The Scope, Range and Use of Voluntary Sector Specialist Sexual Violence Services in England: Findings and Recommendations From a National Study

Abstract

Sexual violence is a global problem with significant individual and societal health and social costs. Services that support victim-survivors of sexual violence across a range of sectors are crucial. This study investigated the scope, range, funding and commissioning of voluntary sector specialist (VSS) sexual violence services in England and victim-survivors’ experiences of using such services. The specialist voluntary sector plays a pivotal role in providing crisis and longer-term support to victim-survivors. However, there is limited empirical evidence about the scope, range and use of VSS provision, or what victim-survivors value and want from services. The aim of the study was to address this gap and provide much-needed evidence to inform the VSS sector nationally. This co-produced study included five co-researchers and one co-applicant with lived experience of sexual violence. There were three empirical phases: (1) exploratory interviews with commissioners and service providers and focus groups with victim-survivors; (2) national survey of service providers and commissioners; (3) in-depth case study analysis in four areas of England. The purpose of this paper is to synthesise the findings from each of these phases and map them onto a conceptual model, encompassing six themes: the complex and precarious funding landscape; the challenge of competition for funding and contracts; the role of partnership working; the pressured environments within which VSS services work; the different roles, scope and eligibility of voluntary and statutory services within an area; the ways services are delivered, underpinned by services’ values and philosophies. The study provides new, empirical insights into how these arrangements affect those connected with the services—namely, staff, volunteers and victim-survivors. The paper sets out 14 recommendations for all parties involved in the funding and commissioning of specialist services, including commissioners, grant funders and VSS organisations in England.

1. Introduction

Sexual violence (SV) is defined as any sexual act or attempted sexual act that takes place without consent or against a person’s wishes [1]. One in three women globally experiences physical and/or SV perpetrated by an intimate partner [2]. The individual and societal costs of SV—impacting on health, relationships and work life—are significant and well-known. Rates of posttraumatic stress disorder are higher for SV compared with other traumatic events [3]. Depression, anxiety, suicide, self-harm, alcohol/drug abuse and sexually transmitted infection rates are all high [4, 5], and impacts on mortality have been found [6]. Some impacts can be passed on to the next generation [7]. Therefore, the burden on individual victim-survivors, health systems and wider society is likely to be excessive if these impacts remain untreated. Indeed, it is important to emphasise that victim-survivors can, and do, move forward from SV and that effective support services are central to the process of recovery. This article focuses on such support services, specifically those situated within the voluntary sector in England. Complementing existing evidence generated by voluntary sector specialist (VSS) services, this study is the first national empirical study that synthesises evidence about the sector, on how SV services are organised, funded and commissioned. It captures the experiences of staff and volunteers working in the sector and, crucially, how services are used by victim-survivors. The paper provides a holistic overview and synthesis of the study findings, drawing them together in one location.

1.1. Organisation of Voluntary Sector Specialist Services in England

VSS services in England are typically grassroots nonprofit organisations that provide counselling/therapy, helplines, practical support and advocacy. VSS services frequently provide referral/signposting into and through other local and national services or processes for victim-survivors. Some services are female-only, reflecting the understanding that women make up more than 80% of victim-survivors who report SV (https://rapecrisis.org.uk/get-informed/statistics-sexual-violence/). It is not uncommon for VSS services to be grounded in feminist philosophies, even if they support victim-survivors of all genders. Principles and philosophies that sit alongside a feminist perspective, such as that of being trauma-informed and survivor-centric, are all valuable elements of VSS service support provision. Victim-survivors can access these services via self-referral, referral from health and social care professionals [8], and/or via referrals from Sexual Assault Referral Centres (SARCs). SARCs are National Health Service (NHS) funded centres that provide medical and sometimes practical support, as well as collection of forensic evidence for criminal justice purposes following sexual assault.

The funding and commissioning of VSS services in England have become increasingly complex due to changes in the structure and funding of health [9] and criminal justice services. Funding for VSS services typically comes from charitable bodies plus local and national statutory sources, via health, local governing authorities and criminal justice organisations. To illustrate the complexity of the funding and commissioning picture, NHS England commissions medical aftercare and short-term therapeutic support for victim-survivors. This commissioned work is often carried out by or in partnership with SARCs. Some Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) also commission therapeutic support (e.g., short- to medium-term counselling) for some groups of victim-survivors; however, the commissioning of such services by ICBs varies widely, and in many areas of the country, therapeutic provision for victim-survivors is subsumed under ‘generic’ mental health support. The Ministry of Justice manages the Rape and Sexual Abuse Support Fund (RASASF) in England and Wales. This is a source of funding for, but not limited to, the funding of specialist Independent Sexual Violence Advisors, counselling and therapeutic support, helplines, etc. These services are for recent and nonrecent victim-survivors. The Ministry of Justice also has devolved many key commissioning responsibilities to local Office for Police and Crime Commissioners, who are one of the primary commissioners of specialist services of VSS organisations across England and Wales. Intersecting these primary commissioning routes, some local authorities commission or grant-fund some services (relating, for example, to their duties to support children ‘at risk’ or suffering harm, or as part of their public health duties). The Home Office Violence Against Women and Girls Specialist Fund also offers funding that VSS organisations can competitively bid for, with a focus often on themed calls and innovative projects (rather than sustaining existing services).

This creates a complex network of responsibilities at a local level. It also compounds VSS service difficulties in establishing and maintaining relationships, particularly with public sector providers, not least because there is a prevailing attitude that VSS services are ‘amateur’ and small scale [10] compared to statutory providers.

In some areas, new and untested local models of collaborative commissioning have emerged, such as contracting with a lead provider for a network of local services, which may include VSS providers [11]. One consequence is that the previous model of a mixed economy of provision for victims, which included smaller organisations who are adept at meeting the needs of specific groups at the local level, has become untenable under the drive towards a free-market model and competitive tendering [12]. In other areas, VSS providers are taking the initiative and collaborating between themselves, moving to common standards and seeking to join up services locally via partnerships and consortia [13]. However, little is known about their effectiveness and how they might impact services for victim-survivors. Anecdotally, the sector reports a tendency towards short-termism in funding opportunities and a lack of understanding by some commissioners of the VSS sector’s role and contribution, including confusion regarding which services are responsible for what [11].

In addition to academic evidence gaps regarding funding and commissioning within the sector, we know relatively little about what victim-survivors are currently receiving from VSS services nor the perceived impacts of such services. Where studies do exist, e.g., a national survey with 395 victim-survivors [14] and the Independent Inquiry into Childhood Sexual Abuse [15], we understand that victim-survivors want a choice of specialist support that they can access locally and in a timely way, from well-connected and joined-up services. The specialism of VSS support was noted in one study as being vital in setting the sector apart from how NHS therapy was experienced [16].

Studies comparing VSS services with statutory provision have reported a preference for VSS services, with these rated more highly across counselling and psychotherapy, and other forms of support [10, 16, 17]. Such a preference reportedly comes from the independence, flexibility, empowerment and specialism of VSS provision [5]; elements statutory services have been criticised for not providing [11]. Not only can victim-survivors become dissatisfied from attempts to seek support from services but they can also be secondarily traumatised by institutions through the betrayal arising from inappropriate attempts at support [15, 18]. The study reported in this article was designed to address these empirical gaps by informing the evidence base about how VSS services are funded and commissioned. Importantly, it provides new insights into how these arrangements affect those connected with the services—namely, staff, volunteers and victim-survivors.

2. Methods

The research aimed to develop a comprehensive national understanding of VSS services for victim-survivors in England. We undertook an analysis of the range, scope and funding of services, service models and approaches, service linkages and commissioning arrangements. This was an NIHR-funded study entitled PROSPER: exploring the suPorting Role Of SPecialist sERvices.

2.1. Theoretical Framework

- •

Flatter organisational structures with less distance and distinction between senior or decision-making staff and those on the front line.

- •

Closeness to communities.

- •

Being mission-led and driven by core values and purpose.

The rationale for drawing on this theory was its potential to help understand and explain the prominence and distinctiveness of the voluntary sector in providing support to victim-survivors of SV. The theory also helps to surface the unique features (and perceived limitations) that shape their response to their client group. During the study, we revisited this theoretical framework frequently, reflecting on how it was shaping and informing our methodologies and subsequent analyses. We used the theory as the guiding framework for data synthesis, with this flexible and reflexive use of theory being advocated by Bradbury-Jones and colleagues [21].

2.2. Ethics Approvals

The study was subject to the following ethical approvals: The University of Birmingham Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics ethics committee in February 2020 (ERN_19-1152A) and October 2020 (ERN_19-1152B). Research governance approval was granted by the Health Research Authority (HRA) and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) in January 2021 (REC reference: 20/HRA/6042). The Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) (Ref: RGE201005) and the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services approved sharing the survey weblink(s) among their members.

All participants provided informed consent, and no ethical issues arouse across the duration of the project. We sought multiple opportunities throughout the study to ensure equality and diversity in our samples. We discuss this further in the limitations section.

2.3. Study Design

The study was divided into three empirical phases: Phase 1: Exploratory interviews with commissioners and providers and focus groups with victim-survivors. Phase 2: National survey of service providers and commissioners. Phase 3: Case study analysis of four areas in England. The study protocol outlining these phases was published at the beginning of the study [22]. Primary data from the different phases are beginning to be published elsewhere, specifically from Phases 1 [23] and 2 [24]. These individual-phase papers are important, but the aim of this current paper is to provide an overview and synthesis of data from across the different phases, located in one place. To avoid duplication, we have not presented primary data in this article. We present the overall empirical findings from the study, along with the overarching themes and recommendations arising from the work.

Co-production was built into the study from its inception; initially through the development of the research proposal with lived-experience co-applicants, plus the addition of five lived-experience co-researchers working on the study. The co-researchers worked with the academic team on data collection for the victim-survivor interviews (see below), data analysis (of the survey and interviews) and dissemination activities. This highly participatory methodology was intended to amplify the voices of victim-survivors; enhance the collection of meaningful data; empower victim-survivors who were participating in the research; and promote learning and development of new skills among all team members.

2.3.1. Phase 1: Exploratory Interviews With Service Providers and Commissioners and Focus Groups With Victim-Survivors

The aims of Phase 1 were to develop understanding of the principal issues shaping the delivery, funding and commissioning of VSS services and the unique features of these organisations. Further, to use the findings to inform the development of three national surveys (Phase 2) to map the provision, funding and commissioning of specialist SV services.

Two experienced, female qualitative researchers (C.G. and L.I.) carried out interviews with (a) senior practitioners of VSS services (n = 13), (b) commissioners of SV services (n = 8) and (c) providers (n = 2) from the statutory sector who worked in SV services. We also carried out two focus groups with female (n = 9) and male (n = 5) victim-survivors and one telephone interview with a female victim-survivor.

Interviews and focus groups explored the strengths and limitations of VSS services; the relationships, pathways and comparative differences between voluntary and statutory sector services; current funding and commissioning arrangements (including areas where there has been change/continuity); victim-survivors’ experiences of accessing voluntary and statutory sector services; perceived differences between services; suggestions for improvements. The transcripts were analysed thematically, drawing on Billis and Glennerster’s theory of the comparative advantages of the voluntary sector (as described). Table 1 presents a summary statement of the key findings from Phase 1, which subsequently informed the design and development of the national surveys in Phase 2 and the case study analysis of Phase 3.

| Phase 1 findings highlighted how the specialist nature of VSS services is highly valued by victim-survivors. Such services provide a dedicated, protected environment for victim-survivors. It is an environment in which shame and stigma are understood and challenged. Victim-survivors benefit from (and prefer) the independent and needs-led approach of the voluntary sector, in comparison to the statutory sector. For staff, there are challenges of working in an environment that is characterised by high caseloads, increasing demand and higher client need/complexity. This is accompanied by the challenges of competing for funding and contracts and the insecurities generated by short-term and innovation-focused funding. As a result of such pressure, practitioners were reported to be leaving VSS services, leading to loss of specialism and expertise. VSS services expressed concern that the move toward joint-funded and large contracts is likely to favour larger, often generic providers. This threatens the survival of smaller, bespoke VSS services who provide valued support to victim-survivors. However, good relationships existed between many statutory and voluntary sector services and there were examples of innovation and close partnership working. In some cases, short-term and/or innovation-focused funding resulted in ‘good’, established VSS services struggling to survive. The associated precariousness negatively affects staff morale and retention and can undermine sector leader’s ability to work in a strategic and creative way |

2.3.2. Phase 2: National Survey of Service Providers and Commissioners

We designed and administered three online surveys for commissioners of services for victim-survivors, VSS service providers and SARCs. The surveys were designed to enable comparative analysis between the three participant groups on several key themes, including views of funding and commissioning, the strengths of VSS services and underrepresentation of victim-survivor groups. The surveys were available for completion electronically between January and June 2021. Once data collection was complete, two members of the co-researcher team were involved in the analysis process (L.H. and L.P.). Twelve surveys were returned from SARCs, 54 from VSS providers and 34 from commissioners. Table 2 outlines the personal (sociodemographic) and professional (role-related) characteristics of respondents, and Table 3 provides a summary of the survey results.

| Characteristic ∗ | Group | SARCs | VSS providers | Commissioners |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| All responses | 12 | 54 | 34 | |

| Role | Manager | 11 (91.7) | 13 (24.1) | 12 (35.3) |

| CEO | — | 33 (61.1) | — | |

| Senior practitioner or commissioner | 1 (8.3) | 1 (1.9) | 7 (20.6) | |

| Policy officer | — | — | 15 (44.1) | |

| Other ∗∗ | — | 4 (7.4) | — | |

| Time in current post | < 12 months | 1 (8.3) | 5 (9.3) | 2 (5.9) |

| 1–5 years | 9 (75.0) | 29 (53.7) | 20 (58.8) | |

| 6–10 years | 2 (16.7) | 11 (20.4) | 10 (29.4) | |

| 11–15 years | — | 2 (3.7) | 2 (5.9) | |

| 16–20 years | — | 4 (7.4) | — | |

| 21+ years | — | 3 (5.6) | — | |

| Time in specialist SV services or commissioning | < 12 months | 1 (8.3) | 2 (3.7) | 2 (5.9) |

| 1–5 years | 6 (50.0) | 12 (22.2) | 12 (35.3) | |

| 6–10 years | 2 (16.7) | 18 (33.3) | 11 (32.4) | |

| 11–15 years | 2 (16.7) | 7 (13.0) | 7 (20.6) | |

| 16–20 years | 1 (8.3) | 5 (9.3) | 2 (5.9) | |

| 21+ years | — | 10 (18.5) | — | |

| Self-reported gender | Male | — | 5 (9.3) | 8 (23.5) |

| Female | 10 (83.3) | 49 (90.7) | 25 (73.5) | |

| Age group ∗∗∗ | 18–40 | […] | 13 (24.1) | […] |

| 41–50 | […] | 13 (24.1) | 13 (38.2) | |

| 51+ | […] | 28 (51.9) | 14 (41.2) | |

| Ethnic group (self-reported) | White British | 9 (75.0) | 40 (74.1) | 30 (88.2) |

| Other ethnicity | […] | 13 (24.1) | […] | |

- ∗Percentages may not total 100 due to missing responses.

- ∗∗Director of operations (n = 3), trustee (n = 3) and business manager (n = 1).

- ∗∗∗Cells reporting personal characteristics with fewer than five respondents have data suppressed, denoted by […], to preserve anonymity.

| The survey results supported the findings from Phase 1. Survey respondents reported that there is significant variation in VSS service scope, organisation, funding and delivery arrangements, characterised by a complex patchwork of VSS services that often work closely with each other to support victim-survivors. Service configurations may reflect a legacy of historical funding and commissioning arrangements, but there is evidence of significant innovative practice. |

| Many VSS services offer support that no other services do, and often to underrepresented groups, for example, sex workers. However, there is a need to expand further the support for some underrepresented victim-survivors, e.g., those who are minoritised. Overall, there is substantial unmet need within the sector, which restricts responsiveness to clients and waiting lists are growing over time. Service users present with increasingly complex trauma, but there is restricted duration of support. This leads to concerns among practitioners regarding the ability to meet the needs of some victim-survivors. The funding landscape is complex and precarious. Most services rely on multiple funders and work with a variety of commissioners. Services are competing for the same funding, which is both inconsistent and unstable. High staff turnover and stress are evident within the sector |

2.3.3. Phase 3: Case Study Analysis

Phase 3 involved an in-depth investigation of four areas in England using a case study approach. We drew on Stake’s [25] delineation of case studies, where issues are described as ‘complex, situated (and embodying) problematic relationships’ [25]. We explored the role of VSS services, their links with other local services and the funding and commissioning arrangements that underpin them. We also explored victim-survivors’ views and experiences of (not) accessing services across their life course. Extensive exploratory work was carried out, establishing relationships with key stakeholders in each site area prior to participant recruitment. Within the case study sites, data were drawn from three primary sources: (1) Documentary analysis (e.g., service mission statements, local evaluations of services, publicly available financial records and local service specifications); (2) interviews with staff (e.g., those working in VSS services, commissioners/other funders, NHS/local authority staff); and (3) interviews with victim-survivors, drawing on techniques of narrative interviewing.

- •

The exploratory Phase 1 interviews.

- •

Recommendations from the study steering committee and co-applicants who included senior members from VSS umbrella organisations who understood their member services and familiarised us with local funding/commissioning tensions, unique approaches to service delivery, etc.

- •

Publicly available data from the Charity Commission (and financial information available to year end March 2020) and the websites of VSS services.

- •

Demographic data drawn from the 2011 Census (with estimated population projections used for some areas) and the 2019 Indices for Multiple Deprivation Index (IMD) as organised by upper tier local authorities.

We selected the final four sites based on achieving maximum geographical variation across England (north/midlands/south); population density (urban/rural); demography (disadvantaged/affluent/mixed); and diversity (high/low minoritised populations). However, our principal criterion for site selection was to achieve variation [26] in the sites’ VSS service models and their underpinning funding and commissioning arrangements. Sites were defined geographically by city and/or county boundaries or groups of neighbouring districts. Data collection began in the autumn of 2021, and participants from three main participant groups—commissioners/funders, practitioners and victim-survivors—were interviewed by the end of April 2022. Approximately half of the victim-survivor interviews were co-facilitated by a co-researcher and a member of the academic team. Table 4 outlines the recruitment figures across the participant groups, showing the demographic spread. Table 5 presents a summary of the case study findings.

| Demographic category | Practitioners (voluntary) | Practitioners (statutory) | Funders/commissioners | Victim/survivors | Total participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 18–24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 12.9 | 4 | 5.63 |

| 25–34 | 2 | 8.70 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 33.3 | 7 | 22.6 | 13 | 18.3 |

| 35–44 | 4 | 17.4 | 1 | 20 | 2 | 17.0 | 8 | 25.8 | 15 | 21.1 |

| 45–54 | 6 | 26.1 | 3 | 60 | 5 | 41.7 | 5 | 16.1 | 19 | 27.0 |

| 55–64 | 9 | 39.1 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 22.6 | 17 | 23.9 |

| 65–74 | 1 | 4.35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.41 |

| Missing data | 1 | 4.35 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.82 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 20 | 87.0 | 3 | 60 | 8 | 66.7 | 18 | 58.1 | 49 | 69.0 |

| Male | 2 | 8.70 | 2 | 40 | 3 | 25 | 11 | 35.5 | 18 | 25.3 |

| Nonbinary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.23 | 1 | 1.41 |

| Missing data | 1 | 4.35 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.33 | 1 | 3.23 | 3 | 4.23 |

| Transgender ∗ | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 21 | 91.3 | 5 | 100 | 11 | 91.7 | 29 | 93.5 | 66 | 93.0 |

| Missing data | 2 | 8.70 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.33 | 2 | 6.45 | 5 | 7.04 |

| Sexuality | ||||||||||

| Bisexual | 2 | 8.70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6.45 | 4 | 5.63 |

| Gay | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6.45 | 2 | 2.82 |

| Heterosexual | 19 | 82.6 | 5 | 100 | 11 | 91.7 | 22 | 71.0 | 57 | 80.3 |

| Lesbian | 1 | 4.35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.41 |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9.68 | 3 | 4.23 |

| Queer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6.45 | 2 | 2.82 |

| Missing data | 1 | 4.35 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.82 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Black# | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 19.4 | 6 | 8.45 |

| British Asian± | 1 | 4.35 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 17.0 | 2 | 6.45 | 5 | 7.04 |

| White∧ | 16 | 70.0 | 5 | 100 | 8 | 66.7 | 21 | 67.7 | 50 | 70.4 |

| British/European§ | 5 | 21.7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.33 | 2 | 6.45 | 8 | 11.3 |

| Missing data | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.82 |

| Disability ∗∗ | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2 | 8.70 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 17.0 | 18 | 58.1 | 22 | 26.8 |

| No | 20 | 87.0 | 5 | 100 | 9 | 75.0 | 13 | 41.9 | 47 | 70.4 |

| Missing data | 1 | 4.35 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.82 |

- Note: Participant totals: practitioners (voluntary) = 23. Practitioners (other) (including NHS/SARC, etc.) = 5. Funders/commissioners = 12. Victim/survivors = 31. Total = 71.

- ∗This question asked whether the participant does or has ever identified as transgender.

- ∗∗This question asked about any kind of disability—mental or physical, learning differences and/or long-term conditions.

- #Including Black African and Black Zambian.

- ±Including British Pakistani, and White Asian, Asian British and Indian.

- ∧Including White British.

- §Including White Polish, White Ukrainian, White European, British Roma, Mixed British, Irish.

| The case study analysis highlighted the need for greater recognition of the unique value of independent, VSS services in providing flexible and responsive support to victim-survivors. Trauma-informed and victim-focused approaches are pivotal, which represent the voices of victim-survivors. There needs to be a genuine commitment by services to work with victim-survivors to co-produce services to avoid re-traumatisation. This phase highlighted how victim-survivors are not always aware of the VSS services available to them. We found that the ‘jigsaw’ of services across geographical areas can be difficult for victim-survivors to navigate. Referral pathways between services need to be clearer and more effective. Partnerships appear to work well in terms of connecting VSS services and statutory (e.g., NHS) services with each other and with commissioners. They offer a layer of support, accountability and structure to existing ‘good’ working relationships, with potential to raise the profile of sexual violence across an area. However, relationships between services can break down when there is competition over funding provision. Long-term sustainable funding for the sector is required. There was considerable variation between commissioning and funding arrangements across the case study sites, reflecting in part the evolution of working relationships, shifting local needs and the degree to which support for sexual violence services was (or was not) considered a ‘priority’ area. |

2.4. Data Synthesis

Synthesis of data from the different phases was led by the lead author and verified through several iterations with the rest of the team until consensus was achieved. The first part of the process involved a deductive approach [27] by using the broad statements that were held within the data as the starting point and making sense of them with reference to the specific details of our theoretical framework. In practice, this involved taking the findings from each phase and mapping them onto the theoretical framework [19], seeking the closet fit to each of the constructs. Once this stage was complete, verification and agreement with the wider team took place, resulting in no further revisions to the framework. Table 6 sets out an overview description of each theme and linkage to findings within each of the three study phases. The table does not provide an exhaustive account of the links between themes and the empirical data; rather, it intends to map how the study’s empirical findings support the key, over-arching themes.

| Key theme | Thematic overview | Links to each phase (key findings/themes) |

|---|---|---|

| The complex and precarious funding landscape | Funding for VSS services is not secure or sustainable. Services rely on a complex mixture of contracts, grants and, increasingly, independent fundraising. The nature of these funding streams undergoes constant change. This precarity creates vulnerability in terms of the longevity of vital services | Phase 1: Funding issues |

| Phase 2: Consequences of funding/commissioning arrangements | ||

| Phase 3: Arrangements for funding and commissioning | ||

| The challenge of competition for funding and contracts | Public sector bodies’ competitive tendering processes require that VSS services bid for contracts, which can put them in opposition to other local and/or specialist services. VSSs have developed considerable expertise in developing and engaging with commissioning processes but the practice is often relationship-based and characterised by precarity. Knowledgeable and committed commissioners can play a key role in making these processes and practices work in a way that benefits local services and populations | Phase 1: Consortia, collaboration and competition |

| Phase 2: Service funding; service commissioning | ||

| Phase 3: Arrangements for funding and commissioning | ||

| The importance and success of partnership working with organisations | Partnerships between VSS organisations (formal and otherwise) are often time-intensive to establish but can facilitate the pooling of expertise, institutional knowledge and resources. This can enable VSSs to ‘compete’ against larger providers and/or for large-scale (i.e., longer, higher award) contracts. They can also support timely and joined-up responses. For example, at a local level, partnership working between organisations (referral pathways, collaborative working, sharing of knowledge) can play a key role in improving what is often a difficult and long process for victim-survivors’ seeking the right support at the right time | Phase 1: Co-production and partnership in the commissioning process |

| Phase 2: Partnership working | ||

| Phase 3: Range, scope and funding of VSS services | ||

| The pressured environments within which VSS services work | In the context of managing multiple strands of short-term funding and/or contracts (including monitoring and reporting requirements) and increasing demand for services (e.g., waiting lists, increased ‘complexity’ of clients), senior staff are often navigating multiple strategic and operational demands with limited support. This context also affects practitioners, many of whom are employed on insecure contracts. It is important to note the gendered nature of precarity in a female-majority workforce | Phase 1: Consortia, collaboration and competition |

| Phase 2: Working with Commissioners | ||

| Phase 3: Range, scope and funding of VSS services | ||

| Different roles, scope and eligibility of voluntary and statutory services within an area | Victim-survivors often do not know how or where to access support, or what support is available from voluntary (or statutory) services. Gaps in provision (e.g., restricted access for certain population groups) coupled with increasingly long waiting times and capped numbers of sessions for therapeutic support (due to limited staff/capacity/how therapy has been commissioned) further increase victim-survivors’ challenges accessing the right support at the right time | Phase 1: Accessibility and duration of support |

| Phase 2: Referral patterns and pathways; experiences of accessing services | ||

| The ways services are organised and delivered, underpinned by services’ values and philosophies | Services’ philosophies and approaches play a critical role in shaping the nature of support offered and, in turn, the experiences of victim-survivors. These differences between voluntary and statutory services can be overlooked if people do not have specialist knowledge of the field and the history and experience of SV provision within the voluntary sector. Differences include, for example, the degree to which the political, social and economic dimensions of sexual violence are recognised and engaged with vs. more clinically led models of therapeutic support. These differences allow for ‘choice’ of provision for victim-survivors | Phase 1: The uniqueness of specialist services |

| Phase 2: Innovative practices to engage underrepresented groups | ||

| Phase 3: Different approaches to therapy models; different principles underlying service delivery | ||

2.5. Development of a New Model

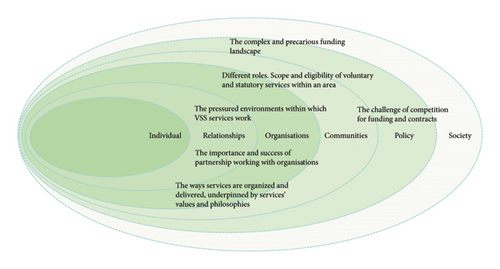

Inspired by Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory [28], we captured the integrated findings conceptually and diagrammatically (Figure 1). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model holds that an individual is influenced by the reciprocal relationships between a person and their environments (and the different ‘systems’ in that environment). Presented as a pattern of concentric rings, the individual exerts influence on and is influenced by the different systems. The model shows the influence of micro- and macrolevel factors associated with SV and how a victim-survivor might operate and interact with the five systems, from proximal to distal.

Figure 1 adapts Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model to map how the organisation and funding of VSS services shape the experience of victim-survivors. The model helps to explain the precarious and at times desperately long journey that some victim-survivors are forced to navigate when seeking specialist support. It also indicates that at a policy level, investment from government could transform aspects of service delivery by providing commissioners with the resource to invest in VSS services. However, other factors—such as the way that decisions are made, partnerships forged and ‘on the ground’ practice developed—also shape the sustainability and quality of services for victim-survivors. Figure 1 is intended to capture the relationship between micro- and macrolevel factors, thus illustrating how crucial the impacts of commissioning can be on individual victim-survivors.

3. Discussion

3.1. Co-Producing the Study Recommendations

- •

What recommendations do we need to make for the commissioning and provision of VSS services at practice and policy levels?

- •

Based on the study findings, how can we strengthen VSS service provision for victim-survivors of SV?

The event was instrumental in developing the recommendations presented in this article. Additionally, postevent, we have had the opportunity to elicit further feedback from colleagues from VSS organisations and we are confident that this co-production process has resulted in the following 14 recommendations that are both usable and relevant. The recommendations are also underpinned by discussions with key stakeholders that took place throughout the study. For example, the study team liaised with the Ministry of Justice during the development of the Victim’s Bill (now the Victims and Prisoners Act 2024) and made a written submission during the development of the Women’s Health Strategy. The recommendations outlined below do not appear in priority order and are numbered for the purpose of reference, rather than hierarchy, and we draw particular attention to their interconnection. These recommendations are intended primarily as an orientating framework for all parties involving in the funding and commissioning of specialist services, including commissioners, grant funders and VSS organisations. There is particular emphasis on recommendations for commissioners working at national and regional levels, across health, criminal justice and social care.

- 1.

A sustainable funding framework for VSS services is required (e.g., a minimum 5-year funding period) with joined-up commissioning (and funding) from all statutory bodies whose services refer into VSS services.

- 2.

Contracts and grants need to cover core service costs (e.g., contribution to employee pensions, sickness pay, rent, overheads and clinical supervision). Additionally, ‘innovation’ focused activities/projects should be funded separately to core funding.

- 3.

VSS providers would benefit from being entrusted with greater autonomy and discretion in how they use allocated funding. VSS services know their local area and population and are the best placed to know where to allocate resource. Similarly, we suggest that commissioners need to have the ability to operate more flexibly as regards the movement of funds to respond to local needs.

- 4.

The study findings show the importance of grants within the funding landscape and how there should not be an exclusive focus on contracting/tendering services. We suggest that funding for grants should be increased substantially.

- 5.

We recommend that commissioners are trained (where they are not already) and supported to develop requisite specialism in the field of sexual and gender-based violence, as is the norm in other areas of specialist and clinical commissioning. This is crucial for the strategic and decision-making aspects of their role. Similarly, senior VSS practitioners need support and ‘upskilling’ to manage roles relating to grant funding and engaging with commissioners (e.g., training workshops and mentor relationships).

- 6.

There needs to be a closer relationship between commissioners and the services they fund to ensure a greater understanding of the realities, complexities and needs of service provision. This could involve the time spent shadowing within the VSS service.

- 7.

Commissioners should support collaborations and de-emphasise competition via the development of local partnerships, through the allocation of funding, space to host meetings and facilitating introductions between key service staff. However, the study has also shown how partnerships work best when bottom-up and can develop without commissioners specifying who the key agency partners should be.

- 8.

Commissioners need to commission services with close consideration of the needs and sustainability of the workforce. This is critical if the workforce is to continue to attract and retain highly skilled workers. Key issues to consider are the impact of short-term contract work, the expectations placed on practitioners managing high workloads, workers’ ongoing training and development needs and support mechanism that foster and maintain staff wellbeing.

- 9.

There is currently a disproportionate burden on commissioners and practitioners regarding reporting and monitoring requirements, which needs to be reduced, e.g., through the use of similar/the same reporting/monitoring templates. What is considered ‘good’ in these key performance indicators must also be contextualised with an understanding of SV ‘recovery’.

- 10.

Because of their diverse experiences and situations, victim-survivors need ‘choice’ and different options at different timepoints. There needs to be recognition of the value of a range of VSS services—peer support, therapeutic counselling, advocacy, etc.—and resistance to promoting/commissioning overly medicalised models of support. The current focus on short-term counselling often fails to meet need and can overshadow other linked types of support (e.g., creative or systemic therapeutic work and political engagement).

- 11.

Sustainable, long-term design and organisation of services could help eradicate the current hierarchies or ‘tiers’ that can exist within the VSS support system (i.e., referral pathways restricted by funding/criteria controls). This would mean that services can be accessed irrespective of how victim-survivors report/or to whom, how recent their experience of SV or based on demographic characteristics.

- 12.

Training of front-line health professionals (e.g., GPs, health visitors) is important as they are often the first entry/disclosure point to services, as is making it possible for health professionals to refer and signpost victim-survivors into specialist SV services. There is an opportunity to consider learning from pilot and/or localised schemes that are currently in operation in some areas of England.

- 13.

Recognition of the unique value of VSS services is currently patchy, and the expertise of practitioners and senior leaders is not consistently understood among all commissioners and/or statutory services. A cultural change is required, with a shifting of the recognition of what expertise ‘looks like’ when it comes to the provision of practical, therapeutic and social support for victim-survivors of SV.

- 14.

Victim-survivors need to be authentically involved in the decision-making around and development of SV services/provision. This should include involvement at various stages of the commissioning cycle. It should also include involvement at the points at which VSS services conceptualise/develop SV service provision.

3.2. Contextualising the Findings and Recommendations Within a Broader, Health and Social Care Context

This study provides important new empirical evidence from a national perspective about the complexity and precariousness within the VSS sector, with short-term funding from state and independent bodies generating considerable instability for services. It also found examples of the positive difference the longer-term, co-produced funding and commissioning arrangements could make. Concern over existing practice has changed the range and type of support available to victim-survivors of SV. As described by Robinson and Hudson [16], there has been the introduction and expansion of SARCs to provide a range of immediate, short- and longer-term support and assistance to victim-survivors of SV. Over the same period, however, there has not been a similar development and support of VSS services, prompting concern about service quality, as well as long-term sustainability of the sector. As others have highlighted, such precariousness negatively affects staff morale and retention and can undermine sector leaders’ ability to work in a strategic and creative way [31]. It also creates instability for victim-survivors around the longevity of the services they need and use.

The study findings have shown the considerable challenges of competition for funding across the sector, balanced with insights into positive models of partnership working. Our findings regarding the problems of short-term funding have been acknowledged previously as an undermining factor for organisational stability, particularly in respect of staffing [30]. Evidence indicates that size matters. Large organisations may be better equipped to leverage funding [30], whereas smaller VSS organisations have fewer resources to dedicate to the tendering process. Robinson, Hudson and Brookman [8] report how one of their SV practitioner interviewees commented that ‘agencies subsume their mutual hatred in a desire to secure funding’ (p.419). While they acknowledge that the situation is not quite so bad as to instil hate between multiagency SV partners, they do acknowledge that services are frequently ‘scrabbling around’ for small pots of money. Resonating with our study findings, we found considerable challenge and competition in terms of funding, but far from ‘hatred’, a significant respect between organisations in the sector, who ultimately share the same goal of supporting victim-survivors of SV.

Our study evidences the pressured environment in which practitioners operate across the VSS sector, associated with ‘complexity’ in the lives of those they support and the increase in service demand. Similarly, interviewees in the study by Hester and Lilley [5] described the specialist Independent Sexual Violence Adviser (ISVA) role as one that is varied and complex. More recently, Horvath and colleagues [32] reported that the ISVAs and ISVA managers who completed their survey were experiencing some psychological distress and moderate-to-high vicarious trauma. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the study showed how ISVAs holding high caseloads experienced more psychological distress than ISVAs with lower caseloads. Additionally, the longer the ISVA spent working with clients who have been subjected to SV, the more likely they are to experience vicarious trauma. Like those from our study, these findings show the human cost of pressured VSS environments.

Victim-survivors are, in turn, impacted by these pressured service delivery environments. Echoing wider findings, in our study, we heard consistent testimony from victim-survivors about the challenges of finding the right support and, moreover, accessing this support at the right time for them. This can have a particularly detrimental impact on victim-survivors who have ‘complex’ needs [31]. However, according to Robinson and Hudson [16], some of this can be mitigated through harnessing the advantage of being a VSS organisation, where independence and flexibility are perceived as a strength for gaining access to victim-survivors and maintaining their engagement/confidence.

The study has provided clear evidence of the value that victim-survivors place on VSS services. This is a finding that we had expected, and it is one that has been highlighted by others in earlier research, for example, Maine [33]. It is a finding that needs to be reinforced, however, given the challenges that the sector continues to face in providing sustainable, specialist provision to all victim-survivors. VSS services are seen to provide a space where victims can tell their story without the fear of judgement [16]. They often provide the only ‘safe space’ where disclosure and support tend to be consistently positive and where victim-survivors are ‘held’ in that space [5]. Like earlier research that has shown the value of survivor-centred, trauma-informed approaches [34, 35], our study has highlighted the importance of SV support being needs-led, feminist and trauma-informed, encompassing survivor empowerment and gender awareness.

The important role played by VSS organisations in helping victim-survivors overcome the trauma of SV, and in getting SV recognised as a significant social problem, cannot be overstated [35]. Trauma-informed support involves identifying survivors’ strengths, prioritising their autonomy and considering how identity and context influence their experiences and needs [36]. Becoming a trauma-informed organisation requires organisations to move away from traditional models of support and to re-evaluate their practices and policies so that they operate through a trauma-focused lens [37].

Pemberton and Loeb [31] argue that given that SV impacts women at disproportionate rates compared to men and that SV results from power inequities, the healing journey for survivors must take such issues into account. Feminist therapy specifically acknowledges the mental health risks associated with living in a patriarchal and hegemonic environment [32] for women and men. It espouses feminist values that are premised on the idea of believing women and respecting their confidentiality and autonomy [8]. The study has also shown the importance of survivor empowerment and gender awareness within VSS service delivery. Kulkarni [35] talks of intersectional trauma-informed services, which aligns well with our study findings. Intersectional approaches underscore the ways in which social categories, such as race, class, ability, gender and sexuality, interact to shape victim-survivor experiences and how individuals frequently contend with multiple oppressions [34]. It is this complexity in the lives of many victims-survivors of SV that mirrors the complexity of the commissioning landscape.

3.3. Study Limitations

Conceptually, we grappled with how best to define and operationalise the concept of specialist services for victim-survivors of SV, cognisant of the different ways that services can provide valuable care and support to victim-survivors. We sought to differentiate between services who can and do support victim-survivors but who do not ‘specialise’ in SV, i.e., staff do not receive bespoke training or are required to have specific knowledge, and/or services are not designed primarily or exclusively with the needs of SV victim-survivors in mind. As the aim of the study was to identify, map and explore support for victim-survivors of SV specifically, we judged that this distinction was important to uphold for reasons of conceptual clarity. However, an unintended result of this definition was that it may have excluded the contribution of services with multiple specialisms and/or services that victim-survivors from specific groups are more likely to turn to [38]. This exclusion seems most apparent in terms of not including minoritised women’s services who did not state that they prioritised specialist support around SV but whom regardless would have been accessed by minoritised victim-survivors. This also applies to other specialist services supporting victim-survivors who are minoritised by virtue of their disability and/or sexuality.

Despite these limitations, there were some mitigating factors regarding equality and diversity among study participants. For example, women are disproportionately represented among victim-survivors of SV, and this is reflected in our samples. However, one of our case study sites offered VSS services specifically for men. As a result, the study findings hold insights from the perspectives of male victim-survivors and services, which are likely to have been missing otherwise. Further, as the demographic table indicates, the proportion of victim-survivor participants who identified as being a disabled person was far greater than the proportion of practitioner/commissioner participants. We interpret this as a reflection of the well-documented association between experiences of violence and abuse and poor physical and mental health.

4. Conclusions

Building on existing research, frequently carried out by and for the voluntary sector, the study provides rigorous, original academic evidence around the range, scope, funding and commissioning of VSS services and their unique contribution in the support journeys of victim-survivors. In this article, we have put forward our recommendations that are grounded in the empirical data and have been co-produced with key commissioners and stakeholders in the VSS sector. Our key themes relate to areas for action. As our data imply, the lack of adoption of these recommendations runs the very real risk of losing the specialism, difference and lifesaving work that VSS services contribute. It would also sustain the current status quo (which will become further entrenched) in terms of unequal access to services for victim-survivors, a lack of choice in provision, missed opportunities to build on examples of effective practice, failure to foster improved relationships and ways of working and a failure to ease the debilitating pressures of high-intensity work environments. A systemic change is required whereby (and as our adapted model indicates), in the first instance, government ensures that the VSS sector is adequately resourced and precarity is eliminated. While we acknowledge the constraint of limited budgets, this cannot be the excuse given for failing to provide victim-survivors with the essential services they require.

Disclosure

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study/project was funded by the NIHR Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme (18/02/27).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The study has been registered as ‘sensitive’ by the funder, but anonymised data will be considered for sharing on reasonable request to the study lead.