Dynamics of Unmet Social Care Needs and Depressive Symptoms Among Older Adults: Evidence From a Prospective Study in England

Abstract

This study examines the dynamics of unmet social care needs and the impact on depressive symptoms in a longitudinal study of older people in England. Using data from Waves 8 and 9 of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, we explore the relationship between trajectories of unmet needs amongst disabled or frail older adults aged 65 and over and depressive symptoms, taking into account changes in care needs across time and loneliness. Nested regression models are used to explore the independent impact of trajectories of unmet needs upon depressive symptoms. We find a significant difference in the prevalence of depressive symptoms between those older adults reporting difficulties in performing activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living and those who do not, with these differences outweighing those between older adults with met or unmet care needs. Receiving timely care helps to reduce further overall care needs and, in turn, alleviates depressive symptoms. In contrast, delays or repeat lack of care can increase future social care needs, worsening depressive symptoms. Moreover, loneliness moderates the association between the dynamic pattern of unmet social care needs and depression, while it amplifies one’s depression risk when care is delayed or repeatedly absent. Our results highlight that timely access to social care services alongside interventions to reduce loneliness could play a role in supporting mental health in later life.

1. Introduction

Ensuring access to services to support older people maintain their functional ability, including activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADL (IADL), is crucial for healthy ageing worldwide [1, 2]. Meeting older adult’s social care needs is vital for helping them cope with daily challenges and preserve their health, well-being and dignity [3]. However, prior research has demonstrated that high levels of unmet social care need persist in both developed and developing countries [4–6]. In England alone, an estimated 1.6 million people aged 65 and over have unmet care and support needs, with hundreds of thousands who report difficulty in performing three or more ADLs being without adequate assistance; a significant proportion of older adults either lack any assistance with basic tasks such as getting out of bed, using the toilet and eating or receive insufficient support [7]. Those reporting unmet social care needs utilize healthcare services more frequently [8–10] and have a higher mortality rate [11].

Older people can face mental health issues just like anyone else, with depression being the most common difficulty. In England, depression has been estimated to affect between 9% [12] to 22% [13] of people aged 65 or older living in communities, with the prevalence being even higher among older people in care homes at around 40% [14]. Depression has been found to be associated with functional disability, suffering from comorbidity of a range of medical disorders and social deprivation [12]. There has, however, been little attention paid to the role that experiencing an unmet need for social care may play.

Whilst there is no consensus on defining and measuring “needs” and “unmet needs” for social care, a commonly adopted approach involves assessing an individual’s ability to independently perform a range of ADLs and IADLs and then establishing whether, or not, the older person receives assistance with these tasks. For those who are not able to perform an activity independently, lack of assistance then denotes an unmet social care need [4]. Social care needs and the associated support received (or not) can fluctuate over time, influenced by changes in an individual’s circumstances that may impact upon their demand (or need) for care and by the supply of social support from family, neighbours and friends or formal services. Some older adults may receive the help they need promptly and adequately, but others may experience care needs that are met but only after some time, that is ‘delayed needs met’, or that are repeatedly or persistently unmet [15].

Existing research has highlighted the relationship between social care needs and mental well-being. According to the activity restriction model proposed by Williamson and Christie [16], when older individuals face physical disabilities or health conditions that limit their ability to engage in valued daily activities, this can lead to the emergence of mental illness. Difficulty with performing ADLs can serve as a significant psychological stressor due to the loss of independence and self-care abilities. This loss often leads to decreased energy, motivation and social interaction, contributing to the development of depressive symptoms. Research indicates that individuals facing challenges in performing basic ADLs, such as dressing, bathing and using the toilet, are more prone to experiencing depressive symptoms [17, 18]. Moreover, individuals requiring assistance with ADL tasks and experiencing more significant ADL difficulties tend to report higher levels of depressive symptoms [19]. In cases of greater disability, despite efforts such as environmental adaptations, mobility aids and caregiving, some needs may remain unmet [20].

Long-term care services are designed to alleviate the constraints imposed by disability, thereby reducing the burden on older individuals [21]. Without adequate long-term care, disabled older adults are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of disability, heightening the risk of detrimental impacts on their mental well-being. Prior research indicates that older adults facing challenges in meeting their needs who do not receive adequate support are more prone to experiencing negative consequences, spanning physical, functional and emotional domains. LaPlante et al. [22] found that individuals living alone and experiencing unmet needs face more adverse outcomes compared to those living with others. These consequences include discomfort, weight loss, dehydration, falls, burns and dissatisfaction with received assistance. Chong et al. [23] further highlighted that individuals with unmet needs often feel dissatisfied with how they spend their time and perceive less control over their lives. Unmet ADL and IADL needs have also been found to be associated with elevated anxiety symptoms [24]. Choi and McDougall [25] observed a positive correlation between the number of unmet needs and older adults’ depressive symptoms, albeit with this explaining only a small portion of the variance.

In other studies, however, the relationship between unmet care needs and mental health has been found to only exist for certain subgroups or not at all. For instance, Hu and Wang [5] found that unmet needs were related to more severe depressive symptoms among rural Chinese older adults, with unmet need reflecting barriers in accessing care services related to population dispersion, geographic isolation and poor transportation links. Conversely, no significant relationship between unmet need and depression was evident among urban older adults. Most of the existing studies have relied upon cross-sectional data and analyses. One of the few studies that used longitudinal data found no association between unmet social needs and mental well-being. Dunatchik et al. [26] concluded that changes in well-being over a 10-year period were primarily influenced by factors such as ageing, financial circumstances and changes in the extent of care needs rather than unmet needs per se.

-

H1. We hypothesize that older adults who experience delays in having their needs met or who encounter persistent unmet needs are more likely to experience depressive symptoms compared to those whose needs are promptly addressed.

We postulate that the way older individuals react to unmet needs plays a crucial role in their susceptibility to depression. Drawing from the ‘stress and coping’ theory proposed by Folkman and Lazarus [27], when confronted with disabilities, older individuals differentially adopt coping strategies influenced by their personal attributes and social context. Stress arises when the older person perceives that the demands placed on them outweigh their ability to cope effectively.

-

H2. Loneliness is hypothesized to have an amplification effect.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analytic Sample

This study employs data from Waves 8 and 9 of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). These waves were collected between May 2016 and June 2017 and June 2018 and July 2019, respectively. The data predate COVID-19 and thus are unaffected by the changes in social contact experienced by many older people during the pandemic, resulting from the need to isolate socially. The ELSA, initiated in 2002, gathers information on the physical and mental health, as well as demographic and socio-economic circumstances, of a representative sample of individuals aged 50 and over living in the community [33].

The analysis here focusses on ELSA panel respondents aged 65 and above who participated in both Waves 8 and 9. Survey longitudinal weights were applied to all analyses to address potential biases stemming from sample attrition across different survey waves. Appendix Figure 1 illustrates the selection process of the analytical sample through a flowchart. At Wave 8, 2863 older adults reported no ADL or IADL difficulty, and 845 reported at least one ADL or IADL difficulty.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for data collection in Waves 8 and 9 of the ELSA was obtained from the South Central—Berkshire Research Ethics Committee (15/SC/0526; 17/SC/0588), with informed consent acquired from all participants, ensuring anonymisation of all observations. As this study relied on secondary data analysis, no further specific approval was required.

2.3. Measurements

Depressive symptoms: The widely recognized eight-item version of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [34] is used to assess depressive symptoms. This self-report instrument aids in identifying individuals at risk of depression in population-based studies. The questionnaire covers feelings of sadness and physical complaints such as restless sleep over the past week. Respondents indicate their response to each item as “yes” or “no,” resulting in a total score ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 8 (all eight symptoms), with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. This abbreviated version has demonstrated strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.90) and performs comparably to the full 20-item CES-D [35]. Additionally, the CES-D provides cutoff scores to identify individuals at risk of clinical depression. A total CES-D score of 3 or higher indicates ‘caseness,’ a definition validated against standard psychiatric interviews in older populations [36]. Depressive symptom scores and caseness were measured at Wave 8 as baseline measurements and at Wave 9 as outcome measurements.

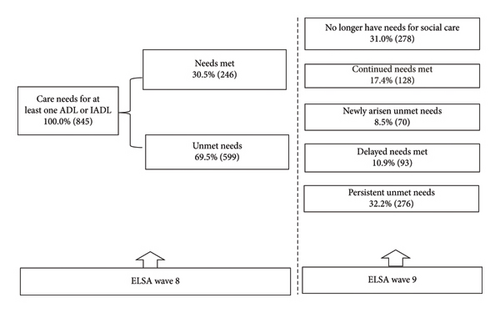

Dynamics of social care needs: In this study, individuals are categorized as having ‘unmet social care needs’ at each wave if they reported difficulties in ADLs (dressing, walking across a room, bathing or showing, eating, getting in and out of bed and using the toilet) or IADLs (shopping for groceries, taking medications, doing work around the house and garden and managing money) without receiving help for at least one of the ADL/IADL difficulties. Some older adults received assistance at Wave 8. Among these individuals, the majority continued to receive support that adequately met their needs at Wave 9, defined as ‘continued needs met.’ Additionally, some reported no longer experiencing difficulties (‘no longer have needs’), while a small subset experienced newly arisen unmet needs due to a lack of assistance at Wave 9. Conversely, some older adults had unmet needs at Wave 8. Among this group, some received assistance meeting their needs at Wave 9 (‘delayed needs met’), while others continued to lack support (‘persistent unmet needs’). Hence, the dynamics of social care needs over the observation period are categorized into five groups: ‘no longer have needs’, ‘continued needs met’, ‘delayed needs met’, ‘newly arisen unmet needs’, and ‘persistent unmet needs’. This classification has been used in previous studies [15].

Loneliness and changes in loneliness across two Waves: At Wave 8 and Wave 9, respondents were asked about the frequency of their loneliness experiences over the past 4 weeks. They were provided with three response options: (a) hardly ever or never, (b) some of the time, and (c) often. Given the low incidence of respondents reporting feeling lonely often, we combined the latter two categories into a single group. Thus, the responses are categorized as ‘Hardly ever or never’ versus ‘Some of the time or often.’ Baseline loneliness was measured at Wave 8. Changes in loneliness across two Waves were classified into two groups based on the changes in the frequency of feeling lonely (‘worsening’ if respondents became more frequently feeling lonely in Wave 9 than in Wave 8, ‘no change or improved’ otherwise).

Other covariates are considered potential confounders in the relationships between the dynamics of unmet social care needs and depressive symptoms, referring to the behavioural model and access to care [37]. Information regarding a range of predisposing, enabling and need characteristics was collected during the survey. ‘Predisposing factors’ included here include age, gender, marital status (married/civil partnered and divorced/separated/widowed/single never married), household wealth quintile and living arrangements (alone and with spouse or not alone). ‘Need’ characteristics are represented by the number of ADL and IADL difficulties (1 and more than 1), baseline depressive symptoms and the number of chronic conditions. The baseline of covariates at Wave 8 and their changes across Wave 8 and Wave 9 were also assessed.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The first stage of the analysis compares the weighted prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults with no ADL or IADL difficulties, those with any difficulties but met their care needs and those with difficulties but unmet their care needs at Wave 8. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests with post hoc tests are applied for pair comparison of the mean depressive symptom score. Chi-square tests with post hoc tests are applied for paired comparison of depression caseness. The weighted percentages of each trajectory of the unmet social care needs dynamics across Wave 8 and Wave 9 are then calculated (Figure 1). Weighted bivariate analyses are then used to examine depressive symptom patterns. For continuous variables, one-way ANOVA is used, whilst Chi-square tests are employed for categorical variables (Table 1).

| Mean sum score of depressive symptoms (Wave 9) | Depression caseness (%) (Wave 9) | Number of respondents (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2.27 | 36.0 | 845 (100.0) |

| Dynamics of social care needs from Wave 8 to Wave 9 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| No longer have needs for social care | 1.57 | 22.5 | 278 (31.0) |

| Continued needs met | 2.29 | 36.5 | 128 (17.4) |

| Newly arisen unmet needs | 2.16 | 34.6 | 70 (8.5) |

| Delayed needs met | 3.01 | 47.5 | 93 (10.9) |

| Persistent unmet needs | 2.70 | 45.2 | 276 (32.2) |

| Age | p = 0.970 | p = 0.926 | |

| 65–74 | 2.25 | 36.7 | 319 (37.9) |

| 75–84 | 2.27 | 35.6 | 337 (33.9) |

| 85+ | 2.29 | 35.3 | 189 (28.2) |

| Gender | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Male | 1.84 | 27.5 | 322 (39.7) |

| Female | 2.55 | 41.6 | 523 (60.3) |

| Marital status | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Married/civil partnered | 1.88 | 28.2 | 466 (54.2) |

| Divorced/separated/widowed/single never married | 2.73 | 45.2 | 379 (45.8) |

| Marital status changes across two waves | p = 0.312 | p = 0.262 | |

| No change or became married/civil partnered | 2.26 | 35.7 | 826 (97.8) |

| Became divorced/separated/widowed/single never married | 2.74 | 47.6 | 19 (2.2) |

| Wealth quintile | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Lowest | 2.90 | 50.0 | 189 (25.5) |

| 2nd | 2.44 | 39.9 | 198 (24.9) |

| 3rd | 2.18 | 33.3 | 190 (21.3) |

| 4th | 1.73 | 24.3 | 147 (16.2) |

| Highest | 1.47 | 19.1 | 121 (12.1) |

| Changes in wealth quintile | p = 0.32 | p = 0.272 | |

| No change or richer | 2.29 | 36.6 | 738 (88.1) |

| Poorer | 2.08 | 31.2 | 107 (11.9) |

| Number of chronic conditions | p < 0.001 | p = 0.017 | |

| 0 | 1.98 | 31.9 | 361 (42.2) |

| 1 | 2.40 | 37.8 | 444 (52.5) |

| 2 and more | 3.18 | 51.0 | 40 (5.4) |

| Changes in the number of chronic conditions | p = 0.676 | p = 0.548 | |

| No change or improved | 2.26 | 35.8 | 801 (94.5) |

| Worsening | 2.39 | 40.0 | 44 (5.5) |

| Loneliness | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Hardly ever | 1.62 | 23.7 | 525 (60.9) |

| Some time or often | 3.28 | 54.9 | 320 (39.1) |

| Changes in loneliness | p = 0.038 | p = 0.004 | |

| No change or improved | 2.22 | 34.5 | 767 (89.9) |

| Worsening | 2.70 | 49.5 | 78 (10.1) |

| Living arrangements | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| Live with spouse or others | 2.02 | 31.0 | 539 (63.6) |

| Live alone | 2.70 | 44.6 | 306 (36.4) |

| Changes in living arrangements | p = 0.080 | p = 0.031 | |

| No changes or became coresidence | 2.25 | 35.4 | 822 (97.0) |

| Became living alone | 2.97 | 55.6 | 23 (3.0) |

| Number of ADL and IADL | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| 1 | 1.93 | 28.4 | 373 (42.4) |

| 2 and above | 2.52 | 41.4 | 472 (57.6) |

| Changes in the number of ADL and IADL | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |

| No change or improved | 1.93 | 29.9 | 588 (68.5) |

| Worsening | 2.99 | 49.1 | 257 (31.5) |

- Note: Data source: ELSA Wave 8 and Wave 9. The p values for the mean score of depressive symptoms are from the ANOVA tests; the p values for depression caseness (%) are from the Chi-square tests. Longitudinal weights are applied.

The second stage of the analysis employs a series of nested regression models to investigate the independent impact of the dynamics of unmet care needs on depressive symptoms (Table 2). In order to examine how the estimated effects of the key independent variable change once other variables are controlled for, Model 1 solely includes the dynamic of social care to describe the unadjusted effect. Model 2 introduces additional variables including the Wave 8 age, gender, marital status, wealth quintile, chronic conditions, loneliness, living arrangements, changes in these covariates over time and the Wave 8 sum score of depressive symptoms. Model 3 further incorporates the Wave 8 number of ADL and IADL difficulties and changes across two Waves. Lastly, to assess the moderating effect of loneliness, Model 4 incorporates an interaction term between the dynamic of social care needs and loneliness. Results are weighted with longitudinal weights using svy commands in STATA SE 18 [38] and presented as regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals.

Sum score of depressive symptoms (Wave 9) Coefficients (β) (95% confidence interval) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Dynamics of social care needs from Wave 8 to Wave 9 | ||||

| No longer have needs for social care (ref) | ||||

| Continued needs met | 0.72∗∗ (0.30–1.13) | 0.43∗ (0.07–0.79) | 0.05 (−0.32–0.43) | 0.01 (−0.39–0.41) |

| Newly arisen unmet needs | 0.59∗ (0.11–1.07) | 0.54∗ (0.12–0.97) | 0.14 (−0.30–0.59) | −0.16 (−0.63–0.31) |

| Delayed needs met | 1.44∗∗∗ (0.82–1.06) | 0.65∗∗ (0.21–1.14) | 0.30 (−0.12–0.73) | −0.12 (−0.54–0.31) |

| Persistent unmet needs | 1.13∗∗∗ (0.72–1.53) | 0.48∗∗∗ (0.18–0.75) | 0.16 (−0.14–0.46) | −0.10 (−0.44–0.25) |

| Age | ||||

| 65–74 (ref) | ||||

| 75–84 | 0.18 (−0.08–0.44) | 0.11 (−0.15–0.36) | 0.11 (−0.14–0.36) | |

| 85+ | −0.05 (−0.36–0.27) | −0.20 (−0.51–0.11) | −0.20 (−0.51–0.11) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (ref) | ||||

| Female | 0.19 (0.05–0.44) | 0.21+ (−0.03–0.45) | 0.23+ (−0.01–0.47) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/civil partnered (ref) | ||||

| Divorced/separated/widowed/single never married | 0.25 (−0.19–0.69) | 0.30 (−1.22–0.96) | 0.30 (−0.11–0.71) | |

| Marital status changes across two waves | ||||

| No change (ref) | ||||

| Became divorced/separated/widowed/single never married | −0.07 (−1.16–1.02) | −0.13 (−1.22–0.96) | −0.16 (−1.27–0.94) | |

| Wealth quintile | ||||

| Lowest (ref) | ||||

| 2nd | −0.27 (−0.62–0.08) | −0.26 (−0.61–0.08) | −0.28 (−0.61–0.06) | |

| 3rd | −0.12 (−0.48–0.23) | −0.06 (−0.40–0.28) | −0.07 (−0.41–0.26) | |

| 4th | −0.33+ (−0.70–0.04) | −0.23 (−0.60–0.14) | −0.24 (−0.61–0.12) | |

| Highest | −0.44∗ (−0.85–0.04) | −0.41∗ (−0.82–0.01) | −0.40∗ (−0.80–0.01) | |

| Changes in wealth quintile | ||||

| No change or richer (ref) | ||||

| Poorer | 0.21 (−0.14–0.55) | 0.17 (−0.17–0.50) | 0.16 (−0.17–0.50) | |

| Number of chronic conditions | ||||

| 0 (ref) | ||||

| 1 | 0.10 (−0.14–0.35) | 0.12 (−0.12–0.35) | 0.13 (−0.11–0.37) | |

| 2 and more | 0.16 (−0.45–0.76) | 0.14 (−0.41–0.65) | 0.10 (−0.41–0.62) | |

| Changes in the number of chronic conditions | ||||

| No change or reduced (ref) | ||||

| Increased | −0.07 (−0.73–0.58) | −0.07 (−0.70–0.57) | −0.09 (−0.72–0.53) | |

| Loneliness | ||||

| Hardly ever (ref) | ||||

| Some time or often | 0.70∗∗∗ (0.40–1.00) | 0.66∗∗∗ (0.37–0.95) | 0.17 (−0.27–0.61) | |

| Changes in loneliness | ||||

| No change or improved (ref) | ||||

| Worsening | 0.89∗∗∗ (0.43–1.36) | 0.88∗∗∗ (0.43–1.33) | 0.87∗∗∗ (0.42–1.32) | |

| Wave 8 sum score of depressive symptoms | 0.52∗∗∗ (0.44–0.60) | 0.52∗∗∗ (0.44–0.60) | 0.52∗∗∗ (0.44–0.60) | |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Live with spouse or others (ref) | ||||

| Live alone | −0.22 (−0.67–0.22) | −0.23 (−0.64–0.18) | −0.21 (−0.63–0.20) | |

| Changes in living arrangements | ||||

| No change or became coresidence (ref) | ||||

| Became living alone | 0.42 (−0.37–1.21) | 0.59 (−0.17–1.36) | 0.58 (−0.19–1.36) | |

| Number of ADL and IADL | ||||

| 0 or 1 (ref) | ||||

| 2 and above | 0.07 (−0.18–0.32) | 0.06 (−0.18–0.30) | ||

| Changes in the number of ADL and IADL | ||||

| No change or reduced (ref) | ||||

| Increased | 0.82∗∗∗ (0.54–1.11) | 0.79∗∗∗ (0.52–1.07) | ||

| Dynamics of social care needs # loneliness | ||||

| Continued met # sometime or often lonely | 0.20 (−0.55–0.95) | |||

| Newly arisen unmet needs # sometime or often lonely | 1.10∗ (0.06–2.14) | |||

| Delayed needs met # sometime or often lonely | 1.03∗ (0.22–1.84) | |||

| Persistent unmet needs # sometime or often lonely | 0.72∗ (0.13–1.31) | |||

| Constant | 1.57∗∗∗ (1.35–1.80) | 0.31 (−0.37–1.21) | 0.26 (−0.12–0.65) | 0.41∗ (0.02–0.80) |

| R square | 0.0605 | 0.4526 | 0.4770 | 0.4854 |

- Note: Data source: ELSA Wave 8 and Wave 9.

- ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001.

- ∗∗p ≤ 0.01.

- ∗p ≤ 0.05.

- +p ≤ 0.1.

2.5. Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses are conducted by repeating the analyses using a binary outcome variable (1 = depression caseness) using multivariate logistic regression models (Appendix Table 1).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

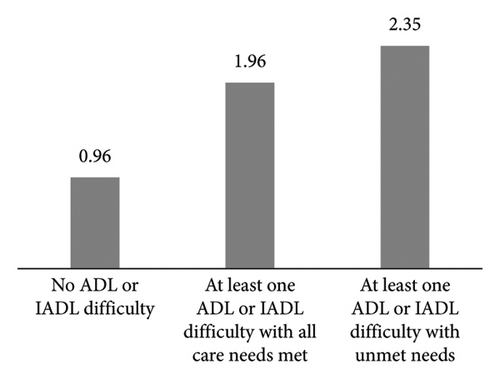

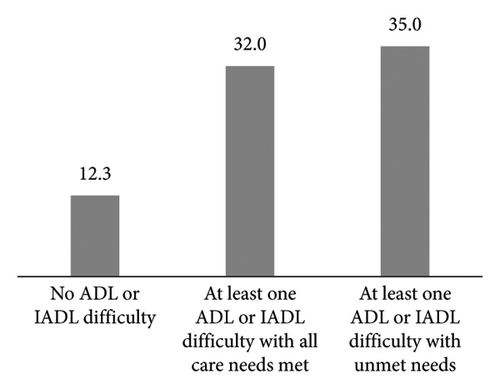

At baseline (Wave 8), the majority of older adults aged 65 and above (74.6%, n = 2863) reported having no ADL or IADL difficulties (Group A), and 7.7% (n = 246) had at least one ADL or IADL difficulty but had all their care needs met (Group B), while 17.7% (n = 599) had at least one ADL or IADL difficulty where their needs for assistance in performing the task were unmet (Group C). The average depressive symptoms among these three subgroups were 0.96, 1.96 and 2.35, respectively. ANOVA tests show that there are significant group differences (p < 0.001). The post hoc tests show that the mean depressive symptoms among Group A are lower than Group B (p < 0.001) and Group C (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the mean depressive symptoms among Group B are lower than Group C (p = 0.004). The prevalence of depression caseness among these three subgroups was 12.3%, 32.0% and 35.0%, respectively. This prevalence among Group A is lower than Group B (p < 0.001) and Group C (p < 0.001), and the prevalence among Group B is lower than Group C (p = 0.044) (Figure 2). These results indicate that the disparity in depressive symptoms between older adults with or without ADL or IADL difficulties is much greater than that between those with met or unmet care needs.

The remainder of the analyses are conducted among 845 older adults aged 65 and above who reported at least one ADL or IADL difficulty at Wave 8 (i.e., Groups B and C). At Wave 9, the mean age was 78.5 (SD = 7.7), and 60.3% were women.

At Wave 8, amongst all older adults who reported at least one ADL or IADL difficulty, 30.5% had all their care needs met, while 69.5% had at least one unmet care need. By Wave 9, 31.0% of older adults no longer required social care (i.e., no longer reported any ADL or IADL difficulty), 17.4% had continued needs met, 8.5% had newly arisen unmet needs, 10.9% had delayed needs met, and 32.2% had persistent unmet needs (Figure 1). Older adults who no longer need social care tend to be younger, male, have only one ADL or IADL difficulty or come from more affluent households.

Table 1 displays bivariate associations between the dynamics of social care needs and depressive symptoms at Wave 9. The mean sum score of depressive symptoms at Wave 9 is 2.27, with 36.0 of respondents classified as experiencing depression caseness. Significant associations are observed between the dynamics of social care needs and depressive symptoms. Respondents with delayed needs met or persistent unmet needs exhibit higher mean sum scores of depressive symptoms (3.01 and 2.70, respectively) or a greater proportion of depression caseness (47.5% and 45.2%, respectively). Conversely, respondents who received prompt care which met their needs at Wave 8 and no longer required social care at Wave 9 have the lowest sum score (1.57) or the lowest proportion (22.5%) of depression caseness.

Additionally, women, respondents from lower-income households, those living alone, individuals reporting loneliness and those with two or more chronic conditions or ADL and IADL difficulties at Wave 8 show higher sum scores of depressive symptoms or a greater proportion of depression caseness. Over time, those with worsening chronic conditions, loneliness or a higher number of ADL and IADL difficulties had a poorer outcome compared to those without such changes.

3.2. Multivariate Analysis

Table 2 presents the results of multivariate analyses. Model 1 includes a single variable showing the dynamics of social care. At Wave 9 (Model 1), respondents who still had needs, either met or unmet, had a higher sum score of depressive symptoms compared to those who no longer had any needs.

Model 2 incorporates additional demographic, socioeconomic and health variables. The association between the dynamics of unmet social care needs and the sum score of depressive symptoms remains. Older adults who reported loneliness or were more depressed at baseline reported a higher score of depressive symptoms, while those in the highest wealth quintile had a lower score. The results reflect that the differences in depression among respondents with unmet need changes were partly due to the fact that they also differ on other important variables, such as wealth, loneliness and the score of depressive symptoms at baseline.

Model 3 then further includes the total number of ADL and IADL difficulties at baseline and changes over time. Now, coefficients of the dynamics of unmet social care needs are not significantly different to those who no longer have any needs at Wave 9, suggesting that the remaining differences in depression among respondents with unmet need changes were due to the changes in the number of ADL and IADL difficulties across Wave 8 and Wave 9.

Finally, Model 4 introduces an interaction term between the dynamic of social care needs and loneliness. Respondents experiencing newly arisen unmet needs, delayed needs met, or persistent unmet needs and feeling lonely sometimes or often exhibit a higher sum score of depressive symptoms (Model 4). The results indicate that loneliness moderates the association between the dynamic pattern of unmet social care needs and depression. Perceived loneliness amplifies the depression risk for respondents with care needs delayed met or unmet persistently.

3.3. Sensitivity Analyses

The sensitivity analyses show similar results (Appendix Table 1). At Wave 9 (Model 1), respondents with ongoing needs (met or unmet) were more likely to be depressed than those with no needs. Model 2 added demographic, socioeconomic and health variables. The link between unmet social care need dynamics and depression persisted. Model 3 included baseline ADL and IADL difficulties and their changes. Odds ratios for unmet social care need dynamics were not significantly different from those with no needs at Wave 9. Finally, Model 4 added an interaction term for social care need dynamics and loneliness. Loneliness moderates the relationship between unmet social care need dynamics and amplifies depression risk for those with persistent unmet needs. Compared to the main results, loneliness does not moderate the association between experiencing newly arisen unmet needs and depression, nor does it moderate the association between experiencing delayed-met needs and depression. This might be because the sum score of depressive symptoms as a continuous variable often has more statistical power to detect differences and relationships than a binary variable of depression caseness.

4. Discussion

The results presented above highlight that amongst older people living in the community, those adults with unmet care needs experience a higher level of depressive symptoms than those whose care needs met. However, the significant difference in depressive symptoms between older adults with and without ADL or IADL difficulties outweighs the differences between those with met or unmet care needs when looked at cross-sectionally. The levels of depressive symptoms found in our study align with prior research findings [12–14].

Importantly, our analysis also provides new insights into the changes in care needs and social care provision over 2 years. At baseline, nearly one-third of the participants had their social care needs fully addressed. However, the majority of older adults who reported being unable to perform ADLs independently experienced some level of unmet care needs (69.5%), highlighting gaps in the provision of social care services. Over the observation period of 2 years, a notable proportion of older adults who previously had a need (31.0%) no longer required social care, suggesting potential improvements in their health status or support systems. Some older adults (17.4%) continued to have their care needs met, indicating ongoing support and stability in their care arrangements. This can also be due to a transformation in care arrangements that dynamically adapt to changes in social care needs. A small percentage of older adults (8.5%) developed new care needs that were not addressed, highlighting emerging challenges or changes in their circumstances. Just over one in 10 older adults experienced delayed care provision (10.9%); these respondents may have faced barriers or delays in accessing social care services, potentially impacting their well-being. Concerningly, nearly one in three of those in need (32.2%) experienced persistent unmet care needs over time, indicating ongoing challenges or deficiencies in the social care system. These results were consistent with the previous study [15] which focussed only on unmet bathing and dressing performance needs. They underscored the dynamic nature of social care needs among older adults and the variability in care provision over time. While some individuals experienced improvements or no longer required social care, a considerable proportion of older adults faced ongoing or newly arisen unmet needs, highlighting the importance of responsive and flexible care systems that can adapt to changing circumstances and support the diverse needs of older populations.

The descriptive analysis reveals that older adults who faced delays in receiving necessary care or persistent unmet needs reported higher average levels of depressive symptoms or met the criteria for depression. Conversely, older adults who no longer required social care exhibited lower average levels of depressive symptoms and were less likely to meet the criteria for depression. Delays in receiving necessary care or persistent unmet needs can evoke feelings of frustration, helplessness and diminished self-worth among older adults. The inability to access essential care and support may foster feelings of despair and hopelessness, heightening the risk of depressive symptoms [25, 39].

While an association exists between the dynamics of social care needs and depressive symptoms among older adults, this relationship weakens when considering additional factors such as baseline depressive symptoms, loneliness and wealth. Moreover, the association is not statistically significant once the extent of care needs at Wave 8 and changes across the two Waves are taken into account. Thus, hypothesis 1 was only partially supported. The underlying mechanisms linking unmet needs and depression require further investigation and are likely multifaceted, involving several interconnected factors. For instance, older adults facing unmet social care needs may also encounter poor mental health, poverty or social isolation and loneliness, which are recognized risk factors for depression and can exacerbate existing mental health challenges [12, 29]. Relying on others for assistance with daily activities due to unmet care needs can result in a loss of independence and autonomy, negatively affecting older adults’ sense of control and identity. Increasing loss of independence often accompanies feelings of sadness, frustration, and grief, which can further contribute to depressive symptoms [39]. Therefore, receiving timely care helps eliminate future care needs and, in turn, alleviates depressive symptoms. In contrast, delays or repeat lack of care may increase one’s needs further and exacerbate their depressive symptoms.

Our results highlight that there is a complex relationship between social care needs and loneliness, influencing mental health outcomes among older adults, thereby supporting Hypothesis 2. Loneliness has an amplification effect on the relationship between unmet needs and depressive symptoms. The findings suggest that individuals experiencing newly arisen unmet needs, delayed needs met or persistent unmet needs, along with feelings of loneliness, tend to exhibit higher scores of depressive symptoms. The process of how people cope with stress consists of stress assessment and adopting coping strategies. Loneliness impacts this process. Lonely individuals appraise the same stressors, such as unmet social care needs, as more burdensome, leading to frustration and helplessness, thereby exacerbating depressive symptoms [25]. They also tend to use less effective coping methods, such as avoidance or self-blame, when faced with these stressors. It could intensify their sense of distress and elevate the risk of depressive symptoms [30, 40]. This underscores the intertwined nature of unmet social care needs and loneliness in contributing to psychological distress among older adults.

5. Conclusion

This study sheds new light on the relationship between the dynamic aspects of unmet social care needs and their association with depressive symptoms among older adults requiring social care. For some older individuals, the experience of unmet needs in daily activities may be short-lived once they receive timely and adequate care. However, for others, this experience may persist for a significant period if their needs remain unaddressed. Interestingly, the dynamic of unmet social care needs does not exhibit a direct association with depressive symptoms. Instead, its impact appears to be mediated indirectly through ongoing circumstances, such as feelings of loneliness and the extent of care needs. Moreover, the combined effect of loneliness and the dynamic of unmet social care needs strengthens the negative impact on depressive symptoms.

These findings underscore the complex interplay between social care needs, loneliness and mental health outcomes among older adults. There is a clear need for early detection and intervention programs aimed at identifying elderly individuals at risk of developing ADL and IADL difficulties. Implementing screening programs in healthcare settings to identify individuals with unmet needs and providing timely support can help prevent further deterioration of their functional abilities. Policymakers should also advocate for integrated care approaches that address the health and care needs of elderly adults. This could entail collaboration among healthcare providers, social services, and community organizations to deliver comprehensive support tailored to individuals’ needs, addressing the immediate care needs as well as the social and emotional well-being of older individuals to mitigate the risk of depressive symptoms. Interventions aimed at reducing loneliness, improving timely access to social care services and providing comprehensive support tailored to individual needs may help alleviate the negative effects observed in this study. Given the amplification effect of loneliness, we need to consider perceived loneliness during local authority care need assessment processes, care coordination and care delivery. Also, in light of the UK government strategy on tackling loneliness, community infrastructure (e.g., better transport, community spaces and digital platforms) can play a critical role in reducing loneliness, improving well-being and alleviating pressure for the health and social care system.

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

One of this study’s strengths is its nationally representative longitudinal design, which allows it to capture the change in unmet social care needs and depressive symptoms over two points in time. Another lies in its exploration of the dynamic definition of social care needs, which allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between unmet social care needs, loneliness and depressive symptoms.

However, there are some limitations. We acknowledge that disability is socially constructed rather than an individual intrinsic condition. Given the data restriction, we placed more emphasis on individual-level constraints; however, this does not mean that individuals’ social environments have no role in shaping individuals’ experience of disability. Future research should address this by examining the role of societal barriers in shaping the experiences of disabled individuals. The observational nature of the study limits the ability to establish causality between social care needs and depressive symptoms. While associations can be identified, causative relationships cannot be definitively determined without experimental research designs that account for selection. The dynamics of unmet social care needs in Model 3 are not statistically significant. This result might be attributable to a small sample size. Combining data from multiple waves will boost the sample size and help with statistical inferences. While the study utilizes a nationally representative sample, the findings may not be fully generalizable to older adults in other countries or cultural contexts, particularly those with different social care systems or cultural norms regarding ageing and caregiving. These results only apply to those outside institutionalized care facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council Centre for Population Change-Connecting Generations Centre (grant number: ES/W002116/1).

Supporting Information

Appendix Figure 1: Analytic sample selection procedure.

Appendix Table 1: Multivariate analyses (logistic regression).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used for this study are available from the UK Data Service on request.