Effects of Fear of Crime on Social Acceptance Under Social Conflict Perceptions Toward Ex-Prisoners: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

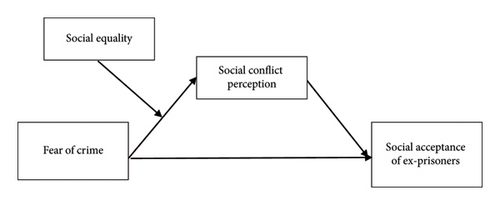

Fear of crime (FOC) decreases a person’s social acceptance of ex-prisoners (SAX). However, the extent to which FOC impacts SAX is unclear. Using a national sample, this study aimed to explore the extent to which (1) FOC impacts SAX by elevating social conflict perception and (2) social equality moderates the association between FOC and social conflict perception. Using bootstrapping, a moderated mediation effect model was constructed to analyze the extent to which FOC impacts SAX and the potential mediating and possible moderating effects of social conflict perception and social equality, respectively. The findings reveal that FOC significantly and negatively impacts SAX after controlling for sex, age, educational level, marital and subjective socioeconomic statuses, Internet utilization, and victimization experience factors. The results indicate that people with high FOC are less willing to accept ex-prisoners, an effect partly explained by the mediation of social conflict perception, and that social equality plays a moderating role between FOC and social conflict perception. This study contributes to the literature by extending research on the social effects of FOC, as to date, most research has focused on the FOC attitude that favors the punishment of offenders, and there is hardly any research on whether a hostile FOC attitude could spill over toward ex-prisoners in society. In addition, this study explains the association between FOC and the social acceptance of targeted social groups and provides an innovative explanation for a precondition based on the inner relationship between FOC and SAX, supported by empirical evidence.

1. Introduction

Social acceptance can partially satisfy people’s need to belong, and is just as applicable in the process of integrating social groups such as ex-prisoners into society [1]. The need to belong, defined as the desire to form and maintain close and lasting relationships with other individuals [2, 3], has two components. First, people want positive and regular social contact [4, 5]. Second, they desire a stable framework for ongoing relationships in which there is a mutual concern for one another. Nevertheless, fulfilling either of these components (without the opposite person reciprocating) only partially satisfies the need to belong, indicating that kindness and acceptance from others are vital in satisfying the need to belong [4, 6]. Social acceptance plays a multifaceted role [7], improving happiness and quality of life by enabling people’s acceptance in social groups and improving society’s sense of security [5, 8]; further, it reduces the probability of ex-prisoners repeating their deviant behavior or recommitting criminal activities [5, 9, 10]. Scientists in the fields of sociology, criminology, law, and public administration, as well as policymakers, the media, and people in society, must consider the extent to which ex-prisoners can return and reintegrate into society [11, 12]. In fact, ex-prisoners face many difficulties returning to society, including challenges with being accepted by people around them [13].

Current research on ex-prisoners has proven that social acceptance of ex-prisoners (SAX) is relatively low [10], with crime experience being a key factor affecting people’s social acceptance levels [14–16]. However, there is a lack of analysis focused on the conditions or factors affecting ex-prisoners’ social acceptance, such as fear of crime (FOC), an emotional response of dread or anxiety to crime or symbols that a person associates with crime [17]. Furthermore, there is a lack of analytical focus on mechanisms examining the extent of FOC affecting social acceptance of this social group of people and whether any mediation or moderation effects exist.

Therefore, this study is significant as social acceptance increases the confidence of people with special social experiences, such as being formerly incarcerated, especially when those individuals intend to rebuild their social networks. Policymakers, correctional officials, and advocates have increasingly emphasized the importance of enhancing SAX to reduce the psychological burden on ex-prisoners and their families, and protect them from recidivism [13, 18].

This study aims to explore the extent of the impact of FOC on the SAX by elevating the social conflict perception of residents. Furthermore, it examines how social equality moderates the association between FOC and social conflict perception. Lastly, this study tested and confirmed the hypothesis that people with a high FOC are less willing to accept ex-prisoners, an effect that can be partly explained by the mediation of social conflict perception.

The scope of this study is to explore social acceptance and social conflict perception that ex-prisoners might experience in society. The scope of this problem makes it a critical topic because a significant number of prisoners are released annually, after which they are labeled ex-prisoners. Upon returning to the community, they struggle to participate in the labor market because of issues related to social acceptance, which has important implications for their long-term health, family solidarity, and well-being (e.g., [9, 19, 20]). More than 600,000 people are released from prison and return to society every year in the United States [21, 22], while more than 300,000 people released from prison each year in China [23]. Given these numbers, the issue of SAX deserves further attention.

This study used bootstrapping to construct a moderated mediation effect model based on a representative national sample from the Chinese Social Survey (CSS) conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2021. It tested four hypotheses, including exploring whether residents’ FOC affects their SAX, whether social conflict perception plays a mediating role between FOC and SAX, whether social equality moderates the impact of FOC on social conflict perception, and whether social equality moderates the mediating effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception.

This study contributes to the literature, first, by extending research on the social effects of FOC, as, to date, most studies have focused on the FOC attitude, which favors the punishment of offenders. Thus far, scant research has been conducted on whether a hostile FOC attitude could spill over toward ex-prisoners in society. Second, this study proposes a new mechanism, explaining the association between FOC and the social acceptance of targeted social groups, in which people are more likely to have a higher social conflict perception owing to FOC, which may weaken their acceptance level of ex-prisoners. Third, this study provides an innovative explanation for a precondition based on the inner relationship between FOC and social acceptance (through the perception of social conflict); that is, social equality moderates the effect of FOC on people’s social conflict perception toward ex-prisoners. Fourth, this study provides empirical evidence on the impact of social acceptance on the social integration of ex-prisoners.

2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework of this study is based on social acceptance theory. Building on the multidimensional concept of social acceptance theory proposed by Leary [24], successful social acceptance occurs when people signal that they wish to include, accept, and embrace a person in their group and/or relationship, without discrimination or judgment. Further, social acceptance is the process of being included in and respected by others and occurs on a continuum ranging from merely tolerating a person’s presence to actively pursuing someone as a relationship partner [25]. People experience social acceptance in numerous ways [26], such as being chosen for a desirable job or included in the community [13]. Psychologists have devised several innovative methods of manipulating social acceptance, including leading participants to believe that everyone has chosen them to be in their group [16, 27, 28] or having collaborators (real or virtual) include them in a ball-tossing game [29, 30].

Social acceptance theory focuses on the degree to which individuals are accepted, recognized, and respected in groups and society, and the impact of such acceptance on individual mental health and social function. It contends that acceptance is a positive psychological experience that involves psychological interaction between individuals and others/groups, and is the basis for establishing healthy interpersonal relationships and social integration. The theory includes multiple dimensions, such as self-acceptance, peer acceptance, and interpersonal acceptance.

Self-acceptance refers to an individual’s recognition and acceptance of their own characteristics, abilities, and values, which is the prerequisite for forming a positive self-image. It can enhance an individual’s self-esteem and self-confidence, enabling them to better cope with challenges and pressures in life. Peer acceptance refers to the degree to which an individual is accepted and recognized in a peer group, which has an important impact on the social development and emotional health of adolescents. Peer acceptance is affected by many factors, such as an individual’s personality, appearance, ability, and social skills. Interpersonal acceptance, identified as the degree to which an individual is accepted and recognized by others in a wider range of interpersonal relationships (e.g., friends, family, and colleagues), involves the interaction and communication between an individual and others. Good interpersonal acceptance helps individuals establish a stable social network and emotional support system, and enhances their social adaptability.

Based on social acceptance theory, the extent to which people are accepted by society not only affects their social status and reputation but also impacts their sense of social participation and belonging. Social acceptance is critical to ensure that people interact and integrate with society. Accordingly, we argue that the multiple dimensions of social acceptance theory can be used to strengthen the foundation and provide a coherent framework to interpret the issue of social acceptance and social conflict for ex-prisoners. We include self-acceptance and peer acceptance dimensions from social acceptance theory to theoretically explain the perspective of FOC residents regarding ex-prisoners and the extent to which they are able to accept them. We also include interpersonal acceptance from social acceptance theory to explain the extent to which residents create conflict perception and how it impacts their acceptance of ex-prisoners. We have developed our theoretical hypotheses as follows.

-

Hypothesis 1: People with high FOC are less willing to accept ex-prisoners.

Second, people with high FOC are more likely to experience high levels of social conflict perception. Regarding living environment, people with high FOC often live in communities with poor sanitation conditions [39–41], some of which are related to signs of crime, such as graffiti [42, 43]. These communities are relatively chaotic [7], and the cohesion between people in these communities is weak [44], which may cause people with high FOC to directly or indirectly encounter more social conflict while experiencing a high level of social conflict perception [45]. From an individual perspective, FOC causes people to be more sensitive to criminal information and social disorders [17, 46], leading to them easily noticing social conflict in their living environment and heightening their social conflict perception.

-

Hypothesis 2: Social conflict perception plays a mediating role between FOC and SAX.

-

Hypothesis 3: Social equality plays a moderating role in the association between FOC and social conflict perception: When social equality is high, FOC has a smaller impact on social conflict perception; however, when social equality is low, the impact of FOC is larger.

-

Hypothesis 4: Social equality mediates the effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception. In cases where social equality is lower, the mediating effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception is stronger.

3. Method Framework

3.1. Data Source

We used CSS data from 2021, as secondary data, to test the research hypotheses. The CSS is a nationwide sample survey organized by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, which aims to survey factors such as family and social life, work conditions, and social attitudes, among other such variables, of residents in mainland China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). In addition, it aims to provide information for social science research and government on decision-making and social policy implementation by providing scientific survey data. Scholars are encouraged to use CSS data by application (for noncommercial purposes) for academic research through the CSS data website: https://css.cssn.cn/css_sy/. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences used the multistage composed sampling method to collect CSS data in 2021. First, it used population proportionate sampling (PPS) to select 151 counties/cities/districts from 2870 counties in mainland China. Second, it selected 604 village/community committees from 151 counties/cities/districts. Third, it used simple random sampling based on map addresses to select 10,268 households. Fourth, it selected one resident, over 18 years old, from each household to participate in an interview based on simple random sampling.

Face-to-face and computer-assisted interviews (CAPI) were conducted by trained professional investigators under the guidance of supervisors. Respondents provided their informed consent before sharing their responses in the CSS questionnaires. CSS data are highly authoritative and have supported academic research and the publication of hundreds of peer-reviewed papers, books, and consulting reports (e.g., [65, 66]). We employed data from the CSS in 2021 because the data better represent the residents in mainland China and cover several variables of interest in this study, such as FOC, SAX, social conflict perception, and social equality. To the best of our knowledge, other large-scale social surveys with Chinese residents have not included these variables in one survey. Therefore, this study used the CSS conducted in 2021.

The CSS 2021 data officially released by CSS include results for a total of 10,136 residents. During the CSS, residents were randomly selected to answer questions on particular variables, referring to similar academic research outcomes [67]. We removed cases with missing values in core variables such as SAX, FOC, social conflict perception, and perception of social equality. Consequently, we included 3340 residents in our study. The sample consisted of 1806 female participants (54.1%) and 1534 male participants (45.9%). Further analysis revealed that 1999 (59.9%) were rural residents and 1341 (40.1%) were urban residents. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 71 years, with an average age of 44.32 years (standard deviation = 14.44 years).

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. SAX

To determine SAX, the dependent variable of the study, respondents were asked questions such as “How acceptable to you is the idea of ex-prisoners living in your neighborhood?” Participants responded using a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = very unacceptable to 4 = very acceptable). Research has shown that well-designed single items also have high reliability and validity [68], and have therefore been widely used in academic research [69]. Referring to similar academic studies in the literature (e.g., [51]), the responses were used as indicators of SAX, with a higher score indicating a higher degree of SAX.

3.2.2. FOC

Following previous studies, respondents’ fear of damage to property and violence were used to measure their FOC, as the independent variable of the study (e.g., [70, 71]). Specifically, the participants were asked, “How safe do you feel in your current residential neighborhood in terms of (1) personal and family property safety? (2) personal safety?” Participants responded using a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = very unsafe to 4 = very safe). After reverse-scoring the responses, the mean of the two items was used as an indicator of FOC. The higher the score, the stronger the FOC [72]. Cronbach’s α of FOC was 0.806, which is higher than the measurement standard in sociology [73].

3.2.3. Social Conflict Perception

Social conflict perception is the mediator between FOC and SAX. Referring to the academic outcomes of similar studies (e.g., [74]), the responses on the following six items were used as indicators of social conflict perception with questions such as: “Do you think the social conflict between the following social groups is serious?”: (1) the poor and rich, (2) employers and employees, (3) different racial/ethnic groups, (4) different religious groups, (5) locals and outsiders, and (6) officials and ordinary people. Participants responded using a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = no conflict to 4 = very serious). We used the average score of the six items as an indicator of social conflict perception. The higher the score, the higher the social conflict perception. Cronbach’s α of social conflict perception was 0.850.

3.2.4. Social Equality

Referring to the academic outcomes of similar studies (e.g., [67]), the respondents’ answers to the following questions were used as indicators of social equality, as the moderator of this study, including “How equal do you think are the following aspects of current social life?”: (1) college entrance examinations, (2) citizens’ political rights, (3) judiciary and law enforcement, (4) public medical care system, (5) work and employment opportunities, (6) wealth and income distribution, (7) social welfare benefits such as pensions, and (8) differences in social rights and income/benefit between urban and rural areas. Participants responded using a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = very unequal to 4 = very equal). We used the mean value of the eight items as an indicator of social equality. The higher the score, the higher the level of social equality. Cronbach’s α of social equality was 0.869.

3.2.5. Control Variables

To balance the effects of demographic variables, we included these as control variables in our analysis. We controlled for the respondents’ sex (1 = male, 0 = female), age, education level (1 = high school and above, 0 = middle school and below), and marital status (1 = married, 0 = other). Simultaneously, this study measured the household registration of the respondents (1 = rural household registration, 0 = urban household registration), social mobility status (1 = migrant people, 0 = others), and socioeconomic status (SES). This study measured the SES of respondents by asking the question, “What’s your socioeconomic status like compared with people around you in the city you live in?” (1 = high level, 2 = medium to high level, 3 = medium level, 4 = low to medium level, 5 = low level). The respondents’ scores were reverse scored as an indicator of SES; higher scores indicated higher SES. It also measured victimization experience by asking questions such as “Have you or your family members been cheated, stolen from, or robbed in the past 12 months?” (1 = yes, 0 = no) [75] and new media use by asking questions such as “Do you use your smart phone or laptop to search the Internet, for example, to read the news or obtain any information online?” (1 = yes, 0 = no).

3.3. Data Analyses

This study used SPSS and M-plus 8.0 software to analyze the data. First, we conducted a descriptive analysis on variables as residents’ FOC, SAX, social conflict perception, and social equality, including means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients in variables. We then examined the possible risk of common method bias in the research [76]. Second, we tested the four hypotheses based on the methods recommended by experts [64], as follows: (1) testing whether residents’ FOC will affect their response to the acceptance of ex-prisoners (Hypothesis 1); (2) exploring whether social conflict perception plays a mediating role between FOC and acceptance of ex-prisoners (Hypothesis 2); (3) analyzing whether social equality moderates the impact of FOC on social conflict perception (Hypothesis 3); (4) re-analyzing whether social equality mediates the mediating effect of FOC on the acceptance of ex-prisoners through social conflict perception (Hypothesis 4).

The data investigation process by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences is standardized and meets the requirements of scientific research ethics. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Normal University (approval no. AHNU-ET2022073) and has been conducted in accordance with the ethical principles laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Prior to constructing the mediation model, we performed mean-centered processing on the continuous variables [77]. When using bootstrapping to analyze mediation and moderation effects, the number of repeated samplings was set to 10,000. In the following analyses, unless otherwise specified, control variables such as sex, age, and marital status have been added to the model.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis Results

This study presents the correlation between the control variables, including demographic variables, and key variables. In terms of FOC, women, residents with low SES, residents who use the Internet, and residents who have been victimized by crime have higher FOC, which is consistent with research outcomes in the literature [17]. In terms of SAX, young people, residents with high educational levels, urban residents, migrant populations, and residents who use the Internet are more likely to accept ex-prisoners. In terms of social conflict perception, residents who are young, residents with high educational levels, residents who live in cities, migrant residents, residents with low SES, residents who have been victimized by crime, and residents who use the Internet are more likely to believe that there are more conflicts in society. In terms of social equality, young people, people with high educational levels, residents with high SES, and residents who have not been victimized by crime are more likely to think that their society is fair. Table 1 presents significant negative correlations between people’s FOC and SAX, as well as with social conflict perception and social equality. Additionally, the negative correlation between social conflict perception and SAX is significant.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FOC | 1.67 | 0.51 | ||||||||||||

| 2. PSC | 2.45 | 0.60 | 0.24∗∗∗ | |||||||||||

| 3. SAX | 2.06 | 0.61 | −0.06∗∗∗ | −0.10∗∗∗ | ||||||||||

| 4. PSE | 2.92 | 0.53 | −0.33∗∗∗ | −0.33∗∗∗ | 0.11∗∗∗ | |||||||||

| 5. Sex | 0.46 | 0.50 | −0.10∗∗∗ | −0.05∗∗ | 0.02 | −0.02 | ||||||||

| 6. Age | 44.32 | 14.44 | −0.05∗∗ | −0.16∗∗∗ | −0.24∗∗∗ | −0.07∗∗∗ | −0.08∗∗∗ | |||||||

| 7. Edu | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.12∗∗∗ | 0.24∗∗∗ | 0.04∗ | 0.04∗ | −0.39∗∗∗ | ||||||

| 8. MS | 0.76 | 0.43 | −0.05∗∗ | −0.10∗∗∗ | −0.15∗∗∗ | −0.06∗∗∗ | −0.07∗∗∗ | 0.43∗∗∗ | −0.29∗∗∗ | |||||

| 9. Rural | 0.60 | 0.49 | −0.03 | −0.05∗ | −0.08∗∗∗ | 0.02 | 0.04∗ | 0.03 | −0.34∗∗∗ | 0.08∗∗∗ | ||||

| 10. TP | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.10∗∗∗ | 0.09∗∗∗ | −0.04∗ | −0.04∗ | −0.21∗∗∗ | 0.16∗∗∗ | 0.09∗∗∗ | 0.07∗∗∗ | |||

| 11. SES | 2.37 | 0.92 | −0.07∗∗∗ | −0.08∗∗∗ | −0.03 | 0.12∗∗∗ | −0.07∗∗∗ | 0.05∗∗ | 0.06∗∗ | 0.06∗∗ | −0.07∗∗∗ | −0.01 | ||

| 12. Victim | 0.029 | 0.17 | 0.08∗∗∗ | 0.07∗∗∗ | −0.03 | −0.06∗∗ | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.07∗∗∗ | |

| 13. INU | 0.764 | 0.43 | 0.04∗ | 0.11∗∗∗ | 0.17∗∗∗ | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.47∗∗∗ | 0.36∗∗∗ | −0.15∗∗∗ | −0.17∗∗∗ | 0.16∗∗∗ | −0.02 | −0.01 |

- Note: N = 3340. SAX = social acceptance of ex-prisoners; Edu = educational level; INU = Internet use.

- Abbreviations: FOC = fear of crime, MS = marital status, PSC = perception of social conflict, PSE = perceptions of social equity, SES = socioeconomic status, TP = transient population.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

4.2. Common Method Bias Test

In this study, we tested the possible risk of common method bias, using Harman’s single-factor test [76, 78]. The results show that five factors can be extracted using exploratory factor analysis, among which, the factor with the largest explanation rate can only explain 28.424% of the total variance, which is far lower than the standard expert-recommended 40% [78, 79], indicating that our data do not suffer from serious common method bias issues.

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

Before conducting the mediation effect analysis, we examined whether FOC had a direct impact on SAX. The data show that people’s FOC significantly and negatively affects their social acceptance levels (B = −0.10, p < 0.001); the 95% confidence interval (CI) obtained by bootstrap sampling calculation [−0.155, −0.045] does not include zero, indicating that subject to controlling for other conditions, when people experience higher FOC, they tend to have low SAX, which supports Hypothesis 1.

As FOC directly and significantly affects SAX, we explored whether social conflict perception mediates the impact of FOC on SAX. Table 2 shows that FOC has a significant positive impact on the mediating variable of social conflict perception, B = 0.255, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.210, 0.299]. Social conflict perception has a significant negative impact on SAX, B = −0.150, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.187, −0.111]. In addition, the indirect impact of FOC on SAX through social conflict is significant at 95% CI [−0.056, −0.026]; CI does not contain zero, indicating that social conflict perception mediates the association between FOC and SAX. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

| Variables | B | SE | p | Bootstrapped 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Mediator variable model: PSC | |||||

| FOC | 0.255 | 0.023 | < 0.001 | 0.210 | 0.299 |

| Sex | −0.037 | 0.020 | 0.073 | −0.077 | 0.003 |

| Age | −0.004 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | −0.005 | −0.002 |

| Edu | 0.070 | 0.024 | 0.003 | 0.023 | 0.116 |

| MS | −0.035 | 0.026 | 0.177 | −0.086 | 0.015 |

| Rural | −0.014 | 0.022 | 0.523 | −0.056 | 0.028 |

| TP | 0.077 | 0.022 | < 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.121 |

| SES | −0.040 | 0.012 | 0.001 | −0.063 | −0.017 |

| Victim | 0.166 | 0.064 | 0.010 | 0.041 | 0.295 |

| INU | 0.034 | 0.030 | 0.266 | −0.026 | 0.093 |

| Outcome variable model: ACC | |||||

| FOC | −0.046 | 0.022 | 0.034 | −0.089 | −0.004 |

| PSC | −0.150 | 0.019 | < 0.001 | −0.187 | −0.111 |

| Sex | 0.016 | 0.020 | 0.422 | −0.023 | 0.055 |

| Age | −0.007 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | −0.008 | −0.005 |

| Edu | 0.195 | 0.023 | < 0.001 | 0.150 | 0.240 |

| MS | −0.062 | 0.027 | 0.021 | −0.115 | −0.008 |

| Rural | −0.018 | 0.021 | 0.390 | −0.059 | 0.022 |

| TP | 0.048 | 0.021 | 0.020 | 0.008 | 0.088 |

| SES | −0.026 | 0.011 | 0.022 | −0.049 | −0.004 |

| Victim | −0.052 | 0.061 | 0.398 | −0.172 | 0.067 |

| INU | 0.049 | 0.030 | 0.102 | −0.010 | 0.107 |

| FOC ⟶ PSC ⟶ SAX | −0.038 | 0.006 | < 0.001 | −0.051 | −0.027 |

- Note: N = 3340. SAX = social acceptance of ex-prisoners; Edu = educational level; INU = Internet use; FOC ⟶ PSC ⟶ SAX = FOC effect on SAX through PSC.

- Abbreviations: FOC = fear of crime, MS = marital status, PSC = perception of social conflict, SES = socioeconomic status, TP = transient population.

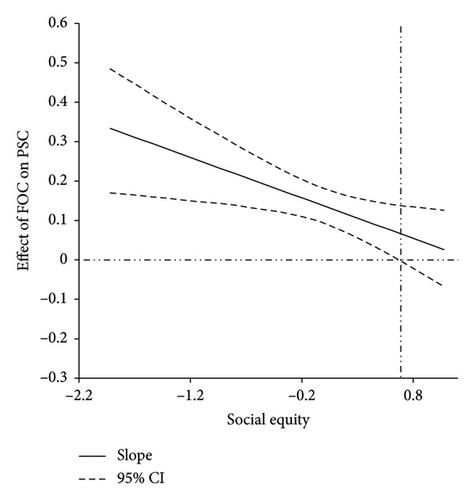

Using a simple mediation model, we explored whether social equality moderates the effect of FOC on social conflict perception. Table 3 shows the results. The cross-product term of FOC and social equality significantly impacts social conflict perception, B = −0.103, p = 0.011, 95% CI [−0.178, −0.020], indicating that social equality moderates the inner relationship between FOC and people’s perceptions of social conflict. We conducted simple slope analyses [80] and drew a J-N diagram (Figure 2) to clearly demonstrate how social equality moderates the relationship between FOC and people’s perceptions of social conflict. When the value of social equality is the mean plus one standard deviation, FOC significantly impacts social conflict perception, B = 0.082, p = 0.009, 95% CI [0.022, 0.144]. Additionally, even when the value of social equality is the mean minus one standard deviation, FOC significantly impacts social conflict perception, B = 0.192, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.128, 0.252]. We then constructed an index to represent social equality, taking the mean plus one standard deviation above and below to check the difference of the effect of FOC on social conflict perception. We found that the 95% CI of this indicator [−0.191, −0.022] does not include zero, indicating that significant differences exist in the effect of FOC on social conflict perception under the two conditions. This finding implies that social equality moderates the effect of FOC on social conflict perception. When social equality is high, FOC has a smaller effect on social conflict perception; however, when it is low, FOC has a larger effect on social conflict perception. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported.

| Variables | B | SE | p | Bootstrapped 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Mediator variable model: PSC | |||||

| FOC | 0.137 | 0.023 | < 0.001 | 0.093 | 0.181 |

| PSE | −0.340 | 0.023 | < 0.001 | −0.385 | −0.293 |

| FOC ∗ PSE | −0.103 | 0.040 | 0.011 | −0.178 | −0.020 |

| Sex | −0.052 | 0.019 | 0.007 | −0.090 | −0.014 |

| Age | −0.005 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | −0.007 | −0.003 |

| Edu | 0.073 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.028 | 0.117 |

| MS | −0.060 | 0.025 | 0.015 | −0.110 | −0.012 |

| Rural | −0.013 | 0.021 | 0.523 | −0.055 | 0.026 |

| TP | 0.060 | 0.021 | 0.003 | 0.020 | 0.101 |

| SES | −0.019 | 0.012 | 0.102 | −0.042 | 0.004 |

| Victim | 0.133 | 0.062 | 0.032 | 0.014 | 0.261 |

| INU | 0.007 | 0.029 | 0.808 | −0.049 | 0.065 |

| Outcome variable model: SAX | |||||

| FOC | −0.032 | 0.023 | 0.154 | −0.077 | 0.012 |

| PSE | 0.049 | 0.023 | 0.035 | 0.003 | 0.096 |

| PSC | −0.137 | 0.020 | < 0.001 | −0.176 | −0.098 |

| Sex | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.347 | −0.020 | 0.058 |

| Age | −0.006 | 0.001 | < 0.001 | −0.008 | −0.005 |

| Edu | 0.194 | 0.023 | < 0.001 | 0.149 | 0.239 |

| MS | −0.058 | 0.027 | 0.031 | −0.112 | −0.005 |

| Rural | −0.018 | 0.021 | 0.379 | −0.059 | 0.022 |

| TP | 0.050 | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.090 |

| SES | −0.029 | 0.011 | 0.012 | −0.052 | −0.007 |

| Victim | −0.050 | 0.061 | 0.415 | −0.169 | 0.068 |

| INU | 0.053 | 0.030 | 0.077 | −0.006 | 0.111 |

- Note: N = 3340. SAX = social acceptance of ex-prisoners; Edu = educational level; INU = Internet use; FOC ⟶ PSC ⟶ SAX = FOC effect on SAX through PSC.

- Abbreviations: FOC = fear of crime, MS = marital status, PSC = perception of social conflict, PSE = perception of social equity, SES = socioeconomic status, TP = transient population.

As social equality moderates the effect of FOC on social conflict perception, we analyzed whether social equality moderates the mediating effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception [64, 81]. We assessed whether the mediating effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception was significant when the level of social equality was high (i.e., mean plus one standard deviation) and low (i.e., mean minus one standard deviation). We also checked whether the 95% CI for the difference between the mediating effects was zero. The results show that when the level of social equality is one standard deviation above the mean, the mediating effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception is significant, B = −0.013, p = −0.019, 95% CI [−0.025, −0.004]. Similarly, when the level of social equality is one standard deviation below the mean, the mediating effect of FOC on social acceptance through social conflict perception is also significant, B = −0.030, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.046, −0.017]. We performed 10,000 bootstrap procedures, determining the 95% CI of the difference in the mediating effects of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception in the two situations = [0.004, 0.034], which did not include zero. The above results show that social equality can not only moderate the effect of FOC on social conflict perception but also the mediating effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception. This implies that the effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict is greater when the level of social equality is lower, supporting Hypothesis 4.

In summary, we focused on four core variables in the hypothesis models, among which SAX is a dependent variable, FOC is an independent variable, and social conflict perception is a mediating variable; that is, FOC affects the SAX through social conflict perception. Social equality is a moderating variable, and its main role is to weaken the association between FOC and social conflict perception. We found a significant negative correlation between FOC and the SAX from the correlation coefficient between the variables, while respondents with higher FOC are less willing to accept ex-prisoners, which is consistent with our hypothesis. There is a significant positive correlation between FOC and social conflict perception, which is also consistent with our hypothesis. Social conflict perception is significantly negatively correlated with SAX, which is also consistent with the hypotheses of this study.

4.4. Robustness Check

Following expert recommendations [82, 83], we analyzed whether the main findings of this study remain unchanged without controlling for variables. In the direct model of FOC affecting SAX without control variables, FOC still significantly and negatively impacts SAX, B = −0.099, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.154, −0.044]. In the simple mediation effect model, in which FOC affects SAX through social conflict perception, the effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception remains significant, B = −0.036, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.052, −0.021]. In the moderated mediation model, without controlling for variables, the cross-product term of FOC and social equality is significant, B = −0.085, p = 0.033, 95% CI [−0.161, −0.004]; when social equality is high (mean plus one standard deviation), the FOC significantly affects social conflict perception, B = 0.121, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.061, 0.183], and when it is low (mean minus one standard deviation), the FOC continues to significantly impact social conflict perception, B = 0.212, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.149, 0.271]. We constructed an index to examine the differences in the effects of FOC on social conflict perception when social equality is high and low. Bootstrapping 10,000 times revealed that the 95% CI of this indicator = [−0.172, −0.005] did not include zero, indicating that social equality moderates the association between FOC and social conflict perception. Regarding whether social equality moderates the effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception, we found that that when social equality is high (mean plus one standard deviation), FOC significantly affects SAX through social conflict perception, B = −0.015, p = 0.003, 95% CI [−0.028, −0.007], and even when low (mean minus one standard deviation), FOC significantly affects social conflict perception, B = −0.027, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.043, −0.014]. We constructed an indicator to represent the difference in the effect of FOC on social conflict perception when social equality is high and low. Bootstrapping 10,000 times revealed that the indicator 95% CI [0.001, 0.026] excludes zero, indicating that social equality moderates the effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception. These results are consistent with previous results, including those of the moderator variables, indicating that the results of this study are robust [82, 83].

5. Discussion

The significance of the results of this study attests to its theoretical contributions, revealing that FOC weakens people’s SAX and that FOC has a strong negative impact on ex-prisoners and may affect the social inclusion of this group of people. Different from the previous research outcomes focused on the impact of FOC on ex-prisoners’ health [84], behavioral habits [85], academic performance [86], work performance [87], lifestyle [88, 89], and the attitude of ex-prisoners toward punishment [90–92], this study indicates that the impact of FOC on social relations remains significant to human development and harmony in society, which deserves additional attention from academics and policymakers. Using representative national data from China, this study highlights social acceptance issues regarding ex-prisoners and their impact on social integration, social harmony, social cohesion, and family solidarity across generations. Although in the past half century crime rates in European welfare states have been showing a downward trend, the overall global FOC level has not shown a significant decline [31, 32].

Previous research has proposed that people with high FOC tend to support harsher punishment being assigned to perpetrators of crime, although the research outcomes feature significant racial differences [5, 92]. People with high FOC usually present avoidance behaviors, psychologically or physically, toward ex-prisoners [15, 16]. Consequently, this study presents the urgency and necessity for governments and nongovernment organizations to support ex-prisoners and help them find acceptance in society. Researchers have argued that people with high FOC tend to support severe punishment of perpetrators and demonstrate overall avoidance behavior, while ex-prisoners are most likely to be marked as “unsafe” and are the least likely to be accepted by such people. Hence, this study proposes that it is necessary to reduce people’s FOC as much as possible based on the presented impact factors, particularly when people have opportunities to interact with ex-prisoners by, for example, living in the same community or being part of the same social network. The study recommends that policymakers should try to reduce people’s FOC by improving the physical environment of the community and increasing the cohesion of its people. In addition, policymakers should try their best to help ex-prisoners substantially so that they avoid recidivistic tendencies owing to a lack of social support.

Moreover, this study explores a possible pathway through which FOC affects SAX through social conflict perception. A mediation effect analysis based on bootstrapping results showed that FOC may cause people to experience a higher level of social conflict perception, making them less willing to accept ex-prisoners. This adds to the literature in terms of understanding how far people’s FOC impacts their SAX, as well as their acceptance of other social groups, which responds to prior literature covering psychological methods of manipulating social acceptance and social exclusion (e.g., [27, 28, 30]).

Further, this study sheds light on people’s perceptions toward social equality, such that if people think that there is social equality, they tend to believe that members of society will be treated equally, regardless of age, race, social status, and so on. In such cases, the impact of FOC on social conflict perceptions and the mediating effect of FOC on SAX through social conflict perception will be smaller. In contrast, if people believe that they might be treated unequally, then FOC will have a greater impact on their social conflict perception. Compared with prior literature, the outcomes of this study provide an innovative research perspective, focusing on the social conditions (social equality) under which FOC affects SAX through social conflict perception. This study underscores that social equality is important for the equal access of ex-prisoners to social networks. Only in a purely equal society can social groups contribute equally to the overall society and benefit equally from their membership within that society, enhancing their health and quality of life. For ex-prisoners, this is especially significant because relatively equal access to social networks may reduce their chances of returning to a life of crime.

Lastly, this study emphasizes the practical implications to society, focusing on how the results can inform policy, practice, and future research. Governments, nongovernmental organizations, and other organizations could contribute to reducing residents’ social conflict perceptions by supporting public activities and encouraging public communication through, for example, organized dancing (referred to as “Guangchang Wu” in Chinese) or mutual care service for residents within the same communities. Enhancing mutual-support care service in the community might also contribute to improving social conflict perceptions and help them develop a better understanding of their social, economic, and political systems. Further, future research could continue to focus on the extent to which FOC impacts different groups of people, and explore whether using modern technology can help residents reduce FOC or social conflict perceptions toward certain social groups.

6. Conclusion

This study aimed to explore the extent to which (1) FOC impacts SAX by elevating social conflict perception and (2) social equality moderates the association between FOC and social conflict perception. The sample comprised 3340 participants, and data were derived from the 2021 CSS conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The bootstrap results indicate that FOC significantly and positively impacts ex-prisoners’ social conflict perception. Our findings indicate that social conflict perception essentially mediates the association between FOC and SAX. The results imply that people who experience higher levels of FOC are more reluctant to accept ex-prisoners. This effect is based partly on social conflict perception as a mediating variable. In particular, when the social equality level is low, the mediating effect becomes more prominent. Our study highlights that people with different impacts of FOC have different understandings of social conflict perceptions, which can be used in social acceptance engagements.

Similar to other studies, our study has certain limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, as the data were cross-sectional, the results cannot provide direct evidence of causal relationships. Future research must make use of data that can provide a clearer understanding of the role of social conflict perception in the relationship between FOC and SAX. Second, there is scope to improve the measurement indicators used in this study. Owing to problems with the design of the CSS data, which constitute secondary data, this study assessed overall perceptions to measure FOC. Future research should consider using measurements based on crime type to measure FOC in depth [17]. Future research must also include more social groups comprising people experiencing homelessness, people with AIDS, and immigrants as target groups. Third, although we examined only one mechanism, that is, FOC affecting people’s SAX, we believe that there could be multiple underlying mechanisms that need to be examined in future studies. Fourth, besides social equality, which was found to moderate the impact of FOC on social conflict perception in this study, future studies should explore other moderators to deepen current understanding. Fifth, this study used data obtained from representative Chinese people. Owing to cultural differences, the results must be interpreted with caution when being generalized to other countries. Future studies must include additional cultural context indicators. Sixth, it is significant to consider timeframes in collecting responses from residents in interviews as much as possible to better measure FOC in future research.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Normal University in China (approval no. AHNU-ET2022073) and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles regarding human experimentation in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent

All participants provided informed consent prior to their participation in the study and were able to discontinue participation at any time for any reason.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: C.X., J.X., and L.M.; funding acquisition: L.M.; formal analysis: C.X., J.X. and L.M.; methodology: C.X. and J.X.; writing – review & editing: C.X. and J.X.; data curation: C.X. and J.X.; project administration: J.X. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article presents part of the interim results of the National Social Science Fund Youth Project “Research on the Change of Huizhou Rural Women’s Marriage and Family, Life Status (1949–2016)” (Grant No. 18CZS062). This work was financially supported by the School of Marxism, Anhui Normal University, through Peak Discipline Research Project (Grant no.: 2023GFXK032).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the student assistants who took part in our research. We thank for the Chinese Social Survey for the data.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in the current study, the Chinese Social Survey, is available at http://css.cssn.cn/css_sy.