The Potential Psychological Advantages of the Focusing-Oriented Therapy: A Pilot Quasiexperimental Study of “Proficiency as Focusing Partner” Training Workshop on Self-Compassion

Abstract

Background: Focusing therapy, formulated by Eugene Gendlin (1969), is a body-centered technique that targets bodily sensations and aims at promoting self-care, self-awareness, and self-soothing. Focusing therapy helps people to be more aware of their inner feelings, achieve peace with a purpose without being overwhelmed by anxiety or depression, and enhance mindfulness and self-compassion. Focusing is therefore seen as a tool for developing self-compassion, thereby focusing on our inner feelings and needs and embracing and acknowledging our inner senses. However, there is a dearth of research on practical focusing therapy training workshops for general adults. Therefore, this study aims to be the first research study to investigate the effect of a complete four-level focusing-oriented workshop on self-compassion.

Method: Participants in this study were recruited using convenience sampling, specifically targeting those who had applied for the “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training workshop. 16 participants applied and actively engaged in all four levels of the workshop. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire after finishing the second, third, and fourth levels of the workshop to analyze the influence of different levels of the workshop. The one-way repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the continuous changes in self-compassion across the three time points within the group.

Results and Conclusion: This pilot study addresses the lack of research on focusing therapy training workshops for the general population. The findings suggest that the “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training workshop can significantly improve self-compassion, mainly by reducing negative self-compassion. However, further development of evidence-based focusing-oriented interventions is needed.

1. Introduction

Gendlin [1] created focusing therapy, a body-centered, experiential technique for self-care, self-awareness, and self-soothe. Focusing therapy closely adopted Gendlin’s six-step focusing method [2], which includes (1) clearing a pace, (2) choosing a particular issue, (3) handle/symbol, (4) resonating, (5) asking, and (6) receiving. The first three steps are implemented through acutely aware of the bodily sensations that appear in reaction to a particular circumstance or issue and using these feelings as an umbrella for investigating and comprehending one’s inner experience. While in focusing therapy, these bodily sensations are referred to as “felt sense.” “Felt sense” refers to an embodied, nonverbal awareness of a situation or problem, and it develops in the body as a bodily sensation or feeling [3]. It is, therefore, considered an unlimited, innate perception that transcends cognitive analysis or intellectual understanding. The felt sense is frequently interpreted as an indistinct or fuzzy sensation in the body, but with calm attention and investigation, it can develop into something more conscious and significant. Hence, the felt sense could be expressed and presented in words, phrases, images, or gestures, referred to as symbols in focusing therapy. Instead of depending primarily on verbal communication or cerebral analysis, this technique lets the body direct the inquiry. With these symbols, focusing therapy assists clients in externalizing and crystallizing their emotions and sentiments into a more tangible form. For example, a client might use art materials or other objects to create a symbol representing their felt sense. Through exploration and interaction with this symbol, the client can better understand their inner experience. Through symbols in focusing therapy, clients are given a safe and supportive space to explore their emotions and feelings without being judged. By externalizing and crystallizing these experiences, clients can gain a deeper understanding of themselves and their inner world. At the same time, clients can gain a new perspective on their inner world, seeing it from a third-person perspective. This can help them be more mindful at a distance, allowing them to observe their negative feelings without being absorbed or overwhelmed by them. This process can also help the client gain greater control over their emotions and feelings. Hence, numerous emotional circumstances, such as emotional challenges, relational concerns, self-criticism, and emotional blocks created by core values, are expected to be soothed through focusing-oriented approaches.

However, having (1) clearing space, (2) experiencing bodily sensations in response to a particular issue, and (3) externalizing it through symbols are only considered the early stages of the focusing process; (4) resonating, (5) asking, and (6) receiving are considered essential steps in order to be progressive and to release emotional or cognitive tension raised from that particular issue, or even self-critique or values in some mentally diagnosed patients, and this requires deeper communication and partnership between the client and the focusing partner. The purpose of resonating is to facilitate a body sense of what is authentic and accurate, whereas “asking” facilitates an intimate connection with self and symbols from felt sense, affirming that the questions and answers are within each person’s embodied understanding [4]. As an example, you might ask yourself, “What makes you so dark in color?” or “What is needed?.” Finally, “receiving” refers to unlocking the blocks presented in the symbol with wisdom, hearing their needs and releasing or being friendly with them, thus having more positive emotions in seeking solutions. Hence, language is another critical focus of focusing therapy. Cornell and McGavin [5, 6] have emphasized the importance of language in focusing therapy. She has developed a method called “inner relationship focusing,” which emphasizes the language and inner dialog that clients use to describe their felt sense.

Cornell [5] claims that a client’s capacity to connect with and explore their felt sense can significantly impact the language they use to convey their inner experience. For instance, when clients use critical or judgmental language about themselves, it may be difficult for them to explore their felt sense nonjudgmentally. In addition, Weiser Cornell established an extraordinary language-based approach called “focusing partnership,” in which two persons alternately focus on and verbalize their felt sense. In this process, the partner offers the focuser a nonjudgmental and supportive space to explore their inner experience. Through verbalizing and repeating the focuser’s symbols, the partner can help the focuser become more aware of their inner dialog and how it affects their emotions and feelings by focusing on language. The goal is to encourage individuals to become more conscious of their language and utilize it in a supportive and loving manner to develop a more supportive and caring relationship with themselves and their inner experience.

1.1. Focusing and Mental Well-Being

Focusing has been found to promote emotional regulation, reduce anxiety and depression, and enhance mindfulness, self-compassion, and overall well-being [7]. Focusing therapy showed effectiveness in reducing self-doubt and releasing emotional blocks of core values among immigrants [8], as well as creating contemplation states, negative but manageable awareness, and a certain extent of self-acceptance among drug and alcohol addict patients [9].

Self-compassion is treating oneself with kindness and compassion, caring for yourself as you would your friend. It involves caring for and loving your feelings of pain, failure, and inadequacy rather than harshly criticizing, blaming, or denigrating yourself. Self-compassion also aids stress reduction, enhances self-worth and self-assurance, and improves people’s ability to cope with obstacles [10]. In their research, Aoki and Ikemi [11, 12] developed a scale specific to focus, called the Focusing Manner Scale (FMS). The scale is designed to examine the degree to which focusing attitudes and practices, including acceptance of experiences (i.e., bodily sensation, felt sense, and symbols), becoming aware of these experiences, and finding a comfortable distance from these experiences, are present after practicing focusing. It was correlated with significant psychological-related measurements, including the Self-compassion Scale, General Health Questionnaire, Self-actualization scale, resilience scale, self-affirmation scale, general self-efficacy scale, and other related scales. Hence, focusing practice is therefore seen as an approach that can aid the development of self-compassion by focusing on our inner feelings and needs, embracing and acknowledging them, and learning to be attentive to our inner senses.

In research, focusing therapy is mainly adopted in the form of art therapy as an integrative approach, thus naming it as focusing-oriented art therapy (FOAT). Weiland [13] indicated that a 2-day FOAT session significantly reduced participants’ stress levels and enhanced their self-compassion. As a mindfulness-based approach, FOAT’s theoretical framework was established on mindfulness and compassion as its foundational principles. Most FOAT activities, for instance, FOAT check-in, clearing a space with the arts, and theme-directed FOAT, are expected to cultivate mindfulness and compassion [14, 15]. In addition to mindful body awareness and nonjudgmental description of symbols, the presence of a focusing partner and listening and reflecting with the therapist are considered to reveal the sense of common humanity in self-compassion through articulated mirroring and emphatic understanding. Moreover, Rappaport (2009) introduced FOAT’s potential effect on trauma patients. The paper documented the advantages of FOAT in cultivating body awareness, breathing awareness, grounding, and emotional safety. In FOAT, patients got empathic understanding from others, especially through artistic mirroring and body mirroring exercises in FOAT. Hence, it is documented that FOAT promoted empathic attunement, enabled emotional externalization and distancing, bearing witness, documented change, and carried forward nonjudgmentally, thus creating inner knowing, resilience, and empowerment. Art therapy is a form of therapy that uses various art materials and creative processes to facilitate expression and communication. FOAT combines these two approaches by using art-making as a way to facilitate the focusing process, thus offering a unique and powerful way to facilitate personal growth and healing by integrating the mind–body connection through art-making and focusing [16, 17]. Nevertheless, no standardized intervention protocols and durations are indicated. It could be interpreted that focusing therapy is still considered a practical therapeutic technique in counseling and clinical psychology, which tends to be reported in case studies.

In other similar clinical-focused therapy interventions, such as compassion-focused therapy, a systematic review [18] summarized the average intervention duration as 4–8 weeks or even longer, providing an evidence-supported intervention protocol for generalization and replication. Research studies in the systematic review have also successfully reported robust improvement in self-compassion, self-esteem, self-reassurance, and depression reduction. However, only two focusing intervention studies have been published in recent years, including a 4-week online focusing intervention for general adults and a 2-day session for cancer patients [19, 20]. They evidenced the effect of focusing practice on enhancing mental well-being and reducing mental distress, yet without a structured intervention protocol.

1.2. Purpose

Despite the limited research on focusing-oriented therapy, art therapy, and clinical interventions, the review of FOAT and the documentation of the focusing-oriented method have highlighted its potential psychological benefits. Focusing appears to offer a unique and powerful way to access and understand one’s inner experience, promoting personal growth and healing. Meanwhile, structured group–based interventions and programs should be involved in the community to create more evidence-based outcomes. Hence, the current study aims to address the research gap to be the foremost research study to investigate the effect of a structured “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership,” completing a four-level focusing-oriented workshop on self-compassion.

2. Method

2.1. Study Design and Participants

The pilot study is a single-group intervention study. Participants were recruited using convenience sampling, specifically targeting those who had applied for the training workshop. The recruited participants were required to be aged 18 or above and literate in Chinese. A total of 16 participants applied and actively engaged in all four levels of the workshop. Participants were blinded to the assessed outcomes.

2.2. Intervention

In the field of focusing therapy, “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training is a recognized program by the International Focusing Institute. The training consists of four levels and is typically offered to social workers, counselors, and other healthcare professionals interested in focusing therapy. After completing the “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training, individuals are recognized as “focusing partners” who are able to practice focusing with clients and other service recipients.

In this single-group pilot intervention study, the “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training was organized by the university and facilitated by a certified focusing professional (Trainer). The entire “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training consists of four levels; each level of the training was a 2-day workshop that lasted 8 hours per day. Participants were asked to sign the informed consent before the commencement of the training. Moreover, they were asked to complete the questionnaire after finishing the second, third, and fourth levels of the workshop to analyze the influence of different workshop levels, as focusing therapy comprises continual advancement and development. Researchers could track participants’ progress and quantify any potential changes in their experiences and outcomes by collecting data at different times throughout the workshop.

The content for the “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training is meticulously aligned with the framework provided by The International Focusing Institute to obtain the Proficiency in Focusing Partnership Award. The training comprises Level 1, encountering the inner relationship, which emphasizes achieving clear space and discovering the felt sense; Levels 2 and 3, accompanying the inner relationship, which centers on externalizing symbols to enhance listening skills to those symbols and understanding how to engage with various parts, aspects, conflicting voices, and decision-making; and Level 4, the path of the companion, which focuses on resonating, asking, and receiving to improve empathic listening and responses [21, 22].

2.3. Instrument

The Chinese version of the Self-Compassion Scale–Short Form [23, 24] was used to assess self-compassion. The Self-Compassion Scale consists of 12 items, and the overall score determines the level of self-compassion. The items were assessed on a five-point scale (1 being almost never and 5 being almost always). The 12-item measure has shown adequate reliability and validity in the Chinese population. The scale includes six factors, positive self-compassion: self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness; negative self-compassion: self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification, the same as the original scale. The negative self-compassion items were reverse-coded to calculate the total score. While, in the current study, the level of negative self-compassion and positive self-compassion will be investigated separately as well.

2.4. Data Analysis

Demographic information, including age and gender, was collected. SPSS 27.0 Version (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America) was used to analyze the data. No missing data were found, and a normality assessment was performed to detect necessary non-normality patterns and outliers. The one-way repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the continuous changes in self-compassion across the three time points (i.e., completion of the second, third, and fourth levels) within the group. The post hoc analysis used Bonferroni correction to highlight the differences between time points using mean differences within 95% confidence intervals. If the sphericity assumption was violated, the Huynh–Feldt corrections were used if Epsilon was 0.75 or above [25].

3. Results

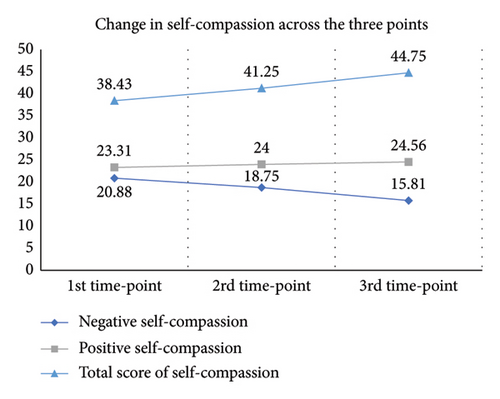

A total of 16 participants applied and engaged in all four levels of the workshop. All participants were of ages 18–25, with 76% of them being female. Participants are students who mainly studied psychology and social work. The baseline average level of self-compassion of these participants was 38.44 (sd = 1.67). With the data fitting the normality assessment, the repeated-measure ANOVAs demonstrated a significant reduction in the level of negative self-compassion, with F(1.76, 26.40) = 6.15 and p = 0.008. In addition, there was a significant increase in the total self-compassion score, with F(2, 30) = 6.13 and p = 0.006. These results showed a large effect size of Cohen’s f = 0.6. In the pairwise comparison, both outcomes showed significant differences only between the first and the third time points, as well as between the second and third time points. While the participants did not show significant differences in the change of positive self-compassion, there was a gradual increase in the score in general. Please see Figure 1 for the line chart of the change in self-compassion across the three time points.

4. Discussion

The present paper expounds upon the fundamental elements and perspectives of focusing therapy, which has been studied in the existing literature and documents primarily in the form of FOAT. However, there is a dearth of research on practical focusing therapy training workshops for general adults. This paper addresses this gap and provides a pilot study investigating the impact of “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training workshops on self-compassion. The practice of focusing involves the cultivation of mindfulness, self-awareness, and self-discovery, which are essential for promoting psychological well-being. The findings of the pilot study suggest that “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training workshops significantly improve self-compassion, especially in the reduction of negative self-compassion. The results of the pilot study suggest that the “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training workshops had a significant impact on the self-compassion of participants. The study also indicates that the use of focusing therapy could contribute to improving self-compassion, which could, in turn, help individuals dealing with mental illness to develop self-kindness and self-awareness in a mindful and less self-critical way.

As a pilot study, there are a few unavoidable limitations that need to be addressed. Despite being a pilot study, there was no control group, and it wholly depended on the volunteer application of the training workshop as the recruitment procedure of the participants. Thus, no comparison could be made between the self-compassion outcomes of those trained and those not trained. Moreover, as the training aimed to benefit healthcare professionals, the participants likely entered with moderate-to-high levels of positive self-compassion and well-being. This may have limited the degree of change observed. In addition, the four levels of training workshops only lasted for 2 days each. The introductory first level especially may have been insufficient to produce notable effects. Pairwise comparisons also revealed significant differences between the second and third, and first and third time points, suggesting the brief duration could have constrained outcomes.

4.1. Generalizability and Future Research Directions

Focusing therapy or other focusing-oriented approach interventions have been considered as scarce in the field of research. The current review and pilot study would serve as a pioneer in showing the effect of focusing on enhancing individuals’ self-compassion and other expected mental well-being. However, in order to enhance the applicability and suitability of the “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training for the general population, it should not be limited to healthcare professionals but also the general public, including adolescents. Based on the evidence retrieved from the current pilot study, it can be concluded that the training content had a significant impact on individuals’ self-compassion. The training workshops were brief (2 days per level). Therefore, the research outcome supports the idea of constructing an evidence-based, focusing-oriented intervention, similar to the 8-week mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention [26] or the 8-week mindful self-compassion intervention [27]. A focusing-oriented intervention structured in the same way as the referenced 8-week programs could allow for standardized delivery and evaluation across settings/studies. This contributes to a more solid evidence base. With additional development and testing, concentrating treatments could be introduced as a therapy option in clinical practice and community mental health programs. Moreover, the study lacked long-term follow-up, making it unclear whether improvements in self-compassion persist over time. Mental health interventions often require enduring changes, and sustained effects are critical for clinical relevance. Future research should incorporate follow-up assessments at 3–6 months postintervention to evaluate the retention of benefits.

Furthermore, objective measurements such as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) can be applied to monitor variations in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in the brain’s cortical areas during focusing-oriented practice [28]. It has been extensively utilized to investigate the brain underpinnings of self-related processing and empathy. fNIRS is commonly used in mindfulness-based treatments since it facilitates the identification of mental fatigue, cognitive function, changes in attentional performance, and activation of brain neuroconstructs, displaying people’s attentional control and emotional regulation [29, 30]. Using fNIRS to measure prefrontal activity provides objective evidence of real-time changes in prefrontal activation during focusing-oriented practice. This can help compare the effects of such practice on self-representation and other associated brain systems, both during and without practice. Incorporating neuroimaging techniques such as fNIRS can provide objective biological validation of reported psychological outcomes and help identify significant active elements within focusing-oriented practices in the intervention.

5. Overall Conclusions

This pilot study aims to address the lack of research on focusing therapy training workshops for the general population. The findings suggest that the “Proficiency in Focusing Partnership” training workshop can significantly improve self-compassion, particularly by reducing negative self-compassion. These findings align with theoretical frameworks positing that focusing therapy fosters self-awareness and mindfulness, which are core mechanisms in self-compassion development [10, 31]. The reduction in negative self-compassion mirrors outcomes seen in mindfulness-based interventions, where decreased self-criticism often precedes gains in self-kindness [32]. However, the lack of a control group and reliance on self-report measures limit causal inferences. Further development of evidence-based focusing-oriented interventions is needed. Structuring such programs comparably to the existing mindfulness-based interventions may facilitate standardized implementation and evaluation. Incorporating refinements such as objective biofeedback might help strengthen the evidence foundation and clarify how focusing-oriented interventions uniquely benefit individuals in various psychological aspects, including cognitive function and overall mental well-being. These preliminary findings provide initial optimism around the clinical potential of focusing therapy training on improving well-being.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific funding support from any organization or funding agency. The author conducted the study independently and self-funded the research.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express their sincere appreciation to Certified Focusing Professional Trainer, Jessie, a dedicated and insightful trainer, for graciously granting permission to include the self-compassion questionnaire in the evaluation form used during their training sessions. This permission was not only invaluable for the purpose of our research but also contributed to the personal growth and development of the participating students. This research endeavor was driven by a shared commitment to improving teaching practices and fostering the inner personal development of students. The collective efforts of all those involved have contributed significantly to the advancement of knowledge in this field, and we are deeply grateful for their contributions.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.