.7) | 0.930 |

| ≥ 11 | 39 (43.3) | 18 (42.9) | 25 (40.3) | ||

| Depression n (%) | Yes | 54 (60) | 28 (66.7) | 32 (51.6) | 0.293 |

| No | 36 (40) | 14 (33.3) | 30 (48.4) | ||

| HADS-D (mean ± SD) | 8 ± 3.88 | 9.05 ± 3.58 | 7.6 ± 4.11 | 0.169 | |

| HADS-D n (%) | 0–7 | 36 (40) | 14 (33.3) | 30 (48.4) | 0.644 |

| 8–10 | 24 (26.7) | 13 (31) | 15 (24.2) | ||

| ≥ 11 | 30 (33.3) | 15 (35.7) | 17 (27.4) | ||

| Place of residence | pvalue | ||||

| City (n = 139) | District (n = 40) | Town-village (n = 15) | |||

| HADS (mean ± SD) | 15.83 ± 7.54 | 16.15 ± 8.32 | 16.8 ± 7.45 | 0.887 | |

| Anxiety n (%) | Yes | 55 (39.6) | 19 (47.5) | 8 (53.3) | 0.446 |

| No | 84 (60.4) | 21 (52.5) | 7 (46.7) | ||

| HADS-A (mean ± SD) | 7.79 ± 4.2 | 7.95 ± 4.64 | 8.47 ± 3.87 | 0.838 | |

| HADS-A n (%) | 0–10 | 84 (60.4) | 21 (52.5) | 7 (46.7) | 0.446 |

| ≥ 11 | 55 (39.6) | 19 (47.5) | 8 (53.3) | ||

| Depression n (%) | Yes | 79 (56.8) | 26 (65) | 9 (60) | 0.649 |

| No | 60 (43.2) | 14 (35) | 6 (40) | ||

| HADS-D (mean ± SD) | 8.04 ± 3.86 | 8.2 ± 4.19 | 8.33 ± 3.87 | 0.948 | |

| HADS-D n (%) | 0–7 | 60 (43.2) | 14 (35) | 6 (40) | 0.916 |

| 8–10 | 36 (25.9) | 12 (30) | 4 (26.7) | ||

| ≥ 11 | 43 (30.9) | 14 (35) | 5 (33.3) | ||

- Note: p > 0.05 no significant difference; Chi-square test, one-way ANOVA test.

- Abbreviations: HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS-A, hospital anxiety depression scale-anxiety score; HADS-D, hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression score; SD, standard deviation.

| Profession | p value | Marital status | p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retired (n = 65) | Civil servant (n = 66) | Student (n = 20) | Homemaker (n = 40) | Single (n = 55) | Married (n = 139) | ||||

| HADS (mean ± SD) | 15.89 ± 7.63 | 16.14 ± 7.78 | 13.8 ± 8.08 | 16.75 ± 7.35 | 0.564 | 15.38 ± 7.31 | 16.21 ± 7.81 | 0.500 | |

| Anxiety n (%) | Yes | 28 (43.1) | 28 (42.4) | 5 (25) | 19 (47.5) | 0.384 | 19 (34.5) | 63 (45.3) | 0.227 |

| No | 37 (56.9) | 38 (57.6) | 15 (75) | 21 (52.5) | 36 (65.5) | 76 (54.7) | |||

| HADS-A (mean ± SD) | 7.68 ± 4.04 | 7.88 ± 4.45 | 7.1 ± 4.7 | 8.45 ± 4.08 | 0.678 | 7.67 ± 4.21 | 7.96 ± 4.28 | 0.676 | |

| HADS-A n (%) | 0–10 | 37 (56.9) | 38 (57.6) | 15 (75) | 21 (52.5) | 0.384 | 36 (65.5) | 76 (54.7) | 0.227 |

| ≥ 11 | 28 (43.1) | 28 (42.4) | 5 (25) | 19 (47.5) | 19 (34.5) | 63 (45.3) | |||

| Depression n (%) | Yes | 40 (61.5) | 40 (60.6) | 9 (45) | 23 (57.5) | 0.602 | 32 (58.2) | 82 (59) | 0.999 |

| No | 25 (38.5) | 26 (39.4) | 11 (55) | 17 (42.5) | 23 (41.8) | 57 (41) | |||

| HADS-D (mean ± SD) | 8.22 ± 4.17 | 8.26 ± 3.75 | 6.7 ± 3.96 | 8.3 ± 3.69 | 0.420 | 7.71 ± 3.77 | 8.25 ± 3.97 | 0.385 | |

| HADS-D n (%) | 0–7 | 25 (38.5) | 26 (39.4) | 11 (55) | 17 (42.5) | 0.435 | 23 (41.8) | 57 (41) | 0.184 |

| 8–10 | 18 (27.7) | 19 (28.8) | 7 (35) | 8 (20) | 19 (34.5) | 33 (23.7) | |||

| ≥ 11 | 22 (33.8) | 21 (31.8) | 2 (10) | 15 (37.5) | 13 (23.6) | 49 (35.3) | |||

- Note: p > 0.05 no significant difference; Chi-square test, one-way ANOVA test.

- Abbreviations: HADS, hospital anxiety depression scale; HADS-A, hospital anxiety depression scale-anxiety score; HADS-D, hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression score; SD, standard deviation.

3.3. Effects of Independent Risk Factors for Anxiety and Depression

The effect of factors influencing anxiety was assessed using logistic regression analysis (Table 6). The Cox and Snell R2 of the model is 0.287, and the Nagelkerke R2 is 0.387, indicating that the model explains approximately 28.7%–38.7% of the variance in anxiety. The overall significance of the model is statistically highly significant, with an X2 (Chi-square) value of 65.605 and p < 0.001.

| Variables | B-coefficient | SE | Confidence interval | Odds ratio | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −1.769 | 0.408 | 0.170 | 0.000 ∗ | |

| Age (66–82) | 0.234 | 0.486 | 0.488–3.277 | 1.264 | 0.630 |

| Gender (female) | −0.103 | 0.363 | 0.443–1.836 | 0.902 | 0.776 |

| Question 1. Anxiety about coming to the dental hospital for treatment and examination during the pandemic period | 0.769 | 0.275 | 1.260–3.697 | 2.158 | 0.005 ∗ |

| Question 2. If there was no pandemic, anxiety about coming to the dental hospital for treatment and examination | 0.128 | 0.301 | 0.629–2.050 | 1.136 | 0.672 |

| Question 3. Anxiety about having dental treatment in a crowded environment during treatment | 0.100 | 0.321 | 0.589–2.074 | 1.105 | 0.755 |

| Question 4. Anxiety about dental treatments being postponed due to the pandemic | 0.021 | 0.272 | 0.599–1.739 | 1.021 | 0.939 |

| Question 5. Anxiety about infecting relatives with COVID-19 when coming to the dental hospital during the pandemic period | 0.596 | 0.218 | 1.185–2.782 | 1.816 | 0.006 ∗ |

| Question 6. Anxiety about not receiving effective healthcare during the pandemic period | 0.318 | 0.212 | 0.908–2.082 | 1.375 | 0.133 |

| Question 7. Anxiety about constantly using a mask during the pandemic period will harm oral health | 0.227 | 0.244 | 0.777–2.026 | 1.255 | 0.353 |

| Question 8. Anxiety about the mask used during the pandemic period being removed during examination and treatment to prevent contamination | 0.809 | 0.331 | 1.173–4.296 | 2.245 | 0.015 ∗ |

- Note: R2 = 0.287 (Cox and Snell), R2 = 0.387 (Nagelkerke), X2 = 65.605 p < 0.001. Dependent variable: anxiety present = 1, anxiety absent = 0. p > 0.05 no significant effect; logistic regression.

- ∗p < 0.05 shows a significant effect.

The B-coefficient of the variable related to “anxiety about coming to the hospital during the period when pandemic measures are reduced” is 0.769, and the p value is 0.005, which is a significant effect. The odds ratio (OR) is 2.158. The risk of anxiety was found to be 2.16 times higher for those with this concern than for those without.

The B-coefficient of the variable “Concern about transmitting COVID-19 to relatives during the period when pandemic measures are reduced” is 0.596, and the p value is 0.006, which is a significant effect. The OR is 1.816. The risk of anxiety for individuals with this concern is approximately 1.82 times higher than for those without.

The B-coefficient of the variable “Concern about removing the mask during examination and treatment during the period when pandemic measures are reduced” is 0.809, and the p value is 0.015. The OR is 2.245. The risk of anxiety is 2.25 times higher for individuals with this concern. As the p values of the other variables evaluated with logistic regression analysis are between 0.133 and 0.939, they do not significantly affect anxiety in this model.

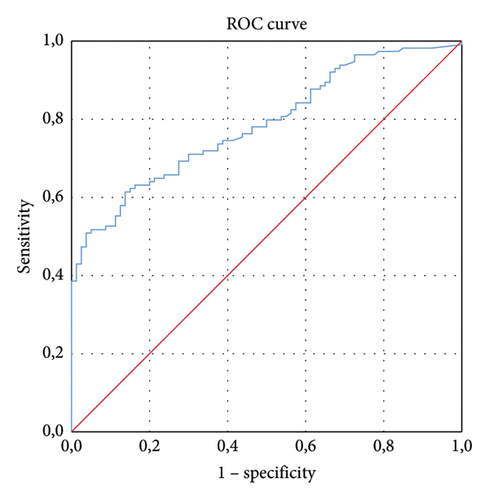

In summary, this model shows that concerns specifically related to the pandemic have a significant effect on individuals’ anxiety status. In particular, ‘fear of going to the hospital during the period when pandemic measures are reduced’ and ‘fear of infecting relatives’ and ‘removal of the mask during treatment and examination’ increase the risk of anxiety. Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted for participants’ anxiety, AUC = 0.787 for questions 1, 5, and 8 (Figure 2).

Logistic regression analysis was used to assess the effect of factors that might be effective on depression (Table 7). The Cox and Snell R2 of the model was 0.316, and the Nagelkerke R2 was 0.424, indicating that the model explained approximately 31.6%–42.4% of the variance in depression. The overall significance of the model is highly statistically significant, with an X2 (Chi-squared) value of 73.592 andp < 0.001.

| Variables | B-coefficient | SE | Confidence interval | Odds ratio | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −2.781 | 0.477 | 0.062 | 0.000 ∗ | |

| Age (66–82) | 0.687 | 0.524 | 0.713–5.550 | 1.989 | 0.189 |

| Gender (female) | 0.211 | 0.364 | 0.605–2.519 | 1.234 | 0.563 |

| Question 1. Anxiety about coming to the dental hospital for treatment and examination during the pandemic period | 1.014 | 0.269 | 1.628–4.670 | 2.757 | 0.000 ∗ |

| Question 2. If there was no pandemic, anxiety about coming to the dental hospital for treatment and examination | 0.342 | 0.298 | 0.785–2.523 | 1.407 | 0.251 |

| Question 3. Anxiety about having dental treatment in a crowded environment during treatment | 0.241 | 0.309 | 0.694–2.332 | 1.273 | 0.435 |

| Question 4. Anxiety about dental treatments being postponed due to the pandemic | 0.003 | 0.253 | 0.611–1.645 | 1.003 | 0.991 |

| Question 5. Anxiety about infecting relatives with COVID-19 when coming to the dental hospital during the pandemic period | 0.503 | 0.214 | 1.087–2.515 | 1.653 | 0.019 ∗ |

| Question 6. Anxiety about not receiving effective healthcare during the pandemic period | 0.254 | 0.206 | 0.861–1.931 | 1.290 | 0.217 |

| Question 7. Anxiety about constantly using a mask during the pandemic period will harm oral health | −0.065 | 0.248 | 0.577–1.523 | 0.937 | 0.794 |

| Question 8. Anxiety about the mask used during the pandemic period being removed during examination and treatment to prevent contamination | 0.120 | 0.308 | 0.617–2.061 | 1.128 | 0.696 |

- Note: R2 = 0.316 (Cox and Snell), R2 = 0.424 (Nagelkerke), X2 = 73.592 p < 0.001. Dependent variable: depression present = 1, depression absent = 0. p > 0.05 no significant effect; logistic regression.

- ∗p < 0.05 shows a significant effect.

The B-coefficient of the variable related to ‘fear of going to hospital during the period of reduced pandemic measures’ is 1.014 with a p < 0.001, which is highly significant. The OR is 2.757. The risk of depression increases by a factor of 2.757 when this worry is present. In other words, individuals with this worry are approximately 2.8 times more likely to be depressed than those without this worry.

The B-coefficient of the variable ‘worry about transmitting COVID-19 to relatives during the period when pandemic measures are reduced’ is 0.503, and the p value is 0.019, which shows that there is a significant effect. The OR is 1.653. People with this worry are 1.653 times more likely to have depression.

As the p values of the other variables evaluated in the logistic regression analysis are between 0.189 and 0.991, they do not significantly affect depression in this model.

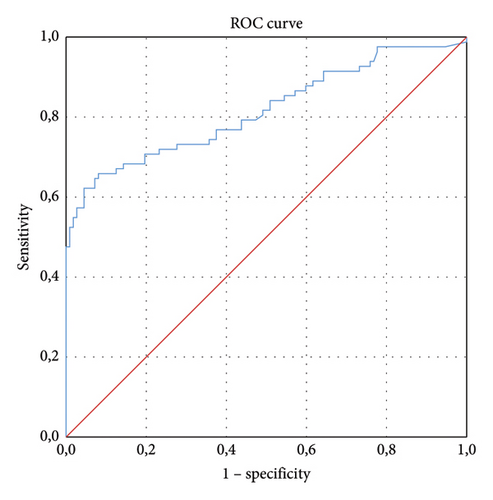

In summary, the logistic regression model shows that pandemic-related worries have a significant effect on the depression status of individuals, and in particular, ‘worries about being hospitalized during the period when pandemic measures are reduced’ and ‘worries about infecting relatives’ increase the risk of depression. Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted for depression in participants, AUC = 0.816 for questions 1 and 5 (Figure 3).

4. Discussion

In this study, we reported a prevalence of anxiety of 42.3% and a prevalence of depression of 58.8%. The mean HADS score was 15.97 ± 7.66. In the evaluation of HADS-A about gender differences, higher values were obtained in women, while men showed better resistance to stress. In our analysis, we observed that older people were more resilient to anxiety and depression in the pandemic, that people living in the city/village, high school graduates, homemakers, and married people had higher HADS scores, and that smokers had higher HADS-D scores. In addition, additional questions asked of the participants identified ‘coming to the hospital during the period when pandemic measures were reduced’, ‘the possibility of transmitting COVID-19 to relatives’, and ‘removing the mask during examination and treatment’ as possible reasons for increasing the risk of anxiety, while ‘coming to the hospital during the period when measures were reduced’ and ‘the possibility of transmitting COVID-19 to relatives’ were identified as possible reasons for increasing the risk of depression.

During COVID-19, patients consulted dentists only for emergency dental treatment because of fear. The only exception was orthodontic treatment [24]. This is because of the fear that treatment interruption will lead to failure. During the pandemic, the adverse psychological effects of not completing treatment were observed in patients [6–9].

In our study, we used the HADS to assess anxiety and depression in patients attending a prosthodontics clinic. However, a literature review showed that other scales have been used in patients attending other nondental clinics. For example, when COVID-19 started in China, the K10 online scale was administered to 1241 participants, consisting of control, orthodontic, and TMD patients. The study found that the average anxiety score for TMD patients was 7.94 ± 3.184 on the K10 scale, with a maximum score of 20 [5]. In a study conducted on 503 patients in a dental hospital in East China during the first period of the COVID-19 pandemic, two new scales related to MDAS and COVID-19, CAS, and CCAS, were used and the highest anxiety scores were found in patients with primary school education [10].

There are also studies in the literature on anxiety and depression in prosthodontic patients using nonscaled questionnaires. For example, in a survey of 328 prosthodontic patients in India six months after the onset of COVID-19, 49.7% of patients reported being very worried about the risk of contracting COVID-19 from the dental clinic [1]. During the first nine months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey, when restrictions were partially lifted, a survey focused on fear or readiness and fear of infection in patients requiring prosthetic treatment found that 73% of respondents considered prosthetic treatment risky [7]. In Serbia, an online survey of 2060 adults was conducted one year after the start of COVID-19 to assess the reasons for dental patient anxiety and measures taken to reduce stress and increase safety. In the study, 70% of respondents reported some level of fear of the ongoing pandemic, 50% were afraid of going to the dentist during the pandemic, 20% considered the dentist’s office to be a hotspot for SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and 43% reported visiting the dentist only in emergencies [6]. However, the above studies did not assess anxiety levels with a scale and did not analyze the impact of the identified risks on anxiety and depression.

There is no anxiety-depression study using HADS regarding applying to a prosthesis clinic in the literature. If we evaluate the results of studies conducted using different scales on prosthesis patients when the first year of the pandemic in Turkey ended, in controlled normalization, when the fear and anxiety levels related to the pandemic and geriatrics were examined with an online survey in 129 geriatric prosthesis patients, anxiety was detected in patients according to GAS, the highest score of which could be 75, and CAS, the highest score of which could be 20 [12]. The GAS mean value was found to be 15.64 ± 9.34, and the CAS mean value was found to be 7.67 ± 2 [12]. In our study using HADS, the anxiety rate was 42.3%, and the HADS-A mean was 7.88 ± 4.25 during the period when COVID-19 measures were reduced. There are studies in the literature indicating that anxiety increased [5–7, 11, 12] or decreased [15, 18, 25] in studies conducted on dental practices during the pandemic.

Similar to the anxiety studies, the literature review of depression studies using other scales in other dental clinics not related to prosthodontics provides results. In a study conducted by Wu et al., in China using the K10 scale, which has a maximum score of 30, the mean depression score in TMD patients was 11.74 (±4.89) [5]. In our study, the depression rate after reduction of COVID-19 measures was 8.10 ± 3.91 in 58.8% of all participants.

In 441 patients receiving TMD treatment in China, the frequency of painful TMD, psychological conditions, sleep, oral health, and quality of life profiles were compared before and after COVID-19 using the Diagnostic Criteria for TMDs (DC/TMD), DASS-21, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP)-TMDs [25]. The authors found that total DASS-21 scores decreased in the post-COVID-19 period (from 31.08 to 27.85 in those with painful TMD and from 22.69 to 21.51 in those with painless TMD) [25]. The same researchers investigated the reason for the decrease in DASS-21 in another study [26]. They suggested that the mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapies they received for their treatment were effective [26]. However, these evaluations include the effects of treatment efficacy on anxiety and depression, not COVID-19. Our study investigated the impact of COVID-19 on anxiety and depression.

In a review conducted before the pandemic by Asher, Asnaani, and Aderka they concluded that studies on anxiety and depression were inconclusive about gender differences and that more research should be conducted using gender-specific, specially designed questionnaires [27]. According to the study conducted by Francis and Surendran 6 months after the start of the pandemic, men were calmer than women, and anxiety about the pandemic was higher in men than women [1]. A survey of 52,730 participants during the first 10 days of the COVID-19 outbreak in China found that women had significantly higher levels of psychological distress and anxiety than men [28]. Many studies have reported that the prevalence of anxiety and depression increased in studies conducted during the pandemic period and that women experienced more severe anxiety symptoms than men [2, 3, 29–33]. This is also consistent with higher HADS scores women than men, although no statistically significant difference was found between the sexes in our study. It is known that anxiety symptoms were more common in women before the pandemic. It has been reported that lifetime stress-related psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety are more common in women. In contrast, externalizing disorders such as aggression are more common in men [34]. This suggests that men and women may have different neural resources in response to stress-related anxiety [35].

Similarly, in two different studies using the HADS in relatives of a total of 120 ICU patients, 60 with COVID-19 and 60 without COVID-19, who were initially admitted to hospital under suspicion of COVID-19 and whose test results were not yet known and whose condition was later clarified [2] and 45 intensive care unit patients with COVID-19 and 45 intensive care unit patients without COVID-19 [3], it was reported that women had higher levels of HADS-A, HADS-D and health anxiety. Another study evaluating 600 valid Self-Rating AS (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) questionnaires in China, where the pandemic first appeared, found that anxiety disorders were three times more common in women than in men [33]. In our study, although there was no statistically significant difference, it was observed that female participants had higher HADS scores than male participants.

Son et al., in a study conducted among students at a large state university in the USA, 71% of the students reported that their stress and anxiety had increased due to the COVID-19 outbreak, and 91% reported that the outbreak had increased their level of fear and anxiety about their health and the health of their loved ones [36]. Kosovali et al., also evaluated the factors influencing depression and anxiety in the relatives of patients followed in the COVID-19 ICU. The HADS was administered to the patient’s relatives before and after the COVID-19 PCR test result. Rates of anxiety (51.6%) and depression (70%) increased in relatives of patients who learned that their patients had COVID-19 (+), whereas rates of anxiety (40%) and depression (65%) decreased in relatives of patients with COVID-19 (−). It was concluded that the pandemic increased depression and anxiety in relatives of patients [2]. In our study, the incidence of anxiety was 42.3%, while the incidence of depression was 58.8%. The reasons why the rates of anxiety and depression were higher in this study than in ours may be because this study was conducted at the beginning of the pandemic, and the relatives were admitted to ICU. Another reason for the lower rates in our study may be the decrease in uncertainty about the transmission and treatment of the disease, the decline in mortality rates compared with the beginning, and the reduction of restrictions throughout the country.

In a study conducted at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was found that dental patients did not prefer a crowded waiting environment in the institutions where they would apply, so they first went to private clinics, which they considered less risky and then to university and state hospitals [37]. Despite the crowded environment in university hospitals, the presence of academic oversight mechanisms due to quality standards and the need to set an example for students may be the reason why individuals perceive faculty clinics as less risky than other public institutions.

A pre-pandemic study used the HADS to assess anxiety, depression, and related factors in patients seeking outpatient dental care. It was found that women, those who had repeated tooth extractions and dental treatments, those with chronic diseases, and those who constantly consumed alcohol were more prone to anxiety. It was also found that those with primary school education, those with periodontitis, those who repeatedly visited the dentist, those who constantly used alcohol and cigarettes, and those who irregularly brushed their teeth were more prone to depression [16]. However, the results of this study are independent of the pandemic period.

Another study conducted at the beginning of the pandemic found no significant difference according to the educational level of the participants. However, it has been observed that the place of residence and the presence of people affected by COVID-19 in the area of residence, smoking and alcohol consumption lead to an increase in anxiety [38] Similarly, in our study, although no significant relationship was found between the HADS-A score and the HADS score, which was higher in smokers compared to nonsmokers, a significant difference was found between the HADS-D score in smokers compared to nonsmokers (p = 0.036; p < 0.05). In addition, although there was no statistically significant difference, an increase in the HADS score was found in those living in town/village (16.8 ± 7.45). The presence of COVID-19 sufferers in this area may also have had an effect.

A survey conducted in India 6 months after the pandemic began reported that patients were concerned that the pandemic and aerosol treatments would be affected. According to the survey results, the reasons for this concern were that patients would have to pay for the COVID-19 screening test, which should be done before treatment, and the possibility of additional financial problems related to dental treatment that would have to be postponed [1, 9]. In our study, HADS-A and HADS-D scores were lower despite aerosol therapies. The lower scores were because the government covered the cost of the COVID-19 screening test, and patients postponed treatment only because of possible contamination. At this point, teledentistry could be a solution to reduce the anxiety of patients coming for screening and control. Teledentistry can provide an effective solution even without a visit to the dentist during the pandemic by giving expert advice and guidance. Face-to-face examination is critical in prosthetic treatment for accurate diagnosis. Even if teledentistry is insufficient compared to other branches of dentistry, it can also contribute to more effective technical communication between the prosthodontist and the laboratory technician [39].

In our study, when we used logistic regression analysis to assess whether participants’ answers to the probable cause questions were independent risk factors for anxiety and depression, we found that ‘coming to the hospital’, ‘not being able to wear the patient’s mask while in the chair for examination or treatment’ and ‘risk of transmitting the disease to relatives’ in the event of infection were reasons for an increase in HADS-A results, whereas ‘coming to the hospital at the end of the pandemic’ and ‘risk of transmitting the disease to relatives’ were reasons for an increase in HADS-D scores. Kosovali et al., found that ‘having patients admitted to ICU due to the pandemic’ was an independent risk factor for anxiety and ‘having limited visits to ICU’ was an independent risk factor for depression in their assessment using HADS in relatives of patients followed up in COVID-19 ICU during the first year of the pandemic [2].

In two different studies where the anxiety and depression of patients with TMD (temporomandibular disorder) were evaluated with HADS, the effects of COVID-19-related stress on anxiety and depression were examined. It has been reported that “social isolation applied during the COVID-19 pandemic” and “TMD-related symptoms” affected the prevalence of anxiety and depression [30, 40]. It has also been suggested that the HADS scale be widely used in studies evaluating the effects of COVID-19-related stress on depression and anxiety. It has been reported that standardization can be achieved in the comparison of study results in this way [20].

The traditional workflow used in prosthetic dentistry when producing prostheses, especially during the pandemic, may cause the saliva and blood of patients carrying COVID-19 to be transported to laboratories with prosthesis impressions, and as a result, clinic and laboratory workers may also become infected with COVID-19. COVID-19 may also be transmitted from infected healthcare workers to patients applying to the prosthesis clinic [41]. Therefore, instead of using manual applications in the workflow, digital methods in dentistry will prevent possible infections and create safer environments for patients and workers. Thus, patients’ concerns about infection may also be reduced [42]. For this purpose, a pivotal role could be assumed by the use of recently introduced technologies such as smartphone applications [43], and artificial intelligence [44] in order to improve knowledge and the management about worry of applying to the prosthodontics clinic.

Due to the pilot nature of this study, generalizations cannot be made. It would be valuable to conduct a similar study with a larger population in a general dental setting after the pandemic to obtain a patient perspective on the evolution of dental care.

4.1. Limitations

The lack of clinical trials and the single-center nature of the study limited the assessment of the effect of the referral center on anxiety and depression.

5. Conclusions

As a result, we can conclude that patients without COVID-19 who applied to the prosthodontics clinic in the third year of the pandemic, when measures were reduced, were smokers and more prone to depression. Again, we can say that applying to the prosthodontic clinic during this period and worrying about infecting their relatives with COVID-19 are factors that increase both anxiety and depression and removing the mask during examination and treatment are factors that increase anxiety.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Pamukkale University-Kinikli Campus (Approval number: E-60116787-020-193210). All participants were informed about the purpose and the procedure of the study before they signed the informed consent forms. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Disclosure

A part of this study was presented at the 29th IZDO International Scientific Congress as an oral presentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

H.L.E.S. contributed to conception, design, data interpretation, statistical analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript.

S.C.S. contributed to conception, design, data interpretation, statistical analysis, and manuscript writing.

C.K. contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, recruitment of participants, and manuscript writing.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The manuscript was totally drafted and written by the authors, without including any external individual.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The raw data can be obtained upon request from the corresponding author.