Stay or Return: A Qualitative Exploration of the Experiences of Malawian Migrants Who Returned From South Africa During Covid-19

Abstract

Covid-19 created unprecedented disruptions on human migration. Business closures and travel bans disproportionately impacted economic migrants who were neither able to support their families nor travel to their home countries. The primary aim of the study was to explore the experiences of Malawian migrants who returned from South Africa during Covid-19. A secondary objective was to explore solutions to the migration-related challenges that migrants experienced. A qualitative approach involving 15 in-depth interviews with Malawian migrants living in South Africa who returned home during Covid-19 was used. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed thematically. Three main themes emerged from the data and revolved around the migration stages, namely, the pre-return/departure stage, the travel/transit phase, and the return and reintegration. Within these migration phases, participants reported failure to integrate with host community, fear of dying in a foreign country, financial hardship, corruption, risk of contracting diseases due to limited hygiene, and economic hardships in the home country as some of the main challenges they dealt with. Reintegration with family members was generally very positive as most migrants indicated that their family members were happy to see them alive. To effectively mitigate these challenges at various phases of the migration cycle, there is a need for swift and better coordination and policy change at the governmental level to take actions that support and protect migrants, as well as community and individual level actions such as saving money for emergencies.

1. Introduction

For generations, people have migrated for various reasons, including the search for food, work, and improved health and well-being. In recent years, the Covid-19 pandemic, with its associated travel restrictions and border closures, along with reduced economic opportunities, significantly impacted human migration. The challenges the world experienced around human mobility during Covid-19 underscores an urgent need to focus on the health and well-being of migrants, particularly international migrants.

According to United Nations estimates, there are approximately 281 million international migrants worldwide, representing 3.6% of the global population [1]. The number of people on the move, both within and between countries, continues to increase due to a variety of push and pull factors. These factors include economic opportunities, as seen in regions such as North and Southern Africa, South-East Asia, and the Middle East [2–4], and political instability in countries like Ukraine, Gaza, Zimbabwe, Malawi, the Syrian Arab Republic, Yemen, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Myanmar [5]. Additionally, violence, climate change, and other disaster-related challenges, such as those in Pakistan, the Philippines, China, India, Bangladesh, Brazil, and Colombia, further drive migration [6].

As of mid-2020, approximately 6.4 million of the 363.2 million people living in Southern Africa were international migrants [7, 8]. These migrants primarily moved in pursuit of economic opportunities in countries with stronger economies, such as South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, and Angola [7]. During the same period, South Africa alone had about 2.9 million international migrants, drawn by its industrialized economy that offers better education and economic opportunities [7].

In their study, Jolivet et al. [9] explored the different mechanisms through which Covid-19 pandemic affected individual mobility decision-making practices. Using the aspiration–ability framework, they reported that the Covid-19 pandemic affected migration decisions through the direct impacts of barriers that restricted mobility such as stringent population movement controls (e.g., travel bans and border closure), the impact of economic changes (i.e. reduced ability for migrants to maintain livelihoods, increased costs of mobility), and through the impacts on aspirations to move. The aspiration–ability framework perceives migration decisions “as a function of aspirations and capabilities to migrate within given sets of perceived geographical opportunity structures” [10]. Thus, while migrants leave their countries in search of better livelihoods or safety, they often encounter numerous challenges both during their migration journeys and in their destination countries [11, 12]. These challenges range from exclusion or limited access to essential social services, such as healthcare, housing, and water and sanitation, to issues like gender-based violence, poor wages, and language barriers, among others [13, 14]. All these issues negatively impact the health and well-being of migrants. For instance, Covid-19 disproportionately affected economic migrants as businesses shut down, forcing them into temporary or permanent unemployment [15]. The lockdowns and border closures added stress and anxiety about travel prospects [16].

For many migrants, especially those separated from their families, being unable to return home due to Covid-19 restrictions and lacking a reliable income because of social distancing and border mandates were deeply traumatic experiences [17–20]. Many migrants found themselves at a crossroad, deciding whether to remain in countries with diminished employment opportunities or return to their home countries, which were facing similar pandemic challenges and often worse economic stability. At this juncture, migrants carried a myriad of concerns, such as uncertainty about the length of the lockdown, fear of being abandoned by their employers, anxiety about health issues or death in a foreign land or during the journey home, and worries about the safety and comfort of their families in their native places [21].

Designing interventions that can help to reduce migrant vulnerabilities during crises calls for more systematic and comparative research to explore the processes through which the Covid-19 pandemic affected migration decisions [9, 22]. To do this, the concept of migrant transnationalism serves as a theoretical framework to understand the multifaceted and interactive effects of individual, policy, and environmental factors that contribute to migrant integration. Migrant transnationalism has been defined as the process by which immigrants build and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their country of origin and their country of destination [23, 24] and is also related to the integration of migrants in the country of settlement [25, 26]. Thus, these social relations can provide bonding and bridging social capital that help migrants settle and navigate new socioeconomic landscape in their country of settlement. Phillimore [27] argues that the successful integration of international migrants into host countries, while complex, happens when migrants develop (i) a sense of belonging to the host community, (ii) social relationships and social networks, and (ii) the means and confidence to exercise rights to resources such as education, work, and housing.

As our understanding of transnationalism in international migration evolves, the Covid-19 pandemic provided an extremely enriching opportunity to learn about transnationalism during a crisis. Taking a holistic before–during–after perspective, this study explores the experiences of Malawian migrants in South Africa who chose to return to their country during Covid-19. Our approach to migrant transnationalism extends beyond the home–host country interrogation to include migrants’ experiences in “third-places” such as in-transit passage through Zimbabwe or Mozambique. This paper also draws on the migration cycle framework, looking at their experiences and decisions made at the different phases of the migration process.

1.1. The Migration Cycle Phases of Migration

Modern migration is a complex, multistage process that individuals can enter and exit multiple times and, in several ways, occurring either within or across national borders. The International Organization for Migration [28] and Wickramage et al. [29] provide valuable illustrations of the various phases of migration and factors influencing the health of migrants in their migration journey. To better understand the experiences of Malawian migrants returning from South Africa, we used three distinct phases aligning with these models: pre-departure, travel/transit, and return and reintegration, while also discussing potential solutions to reduce migration vulnerability.

The pre-departure phase is the period before individuals leave their place of origin, involving an evaluation of the host country’s benefits versus home options [28]. In labor or economic migration, factors like economic opportunities, cultural values, language, and geographic proximity influence migration decisions and duration [30, 31]. The travel phase involves transit between the place of origin and the destination, whether moving to another country, returning home, or traveling within the same country [28]. For Malawian migrants returning from South Africa, this included multiple “transit” locations like ports of entry or border control stations in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, or Zambia. This phase was critical during the Covid-19 pandemic, posing a risk of virus spread due to South Africa’s higher infection rates and increasing the risk of negative encounters with law enforcement due to travel restrictions.

The final phase, and of particular relevance to our study, is the return and reintegration phase, which refers to the process of re-incorporating returning migrants into their home society [28]. Reintegration is an important phase of migration because it influences whether individuals will stay or enter into circular migration whereby they will return to the country they had migrated to or migrate to another country.

Experiences in each of these phases can independently or collectively shape the migratory behaviors of people. Our study seeks to explore migrant experiences and solutions to some of the challenges they experience, not only in their host countries but also experiences with re-integrating into home communities. Specifically, we ask the questions: What are the experiences of Malawian migrants who returned from South Africa during Covid-19? How did the Covid-19 crisis influenced stay in or leaving the host country, travel to Malawi, re-integration in Malawi, and decisions to stay or return to South Africa or another country? What are the potential solutions/interventions to the migration-related challenges that migrants experience?.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

An exploratory qualitative design with a descriptive approach was used to investigate the experiences by Malawian migrants who returned home from South Africa during the Covid-19 pandemic. Qualitative design helped us delve deep into participants’ lived experiences amid the global public health crisis that led them to embark on the arduous journey back to their homeland. This study helped us uncover Malawian migrants’ concerns, fears, and voices and develop contextually relevant recommendations to reduce socioeconomic and health vulnerabilities [32]. The design’s exploratory and descriptive nature helped to inductively develop themes and new insights that were supported by detailed participant accounts, capturing all relevant themes [33, 34].

2.2. Setting and Study Participants

Malawian migrants who returned from South Africa during the Covid-19 pandemic were recruited using a combination of purposive and snowball sampling. Migrants who were (1) Malawian nationals, (2) 18 years old and above, (3) who resided in South Africa before and during the Covid-19 pandemic, and (4) who returned to Malawi during the pandemic were recruited. A total of 15 participants who met the inclusion criteria were selected and included in the study (Table 1).

| Participant | Gender | Marital status | Number of years in South Africa (years) | Date of return to Malawi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | Female | Married | 2 | 11/2020 |

| Participant 2 | Male | Single | 3 | 03/2022 |

| Participant 3 | Male | Separated | 6 | 2021∗ |

| Participant 4 | Female | Single | 3 | 12/2021 |

| Participant 5 | Male | Single | 4 | 10/2021 |

| Participant 6 | Male | Married | 10 | 2021∗ |

| Participant 7 | Female | Married | 14 | 06/2021 |

| Participant 8 | Male | Separated | 6 | 2021∗ |

| Participant 9 | Female | Married | 2 | 08/2022 |

| Participant 10 | Male | Married | 12 | 03/2022 |

| Participant 11 | Female | Married | 5 | 03/2022 |

| Participant 12 | Female | Single | 3 | 06/2022 |

| Participant 13 | Male | Married | 10 | 08/2022 |

| Participant 14 | Male | Single | 2 | 06/2022 |

| Participant 15 | Female | Single | 7 | 07/2020 |

- ∗Three participants did not remember the exact month they returned to Malawi.

2.3. Data Collection

One-on-one in-depth interviews were conducted with participants using a semi-structured interview guide between September and October 2022. The interview guide was developed by the researchers based on the objectives of the study. The interviews therefore focused on getting a deeper understanding of participants’ experiences while in South Africa when the pandemic hit, what made them decide to return to Malawi, what their transit experiences, i.e., what challenges they faced, how they were received on arrival in Malawi and their integration with their families, and finally what were their recommendation for the future if a similar crisis occurred. The interviews were conducted face to face as well as remotely because participants were based in different places in Malawi, which rendered it costly to travel to the various places to do face-to-face interviews. The remote interviews were conducted telephonically using local telephone lines in the country, which are usually stable unlike WhatsApp calls that could easily experience network connectivity challenges. Two researchers, the PI, and one research assistant conducted the 30–45-min interviews in English and Chichewa (a Malawian language) based on participants’ preferences. Recruitment and interviews were discontinued after data saturation was reached [35]. Interviews were audio-recorded and stored in a secure and password-protected computer. An informed consent document was provided and explained to participants. Participants were assured that their personal information would remain confidential and that the data would be de-identified and anonymized.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis followed an inductive thematic analysis. The process started with transcribing the interviews and translating those in Chichewa into English. First, five transcripts were selected and were read by the whole research team to identify common themes and codes. A test coding was run manually on the selected transcripts. Each team member took notes while reading the transcripts and developed a list of potential themes and codes. Then, the team convened to discuss on the list of themes and codes from each member and recategorize as well as integrate themes and codes. Then, a draft comprehensive codebook was developed. Before finalizing the codebook, the team members read through the rest of the transcripts to identify and integrate additional themes and codes to the codebook. The iteratively developed codebook and transcripts were imported and coded using Nvivo12 qualitative software. The second and third authors double-coded each transcript. Then, an inter-coder reliability test was performed that demonstrated differences and similarities in coding. The two coders held a series of meetings to go through each transcript to check and reconcile coding differences. After the coding reconciliation was completed, an inter-coder reliability test was run again and an overall Cohen’s Kappa of 0.85, which is considered substantial agreement [36]. The first and fourth authors audited and reviewed code reports for accuracy. Interview notes were used as additional resources to ensure the inclusion of important themes and guided the analysis.

2.5. Researchers

All researchers were of African descent living outside their countries of origin. The PI, ML led the project. ML is a PhD-trained Malawian public health scholar with extensive experience on migration issues within an African context. The other three researchers (WM, ID, and GT) are also of African descent, WM (Zimbabwe), ID (Seirra Leone), and GT (Ethiopia). WM, an associate professor of public health (PhD), worked with ID and GT, who were PhD candidates in Health Rehabilitation and Social Work, respectively, to code and analyze data. All authors participated in writing and reviewing the manuscript under the leadership of the first author. The research team members combined their passion for migrant health research, public health expertise, and in-depth knowledge of African contexts to conduct the study. The research team was aware of the influence of their positionality as migrants, researchers, and existing knowledge about Malawian migrants’ lives in South Africa and applied reflexivity to reduce potential biases from influencing the overall research process and findings [37].

2.6. Ethics

The researchers received two ethics approvals for the study. The first approval was provided by the University of the Western Cape Biomedical Research Committee (BMREC) with reference number BM21/5/10. The second ethics approval was provided by the Malawi College of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (COMREC) with reference number P.11/21/3467. Permission to conduct interviews in Malawi was also granted by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship and the Department of Disaster Management.

3. Findings

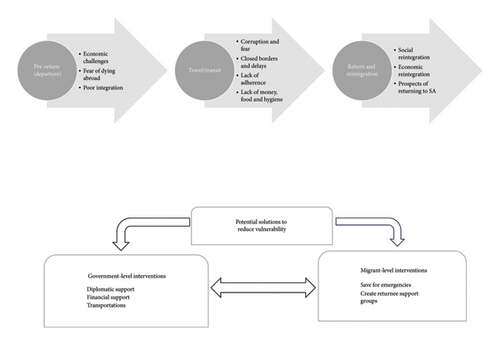

The themes from the analysis were grouped under three broad migration stages within the migration cycle/model: pre-return/departure, travel, and return and reintegration. An emergent theme of solutions was included as the fourth category. Each domain has several sub-themes that reflect the participant’s experiences at each stage (Figure 1).

3.1. Domain 1: Pre-Return/Departure

Under normal circumstances, before international migration takes place, be it outward or return migration, those intending to migrate/return prepare for their departure, travel, and arrival. In some cases, this can be done over an extended period. For example, planned migration may take years as migrants prepare needed documentation, identify potential host communities, and save money for travel and settling in expenses. In other cases, particularly in the context of pandemics, disasters, or wars, the pre-departure phase is compressed, and travel is extended by events beyond the control of the migrants. For most Malawian migrants who decided to return to their home country, the following three factors influenced their decision to return.

3.1.1. The Plight of Economic Challenges

Had it been that there was no lockdown, I’m sure I wouldn’t have been here. Of course, I have experienced attacks and robberies, and I had an accident, but I don’t rate them as my worst experiences because I believe these are just incidences that you can easily get through. But the period during lockdown was the worst (P8).

I came back home because things were not going as planned; I went there and got hit by Covid-19, and it was not how I planned it to be. And soon after Covid-19, it was not easy to get a stable, well-paying job because even employers were struggling. So, after working to settle my debts, I came back home to just try other things here…. financial challenges were there, you know, that period was not easy on most people, so I decided to come home and start afresh. I was not really scared of Covid-19, but I just thought, with the new waves that we kept hearing about, I thought, what if there is another lockdown? It would push me into other debts. So, I came home knowing my country would not completely have a lockdown; there would still be room to hustle (P14).

Before Covid, I had a live-in job, and I saved a lot. But when Covid-19 hit, my bosses told me they couldn’t continue to keep me, so it left me jobless, without a home. I had to start over building myself to look for a house. I started living in the location. It was a complete change (P12).

3.1.2. Fear of Dying in a Foreign Country

I first heard about Covid-19 when I was in SA. It was in other continents, and my first reaction when I heard was that I hoped Covid-19 wouldn’t come to Africa. But it didn’t take long before we heard it was in SA. We were scared that with the way Covid was spreading and killing people, we could die in SA. We were thinking that we should just go home. If anything, we should die at home (P5).

The fear of dying in a foreign country is scary for several reasons. Dying afar in the absence of close family and relatives could mean that they may not get a dignified, culturally acceptable burial. It could also mean that their entire journey, struggle, and life in general become meaningless as they may not be celebrated and remembered in a foreign land.

3.1.3. Lack of or Poor Integration in the Host Country

The notable challenges experienced in SA are the constant attacks by South Africans, you know those people don’t like to have migrants in their country. They just hated us, so sometimes they would start movements to send us back home; whenever they did that, we would not go to work. It was just challenging to live in peace with these people. South Africans don’t like migrants, so we didn’t really try to integrate with them. Of course, others are nice and kind. But we mostly associated with fellow Malawians for safety (P11).

Most bosses fear the employee will someday steal from them and run. So, they keep the passports to prevent them from leaving. However, some challenges happen because of language. Some foreigners struggle when communicating with their employers, which keeps them from expressing their grievances because they can’t communicate. Also, sometimes South African citizens attack foreigners whenever they have issues with their administration and government (P8).

I learned that having family around is the greatest blessing we should not take for granted. Most people were lonely during this period because we were asked to stay inside. But those with family and friends here in Malawi were better off (P12).

I learned that being in your own country is comforting during pandemics. Had it been that I was home during that time, I wouldn’t have gone through the things I went through (P14).

The three factors, economic hardships, fear of dying in a foreign land, and lack of community integration, independently and collaboratively influenced how migrants felt about staying in South Africa or returning to Malawi during the pandemic. Covid-19 exacerbated/compounded these conditions, thereby creating push forces that saw many migrants returning to their own country, where they felt safe, despite less economic prospects.

3.2. Domain 2: Travel/Transit

Traveling during a crisis increases vulnerability, particularly among migrants, a population that is already at risk of exposure to abuse, neglect, and lack of resources to sustain good health. Participants highlighted the following four factors contributing to increased vulnerability.

3.2.1. Corruption and Fear of Being Robbed

No, we were not safe since we were sleeping on the bus, so we were failing to be fully asleep because we were afraid someone might come on the bus. In Harare…in the middle of the night, we saw that some people were moving up and down the bus. Some of us were sleeping…there were other transporters who were not asleep; they woke us up and said, “All Malawians going home in this bus, wake up.” So, we woke up and realized those that were moving up and down wanted to steal from us (P9).

3.2.2. Closed Borders and Delays

The time I was coming back, it was a bit challenging because some borders were still closed, like in Zimbabwe. So, we couldn’t find a direct bus coming to this side. So, I used a minibus from Johannesburg to Maputo; then we boarded another bus from Maputo, which dropped us at a certain place; from there, we got another bus to Tete. From Tete, we got minibuses which were come to Dedza (Malawi). So, I left Johannesburg on Sunday Morning, and I got home on Thursday. So, you can just imagine that the journey wasn’t easy (P4).

We stayed for another 4 days (at the Malawian border) to have the goods cleared and our documents stamped. We were charged a lot of money to clear the goods. So, we started communicating with our customers to send money to clear their goods. (P6)

We traveled with the police from SA, who escorted us to a particular border, and from there, we got different police on each border. Police cars were in front and behind while our buses were in the middle. So, wherever we stopped, we had the police there. So, we were safe (P5).

3.2.3. Lack of Adherence to Covid-19 Mandates

Participants’ testimonies demonstrated that vulnerability increases the likelihood of being taken advantage of. Transporters preyed on desperate migrants and transported them in crowded conditions devoid of safety and protection from Covid-19 infection. One of them shared, “No, you can’t expect social distancing in the bus because the bus owners look to fill up all the seats to make profits” (P10). Others reported, “There was no social distancing in the bus…we were just at risk because we were not following social distance, or wearing masks, or using masks” (P4). Even those who took the risk of traveling on private transport echoed, “Social distancing was difficult. There were three of us in the truck. So, giving each other 1 m space was difficult” (P6).

3.2.4. Lack of Money, Food, Sleep, and Personal Hygiene

The fiscal crisis pre-departure and its impact continued during the participants’ journey to Malawi. As discussed under domain one, maintaining regular savings in a foreign land is always a challenge for migrants who tend to remit some of their earnings to their native countries to support families or establish income-generating projects of their own. The sudden loss of jobs because of the pandemic left many participants without enough money for basic needs such as transport, food, and housing. Many who chose to travel back to Malawi shared the sentiment of traveling without money, which increased their vulnerability. Most experienced hunger, lack of sleep, and challenges in maintaining personal hygiene that exposed them to health risks in addition to Covid-19. “We were not getting proper accommodation to sleep in, plus we were not bathing” said a participant (P4). As some spent all their money to pay bus fares, they were forced to travel without food. “As for me, I traveled without money; all the money I made, I had sent it home. The transporter, I only gave him transport money. So, he was not buying any food for me” (P3).

3.3. Domain 3: Return and Reintegration

Many participants experienced return and reintegration in three distinct ways—social reintegration, economic reintegration, and the contemplation of return to South Africa. While returnees felt welcomed by their families, they experienced a significantly worse economic situation that left them re-considering whether to stay or return to South Africa.

3.3.1. Social Reintegration

Family members were happy to see me, considering that I was in a foreign country during a pandemic; everyone was worried about our health in a foreign country. So, when I got home, they were happy to see me back alive. So, they were not worried that we might bring covid. They were simply happy to see us (P5).

However, some participants expressed that social reintegration was not easy as they lost contact with former friends, people moved out of their neighborhoods, or family members established their own new families and children.

3.3.2. Economic Reintegration

Business is hard in Malawi because I think only 20% of people in Malawi have good jobs, and about 20% are doing good businesses, so that means only a few people have access to money. But the rest are struggling. So, it’s hard to do business. For example, if I order clothes and (sell) them to people on credit when month end comes, most people will only give a tiny fraction of the total amount, so it’s hard to raise more capital because when that money comes, it’s easy to spend it since it’s a tiny fraction. (P4)

Further, the lack of access to capital was worsened by mistrust toward returning migrants by local community financial groups as they feared that returnees might circle back to South Africa without paying back borrowed money. One participant explained this dilemma, “When I go in savings groups to borrow some money, they doubt me, fearing that I might run off to SA. So, since I am struggling with capital, sometimes I feel like I should try SA again” (P3).

3.3.3. Prospects of Returning to South Africa (Circular Migration)

Currently, I don’t think I would want to go back because I am trying to make it work here in my country, but if I see that I’m struggling, I’ll definitely go back. It is better to go and work as a garden boy in SA and make enough money to take care of my family than stay in my country but struggle. (P10)

From my experience in SA, I wouldn’t advise anyone to go to SA; I can’t even allow my children to go to South Africa. Because I felt like I was suffering in SA, I was not free at all. So, I wouldn’t advise anyone to go there. I would rather encourage them to start a business here in Malawi. (P7).

3.4. Domain 4: Potential Solutions to Reduce Vulnerability

In addition to sharing their experiences of returning home during Covid-19, most participants provided suggestions for what they felt would decrease their vulnerabilities during their journeys and promote their social and economic integration and success. Suggestions fell into two main areas—government- and migrant-related considerations.

3.4.1. Government-Level Interventions

I think countries should just express humanity and help everyone regardless of where they are coming from. The SA government was very discriminatory during this period, they only looked after their citizens when we were all suffering. They should have been considerate of everyone (P14).

They are in embassies to represent us, so if they don’t help us where else can we get the help? We can’t expect people in SA to help us when we are failing to help ourselves. The SA government people were helping their citizens. Some churches tried, though, to give help and support to everyone. They (the Malawian government) should have been providing preventive equipment so that people don’t contract Covid-19. They should have also provided food and shelter for those who were struggling because we had people who were failing to pay rent and were chased out of their houses. (P6)

On a national level, I think it would have been helpful if the Malawian government and South African government joined forces to move those who were completely stranded during the lockdown (P10).

Participants specifically suggested that the two governments should have provided free transportation for returnees, financial support to start-ups or businesses, and promoted peace and cooperation between Malawians and South African communities, especially during such a global crisis. Most participants agreed that it is the Malawian government diplomats’ mandate to engage the South African government to take collaborative actions to help migrants. One participant shared, “On a national level, I think it would have been helpful if the Malawian government and South African government joined forces to move those that were completely stranded during the lockdown” (P10).

3.4.2. Migrant-Level Interventions

As Malawians, we have good land to use to develop our livelihoods. However, I can also ask the people what they were each doing in SA so that we can design programs for each individual based on their experiences in SA (P7).

Participants also suggested creating returnee support groups, like migrant support groups in South Africa, to facilitate collaboration and ensure financial security among Malawians. There should be groups; like in South Africa, all the Tumbukas (people from northern region of Malawi) in Cape Town make contributions as a group. They are an institution that opened an account and saved money there. I know that most of them did not struggle during the pandemic because of those funds. They have meetings; if you miss them, you get fined. They pay ZAR100 per person every month. It is a group setting with rules. If nothing has happened during the year that requires using said funds, they divide the money amongst the group members at the end of the Year. They openly communicate (P15).

Participants also advised that returnees should plan to try their best in Malawi rather than focusing on SA. But all agreed that government support and self-preparation are equally important to reverse the socioeconomic hardships experienced by Maliwan migrants.

4. Discussion

The Covid-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted migration trends and the experiences of migrants worldwide, especially during the peak of the pandemic when economic hardship and travel restrictions were crucial factors. This study explored unique patterns observed among Malawian migrants in South Africa, which saw an unusual voluntary return to their country of origin during the Covid-19 pandemic. The findings, therefore, provide an in-depth outlook of Malawian migrant experiences by examining peculiar determinants of migration decisions across different phases of the migration cycle: departure, transit, and reintegration.

The pre-return or departure phase is a critical period in the migration cycle, often marked by significant decision-making influenced by various push and pull factors [28]. The decision to return to Malawi, though voluntary, was largely driven by economic hardships exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Many migrants faced job losses and reduced income, making it difficult to sustain their livelihoods in South Africa [38]. Similar trends with other migrants were observed by Ho [39]. The fear of contracting Covid-19 and dying in a foreign land also played a crucial role in their decision to return. The existing literature highlights the role of emotional and psychological factors in determining migration [40]. Additionally, previous studies have highlighted the importance of social integration in migrant well-being and its impact on migration decisions [41]. In this study, the absence of strong community ties and support networks in the host country, coupled with persistent xenophobia, made the prospect of returning home more appealing despite the economic difficulties in Malawi. These findings align with previous research highlighting the vulnerabilities of migrants, where economic and social factors are significant determinants of migration decisions [11, 12].

The travel and transit phase of Malawian migrants returning from South Africa during the Covid-19 pandemic was marked by several significant challenges that heightened their vulnerabilities. This phase, often regarded as a critical juncture in the migration process, was reported to be influenced by corruption, logistical delays, and safety concerns. These factors had profound implications, depleting the already limited financial resources and instilling a pervasive fear of harassment during the journey. Hence, contrary to common expectations, the journey back home was not without challenges, which explains why many migrants consider returning only as a last resort [42, 43]. These encounters also highlight systemic issues within border control and enforcement agencies in the region that exacerbate the hardships faced by migrants [44, 45]. Notably, the timing of their return did not help the situation as Covid-19 travel restrictions had led to border closures and delays in admission into certain regions [46, 47]. These delays not only extended the duration of their travel but also exposed these migrants to greater risks of Covid-19 infection and other vulnerabilities, as spending nights inside buses without adequate facilities increased susceptibility to both physical and emotional health issues. Adverse conditions during immigration transits are a well-documented experience among migrants, typically as they leave their home countries [48].

However, this study uniquely found that such conditions are also prevalent during their return. The lack of adherence to Covid-19 safety protocols during transit further heightened their vulnerability to the Covid-19 infection as buses were frequently overloaded and Covid-19 prevention practices rarely enforced. This situation resulted in a heightened risk of Covid-19 transmission among migrants, many of whom already had limited access to healthcare [38]. These experiences underscore the systemic issues within migration governance, where bureaucracies and inadequate protection mechanisms exacerbate the hardships faced by migrants during crises [21, 49]. Migrants who were fortunate to secure spots on government-provided buses shared a starkly contrasting experience where better seating arrangements and the presence of police escorts ensured safety and comfort. These narratives, therefore, highlight the importance of coordinated efforts and support from both government and international agencies in significantly mitigating the risks and challenges faced by migrants during transit [50, 51].

Upon returning to Malawi, migrants experienced a mixed reception. While familial and societal reintegration was generally positive, with many feeling a sense of relief and safety at home, economic reintegration proved challenging. However, in Asia, in addition to the economic reintegration challenges, the returning migrants were received with apprehension as they were seen as Covid-19 infection carriers and spreaders [52]. The reason for this apprehension could be related to the fact that Asian countries were severely affected by the pandemic unlike most African countries including Malawi, which only registered a few Covid-19 cases. The literature on the experiences of returned migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa suggests that the lack of employment opportunities and capital for business ventures leave many struggling to support themselves and their families [53] Similar experiences have been reported in Asia [39, 52]. Among our study participants, this economic instability often led to contemplation of returning to South Africa, highlighting the cyclical nature of migration driven by economic necessity. These findings echo the broader literature on return migration, which emphasizes the importance of sustainable reintegration support to prevent repeated cycles of (circular) migration [54].

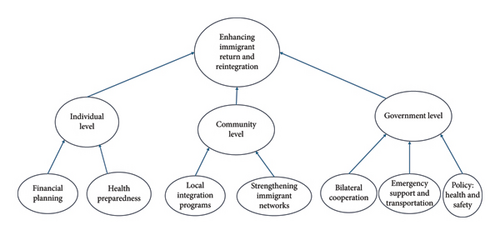

4.1. Reducing Vulnerability and Enhancing Re-Integration

Participants suggested several measures to mitigate the vulnerabilities experienced during their migration journey. At the government level, there was a call for more proactive and coordinated efforts between the Malawian and South African governments to support migrants, including providing transportation, food, and shelter during crises. Additionally, participants emphasized the importance of having savings and participating in community-based financial support groups to buffer against future economic shocks. These narratives highlight the need for comprehensive migration policies that address both immediate needs during crises and long-term reintegration support [54–56]. As host countries explore ways to minimize the burden of immigration on their limited resources, our study findings suggest a need for more robust systems to enhance return migration in ways that make the potential for return more attractive than the possibilities of staying. A collaborative approach between governmental and non-governmental actors could bolster this process. In line with global recommendations [28] and participant narratives, this study proposes a three-level approach (Figure 2) to addressing migrant re-integration: individual-, community-, and government (home and host countries)-level interventions.

These three levels of intervention could synergize. There are examples on individual and community level solutions that were reported by these migrants. However, these were done without thinking of the possibility of such crises. These mostly focused on illness and funeral support among migrants [38, 57]. The Covid-19 crisis serves as a wake-up call for many of the migrants for initiatives such as individual savings and establishment of immigrant networks. This could potentially provide migrants with safe, comfortable, and potentially less costly means of returning to their home countries while creating opportunities for networking, community relations, and economic planning. Such programs could support returned migrants for a transition period until they can fit well into their new communities. This strategy will ensure that returning migrants are likely to stay in their home countries than aim for other immigration opportunities, which may create similar challenges they went through. Governmental-level interventions have been very minimal and based on demand from migrants. However, this return process created an awareness on the need to have more deliberate policies in place to support migrants in such crises. This paper will inform government stakeholders on the fundamental issues that require government attention, which could lead to the formulation of policies and guidelines that could support migrants in future pandemics. The paper further closes the literature gap, especially on challenges faced by returning migrants during transit to, and reintegration in, their home countries, especially during a crisis [52].

4.2. Theoretical Implications

Theoretically, this research highlights the intricate dynamics of decision-making during crises, offering insights into how migrants weigh economic, social, and psychological factors during an unprecedented global pandemic—Covid-19. The findings offer insights into migratory experiences in a scenario where all the three spaces, home countries, transit countries, and destination countries, are impacted by a global crisis and how migrant navigate the complexities arising from the situation. Most importantly, the study has two major contributions for future theoretical models. First, it underlines the fact that migration during a global crisis is not a linear process but a complex and cyclical process that involves temporal as well as sustained socioeconomic, health, safety, policy, and integratory factors. Second, the study extends the concept of transnationalism by emphasizing the role of “third-places”—transit countries—and how these experiences influence both integration in host countries and reintegration in home countries. The findings suggest a need for theoretical models to account for the multi-layered impact of crises on migration trajectories and the cyclical nature of migration decisions.

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Research

The major limitation of the study is that due to lengthy delays in getting ethics approval in Malawi, the research was conducted much later between October and December 2022, which was almost 1.5 years after the peak of Covid-19. By this time, most people who had returned to Malawi due to Covid-19 were considering returning or had returned to South Africa due to the economic hardships in Malawi. With an extended period, participants may have forgotten some facts and details about their experiences returning to Malawi. Timing in the context of an evolving pandemic is a critical issue that affects the timely dissemination of results and development of interventions. For future research, studies of this nature, conducting in a fluid environment should make effort to engage relevant research approving entities ahead of time. Additionally, the study’s use of purposive and snowball sampling, while effective in enhancing participation and fostering open discussions, may have introduced bias and limited the representativeness of the study sample. Insights gleaned from this study can inform future migration research and practice during a pandemic.

5. Conclusion

The experiences of Malawian migrants returning from South Africa during Covid-19 reflect the complex interplay of economic, social, and psychological factors influencing migration decisions. While returning home provided a sense of safety and familial support, economic challenges remain a significant barrier to successful reintegration. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated efforts at both policy and individual and community levels to ensure the well-being and sustainable reintegration of returnees. Future research should focus on longitudinal studies to track the long-term outcomes of returning migrants and the effectiveness of implemented support measures. An exploration of stakeholder perspectives would also enrich the existing literature on migration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the University of Missouri South Africa Educational Program (UMSAEP).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of participants during the study. The support we got from the University of Missouri South Africa Education Program is appreciated.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Because the primary data for this manuscript include in-depth interviews, they are not included in any online repository. However, the researchers are willing to share such data upon request and signing of a data release agreement.