Epidemiology and Long-Term Trends of Suicide-Related Hospitalizations in Taiwan: A Population-Based Study

Abstract

Background: Suicide is a significant public health issue worldwide, with profound impacts on individuals and society. In Taiwan, suicide has consistently ranked among the leading causes of death, with rates continuing to rise in recent years. Hospitalization due to suicide attempts or injuries is a key indicator of the severity of the issue and the effectiveness of preventive interventions. While suicide mortality has been widely studied, limited research has examined long-term trends in suicide-related hospitalizations, including variations by the methodology, gender, age, and region. Identifying these patterns is essential for developing effective suicide prevention programs and addressing high-risk populations.

Objectives: To examine the epidemiology of suicide-related hospitalized patients, including overall suicide mortality, hospitalization incidence, hospitalization prevalence, and fatality rates—and to analyze long-term trends in Taiwan.

Methods: This study utilized data from three national databases: the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), the Household Registration Database, and the Cause of Death Data in Taiwan. Information on 66,399 hospitalized patients with suicide-related injuries from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2018, was collected from the NHIRD, and the Cause of Death Statistics from 1998 to 2020 was analyzed.

Results: The proportion of females hospitalized for attempted suicide (55.01%) was higher than that of males (44.99%). Hospitalizations were predominantly higher among individuals aged 20–39 years (46.63%). The three most common suicide methods were ingestion of solid or liquid substances (62.75%), jumping from buildings (19.13%), and burning charcoal (12.08%). Among these, females had higher rates of ingesting solid or liquid substances (11.32/100,000), cutting with tools (0.15/100,000), and jumping from buildings (3.2/100,000), whereas males had higher rates of burning charcoal (1.41/100,000), hanging (0.39/100,000), and firearm use. Regarding age, young adults aged 20–49 years were more likely to attempt suicide by jumping from buildings, burning charcoal, or using gas, while older adults aged 65 years and above predominantly used ingestion of solids, hanging, or cutting tools. Furthermore, suicide methods exhibited substantial regional variations.

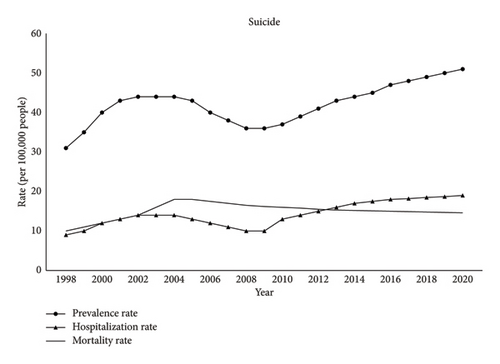

Conclusions: From 1998 to 2020, suicide-related hospitalizations, mortality, and morbidity rates increased in Taiwan, underscoring a pressing public health concern that warrants immediate attention. The marked rise in hospitalization rates indicates that suicide attempts may be becoming more frequent or severe, emphasizing the urgent need to strengthen early intervention strategies.

1. Introduction

Suicide, though not classified as a disease, remains a major public health concern. In 2019, an estimated 703,000 people worldwide died by suicide, with the highest rates observed in Eastern Europe, high-income Asia-Pacific, and Southern Africa [1]. Suicide methods vary by region—hanging is common globally, pesticide ingestion is prevalent in Asia and Latin America, and firearm-related suicides dominate in the United States [2]. In Taiwan, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in 2021, with a mortality rate of 15.3 per 100,000 people [3]. While the rate peaked in 2006 and later declined, it has fluctuated since 2011 without a clear downward trend [4].

Despite extensive research on individual suicide cases in Taiwan, long-term trends in mortality, hospitalization incidence, and prevalence remain underexplored. Moreover, most studies rely on hospitalization data, potentially underestimating suicide attempts that do not result in medical treatment [5]. To address this gap, this study integrates three national databases—the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), the Household Registration Database, and the Cause of Death Data. This study analyzes suicide mortality rates, hospitalization incidence and prevalence, fatality percentages, and long-term trends among inpatients in Taiwan using integrated data from three national databases. This comprehensive approach aims to provide a more complete epidemiological perspective on suicide in Taiwan.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

This study utilized data from three national databases in Taiwan, covering the period from 2000 to 2018. The target population included all individuals aged 0–110 years within Taiwan’s population of 23.74 million. Data were pooled from the following sources: NHIRD, the Household Registration Database, and the National Cause of Death Statistics File. The NHIRD is maintained by the Health Insurance Administration under the Ministry of Health and Welfare and is primarily used to calculate medical costs. It contains detailed information on personal medical history, outpatient and emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and medication use from 2000 to 2018 [6]. The Household Registration Database collects demographic information, including the marital status and income. The National Cause of Death Statistics File provides data on sex, date of birth, date of death, and cause of death from 1998 to 2020 [7]. By integrating these three databases, we calculated overall suicide mortality, hospitalization incidence, hospitalization prevalence, and the percentage of suicide-related fatalities among hospitalized patients.

2.2. Definitions

- 1.

Prevalence rate: The total number of hospitalizations for suicide attempts (including repeat cases) per 100,000 people.

- 2.

Incidence rate (hospitalization rate): The number of hospital admissions due to suicide attempts per 100,000 people.

- 3.

Mortality rate: The rate of death due to suicide within the population, typically calculated per 100,000 individuals per year.

- 4.

Fatality rate: The proportion of individuals who die after hospitalization for a specific condition, distinguishing between suicide-related and nonsuicide cases.

- 5.

Trend: A pattern or change in the data over time, often analyzed to assess long-term shifts in suicide rates.

2.3. Study Design and Data Processing

This retrospective cohort study analyzed 66,399 patients hospitalized for suicide attempts in Taiwan between 2000 and 2018. To ensure data reliability, a systematic inclusion, exclusion, and cleaning process was applied.

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- •

Suicide-related hospitalizations were identified using ICD-9-CM codes E950–E959 (suicide or deliberate self-harm).

- •

Inpatient admission was required, meaning outpatient visits and emergency department cases without subsequent hospitalization were excluded.

- •

Patients aged 0–110 years were included.

- •

Only cases treated in medical institutions within Taiwan were considered.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria and Data Cleaning

To enhance data reliability, a structured data cleaning process was implemented:

2.3.2.1. Handling Missing and Incomplete Data

Records with critical missing data (e.g., hospitalization date, method of suicide, age, or gender) were excluded.

Records with partial missing data (e.g., discharge status and length of stay) were retained if they had at least 70% completeness in key variables.

For cases missing specific details (e.g., method of suicide), information was cross-validated with three national databases (NHIRD, Household Registration, and Cause of Death Data). If discrepancies remained unresolved, cases were excluded.

2.3.2.2. Ensuring Consistency and Cross-Validation

- •

NHIRD: Verified hospitalization details and treatment records.

- •

Household Registration Database: Ensured demographic consistency.

- •

Cause of Death Data: Differentiated between fatal and nonfatal suicide attempts.

- •

If the recorded method of suicide differed between databases, NHIRD data were prioritized.

- •

Cases with persistent inconsistencies (e.g., duplicate entries with conflicting details) were excluded.

2.3.2.3. Managing Duplicate Records

To avoid overrepresentation, patients with multiple hospitalizations were identified using unique patient IDs.

Only the first hospitalization record per patient within the study period was retained to prevent bias from repeat admissions.

Repeat cases were categorized separately for future trend analysis but were excluded from incidence calculations.

This rigorous approach ensured data integrity, reduced selection bias, and improved the accuracy of epidemiological estimates.

2.3.3. Categorization of Suicide Methods (ICD-9-CM Codes)

- 1.

Poisoning by solid or liquid substances (E950): Intentional ingestion of toxic substances, including pesticides, medications, household chemicals, or other poisonous substances.

- 2.

Gas poisoning (E951): Inhalation of toxic gases such as carbon monoxide from motor vehicles, stoves, or other sources.

- 3.

Drowning or submersion (E952): Intentional self-harm by drowning in bodies of water such as rivers, lakes, or bathtubs.

- 4.

Charcoal burning (E952.0—carbon monoxide poisoning from utility gases): Specific method involving inhalation of carbon monoxide from burning charcoal, a notable suicide method in East Asia.

- 5.

Firearms or explosives (E955): Self-inflicted injury caused by firearms (e.g., guns) or explosive devices.

- 6.

Hanging, strangulation, or suffocation (E953): Self-inflicted asphyxiation, including hanging or suffocation.

- 7.

Intentional self-harm by cutting or piercing (E956): Use of sharp objects such as knives, razors, or broken glass to cause self-injury.

- 8.

Drowning and submersion (E954): Suicide attempts involving immersion in water or other liquids leading to suffocation.

This classification aligns with international medical coding systems, ensuring consistency in defining and analyzing suicide methods across different datasets.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- 1.

Data cleaning and processing: Cases with missing essential information, such as hospitalization dates, age, or suicide attempt details, were excluded to ensure data accuracy and consistency. Duplicate records of the same hospitalization event were removed to prevent overestimation.

- 2.

Descriptive statistics: Percentages and frequency distributions were computed for demographic characteristics, suicide methods, and hospitalization data. Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages.

- 3.

Calculation of the hospitalization rate: The crude hospitalization rate was computed by dividing the total number of suicide-related hospitalizations each year by the total population of Taiwan in the corresponding year. The results were expressed per 100,000 people.

- 4.

Calculation of the prevalence rate: The prevalence of suicide-related hospitalizations was calculated as the number of individuals who were hospitalized for self-harm per year divided by the total population. This measure was presented per 100,000 people annually [8–11].

- 5.

Case fatality rate among hospitalized patients: The proportion of suicide-related deaths occurring among hospitalized individuals was determined by dividing the number of in-hospital suicide fatalities by the total number of suicide-related hospitalizations, with results expressed as a percentage of total cases.

- 6.

Joinpoint regression analysis for trend detection: Joinpoint regression analysis was used to assess changes in suicide hospitalization rates over time. The analysis was performed using the joinpoint regression program (Version X.X, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA). The model was designed to detect statistically significant joinpoints or time points at which trends changed direction or magnitude, while minimizing the number of segments. The annual percentage change (APC) and the average annual percentage change (AAPC) were calculated for different time intervals. Statistical significance was determined using Monte Carlo permutation tests, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed to assess the precision of trend estimates [12–14] (Table S1-S2, Figure S1).

By applying these statistical methods, this study aimed to comprehensively evaluate the trends, demographic characteristics, and method-specific hospitalization rates for suicide attempts in Taiwan over the study period.

3. Results

This study aimed to analyze the demographic, regional, and temporal trends in suicide hospitalization rates and the distribution of suicide methods to identify high-risk populations and regions.

3.1. Suicide Hospitalization Rate and Regional Distribution

Among the 66,399 suicide inpatients, 55.01% were female, which was 1.22 times higher than males (44.99%). The age distribution was predominantly concentrated in the 20–39 age group (46.63%). The top three cities with the highest absolute number of suicide hospitalizations were Taichung City (16.47%), Kaohsiung City (13.06%), and Taipei City (12.05%). However, after adjusting for the population, the highest hospitalization rates were observed in Chiayi City (37.67 per 100,000), Yilan County (34.62 per 100,000), and Taichung City (21.84 per 100,000) (Table 1).

| Suicide (overall) | Solid-liquid | Jumping from a building | Charcoal burning | Hanging | Gas | Cut-through tool | Drowning | Firearms | Other and later effects | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | Number of people | Rate | |

| Total | 66,399 | 15.19 | 41,663 | 9.53 | 12,700 | 2.9 | 5497 | 1.26 | 1440 | 0.33 | 653 | 0.15 | 558 | 0.13 | 20 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3864 | 0.88 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 29,874 | 13.55 | 17,125 | 7.77 | 5767 | 2.62 | 3115 | 1.41 | 852 | 0.39 | 271 | 0.12 | 225 | 0.1 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2509 | 1.14 |

| Female | 36,525 | 16.85 | 24,538 | 11.32 | 6933 | 3.2 | 2382 | 1.1 | 588 | 0.27 | 382 | 0.18 | 333 | 0.15 | 14 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 1355 | 0.62 |

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 10–14 | 367 | 1.33 | 210 | 0.76 | 72 | 0.26 | 21 | 0.08 | 14 | 0.05 | 4 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 0.16 |

| 15–19 | 3544 | 11.64 | 1966 | 6.46 | 1058 | 3.48 | 182 | 0.6 | 54 | 0.18 | 45 | 0.15 | 14 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 225 | 0.74 |

| 20–24 | 7741 | 23.43 | 4400 | 13.32 | 2121 | 6.42 | 614 | 1.86 | 72 | 0.22 | 88 | 0.27 | 32 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 413 | 1.25 |

| 25–29 | 8254 | 24.01 | 4605 | 13.39 | 2041 | 5.94 | 909 | 2.64 | 110 | 0.32 | 84 | 0.24 | 56 | 0.16 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0.01 | 445 | 1.29 |

| 30–34 | 7771 | 21.7 | 4335 | 12.11 | 1773 | 4.95 | 873 | 2.44 | 119 | 0.33 | 93 | 0.26 | 71 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 504 | 1.41 |

| 35–39 | 7196 | 19.84 | 4320 | 11.91 | 1375 | 3.79 | 807 | 2.23 | 116 | 0.32 | 77 | 0.21 | 61 | 0.17 | 3 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 437 | 1.2 |

| 40–44 | 6479 | 18.29 | 4073 | 11.49 | 1194 | 3.37 | 683 | 1.93 | 127 | 0.36 | 74 | 0.21 | 47 | 0.13 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 279 | 0.79 |

| 45–49 | 5307 | 15.42 | 3431 | 9.97 | 798 | 2.32 | 537 | 1.56 | 162 | 0.47 | 42 | 0.12 | 52 | 0.15 | 2 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 283 | 0.82 |

| 50–54 | 3894 | 12.46 | 2558 | 8.19 | 479 | 1.53 | 384 | 1.23 | 114 | 0.36 | 35 | 0.11 | 53 | 0.17 | 3 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 268 | 0.86 |

| 55–59 | 3005 | 11.73 | 2054 | 8.02 | 355 | 1.39 | 223 | 0.87 | 108 | 0.42 | 26 | 0.1 | 49 | 0.19 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 189 | 0.74 |

| 60–64 | 2734 | 13.53 | 2045 | 10.12 | 312 | 1.54 | 95 | 0.47 | 90 | 0.45 | 20 | 0.1 | 37 | 0.18 | 5 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 130 | 0.64 |

| 65–69 | 2648 | 17.36 | 2026 | 13.28 | 278 | 1.82 | 62 | 0.41 | 93 | 0.61 | 25 | 0.16 | 19 | 0.12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 145 | 0.95 |

| 70–74 | 2499 | 20.79 | 1953 | 16.24 | 287 | 2.39 | 25 | 0.21 | 85 | 0.71 | 16 | 0.13 | 21 | 0.17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 0.93 |

| 75–79 | 2345 | 25.09 | 1774 | 18.98 | 281 | 3.01 | 41 | 0.44 | 78 | 0.83 | 12 | 0.13 | 24 | 0.26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 135 | 1.44 |

| 80–84 | 1631 | 27.09 | 1213 | 20.15 | 204 | 3.39 | 16 | 0.27 | 57 | 0.95 | 9 | 0.15 | 20 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 | 1.86 |

| ≧ 85 | 984 | 22.81 | 700 | 16.23 | 72 | 1.67 | 25 | 0.58 | 41 | 0.95 | 3 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 143 | 3.31 |

| Region | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Taipei City | 8001 | 15.89 | 4818 | 9.57 | 1525 | 3.03 | 849 | 1.69 | 195 | 0.39 | 108 | 0.21 | 57 | 0.11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 447 | 0.89 |

| New Taipei City | 5378 | 7.46 | 2651 | 3.68 | 1709 | 2.37 | 466 | 0.65 | 153 | 0.21 | 31 | 0.04 | 66 | 0.09 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 300 | 0.42 |

| Taoyuan City | 4606 | 12.3 | 2593 | 6.93 | 1177 | 3.14 | 291 | 0.78 | 84 | 0.22 | 128 | 0.34 | 35 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 297 | 0.79 |

| Taichung City | 10,936 | 21.84 | 7059 | 14.1 | 1803 | 3.6 | 1258 | 2.51 | 203 | 0.41 | 71 | 0.14 | 41 | 0.08 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 499 | 1 |

| Tainan City | 7342 | 20.65 | 4669 | 13.13 | 1309 | 3.68 | 632 | 1.78 | 167 | 0.47 | 30 | 0.08 | 113 | 0.32 | 4 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 418 | 1.18 |

| Kaohsiung City | 8675 | 16.52 | 5240 | 9.98 | 1723 | 3.28 | 732 | 1.39 | 142 | 0.27 | 86 | 0.16 | 103 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.01 | 1 | 0 | 645 | 1.23 |

| Changhua County | 5116 | 20.65 | 3666 | 14.79 | 641 | 2.59 | 320 | 1.29 | 103 | 0.42 | 4 | 0.02 | 12 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 370 | 1.49 |

| Chiayi County | 1203 | 11.69 | 889 | 8.64 | 142 | 1.38 | 75 | 0.73 | 22 | 0.21 | 12 | 0.12 | 5 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 58 | 0.56 |

| Yilan County | 3029 | 34.62 | 2250 | 25.72 | 369 | 4.22 | 217 | 2.48 | 48 | 0.55 | 20 | 0.23 | 14 | 0.16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 111 | 1.27 |

| Hualien County | 1314 | 20.29 | 636 | 9.82 | 431 | 6.66 | 57 | 0.88 | 27 | 0.42 | 16 | 0.25 | 9 | 0.14 | 6 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 132 | 2.04 |

| Chiayi City | 1937 | 37.67 | 1207 | 23.47 | 392 | 7.62 | 156 | 3.03 | 53 | 1.03 | 11 | 0.21 | 17 | 0.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 101 | 1.96 |

| Lienchiang County | 18 | 9.03 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.01 | 3 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3.51 |

- Note: 1. Rate definition: The rate represents the number of cases per 100,000 individuals per year. 2. The overall suicide rate (15.19) was calculated by dividing the number of suicide cases by the total population and then multiplying by 100,000. 3. These rates are based on annual population statistics and represent average annual incidence rates between 2000 and 2018, rather than a direct conversion of cumulative case numbers.

3.2. Hospitalization Rate by the Suicide Method

Among the 66,399 suicide-related hospitalizations, the most common method was poisoning by solids and liquids (41,663 cases, 62.75%), followed by jumping from buildings (12,700 cases, 19.13%) and charcoal burning (5497 cases, 8.28%). Other suicide methods included injuries classified under “other and late effects” (3863 cases, 5.82%), hanging (1439 cases, 2.17%), gas poisoning (648 cases, 0.98%), cutting or piercing instruments (555 cases, 0.84%), drowning (22 cases, 0.03%), and firearms (11 cases, 0.01%) (Table 1). The term “other and late effects” refers to residual categories in the ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM coding system used in hospitalization records. These codes typically include delayed complications of self-injury or cases that do not fit neatly into other predefined categories. For this study, suicide methods were categorized based on primary diagnosis and external cause codes (E-codes) as recorded in the NHIRD. “Other and late effects” include ICD-9-CM codes such as E959 and similar categories that capture sequelae or less common methods (Table 1).

3.3. Gender Distribution of Suicide Methods

When stratified by gender, females accounted for a higher percentage of suicide-related hospitalizations involving drowning (70.00%), cutting tools (59.68%), solids and liquids (58.90%), gas poisoning (58.50%), and jumping from buildings (54.59%). Conversely, males accounted for a higher percentage of cases involving hanging (59.17%) and charcoal burning (56.17%) (Table 1).

3.4. Age Distribution of Suicide Methods

The methods of suicide showed notable variation across different age groups. Among individuals aged 25–29 years, the most frequently used methods were poisoning by solid and liquid substances (accounting for 11.05% of cases in this group), charcoal burning (16.54%), and, notably, gunshot injuries, which, while rare overall, comprised 75.00% of suicide hospitalizations in this age bracket. In the 30–34 age group, gas poisoning (14.24%) and the use of cutting tools (12.72%) were more common compared to other age cohorts. Hanging was most prevalent among those aged 45–49 years, comprising 11.25% of cases, whereas drowning was more frequently observed among individuals aged 60–64 years, making up 25.00% of hospitalizations for suicide in that age range.

After adjusting for the population size, the highest age-specific hospitalization rates for particular methods were identified in several groups. Individuals aged 20–24 years had the highest rates of jumping from buildings (6.42 per 100,000) and gas poisoning (0.27 per 100,000). Those aged 25–29 years exhibited the highest rate of charcoal burning at 2.64 per 100,000. Meanwhile, among individuals aged 80–84 years, solid-liquid poisoning reached a peak hospitalization rate of 20.15 per 100,000, with hanging and use of cutting tools also highest in this age group at 0.95 and 0.33 per 100,000, respectively (Table 1).

3.5. Hospitalization and Mortality

The incidence, prevalence, and mortality of suicide-related hospitalizations are shown in Table 2. In this study, the “hospitalization incidence” was defined as the number of first-time hospitalizations for suicidal behavior per 100,000 people each year, and the “hospitalization prevalence” was defined as the total number of hospitalizations for suicidal behavior per 100,000 people each year, including repeat hospitalizations. The term “hospital mortality rate” refers to the proportion of hospitalized patients who committed suicide and ultimately died. The specific definition of this term is provided in the Methods section and in the footnote to Table 2.

| Year | Number of deaths | Mortality rate (per 100,000) | Number of inpatients | Hospitalization incidence rate (per 100,000) | Number of hospitalizations | Hospitalization prevalence rate (per 100,000) | Percentage of fatalities (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2177 | 9.97 | 1940 | 8.88 | 6789 | 31.09 | 52.88 |

| 1999 | 2281 | 10.36 | 2582 | 11.73 | 7805 | 35.46 | 46.91 |

| 2000 | 2471 | 11.14 | 3005 | 13.55 | 8976 | 40.46 | 45.12 |

| 2001 | 2781 | 12.45 | 3240 | 14.5 | 9795 | 43.84 | 46.19 |

| 2002 | 3053 | 13.59 | 3260 | 14.51 | 9865 | 43.92 | 48.36 |

| 2003 | 3195 | 14.16 | 3378 | 14.97 | 9972 | 44.2 | 48.61 |

| 2004 | 3468 | 15.31 | 3343 | 14.76 | 10,021 | 44.25 | 50.92 |

| 2005 | 4282 | 18.84 | 3367 | 14.81 | 9853 | 43.35 | 55.98 |

| 2006 | 4406 | 19.3 | 3245 | 14.22 | 9352 | 40.98 | 57.59 |

| 2007 | 3933 | 17.16 | 2923 | 12.75 | 8711 | 38.01 | 57.37 |

| 2008 | 4128 | 17.95 | 2735 | 11.89 | 8345 | 36.29 | 60.15 |

| 2009 | 4063 | 17.61 | 2669 | 11.56 | 8185 | 35.47 | 60.35 |

| 2010 | 3889 | 16.81 | 2505 | 10.82 | 7986 | 34.51 | 60.82 |

| 2011 | 3507 | 15.12 | 2709 | 11.68 | 8372 | 36.1 | 56.42 |

| 2012 | 3766 | 16.18 | 2452 | 10.54 | 8533 | 36.67 | 60.57 |

| 2013 | 3565 | 15.27 | 2844 | 12.18 | 9096 | 38.96 | 55.62 |

| 2014 | 3542 | 15.13 | 3647 | 15.58 | 9783 | 41.8 | 49.27 |

| 2015 | 3675 | 15.66 | 3824 | 16.3 | 10,124 | 43.15 | 49.01 |

| 2016 | 3765 | 16.01 | 3978 | 16.92 | 10,897 | 46.34 | 48.62 |

| 2017 | 3871 | 16.43 | 4256 | 18.07 | 11,145 | 47.31 | 47.63 |

| 2018 | 3865 | 16.39 | 4497 | 19.07 | 11,743 | 49.8 | 46.22 |

| 2019 | 3864 | 16.38 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 2020 | 3656 | 15.5 | — | — | — | — | — |

- Note: Mortality rate: The number of suicide deaths per 100,000 people in the population. Incidence rate (hospitalization rate): The number of hospital admissions due to suicide attempts per 100,000 people. Prevalence rate: The total number of hospitalizations for suicide attempts (including repeat cases) per 100,000 people. Percentage of fatalities: The proportion of hospitalized suicide attempts that resulted in death. Unlike the mortality rate, which considers the entire population, this measure focuses only on those who were admitted to hospitals.

During the study period, it was observed that the prevalence of suicide hospitalizations was significantly higher than the incidence, indicating that some patients had been hospitalized multiple times, which may reflect a tendency towards recurrent suicidal behavior or be related to underlying mental health problems and long-term chronic stress. This phenomenon indicates that long-term tracking and mental health intervention for high-risk groups are areas that need to be strengthened urgently.

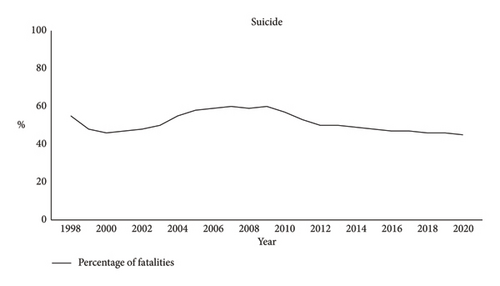

3.6. Changes in Suicide Trends (Suicide Incidence/Hospitalization Rate)

From 1998 to 2020, the overall suicide mortality rate increased by 55.47%, from 9.97 per 100,000 to 15.50 per 100,000. The incidence rate (hospitalization rate) rose by 114.75%, from 8.88 per 100,000 to 19.07 per 100,000. The prevalence rate increased by 60.18%, from 31.09 per 100,000 to 49.80 per 100,000, while the percentage of deaths due to hospitalization decreased by 12.59%, from 52.88% to 46.22% (Table 2, Figures 1 and 2).

According to the WHO definition, suicide is recognized only among individuals aged 10 years and above, as suicidal thoughts or intentions are not applicable to younger children. Therefore, cases of children under 10 years old who die by intentional harm are classified as homicides rather than suicides. Further analysis of suicides among individuals aged 10 years and older revealed a 44.95% increase in the suicide mortality rate, from 11.68 per 100,000 to 16.93 per 100,000, between 1998 and 2020. Data from the National Statistics File (1998–2020) indicated that the incidence rate (hospitalization rate) increased by 100.38%, from 10.41 per 100,000 to 20.86 per 100,000, and the prevalence rate rose by 49.53%, from 36.42 per 100,000 to 54.46 per 100,000 (Table 2).

- •

Deaths occur during hospitalization.

- •

Deaths among those who were hospitalized.

- •

Hospital case fatality rate—the percentage of hospitalized suicide attempt cases that resulted in death.

From the above results, the overall increase in suicide mortality, incidence, and prevalence rates in Taiwan was 10.52%, 14.37%, and 106.5%, respectively (Table 2, Figure 1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Age Differences in Suicide Hospitalization Rates

Our study found that the highest rate of suicide hospitalization occurred among individuals aged 20–39 years (46.63%). This finding aligns with studies conducted in Iran, where the average age of suicide was 26.8 years, and the highest rates of suicide attempts were reported in the 15–24 and 25–34 age groups (48% and 32.5%, respectively) [15]. Similarly, a study in Panama (2007–2016) reported that individuals aged 20–29 years had the highest suicide mortality rate (47%) [16]. The elevated suicide rates among young people may be attributed to life stressors, such as job instability, financial difficulties, relationship problems, and social pressures. For instance, young individuals often face challenges in building careers, achieving educational goals, or meeting family expectations, which can lead to feelings of hopelessness and suicidal behavior [17]. In contrast, studies from Japan and Hong Kong have reported higher suicide mortality rates among middle-aged and elderly individuals [18, 19]. This discrepancy may be influenced by sociocultural differences. In aging societies such as Japan, older adults may experience greater social isolation, chronic health conditions, and economic disadvantages, all of which increase their suicide risk [20–22]. These findings indicate that age-related suicide risk is strongly associated with socioeconomic and cultural factors, which vary significantly across regions [20–22].

4.2. Gender Differences in Suicide Hospitalization Rates

This study found that females had a higher rate of hospitalization for suicide than males (55% vs. 45%). This finding aligns with previous studies conducted in Taiwan, which reported a higher frequency of hospitalization for suicide attempts among women from 1998 to 2015 [23]. Similarly, a multinational study spanning Asia, Europe, and the Americas found that young women had higher rates of suicide attempts compared to men [24]. Despite this, suicide mortality rates remain higher among men. For instance, in the United States, between 1999 and 2017, male adolescents aged 10–19 years were three to four times more likely to die by suicide than their female counterparts [25–27]. This difference is largely attributable to the methods used: men are more likely to choose highly lethal methods, such as hanging and firearms, whereas women more often use less lethal methods, such as poisoning or overdose [28].

Gender differences in suicidal behavior may be influenced by social and cultural norms. In Taiwanese society, women are more likely to express emotional distress and seek help, which may increase the number of nonfatal suicide attempts and subsequent hospitalizations. Conversely, cultural expectations of masculinity often discourage men from expressing emotions, which can lead to the use of more violent and lethal methods of suicide [28–30]. Moreover, studies have shown that Taiwanese women have a higher prevalence of mental health conditions, such as depression, which increases their risk of suicide attempts [26, 27]. While men report fewer mental health symptoms, they tend to exhibit higher impulsivity and stronger death intent, contributing to their higher suicide mortality rates [31–38].

In addition to social and cultural factors, biological and psychological factors may also contribute to the observed gender differences. Biologically, studies have shown that hormonal fluctuations in women, such as variations in estrogen and progesterone levels, can affect emotional regulation, making them more susceptible to depression and anxiety, which in turn increases the risk of suicide attempts [39, 40]. In contrast, testosterone levels in men have been associated with impulsivity and aggressive behavior, potentially leading them to engage in more aggressive actions under stress, including the selection of highly lethal suicide methods [41, 42].

On a psychological level, women are more likely to adopt internalizing coping strategies in response to stress, such as self-blame and rumination, which may contribute to higher suicide attempt rates [43, 44]. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to engage in externalizing coping strategies, such as impulsive behaviors and substance use, which can increase the risk of suicide mortality [45, 46].

These findings underscore the importance of implementing gender-sensitive suicide prevention strategies. For women, early detection of mental health issues and timely intervention are crucial in reducing suicide attempt rates. For men, reducing the stigma surrounding emotional vulnerability and controlling access to highly lethal suicide methods could significantly lower suicide mortality rates.

4.3. Regional Differences in Suicide Hospitalization Rates

Our study found that Taichung City (16.47%), Kaohsiung City (13.06%), and Taipei City (12.05%) were the areas with the highest suicide hospitalization rates. Suicide rates may be higher in these urban areas due to factors such as high population density, increased stress from competitive job markets, and greater access to medical facilities capable of treating suicide attempts. In contrast, studies from South Korea and other countries have often reported higher suicide mortality rates in rural areas [31]. This disparity may result from limited access to mental health services in rural regions, leading to lower hospitalization rates but higher mortality rates [32]. Additionally, rural residents frequently experience social isolation, economic hardship, and limited resources, all of which may exacerbate suicide risk [33].

In urban areas, although individuals have better access to healthcare, the stresses of urban living may contribute to increased hospitalization rates [34]. Specifically, in Taiwan, high housing prices in major cities can create financial strain, especially for young adults and low-income families, leading to long-term financial insecurity and psychological distress [35]. The intense work culture, characterized by long working hours, high job competition, and job instability can contribute to chronic stress, burnout, and feelings of helplessness [36]. Additionally, social isolation in densely populated cities, where traditional community ties are weaker, may lead to loneliness and a lack of emotional support [37].

Moreover, the fast-paced nature of urban life, coupled with exposure to air pollution, noise pollution, and crowded living conditions, may contribute to heightened stress levels and poor mental health outcomes [38]. Access to lethal means, such as high-rise buildings and certain medications, may further elevate the risk of suicide attempts [47]. These environmental and occupational stressors suggest that while urban residents have better access to healthcare, the pressure of city life itself may increase their vulnerability to suicide attempts and hospitalizations [48].

These findings highlight the need for region-specific suicide prevention strategies. In urban areas, policies aimed at improving work-life balance, increasing access to affordable housing, and fostering social support could help mitigate stressors contributing to suicide risk [49]. Additionally, enhancing mental health services and ensuring their accessibility within both urban and rural areas would be crucial in reducing overall suicide hospitalization rates [50–54].

4.4. Differences in Suicide Methods

Our study also found that suicide methods varied by gender and region. Women were more likely to use solid or liquid substances, gas, drowning, and jumping, while men primarily used charcoal burning and hanging. These findings are consistent with studies in Korea, Japan, and other Asian countries, which have reported similar gender-based differences in suicide methods [28, 49–51]. The choice of the suicide method is often influenced by availability and cultural factors. For example, the widespread use of pesticides in agricultural regions has made poisoning a common method in rural Asia [27, 52]. Conversely, the high urbanization rate in cities such as Taipei may lead to a higher prevalence of suicide by jumping, given the abundance of high-rise buildings [53, 54].

Cultural attitudes toward death and body image also play a significant role. Women may avoid highly disfiguring methods due to societal pressures surrounding physical appearance, whereas men may choose methods perceived as quick and decisive, reflecting traditional notions of masculinity [55, 56]. These findings underscore the importance of region- and culture-specific suicide prevention strategies. Tailoring prevention efforts to address the unique social, cultural, and environmental factors influencing suicide methods can help mitigate risks and save lives [57, 58].

4.5. Factors Influencing the Changing Trend of Suicide Hospitalization

Over the past decade, Taiwan’s suicide hospitalization rate has increased dramatically, by 100.38%. In contrast, the global suicide rate decreased by 33% between 1990 and 2016, from 16.6 to 11.2 per 100,000 people [4]. However, during the same period (2000–2016), the suicide rate in the United States increased by 35% [59].

Research indicates that the suicide rate among Taiwanese teenage girls increased annually between 2009 and 2015 [7]. According to 2019 statistics from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, suicide was the second leading cause of death among Taiwanese adolescents, accounting for 12.5% of all deaths—second only to accidental injuries (41.9%) and tied with malignant tumors [60]. The main causes of adolescent suicide are closely linked to “emotional and interpersonal relationship problems,” “depression and mental health issues,” and “school-related problems,” highlighting the critical role of schools in promoting suicide prevention [61].

Long-term changes in suicide rates are primarily driven by economic recessions, which tend to increase suicide rates. Between 1959 and 2007, every 1% increase in Taiwan’s unemployment rate was associated with a 3.1% increase in the male suicide rate [62]. Additionally, the introduction of new suicide methods (e.g., pesticide ingestion and jumping from tall buildings) has contributed to fluctuations in suicide rates in some Asian countries. For example, the suicide rate in Hong Kong increased by 23% between 1998 and 2002, rising from 13.3 to 16.4 per 100,000 people, while the suicide rate in Taiwan increased by 39% during the same period, from 8.9 to 12.4 per 100,000 people [54]. Divorce rates have also been identified as a factor influencing suicide risk. Studies show that divorced individuals in Asian countries face a higher risk of suicide than their married counterparts [63, 64]. According to statistics from Taiwan’s Ministry of the Interior, the divorce rate in Taiwan increased from 2.28 to 2.31 per 1000 people between 2015 and 2017 [65], a trend that may have contributed to the observed rise in suicide rates.

4.6. The Impact of Pain on Mental Health and Suicide During COVID-19

The global outbreak of COVID-19 prompted many countries to implement unprecedented physical distancing measures to curb the spread of the virus and reduce the burden on healthcare systems. These measures often included national lockdowns, quarantine, reduced social contact, and restrictions on movement. There is substantial evidence that these restrictions, combined with heightened fear of severe illness, loneliness, financial difficulties, and uncertainty about the pandemic’s trajectory, have had profound adverse effects on mental health [11].

Mental distress, also referred to as “psychache” [66], is defined as an acute state of intense psychological pain characterized by negative cognitive and emotional self-perceptions, such as feelings of inadequacy, guilt, and distress. This condition is often accompanied by fear, anxiety, loneliness, and helplessness, alongside a sense of disconnection, loss, or incompleteness of the self [67]. Mental distress is thought to arise from discrepancies between one’s ideal and actual self-perceptions, coupled with an awareness of personal responsibility in the experience of emotional pain [67]. Over time, research has increasingly emphasized the transdiagnostic nature of mental distress, identifying it as a risk factor for various psychiatric disorders and the most critical predictor of suicide risk, surpassing depression. Mental distress is also considered a key predictor of disease progression in psychiatric conditions [68]. Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, suicide risk is expected to increase both in the short and long term due to widespread and prolonged economic, social, health, and psychological vulnerabilities [69, 70]. Several major studies have reported an overall increase in rates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide mortality during the pandemic compared with prepandemic periods [71–73].

4.7. Implications of Suicide Hospitalization Incidence and Prevalence Trends

In this study, we observed a consistent increase in the suicide-related hospitalization incidence and prevalence rates over the study period. Notably, the prevalence of suicide-related hospitalizations substantially exceeded the incidence. This discrepancy suggests that a significant proportion of patients were hospitalized more than once for suicide attempts, indicating a pattern of repeated suicidal behavior. This finding has important clinical and public health implications, underscoring the need for long-term monitoring and follow-up of individuals who have previously attempted suicide.

The observation that prevalence rates exceed incidence rates is particularly concerning, as it implies that many individuals experience recurrent self-harm episodes requiring hospitalization. Previous studies have established that individuals with a history of suicide attempts are at significantly increased risk for subsequent attempts and suicide mortality. Therefore, comprehensive postdischarge care—including psychiatric evaluation, long-term outpatient treatment, and community-based mental health support—should be prioritized for this high-risk group.

In the context of this study, the term “hospitalization rate” refers specifically to suicide-related hospitalizations, not general admissions. Clarifying this definition is crucial to ensure accurate interpretation of the results and meaningful comparison with other national or international datasets.

4.8. Research Strengths

This study has several notable strengths. First, it utilizes a large-scale, nationwide dataset that covers nearly 2 decades of hospitalization data, allowing for robust trend analysis and age- and gender-stratified subgroup comparisons. Second, by including both incidence and prevalence rates, the study provides a more nuanced understanding of the burden of suicide-related hospitalizations. Finally, the use of medically certified hospitalization records—as opposed to self-reported data—significantly reduces recall bias and enhances the reliability and validity of suicide attempt classification.

Given the observed increase in both incidence and prevalence, healthcare systems should adopt proactive strategies for suicide prevention. These include early detection of at-risk individuals, continuity of mental healthcare after discharge, and the development of targeted interventions aimed at reducing repeated suicide attempts. Policies that integrate school-based programs, community support networks, and accessible mental health resources will be essential in mitigating the growing burden of suicide-related hospitalizations.

4.9. Research Limitations

The primary strength of this study lies in its longitudinal analysis of the entire population in Taiwan. Additionally, the mode of suicide was determined by physician or forensic prescription diagnosis, which reduces the risk of recall bias often observed in retrospective or survey-based studies and enhances the validity of the data. However, this study has several limitations. First, information on lifestyle habits (e.g., alcohol and tobacco consumption), family and medical history, socioeconomic status, and blood biochemical values were not available. Second, suicide cases were identified using E-codes, which are recorded only in inpatient files and not in outpatient or emergency files. This limitation may have led to an underestimation of the number of cases and overall healthcare utilization. Third, patients who died immediately after a suicide attempt and those not hospitalized due to minor injuries were excluded from the study.

- •

Data source variability: This study is based on hospitalization records, which may not capture all suicide attempts, particularly those that did not result in hospital admission. In contrast, the Taiwan Suicide Prevention Center may use a broader dataset, including forensic reports, emergency department visits, and police records.

- •

Differences in classification methods: This study categorizes suicide methods based on hospitalization diagnoses, which may differ from the classification criteria used by the Taiwan Suicide Prevention Center. Cases involving multiple methods (e.g., self-poisoning combined with cutting) may be classified differently depending on the primary recorded cause.

- •

Time frame and population considerations: This study covers the period from 2000 to 2018, while the Taiwan Suicide Prevention Center may use more recent statistics or different aggregation methods. Population changes over time, shifts in suicide methods, and prevention policies could influence ranking differences.

- •

Hospitalization vs. fatality rates: The ranking of suicide methods in this study reflects hospitalization rates rather than fatality rates. Some methods, such as hanging, may have a higher lethality but result in fewer hospital admissions, whereas methods with higher survival rates, such as solid/liquid poisoning, may lead to more hospital-treated cases.

Further clarification of dataset definitions, inclusion criteria, and classification methodologies between sources is needed to reconcile these differences (Table 1).

5. Conclusion

Between 1998 and 2020, Taiwan experienced a significant rise in suicide-related hospitalizations and mortality rates, as demonstrated in Table 2 and Figure 1. This trend underscores the urgent need for targeted public health interventions. The increase in hospitalization rates suggests a growing severity or frequency of suicide attempts, emphasizing the necessity of strengthening early detection and intervention strategies.

Our findings highlight distinct gender- and age-related differences in suicide methods (Table 1), which should inform prevention efforts. Women, who more frequently attempted suicide via poisoning or cutting, may benefit from improved mental health support services and early intervention programs. Conversely, men and older adults, who tended to use highly lethal methods such as hanging or charcoal burning, require targeted strategies addressing underlying social, economic, and psychological risk factors.

Future research should explore the effectiveness of region-specific suicide prevention initiatives, given the disparities observed in hospitalization rates across different areas (Table 2). Additionally, further investigation into the long-term outcomes of hospitalized individuals, including recurrence rates and access to mental health care postdischarge, could provide valuable insights for policy and healthcare improvements.

To mitigate suicide risk, policymakers must implement a comprehensive, evidence-based approach combining mental health resources, crisis intervention, and community-based support systems. Public awareness campaigns tailored to high-risk demographics and expanded access to mental health services will be essential in addressing this growing concern and reducing suicide-related morbidity and mortality.

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted according to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). The Institutional Review Board of the Tri-Service General Hospital approved this study and waived the need for individual consent since all the identification data were encrypted in the NHIRD (TSGHIRB 1–105-05–142/TSGHIRB no. B202405024).

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

C.-H.C., Y.-C.H., P.-C.Y., H.-T.H., T.-H.W., C.-A.S., S.-H.H., R.-J.C., B.-L.W., W.-C.C., and N.-S.T.: conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data, critical review, and approval of the final version submitted for publication. C.-H.C., Y.-C.H., T.-H.W., C.-A.S., C.-T.T., L.-Y.F., W.-C.C., and N.-S.T.: statistical analysis, critical review, and approval of the final version submitted for publication. C.-H.C., Y.-C.H., T.-H.W., C.-A.S., W.-C.C., and N.-S.T.: drafting of the paper, critical review, and approval of the final version submitted for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. T.-H.W. and H.-T.H. contributed equally as first authors.

Funding

This study was funded by the Tri-Service General Hospital (grant numbers: TSGH-A-114010, TSGH-B-114022, and TSGH-D-114196).

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support from the Tri-Service General Hospital Research Foundation and the Medical Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Defense, Taiwan, ROC. They also appreciate the database provided by the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare (HWDC and MOHW).

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.