The Role of Place in Social Prescribing: A State-of-the-Art Literature Review

Abstract

Introduction: Social prescribing seeks to connect people to community-based resources, to improve their health and wellbeing. It is often framed as a response to health inequalities. However, the impact of place-based differences is seldom considered. As social prescribing depends on local resources, this is a significant knowledge gap. This review aims to examine the extent to which social prescribing research to date has engaged with places and communities.

Methods: This state-of-the-art literature review has three components: (1) Four databases (PubMed, ASSIA, Web of Science and Scopus) were searched for social prescribing literature reviews; key characteristics were charted and a timeline created. (2) Each review was assessed for its engagement with concepts of place, and findings were synthesised narratively. (3) Exploratory searches were conducted in PubMed for primary research on place in social prescribing, and findings summarised descriptively.

Results: A total of 97 eligible literature reviews were identified. A timeline of these reviews and their characteristics was created, including population, referral reasons, social prescribing model, intervention and aim. No reviews had ‘complete’ engagement with concepts of place. Thirty-one had ‘partial’ engagement. These suggested five ways of thinking about place: place as healing, experience of societal inequalities and its effect on place, how deprivation shapes place, place as the context for social prescribing and alternative conceptions of place. We found eight primary studies addressing social prescribing and place. Six looked in detail at a particular place or characteristic of places, and two contributed theoretical understandings of the relationship between place and social prescribing.

Discussion: The role of place in social prescribing remains understudied. Future research could develop theory and frameworks to account for place or identify which elements of place-based community infrastructure are particularly relevant for social prescribing, especially as deprivation and austerity continue to diminish community resources in the areas which most need them.

1. Introduction

Social prescribing refers to a range of practices in which people with unmet social or economic needs are connected to support within their communities, to help improve their health and wellbeing. A recent expert consensus study defined social prescribing as: ‘a means for trusted individuals in clinical and community settings to identify that a person has non-medical, health-related social needs, and to subsequently connect them to non-clinical supports and services within the community by co-producing a social prescription—a non-medical prescription to improve health and wellbeing and to strengthen community connections’ [1].

Across the United Kingdom, social prescribing takes place mostly in primary care settings. In Scotland, where the authors of this review are principally based, the dominant model of social prescribing involves community link workers, who are employed by third-sector organisations and based in General Practice. Community link workers typically work with people who have been referred by their General Practitioner (GP) or another primary healthcare professional, getting to know patients as individuals through a series of extended consultations and working together to develop a plan for community support [2, 3].

Social prescribing is a complex intervention: It is shaped by the needs of the patient; the knowledge and skills of the community link worker; and the availability of resources in the surrounding community which can be used to create a ‘social prescription’ [4]. However, while a growing body of research focusses on the characteristics and outcomes of patients or social prescribing models, less attention has been paid to the surrounding community, or how variations between places might affect social prescribing.

Austerity policies implemented across the United Kingdom since 2010 have had a major impact on the voluntary and community sector, as well as on public services, which are now considered ‘fragile’ due to prolonged under-funding [5]. The diminished quality and availability of public and community services and the impact of social security ‘welfare reform’ policies have been linked to worsening health outcomes [5, 6]. In Scotland, life expectancy fell by around two years from 2011 to 2019, but the impact was unequal—people in the 20% most deprived areas experienced a reduction of about 3.5 years [7].

Such inequality is a consistent companion of deprivation and austerity. The inverse care law is well-established in primary care: Communities with the greatest health needs typically have the least investment in primary health services [8]. It appears that the poorest communities in fact experience a ‘double inverse care law’, which also encompasses the community sector: More deprived areas typically have fewer voluntary and community resources in general [9, 10], and research suggests these are hit harder by cuts in government funding and support than community organisations in more affluent areas [11].

This poses a unique challenge for social prescribing. Social prescribing is often seen as most needed in communities that bear the brunt of deprivation; even if its ability to meaningfully challenge health inequalities remains contested [12]. In Scotland, the Scottish Government has actively prioritised investment in social prescribing in the country’s most deprived areas [13]. However, social prescribing needs access to a thriving voluntary and community sector to be as effective as possible [14, 15], and the voluntary and community sector in Scotland’s deprived areas has experienced the worst effects of ongoing financial constraints [11, 16].

These tensions suggest that it is essential to understand the impact of the specific places in which social prescribing is done. This could inform an understanding of the characteristics of neighbourhoods and communities which enable social prescribing to be effective, despite the challenges of austerity and deprivation. It could also enable a population-level understanding of unwarranted variation in community resources from place to place, and how this might affect the usefulness of social prescribing for people who live in those places.

1.1. Review Aim

The aim of this state-of-the-art literature review is to examine the extent to which social prescribing research to date has engaged with place and communities. Using literature reviews as milestones to mark out key developments and trends in academic thinking about social prescribing, it provides an overview of previous research directions and reflects on the scope for future research in this area.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

This review adopts the methodology for state-of-the-art literature reviews proposed by Barry et al. [17]. As such, it seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of social prescribing literature, reflecting on how researchers’ collective understanding and framing of the role of place in social prescribing has evolved; how past research framings and decisions have led us to our current understanding; and how we might build on that understanding, or re-engage with past directions, in order to take new research forward.

State-of-the-art literature reviews are informed by qualitative approaches to knowledge generation: recognising that past publications have been shaped by the disciplines and contexts of their authors, just as this review itself will be. As such, reflexivity is an integral part of our method [17]. Although this is not a systematic review, reporting of methods and findings is guided by the PRISMA 2020 statement where possible [18], to aid transparency and completeness (see Supporting Table S4). A review protocol was not registered prior to commencing this review.

2.2. Definitions

This review addresses the role of place in social prescribing research. Place itself is a broad concept, with a wide range of definitions, which generally combine elements of location and belonging [19]. For the purpose of this review, by ‘place’, we mean the specific physical locations in which social prescribing occurs, which might also be called communities or neighbourhoods.

Bagnall et al. [20] define ‘community infrastructure’ as public and ‘bumping’ spaces designed for people to meet and socialise; ‘third places’ (such as cafes, pubs, and libraries) which are used as social spaces; and the services that improve access to places—such as town planning, public art and public transport. We use an expanded version of this definition, also incorporating locally available community, voluntary and public services, in order to describe the features of a place, community or neighbourhood as a whole.

2.3. Stages 1–3: Research Question and Timeframe

The first stages of a state-of-the-art literature review involve defining a field of enquiry, establishing a timeframe and refining the research question in view of the timeframe chosen and any key milestones within that period [17].

The field of enquiry for this review is to explore how place, as the physical location of community resources and social support, is understood in the context of social prescribing research.

Although practices similar to social prescribing have a longer history, the term ‘social prescribing’ has entered common use in research and policy within the past 2 decades. A focus on social prescribing is therefore naturally self-limiting. A preliminary search on Google Scholar for papers with ‘social prescribing’ in the title found only one published between 1990 and 2000 [21], and a further 21 in the decade up to 2010. The first study mentioning ‘social prescribing’ in its title or abstract, indexed on the Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) database, dates from 2004 [22], and the first on PubMed dates from 2007 [23].

As such, no date limit was imposed on this review: All papers which address ‘social prescribing’ as a concept were potentially eligible for inclusion.

2.4. Stages 4-5: Searches, Selection and Analysis

We carried out a state-of-the-art literature review in three parts. First, we aimed to give an overview of trends in social prescribing research overall, as reflected in published literature reviews. Then, we identified and synthesised reviews addressing the role of place. To complement this, we conducted an exploratory search of primary research specific to place and social prescribing.

2.4.1. Overview of Social Prescribing Research Directions

To provide a general context for this review, we carried out a basic search on PubMed for the term ‘social prescribing’, in any field, on 7 March 2025. We recorded the number of hits per year, to describe publication trends over time (Section 3.1).

Our main search then focussed on published literature reviews specifically. Literature reviews are undertaken to synthesise current knowledge about a given question [18]. They may be used as a stepping stone to further research, by identifying gaps or uncertainties in the knowledge base, or to inform decision-makers about the direction and quality of evidence on a particular topic [24]. As such, literature reviews are useful indicators of the questions garnering research or policy attention in a given field.

We searched four academic databases, covering a range of disciplines, for literature reviews of any design: PubMed (health sciences), ASSIA (social sciences), Web of Science and Scopus (both with a broad overview of sciences and humanities).

The searches had two concept areas: terms related to social prescribing, which were sought in a limited number of fields (title or abstract in PubMed and Web of Science; title, abstract or keyword in Scopus; anywhere but full text in ASSIA), and terms related to literature reviews, which were sought in the title field only. Full details of the search strategy are provided in Supporting Table S1. Final searches were conducted on 25 February 2025. Protocols were followed up via searches on Google Scholar and protocol registers, to identify completed reviews.

Search results from all databases were combined in Endnote, deduplicated using the SR-Accelerator platform [25] and then imported into Covidence. Duplicates were identified and removed at each stage. Papers were screened by one reviewer, according to inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 1.

| Include | Exclude | |

|---|---|---|

| Phenomenon of interest | Social prescribing (in any form consistent with the definition by Muhl et al.) [1] | Not social prescribing |

| Study design | Peer-reviewed literature reviews/evidence syntheses—e.g., systematic reviews, scoping reviews, and narrative reviews | Primary studies |

| Commentaries or opinion pieces | ||

| Conference abstracts or posters | ||

| Grey literature | ||

| Published protocols for literature reviews, where no completed review is yet available | Published protocols for literature reviews, where a completed review is also available | |

| Format | Full text available in English | Languages other than English |

After screening, the remaining reviews were exported to Excel and a chart of key characteristics was developed for each paper [26], with extraction and charting done by one reviewer. The charted data included review characteristics (author, title, year published, review type, countries included); participant age group; reason for referral to social prescribing (health conditions, social determinants); social prescribing characteristics (social prescribing model, type of intervention referred to); health outcomes of interest; and study purpose. In general, key characteristics were extracted from the methods section of each review, in order to reflect the scope and intention of the review. However, the ‘country’ column was completed using the countries reported in the results section, rather than the inclusion criteria, of each review.

Initial detailed descriptions were refined into a set of codes (see Supporting Table S2) to allow rapid sorting and comparison of the papers within Excel. The papers were sorted chronologically within Excel to enable the development of a timeline of social prescribing research directions (Section 3.2). Review quality was not critically appraised, as the aim of this analysis was to describe the scope and directions of existing research, not to evaluate its strength.

2.4.2. ‘Place’ in Social Prescribing Literature Reviews

All papers included in the timeline of literature reviews were classed as having ‘complete’, ‘partial’ or ‘no’ direct relevance to this review’s primary focus on social prescribing and place. A literature review with ‘complete’ relevance was one that addressed the relationship between place and social prescribing as its primary objective. A review with ‘partial’ relevance was one that addressed place as part of its scope or findings, but not as a central focus.

Any paper with complete or partial relevance was read closely for familiarisation [17] and used to inform the analysis in Section 3.3. Common patterns were identified, and papers were grouped and analysed by theme.

2.4.3. Primary Research on Place and Social Prescribing

We carried out a set of exploratory scoping searches in PubMed to find primary research on social prescribing and place. The aim of this was to discover whether place was emerging as a focus in primary research, even if it was not being incorporated in literature reviews.

The searches combined ‘social prescribing’ with a set of terms related to place, detailed in Supporting Table S3. The search results were screened based on titles and abstracts, and relevant studies are summarised descriptively in Section 3.4.

2.5. Stage 6: Reflexivity

State-of-the-art literature reviews recognise that past and current research are shaped by researchers, who bring their own knowledge, values and perspectives to bear on their work [17]. Turning this lens on our own work, we reflect that this review will be shaped by our particular areas of expertise, our context and our sense of affiliation to others.

The lead author is completing this review as part of PhD research on social prescribing for people in mid- to later life. Although relatively new to this area of research, she has a background in health and social welfare policy and politics which informs a particular framing of the issues. The coauthors have an extensive track record of research on health systems or social policy in contexts of deprivation, and three coauthors are involved in various ongoing evaluations of social prescribing models.

The team are all based in Scotland and Northern England, so bring a particular familiarity with UK models of social prescribing, and UK policy contexts, which may lead to an overemphasis on UK-based challenges and trends as against those of other countries. All authors also have a track record of working closely with frontline health or social care professionals and voluntary sector organisations, which creates an unavoidable sense of affiliation and esteem for their work, and may make it difficult to engage fairly with evidence that challenges the value of what they do, but also approach this work as academic researchers practised in engaging critically with policy and practice narratives, including on social prescribing.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Social Prescribing Research

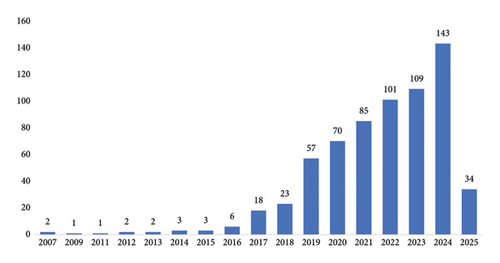

A simple PubMed search for ‘social prescribing’, as described in Section 2.4.1, returned 584 results. These follow a steep curve (see Figure 1): The first 100 papers were published over 12 years, from 2007 to 2019. By contrast, more than 100 papers per year were published from 2022 to 2024. This rate is likely to continue rising in 2025, with 34 new records from the first two months alone.

3.2. Timeline of Key Questions in Social Prescribing Research

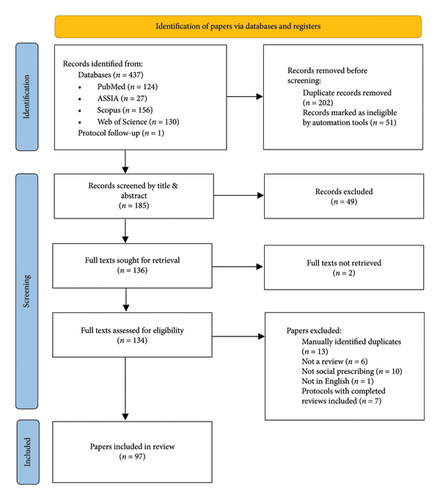

Searches for social prescribing literature reviews returned 438 records across four databases. This reduced to 236 papers after deduplication. After screening to exclude papers which did not focus on social prescribing or which were not literature reviews (n = 132), or protocols of published papers (n = 7), a total of 97 reviews were included. The screening process is summarised in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 2).

Key characteristics of the 97 included papers are summarised narratively here, and a full timeline of these reviews is set out in Table 2.

| Study characteristics | Age | Basis of referral | Type of social prescribing | Outcome | Purpose | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Title | Review type | Country | Age group | Health condition | Social determinant | Social prescribing model | Social prescribing intervention | Health outcome(s) | Study perspective |

| 2017 | ||||||||||

| Bickerdike et al. [27] | Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence | Systematic review | UK (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Service design |

| Jensen et al. [28] | Arts on prescription in Scandinavia: a review of current practice and future possibilities | Rapid review | HICs (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Arts and culture | ∗ | Specific SP intervention |

| Rempel et al. [29] | Preparing the prescription: A review of the aim and measurement of social referral programmes | Literature review | UK (majority) | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Defining social prescribing |

| 2018 | ||||||||||

| Chatterjee et al. [30] | Non-clinical community interventions: a systematised review of social prescribing schemes | ‘Systematised’ (not systematic) review | UK (all) | ∗ | Physical or mental health | ∗ | ∗ | Community-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Pescheny et al. [31] | Facilitators and barriers of implementing and delivering social prescribing services: A systematic review | Systematic review | UK (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Service design |

| 2019 | ||||||||||

| Leavell et al. [32] | Nature-based social prescribing in urban settings to improve social connectedness and mental well-being: a review | Literature review | USA (all) | Various ages | Loneliness | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Green or nature-based | Loneliness/connectedness | Specific SP intervention |

| 2020 | ||||||||||

| Elsden and Roe [33] | Does arts engagement and cultural participation impact depression outcomes in adults: a narrative descriptive systematic review of observational studies | Systematic review | ∗ | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | Arts and culture | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Howarth et al. [34] | What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: a scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription | Scoping review | HICs (majority) | ∗ | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | Green or nature-based | General health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Husk et al. [35] | What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review | Realist review | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Community-based | ∗ | Service design |

| Pescheny et al. [36] | The impact of social prescribing services on service users: A systematic review of the evidence | Systematic review | UK (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | General health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Tierney et al. [37] | Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: A realist review | Realist review | UK (all) | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Service design |

| 2021 | ||||||||||

| Burns et al. [38] | A systematic review of interventions to link families with preschool children from healthcare services to community-based support | Systematic review | UK or USA (majority) | Children and young people | ∗ | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Community-based | ∗ | Specific patient group |

| Calderón-Larrañaga et al. [39] | Tensions and opportunities in social prescribing. Developing a framework to facilitate its implementation and evaluation in primary care: a realist review | Realist review | ∗ | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Community-based | ∗ | Service design |

| Costa et al. [40] | Effectiveness of social prescribing programs in the primary health-care context: A systematic literature review | Systematic review | ∗ | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Community-based | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Impact on participants |

| Dingle et al. [41] | The effects of social group interventions for depression: Systematic review | Systematic review | ∗ | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | Community-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Lindsey et al. [42] | Social prescribing in community pharmacy: a systematic review and thematic synthesis | Systematic review | UK (majority) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | ∗ | Service design |

| McGrath et al. [43] | Effectiveness of community interventions for protecting and promoting the mental health of working-age adults experiencing financial uncertainty: A systematic review | Systematic review | HICs (all) | Adults | ∗ | Acute financial uncertainty | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Community-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Reinhardt et al. [44] | Understanding loneliness: a systematic review of the impact of social prescribing initiatives on loneliness | Systematic review | UK (all) | ∗ | Loneliness | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | Loneliness/connectedness | Impact on participants |

| Thomas et al. [45] | A systematic review to examine the evidence in developing social prescribing interventions that apply a co-productive, co-designed approach to improve well-being outcomes in a community setting | Systematic review | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | General health or wellbeing | Service design |

| Vidovic et al. [46] | Can social prescribing foster individual and community well-being? A systematic review of the evidence | Systematic review | UK (majority) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Loneliness/connectedness | Impact on participants |

| Zhang et al. [47] | Social prescribing for migrants in the United Kingdom: A systematic review and call for evidence | Systematic review | UK (all) | ∗ | ∗ | Migration | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Specific patient group |

| 2022 | ||||||||||

| Al-Khudairy et al. [48] | Evidence and methods required to evaluate the impact for patients who use social prescribing: a rapid systematic review and qualitative interviews | Rapid review | UK (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Impact on participants |

| Anderst et al. [49] | Screening and social prescribing in healthcare and social services to address housing issues among children and families: a systematic review | Systematic review | USA (majority) | Children and young people | ∗ | Housing issues | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Housing advice | ∗ | Service design |

| Araki et al. [50] | Social prescribing from the patient’s perspective: A literature review | Literature review | UK (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Impact on participants |

| Bild and Pachana [51] | Social prescribing: A narrative review of how community engagement can improve wellbeing in later life | Narrative review | ∗ | Older adults | Physical or mental health | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Community-based | General health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Blodgett et al. [52] | What works to improve wellbeing? A rapid systematic review of 223 interventions evaluated with the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scales | Rapid review | UK (all) | ∗ | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Mental health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Calderón-Larrañaga et al. [53] | What does the literature mean by social prescribing? A critical review using discourse analysis | Critical review + discourse analysis | ∗ | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Community-based | ∗ | Defining social prescribing |

| Cooper et al. [54] | Effectiveness and active ingredients of social prescribing interventions targeting mental health: A systematic review | Systematic review | UK (all) | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Community-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Dingle and Sharman [55] | Social prescribing: A review of the literature | Literature review | ∗ | ∗ | Loneliness | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | Loneliness/connectedness | Specific patient group |

| Elliott et al. [56] | Exploring how and why social prescribing evaluations work: A realist review | Realist review | UK (majority) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Community-based | ∗ | Evaluation |

| Featherstone et al. [57] | Health and wellbeing outcomes and social prescribing pathways in community-based support for autistic adults: A systematic mapping review of reviews | Mapping review | ∗ | Adults | Autism or neurodisability | ∗ | ∗ | Community-based | General health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Kiely et al. [58] | Effect of social prescribing link workers on health outcomes and costs for adults in primary care and community settings: a systematic review | Systematic review | ∗ | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | Mental health or wellbeing | Evaluation |

| Liebmann et al. [59] | Do people perceive benefits in the use of social prescribing to address loneliness and/or social isolation? A qualitative meta-synthesis of the literature | Systematic review | UK (majority) | ∗ | Loneliness | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Loneliness/connectedness | Impact on participants |

| Little et al. [60] | Promoting healthy food access and nutrition in primary care: A systematic scoping review of food prescription programs | Scoping review | USA (majority) | Various ages | ∗ | Food | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Food | Food access | Specific SP intervention |

| Nakagomi et al. [61] | Social determinants of hypertension in high-income countries: A narrative literature review and future directions | Narrative review | HICs (all) | ∗ | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Loneliness/connectedness | Specific patient group |

| Napierala et al. [62] | Social prescribing: Systematic review of the effectiveness of psychosocial community referral interventions in primary care | Systematic review | UK (majority) | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Psychosocial | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Specific SP intervention |

| Percival et al. [63] | Systematic review of social prescribing and older adults: Where to from here? | Systematic review | UK (majority) | Older adults | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Specific patient group |

| Rothe and Heiss [64] | Link workers, activities and target groups in social prescribing: a literature review: Managing community care | Literature review | UK (majority) | ∗ | Physical or mental health | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Psychosocial | ∗ | Service design |

| Sandhu et al. [65] | Intervention components of link worker social prescribing programmes: A scoping review | Scoping review | UK (all) | Adults | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | Unmet social needs (e.g., social isolation and housing instability) | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Community-based | Impact on person and system | Defining social prescribing |

| Thomas et al. [66] | Social prescribing of nature therapy for adults with mental illness living in the community: A scoping review of peer-reviewed international evidence | Scoping review | UK (majority) | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Green or nature-based | General health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Tierney et al. [67] | Tailoring cultural offers to meet the needs of older people during uncertain times: a rapid realist review | Rapid realist review | ∗ | Older adults | ∗ | ‘Conditions imposed by the pandemic’ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Arts and culture | General health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Tierney et al. [68] | The role of volunteering in supporting well-being—What might this mean for social prescribing? A best-fit framework synthesis of qualitative research | Framework synthesis | HICs (all) | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Volunteering | General health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Wang et al. [69] | Horticultural therapy for general health in the older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Systematic review | Other | Older adults | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Green or nature-based | General health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| 2023 | ||||||||||

| Alejandre et al. [70] | Contextual factors and programme theories associated with implementing blue prescription programmes: A systematic realist review | Realist review | UK or USA (majority) | Various ages | Physical or mental health | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Green or nature-based | General health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Bernard et al. [71] | Experiences of non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions for common mental health disorders in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups: A systematic review of qualitative studies | Systematic review | UK (majority) | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | Socioeconomic disadvantage | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | Mental health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Briggs et al. [72] | The effectiveness of group-based gardening interventions for improving wellbeing and reducing symptoms of mental ill-health in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis | Systematic review | ∗ | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | Green or nature-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Buechner et al. [73] | Community interventions for anxiety and depression in adults and young people: A systematic review | Systematic review | Other | Various ages | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | Community-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Cooper et al. [74] | Service user perspectives on social prescribing services for mental health in the United Kingdom: a systematic review | Systematic review | UK (all) | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Community-based | ∗ | Impact on participants |

| Davies et al. [75] | Enhancing student wellbeing through social prescribing: A rapid realist review | Rapid realist review | ∗ | Students | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | General health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Ebrahimoghli et al. [76] | Factors influencing social prescribing initiatives: a systematic review of qualitative evidence | Systematic review | UK (majority) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Service design |

| Gordon et al. [77] | Social prescribing for children and young people with neurodisability and their families initiated in a hospital setting: A systematic review | Systematic review | HICs (all) | Children and young people | Autism or neurodisability | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | General health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Grover et al. [78] | Older adults and social prescribing experience, outcomes, and processes: a meta-aggregation systematic review | Systematic review | HICs (all) | Older adults | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | General health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Hopkins et al. [79] | Beyond social prescribing: The use of social return on investment (SROI) analysis in integrated health and social care interventions in England and Wales: A protocol for a systematic review | Protocol for systematic review | UK (all) | Adults | Physical or mental health | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | General health or wellbeing | Evaluation |

| Htun et al. [80] | Effectiveness of social prescribing for chronic disease prevention in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials | Systematic review | ∗ | Adults | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Physical activity | General health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Linceviciute et al. [81] | Role of social prescribing link workers in supporting adults with physical and mental health long-term conditions: Integrative review | Integrative review | UK (majority) | Adults | Physical or mental health | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Service design |

| Muhl et al. [82] | Social prescribing and students: A scoping review protocol | Protocol for scoping review | ∗ | Students | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Specific patient group |

| Newstead et al. [83] | Speaking the same language: a scoping review to identify the terminology associated with social prescribing | Scoping review | UK (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | ∗ | ∗ | Defining social prescribing |

| Nguyen et al. [84] | Effect of nature prescriptions on cardiometabolic and mental health, and physical activity: a systematic review | Systematic review | HICs (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Green or nature-based | General health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Nichol et al. [85] | Exploring the effects of volunteering on the social, mental, and physical health and well-being of volunteers: An umbrella review | Umbrella review | USA (majority) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Volunteering | General health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Oster et al. [86] | Models of social prescribing to address non-medical needs in adults: a scoping review | Scoping review | HICs (all) | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | ∗ | Defining social prescribing |

| Paquet et al. [87] | Social prescription interventions addressing social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Meta-review integrating on-the-ground resources | Umbrella review | ∗ | Older adults | Loneliness | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Loneliness/connectedness | Specific patient group |

| Rapo et al. [88] | Critical components of social prescribing programmes with a focus on older adults—a systematic review | Systematic review | UK (majority) | Older adults | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | Loneliness/connectedness | Service design |

| Robinson et al. [89] | Examining psychosocial and economic barriers to green space access for racialised individuals and families: A narrative literature review of the evidence to date | Narrative review | UK or USA (all) | ∗ | ∗ | Racialised individuals/groups | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Green or nature-based | General health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Sonke et al. [90] | Social prescribing outcomes: a mapping review of the evidence from 13 countries to identify key common outcomes | Mapping review | HICs (majority) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | General health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Surugiu et al. [91] | Unveiling the presence of social prescribing in Romania in the context of sustainable healthcare: A scoping review | Scoping review | HICs (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | ∗ | Service design |

| Tanner et al. [92] | Non-pharmaceutical primary care interventions to improve mental health in deprived populations: a Systematic review | Systematic review | HICs (all) | ∗ | Mental health (primarily) | Socioeconomic disadvantage | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Teggart et al. [93] | Effectiveness of system navigation programs linking primary care with community-based health and social services: a systematic review | Systematic review | UK or USA (majority) | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | ∗ | Health service use | Impact on participants |

| 2024 | ||||||||||

| Ashe et al. [94] | Outcomes and instruments used in social prescribing: a modified umbrella review | Umbrella review | UK (majority) | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | ∗ | Evaluation |

| Baker et al. [95] | Australian link worker social prescribing programs: An integrative review | Integrative review | Australia (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Evaluation |

| Baker et al. [96] | ‘Eco-caring together’ pro-ecological group-based community interventions and mental wellbeing: a systematic scoping review | Scoping review | Other | ∗ | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | Green or nature-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Bos et al. [97] | Implement social prescribing successfully towards embedding: What works, for whom and in which context? A rapid realist review | Realist review | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | General health or wellbeing | Service design |

| Dash et al. [98] | Social prescribing for suicide prevention: a rapid review | Rapid review | ∗ | ∗ | Suicide risk | ∗ | ∗ | Community-based | Suicide prevention | Specific patient group |

| Dougherty et al. [99] | Coproduction in social prescribing initiatives: Protocol for a scoping review | Protocol for scoping review | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Unmet social needs (e.g., social isolation and housing instability) | May involve link worker or equivalent | ∗ | ∗ | Service design |

| Dubbeldeman et al. [100] | Intervention characteristics and mechanisms and their relationship with the influence of social prescribing: A systematic review | Systematic review | UK (majority) | Adults | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Community-based | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Impact on participants |

| Evers et al. [101] | Theories used to develop or evaluate social prescribing in studies: a scoping review | Scoping review | UK (majority) | ∗ | Not specified | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Community-based | ∗ | Developing theory |

| Feather et al. [102] | Locating the evidence for children and young people social prescribing: Where to start? A scoping review protocol | Protocol for scoping review | ∗ | Children and young people | Mental health (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | Community-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific patient group |

| Iverson et al. [103] | A rapid systematic review of the effect of health or peer volunteers for diabetes self-management: Synthesizing evidence to guide social prescribing | Rapid review | HICs (majority) | Adults | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | ∗ | Psychosocial | General health or wellbeing | Impact on participants |

| Jensen et al. [104] | The impact of arts on prescription on individual health and wellbeing: a systematic review with meta-analysis | Systematic review | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | Arts and culture | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Lavelle Sachs et al. [105] | Connecting through nature: A systematic review of the effectiveness of nature-based social prescribing practices to combat loneliness | Systematic review | ∗ | Various ages | Loneliness | ∗ | ∗ | Green or nature-based | Loneliness/connectedness | Specific SP intervention |

| Marshall et al. [106] | Social prescribing for people living with dementia (PLWD) and their carers: What works, for whom, under what circumstances and why—protocol for a complex intervention systematic review | Protocol for systematic review | UK (all) | Various ages | Dementia | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | ∗ | ∗ | Specific patient group |

| Menhas et al. [107] | Does nature-based social prescription improve mental health outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis | Systematic review | Other | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Green or nature-based | Mental health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| Mosteiro Miguéns et al. [108] | Community activities in primary care: A literature review | Literature review | HICs (majority) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Community-based | General health or wellbeing | Specific SP intervention |

| O’Grady et al. [109] | The role of intermediaries in connecting community-dwelling adults to local physical activity and Exercise: A scoping review | Scoping review | HICs (majority) | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Physical activity | ∗ | Specific SP intervention |

| O’Sullivan et al. [110] | The effectiveness of social prescribing in the management of long-term conditions in community-based adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Systematic review | USA (majority) | Adults | Physical or mental health | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Community-based | Physical activity | Impact on participants |

| Oliveira et al. [111] | Impact of social prescribing intervention on people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a primary healthcare context: a Systematic literature review of effectiveness | Systematic review | UK (majority) | Adults | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Specific patient group |

| Rasmussen et al. [112] | Social prescribing initiatives connecting general practice patients with community-based physical activity: A scoping review with expert interviews | Scoping review | HICs (all) | Adults | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Physical activity | ∗ | Specific SP intervention |

| Sadio et al. [113] | Social prescription for the elderly: a community-based scoping review | Scoping review | UK (majority) | Older adults | ∗ | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | Community-based | ∗ | Specific patient group |

| Staras et al. [114] | An evaluation of the role of social identity processes for enhancing health outcomes within UK-based social prescribing initiatives designed to increase social connection and reduce loneliness: A systematic review | Systematic review | UK (all) | ∗ | Loneliness | ∗ | Does not specify link worker or equivalent | ∗ | ∗ | Developing theory |

| Tierney et al. [115] | Community initiatives for well-being in the United Kingdom and their role in developing social capital and addressing loneliness: A scoping review | Scoping review | UK (all) | Adults | Loneliness | ∗ | ∗ | Community-based | Loneliness/connectedness | Specific SP intervention |

| Turk et al. [116] | A meta-ethnography of the factors that shape link workers’ experiences of social prescribing | Meta-ethnography | UK (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Developing theory |

| Yadav et al. [117] | A rapid review of opportunities and challenges in the implementation of social prescription interventions for addressing the unmet needs of individuals living with long-term chronic conditions | Rapid review | UK (majority) | ∗ | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Specific patient group |

| 2025 | ||||||||||

| Bhaskar et al. [118] | Exploring ambiguity in social prescribing: Creating a typology of models based on a scoping review of core components and conceptual elements in existing programs | Scoping review | HICs (all) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | Community-based | ∗ | Developing theory |

| Handayani et al. [119] | Experiences of social prescribing in the United Kingdom: a qualitative systematic review | Systematic review | UK (all) | Adults | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Impact on participants |

| Muhl et al. [120] | Social prescribing for children and youth: A scoping review | Scoping review | UK or USA (all) | Children and young people | ∗ | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | ∗ | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Specific patient group |

| Mulholland et al. [121] | The social prescribing link worker—clarifying the role to harness potential: A scoping review | Scoping review | UK (majority) | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Link worker or equivalent (only) | ∗ | ∗ | Service design |

| Pilkington et al. [122] | Social prescribing for adults with chronic pain in the U.K.: a rapid review | Rapid review | UK (all) | Adults | Physical health—chronic conditions (primarily) | ∗ | May involve link worker or equivalent | ∗ | Health and wellbeing and health service use | Specific patient group |

| Tierney et al. [123] | Digging for literature on tailoring cultural offers with and for older people from Ethnic minority groups: A scoping review | Scoping review | UK (all) | Older adults | ∗ | Racialised individuals/groups | ∗ | Arts and culture | ∗ | Specific patient group |

In total, 42 quantitative or qualitative systematic reviews, 17 scoping reviews and 8 realist or rapid realist reviews on social prescribing topics were found. There were 25 other reviews, with a range of designs, including critical, integrative, mapping, narrative, systematised and umbrella reviews, and five protocols for as-yet unpublished reviews.

A substantial majority (70 reviews, 72%) reported that all or most of their included studies were from high-income countries. 42 reviews (43%) drew all or most of their studies from the United Kingdom alone.

Thirty-three reviews focussed on adults, nine on older adults, five on children and young people, and six on a range of ages. Two reviews focussed on students. The remaining 42 reviews did not specify an age group of interest.

Over half the reviews (53%, 55%) did not specify a particular health reason why participants might be referred to social prescribing. Of those that did, 15 reviews focussed on participants referred primarily for mental health reasons, 10 for chronic physical health conditions, eight for loneliness and seven for general physical or mental health. Autism [57], neurodivergence or neurodisability [77], dementia [106] and suicide risk [98] were each the focus of one review.

Eight reviews identified their participant group of interest based on a social determinant of health. These included acute financial uncertainty [43], migration status [47], housing issues [49], food insecurity [60], belonging to a racialised population group [89, 123], unmet social needs [99] and conditions imposed by the pandemic [67]. A further three studies combined social determinants and health or wellbeing criteria: One looked at chronic physical health conditions in combination with unmet social needs [65] and two at mental health in combination with socioeconomic disadvantage [71, 92].

Most reviews (70, 72%) provided some information about the model of social prescribing they were investigating. Of these, 31 focussed only on social prescribing models which included a link worker or equivalent role, 16 included link workers among other kinds of referrals, and 23 did not specify whether a link worker was involved in referrals from healthcare to community settings.

Around half the reviews (50, 52%) described the interventions that people might be referred to. Eleven of these focussed on green or nature-based interventions, five on arts and culture, three on physical activity, three on psychosocial support, two on volunteering, one on food, and one on housing advice. The other 24 reviews which described interventions referred to a range of ‘community-based activities’, some or all of which may also fit into the categories above.

The main health outcomes of interest were to do with general health and wellbeing, including physical and mental health (22), mental health and wellbeing alone (15) or loneliness and social connectedness (10). A further 10 studies focussed on general health outcomes together with measures of health service usage and one on health service usage alone. There was one review each looking at outcomes related to physical activity, suicide prevention, person- and system-level outcomes and food access.

In addition to their key characteristics, we sought to describe the broad purpose of each review. We use short codes to summarise these in Table 2, and these are provided in brackets here beside the fuller explanation. We found 45 reviews which aimed to assess the impact of social prescribing on health or other outcomes for people who use it: 21 focussed on participants in general (‘impact on participants’) and 24 on specific groups of people, defined by a health condition, age group or social determinant (‘specific patient group’).

We found 22 reviews which aimed to evaluate the impact of a specific social prescribing intervention, such as nature-based or cultural activities (‘specific SP interventions’). Sixteen addressed the design of social prescribing services, for example by exploring barriers and facilitators to effective social prescribing, identifying best practice, clarifying the role of the link worker or understanding the mechanisms or components which have most impact on social prescribing’s effectiveness (‘service design’).

Finally, 14 reviews were interested in articulating or evolving the conceptual boundaries of social prescribing itself. Five focussed on how social prescribing was or should be defined (‘defining social prescribing’) [29, 53, 65, 83, 86] and four on developing or articulating theories that inform social prescribing practice or evaluation (‘developing theory’) [101, 114, 116, 118]. Another five studies sought to develop tools, principles or frameworks for evaluating social prescribing programmes or interventions (‘evaluation’) [56, 58, 79, 94, 95].

3.3. Themes Related to Place

No literature reviews were identified that fully engaged with concepts of place as part of their research aims or objectives. However, 31 reviews engaged partially with the concept, typically in the analysis of their findings [31, 32, 35, 39, 44, 46, 58–60, 66, 67, 70, 71, 73, 76, 78, 84, 87–89, 97, 101, 105, 107, 113, 115–119, 123].

Within those reviews, we identified five overlapping but distinct ways of thinking about place: place as healing, experience of societal inequalities and its effect on place, how deprivation shapes place, place as the context for social prescribing and alternative conceptions of place.

3.3.1. Place as Healing

Seven reviews conceived of (some) places as having healing or health-creating properties. Six were reviews of nature-based interventions [32, 66, 70, 84, 105, 107]. One looked at the role of accessible physical infrastructure in creating places where older adults feel familiar and safe [78].

This approach helps to identify features of place which may have health benefits, such as green or blue spaces, parks or gardens, and, as such, allows the health-creating properties of different locations to be compared.

3.3.2. Experience of Societal Inequalities and Its Effect on Place

Six reviews explored how barriers facing individuals, due to particular socioeconomic or structural factors, affect their experiences of a given place [32, 35, 60, 78, 89, 123]. Barriers can be caused by a lack of accessibility in neighbourhood design or transport planning [35, 78, 123]. Processes of marginalisation or racialisation can also affect people’s access to, or relationship with, places: particularly their sense of safety and welcome [32, 89].

This approach permits an understanding of how the same places, neighbourhoods, green spaces and community activities might be experienced differently because of societal inequalities. These inequalities create disproportionate barriers to access and enjoyment for some individuals and groups.

3.3.3. How Deprivation Shapes Place

Six reviews examined social prescribing in the context of socioeconomic deprivation [58, 71, 101, 113, 116, 119].

Some of these reviews analysed deprivation as an individual characteristic, which may shape people’s behaviour and choices [119], or inform their level of risk [58]. This approach links to the previous theme and could be expanded to examine how individuals’ experiences of socioeconomic deprivation affect their interaction with places.

A more direct link between social prescribing, deprivation and place is established by two papers, which considered socioeconomic deprivation as a property of the locations where social prescribing takes place [71, 116]. Turk et al. [116] identified the tension created by ‘local variation and structural poverty’ in access to community resources (p. 18), as an important challenge for social prescribing. Bernard et al. [71] found that the ‘socioeconomic environment’ affected the impact of social prescribing interventions at the level of place or community, as well as at individual level. Austerity measures meant that community organisations lacked the resources to run interventions that could contribute to social prescribing or depended on ‘short-term and unpredictable’ funding to do so. Bernard et al. [71] described a vicious circle, as this short-termism and insecurity had a particularly detrimental impact on participants’ mental health, which was the reason why they had been referred for social prescribing initially.

3.3.4. Place as the Context for Social Prescribing

Sixteen reviews discussed place as part of the context in which social prescribing occurs [31, 39, 44, 46, 59, 67, 76, 87, 88, 97, 113, 115–119].

In different ways, these reviews all acknowledged that the community infrastructure of a specific place is relevant to the way social prescribing works and that community infrastructure varies between places in ways that could affect social prescribing. For example, Pescheny et al. [31], one of the earliest publications in this review, described the importance of a ‘wide range of good quality third sector-based services and activities, easily accessible with public transport’ for effective social prescribing (p. 9).

For most of the reviews in this category, this is a small part of an analysis which is predominantly focussed on other aspects of social prescribing. Importantly, however, several reviews contribute frameworks or models which may help future researchers to think about the role of place in the context of social prescribing.

One such framework was developed by Calderón-Larrañaga et al. [39], incorporating three dimensions of social prescribing: the link worker, the general practice context and the voluntary–community sector. This final dimension could allow social prescribing to be analysed in a broader context, potentially including the community infrastructure of the place in which it is done. However, the ‘voluntary–community sector’ label does not necessarily invite a focus on wider characteristics of place, such as green space or neighbourhood design. For example, Ebrahimoghli et al. [76] adopted this framework for their analysis, but focussed strictly on the characteristics of voluntary and community organisations, rather than wider community infrastructure.

Another organising framework, used by several reviews, is NHS England’s [124] Common Outcomes Framework, which suggests that social prescribing should be assessed in terms of its impact on (a) the person, (b) community groups and (c) the health and care system. Two reviews adopt a wider lens, interpreting the second level as ‘the community’ in general [44, 46]. Their analysis of the relationship between social prescribing and communities is not extensive, but the building blocks for understanding the role of place are laid.

This framing also enables us to see the relationship between social prescribing and place as a two-way street, with communities potentially being changed in measurable ways by the operation of social prescribing within them [46]. The idea of a reciprocal relationship between people and places, facilitated by social prescribing, has emerged further in more recent reviews, recognising how community engagement may foster a sense of belonging [59] or enhance community unity [119].

A third model is provided by Bhaskar et al. [118], who categorised social prescribing programmes into four conceptual models, reflecting the differing policy aims and components of different schemes. Their ‘healthy community’ model sees social prescribing as contributing to a resilient and health-creating community. This model might provide another way of thinking about the role of community infrastructure in social prescribing, although the authors found few schemes which would fit into this model at present, and did not discuss it in depth [118].

Finally, a couple of reviews focussed on processes which could enable the characteristics of specific places to be taken into account in social prescribing practice. These reviews described tailoring [125] or matching [88] to ensure a good fit between individuals and interventions within social prescribing programmes—a process which is affected by the availability and suitability of what can be offered to social prescribing participants in a particular place.

3.3.5. Alternative Conceptions of Place

Three reviews [73, 87, 113] explored whether online or phone-based community resources could form part of social prescribing, particularly for people who do not, or cannot, engage with in-person support. This suggests that there may be a need to think beyond place and community as physical locations, and also reflects on the role of online (or other non-local) communities and shared spaces as part of social prescribing.

3.4. Social Prescribing and Place in Primary Research

Exploratory scoping searches in PubMed for primary studies of place and social prescribing returned 83 results, without de-duplication. After screening titles and abstracts, eight unique papers were included (see Supporting Table S3).

These papers can be divided into three groups. The first set of three [126–128] reaffirmed findings from the literature reviews, such as the importance of physical accessibility and good transport [126]; feelings of belonging and ‘sense of place’ [127]; and the potential health benefit of specific features, in this case rivers and canals, in the local area [128].

The second set of three studies [15, 129, 130] took place in specific localities, which were analysed or evaluated in depth. This enabled specific characteristics of the local area—such as the strength of the voluntary sector [129], the spirit of community cohesion [129, 130] or the impact of reduced funding for voluntary services [15]—to be brought to light in detail.

Finally, two studies advanced theoretical understandings of the role of place in social prescribing [131, 132]. Pedell et al. [132] drew on the WHO framework of age-friendly cities to identify specific neighbourhood characteristics that promote the health of older adults in the context of social prescribing, including accessible outdoor spaces and public infrastructure, ‘smart’ (digitally connected) environments and community services that promote social participation. Morris et al. [131] proposed a model and methodology for developing ‘community-enhanced social prescribing’, with the aim of improving wellbeing outcomes for both individuals and communities, by increasing connectedness, collective action and self-organisation within communities.

4. Discussion

4.1. Past and Future Research Directions

Social prescribing is emerging as a distinct area of focus in research, policy and practice [1]. There has been a steady increase in academic publications on social prescribing in recent years, which mirrors a growing focus on social prescribing among practitioners and policymakers, particularly in the United Kingdom [13, 133–135].

This review presents a timeline of trends and directions in social prescribing research to date, as reflected in literature reviews. The timeline demonstrates that most research has focussed on understanding the impact of social prescribing on individuals, or ways in which social prescribing service design can be improved. General health and wellbeing, or mental health and wellbeing specifically, have so far been the main outcomes of interest.

No literature reviews to date have fully engaged with the role of place in social prescribing, and we found little evidence of an emerging focus in primary studies. However, the role of place was explored, typically in quite a limited sense, in about a third of the literature reviews. Consistent themes included the healing or health-promoting aspects of place, the interaction between societal inequalities and the way that people experience places, the impact of deprivation in shaping places or communities, alternative (e.g., digital) conceptions of place and the role of place as part of the wider context in which social prescribing occurs.

This last concept is likely to be the most productive, in terms of understanding the relationship between place and social prescribing. In this category, we identified several frameworks which could be used to analyse the relationship between place and social prescribing [39, 118, 124]. In particular, the framework drawn from NHS England [124] has been used by Reinhardt et al. [44] and Vidovic et al. [46] to capture the relationship between social prescribing and community in a general sense, while the framework from Calderón-Larrañaga et al. [39] could lend itself to a similarly broad interpretation. A pre-existing framework, on age-friendly communities, is strongly oriented around place and could also be applied in analyses of social prescribing [132].

Conceptual frameworks need to be populated with actual dimensions of community infrastructure, in order to support analysis. Accordingly, there is a need to identify what features of community infrastructure are most relevant for social prescribing. There is scope to expand research in this area, beyond a focus on nature-based solutions, to include tangible and intangible qualities of places: from accessible infrastructure, to community-led initiatives and sense of social cohesion.

Conversely, research which looks at social prescribing in a digital context may challenge or expand our concepts of place or community. Nonphysical alternatives may either complement place-based approaches or offer an alternative for those who feel marginalised and ‘out of place’ in their local area [19] or who are otherwise unable to engage with physical community-based support; although the risk that these could further entrench isolation should also be acknowledged [113].

A small number of papers indicated a reciprocal relationship between social prescribing and place. As well as providing the community infrastructure needed for social prescribing, we might expect social prescribing initiatives to contribute to community wellbeing [44, 46, 59, 119, 131]. This is another area in which further research could help to articulate the community-level benefits of social prescribing, and how these might be achieved.

Overall, there are some promising directions for future research addressing place and social prescribing. These may include expanding frameworks to incorporate a broad place-based dimension, investigating specific features of places which may be particularly relevant for social prescribing and exploring how social prescribing can contribute to community-level wellbeing outcomes. In-depth comparative case studies may be especially useful for identifying the relationship between community infrastructure and social prescribing in specific places: exploring whether these relationships are highly place-specific or whether there are identifiable features of community infrastructure which consistently interact well with social prescribing.

4.2. Addressing the Scottish Context

The relationship between place and health, in general, is an active area for policy development in Scotland. Scotland has a broad range of legislation and policies involving place-based approaches to health and wellbeing. These include legislation focussed on local decision-making, such as the Community Empowerment Act (Scotland) 2015, and economic development through Community Wealth Building [136]. A set of Place and Wellbeing Outcomes form part of Scotland’s National Planning Framework, designed to integrate this across policy and practice [137].

However, financial decisions in Scotland and the United Kingdom continue to challenge place-based approaches: from the Scottish Government’s in-year budget reductions [138] and to the continuation of austere financial policies by successive UK Governments [139]. In Scotland, the recent ‘Better Places’ statement highlighted the variable quality of places and communities, linked to poverty and deprivation, and its impact on widening health inequalities [140]. Recent studies have found that many measures of health inequality are worsening in Scotland, and overall life expectancy is deteriorating, with people in more deprived areas being at much higher risk of premature death [5, 141].

There is unwarranted variation in community infrastructure from place to place, in Scotland and across the United Kingdom: The communities most affected by austerity and deprivation are also most likely to experience reduced quality and availability of voluntary, community and public sector assets [5, 11]. There are demonstrable inequalities in health linked to place, with people in the most deprived areas experiencing the worst outcomes [7]. Social prescribing relies on access to a good range of community resources [15]. However, social prescribing services in more deprived places are likely to confront a ‘double inverse care law’, affecting the availability of community resources as well as primary health care in these areas.

In Scotland, this concern is especially acute because the Scottish Government has framed social prescribing as a response to health inequalities and prioritised funding for social prescribing services in more deprived parts of the country [142]. Whether or not social prescribing is able to tackle the root causes of health inequality [12, 143], it certainly aims to mitigate their harms [3]. However, it may face an uphill struggle in doing so, if the community infrastructure it needs is absent or unstable due to the effects of deprivation [5, 11]. Indeed, this may even lead to harm instead of health [71]. With this context in mind, understanding the interactions between place and social prescribing is essential for coherent policy approaches which take into account the whole ecosystem in which social prescribing operates.

4.3. Strengths, Limitations and Reflections on This Review

As demonstrated in this review, very little research focusses directly on the role of place in social prescribing, meaning that this area does not lend itself well to systematic or scoping reviews at present. A state-of-the-art methodology enables emerging ideas about place and social prescribing to be put in the context of a broad overview of social prescribing literature, giving an overview of research directions to date and suggesting potential ways forward.

However, there is no detailed academic consensus about state-of-the-art review methodology. This may lead to poorly considered or nontransparent methodological choices. To mitigate this, the authors adopted a published methodology [17] and included detailed methods to aid transparency, using the PRISMA 2020 statement where possible [18].

Social prescribing is in the process of evolving a clear identity. As shown by recent attempts to develop definitions [1], a broad range of practices sit under the umbrella of social prescribing, described with diverse language and labels. The searches for this review used ‘social prescribing’ and closely-related terms to locate papers that directly address social prescribing as an emerging field of professional practice, policy-making or academic research. However, similar practices described in different terms may have been missed.

Practical methodological choices may also have limited the quality of this review. Limiting the search to titles and abstracts may have missed papers which do not have a primary focus on this topic, but which provide useful insights in passing. Screening by one reviewer will inevitably have reduced rigour. The choice of databases aimed to balance a manageable search with coverage of a wide range of disciplines; however, as this topic is known to be under-researched, a broader search may have helped to unearth fresh perspectives. This review focussed on academic literature rather than grey literature, both for reasons of scale, and because academic literature reviews have a particular use as signposts of current research directions. Making sense of the rich information contained within nonacademic reports would be an undertaking in its own right and would undoubtedly add further valuable insight.

Our exploratory searches of primary research are a qualified strength of this review. As scoping searches, they are very limited and are not held out to be a complete picture of the state of primary research. However, they add value by acting as a sense check for our analysis of literature reviews and appear to confirm that there is not a significant mismatch between primary research and literature reviews on this topic. Finding relevant primary research on place and social prescribing may be a particular challenge for future reviewers, as studies contributing to this field might focus on one specific place, rather than ideas of place in general. As such, developing frameworks which allow researchers to use a common language around place and community infrastructure in social prescribing is all the more important.

Through its overview of social prescribing literature reviews, this review offers insights into the scope and priorities of research in a rapidly expanding area. The timeline created for this review (Table 2) may be useful in its own right to a broad range of social prescribing researchers. Given the rapid growth in research on social prescribing, this overview of developments and milestones is particularly timely and may soon be far less feasible to complete from scratch.

The authors are most familiar with Scottish and UK approaches to social prescribing, and many of the included papers are from a UK context. This will inevitably have skewed our findings and interpretations towards certain models and political contexts. However, place-based inequalities are a feature of societies around the world. In that sense, it is possible to generalise this review’s findings: that such inequalities need to be accounted for in the design of health interventions that rely on the features of their surrounding community, such as social prescribing.

5. Conclusions

This state-of-the-art literature review aimed to examine the extent to which social prescribing research has engaged with places and communities. It provides an overview of trends in academic thinking about social prescribing, through a timeline of social prescribing literature reviews; analysing the extent to which ‘place’ has emerged as a concept; and exploring how primary research studies have engaged with social prescribing and place.

Overall, findings related to place have emerged in a number of social prescribing studies and reviews. These can be organised around five themes: place as healing, experience of societal inequalities and its effect on place, how deprivation shapes place, place as the context for social prescribing and alternative conceptions of place. However, place has not so far been central to research on social prescribing. To the authors’ knowledge, this review is the first to bring together an overview of research directions and trends related to the role of place in social prescribing and to articulate the importance of better understanding this relationship.

Building on existing research, there is scope to develop a greater understanding of the role of place in social prescribing, by expanding existing conceptual frameworks for social prescribing and investigating what features of community infrastructure may be particularly relevant to social prescribing. This may help to inform policy development which addresses the whole ecosystem around social prescribing, including the characteristics of the places where it happens and the effect that deprivation may have on access to community resources.

Disclosure

The funder had no role in the conduct of the study, interpretation or the decision to submit for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Legal and General.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The co-authors are employees of the University of Edinburgh (E.D., J.G. and S.W.M.) and Newcastle University (A.O.) and supervise the lead author (E.M.) in the course of their employment.

Funding

This research was funded by the Legal and General Group (research grant to establish the independent Advanced Care Research Centre at University of Edinburgh).

Acknowledgements

Paul Kelly is part of the Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) network of the Advanced Care Research Centre and acts as PPI mentor to EM for her PhD research. Kevin Chalmers has also contributed PPI insights. We are grateful for Paul and Kevin’s contributions to the development of the ideas that shaped this work and to Paul for his review and feedback on a draft of this paper.

Supporting Information

Table S1: Search strings by database for literature reviews related to social prescribing.

Table S2: Initial descriptions of study characteristics and final codes used in timeline.

Table S3: PubMed searches for primary research related to place and social prescribing.

Table S4: PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supporting information of this article.